Abstract

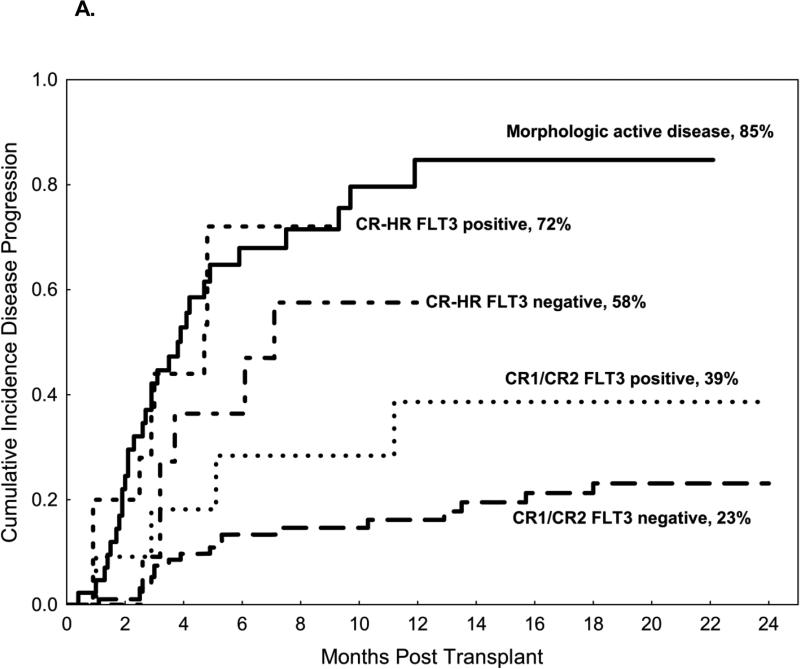

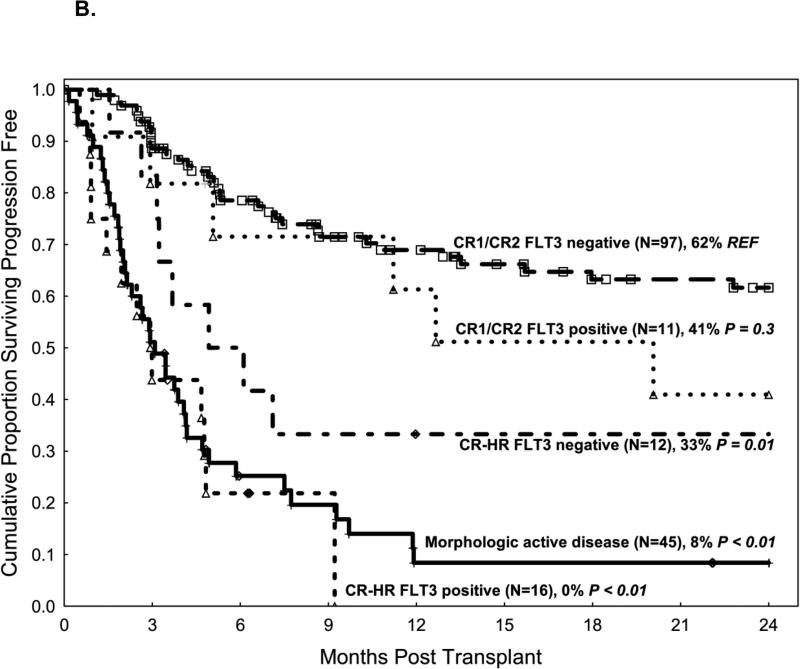

In patients with AML with FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) mutations, the significance of minimal residual disease (MRD) detected by PCR before allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) on outcomes after transplant remains unclear. We identified 200 patients with FLT3-AML who underwent SCT at our institution. Disease status at transplant was: first or second complete remission (CR1/CR2, n=119), high-risk CR (third or subsequent CR, marrow hypoplasia, or incomplete count recovery) (CR-HR, n=31), and morphological evidence of active disease (AD, n=50). The median follow-up was 27 months, and the 2-year overall and progression-free survival were 43% and 41%, respectively. Relapse was highest in the AD group (85%) and the CR-HR FLT3 MRD positive group (72%), followed by CR-HR FLT3 MRD negative (58%), CR1/CR2 FLT3 MRD positive (39%), and lowest in the CR1/CR2 FLT3 MRD negative group (23%). On multivariate analysis, independent factors influencing the risk of relapse were detectable morphological disease and FLT3 MRD by PCR pre-transplant. Factors that did not influence the relapse risk included: age, graft type, graft source, type of FLT3 mutation, or conditioning intensity. Morphologic and molecular remission status at the time of transplant were key predictors of disease relapse and survival in patients with FLT3-AML.

