Abstract

UWALK is a multi-strategy, multi-sector, theory-informed, community-wide approach using e and mHealth to promote physical activity in Alberta, Canada. The aim of UWALK is to promote physical activity, primarily via the accumulation of steps and flights of stairs, through a single over-arching brand. This paper describes the development of the UWALK program. A social ecological model and the social cognitive theory guided the development of key strategies, including the marketing and communication activities, establishing partnerships with key stakeholders, and e and mHealth programs. The program promotes the use of physical activity monitoring devices to self-monitor physical activity. This includes pedometers, electronic devices, and smartphone applications. In addition to entering physical activity data manually, the e and mHealth program provides the function for objective data to be automatically uploaded from select electronic devices (Fitbit®, Garmin and the smartphone application Moves) The RE-AIM framework is used to guide the evaluation of UWALK. Funding for the program commenced in February 2013. The UWALK brand was introduced on April 12, 2013 with the official launch, including the UWALK website on September 20, 2013. This paper describes the development and evaluation framework of a physical activity promotion program. This program has the potential for population level dissemination and uptake of an ecologically valid physical activity promotion program that is evidence-based and theoretically framed.

Keywords: Physical activity, Internet, Community, Evaluation, Theory, Health promotion

BACKGROUND

Regular physical activity provides a wealth of health benefits, including the prevention of chronic conditions such as, obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and some cancers [1]. In Canada, only 15 % of adults meet physical activity guidelines [2]. In a report released in 2014, it was estimated that by increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior in 10 % of Canadians with suboptimal levels of physical activity could result in a cost savings of $2.6 billion for the health care system by 2040 [3]. Thus, a significant need exists to develop evidence-based programs that have the potential to be widely disseminated to promote and subsequently increase population levels of physical activity.

Community-wide programs targeting improvements in health risk factors, such as physical inactivity, are an important public health approach for both primary and secondary disease prevention [4]. Such programs target behavior change across multiple levels of influence, reflecting the social ecological models [5, 6]. These interventions often involve targeting individual change, environmental approaches, and mass media. The inclusion of e and mHealth technology, which involves the communication of health information and care through the use of electronic and mobile devices [7], offer the potential to extend the reach of community-wide programs via increased convenience and flexibility [8]. The recent increases in widespread availability of electronic (e.g., Fitbit®) and more traditional activity (e.g., pedometers) monitoring devices have provided new opportunities for e and mHealth programs to promote physical activity. Evaluating the potential of these new technologies in public health is a critical next step to ensure this technology is being supported by evidence-based health research.

Previous community-wide programs have demonstrated potential in the area of population-level physical activity promotion. Two notable programs reporting success are “10,000 Steps Australia” and “10,000 Steps Ghent,” both of which are multi-strategy, multi-sector, community-based physical activity programs [9, 10]. For example, 10,000 Steps Australia began in 2001 as a government-academic partnership and was delivered throughout a regional community in Australia. After the initial follow-up period that was conducted in 2003, the researchers found significant program awareness, where 94.5 % of adults sampled had heard of the 10,000 Steps campaign in the intervention community compared to 34 % in the comparison community. A reduction in physical activity levels was also observed in the comparison community that was not evident in the intervention community [10, 11]. Based on the program’s success in building strong program awareness and maintaining physical activity levels in the intervention community, 10,000 Steps Australia continues to this day and has expanded globally. The program is now disseminated over the Internet and currently has over 300,000 members worldwide.

Though positive physical activity-related outcomes are associated with programs, such as those previously mentioned, there remains a lack of research systematically describing and evaluating real-world programs that bridge the gap between research and applied community settings [12, 13]. The RE-AIM framework provides an effective model to assist in developing and evaluating dissemination efforts and potential public health impact of health promotion programs [14]. This knowledge is required to develop and implement successful translational programs and to provide an understanding regarding factors related to the success of programs in natural settings.

The primary purpose of this paper is to describe the development and implementation of a multi-strategy, multi-sector, theoretically framed, community-wide physical activity promotion program (UWALK) using e and mHealth. The secondary purpose is to provide an overview of the evaluation framework being utilized (i.e., RE-AIM).

