Abstract

Background

Advance care planning (ACP) is recommended for all persons to ensure that the care they receive aligns with their values and preferences.

Objective

Evaluate an ACP intervention developed to better meet the needs and priorities of persons with chronic diseases, including mild cognitive impairment.

Research Design

A year-long, pre-post intervention employing lay community health workers (care coordinator assistants [CCAs]) trained to conduct and document ACP conversations with patients during home health visits with pre/post evaluation.

Subjects

The 818 patients were 74.2 years old (mean); 78% women; 51% African American; 43% Caucasian.

Measures

Documentation of ACP conversation in EHR fields and health care utilization outcomes.

Results

In this target population ACP documentation rose from 3.4% (pre-CCA training) to 47.9% (post) of patients who had at least one discussion about ACP in the EHR. In the one-year pre-intervention period, there were no differences in admissions, emergency department (ED) visits, and outpatient visits between patients who did and did not have ACP discussion. After adjusting for prior hospitalization and ED use histories, ACP discussions were associated with a 34% less probability of hospitalization (HR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.45–0.97), and similar effects are apparent on ED use independent of age and prior ED use effects.

Conclusions

Patients with chronic diseases including mild cognitive impairment can engage in ACP conversations with trusted home health care providers. Having ACP conversation is associated with significant reduction in seeking urgent health care and in hospitalizations.

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) is important for persons to ensure the care they receive is aligned with their values and preferences. There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates patients want to participate in discussions and decisions about their care,1–5 yet studies show that providers frequently fail to invite patients to explore options for care. 6–14 Thus many persons’ values and needs go undocumented and preferences for care remain unknown.6,7,15 The recent Institute of Medicine report Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life16 calls for strategies to enhance participation in ACP and to develop ACP models that are thorough, conducted over time, and focused on preparation for “in-the-moment” decision making rather than identification of exact treatment preferences.

A new collaborative care model designed to address the needs of elderly individuals includes health system workforce members such as community health workers (CHW) trained to implement new ACP with older adult patients. These new workforce members, called Care Coordinator Assistants (CCA) in our collaborative care team at the Indiana University Center for Aging Research (IUCAR)’s Aging Brain Care (ABC) Program, work in interdisciplinary teams and provide care to patients and caregivers at home. The CCAs were hired as part of a collaborative care model17 that had been developed and tested in controlled trials 18–23 demonstrating improved care for elderly individuals with multiple co-morbidities, including varying degrees of cognitive impairment due to depression and/or dementia. CCAs serve as a critical link between patients and caregivers, primary care and specialist providers, the palliative care team, social workers and relevant community resources. (see table, Supplemental Digital Content 1 for a description of the IUCAR’s ABC program).

The collaborative care team members recognized many barriers to ACP.24 Advance care planning is particularly important for patients who may lose their ability to make decisions for themselves, and has been demonstrated to improve end of life experiences for patients with dementia.25 However, providers, trained to cure disease, are often reluctant to discuss death and dying16 or have inadequate training in communicating about difficult subjects such as ACP.26 Health systems may also lack a clear protocol regarding who should initiate ACP and in what setting27 and may lack structural support for planning, such as electronic repositories for documentation, or support to allow providers time to explore patient values and preferences.16 Patients and families may feel uncomfortable bringing up the topics of advanced disease and death during rushed clinical encounters. Early on the team members realized that CCA were capable and well-positioned to initiate conversations about goals of care, life priorities, and other topics related to ACP with patients and families. Thus, in 2014, twenty CCAs, received training in ACP and were provided with an electronic health record decision support tool to prepare them to implement planning with their older adult patients.21

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the CCA ACP intervention by analyzing pre- and post-documentation of ACP in the CCA patients’ electronic health record.

