Abstract

Disclosure of a sexual or gender minority status has been associated with both positive and negative effects on wellbeing. Few studies have explored the disclosure and concealment process in young people. Interviews were conducted with 10 sexual and/or gender minority individuals, aged 18–22 years, of male birth sex. Data were analyzed qualitatively, yielding determinants and effects of disclosure and concealment. Determinants of disclosure included holding positive attitudes about one’s identity and an implicit devaluation of acceptance by society. Coming out was shown to have both positive and negative effects on communication and social support, and was associated with both increases and decreases in experiences of stigma. Determinants of concealment included lack of comfort with one’s identity and various motivations to avoid discrimination. Concealment was also related to hypervigilance and unique strategies of accessing social support. Results are discussed in light of their clinical implications.

Keywords: Homosexuality, Gender Identity, Young adults, Adolescents, Disclosure, Coming Out

Public identification with a stigmatized identity can result in acts of discrimination or rejection. Conversely, refraining from public association with a stigmatized identity that is relatively concealable can provide opportunities to circumvent discriminatory experiences. Thus, individuals who relate to concealable stigmatized identities (e.g., HIV positive serostatus, sexual minority status, mental health disorder, infertility status or previous abortion, Irritable Bowel Diseases or other stigmatized chronic health conditions, low-income level, gender identity [one’s subjective and potentially concealable sense of one’s gender] that falls outside societal conventions given one’s biological sex) may continually undergo complex decision making to manage the information they choose to present to their social environment. Visibility management (Lasser & Tharinger, 2003) refers to the dynamic process by which individuals with concealable stigmatized identities decide to whom and how they will disclose their identity in different environments. While each of the identities mentioned above carries with it a unique set of stressors, management of one has some generalizable features to others, which can include a concealable nature, a process of discovery and intrapersonal acknowledgement, and experiences with stigma (Corrigan, Larson, Hautamaki, Mattews, Kuwabara, Rafacz, Walton, Wassel, & Shaughnessy, 2009). Examination of this process may thus have implications for the mental health and wellbeing of multiple populations.

The “coming out” process among sexual minority individuals has been the subject of much research interest and has been considered an important developmental milestone in the U.S. (Mustanski, Kuper, & Greene, 2014). The process involves gaining an understanding of one’s sexual/ gender minority status, developing a social identity that incorporates LGBT status, and ultimately sharing this identity with others and redefining relationships to integrate this new information (D’Augelli, 1994). However, depending on the unique contexts of individuals and the resources available to them, coming out and remaining concealed can have both positive and negative effects on wellbeing. Minority Stress theory, which posits that sexual minority individuals are at an increased risk of experiencing mental health difficulties due to stressful experiences with discrimination and stigma, describes concealment as a minority stress process while at the same time describing the discrimination and victimization that can follow disclosure as minority stress processes as well (Meyer, 2003). We will now describe empirical work that has helped to elucidate these complexities.

With regard to potential health benefits, coming out has been associated with positive outcomes, including higher self-esteem (Rosario, Hunter, Maguen, Gwadz, & Smith, 2001). Self-disclosure has also been associated with fewer mental health problems, including emotional distress and conduct problems (Rosario et al., 2001). For individuals whose families react to their disclosure with acceptance, disclosure is associated with better social support systems and health, and fewer symptoms of depression, substance abuse, and suicidality (Ryan, Russell, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2010). When adolescents or young adults begin to express a public sexual or gender minority identity, their behaviors may fall more in line with their internal beliefs and attitudes, thus decreasing cognitive dissonance they may have experienced previous to disclosure (Pachankis & Goldfried, 2004; Lasser & Tharinger, 2003). Individuals who are “out” may also be more likely to participate in the LGBT community, which can help them to cultivate a unique and important source of social support (Doty, Willoughby, Lindahl, & Malik, 2010).

At the same time, disclosing a sexual or gender minority status can place individuals at increased risk for discrimination or rejection (Chesir-Teran & Hughes, 2009). This may leave some “out” LGBT young people at greater risk for experiencing mental health difficulties (Meyer, 2003). Indeed, LGBT youth generally experience more mental health difficulties than their heterosexual and cisgender peers (Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008). Developmental differences are also present in the literature. For example, individuals who disclose their sexual minority status at a younger age are more likely than those who disclose later to report victimization and other negative outcomes, including suicide attempts (e.g., Plӧderl et al., 2014). However, this same research also associates current outness with greater social support and decreased suicidal ideation, indicating that early disclosure may be a risk factor while later disclosure may be a protective factor, or, alternatively, that disclosure may entail negative short term effects (e.g., distress due to victimization) as well as positive longer term effects (e.g., open communication that facilitates social support).

Intrapersonal and contextual factors can have implications for the effects of disclosure. For example, coming out is negatively associated with health for inhibited, threat sensitive individuals (Cole, 2006) and is not associated with positive well-being for those who come out in contexts that do not support an individual’s autonomy (Legate, Ryan & Weinstein, 2012). The role of families is prominent, in that individuals who experience family rejection upon coming out are more likely to experience substance use (Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2009), sexual risk taking behaviors, depression and suicide attempts (Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009; Mustanski, Newcomb, & Garofalo, 2011) than those who disclose and experience no or low rejection from family. For these reasons, it is easy to see why some young people conceal their sexual or gender minority status.

However, keeping a key aspect of one’s identity concealed over time can have deleterious effects on well-being. Adolescence is a period when individuals gain a better understanding of their multiple identities and begin incorporating these identities into a cohesive whole (Erikson, 1959). However, coming of age in a heterosexist society can indoctrinate individuals from a young age to these stigmatizing attitudes, and thus deems it necessary to disentangle such attitudes from personal characteristics and experiences. Indeed, for individuals whose sexual identity deviates from the heterosexual norm, integrating a stigmatized identity into the whole self can be met with fear and shame (D’Augelli, 1994). During this time, to avoid social alienation, young people may portray a sexual identity that lays more in line with societal norms, but contradicts their internal attitudes and desires. This may lead to cognitive dissonance, avoiding contact with same-sex friends, and enacting sexual stigma toward others (Herek, Gillis, & Cogan, 2009). Over time, chronic concealment of a sexual or gender minority status may lead to social isolation and a denial of one’s sexual identity, both of which have negative effects on mental health (Pachankis, 2007). Prolonged concealment of a sexual minority status may also be related to internalized homonegativity, or self-stigma, wherein the LGBT individual internalizes society’s heterosexist value system and directs prejudice toward themselves and/or other LGBT individuals or groups (Herek, 2007). The literature regarding self-stigma and mental health is complex, though a recent meta-analysis indicates that internalized homonegativity is associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety (Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010).