METHODS/DESIGN

UWALK background

In 2012, a government-academic partnership was developed between the Government of Alberta and the Faculty of Physical Education and Recreation at the University of Alberta. The Government committed $2.2 million (CAD) to the University to develop and implement a population-level health promotion program titled “UWALK” (www.uwalk.ca) from October 2012 to March 2016. Funding for the program commenced in February 2013, the UWALK brand was introduced on April 12, 2013 with the official launch, including the UWALK website on September 20, 2013.

The UWALK program aimed to build on the success of the existing 10,000 Steps program in Australia [11, 15] using a multi-strategy, multi-sector, theory-informed, community-wide approach to promote physical activity through a single over-arching brand. Alberta, Canada, was identified as the geographical target area (population = 3,645,257; land area = 640,081.87 km2; population density = 5.7 persons/km2, Statistics Canada, 2013) [16] for dissemination. However, due to the method of delivery (Internet), UWALK has the potential for national and international reach.

Two advisory boards were created, the Community Advisory Board (CAB) and a Research Evaluation and Advisory Board (REAB) to guide the development and evaluation of UWALK. The mandate of the advisory boards were to provide input and advice about the direction to be pursued with respect to strategies, initiatives, knowledge, research, and evaluation, in the context of UWALK’s strategic plan. Meetings were scheduled at least twice yearly for each advisory board to meet separately, with e-mail designated as the mode of communication when required outside of the scheduled meeting times. The REAB also served as a forum to facilitate opportunities for collaborative and/or new research initiatives that meet individual and/or organizational mandates.