Methods

Study Design

This study was both a mixed-methods and pre-post observational analysis of the ABC study including the interactions between CCAs, their patients, and their patients’ caregivers. The target population for the intervention were all 818 patients enrolled in the ABC program during the one-year study (July 1, 2014 to June 30, 2015). In the ABC program, every Medicare beneficiary aged 65 or older with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) code of depression or dementia, who had at least one visit within the past 2-years to a primary care practice, were enrolled. Approximately 80% of the CCAs’ patients have a diagnosis of depression and 22% have a diagnosis of dementia as determined by CCAs during an initial assessment, using the Mini-Mental Status Examinations and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The median number of patients seen per CCA during the study period was 90 (range: 83–103).

Intervention

CCA ACP Interactions with Patients and the Health Care Team

CCA ACP training consisted of 4 workshops, 2 simulation sessions, support from an electronic health record (EHR) clinical decision support tool, and monthly case conferences (see table, Supplemental Digital Content 1 for a description of CCA’s Roles and Training).

Following their training, CCAs demonstrated they were able to develop a close relationship with their patients and their patients’ caregivers during repeat home visits over many months. Home visits allowed time to explore patient’s preferences across multiple visits, enabling patients and/or family members time for reflection and conversation between visits. CCA ACP was supervised and supported by the ABC collaborative care team, including RNs, social workers, and medical director, as well as the palliative care team.

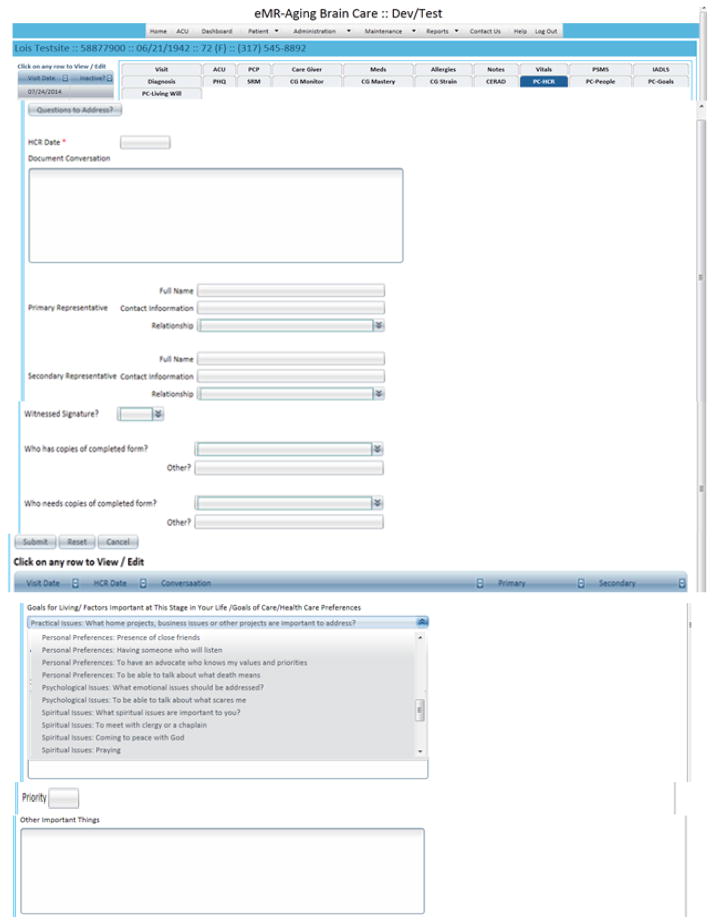

CCA Advance Care Planning Electronic Health Record Decision Support Tool

The CCAs and project ACP experts worked with electronic health system programmers to expand existing ACP fields and test an ACP clinical decision support (CDS) tool. The clinical decision support tool includes prompts for gathering and documenting biopsychosocial-spiritual histories, goals for living and care preferences, healthcare representative (HCR), power of attorney, Living Will, and POST forms (see Table 1. Advance Care Planning Data Fields in Aging Brain Center’s Electronic Health Record for a list of the ACP data fields). CCA helped with prioritizing and documenting goals of living, identifying and documenting a HCR, and explaining, answering questions, and making appropriate referrals for completion of other ACP documents.

Table 1.

