Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a ubiquitous human herpesvirus, normally causes an asymptomatic latent infection with very low levels of circulating virus in the peripheral blood of infected individuals. However, EBV does have pathogenic potential and has been linked to several diseases, including posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD), which involves very high circulating viral loads. As a consequence of immunosuppression associated with transplantation, children in particular are at risk for PTLD. Even in the absence of symptoms of PTLD, very high viral loads are often observed in these patients. EBV-infected B cells in the circulations of 16 asymptomatic pediatric solid-organ transplant recipients from Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh were simultaneously characterized for their surface immunoglobulin (sIg) isotypes and EBV genome copy numbers. Patients were characterized as having high and low viral loads on the basis of their stable levels of circulating virus. Patients with high viral loads had both high- and low-copy-number cells. Cells with a high numbers of viral episomes (>20/cell) were predominantly Ig null, and cells with low numbers of episomes were predominantly sIgM positive. Patients with low viral loads carried the vast majority of their viral load in low-copy-number cells, which were predominantly IgM positive. The very rare high-copy-number cells detected in carriers with low viral loads were also predominantly Ig-null cells. This suggests that two distinct types of B-lineage cells contribute to the viral load in transplant recipients, with cells bearing high genome copy numbers having an aberrant Ig-null cellular phenotype.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a member of the family Gammaherpesviridae. Its genes are encoded in a 172-kb double-stranded DNA molecule, and like other gammaherpesviruses, it has a very narrow host range and produces persistent infections in the lymphoid cells of the host. EBV has a tropism for human B cells. The virus is primarily spread via intimate contact; but it is also transmissible by bone marrow engraftment, blood transfusion, or along with a donor organ during solid-organ transplantation. Because of the efficient transmission of the virus via person-to-person contact, more than 90% of the world's population is infected with EBV by adulthood (25).

Despite the high prevalence of EBV infection, EBV causes overt disease only very rarely. Most primary infections occur in childhood and are asymptomatic or the patient exhibits only minor clinical symptoms. In adolescence and adulthood, primary EBV infection can manifest as infectious mononucleosis (11). In an immunocompetent host, a primary infection with EBV is readily resolved by cytotoxic T-cell-mediated immunity, but the host remains asymptomatically infected with the virus for life. The virus has pathogenic potential in certain settings; and associated disease states include oral hairy leukoplakia, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, EBV-associated Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma, and lymphoproliferative disease in immunocompromised patients. EBV-associated posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) in solid-organ transplant recipients is a particular concern. Following organ transplantation, patients typically undergo an immunosuppressive drug regimen to prevent rejection of the donor organ. As a result of this immunosuppression, the immune responses that control EBV-driven B-cell proliferation are reduced. Patients with PTLD can have various clinical presentations, ranging from posttransplant infectious mononucleosis to malignancies containing chromosomal abnormalities (22), and the effects can range from localized lesions to disseminated involvement of the whole lymphoid system (24). General risk factors for the development of PTLD include a primary EBV infection posttransplantation, a cytomegalovirus status mismatch of the donor and the recipient, cytomegalovirus disease, the type and intensity of immunosuppression (22), and the type of solid organ transplanted (19).

EBV-driven PTLD is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the solid-organ transplant recipient, especially in pediatric patients. Estimates of the incidence of disease range from 0.7% (19) to 32% (7) in various allograft recipients, depending on a number of factors. From a large number of separate studies, it has been shown that the diagnosis of PTLD is also associated with a very high EBV load in the peripheral blood (>1,000 copies/105 peripheral blood mononuclear cells [PBMCs]) (5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 15, 17, 18, 23, 26, 29, 31, 32, 35). While healthy immunocompetent adults harbor an average of approximately 0.01 to 0.1 genomes per 105 PBMCs (29), PTLD patients typically have viral loads several orders of magnitude greater at the time of diagnosis. Before the symptoms of PTLD appear, there is a period of 2 to 6 weeks during which the EBV load in the peripheral blood is readily detected and rising. This increase is usually detected by quantitative PCR. Upon resolution of their symptomatic PTLD, patients often retain a much higher (by 2 to 3 orders of magnitude) circulating persistent viral load than a normal latently infected individual. In addition, persistently high viral loads have been observed in a substantial percentage of pediatric solid-organ transplant recipients who have never had a diagnosis of PTLD. This persistently elevated load has generally been attributed to the immunosuppressive drug regimen that is administered to prevent rejection of the transplanted organ (36). Serial monitoring by quantitative PCR reveals that many of these patients harbor persistently elevated viral loads asymptomatically for months to years (10, 15, 28, 33, 37, 38; unpublished observations). The potential complications arising from a very high viral load without overt disease have never been elucidated.