Physical activity promotion and monitoring

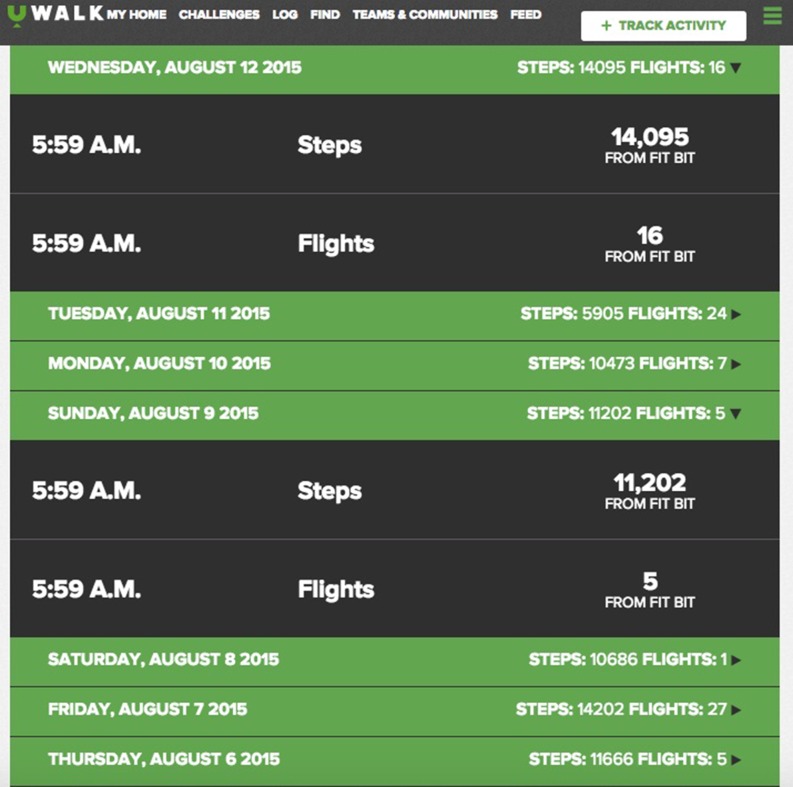

The purpose of UWALK was to promote physical activity with a focus on accumulating daily steps or flights of stairs. A major strategy was therefore to encourage individuals to use activity-monitoring devices (e.g., pedometers, commercially available electronic activity monitors, and smart phone applications) to self-monitor daily activity. UWALK was developed in a region featuring a cool continental climate, which features a relatively cold, dry winter. In Edmonton, one of the major cities in Alberta, the temperature during the winter months ranges from a daily average of −9.9 to −12.1 °C, with an average yearly snowfall of 118.1 cm [17]. As a result, UWALK included an indoor focus on the promotion of stair climbing in addition to the accumulation of daily steps. Consistent with previous research, stair climbing was operationalised as flights in the form of 10 steps/stairs are equivalent to 1 flight [18]. Total daily steps and flights were promoted as separate physical activity behaviors, encompassing their own distinct self-monitoring and goal-setting guidelines and instruments through the UWALK website. Limitations were not placed on members to use certain types of activity monitoring devices; members were able to manually input physical activity in the form of steps or minutes of physical activity with no limitations placed on the device used to record or obtain their physical activity information. In addition to the option of manually inputting physical activity data, however, the UWALK website included application programming interfaces (APIs) to automatically synchronise data from the Fitbit® and Garmin vivo series (vivoactive®, vivosmart®; Garmin Ltd., Olathe, KS) brand of electronic activity monitoring devices (Fitbit Inc.; Fig. 1) and the smartphone application Moves (ProtoGeo Oy) with member profiles. Fitbit products (One™, Charge™, Charge HR™, and Surge™) incorporate a tri-axial accelerometer with an altimeter that provides the ability to record physical activity in the form of steps and flights climbed. However, the Garmin vivo series activity monitors and the Moves application only synchronised step data to the website.

Fig 1.

Example screenshot to demonstrate API integration to automatically synchronise data from Fitbit® activity monitors to the UWALK website

Guiding frameworks

The development and evaluation of UWALK is based on several frameworks. The overall program was guided by a social ecological model (SEM) [19], which provides an effective framework for multi-strategy, multi-sector programs and has been used successfully in similar programs [9, 10]. An overview of key strategies identified upon the development of the UWALK program and their relative fit within the SEM is provided in Table 1. Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) was used to guide communication, such as informing promotional material and website development [20, 21]. SCT was chosen as it provides a good fit with SEM by acknowledging the reciprocal relationships between personal, behavioral, and environmental factors. Central to SCT are outcome expectations and self-efficacy, which can be targeted in order to produce behavior change. Self-efficacy is often acknowledged as the most important factor within the SCT [22]. Together, self-efficacy and outcome expectancies relate to a person’s belief that they have control over the behavior being targeted (i.e., physical activity), and that the benefits of performing the behavior outweigh potential negative aspects [20].

Table 1.

UWALK social ecological model implementation strategies and relevant links to program development categories

| Program development | Strategy | |

|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | Marketing and website | • Establishing an online selling portal for pedometers |

| • Loan of pedometer through public libraries | ||

| • Integrating website with other activity monitoring devices | ||

| • Establishing UWALK website | ||

| • Development of promotional material | ||

| Interpersonal | Marketing and website | • Promotion of physical activity through posters, videos and infographics |

| • Establishing a place for social connectedness on the UWALK website | ||

| • Establishing UWALK website | ||

| Organizational | Marketing, partnerships, and website | • Attending, assisting to organise and presenting at community events, partner events (health professionals, other health promotion programs) |

| • Targeting organizations (workplaces, primary care networks, etc.) to implement activity challenges | ||

| • Establishing an online selling portal for pedometers | ||

| • Establishing UWALK website | ||

| Community | Marketing | • Marketing campaign (videos, social media, and events) |

| • Environmental: Billboards, point of decision prompt posters and banners, including removable stickers promoting the use of stair climbing for elevators and stairs | ||

| • Loan of pedometer through public libraries | ||

| Policy | Marketing, partnerships, and website | • Sale and loan of pedometers |

| • Partnerships between local government, local health promotion programs, primary care networks, and adopting organizations |