Disclosure and concealment of a sexual and/or gender minority status thus involve complex calculations and cost-benefit analyses to determine the appropriate course of action for each individual in each of their unique social environments. This dynamic decision-making process may have important implications for the individual’s overall functioning and wellbeing. Despite these challenges, mental health disorders are far from ubiquitous among LGBT young people (Institute of Medicine, 2011). Research methodologies for ascertaining the prevalence of mental health disorders in sexual minority individuals are widely varied and imperfect (Meyer, 2003), but recent work with a sample of young, racially diverse, urban, sexual minority males indicated that 33.2% had lifetime major depression, 16.0% had lifetime PTSD, and 23.6% had lifetime conduct disorder (Burns, Ryan, Garofalo, Newcomb, & Mustanski, 2014). Although these figures are alarming, they also imply that a substantial number of young sexual minority individuals are resilient to the stressors related to visibility management and other effects of stigma. Gaining a better understanding of these resilience factors may help to promote the mental health of young sexual and gender minorities.

To date, previous research on concealment and disclosure includes descriptions about the types of disclosures individuals may undergo (e.g., therapeutic, relationship building, problem-solving, preventive; Cain, 1991), cognitive implications of concealment (e.g., emotional distress, hypervigilance; Pachankis, 2007), some explanations of the broader considerations that go into the decision to disclose (e.g., acceptance, community, comfort; Corrigan et al., 2009), disclosure styles (e.g., normalizing; Clair, Beatty, & Maclean, 2005) and other research tying one’s stage in LGB identity development to various factors related to disclosure (e.g., Whitman, Cormier, & Boyd, 2000). Research on disclosure among young people is limited however, and thus this investigation aims to better understand the considerations that young people consider while deciding to conceal or disclose their sexual and gender minority status.

In the current study, interviews were conducted with young people who appear resilient to minority stress. This is the first qualitative study to our knowledge to investigate disclosure and concealment processes among young sexual and gender minority people who have met an operationalized definition of resilience to psychological distress. The disclosure and concealment strategies mentioned by resilient young people may yield adaptive strategies that can aid others in the navigation of these complexities. Through in-depth interviews and qualitative analysis, we illuminate both why these individuals choose to disclose or conceal their stigmatized identities, and how they choose to do so. We explore methods employed by the young people to come out to others and probe their recommendations on the subject. We also investigate the perceived impacts that disclosure and concealment have on the individual’s social support network and experiences with stigma. By identifying the strategies and resources that these young people utilized in navigating identity management, we hope to inform interventions that can promote resiliency within the population. In summary, the current study aims to address the following three research questions:

What are the determinants of disclosure and concealment among resilient young sexual and gender minority people, and what factors do they recommend that other young people consider when making such decisions?

How do resilient young sexual and gender minority people disclose their stigmatized identities to others, and what methods do they recommend to other young people?

How do resilient youth perceive the effects of disclosure and concealment in terms of processes central to the Minority Stress model (e.g., self-stigma, stigmatizing events, and other stressors, as well as social support; Meyer 2003)?

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from Crew 450 (first reported in Mustanski, Johnson, Garofalo, Ryan, & Birkett, 2013), a longitudinal study of 450 individuals of male birth sex, who identify as gay or bisexual or have had sex with a man, and who were 16–20 years old upon enrollment. The current study also required that the participants were at least 18 years old. Lastly, at their two latest Crew 450 assessments (timed 6 months apart), participants must have reported experiencing at least one form of family-based discrimination (Ramirez-Valles, Kuhns, Campbell, & Diaz, 2010) in the past 6 months as well as subclinical levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms per a T score of less than 65 on the Achenbach Adult Self-Report Anxious/Depressed Syndrome Scale (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2003). Thus, resilience was operationalized as consistently maintaining sub-clinical anxiety/depressive symptoms despite repeated exposure to stigma from one or more family members.

Participants in Crew 450 who met these eligibility criteria were contacted via telephone by one of the study researchers. Potential participants were given a brief overview of the current study and asked whether they were interested in participating.

The sample size (N = 10) of the current study was determined to be the point at which researchers reached saturation. Saturation was operationalized as the point at which the coding of two consecutive interviews yielded either no new codes, or at most one new, largely idiosyncratic code per interview.

Procedure

Individuals who agreed to participate in the study met one of the researchers at one of two LGBT-focused community or health centers in a metropolitan Midwestern city according to the participant’s preference. In a private room, the study was discussed in detail with participants, and all the participants then provided informed consent. Each interview generally lasted between 60–90 minutes. Prior to beginning the interview, participants self-reported their current levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9 Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) and GAD-7 (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Lowe, 2006) to characterize the sample. After completing all questionnaires and the interview, each participant was given $35 cash and a resource list of LGBT-sensitive services available in the community.

The semi-structured interview consisted of open-ended questions regarding the participant’s: (1) social support networks, (2) personal attitudes toward their gender identity and/or sexual orientation, (3) experiences with discrimination, (4) coping behaviors, (5) experiences with coming out to others, and (6) family response to the participant’s gender identity and/or sexual orientation. Participants were asked questions such as, “How do you decide when and who to come out to?” “What, if anything, did you do to prepare yourself?” and “More specifically, and even if you never came out to them, did any of your family members call you names because of your sexual orientation or behavior?” See supplementary materials for the interview guide.

Interviews were transcribed from a combination of the audio recordings and interview notes using Express Scribe software. For one interview, the transcription was based solely on interview notes due to problems with audio recording. These audio problems were recognized prior to the interview’s start, and interviewer therefore took more detailed notes by hand.

Interview transcripts were uploaded to Dedoose, a web application for mixed methods research that allows application of codes to excerpts, calculations of internal reliability and visualizations of data. A codebook was developed iteratively using the constant comparative method (Taylor & Bogdan, 1998) in a style consistent with team-based qualitative coding (MacQueen, McLellan, Kay, & Milstein, 1998). Two researchers (LJB, MNB) open-coded the first two interviews independently to develop an initial version of the codebook. This version was then used to code all ten of the interview transcripts, though it was continually revised, refined and clarified throughout the process. Ten iterations of the codebook were developed in total to result in the final version, consisting of 44 dominant codes and 87 sub-axial items that represented sub-themes or components of the larger codes relevant to this analysis. All ten interviews were re-coded by each of two researchers (LJB, MNB) using the finalized codebook.