Keywords: FLT3+ acute myeloid leukemia, allogeneic stem cell transplant, minimal residual disease

Introduction

In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), cytogenetic abnormalities strongly influence treatment outcomes. However, the role of molecular abnormalities remains less well understood. Acquired somatic mutations in the FMS-related tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) gene are present in up to 30% of patients with AML with diploid cytogenetics, which makes FLT3 one of the most frequently mutated genes in AML.[1, 2] FLT3 is a tyrosine kinase receptor for the FLT3 ligand. Internal tandem duplication (ITD) of FLT3 or mutations in the activation loop of the tyrosine kinase domain (TKD), predominantly at codon 835 or 836, cause constitutive activation of the tyrosine kinase. This activates downstream signaling of the RAS, MAPK, and STAT5 pathways, leading to dysregulation of cellular proliferation.[3, 4] AML with FLT3 ITD carries a poor prognosis owing to its higher risk of relapse.[2, 5] While the optimal management of patients with FLT3 mutated AML is still controversial, allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) early in the course of the disease has emerged as the preferred therapy owing to a higher risk of relapse in these patients. [6-9] Even after SCT, disease relapse remains a significant cause of treatment failure.[5, 10] Some studies identified the presence of a high ratio of mutant to wild-type FLT3 alleles as a high-risk feature in patients with FLT3 mutated AML.[11] However, in patients with FLT3 mutated AML treated with SCT other potential predictors of a relapse remain incompletely understood.

Minimal residual disease (MRD) detection techniques are emerging as useful tools to risk stratify patients both before and after SCT.[12] Many centers now use multi-color flow cytometry for MRD detection in AML patients. The use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for detection of MRD is still controversial, and most centers do not routinely use PCR for MRD detection.[13, 14] Moreover, the utility of FLT3 detection by PCR as a minimal residual disease marker at the time of SCT and its impact on post-transplant relapse rates is unknown.

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of disease status before transplant on relapse and survival in patients with FLT3 mutated AML treated with SCT. Specifically, we investigated the utility of MRD detection by PCR pre-transplant on the prognosis of these patients.

Methods

Study design and data collection

We retrospectively screened 1,255 AML patients who underwent their first SCT between January 2000 and October 2014 and identified 200 adult patients with FLT3 ITD or FLT3 TKD mutations detected at diagnosis (Table 1). Patients were considered to have FLT3 mutated AML if one of these mutation types was detected, irrespective of the allele burden. FLT3 status before transplant was assessed using bone marrow samples collected within 30 days before the patient received the transplant.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Value (n=200) |

|---|---|

| Male/female | 98/102 |

| Median age (range) | 51 years (18-72 years) |

| >50 years, no. (%) | 106 (53) |

| Karnofsky performance status ≥80%, no. (%) | 128 (64) |

| Hematopoietic cell transplant–comorbidity index score ≥4, no. (%) | 38 (19) |

| Diploid cytogenetic, no. (%) | 119 (60) |

| Disease status at transplant, no. (%) | |

| CR1 | 99 (49) |

| CR2 | 20 (10) |

| CR-HR | 31 (16) |

| Third or subsequent complete remission | 4 |

| PIF/CRi | 10 |

| PIF/hypoplastic marrow | 3 |

| First relapse/CRi | 11 |

| First relapse/hypoplastic marrow | 3 |

| Morphologic evidence of disease | 50 (25) |

| FLT3 detected at the time of transplant (excluding patients with disease on morphologic analysis), no. (%) | 27/150 (18) |