Social marketing

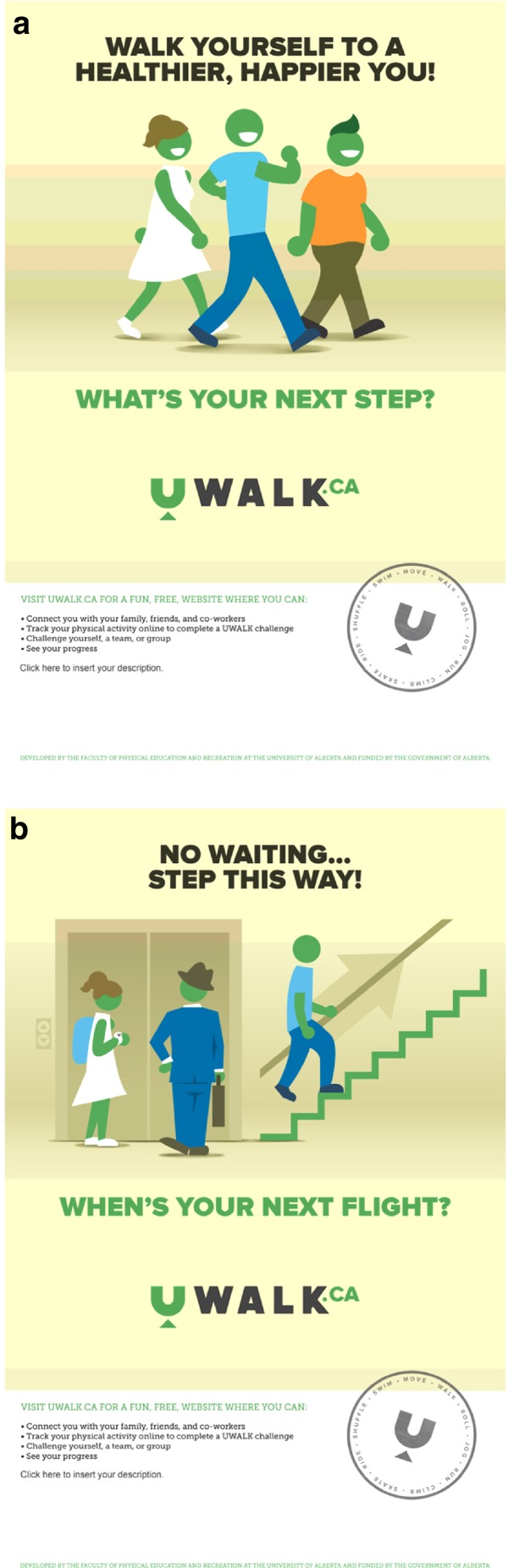

Marketing and communication strategies were being used to extend the reach and optimise effectiveness and adoption. These strategies were guided by the principles of social marketing as a strategic tool to establish and promote UWALK as a physical activity brand [23]. A key strategy of marketing activities was to promote physical activity and awareness of the UWALK brand to promote use of the UWALK website. This included a focus on branding and messaging through various promotional and social media activities. As part of establishing UWALK as a brand, a logo was created in multiple formats that allowed partners to customise the logo with their organisation name. Marketing material ended with the call to action to “Sign Up” on the UWALK website, along with the tag lines “What’s your next step?” or “When’s your next flight?”

Promotional material such as print advertisements, print material, and videos (Table 2; Fig. 2) were developed. Print material included posters, infographics, stickers, post cards, and door hangers. Print materials both promoted UWALK and fostered partnerships. For example, messages promoting stair climbing were developed as reusable stickers for partners (i.e., workplaces) to print, with the ability to personalise by adding company logo/name to promote stair climbing. Videos were also developed to promote awareness of the (1) UWALK brand and (2) physical activity with the purpose of directing people to the UWALK website (https://uwalk.ca/resources/videos/).

Table 2.

Overview of UWALK promotional material development

| Resource | Type |

|---|---|

| Billboards | “Walk With Us” sign |

| Videosa | Where are you doing it? |

| Are you doing it enough? | |

| Put a spring in your step | |

| When’s your next flight? | |

| Winter last wo(man) standingb | |

| UWALK in winter | |

| UWALK in your community | |

| UWALK at work | |

| How to UWALK | |

| Promotional | Pedometer branding |

| UWALK at work postcard | |

| UWALK in your community postcard | |

| Walking break door hanger | |

| Go for a walk door hanger | |

| Improve your mood with some fresh air poster | |

| Walk yourself to a healthier happier you | |

| No waiting, steps this way | |

| Climb your way to better health | |

| Infographics | Stair climbing infographic |

| Environmental | Posters to identify flights (1–20 flights) |

| Stair climbing reusable stickersc | |

| Partner resources | Logo and brand guidelines |

| Printable activity log | |

| Help guide for communities | |

| Community education PowerPoint | |

| Workplace education PowerPoint | |

| 2 × Library loan program posters | |

| Library pedometer packaging | |

| 3 × printable challenge maps |

aVideos are currently being disseminated through Vimeo and YouTube and imbedded on the UWALK website

bThe UWALK in Winter video was created as a general video and the Winter Last Wo(Man) Standing video has the same content as UWALK in Winter except it was used to promote one of the UWALK feature challenges and included challenge specific information at the end of the video

cAvailable in different sizes and colours

Fig 2.