The chronic carrier states exhibited by the immunosuppressed pediatric solid-organ transplant recipient population offer a unique opportunity to study viral latency and risk factors for the development of PTLD. Previously, it has been shown that the latent EBV load is carried in the resting memory B cell (CD19+, immunoglobulin D [IgD] negative, Ki67−, CD23−, CD80−) compartment in the peripheral blood in both immunosuppressed and immunocompetent individuals (1, 2, 21, 30). Further studies have pinpointed latency to the CD27+, CD5− B2 memory type of B cell in the peripheral blood of immunocompetent individuals (33). In immunosuppressed individuals the chronic viral load is carried in the memory-B-cell compartment of the peripheral blood (2, 27). A preliminary analysis of EBV-infected peripheral blood B cells for EBV DNA by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) found that the distribution of the viral genomes in infected cells was related to the patient's viral load (28). In patients with low viral loads, cells had just one or two genomes per nucleus, while in patients with high viral loads, a large portion of the load was carried in cells harboring as many as 20 to 50 genomes per cell (Fig. 1). Increases in load were accompanied by an increase in the number of these high-copy-number cells. Since high-copy-number cells (greater than 10 genomes/cell) were found predominantly in patients with high viral loads, these cells were a distinctive marker for this group of patients. In terms of pathogenic processes, the high-genome-copy-number cells likely arise in a manner different from that for the low-genome-copy-number cells. High-copy-number cells warrant further analysis because they may be a key to understanding the development of at least some PTLDs. Recent evidence suggests that the existence of aberrant cell types may be a main constituent in PTLDs and Hodgkin's disease lymphomas (14, 16, 34). The characterization of the Ig phenotypes of EBV-infected cells in asymptomatic carriers with high and low loads reported here lends support to this notion.

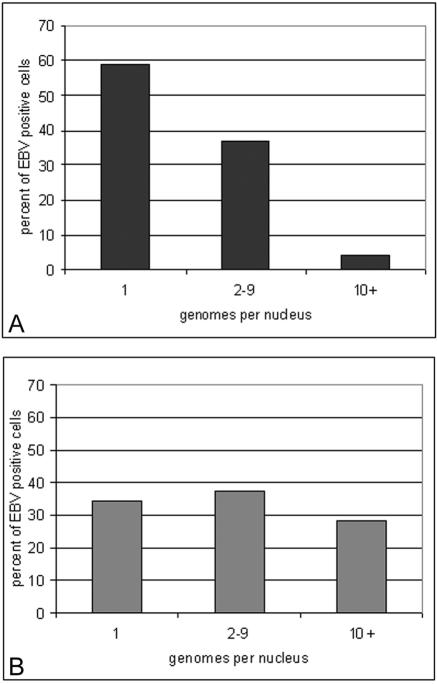

FIG. 1.

EBV genome distribution per infected cell in patients with low (A) and high (B) viral loads. The EBV copy number in infected peripheral blood B cells is expressed as a percentage of all EBV-positive cells present, as determined by FISH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

Since 1995, the EBV loads of transplant recipients attending Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center have been regularly monitored by a quantitative-competitive PCR (QC-PCR) protocol developed in the Department of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh (10). We have monitored bowel, liver, lung, renal, and heart transplant recipients for EBV DNA copy numbers in peripheral blood lymphocytes. We have focused on the pediatric transplant population because we have multiple prospectively collected specimens from more than 190 patients in this group. Only 34.2% of these patients have never had a detectable viral load. A chronic “low” viral load (defined as detectable virus, but with <200 genome copies/105 lymphocytes for >2 months) has been detected in 36.3% of the patients who have been monitored, and a chronic “high” load (defined as >200 genome copies/105 lymphocytes for >2 months) has been detected in 18.4% of the patients. The remaining 11.1% of patients have had viral loads that have fluctuated. As the lower limit of the QC-PCR test is 8 genome copies per 105 lymphocytes (29), normal latent infections are not detected by this assay; thus, the loads detected must be at least 2 to 3 orders of magnitude greater than those associated with normal latency. This research has complied with all relevant federal guidelines and is covered by Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh Human Rights Committee research protocol 00-155.

QC-PCR for EBV loads.

Lymphocytes were prepared from whole-blood samples by centrifugation onto a Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) cushion. The cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and counted. The cell pellets were stored at −20°C until they were ready for PCR. A volume of plasma from each patient equivalent to 4 × 105 cells was ultracentrifuged in an Eppendorf (Westbury, N.Y.) 5417c centrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 90 min in order to pellet cell-free virus. To make lymphocyte and plasma lysates, 20 μl of PCR lysis buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1% Tween 20, 100 μg of proteinase K per ml) was added for every 105 lymphocytes or plasma volume equivalents. The lysates were incubated at 55°C for 1 h, boiled for 10 min to inactivate the proteinase K, and chilled on ice. Primers specific for the PCR target sequence in the EBV genome were designed with OLIGO software (National Biosciences Inc., Plymouth, Minn.). Primers TP1Q5′ (AGGAACGTGAATCTAATGAAGA) and TP1Q3′ (GAGTCATCCCGTGGAGAGTA) amplify a 177-bp EBV sequence (exon 1) in the lmp2a gene. A competitor target was made by deleting 42 bp from a 177-bp EBV amplicon derived from the viral lmp2a exon 1 sequence. For each sample, four tubes containing 8, 40, 200, and 1,000 copies of the viral LMP2a competitor sequence, respectively, along with lymphocyte or plasma lysates equivalent to 105 cells, were subjected to 30 cycles of amplification (94°C for 1 min, 54°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min). Each PCR mixture (50 μl) contained 20 pmol of 5′ and 3′ primers, 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris (pH 9.0), 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.25 mM deoxynucleotides (Pfizer, New York, N.Y.). One unit of Amplitaq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, Mass.) was used in each reaction mixture. The PCR products were analyzed on 3% agarose gels containing 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA electrophoresis buffer and 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide per ml.