| CR1/CR2 | 11 |

| CR-HR | 16 |

| Donor source, no. (%) | |

| Matched sibling | 62 (31) |

| 1 antigen mismatched sibling | 1 (1) |

| 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated | 86 (43) |

| 8/8 HLA-matched unrelated | 9 (4) |

| 9/10 HLA-matched unrelated | 11 (5) |

| Cord blood | 18 (9) |

| Haploidentical | 13 (7) |

| Stem cell source, no. (%) | |

| Peripheral blood | 110 (55) |

| Bone marrow | 72 (36) |

| Cord blood | 18 (9) |

| FLT3 mutation type, no. (%) | |

| FLT3 ITD | 160 (80) |

| FLT3 TKD mutation (835/836) | 26 (13) |

| Both FLT3 ITD and FLT3 TKD mutation (835) | 8 (4) |

| Unknown | 6 (3) |

| Conditioning regimen, no. (%) | |

| Myeloablative | 170 (85%) |

| Busulfan based | 148 |

| Reduced intensity | 30 (15%) |

| Melphalan based | 25 |

CR1: first complete remission; CR2: second complete remission; CRi: complete remission with incomplete blood count recovery; PIF: primary induction failure; ITD: internal tandem duplication; TKD: tyrosine kinase domain; HLA: human leukocyte antigen

FLT3 mutation detection

A multiplex fluorescence-based PCR analysis for ITD and kinase domain (D835, D836) mutations in FLT3 was performed on DNA isolated from bone marrow aspirate samples as previously described.[15] Briefly, fluorescently labeled PCR primers were used to amplify targeted juxtamembrane domain and kinase domain sequences. PCR product sizes were determined using capillary gel electrophoresis on a 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The presence of PCR fragments larger than the wild-type allele indicated ITD. To detect TKD D835/D836 mutation, PCR products were digested with the EcoRV restriction enzyme before capillary electrophoresis. Wild-type alleles cut by this enzyme yield two fragments, whereas alleles with mutations at D835/D836, which alter the EcoRV recognition site, yield one fragment. The analytical sensitivity of these assays is approximately 1% mutant alleles in a background of wild-type alleles.

Definitions and endpoints

The main objective was to study the impact of MRD detected by PCR (done on marrow samples within 30 days preceding the SCT) on risk of relapse post-transplant in patients with FLT3 mutated AML. The primary endpoint was to determine the effect of FLT3 PCR detected prior to transplant on relapse incidence appreciated by the 2-year cumulative incidence of relapse. The secondary endpoints were the 2-year non-relapse mortality (NRM), overall survival, and progression-free survival (PFS). On morphologic examination, presence of disease was defined as more than 5% blasts in the bone marrow.

Outcomes were compared between subgroups according to their morphologic disease status (in complete remission or with disease present) and FLT3 status by PCR (molecular MRD positive or MRD negative) before transplant. Patients in complete remission were classified as being in first complete remission (CR1), second complete remission (CR2), or high-risk remission (CR-HR). CR-HR included third or subsequent complete remission (CR3) as well as complete remission with incomplete count recovery (CRi) or marrow hypoplasia after primary induction failure (PIF) or after first relapse. We analyzed patients in the CR-HR group separately given that they have a higher risk of relapse than patients in the CR1 or CR2. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Statistical methods

Time to event was assessed from the day of stem cell infusion. Overall survival and PFS were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. For overall survival, death from any cause was considered an event, while for PFS, death or disease relapse was considered an event. The risk of relapse was estimated using the cumulative incidence method, with death in the absence of disease considered a competing risk.[16] Risk factors for disease progression and PFS were assessed on univariate and multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Statistical significance was defined at the 0.05 level. Analyses were performed using Stata 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 51 years (range 18-72 years). Eighty-five percent of patients received myeloablative conditioning (n=170). At the time of transplant, by morphologic examination, 49% of patients (n=99) were in CR1, 10% (n=20) were in CR2, 16% (n=31) were in CR-HR, and 25% had morphologic detectable disease (more than 5% bone marrow blasts) (AD; n=50). Patients with high-risk morphological remission (N=31, 16%) included: CR3 or subsequent CR (n=4), CRi or marrow hypoplasia after PIF (n=13), and CRi or marrow hypoplasia after 1st relapse (n= 14). Of the 150 patients in CR1, CR2, or CR-HR, 27 patients had detectable FLT3 by PCR (CR1 or CR2, n=11; CR-HR, n=16). Eighty-four percent of patients had FLT3 ITD, while 17% of patients had FLT3 TKD mutations.