Example of a walking and b stair climbing posters developed as part of UWALK promotional resources

Social media is a group of applications delivered online that provide a place for user-generated content to be created and exchanged [24]. Support has been provided for the use of social media in health promotion to increase access to programs, facilitate user interaction, and encourage social support [25]. Research into the effectiveness of using social media for health communication is in its infancy; to date, the majority of research has been conducted on developing social media interventions to produce health behavior change [26] and have yet to focus on the broader function of social media for social marketing such as the adoption of health promotion programs [27]. Social media applications utilised in the program include Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Vimeo as well as creating a space on the UWALK website for user-generated content and exchanges. Facebook and Twitter are two of the most popular social networking sites, with 1.49 billion and 316 million monthly active users, respectively [28, 29]. Facebook was selected to target the individual and reach a diverse group of people at a wide range of times. It was also used as an advertising platform for the UWALK program. This included the use of paid advertisements targeting Facebook users. Twitter was also used to target the individual and provides an ideal platform to support and build partnerships with other organisations and key stakeholders. YouTube and Vimeo were used to house and promote the UWALK Videos created.

Partnerships

A focus of the UWALK program was to establish partnerships with key stakeholders in the community, which is an important aspect in establishing effective community health promotion programs [30]. Such partnerships assist with extending the adoption and implementation of the UWALK program and can lead to maintenance of the program. Extending UWALK reach was an anticipated by-product of partnership engagement. Examples of partners included municipal governments, provincial governments, health care providers, communities, libraries, schools, workplaces, and existing physical activity promotion programs. The extent of partner involvement was dependent on the individual needs and intentions of each partner. In general, there were three levels of partner involvement; partners could be involved across more than one level. The first was the involvement in the conceptualisation and development of UWALK strategies (e.g., through becoming a member of the CAB or through information feedback and discussion with UWALK project staff). These partners were specifically targeted and invited to join the CAB, partners were identified through their involvement in the promotion of physical activity and health throughout Alberta and/or by providing a key link to the community. The second level of partner involvement included partners that had UWALK attend and promote the program at events. The final level was partners who registered on the UWALK website as a “Community” and implemented a physical activity challenge. Data was collected for types of partners registering with the Community function on the website.

Website

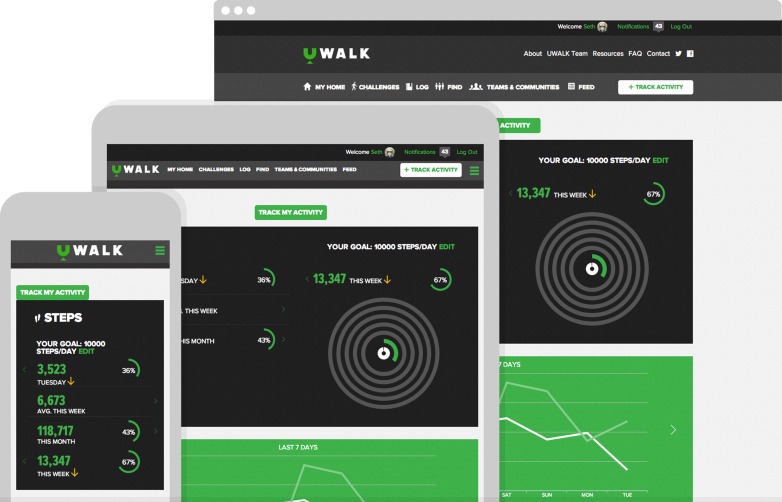

The website is an integral component of the e and mHealth aspects of the UWALK program and was the main method of communicating UWALK tools and resources. Instead of developing a separate mHealth application or “app,” which can be both resource- and financially intensive to maintain, the website included a responsive web design to ensure optimal accessibility and mHealth interaction across a range of devices (desktop, tablets, mobile phones; Fig. 3). Accordingly, the layout of the UWALK website was designed to adapt in response to the screen size of the device being used to access the website. Additionally, a shortcut could be created and saved as an icon on smartphone home screens to allow quick access, the icon would then appear on the home screen similar to any other mobile apps that are installed.