The codebook was created using a Critical Realist (Maxwell, 2012) approach to qualitative analysis, wherein the researchers recognized the study as an imperfect source of knowledge that is informed by the individual participant narratives as well as the researchers’ own preexisting knowledge on the subject. Thus, researchers utilized their knowledge of the Minority Stress Model (Meyer, 2003) and cognitive behavioral theory (Regehr, 2001) throughout the current study. The qualitative interview itself contained questions that were informed by both perspectives. These theories continued to inform development and refinement of the codebook.

Two interviews were randomly selected to determine inter-rater reliability on the dominant codes mid-way through the re-coding process. Inter-rater reliability was determined by the pooled kappa estimator, which is calculated using the observed inter-rater agreement averaged across all codes and the agreement expected by chance alone averaged across all codes (De Vries, Elliot, Kanouse, & Teleki, 2008). The first inter-rater reliability test was based off of 36 excerpts pulled from these two interviews and resulted in a pooled kappa agreement of .72 between the two coders, indicating substantial agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977). Due to the lengthy and dense dataset (transcripts averaged 20.2 pages and 11,307 words), the large number of potential coding constructs available, and the subtlety and nuance associated with many of the codes (e.g., labeling implicit attitudes or stressors), the researchers noted the high potential for discrepancy (Hruschka, Schwartz, St. John, Picone-Decaro, Jenkins, & Carey, 2004). Thus, the researchers reconciled all codes applied to every transcript, following independent coding by both researchers. Any discrepancies between the coders were resolved using the thoroughly operationalized codebook, thereby further refining and clarifying all coding constructs. Inter-rater reliability was repeated for 27 excerpts from the final two interview transcripts prior to reconciliation, resulting in a pooled kappa of .70 (Landis & Koch, 1977).

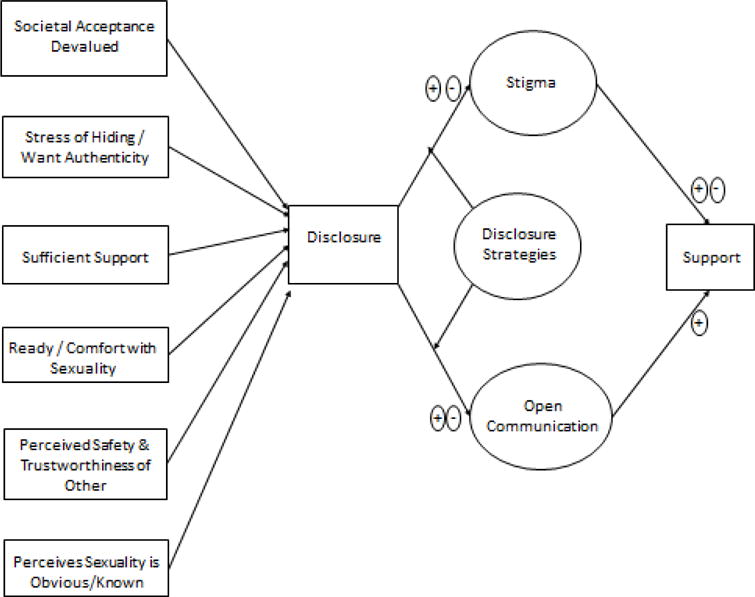

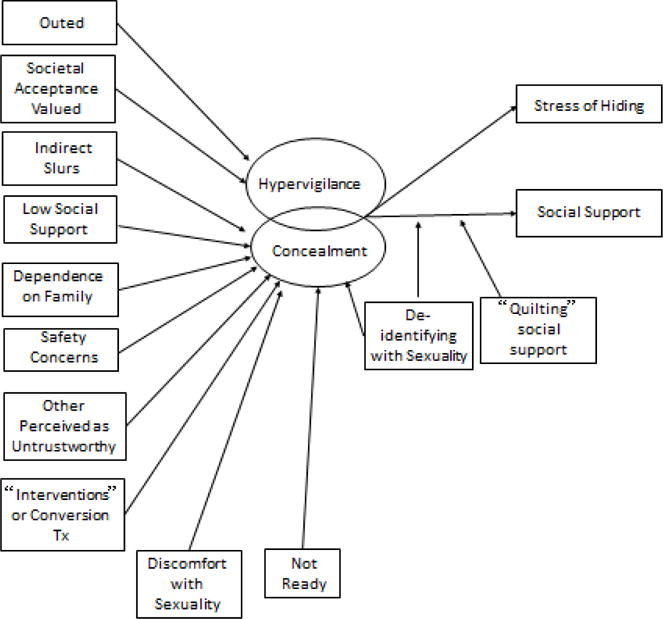

Next, the data was analyzed to explore potential determinants of concealment versus disclosure of sexual or gender minority status, as well as role flexing (i.e., modifying one’s behavior in heterosexist or potentially heterosexist contexts to avoid being stigmatized; Wilson & Miller, 2002). We also analyzed the data to determine how these processes may be related to social support and the experience of stigma (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

A Theoretical Framework for Disclosure of Sexual Minority Status

Figure 2.

A Theoretical Framework for Concealment of Sexual Minority Status

Results

We reached saturation after interviewing 10 participants. The sample (N=10) ranged in age from 18 to 22 years (M=20.2 years) and was ethnically and racially diverse: 4 participants identified as Hispanic/ Latino, 4 as non-Hispanic Black, and 2 as non-Hispanic White. Five identified as gay males, 3 as bisexual males, 1 as a gay, transgender female, and 1 as a bisexual, transgender female. Seven participants had disclosed their gender and/or sexual identities in all or most applicable life domains (e.g., work, school, family, friendships, religious organizations), per responses to the qualitative interview. T scores on the Achenbach Adult Self-Report Anxious/Depressed Syndrome Scale ranged from 50 to 60 over the participants’ two latest Crew 450 assessments. Self-report data (i.e., PHQ-9 and GAD-7) are missing for one participant due to a data entry error, and another participant is missing GAD-7 scores as they failed to answer one of the items. However, scores for the rest of the sample all fell in the none/minimal to mild symptom range and ranged from 0 to 6 for both measures (MPHQ-9= 2.89, Kroenke et al., 2001; MGAD-7= 2.88, Spitzer et al., 2006).