The QC-PCR assay for EBV is used to quantitate viral loads over a range of 8 to 5,000 copies of viral DNA in 105 lymphocytes. Normal latent infection (0.01 to 0.1 copies/105 lymphocytes) is not detected by this protocol, and detectable levels of viral DNA reflect a viral genome burden at least 2 to 3 orders of magnitude above those associated with normal latency.

Cell sorting with magnetic beads.

Lymphocytes were positively sorted for CD19+ B cells by using MACS CD19 Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, Calif.). Histopaque lymphocyte preparations from patient blood samples were mixed with 20 μl of CD19 Microbeads per 107 total cells, and the mixture was incubated for 15 min at 4°C. The cells were washed and magnetically separated by using a positive-selection LS column. The CD19+ cells that were retained were eluted with magnetic activated cell sorting buffer and spun onto Superfrost Plus glass slides (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, N.H.) with a Shandon Cytospin 3 apparatus (Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, Mass.) at 500 rpm for 5 min. Namalwa cells, a Burkitt's lymphoma cell line that contains two integrated copies of the EBV genome, were also spun onto the same slide for use as a control in the in situ hybridization reaction. The purities of the CD19+ populations in a control sample of PBMCs ranged from 90 to 95%, as confirmed by flow cytometry.

Construction of DNA probe.

A probe specific for EBV double-stranded DNA was made from plasmid p1040, which contains a cloned BamHI WWYH fragment of EBV strain B95-8. The 14.7-kb fragment was cloned into a holding vector and linearized with HindIII. The cut DNA was purified from the agarose gel with a MinElute gel extraction kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.), and probes of 250 to 300 bp specific for EBV double-stranded DNA were generated with the Prime-A-Gene labeling system (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and labeled with digoxigenin-11 (DIG)-2′-dUTP (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) at room temperature overnight. To terminate the reaction, the mixture was heated to 95°C for 2 min, followed by chilling in an ice bath. EDTA (20 mM) was added, followed by a standard phenol-chloroform extraction of the probe. The purified probe was stored at −20°C until direct use in the in situ hybridization reaction.

In situ hybridization.

FISH was performed with CD19+ cells from patient peripheral blood samples. The slides were fixed in methanol-acetic acid (3:1) at room temperature for 15 min. After the slides were washed twice with 1× PBS, the slides were aged in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) at 37°C for 30 min, followed by dehydration in an increasing ethanol series. The slides were prewarmed and denatured in a 70% formamide-2× SSC solution for 2 min and immediately placed in a cold graded series of ethanol for 5 min each. For each sample, 50 ng of probe, 5 μg of salmon sperm DNA, and 20 μg of yeast tRNA were suspended in a solution of 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, and 1× SSC. This hybridization mixture was heated to 80°C for 10 min, followed by preannealing at 37°C for 15 min. After the slides were prewarmed at 37°C, 30 μl of the hybridization mixture was added to each sample for incubation at 37°C overnight. On the following day, the slides were washed in a 50% formamide-2× SSC solution for 30 min at 37°C, followed by a 30-min wash in 2× SSC at 37°C. The slides were treated with RNase H (8 U of RNase H/ml in RNase H reaction buffer) for 1 h, also at 37°C. The slides were then washed twice with 2× SSC.

Immunofluorescence (IF).

Surface Ig (sIg) expression was detected with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against sIgM, sIgA, and sIgG (Biosource International, Camarillo, Calif.). The blocked slides were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with the respective antibody at a 1:250 dilution. They were then washed twice with 1× PBS. A cell was scored as either positive or negative on the basis of the level of expression of sIg.

Immunological detection of EBV-specific probe.

To detect the bound DIG-labeled EBV-specific probe, the blocked slides were incubated with anti-DIG-rhodamine-Fab fragments (Roche) for 30 min at room temperature. The slides were washed twice with 1× PBS, dried, mounted with Vectashield mounting medium plus 4′,6′-diamidono-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and sealed. A positive signal is characterized by a red dot, with a surface area of approximately 22 pixels in the DAPI-stained nucleus (blue). Each specific signal represents one EBV genome, although some genomes may be closely spatially related and are visualized as one larger signal.

Photomicroscopy.

The sealed slides were examined under a Nikon E600 microscope equipped with a SPOTII charge-coupled device digital camera. Images of the cells were generated and analyzed with Metamorph software (Universal Imaging, Westchester, Pa.).

RESULTS

Surface isotype expression in CD19+ cells.