Impact of FLT3 by PCR on relapse

Figure 1A compares relapse incidence between morphologic and molecular subgroups. The 2-year cumulative incidence of leukemia relapse was 45% in all patients. The cumulative incidence of relapse was highest for patients with morphological disease present at the time of transplant (85%) and in the CR-HR FLT3 MRD positive group (72%) followed by CR-HR FLT3 MRD negative (58%) and CR1/CR2 FLT3 MRD positive (39%). The risk of relapse was lowest (23%) for patients in CR1/CR2 with no evidence of FLT3 by PCR at the time of transplant (FLT3 MRD negative). Factors that did not influence the risk of relapse on univariate analysis included: age, donor source (HLA-matched related, HLA-matched unrelated, haploidentical and cord blood), stem cell source (peripheral blood vs. bone marrow), or conditioning intensity (myeloablative vs. reduced-intensity) (Table 2). On multivariate analysis, the only two independent factors associated with a higher risk of disease relapse were detectable disease by morphological examination and molecular detection of FLT3 MRD by PCR at the time of transplant (Table 2)

Figure 1.

A. Cumulative incidence of relapse according to disease status on morphologic analysis and FLT3 status at the time of transplant. 1B. Progression-free survival according to disease status on morphologic analysis and FLT3 status at the time of transplant

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for risk of relapse and progression-free survival

| Univariate analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Risk of relapse | Progression-free survival | ||||

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age (>50 years versus ≤50 years) | 1.1 | 0.7-1.8 | 0.6 | 0.94 | 0.6-1.4 | 0.7 |

| Karnofsky performance status (>80% versus ≤80%) | 0.7 | 0.45-1.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3-0.7 | <0.001 |

| FLT3 status at time of transplant (positive versus negative) | 5.1 | 3.1-8.5 | <0.001 | 4.4 | 2.96-6.7 | <0.001 |

| Hematopoietic cell transplant–comorbidity index score (≥4 versus 0/1) | 1.5 | 0.9-2.7 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 1.2-2.9 | 0.009 |

| Disease status at transplant | ||||||

| CR2 versus CR1 | 0.7 | 0.2-2.2 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.7-2.96 | 0.3 |

| CR-HR versus CR1 | 4.3 | 2.2-8 | <0.001 | 3.9 | 2.3-6.6 | <0.001 |

| Active morphologic disease versus CR1 | 6.5 | 3.7-11 | <0.001 | 5.9 | 3.7-9.3 | <0.001 |

| Donor source | ||||||

| Matched unrelated versus matched related | 1.6 | 0.9-2.8 | 0.09 | 1.6 | 1.0-2.6 | 0.04 |

| Mismatched unrelated versus matched related | 1.2 | 0.5-2.9 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 0.97-3.5 | 0.06 |

| Haploidentical versus matched related | 0.5 | 0.1-2.2 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.4-2.5 | 0.9 |

| Cord blood versus matched related | 1.9 | 0.9-4.2 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 1.2-4.3 | 0.01 |

| Graft source, excluding cord blood (peripheral blood versus bone marrow) | 0.9 | 0.6-1.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.6-1.3 | 0.4 |

| FLT3 mutation type (ITD versus TKD mutation at 835) | 2.5 | 1.0-6.3 | 0.05 | 1.99 | 1.0-3.9 | 0.05 |

| Conditioning intensity (reduced intensity versus myeloablative) | 1.1 | 0.6-2.0 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.7-1.9 | 0.5 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Risk of relapse | Progression-free survival | ||||

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| CR-HR and FLT3 negative | 2.9 | 1.2-7.2 | 0.02 | NS | ||

| CR-HR and FLT3 positive | 7.5 | 3.4-17 | <0.001 | 7.2 | 3.7-14 | <0.001 |

| Active morphologic disease present at time of transplant | 7 | 3.9-12 | <0.001 | 4.5 | 2.8-7.1 | <0.001 |

| Karnofsky performance status ≤80 | 2.1 | 1.4-3.3 | <0.001 | |||

| Hematopoietic cell transplant–comorbidity index score ≥4 | 1.6 | 0.99-2.6 | 0.05 | |||

| Unrelated donor | 1.7 | 0.98-2.8 | 0.06 | 1.6 | 0.99-2.4 | 0.05 |

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; CR1: first complete remission; CR2: second complete remission; CR-HR: high-risk complete remission; ITD: internal tandem duplication; TKD: tyrosine kinase domain; NS: not significant