Advance Care Planning Data Fields in Aging Brain Center’s Electronic Health Record

| Goals for Living: What is important to you? (with sample items) | ACP forms |

|---|---|

| Achieving a sense of completion | Health Care Representative form |

| To feel that my life is complete | Primary-Name/Contact information/relationship, or person(s) being considered |

| To say good bye to important people in my life | Back-up/Secondary-Name/Contact information |

| Attending to spiritual/religious concerns | Health Care Power of Attorney |

| To be at peace with God | Name/Contact information/relationship or person(s) being considered |

| To meet with clergy or a chaplain | Witnessed signature (Y or N; if no, who would you like to witness?) |

| Dealing with symptoms and personal care | Notarized (Y or N; if no, do you need assistance getting notarized?) |

| To have human touch | Durable Power of Attorney for Financial Affairs |

| To be free from pain | Name/Contact information/relationship or person(s) being considered |

| Having a positive patient provider relationship | Notarized (Y or N; if no, do you need assistance getting notarized?) |

| To trust my doctor | Living Will |

| To have a nurse I feel comfortable with | Witnessed signature (Y or N; if no, who would you like to witness?) |

| Maintaining personal wholeness | Feeding Tube |

| Not dying alone | Witnessed signature (Y or N; if no, who would you like to witness?) |

| To have someone who will listen to me | POST |

| Making personal and treatment preferences known | Name of doctor you (patient or HCR) would want to sign the form (who will review, modify, and sign document as warranted) |

| Not being connected to machines | Witnessed signature (Y or N; if no, who would you like to witness |

| To die at home | |

| Preparing for the end of life | The following must be included for all forms: |

| To have my funeral arrangements made | Document of conversation |

| Not being a burden to my family | Questions to address/ by whom (CCA, RN, SW, MD, other) |

Following their training, CCAs began documenting patient preferences in the ACP EHR fields (see Figure 1. Screen Shots of the Electronic Health Record Advance Care Planning Clinical Decision Support Fields for screen shots of ACP EHR fields). The EHR was designed to create a letter describing patient preferences from information entered into the EHR that patients could give to their healthcare substitute decision-maker.

Figure 1.

Screen Shots of the Electronic Health Record Advanced Care Planning Clinical Decision Support Fields

Legend: PC=Palliative Care; HCR=Health Care Representative

CCA Ongoing Case Conferences

Weekly case conferences provided CCAs and palliative care providers the opportunity to discuss cases and explore the best ways to translate the ACP education into action with patients, families and caregivers. The ACP training team also met with the CCAs monthly to review ACP information being documented in the EHR, discuss difficult cases, and stimulate peer coaching. Field notes were collected by facilitator-trainers (DL, WG) to capture the CCAs’ successes, challenges, and reactions to promoting ACP discussions.

Evaluation of the Intervention

Qualitative: Post-Intervention Patient Interviews

In-person semi-structured interviews with patients were conducted to solicit patient perspectives on the acceptability and relevance of the services, especially those focused on advanced care directives. Interviews were conducted between August and October, 2015 with a convenience sample of patients who had been served by CCAs. The purpose of these interviews was to explore patient experiences with the CCA, with particular emphasis on the discussions patients may have had with CCAs that were focused on ACP and designation of HCRs. These interviews were between 15–40 minutes in duration (mean interview time was 32 minutes). Interviews were conducted by one research assistant (KW) who used a semi-structured interview guide (see Appendix 1). Extensive field notes were taken during and immediately following the interviews. Interviews were audiotaped and used to augment the field notes. All but one interview took place in the patients’ homes.

Quantitative

Main Outcome Measures: The main outcome was to determine if the intervention increased the number of ACP discussions. ACP discussions were captured in the ABC EHR. The secondary outcome measures were the Emergency Department (ED) and inpatient utilization rates in the year subsequent to the intervention. All utilization measures (ED, Inpatient, and Outpatient visits) and comorbidities were captured from Indiana’s Health Information Exchange. Demographics (age, race, gender), ACP discussion types, and CCA visit type were obtained from the ABC EHR.