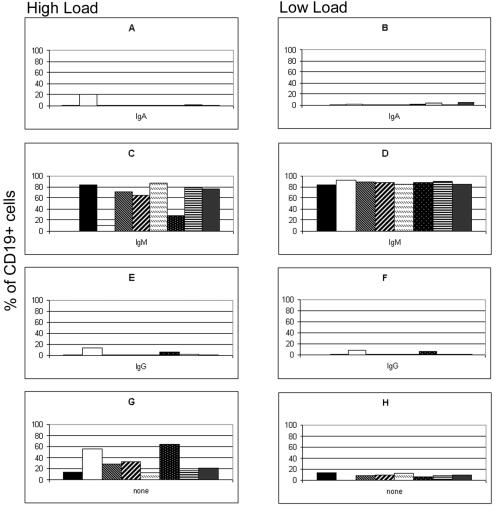

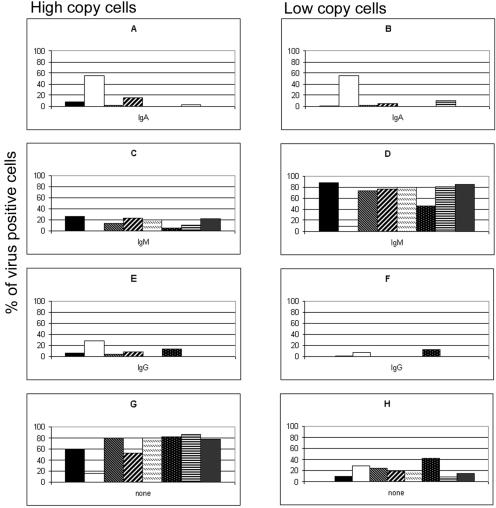

IF for the detection of surface expression of the IgM, IgA, and IgG isotypes was conducted with CD19+ cells that had been positively sorted from the PBMCs of children who had undergone solid-organ transplantation at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh. Eight patients with high viral loads and eight patients with low viral loads (as defined in the Materials and Methods) were selected for this study (Table 1). The EBV genome distributions in patients with low and high viral loads are shown in Fig. 1. Detection of surface expression of IgD was not performed, since we and others have previously shown by PCR that persistent infection with EBV does not involve the naïve IgD-positive (IgD+) B cells of both healthy and immunosuppressed individuals (1, 2, 12, 20, 27). Cells positive for IgM, IgA, and IgG were observed in all patient samples (Fig. 2). Similar numbers of IgG-expressing cells were observed in both the patients with high viral loads and the patients with low viral loads (3.4 and 2.6%, respectively). There were slightly more IgA+ cells in the patients with high viral loads (3.6% in patients with high viral loads and 2.1% in patients with low viral loads), although this average was skewed by the unusually high percentage (20%) of IgA+ virus-infected cells in one patient with a high viral load (patient 2). When the data for patient 2 are removed, the percentage of IgA+ cells in patients with high viral loads is comparable to the percentage of IgA+ cells in patients with low viral loads. The patients with low viral loads had substantially more IgM+ cells than the patients with high viral loads (87.2 and 62.3%, respectively), while the patients with high viral loads had substantially more cells with no detectable Ig isotype than the patients with low viral loads (30.8 and 9.0%, respectively). While some of the Ig-null cells observed may be attributed to the sorting procedure, which leaves a small percentage (5 to 10%) of CD19− cells in the enriched population, it cannot account for the differences in the populations of comparably enriched CD19+ populations detected.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patient populations with high and low viral loads

| Patient group and patient no. | Sexa | History of PTLD | Age (mo) at transplant | Time posttransplant (mo) of specimen retrieval | EBV status pretransplantb | Type of transplant | EBV load (no. of copies/10 PBLs)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High viral load | |||||||

| 1 | F | No | 10 | 12 | Neg | Liver | 5,000 |

| 2 | M | No | 15 | 25 | Neg | Liver | 2,500 |

| 3 | F | Yes | 8 | 16 | Neg | Liver | 2,500 |

| 4 | F | Yes | 19 | 21 | Neg | Heart | 2,000 |

| 5 | M | No | 44 | 21 | Neg | Liver | 500 |

| 6 | F | No | 6 | 56 | Neg | Heart | 500 |

| 7 | M | Yes | 120 | 80 | Neg | Kidney | 200 |

| 8 | F | No | 125 | 6 | Neg | Double Lung | 200 |

| Low viral load | |||||||

| 1 | F | Yes | 72 | 70 | Neg | Liver | 100 |

| 2 | M | No | 152 | 3 | Neg | Kidney | 100 |

| 3 | F | No | 22 | 41 | Neg | Liver | 80 |

| 4 | M | Yes | 61 | 67 | Neg | Liver | 40 |

| 5 | M | No | 2 | 37 | Pos | Liver | 20 |

| 6 | M | No | 118 | 86 | Unknown | Kidney | 20 |

| 7 | M | Yes | 83 | 156 | Unknown | Multi-visceral | 8 |

| 8 | M | No | 100 | 28 | Pos | Kidney | 8 |

F, female; M, male.

Neg, negative; Pos, positive.