Non-relapse mortality

Compared to patients in CR1, NRM was higher in patients in CR2 (hazard ratio [HR] 3.0, p=0.02), patients in CR-HR (HR 3.2, p=0.02), and patients with AD (HR 2.9, p=0.03). Patients with a Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) less than or equal to 80% had higher NRM compared to patients with KPS > 80% (P < 0.001). Also, NRM was higher in patients going to transplant with detectable FLT3 by PCR (HR 2.9, p=0.004) than patients without detectable FLT3 by PCR. The factors that did not influence NRM were age, hematopoietic cell transplant–comorbidity index score, donor source, conditioning intensity (ablative versus reduced intensity), and stem cell source.

On multivariate analysis, KPS ≤ 80% (HR 4, p=0.001) and patients not in CR with detectable FLT3 by PCR at transplant (HR 3.6, p=0.001) were independently associated with a higher risk of NRM (HR 5.1, p<0.001). The causes of NRM in this cohort were graft-versus-host disease (n=10, 9%), infection (n=9, 8%), regimen-related toxicity (n=8, 7%), graft failure (n=1, 1%), and other causes (n=7, 6%).

Survival

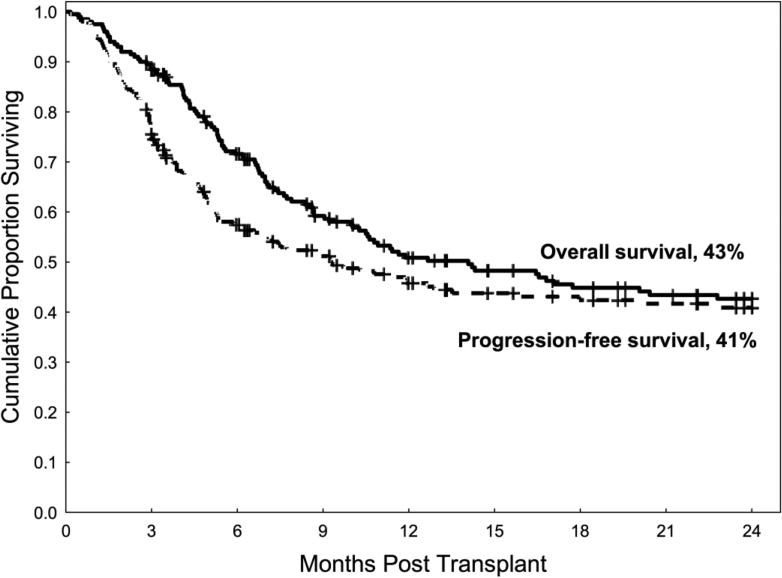

The median follow-up among survivors was 27 months (range 3-139 months), and the 2-year overall survival and PFS rates for the entire group were 43% and 41%, respectively (Figure 2). One hundred ten patients died, and leukemia relapse was the most common cause of death (n=75, 68% of deaths).

Figure 2.

Overall survival and progression-free survival

Morphologic and molecular disease status at the time of transplant were significantly associated with PFS. PFS was not significantly worse for patients in CR2 than in patients in CR1 (HR 1.5, p=0.3); however, PFS was lower in patients in CR-HR (HR 3.9, p<0.001) and patients with disease detected by morphologic analysis (HR 5.9, p<0.001) than in patients in CR1 (Table 2). The FLT3 MRD molecular detection by PCR at the time of transplant was also an important factor influencing PFS. Patients in CR1 or CR2 who were FLT3 MRD negative by PCR patients had higher PFS (62%) than patients in CR1 or CR2 who were FLT3 MRD positive by PCR (41%, p=0.3), patients in CR-HR who were FLT3 MRD negative by PCR (33%, p=0.01) and with CR-HR who were FLT3 MRD positive by PCR (0%, p<0.01), and patients with AD (8%, p<0.01) (Figure 1B).

On multivariate analysis, independent predictors of worse PFS included disease detected by morphologic examination (HR 4.5, p<0.001), CR-HR with FLT3 MRD positive by PCR (HR 7.2, p<0.001), Karnofsky performance scale status of ≤80 (HR 2.1, p<0.001), hematopoietic cell transplant–comorbidity index of ≥4 (HR 1.6, p=0.05), and an unrelated donor source (matched unrelated donor or cord blood) compared with a related donor source (matched sibling or haploidentical) (HR 1.6, p=0.05) (Table 2). No significant association was identified between PFS and age above 50 years, conditioning intensity, or stem cell source (peripheral blood versus bone marrow).