Fig 3.

Responsive web design demonstrated across desktop, tablet, and mobile device

Users could create UWALK member profiles on the website, which provided the function for members to log in to the website and access a secure personally relevant website with immediate access to all of the website tools. Members could engage with the website as individuals, teams and/or communities. After registering as an individual, UWALK members could create teams and communities, participate in interactive challenges, virtually interact with other UWALK members, and extend invitations to non-members to register for UWALK. Generally, members who create a community consist of a formal group that engage with UWALK as partners. Communities had the option of working together to complete an interactive challenge as a whole community or to create teams within their community to compete against one another as part of an interactive challenge/s. Members could also create teams that were not linked to specific communities; this function was targeted towards informal groups such as friends and family members to participate and compete against one another in interactive challenges. Finally, at the individual level, UWALK members could also complete challenges themselves or challenge other members to compete against one another in interactive challenges. Implementation guides were developed and made freely available as a resource on the website to clearly outline how to implement activity challenges.

As with the overall UWALK program, website development was guided by SEM and SCT. Additionally, the research team’s previous experiences in Web-based physical activity programs guided website development [15, 31–33]. Gamified elements were also incorporated into the website design to enhance user enjoyment and engagement [34]. Gamification is categorised as the use of video game elements to increase engagement and enjoyment in non-game contexts [35]. Examples of how gamification was operationalised on the website include story lines (e.g., the visual scenario of virtually climbing Mt. Athabasca, a mountain located in the Canadian Rocky Mountain), badges, leader boards, and interactive progress maps. A descriptive overview of some of the main website elements are provided in the following (also see Table 3).

Table 3.

Overview of UWALK website elements and linkages to the guiding theoretical frameworks (social ecological model, social cognitive theory, and gamification)

| Website element | Theoretical elements | Social ecological model level |

|---|---|---|

| Self-monitoring of physical activity | Gamification, goal-setting, outcome expectations | Intrapersonal |

| Physical activity goals | Gamification, goal-setting, motivation, self-efficacy | Intrapersonal |

| Interactive challenges | Gamification, goal-setting, motivation, self-efficacy | Intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, community |

| Physical activity feedback | Gamification, goal-setting, motivation, self-efficacy, | Intrapersonal, interpersonal |

| Badges | Gamification, goal-setting, motivation, self-efficacy | Intrapersonal, interpersonal |

| Social support | Gamification, motivation, self-efficacy | Intrapersonal, Interpersonal |

| Resources | Motivation, outcome expectations, self-efficacy | Intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, community, policy |

The types of physical activity self-monitoring that could be performed on the UWALK website include steps, user-reported moderate- and vigorous-intensity physical activity minutes and flights. These could consist of a combination of both subjective (e.g., moderate- and vigorous-intensity physical activity minutes) and objectively (e.g., steps or stair climbing from activity monitors) measured physical activity. Operational definitions of moderate and vigorous-intensity physical activity were included on the UWALK website to allow members to effectively categorise their physical activity intensity, definitions are consistent with those outline by the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology [36]. Moderate- and vigorous-intensity physical activity minutes were converted into step counts based on the compendium of physical activity [37], this enabled members to record a variety of physical activity types (e.g., swimming, cycling, weight lifting). The conversion for moderate physical activity was based on 100 steps per minute, with 200 steps per minute used for vigorous physical activity. Steps and converted steps from moderate- and vigorous-intensity physical activity were then converted to one daily physical activity total in the form of total steps per day. Though physical activity information could also be entered manually into the UWALK website, activity monitors including Fitbit®, the Garmin vivo series and Moves could be synchronised to an individual’s profile so that data could be automatically uploaded to the website.