Data Analysis

Qualitative Analyses

Qualitative data from the interviews were analyzed by two study investigators (TI, KW) experienced in thematic analysis and crystallization immersion methods.28 Investigators independently reviewed field notes to identify initial themes then worked together to build consensus on major themes. They then independently coded field notes through an iterative process using thematic content analysis.29 As new codes were identified, the coding scheme was refined using the constant comparative method.30 Investigators met regularly to compare and discuss codes and come to consensus on discordantly coded data. Saturation was achieved after no new themes emerged from the data. We capped the interview sample size at 15, because reviewer-analysts (TI, KW) agreed that saturation of content had been reached at that number. Codes within and across field notes were compared and synthesized into overarching themes.

Quantitative Analyses

We used Chi-Square tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests to compare demographics and comorbidities between the 392 patients with and the 426 patients without an ACP discussion during the study period. We used a mixed effects logistic regression model to test whether the intervention increased the occurrence of ACP discussions. This model included a random effect for patient and a fixed effect for the time period. We used proportional hazards models to examine the association of ACP discussion with time to inpatient admission or time to ED visit while adjusting for demographics, comorbidities, and prior utilization over a one-year period following their first visit with a CCA. Follow-up time for censored observations was calculated as the time from first visit to last documented utilization encounter. All observations with follow-up times greater than 1 year were censored at 1 year. For these models, an ACP discussion was included as a time dependent variable. As a time dependent variable, ACP discussion was marked as absent for time from first visit to discussion date and then marked as present from discussion date until the end of the stay. To model the association of ACP discussions on the number of hospitalizations and ED visits while adjusting for other variables, we ran Poisson regression models with the log (follow-up time) included as an offset variable. Outcomes reported looked at only new ACP discussions that occurred after July 1, 2014. Several sensitivity analyses documented the robustness of the results to including or excluding from analyses patients who had prior ACP discussions noted at baseline.

Results

Study participants

The average age of the 818 patients enrolled in the study was 74.2 years old and the majority were women (78%). The patient population was 51% African American and 43% Caucasian. The most common co-morbidities included depression (80.1%), diabetes (60.5%), coronary artery disease (45.1%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (38.5%), stroke (33.6%), congestive heart failure (32.8%), cancer (32.0%), dementia (22.4%), and arthritis (8.7%). Of those with dementia and a documented mini-mental status exam (MMSE), 9.0% had severe dementia, 28.2% had moderate dementia, and 62.8% had mild dementia using standard MMSE criteria. The majority of enrolled patients were capable of making independent decisions.

The average number of home visits for each patient was 3.4 and the mean number of other contacts outside the home including phone contacts, clinic visits, and contact during inpatient stays was 8.6 over the study period. Contacts ranged from brief phone contacts to 15–90 minute home visits. Of the 2,746 home visits, 2,382 (86.7%) were conducted by the CCA, 225 (8.2%) were done by a social worker, and 139 (5.1%) were conducted by a nurse.

Which Patients had Advanced Care Planning Discussions?

CCAs documented ACP discussions with 392 of 818 eligible patients. CCAs were trained to address the needs raised by their patients and caregivers. If a patient or caregiver had acute medical or psychosocial concerns, these issues were the focus of the visit, in part explaining why only 48% had ACP discussions. Table 2. Comparison of Patients With and Without Advance Care Planning Discussions includes study patients’ demographics, co-morbidities, and number of health care contacts and home visits including a comparison of these patient-descriptors for those who did and did not have an ACP discussion documented during the study period.

Table 2.

Comparison of Patients With and Without Advance Care Planning Discussions

| Overall (n=818) | No Discussion (n=426) | Discussion (n=392) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | ||||