Discussion

We investigated the role of mutated FLT3 detected by PCR as an MRD marker, evaluated immediately before transplant, on transplant outcomes in patients with FLT3-AML undergoing SCT, and found that disease status before transplant measured not only morphologically but also molecularly independently influenced the risk of leukemia relapse and survival after transplant in these patients. Detection of mutated FLT3 by PCR before transplant was associated with higher relapse risk and worse survival in all pre-transplant morphologic disease status groups, suggesting that detecting FLT3 by PCR is a useful tool to better assess MRD prior to transplant and stratifies these patients by relapse risk more effectively than morphologic examination alone.

In general, the risk of disease relapse post-transplant is highest among patients with evidence of residual disease assessed by morphologic analysis at the time of transplant.[17] In our study, the depth of remission, assessed morphologically and molecularly, shortly before transplant was significantly associated with the risk of leukemia relapse after transplant. Patients with evidence of morphologic disease present at the time of transplant had the highest risk of relapse (85%), followed by patients in CR-HR, while patients in CR1 or CR2 at the time of transplant had the lowest risk of relapse rate, as predicted. Similarly, molecular disease status before transplant, represented by mutated FLT3 detected by conventional PCR, was a useful MRD marker, as this measure further stratified patients by risk of relapse. Patients in CR1 or CR2 with FLT3 MRD negative disease by PCR at the time of transplant had the lowest incidence of relapse after transplant (23%) and excellent survival, suggesting a beneficial effect of SCT for these patients. Similarly, the molecular remission status was useful in patients with CR-HR. In this group, patients with detectable FLT3 MRD by PCR before transplant had a very high incidence of leukemic relapse (72%), similar to that in patients with morphologic evidence of disease (>5% blasts) before transplant. Conversely, patients in CR-HR without detectable FLT3 MRD measured by PCR had a relatively lower risk of disease relapse (58%) and better PFS than their FLT3 MRD positive counterparts.

Collectively, these findings suggest that FLT3 MRD testing before and after transplant on conventional PCR may be a useful tool to predict disease relapse. While MRD detection can be a useful tool to predict early disease relapse post-transplant [17], FLT3 testing by conventional PCR has generally not been regarded as a good MRD marker given its relatively low sensitivity.[13, 14] Several smaller studies have shown that patient-specific FLT3 ITD testing by PCR can be an effective MRD marker; however, this technique is not widely available.[18, 19] Our analysis provides a rationale that testing for FLT3 by conventional PCR as a marker for MRD may have a role in identifying patients at high risk of relapse post-transplant. This finding, if verified prospectively, would be particularly useful to guide preemptive interventions after transplant, such as maintenance therapy post-transplant (e.g., azacitidine or FLT3 inhibitors). A number of FLT3 inhibitors are currently being investigated, and some have shown promising results.[20] Moreover, newer FLT3 detection techniques, such as next-generation sequencing or newer PCR testing methodology, might further improve detection sensitivity and render mutated FLT3 a useful MRD marker.[21-23] For example, Grunwald et al recently reported a relapse rate of 86% in a group of FLT3 mutated AML patients with detectable FLT3 by tandem duplication PCR but not by conventional PCR.[23]

Our study also highlights the effects of FLT3 mutation type and donor source on outcomes after transplant. The prognostic significance of FLT3 ITD versus FLT3 TKD mutations is controversial.[24, 25] We found no differences in outcomes between FLT3 ITD or FLT3 TKD mutations on multivariate analysis, although the numbers were small to make firm conclusions and this needs to be confirmed in larger studies. We also did not identify an effect of donor source on the risk of relapse. However, we did observe worse PFS and NRM in patients with unrelated donors than in patients with related donors. This difference between donor sources may seem counterintuitive since several studies have shown that the use of full human leukocyte antigen–matched unrelated donors led to outcomes similar to those from the use of matched sibling donors.[26] Our findings may be explained by the fact that our sample included patients treated over a long span of time, and high-resolution human leukocyte antigen typing has significantly improved over the past decade. Also, we found that patients with haploidentical donors had outcomes similar to those of patients with matched sibling donors. This result, although limited, supports several recent studies comparing haploidentical stem cellsources in patients receiving post-transplant cyclophosphamide with matched sibling donor or matched unrelated donor stem cell sources.[27-30] Together, these findings suggest that proceeding faster to transplantation with the first available donor should be considered, as postponing transplant can be detrimental.