Disclosure of Sexual or Gender Minority Status

When asked about their stress levels before and after disclosure, five participants described a decrease in overall stress, two described experiencing a different type of stress (e.g., less stress regarding hiding, but more stress regarding other people’s reactions), and one cited an increase due to issues of personal safety. This is consistent with Minority Stress theory (Meyer, 2003) in that both concealment and potential sequelae of disclosure (e.g., stigmatizing events, expectations of rejection) are described as minority stressors. During the interview, the participants identified a variety of factors that they considered to be determinants of their disclosure in a particular context, either currently or in the past. The interview also yielded factors participants would recommend that other young sexual minority people consider when deciding whether to come out (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Determinants of Disclosure (N=10)

| Determinant | Participant Endorsements | Participant Recommendations | Participants who both endorsed and recommended | Quotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devaluation of Societal Acceptance | 7 | – | – | “I just live life, you know, honestly I really just do not care girl. I really do not. I am 21 years old, I am living my life for me, and at the end of the day… nobody can love me better than I can love myself.” –Participant 10 |

| Stress of Hiding | 3 (8*) | – | – | “I was like, it’s time. It’s time to tell them. I can’t, I can’t keep hiding secrets from my blood, my family.”—Participant 4 |

| Desire for Authenticity | 3 | 3 | 1 | “I was just tired of saying like no, I’m not gay, like denying that part of myself”—Participant 6 |

| Perceives Sufficient Social Support | 2 | 3 | 2 | “That safety net, like if it’s just a group of friends or the school that they go to, or someone in the family that already accepts them that they can go to”—Participant 6 |

| Sense of Readiness | 6 | 4 | 2 | “Baby you come out when you’re ready to come out. Don’t let somebody push you to come out.” – Participant 4 |

| Comfort with Identity | 3 | 2 | – | I was comfortable with myself and, it took me awhile to get to that point”—Participant 8 |

| Perceives Personal Safety | 2 | 2 | 1 | “Some things other people should think about….is, their safety. Because you can’t come out to any and everyone” –Participant 7 |

| Trustworthiness of other Individual | 5 | 7 | 5 | “Talking to the person that they feel the most comfortable with and like that they already know that like they won’t judge them or anything like that”—Participant 6 |

| Perceives the identity is obvious or known to others | 4 | 1 | 1 | “You’re just gonna wait five years, and then be like you’re gay and everyone’s like, yeah you know, why didn’t you tell us five years ago when we all knew already? So that’s, if everyone knows already sort of thing, just tell them.”—Participant 1 |

| Others directly asking | 4 | 1 | 1 | “I don’t mention it. If something comes up along the lines of, of my sexuality. Then, I mean ok. I’ll talk to you if you want to talk about it. If you don’t want to talk about it, fine.”—Participant 3 |

Number of participants who endorsed feeling stress before coming out, but who did not cite this stress as a direct determinant of their disclosure

Determinants of disclosure

For 6 of the 7 participants who had disclosed their sexual or gender minority status in most or all life domains, we observed a positive attitude and acceptance of their sexual and/or gender minority status (e.g., “I’m happy, I’m comfortable with it, I feel like there’s nothing that could possibly change on my end about what I want to do in life, who I date in life”–Participant 3). For the seventh participant who was out in most arenas, neither a positive nor negative attitude was noted. Three participants cited their comfort with their sexual or gender identity as a factor that influenced their decision to disclose, and two participants recommended that others gain an understanding and acceptance of their identity before sharing it with others.

Although participants did not explicitly link this next factor to their decisions to disclose, we noted that among the participants who had disclosed in all or most life domains, 6 out of 7 spontaneously evidenced a devaluation of general societal acceptance. The 7th participant expressed neither valuation nor devaluation of societal acceptance. One other participant who was out in several, but not all domains, endorsed devaluation of societal acceptance as well. There was a clear distinction between participants who disregarded societal acceptance (i.e., “I can get two rabbit’s butts about what anybody else thinks about me…you didn’t give birth to me, you’re not my friend…and you’re not gonna do anything to me, ‘cuz I’m gonna call the police… I know I’m beautiful baby; I’m not gonna let you sit here and let you try to bring me down.” – Participant 4) and those who largely valued it (i.e., “I want to be in the spotlight… I do want to be recognized. Where if I go somewhere, it’s like, ‘it’s him’…So, because of that, it’s like, you have the connotations of, ‘oh he’s gay’—some people like it, some people don’t like it…And all in all, I don’t want to be judged for my sexuality.”—Participant 9).

Eight participants described stress related to hiding their sexual or gender minority status in terms of behavioral (e.g., lying to family members, fearing related conversations), practical (e.g., dating), or personal authenticity (e.g., hiding one’s true self) challenges. For three of these eight participants, their decision to come out to others was related to their desire to eliminate these stressors from their lives. Related to this idea is the desire for authenticity, or a desire to express oneself completely. Three participants cited authenticity as one of the driving factors behind their own disclosure (e.g., “…I was like ‘this is my life, I control this.’ My mother did all that she had to do, my grandmother did all that she had to do, I’m gonna walk on my own two feet. I’m cooking with my own two hands, and I got my own mouth, I can use it.”–Participant 10), and three participants recommended that others consider the benefits of authenticity when deciding whether or not to disclose in specific arenas.

A sense of readiness sometimes preceded disclosure (6/10), and participants recommended that others consider their personal readiness prior to coming out (4/10). Three participants described a more subjective, internal state of readiness that drove their disclosure, and three participants described their consideration of a more structural state of readiness wherein they felt prepared to manage the possible consequences that might arise as a result of disclosure (i.e., “I talked it over with my sister and sat back and thought about it for a while. I weighed the pros and cons, thought about how they would feel—the reactions that I would possibly receive. Just, I guess, mentally prepare myself for it.”—Participant 3).

Two participants reported taking into consideration the amount of social support they had when deliberating whether or not to disclose (e.g., “I talked to my school’s um, social worker about, um oh like what if my family doesn’t accept me, what if they like do like the horror stories that you hear like they kick, they kick their kid out or whatever, so like I had pretty much my school’s support if anything.”—Participant 6). Three participants believed it was important for other young people to have a strong social support network that would continue to provide resources and emotional support, as well as buffer them from any negative consequences of disclosure (e.g., “And make sure you have a strong support group. Because if you have nobody behind you after, it’s going to be a really lonely experience which nobody should go through.”—Participant 8).