PBLs, peripheral blood lymphocytes.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of isotypes on CD19+ cells from patients with high and low viral loads. The proportions of sIgA+ (A and B), sIgM+ (C and D), and sIgG+ (E and F) peripheral blood B cells in patients with chronic high loads (A, C, E, and G) and patients with chronic low loads (B, D, F, and H) were determined by FISH and IF and are expressed as the percentages of all CD19+ cells present. (G and H) The percentage of cells in which no sIg was detected. Each graph shows the results for eight patients with high viral loads (A, C, E, and G) and eight patients with low viral loads (B, D, F, and H).

Surface isotype expression of virus-infected cells in patients with low viral loads.

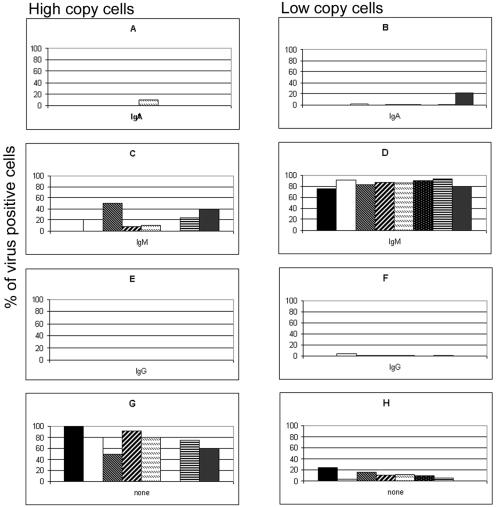

Examples of cells expressing each isotype are shown in Fig. 3. A combined FISH-IF procedure was used to generate an isotype profile for the EBV-infected cells in purified CD19+ cells from eight patients with low viral loads (Fig. 4). Typically, patients with low viral loads carry 1 to 2 viral genomes per infected B cell in the peripheral blood. Cells with a greater number of EBV genome copies are rare or undetectable. The majority (85.5%) of the low-copy-number cells from this patient group were IgM+. Low-copy-number cells expressing IgA and IgG were also detected at a very low frequency (average proportion of IgA+ cells, 3.3%; average proportion of IgG+ cells, 1.0%). For patients with low viral loads, an isotype for 10.3% of low-copy-number virus-infected cells was not identified by our FISH-IF procedure. High-copy-number cells in this patient population are extremely rare. Two patients had no detectable high-copy-number cells, while the remaining six patients had, on average, only 1 or 2 high-copy-number cells among an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 cells per slide. Of these high-copy-number cells, approximately 70% did not have detectable Ig isotype expression. In addition, no IgG+ high-copy-number cells were identified in any of the patients with low viral loads. One patient with a low viral load (patient 5) had a small percentage of IgA+ high-copy-number cells. All other high-copy-number cells detected were IgM+ (Fig. 4).

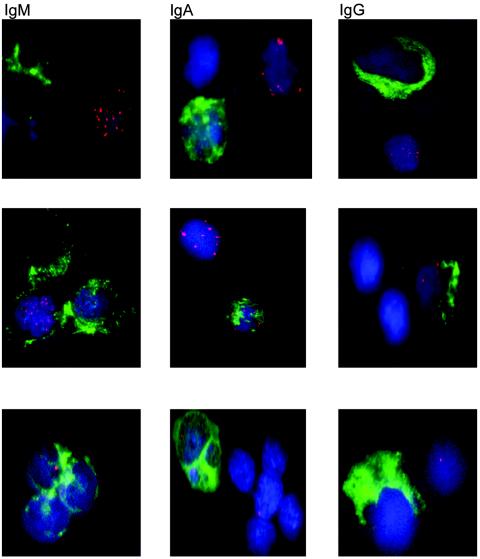

FIG. 3.

EBV genomes and sIg expression. Representative EBV-positive and sIg-positive cells, as detected by FISH and IF, are shown. The top row of photos represents virus-positive high-copy-number cells, without surface expression of Ig, with an IgM+, IgA+, and IgG+ cell nearby. The middle row of photos shows double-positive high-copy-number cells with multiple copies of the virus and expression of sIgM, sIgA, and sIgG. Virus-positive low-copy-number cells with a single viral genome present are shown in the left two photos on the bottom row (IgM+ and IgA+ cells). The photo at the bottom right shows a low-copy-number cell with no surface Ig expression next to an IgG+ cell. For each photo, red indicates the viral genome, blue indicates the nucleus, and green indicates sIg expression.

FIG. 4.

Distribution of isotypes in virus-infected cells from eight patients with low viral loads. The proportions of EBV-positive, sIgA+ (A and B), sIgM+ (C and D), and sIgG+ (E and F) high-copy-number (A, C, E, and G) and low-copy-number (B, D, F, and H) cells in the peripheral blood B cells of patients with persistent low viral loads were determined by FISH and IF and are expressed as percentages of the high- and low-copy-number cells detected. (G and H) The percentage of infected cells in which no sIg was detected. Each graph shows the results for eight patients with low viral loads.

Surface isotype expression of virus-infected cells in patients with high viral loads.