There are several limitations to our study. First, this is a retrospective study, with its inherent biases. In addition, we were unable to correlate MRD represented by mutated FLT3 by PCR (which became readily available after 2000) with MRD detected by multi-color flow cytometry (routinely available after 2012). However, this is the largest study of patients with FLT3 mutated AML undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation to date and the first to detect a significant impact of MRD detected by PCR for the FLT3 mutations immediately pre-transplant, as well as an impact of disease detected by morphologic analysis, on relapse and survival. Ultimately, these findings will need to be confirmed in prospective trials.

In conclusion, in patients with FLT3 mutated AML, the degree of disease control, not only morphologically but also molecularly shortly before transplant is an influential factor predicting disease relapse post-transplant. By testing for FLT3 mutations by PCR pre-transplant, as a MRD marker, we were able to further risk stratify disease relapse post-transplant. Patients with morphological evidence of disease had extremely high rates of post-transplant relapse and newer approaches are needed in this group of patients. Several trials are currently evaluating post-transplant FLT3 inhibitors (NCT02400255, NCT01578109); and FLT3 MRD detection by PCR before or after transplant could help identify high-risk patients who would benefit from such early interventions.

Acknowledgments

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA016672, and this work used Cancer Center Support Grant shared resources. We are indebted to Sarah Bronson for excellent manuscript proof reading

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Presented in abstract form as an oral presentation at the American Society of Bone and Marrow Transplantation Meeting 2015, San Diego, California, USA.