The perception of physical safety was related to coming out for two participants. Two participants also recommended that other young people consider their safety in different arenas before disclosing. Moreover, most (7/10) participants mentioned the trustworthiness of individuals they chose to come out to. Young people feel more comfortable coming out to individuals who appear trustworthy, unlikely to gossip, non-judgmental, and likely to react well to same-sex attraction. All participants mentioned safety, trustworthiness, or both, with the exception of a single participant who displayed a higher level of self-efficacy in seeking justice for perpetrators of discrimination: “I’m bisexual, you got a problem with it? You not gonna do nothing. If you put your hands on me, I’m calling the police.”—Participant 4.

Four of ten participants perceived their sexual minority status as obvious to others, such that they believed they no longer required a disclosure experience per se. Rather, they presume that other individuals correctly assume their sexual or gender identity either immediately upon meeting, or implicitly over time. In certain instances, individuals (4/10) typically only come out to others if asked for clarification regarding the sexual or gender identity.

Disclosure and communication

Disclosing a sexual minority status to others can have the effect of both opening and limiting communication. For example, two participants expressed relief at no longer feeling the need to lie to family members and others about important aspects of themselves or details of their day-to-day activities. For six participants, disclosure allowed them to speak more openly and honestly to the other individuals in their lives, including three participants who now had a forum to discuss and receive support regarding their sexual or gender minority status with similar individuals: “It was like, a sigh, that relief, that you have somebody else to talk to about stuff like that, that understands what you talkin’ about.”—Participant 5.

Disclosure of a sexual minority status was also a barrier to open communication in some relationships. For participants whose family members were not fully accepting of their sexual minority status, some (3/10) described relationship strain and reduced communication: “I can’t really like talk to my, I mean I can talk to my mom, but I don’t really… I can’t really do anything about it so. She’s not gonna change her mind, so. So that’s just sad but, something you have to deal with”. –Participant 1.

Participants cited several disclosure strategies that they had personally employed or that they would recommend to others, with the aim of maximizing the effect of disclosure on open communication with one’s social supports. Four participants mentioned the importance of coming out during meaningful conversations with others: “The late night talks that you have…you know that there’s always that moment where you’re like down to earth and you’re actually like talking about some stuff.”—Participant 1. Whether they were already organically involved in a more deep or sincere exchange, or whether they purposefully contrived meaningful scenarios, participants recommended these deep conversations as a good method of disclosure: “…just talk about it all sincerely and this is who I am and like, that’s just how it is.”—Participant 6. One participant also recommended coming out assertively. That participant believed it is important to stand up for oneself during the disclosure conversation, and that once beginning the conversation, one should be assertive throughout to ensure the message is heard.

Communication and support

Changes in communication between the young people and those to whom they came out appeared to affect the level of social support experienced. For two participants, disclosure that resulted in increased communication within a relationship also increased structural social support. For example, one participant described her mother’s reminders to take hormone replacement drugs or keep up with related medical appointments. Another participant indicated that his family newly felt that they could lend him money, as they trusted his responsibility in eventually returning loans. Disclosure and open communication can also increase the emotional support the individual experiences, for example one participant’s mother’s interest in his involvement with drag shows: “My mom…she was the only one that ever really was willing to listen to what I had to say about it… more openmindedness, more willing to be a part of it. Her trying to go through the experience with me, instead of watching from the sidelines.” – Participant 8. When individuals cited that disclosure had limited their communication with others, a subsequent loss of social support was associated (5/10): “I haven’t spoke to my auntie in months. She don’t even have my new number… the only time I see her is when I go home for Sundays and it’s a kiss on the cheek ‘hey auntie.’ I don’t even hold a conversation with her. That, that bothers me, because that’s my blood auntie.” – Participant 10.

Disclosure and stigma

Disclosing a sexual or gender minority status was related to both an increased experience of stigma and discrimination, and interestingly, at times a decrease in the stigma experienced by the participants. For example, five participants were hassled by family members to change gender non-conforming behaviors even after their disclosure, with one participant explicitly linking this treatment directly to disclosure: “when I did like come out… they noticed certain things more, obviously because they were looking for it… just natural habits that I had… they were seeing them through gay eyes now.” –Participant 1. Two participants were asked or encouraged to change their same-sex attractions and explore heterosexuality. One participant described being subjected to conversion therapy. Conversely, four participants described experiences where, prior to coming out, members of their family or social networks would make derogatory remarks about LGBT individuals. For three participants, after disclosing their own identification as LGBT, the individuals who had previously made such remarks refrained from doing so in the presence of the participants, and, in one case, apologized for their previous behavior. Thus, it appears that coming out can in some cases reduce the indirect discrimination young people experience.

The participants also mentioned strategies for disclosing a sexual minority status that aimed to minimize any stigma that may result. Many (8/10) of the participants recommended coming out in a controlled environment, though the definition of such was subjective and varied across the sample. For five individuals, a controlled environment compatible for disclosure was one that is private and intimate: “Privately, calmly, um, and make sure you use your words selectively. Because that’s not something that you bring out to the public, just because if it does go downhill, it could cause a scene, which, that’s not um, preferable,”–Participant 8. For two participants, a controlled environment was one that was more public: “Out to eat or something like, an occasion. I wouldn’t just bluntly like, there it is. I’d go and have dinner or lunch or something and you know, ease into it.”–Participant 7. Coming out to small groups of people or a single individual at a time was also recommended (2/10) over coming out to large groups of people, as a means of reducing the likelihood that somebody in the group might react negatively. However, one participant suggested coming out to family members all at once.

To ascertain how an individual is likely to respond to disclosure, some participants (3/10) recommended gauging how the individual feels about same-sex attraction by dropping hints or asking exploratory questions. One last disclosure strategy aimed to minimize stigma was emphasizing that one’s sexual orientation or gender identity was only one aspect of oneself, and that they were still the same person they always were (2/10): “Start a general conversation, ease your way into homosexuality, ease your way into gay people, how they feel about that, and go ahead and just, go ahead and knock it out. ‘Well, personally I’m gay, and you know, this is how I am’ and so on and so forth. That might just take their mind for the loop because the whole time they think they talking to somebody quote, unquote normal, and they see that gay people are normal people. We just sleep with each other. Same sex, that’s it, that’s it!”—Participant 10.