The FISH-IF procedure was applied to positively sorted CD19+ cells from the peripheral blood of eight patients with high viral loads. Examples of both positive and negative surface Ig isotype expression in virus-infected cells are shown in Fig. 3. Virus-infected cells with low numbers of viral genomes were present in all patients, and these cells were predominately IgM+ (67.2%) (Fig. 5). IgA+ and IgG+ low-copy-number cells were also observed at lower frequencies in some patients with high viral loads (Fig. 5). All patients with high viral loads carried high-copy-number cells (average, 86 high-copy-number cells per slide), and most of these cells (68.0%) had no detectable surface Ig isotype expression. A significant difference (P < 0.05) in the number of high-copy-number cells per slide existed between the patients with high and low viral loads. Up to 85% of the high-copy-number cells from several of the patients with high viral loads showed no sIg expression. Of the high-copy-number cells with detectable sIg expression, 45.7% were IgM+, 31.7% were IgA+, and 22.6% were IgG+.

FIG. 5.

Distribution of isotypes in virus-infected cells from patients with high viral loads. The proportions of EBV-positive, sIgA+ (A and B), sIgM+ (C and D), and sIgG+ (E and F) high-copy-number (A, C, E, and G) and low-copy-number (B, D, F, and H) cells in the peripheral blood B cells from patients with persistent high viral loads were determined by FISH and IF and are expressed as percentages of the high- and low-copy-number cells detected. (G and H) The percentage of infected cells in which no sIg was detected. Each graph shows the results for eight patients with high viral loads.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we have reported that children who undergo solid-organ transplantation often carry persistently elevated EBV loads in their peripheral blood. Upon direct examination of the virus-infected B cells from the peripheral blood by FISH, we determined that in patients with loads of <200 copies/105 lymphocytes, infected cells had 1 to 2 copies of the viral genome per nucleus (low-copy-number cells). Patients with high viral loads (>200 copies/105 lymphocytes) had these low-copy-number cells, but they also had another population of virus-infected cells with 20 to 50 genomes per nucleus (high-copy-number cells) (28). We have now characterized the sIg isotypes for the two types of virus-infected cells from a larger pediatric transplant population.

In our study we used fluorescent probes to directly visualize the infected cells and simultaneously determine the sIg phenotypes of individual infected cells and the viral genome copy number in individual infected cells. Among the patients in our study, the proportion of peripheral blood B cells with sIgM, sIgG, or sIgA was within the normal range for children. In both patients with low viral loads and patients with high viral loads, the EBV-infected cells with a low genome copy number had mainly IgM B-cell receptors. Previous work has shown that for both immunocompetent and immunosuppressed individuals, the EBV latent load was carried in what appeared to be the resting memory-B-cell compartment (CD19+, IgD negative, Ki67−, CD23−, CD80−) (1, 2, 27). The present study indicates that for the pediatric transplant population, these virus-infected cells carry low numbers of EBV episomes and are IgM+. The implication, therefore, is that they do not appear to have undergone isotype switching after EBV infection. They do not necessarily need to have arisen from a population of cells participating in germinal-center reactions within the lymph nodes.

As in previous studies with pediatric transplant recipients, high-copy-number cells were a distinctive feature of patients carrying high viral loads and were responsible for high circulating loads at the time of PTLD diagnoses (28). Unexpectedly, the characterization of the Ig isotype of the B-cell receptors on these cells revealed that the majority of these cells had no detectable sIg expression. Internal controls demonstrated that this was not a technical problem with the detection of sIg in these experiments. IgM+, IgA+, and IgG+ cells were observed on all slides; and the frequencies of the different isotypes in the circulating B-cell pool was within the expected range. Some cells with high genome copy numbers did express sIg. For these, the frequency with which the virus appeared in B cells of different isotypes was not the same as the frequency of the isotypes in the circulating B-cell population. The IgG isotype was underrepresented and the IgA isotype was overrepresented in the virus-infected subpopulation. The simplest explanation for the origin of high-copy-number null cells would be that after infection of mature naïve B cells, the cells proliferated (increasing the viral genome copy number per cell) and then attempted to make an isotype switch. When an isotype switch was productive, it more often led to IgA expression. It would appear, however, that most of the switching attempts were unsuccessful, leading to the Ig-null cell phenotype.

Because B cells require a functional surface antigen receptor to receive survival signals throughout the lifetime of the cell, Ig-null cells are normally incompatible with survival in vivo. They would be expected to be rapidly eliminated and not permitted to enter or persist in the circulation. The persistence in the peripheral blood of B cells with no detectable Ig expression suggests that these cells may be receiving an abnormal survival signal, most likely provided by EBV. The high-copy-number cells are, in this respect, atypical B cells. It is possible that these cells have survived germinal-center reactions which produced unsuccessful Ig affinity maturation and/or isotype switching. Ig-null cells have recently been described in EBV-infected B cells in patients with angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia (4), EBV-positive Hodgkin's disease (14, 16), and EBV-positive PTLD (3, 34). A lack of CD20 and sIg light-chain expression was also observed in various PTLD lesions by flow cytometry (13). The latter studies have led researchers to suggest that EBV interferes with the normal B-cell differentiation and selection processes in patients with PTLD (3). The Ig-null phenotype of high-copy-number EBV-infected B cells in asymptomatic children with solid-organ transplants suggests that such interference is not confined to the disease state and that patients with high viral loads, in particular, show signs of aberrant B-cell development and may be at risk for further EBV-driven complications.