| Mean Age (SD) | 74.2 (7.5) | 74.7 (7.7) | 73.6 (7.2) | 0.026 |

| % Female | 78.1 | 75.8 | 80.6 | 0.108 |

|

Race % African-American |

51.2 | 52.4 | 50.0 | 0.780 |

| % Caucasian | 43.2 | 42.4 | 44.1 | |

| % Other | 5.5 | 5.2 | 5.9 | |

| Co-morbidities | ||||

| % Depression | 80.1 | 77.9 | 82.4 | 0.110 |

| % Diabetes | 60.5 | 57.5 | 63.8 | 0.074 |

| % CAD | 45.1 | 45.1 | 45.2 | 0.981 |

| % COPD | 38.5 | 37.1 | 40.0 | 0.389 |

| % Stroke | 33.6 | 35.2 | 31.9 | 0.315 |

| % CHF | 32.8 | 32.6 | 32.9 | 0.932 |

| % Cancer | 32.0 | 33.1 | 30.9 | 0.494 |

| % Dementia | 22.4 | 25.4 | 19.1 | 0.033 |

| % Arthritis | 8.7 | 8.0 | 9.4 | 0.460 |

| % Any Discussion Prior to July 1, 2014 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 0.128 |

| Mean # Home Visits (SD) | 3.4 (3.0) | 2.8 (2.8) | 4.0 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Mean # Other Contacts* (SD) | 8.6 (6.3) | 7.7 (6.2) | 9.6 (6.2) | <0.001 |

other contacts= include phone contacts, clinic visits, and contact during inpatient stays.

Compared with patients who had no ACP conversation documented, patients who had an ACP conversation were slightly younger (73.7 y/o versus 74.7 y/o) and statistically less likely to have a diagnosis of dementia (19.1% versus 25.4%). There was no difference in documented ACP discussion in the two groups during the 12-month period prior to beginning the study. Patients with ACP discussions documented had significantly more home visits (4.0 versus 2.8) and significantly more contacts (9.6 versus 7.7) outside the home.

From July 1, 2013 – June 30, 2014, prior to training the CCAs for advanced care discussions and incorporation of these discussions into their home visits, only 3.4% (29/834) of patients had at least one discussion about their ACP. From July 1, 2014 to June 30, 2015, after CCAs began incorporating these discussions into their visits, 47.9% (392/818) of patients had at least one discussion about their ACP documented in the EHR. CCA’s made > 99% of the entries into the EHR ACP fields with a social worker rarely entering a POST.

What Happened in these ACP Discussions?

The discussions about ACP were recorded in EHR ACP fields. Table 3. Characteristics of Advance Care Planning Discussions shows a break down in the focus of the ACP discussions. Of those 392 patients whose discussion was recorded, 95.9% had discussions about their HCRs and 64% had a HCR form signed, 22.7% of patients had their goals of living recorded, 18.4% had a discussion about a living will, and 7.4% discussed their preferences on artificial nutrition.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Advance Care Planning Discussions

| ACP* Discussion Topics | ACP Discussion (n=392) |

|---|---|

| Discussion about HCR | 95.9 % (n=376) |

| HCR** Signed | 64.0 % (n=251) |

| Goals of Living | 22.7 % (n=89) |

| Living Will | 18.4 % (n=72) |

| Artificial nutrition | 7.4 % (n=29) |

ACP=advance care planning;

HCR =health care representative

Of the 72 patients who had discussions about their living will, 22 patients completed the living will form. Three patients left their form with their family, and 13 patients had already completed their living will. Eleven patients had the discussion only and did not fill out any paperwork, and 23 patients’ living will status is unknown.

Of the 29 patients who had a discussion about artificial nutrition, 20 patients preferred that they not receive artificial nutrition. Six patients decided to leave the decision to their HCR, and one patient stated that he or she wanted all measures to be taken to sustain life. Two patients’ preferences were unknown.

What were the Patients’ Views of CCA ACP Discussions?

All patients recalled meeting with a CCA and discussing ACP issues. All but one patient reported knowing about the completion of a HCR form, though nearly half of patients were not aware of its present location (location unknown 46%, at home 46%, in clinic 8%). A large majority of patients had named either a spouse or another member of their family as the designated HCR. Among 13 patient interviews with information, patients had designated 8 children, 3 spouses, 1 friend, and 1 other as their HCRs. Most patients had shared information from the HCR form with at least one other person in addition to the HCR him/herself, including children (4 instances among 15 interviews), doctors (4 instances), others (3 instances). In five interviews, the patient referenced their HCR as the only person aware of the HCR document content.