Stigma and social support

Experiencing stigma upon disclosing a sexual minority status and thereafter was found to decrease the amount of social support five individuals experienced in those relationships. For example, “For the longest time, for about two years [my dad] definitely made me feel rejected. I wasn’t invited to any family functions on his side of the family. I didn’t hear from him, like my other siblings have heard from him. Um, he definitely did a lot more for the other siblings than he did for me. I definitely did struggle with that a lot. And, I just eventually got tired of being taken care of, so I started doing things for myself.”—Participant 3. Interestingly, for one participant, an instance of discrimination brought him closer to family members and increased the social support he experienced. After being the victim of an armed robbery that he attributed to his gender non-conforming clothing, his parents recognized that they had nearly lost their son as a result of the robbery. Despite originally not accepting his sexual minority status, his family changed their attitude and approach toward him by offering more support and acceptance.

Concealment of a Sexual Minority Status

While 7 of the 10 participants had disclosed their sexual or gender minority status in all or most life domains, 3 participants concealed their sexual and gender minority status in key domains (e.g., one participant was out to family and some friends, but concealed to most strangers and acquaintances; one individual was out to some friends and coworkers, but concealed in family and close professional relationships; and one individual was concealed to almost everyone in his life). Also, participants who had already largely disclosed their sexual minority status to others were still quick to describe situations in which it would be better to remain concealed. The decision to conceal within specific life domains involved complex decision making related to a number of personal and environmental factors (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Determinants of Concealment (N=10)

| Determinant | Participant Endorsements | Participant Recommendations | Participants who both endorsed and recommended | Quotations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valuation of Societal Acceptance | 2 | – | – | “I just don’t like to let people down… I want people to um, to be, to look at me and say ‘hey he’s doin’ right,’ and say ‘hey he’s doin’ good.’”—Participant 9 |

| Insufficient Support System | – | 3 | – | “If you have nobody behind you after, it’s going to be a really lonely experience which nobody should go through”—Participant 8 |

| Dependence on Family | 2 | 2 | – | “If you have a family where you know, they’re gonna emancipate you or whatever… I would, I personally wouldn’t, I’d rather stay with my family.”—Participant 1 |

| Not Ready | 1 | 1 | – | “I’m not ready for nobody to know so I can’t be seen or hangin’ with somebody like that.”—Participant 5 |

| Discomfort with Identity | 2 | – | – | “I wasn’t comfortable with myself, I wasn’t, I mean it was, you know, during a time where I was just like, ‘I don’t know if it’s…right? wrong? I should do it, I shouldn’t do it?’”—Participant 1 |

| Safety Concerns | 2 | 2 | 1 | “You have a lot of negative people in the streets and you have to be careful who you tell things to because people plot every day.”—Participant 7 |

| Stigmatizing Individual | 4 | – | – | “You don’t come out to people that like ‘oh look at him, he walk like he gay’ and stuff like, no. Them will be the people that bring you down.”—Participant 5 |

| Trustworthiness of other Individual | 5 | 7 | 5 | “If I can tell that you at the party, and you’re trying to get everybody attention, and you tryin’ to be nosy and you come sit next to me on …You will not know my business, not even one time.” – Participant 10 |

| Conversion therapy | 1 | – | – | “I was lying too…But it was like, what am I supposed to do? You’re bringing me in, you’re sitting in this room, you just invited into this room and you’re gonna talk to me”—Participant 1 |

Determinants of concealment

Some determinants of concealment exist as a polar opposite to the determinants for disclosure. For example, of the three participants who largely concealed their sexual or gender identities, two displayed negative attitudes toward their own minority status (e.g., “another uncomfortable part about [my sexual orientation] is…that guys don’t want to be married. Guys cheat and there’s no consistency…”—Participant 9). No other participants cited negative attitudes toward their sexual or gender minority status, though two participants cited previous discomfort with their sexual minority status as a factor that drove their prior concealment. While devaluation of societal acceptance was related to disclosure, conversely, valuation of societal acceptance was associated with one participant whose sexual minority status remained largely concealed.

Perceived threats to one’s physical safety were also associated with concealment for two participants. One other participant described not yet being ready to come out because he was not ready to deal with the negative reactions he would likely receive. The perception that an individual is untrustworthy, likely to gossip, or likely to react to the news by stigmatizing the individual, was a factor in the concealment of five participants and recommended by six participants as an indicator that it would be better to remain concealed than to disclose. Another factor related to concealment that was mentioned by four participants was a previous experience of stigma via homonegative slurs that the participants had witnessed. For example, when these participants were in the presence of other people who denigrated LGBT individuals, the participants chose to maintain their concealment to avoid being the target of such treatment.

As participants weighed the importance of having sufficient social support before coming out, three participants recommended concealment for those whose support network is insufficient: “I had lots of friends, I was popular, people loved me. So if I came out it wasn’t a big deal. But if I was a loser in high school and no one liked me and I came out, and now you’re just more shunned, I think that might not be a good idea”—Participant 1. Another item that was associated with concealment was a high level of dependence on family members. Two participants recommended that other dependent young people remain concealed until a time of less structural dependence: “I’ve had friends [whose] parents have done that.. They’re not gonna pay for their college now ‘cuz their son’s gay. And I have friends who knew that and waited until they were out of college” –Participant 1. We also noted that two participants who did not yet have a clearly formed personal core identity, and who appeared to be sourcing important aspects of their identities from key relationship figures, remained concealed in most social environments.

Lastly, having been subjected to conversion therapy was also related to concealment for one individual in the study. Following that experience, the participant felt the need to maintain concealment within the family realm to avoid similar interventions in the future.

Concealment and hypervigilance

For two participants, maintaining concealment manifested as hypervigilance, or a heightened sensitivity to surroundings or state of awareness in order to maintain the status quo. A determinant of hypervigilance for one participant was having been previously outted (i.e., having one’s sexual orientation made public by others without one’s consent). This participant felt forced to convince others that this was not the case. Thus, the individual felt hyperaware of how others may be viewing him, and actively worked to minimize affiliation with a sexual minority status: “I usually don’t mess with people like of the same sex that I like, I usually mess with like straight dudes. So it’s like, they got more risk of getting busted than I do.”—Participant 5. This individual also endorsed stress that went along with these hiding behaviors. For the other participant who evidenced hypervigilance, a strong valuation of societal acceptance appeared to drive a generalized, guarded attitude toward the way he expressed his gender and sexuality, as well as how he felt others should express (or not express) theirs.