Acknowledgments

We thank Camille Rose for assistance with the FISH technique and Holly Betts and Corin Jenkins for dedicated technical support.

This work was supported in part by NIH grant HL074732 (to D.R.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Babcock, G., L. Decker, M. Volk, and D. Thorley-Lawson. 1998. EBV persistence in memory B cells in vivo. Immunity 9:395-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babcock, G., L. Decker, R. Freeman, and D. Thorley-Lawson. 1999. Epstein-Barr virus-infected resting memory B cells, not proliferating lymphoblasts, accumulate in the peripheral blood of immunosuppressed patients. J. Exp. Med. 190:567-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brauninger, A., T. Spleker, A. Mottok, A. Baur, R. Kuppers, and M. L. Hansmann. 2003. EBV-positive lymphoproliferations in post-transplant patients show immunoglobulin V gene mutation patterns suggesting interference of EBV with normal B cell differentiation processes. Eur. J. Immunol. 33:1593-1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brauninger, A., T. Spieker, K. Willenbrock, P. Gaulard, H. Wacker, K. Rajewsky, M.-L. Hansmann, and R. Kuppers. 2001. Survival and clonal expansion of mutating “forbidden” (immunoglobulin receptor-deficient) Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells in angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. J. Exp. Med. 194:927-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buteau, C., and C. Paya. 2001. Clinical usefulness of Epstein-Barr viral load in solid organ transplantation. Liver Transplant. 7:157-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decker, L., L. Klaman, and D. Thorley-Lawson. 1996. Detection of the latent form of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in the peripheral blood of healthy individuals. J. Virol. 70:3286-3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finn, I., J. Reyes, J. Bueno, and E. Yunis. 1998. Epstein-Barr virus infections in children after transplantation of the small intestine. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 22:299-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green, M., J. Reyes, S. Webber, M. Michaels, and D. Rowe. 1999. The role of viral load in the diagnosis, management, and possible prevention of Epstein-Barr virus associated posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease following solid organ transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 4:292-296. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green, M., M. Michaels, S. Webber, D. Rowe, and J. Reyes. 1999. The management of Epstein-Barr virus associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders in pediatric solid organ transplant recipients. Pediatr. Transplant. 3:271-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green, M., T. Cacciarelli, G. Mazariegos, L. Sigurdsson, L. Qu, D. Rowe, and J. Reyes. 1998. Serial measurement of Epstein-Barr viral load in peripheral blood in pediatric liver transplant recipients during treatment for posttransplant lymphoproliferative diseases. Transplantation 66:1614-1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hicks, M. J., J. Jones, L. Minnich, K. Weigle, A. C. Thies, and J. Layton. 1983. Age-related changes in T- and B-lymphocyte subpopulations in the peripheral blood. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 107:518-523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph, A., G. Babcock, and D. Thorley-Lawson. 2000. EBV persistence involves strict selection of latently infected B cells. J. Immunol. 165:2975-2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaleem, Z., A. Hassan, M. Pathan, and G. White. 2004. Flow cytometric evaluation of posttransplant B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 128:181-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanzler, H., R. Kuppers, M. Hansmann, and K. Rajewsky. 1996. Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells in Hodgkin's disease represent the outgrowth of a dominant tumor clone derived from (crippled) germinal center B cells. J. Exp. Med. 184:1495-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kogan, D., M. Burroughs, S. Emre, T. Fishbein, A. Moscona, C. Ramson, and B. Shneider. 1999. Prospective longitudinal analysis of quantitative Epstein-Barr virus polymerase chain reaction in pediatric transplant recipients. Transplantation 67:1068-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuppers, R., K. Rajewsky, M. Zhao, et al. 1994. Hodgkin disease: Hodgkin and Reed-Sterberg cells picked from histological sections show clonal immunoglobulin gene rearrangements and appear to be derived from B cells at various stages of development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10962-10966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limaye, A., H. Meei-Li, E. Atienza, J. Ferrenberg, and L. Corey. 1999. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in sera from transplant recipients with lymphoproliferative disorders. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1113-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucas, K., R. Burtin, S. Zimmerman, J. Wang, K. Cornetta, K. Robertson, C. Lee, and D. Emanuel. 1998. Semi-quantitative Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) polymerase chain reaction for the determination of patients at risk for EBV-induced lymphoproliferative disease after stem cell transplantation. Blood 91:3654-3661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mihalov, M. I., P. Gattusa, K. Abraham, E. Holmes, and V. Reddy. 1996. Incidence of post-transplant malignancy among 674 solid-organ transplant recipients at a single center. Clin. Transplant. 10:248-255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyashita, E., B. Yang, G. Babcock, and D. Thorley-Lawson. 1997. Identification of the site of Epstein-Barr virus persistence in vivo as a resting B cell. J. Virol. 71:4882-4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyashita, E., B. Yang, K. Lam, D. Crawford, and D. Thorley-Lawson. 1995. A novel form of Epstein-Barr virus latency in normal B cells in vivo. Cell 80:593-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nalesnik, M., R. Jaffe, T. Starzl, A. Demetris, K. Porter, J. Burnham, L. Makonka, M. Ho, and J. Locker. 1988. The pathology of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders occurring in the setting of cyclosporine A-prednisone immunosuppression. Am. J. Pathol. 133:173-192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohga, S., E. Kubo, A. Nomura, N. Suga, E. Ishii, A. Suminoe, T. Inamitsu, A. Matsuzaki, N. Kasuga, and T. Hara. 2001. Quantitative monitoring of circulating Epstein-Barr virus DNA for predicting the development of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease. Int. J. Hematol. 73:323-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paya, C. V., J. J. Fung, M. A. Nalesnik, E. Kieff, M. Green, G. Gores, T. M. Habermann, R. H. Wiesner, L. J. Swinnen, E. S. Woodle, and J. S. Bromberg. 1999. Epstein-Barr virus-induced posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Transplantation 68:1517-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rickinson, A. B., and E. Kieff. 1996. Epstein-Barr virus, p. 2397. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Kneip, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Virology, vol. 2. Raven Press, New York, N.Y.