The CCA conversations with patients about ACP were described as helpful and important. These conversations stimulated systematic thinking about various issues pertaining to end-of-life care, death, and issues beyond death (e.g., funeral arrangements, and financial arrangements). It was often noted that patients who had a discussion with their CCA about ACP were able to organize their thoughts, write down preferences and talk openly about their wishes without emotional involvement. While interviewees said that having these kinds of ACP conversations with their families was uncomfortable because children or other members of the family simply did not want to talk about these matters with the person they would ultimately lose, the same patients found that conversations with CCAs about end-of-life preferences were certainly challenging but also comfortable.

Was there an Impact of CCA ACP Discussions on Utilization?

In the 1-year period prior to the CCA’s ACP training and documentation of discussions, there was no difference in inpatient admissions (23.0% versus 27.3%; p=0.157) and ED visits (42.0% versus 41.8%; p=0.958) between patients who did and did not have ACP discussion during the intervention period. In the 1-year period following the first CCA visit during the intervention period, patients who had documented ACP conversations were significantly less likely to be admitted to the hospital and go to the ED.

Table 4. Proportional Hazard Results for Time to Inpatient Stay or Any Emergency Department Visit within 1 year of First Care Coordinator Assistant Visit displays the proportional hazard model results of the association of ACP discussions with time to first subsequent ED visit and hospitalization. For inpatient admission, congestive heart failure, stroke and prior inpatient stays were associated with an increased risk of hospitalization. Prior ED visit and dementia are associated with increased risk of an ED visit, while increasing age was associated with decreased ED visits. After adjusting for demographics, comorbidities, prior hospitalization and ED use histories, ACP discussions were associated with a 34% less probability of hospitalization (HR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.45–0.97), and similar effects were apparent for ED use.

Table 4.

Proportional Hazard Results for Time to Inpatient Stay or Any Emergency Department Visit within 1 year of First Care Coordinator Assistant Visit

| Any Inpatient Stay | Any ED Visit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-Value | HR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

| Age | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.428 | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.021 |

| Female | 0.87 (0.63, 1.18) | 0.368 | 1.08 (0.81, 1.42) | 0.608 |

| Any Prior Inpatient Stay | 1.81 (1.34, 2.43) | <0.001 | 1.30 (1.01, 1.69) | 0.045 |

| Any Prior ED* Visit | 1.19 (0.90, 1.58) | 0.228 | 1.98 (1.56, 2.52) | <0.001 |

| Log (Outpatient Visits) | 0.94 (0.79, 1.13) | 0.536 | 0.91 (0.78, 1.06) | 0.213 |

| Diabetes | 1.25 (0.94, 1.68) | 0.131 | 1.04 (0.82, 1.32) | 0.746 |

| CHF | 1.94 (1.46, 2.59) | <0.001 | 1.19 (0.93, 1.53) | 0.162 |

| COPD | 1.17 (0.89. 1.55) | 0.256 | 1.21 (0.96, 1.52) | 0.117 |

| CAD | 1.19 (0.89, 1.60) | 0.237 | 1.04 (0.82, 1.32) | 0.752 |

| Stroke | 1.53 (1.16, 2.01) | 0.002 | 1.14 (0.90, 1.44) | 0.287 |

| Cancer | 1.21 (0.93, 1.59) | 0.158 | 0.84 (0.66, 1.06) | 0.146 |

| Dementia | 1.15 (0.83, 1.58) | 0.402 | 1.34 (1.03, 1.75) | 0.030 |

| Depression | 1.16 (0.80, 1.69) | 0.432 | 0.97 (0.72, 1.32) | 0.866 |

| Discussion | 0.67 (0.46, 0.98) | 0.041 | 0.60 (0.42, 0.84) | 0.003 |

ED =Emergency Department

Similar results were obtained from the Poisson regression models for the number of hospitalizations and ED visits in the subsequent year. Patients with any ACP discussion had reduced risk of hospitalizations (RR=0.78, 95% CI=0.64–0.95; p=0.016) and ED visits (RR=0.73, 95% CI=0.62–0.86; p=0.001).