Concealment and social support

Concealing a sexual minority status had implications for the young people’s social support networks. Two individuals in the sample who remain largely concealed both stood to lose significant support from important individuals in their lives. Thus, concealment allowed these participants to maintain the current level of support in their lives. At the same time, concealment behaviors could interfere with the amount of social support an individual ultimately received. For example, one participant who remained concealed to the majority of his social supports found it necessary to use a strategy that we called “quilting.” He pieced together different social supports in his life, given that those supports were not sufficient in their own right. When describing how he approaches others to problem solve or get advice, he explained: “I just won’t never really tell the main, like the main reason. I’ll probably just like, beat around the bush to get a couple different answers or something. Then I’ll just end up dealing with it on my own.”—Participant 5. This behavior represents one strategy resilient young people may use to get the most from their support networks in the face of insufficient support. De-identifying oneself with a sexual minority status is another behavior that was shown to interfere with social support. By downplaying an affiliation with sexual minority status and avoiding these types of connection, two individuals limited the amount of belonging support they experience: “I can’t get into a relationship with a guy. Like ever now because that [being outted] just like, threw me off”—Participant 5. Despite the implications for social support, de-identification was crucial to the two participants who utilized this strategy to maintain and manage a concealed sexual minority status.

Role Flexing

Management of a sexual minority status is not a simple binary construct. Individuals may conceal in certain environments, but disclose freely in others. Indeed, role flexing appears to play an important role in the management process, wherein individuals highlight certain characteristics of themselves in specific environments while downplaying other features. Four participants endorsed role flexing behaviors, including downplaying their romantic life or attraction in certain public arenas, decreasing traditionally feminine gender expression, or displaying hypermasculinity at times. Several factors influenced the participants’ decision to role flex, including any specific, intolerant social contexts they encountered (n=2), or one participant’s generalized need for control in social contexts: “If I want to… be you know, be out here and be with a guy, I know how to control it. I know where to go with them, um, I know how to dress… how to act when I’m actually out.”—Participant 9. One participant evidenced a desire to minimize the perceived influence of his sexuality on other individuals. He believed that given his role model status to his younger cousins, it was important that they not pick up “any characteristics of homosexuality, I don’t want them to bite off that. I don’t want them to get that, I don’t want that for them because initially, if you’re not strong, you will try to kill yourself”. Thus, this particular participant used role flexing to try and shield others from experiencing the difficulties young sexual minority people may experience. Lastly, a perception of danger, rejection or harassment was cited as a reason for role flexing by two participants. Role flexing was said to result in increased pride due to viewing role flexing as a way to protect others (n=1), increased perceived control (n=1), increased perception of safety (n=2), and reduced exposure to stigma (n=2).

Discussion

Determining the contexts in which to conceal or disclose a sexual or gender minority status involves complex decision-making and cost/benefit assessment. While each participant exists in a unique context and thus employs relatively idiosyncratic internal and external resources, prominent themes emerged relating to individual identity management styles. Interviews revealed several factors that serve as determinants of disclosure or concealment in specific contexts. Participants also discussed effects of their individual identity management strategies, which resulted in both positive and negative consequences on social support systems, communication and experiences with stigma. Thus, the information presented appears to have specific and significant relation to wellbeing and mental health for young sexual minority people.

This investigation fills an important gap in the literature. Previous research on the subject of disclosure focuses largely on adult samples, and as a result, those findings may not generalize to young people. Further, qualitative studies among young people did not characterize their samples in terms of mental health, and thus it is more difficult to gauge the extent to which the strategies described are adaptive. The determinants that this investigation found to drive both disclosure and concealment corroborate previous research, for example Corrigan et al., 2009’s discussion of acceptance, community, and comfort driving disclosure among adults. At the same time, our examination yielded a broader range of determinants and coming out strategies that were gathered not only by individual endorsements, but also specific recommendations and advice that resilient young people wished to provide others. This rich dataset also enabled us to go beyond specific considerations and coming out strategies to explore the impacts, both positive and negative, that coming out and concealment can have on the day-to-day experiences of these participants.

The clinical implications of these findings are broad. Young LGBT individuals show increased rates of mental health difficulties compared to their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008). There is a call for a greater number of culturally sensitive mental health providers to treat the specific needs of LGBT people (Institute of Medicine, 2011), and understanding the complex processes behind identity management is crucial to providing culturally relevant support to young people in the midst of these deliberations. Disclosure is associated with both positive (Rosario et al., 2001) and negative (Cole, 2006) outcomes. Thus areas for clinical intervention depend on the specific needs of the patient, and whether disclosure or concealment is expected to be advantageous in their different life domains. Overall, this study illustrates a variety of potential positive and negative consequences of disclosure and concealment for which young people can prepare. The results also point to both positive and negative effects on one’s social support system and experiences of stigma that may come as a result of disclosure, both of which can have implications on wellbeing (Meyer, 2003; Hatzenbuehler, 2009).

Thus, a culturally-competent clinician must aid in the navigation of this terrain, coaching the young person and helping to determine whether internal assets and external resources are in place to buffer the stress associated with coming out or continued concealment. A first step might be to evaluate the client’s comfort with their sexual or gender minority identity, subjective and structural readiness, and plans for how they will cope with and manage potential consequences. For clients who decide to disclose, it may be helpful to guide the patient toward placing less emphasis on how society and others outside their family or support network view them (e.g., thinking through worst case scenarios). Other areas for intervention include helping young people attend to structural factors related to disclosure, for example identifying non-parental sources of structural support, ensuring sufficient social support, and creating a safety plan to protect themselves from those who may react negatively. For young people who may not have all of these assets in place, clinicians should help patients determine whether coming out in some, but not all environments is a possibility, such that the client can benefit from increased access to support from other LGBT individuals and a more uninhibited sense of self in specific arenas while still maintaining the safety of the status quo in less tolerant social domains. Aiding the client in the cognitive processing of experiences of discrimination and stigma could have important effects on wellbeing, due to the relationship between mental health difficulties and experiences with stigma. Future studies should examine the cognitive processes and coping skills that resilient young people utilize to maintain their wellbeing in the face of discrimination.