Author Contributions

S.G and S.O.C designed the study; S.G. drafted the first manuscript draft; G.R. and J.C. prepared the data; R.G. performed the statistical analysis; B.O., J.E.B, A.M.A, P.K., D.M., U.R.P., B.S.A, E.J.S., E.J., N.D., M.A., F.R., J.C., K.P., R.E.C., and S.O.C reviewed and interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Thiede C, Steudel C, Mohr B, et al. Analysis of FLT3-activating mutations in 979 patients with acute myelogenous leukemia: association with FAB subtypes and identification of subgroups with poor prognosis. Blood. 2002;99:4326–4335. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song Y, Magenau J, Li Y, et al. FLT3 mutational status is an independent risk factor for adverse outcomes after allogeneic transplantation in AML. Bone marrow transplantation. 2015 doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayakawa F, Towatari M, Kiyoi H, et al. Tandem-duplicated Flt3 constitutively activates STAT5 and MAP kinase and introduces autonomous cell growth in IL-3-dependent cell lines. Oncogene. 2000;19:624–631. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandts CH, Sargin B, Rode M, et al. Constitutive activation of Akt by Flt3 internal tandem duplications is necessary for increased survival, proliferation, and myeloid transformation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9643–9650. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunet S, Labopin M, Esteve J, et al. Impact of FLT3 internal tandem duplication on the outcome of related and unrelated hematopoietic transplantation for adult acute myeloid leukemia in first remission: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:735–741. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.9868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma Y, Wu Y, Shen Z, et al. Is allogeneic transplantation really the best treatment for FLT3/ITD-positive acute myeloid leukemia? A systematic review. Clin Transplant. 2015;29:149–160. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gale RE, Hills R, Kottaridis PD, et al. No evidence that FLT3 status should be considered as an indicator for transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia (AML): an analysis of 1135 patients, excluding acute promyelocytic leukemia, from the UK MRC AML10 and 12 trials. Blood. 2005;106:3658–3665. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeZern AE, Sung A, Kim S, et al. Role of allogeneic transplantation for FLT3/ITD acute myeloid leukemia: outcomes from 133 consecutive newly diagnosed patients from a single institution. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1404–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunet S, Martino R, Sierra J. Hematopoietic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia with internal tandem duplication of FLT3 gene (FLT3/ITD). Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:195–204. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835ec91f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sengsayadeth SM, Jagasia M, Engelhardt BG, et al. Allo-SCT for high-risk AML-CR1 in the molecular era: impact of FLT3/ITD outweighs the conventional markers. Bone marrow transplantation. 2012;47:1535–1537. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlenk RF, Kayser S, Bullinger L, et al. Differential impact of allelic ratio and insertion site in FLT3-ITD-positive AML with respect to allogeneic transplantation. Blood. 2014;124:3441–3449. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-578070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araki D, Wood BL, Othus M, et al. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Time to Move Toward a Minimal Residual Disease-Based Definition of Complete Remission? J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy KM, Levis M, Hafez MJ, et al. Detection of FLT3 internal tandem duplication and D835 mutations by a multiplex polymerase chain reaction and capillary electrophoresis assay. The Journal of molecular diagnostics : JMD. 2003;5:96–102. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60458-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nazha A, Cortes J, Faderl S, et al. Activating internal tandem duplication mutations of the fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT3-ITD) at complete response and relapse in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2012;97:1242–1245. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.062638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin P, Jones D, Medeiros LJ, et al. Activating FLT3 mutations are detectable in chronic and blast phase of chronic myeloproliferative disorders other than chronic myeloid leukemia. American journal of clinical pathology. 2006;126:530–533. doi: 10.1309/JT5BE2L1FGG8P8Y6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walter RB, Gooley TA, Wood BL, et al. Impact of pretransplantation minimal residual disease, as detected by multiparametric flow cytometry, on outcome of myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1190–1197. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.8121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scholl S, Loncarevic IF, Krause C, et al. Minimal residual disease based on patient specific Flt3-ITD and -ITT mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2005;29:849–853. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiller J, Praulich I, Krings Rocha C, et al. Patient-specific analysis of FLT3 internal tandem duplications for the prognostication and monitoring of acute myeloid leukemia. European journal of haematology. 2012;89:53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2012.01785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stone RM, Mandrekar S, Sanford BL, et al. The Multi-Kinase Inhibitor Midostaurin (M) Prolongs Survival Compared with Placebo (P) in Combination with Daunorubicin (D)/Cytarabine (C) Induction (ind), High-Dose C Consolidation (consol), and As Maintenance (maint) Therapy in Newly Diagnosed Acute My.... Blood. 2015;126:6–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zuffa E, Franchini E, Papayannidis C, et al. Revealing very small FLT3 ITD mutated clones by ultra-deep sequencing analysis has important clinical implications in AML patients. Oncotarget. 2015;6:31284–31294. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bibault JE, Figeac M, Helevaut N, et al. Next-generation sequencing of FLT3 internal tandem duplications for minimal residual disease monitoring in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget. 2015;6:22812–22821. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunwald MR, Tseng LH, Lin MT, et al. Improved FLT3/ITD PCR assay predicts outcome following allogeneic transplant for AML. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yanada M, Matsuo K, Suzuki T, et al. Prognostic significance of FLT3 internal tandem duplication and tyrosine kinase domain mutations for acute myeloid leukemia: a meta-analysis. Leukemia. 2005;19:1345–1349. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mead AJ, Linch DC, Hills RK, et al. FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain mutations are biologically distinct from and have a significantly more favorable prognosis than FLT3 internal tandem duplications in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;110:1262–1270. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saber W, Opie S, Rizzo JD, et al. Outcomes after matched unrelated donor versus identical sibling hematopoietic cell transplantation in adults with acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2012;119:3908–3916. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-381699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciurea SO, Zhang MJ, Bacigalupo AA, et al. Haploidentical transplant with posttransplant cyclophosphamide vs matched unrelated donor transplant for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2015;126:1033–1040. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-04-639831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Stasi A, Milton DR, Poon LM, et al. Similar Transplantation Outcomes for Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndrome Patients with Haploidentical versus 10/10 Human Leukocyte Antigen-Matched Unrelated and Related Donors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bashey A, Zhang X, Sizemore CA, et al. T-cell-replete HLA-haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for hematologic malignancies using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide results in outcomes equivalent to those of contemporaneous HLA-matched related and unrelated donor transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1310–1316. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaballa S, Palmisiano N, Alpdogan O, et al. A Two-Step Haploidentical Versus a Two-Step Matched Related Allogeneic Myeloablative Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]