Discussion

The Institute of Medicine report Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life16 clearly articulates the need for new strategies to promote ACP so the care a person receives aligns with their values and preferences. This is especially important for our aging population plagued with chronic diseases and cognitive impairment who are becoming progressively less able to share their health care preferences and whose likelihood of either having an ACP conversation and documenting these discussions remains low.

This study demonstrates the feasibility of incorporating CHW into healthcare teams as highly effective members capable of helping to close important gaps in ACP. As uncovered during case conferences, CCAs moved from doubt and fear about their ability to have ACP conversations, through various phases of acceptance of this as part of their job description, to demonstrated high levels of competence once armed with the skills and an electronic CDS tool. As seen in Table 3, CCA were highly successful in helping patients identify a HCR and complete the appropriate documentation. CCA were increasingly able to open and “normalize” conversations with patients about their personal “goals of living.” At the last case conference, several CCA expressed gratitude for having received the ACP training and expressed a desire to train others due to their changed perception of the high importance of this work.

An increased number of contacts between CCAs and their patients and visits to patients’ homes were associated with an increase chance of having an ACP discussion. Although an increased number of contacts with traditional health care providers does not predict an increased likelihood of having an ACP conversation, the CCAs were noted by patients to be capable of developing very special and trusting relationships through frequent, “high touch” home visits. It is likely that the less rushed home setting following several relationship- and trust-building visits facilitated having meaningful conversations about end-of-life care.

Patients with mild or moderate cognitive impairment can have ACP conversations. However, with more advanced dementia, we found a significantly diminished association with having an ACP conversation reinforcing the importance of having conversations as early as possible while patients are still cognitively competent.

In other settings an association between clarifying patient’s health care preferences and subsequent health care service utilization has been noted31. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report that similar high-impact outcomes, including decreased hospitalizations and ED visits, can be attained by including well trained community workers competent in engaging and documenting end-of-life preferences.

Our study has several limitations. We report on the outcomes of a clinical program with a pre-post design rather than a randomized trial. Our study population included only one subset of the population of elderly patients (with varying degrees of cognitive impairment and/or depression) from health care systems affiliated with an academic health center, limiting the generalizability of our findings. The care provided by CCAs was comprehensive and the intervention was complex therefore one cannot attribute the increase documentation of ACP discussions or the decreased health utilization to any one aspect of the intervention.

Despite study limitations, our health care system leaders have agreed to hire CCAs to provide comprehensive services to patients with chronic diseases including assisting with ACP based on the documented positive patient health outcomes, decreased health care utilization, and net cost savings.32 Additionally, our statewide Area Agencies on Aging have asked for assistance with ACP training and use of our EHR and CDS tools for use by home health care providers caring for elderly and disabled patients across the state of Indiana. It is also promising that many states use Medicaid waivers to reimburse CHWs33 and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recently announced funding for CHWs who deliver preventive care services.34 We believe that CHWs can and will play an increasing important role in promoting and documenting patients’ advance care plans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Grant Number 1C1CMS331000-01-00 from the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies. The research presented here was conducted by the awardee. Findings might or might not be consistent with or confirmed by the findings of the independent evaluation contractor. This publication was also made possible by the Walther Cancer Foundation Inc., Indianapolis, IN. (0122.01) and the Office of Behavioral and Social Science-National Institute of Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (5R25AR060994).

Funding Source:

The project described was supported by Grant Number 1C1CMS331000-01-00 from the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies. This publication was also made possible by the Walther Cancer Foundation Inc., Indianapolis, IN. (0122.01) and the Office of Behavioral and Social Science-National Institute of Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (5R25AR060994).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure:

No potential conflicts of interest exist for all authors

Ethical Review

Institutional board review (IRB) approval was obtained to conduct this study (KC IRB Protocol #: 1506203948). Consent for study enrollment was not required by the IRB because it qualified as an “exempt” study.

References

- 1.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Preparing for the end of life: preferences of patients, families, physicians, and other care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:727–37. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Final Chapter: Californians’ Attitudes and Experiences with Death and Dying. 2012 at http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/F/PDF%20FinalChapterDeathDying.pdf.