While the results at hand deal specifically with young, male-born sexual or gender minority individuals, these findings may generalize to other young people who experience similar identity management processes as a result of their own concealable stigmatized identities (e.g., sexual minority females, transgender males, young people aware of their HIV positive serostatus, young people with mental disorders, etc.). However, future studies are needed to determine the extent of the similarities in identity management processes between these groups.

Another limitation of this investigation is that, while some participants in the sample grew up in rural or suburban areas, all participants are currently living in a major metropolitan city. This may influence their day-to-day experiences with their sexual or gender minority status. Recruiting participants by telephone may also have affected the representativeness of the sample, for example by excluding young people who lack consistent phone service.

The results that are presented here are also reflective of the retrospective nature of many components in the semi-structured interview. While many deep, probing questions were asked by the interviewer to get a full understanding of participant accounts, it is possible that their answers were biased by the passing of time or other questions and topic areas included in the interview (e.g., questions regarding resilience and coping). Additionally, while many of the findings presented here were explicitly recognized or cited by participants to be important to identity management, the rich information gathered made it possible to infer relationships between certain factors, as per the nature of qualitative analysis. Thus, the analysis itself may have been biased or limited by the cognitive behavioral and Minority Stress theoretical perspectives that informed the coding. Finally, due to technical difficulties in audio recording one of the interviews, we had to rely on the interviewer notes rather than the exact words of the participant; thus, our theoretical perspectives may have biased or limited our coding of this interview more so than the others.

Conclusion

This was the first qualitative study to our knowledge that investigated identity management among young, resilient sexual and gender minority people. These young people consider a variety of internal and external factors before arriving at decisions to disclose or conceal their identity. This identity management represents a dynamic process that requires new evaluations upon each unique social environment. The resilient participants endorsed diverse strategies to navigate this process, and they provided recommendations for other young people on how to best navigate this complex experience. This investigation also described specific positive and negative effects disclosure and concealment can have on one’s social support systems and experiences with stigma. Taken together, these identity management strategies and recommendations can have broad implications for the wellbeing of young sexual and gender minority people.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01DA025548 (PI: Mustanski) and National Institute of Mental Health grant K08 MH094441 (PI: Burns)

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Adult Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Burns MN, Ryan DT, Garofalo R, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Mental health disorders in young urban sexual minority men. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;56:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain R. Stigma management and gay identity development. Social Work. 1991;36:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesir-Teran D, Hughes D. Heterosexism in high school and victimization among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:963–975. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9364-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clair JA, Beatty JE, Maclean TL. Out of sight but not out of mind: Managing invisible social identities in the workplace. Academy of Management Review. 2005;30:78–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW. Social threat, personal identity, and physical health in closeted gay men. In: Omoto A, Kurtzman HS, editors. Sexual orientation and mental health: Examining identity and development in lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. Washington, DC:: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 245–267. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Hautamaki J, Mattews A, Kuwabara S, Rafacz J, Walton J, Wassel A, O’Shaughnessy J. What lessons do coming out as gay men or lesbians have for people stigmatized by mental illness? Community Mental Health Journal. 2009;45:366–374. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR. Identity development and sexual orientation: Toward a model of lesbian, gay, and bisexual development. In: Trickett EJ, Watts RJ, Birman D, editors. Human diversity: Perspectives on people in context. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1994. pp. 312–333. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries H, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Teleki SS. Using pooled kappa to summarize interrater agreement across many items. Field Methods. 2008;20:272–282. [Google Scholar]

- Doty ND, Willoughby BLB, Lindahl KM, Malik NM. Sexuality related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:1134–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity and the life-cycle. Psychological Issues. 1959;1:18–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and the development of internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of LGB adolescents and their heterosexual peers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:1270–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin?” A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Gillis JR, Cogan JC. Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Garnets LD. Sexual orientation and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:353–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruschka DJ, Schwartz D, St John DC, Picone-Decaro E, Jenkins RA, Carey JW. Reliability in coding open-ended data: Lessons learned from HIV behavioral research. Field Methods. 2004;16:307–331. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) The Health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser J, Tharinger D. Visibility management in school and beyond: A qualitative study of gay, lesbian, bisexual youth. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26:233–244. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(02)00132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legate N, Ryan RM, Weinstein N. Is coming out always a ‘good thing?’ Exploring the relations of autonomy support, outness and wellness for lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2012;3:145–152. [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods. 1998;10:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JA. A Realist Approach for Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Johnson AK, Garofalo R, Ryan D, Birkett M. Perceived likelihood of using HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis medications among young men who have sex with men. Aids and Behavior. 2013;17:2173–2179. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0359-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Kuper L, Greene GJ. Development of sexual orientation and identity. In: Tolman DL, Diamond LM, editors. Handbook of Sexuality and Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2014. pp. 597–628. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Newcomb M, Garofalo R. Mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: A developmental resiliency perspective. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2011;23:204–225. doi: 10.1080/10538720.2011.561474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE. The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:328–345. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Goldfried MR. Clinical issues in working with lesbian, gay and bisexual clients. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2004;41:227–246. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J, Kuhns LM, Campbell RT, Diaz RM. Social integration and health: Community involvment, stigmatized identities, and sexual risk in Latino sexual minorities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:30–47. doi: 10.1177/0022146509361176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plӧderl M, Sellmeier M, Fartacek C, Pichler EM, Fartacek C, Kralovec K. Explaining the suicide risk of sexual minority individuals by contrasting the minority stress model with suicide models. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43:1559–1570. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regehr C. Cognitive-behavioral theory. Theoretical perspectives for direct social work practice: A generalist-eclectic approach. 2001:165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Hunter J, Maguen S, Gwadz M, Smith R. The coming out process and its adaptational and health-related associations among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Stipulation and exploration of a model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:133–160. doi: 10.1023/A:1005205630978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Disclosure of sexual orientation and subsequent substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Critical role of disclosure reactions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:175–184. doi: 10.1037/a0014284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, Sanchez J. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2010;23:205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SJ, Bogdan R. Introduction to qualitative research methods: A guidebook and resource. 3rd. New York: Wiley; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BDM, Miller RL. Strategies for managing heterosexism used among African American gay and bisexual men. Journal of Black Psychology. 2002;28:371–391. [Google Scholar]