- 26.Riddler, S., M. Breining, and J. McKnight. 1994. Increased levels of circulating Epstein-Barr virus-infected lymphocytes and decreased EBV nuclear antigen antibody responses are associated with the development of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease in solid organ transplant recipients. Blood 84:1972-1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose, C., M. Green, S. Webber, D. Ellis, J. Reyes, and D. Rowe. 2001. Pediatric solid-organ transplant patients carry chronic loads of Epstein-Barr virus exclusively in the immunoglobulin D-negative B-cell compartment. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1407-1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rose, C., M. Green, S. Webber, L. Kingsley, R. Day, S. Watkins, J. Reyes, and D. Rowe. 2001. Detection of EBV genomes in peripheral blood B cells from solid-organ transplant recipients by fluorescent in situ hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2533-2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowe, D., L. Qu, J. Reyes, N. Jabbour, E. Yunis, P. Putnam, S. Todo, and M. Green. 1997. Use of quantitative competitive PCR to measure Epstein-Barr virus genome load in the peripheral load of pediatric transplant patients with lymphoproliferative disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1612-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowe, M., G. Niedobittek, and C. Young. 1998. EBV gene expression in posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 20:389-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Servi, J., E. Stevens, E. Verchuuren, I. Pronk, W. van der Bij, M. Harmsen, T. The, C. Meijer, A. van der Brule, and J. Middledorp. 2001. Frequent monitoring of Epstein-Barr virus DNA load in unfractionated whole blood is essential for the early detection of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease in high risk patients. Blood 97:1165-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shapiro, R., M. Nalesnik, J. McCauley, S. Fedorek, M. Jordan, V. Scantlebury, A. Jain, C. Vivas, D. Ellis, S. Lombardozzi-Lane, P. Randhawa, J. Johnston, T. Hakala, R. Simmons, J. Fung, and T. Starzl. 1999. Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders in adult and pediatric renal patients receiving tacrolimus-based immunosuppression. Transplantation 68:1851-1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thorley-Lawson, D., and G. Babcock. 1999. A model for persistent infection with Epstein-Barr virus: the stealth virus of human B cells. Life Sci. 65:1433-1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Timms, J., A. Bell, J. Flavell, P. Murray, A. Rickinson, A. Traverse-Glehen, F. Berger, and H.-J. Delecluse. 2003. Target cells of Epstein-Barr-virus (EBV)-positive post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease: similarities to EBV-positive Hodgkin's lymphoma. Lancet 361:217-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vajro, P., S. Lucariello, S. Migliarello, B. Gridelli, A. Vegnent, R. Iorio, F. Smets, I. Quinto, and G. Scala. 2000. Predictive value of Epstein-Barr virus genome copy number and BZLF1 expression in blood lymphocytes of transplant recipients at risk for lymphoproliferative disease. J. Infect. Dis. 181:2050-2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webber, S., and M. Green. 2000. Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders: advances in diagnosis, prevention, and management in children. Prog. Pediatr. Cardiol. 11:145-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang, J., Q. Tao., I. Flinn, P. Murray, L. Post, H. Ma, S. Piantadosi, M. Caligiuri, and R. Ambinder. 2000. Characterization of Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells in patients with posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disease: disappearance after rituximab therapy does not predict clinical response. Blood 96:4055-4063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zanghill, S., D. Hsu, M. Kickuk, J. Garvin, C. Stolar, J. Haddad, Jr., S. Stylianos, R. Michler, A. Chadburn, D. Knowles, and L. Addonizio. 1998. Incidence and outcome of primary Epstein-Barr virus infection and lymphoproliferative disease in pediatric heart transplant recipients. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 17:1161-1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]