- 3.Tobler D, Greutmann M, Colman JM, Greutmann-Yantiri M, Librach SL, Kovacs AH. Knowledge of and preference for advance care planning by adults with congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:1797–800. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pardon K, Deschepper R, Vander Stichele R, et al. Preferred and actual involvement of advanced lung cancer patients and their families in end-of-life decision making: a multicenter study in 13 hospitals in Flanders, Belgium. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:515–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:315–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright AA, Zhang B, Keating NL, Weeks JC, Prigerson HG. Associations between palliative chemotherapy and adult cancer patients’ end of life care and place of death: prospective cohort study. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2014:348. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anonymous. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. Jama. 1995;274:1591–8. [Erratum appears in JAMA 1996 Apr 24;275(16):1232] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heyland DK, Barwich D, Pichora D, et al. Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:778–87. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO, et al. Physician factors associated with discussions about end-of-life care. Cancer. 2010;116:998–1006. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson JE, Gay EB, Berman AR, Powell CA, Salazar-Schicchi J, Wisnivesky JP. Patients rate physician communication about lung cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:5212–20. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tulsky JA, Fischer GS, Rose MR, Arnold RM. Opening the black box: how do physicians communicate about advance directives? Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:441–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-6-199809150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agledahl KM, Gulbrandsen P, Forde R, Wifstad A. Courteous but not curious: how doctors’ politeness masks their existential neglect. A qualitative study of video-recorded patient consultations. J Med Ethics. 2011;37:650–4. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.041988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. Jama. 2000;284:2476–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston SC, Pfeifer MP, McNutt R. The discussion about advance directives. Patient and physician opinions regarding when and how it should be conducted. End of Life Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1025–30. doi: 10.1001/archinte.155.10.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine (IOM) Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaMantia MA, Alder CA, Callahan CM, et al. The aging brain care medical home: Preliminary data. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2015;63:1209–13. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boustani MA, Sachs GA, Alder CA, et al. Implementing innovative models of dementia care: The Healthy Aging Brain Center. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15:13–22. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.496445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2002;288:2836–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katon WJ, Schoenbaum M, Fan MY, et al. Cost-effectiveness of improving primary care treatment of late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1313–20. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austrom MG, Hartwell C, Moore PS, Boustani M, Hendrie HC, Callahan CM. A care management model for enhancing physician practice for Alzheimer Disease in primary care. Clinical gerontologist. 2006;29:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Tu W, Stump TE, Arling GW. Cost analysis of the Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders care management intervention. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57:1420–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2007;298:2623–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Litzelman DK, Cottingham AH, Griffin W, Inui TS, Ivy SS. Enhancing the prospects for palliative care at the end of life: A statewide educational demonstration project to improve advance care planning. Palliat Support Care. 2016:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1478951516000353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vandervoort A, Houttekier D, Vander Stichele R, van der Steen JT, Van den Block L. Quality of dying in nursing home residents dying with dementia: does advanced care planning matter? A nationwide postmortem study. PloS one. 2014;9:e91130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greutmann M, Tobler D, Colman JM, Greutmann-Yantiri M, Librach SL, Kovacs AH. Facilitators of and barriers to advance care planning in adult congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2013;8:281–8. doi: 10.1111/chd.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gott M, Gardiner C, Small N, et al. Barriers to advance care planning in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Palliat Med. 2009;23:642–8. doi: 10.1177/0269216309106790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research: Methods for primary care. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research: Transaction publishers. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bischoff KE, Sudore R, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Smith AK. Advance Care Planning and the Quality of End-of-Life Care in Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61:209–14. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.French DD, LaMantia MA, Livin LR, Herceg D, Alder CA, Boustani MA. Healthy Aging Brain Center improved care coordination and produced net savings. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:613–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. [Accessed July 2, 2016];State Community Health Workers Model State Reform. at https://www.statereforum.org/state-community-health-worker-models.

- 34.Community Health Worker(s: Roles and Opportunities in Health Care Delivery System Reform. 2016 at Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/community-health-workers-roles-and-opportunities-health-care-delivery-system-reform.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.