Participants were able to set physical activity goals in the form of total daily steps and daily flights climbed. Based around the general recommendations for sufficient levels of physical activity required for health benefit, default goals were set for 10,000 steps per day and 10 flights [18, 38]. However, users could adjust goals based on current activity levels at any stage. Additional physical activity goals could be set when completing interactive challenges. Interactive challenges were developed for both step- and flight-based goals. Individuals could choose to participate in a challenge as an individual or as part of a team and/or community. Additionally, feedback and progress throughout interactive challenges was also provided. Individual graphical and numerical feedback was provided and personalised to each user’s progress based on their total daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly physical activity levels and in relation to physical activity goals. Additional personalized feedback was provided based on physical activity data for users participating in interactive challenges, this feedback included, challenge progress, challenge leader boards, visual progress on virtual challenge maps, and challenge checkpoints (which are progress markers at multiple points towards the end goal such as 10,000 and 20,000 steps on the way towards an end goal of 30,000 steps).

To build upon the gamified elements of the website, awards were provided to participants in the form of badges once they reached pre-defined achievements. Badges were based on both physical activity and website engagement achievements. Badges were also awarded for one off achievements and cumulative achievements. Examples include; 25,000 Badge for reaching 25,000 steps in a day, Weekly Warrior Badge for logging activity on the UWALK website for 7 consecutive days, Goal Stepper Badge for exceeding daily step total for 1 consecutive week and Sky Diver Badge for logging cumulative total of 1000 flights over membership lifetime. To encourage social support, social networking functions were built into the website. These included a personal feed which published the user’s physical activity data to their profile. Additionally, UWALK members were able to connect with one another by searching for a user’s profile and selecting to follow a user. This resulted in the followed user’s activity appearing on their feed and allowed them to comment on and like activity being generated to their feed.

In addition to providing behavioral support to individuals, the website served as a repository for UWALK promotional materials and resources which were freely accessible to the public. This section included downloadable versions of UWALK resources (see Table 3 for list of resources). It was also the gateway for the purchase of UWALK-branded pedometers.

Ethical considerations

The program was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta (Pro00041719). For the Computer-Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI) survey, the purpose of the survey is first explained and potential participants are then asked if they agree to participate. Agreement results in administration of the questionnaire. For data collection obtained from the UWALK website, members were able to freely use the website regardless of their decision to allow their data to be collected for research purposes. To provide potential members with this option, upon registration with the website, users could select not to have their data used for research purposes. Additionally, any member under the age of 16 years (as identified upon registration by providing date of birth) were required to provide a parent/guardian email address, an approval email is sent to their parent/guardian and access to the UWALK website was not granted until the parent/guardian has indicated approval through the relevant link embedded in the email. Users under the age of 16 years, although able to use the website, did not have any data collected for research purposes.

Program evaluation

The RE-AIM framework has been selected to use for program evaluation (Table 4). The five dimensions of the framework [39, 40] are compatible with the SEM [14]. Reach examines the number, proportion, and representativeness of the population aware of, and secondly, who are participating in the program; effectiveness examines the extent to which desired outcomes are achieved; adoption refers to the number and characteristics of target audience (at the individual and organizational level) that adopt the program; implementation examines how the program is implemented in the real world as originally intended; and maintenance measures the extent to which the program is able to be sustained over time and the long-term maintenance of program outcomes at an individual level. An overview of how each dimension of the RE-AIM is operationally defined, including measures and data sources being used to provide information relevant to outcomes is provided in Table 2. Briefly, reach is examined in three ways: firstly, it is represented by the percentage and characteristics of Albertans who are aware of the UWALK program, as captured through telephone surveys. Additionally, reach is being explored through UWALK website visits and growth of visits across geographic areas and UWALK social media growth throughout the duration of the program. Finally, total number of UWALK registered members and characteristics such as demographics and geographic locations of UWALK members will be explored. Effectiveness is primarily represented through physical activity levels of Albertans and awareness of UWALK. Additional measures to report on effectiveness include difference in physical activity levels between Albertans who are aware and unaware of UWALK and the effectiveness of UWALK challenges for increasing physical activity levels. This will be captured through the telephone surveys and online data collection using the UWALK website. In line with the RE-AIM framework organisational adoption is represented through the number of organizations/communities who register with UWALK and who run an activity challenge. Where possible, information on the percentage of the organization's employees or community's population who participate in challenges will be reported. This data will be extracted from the UWALK website database. Implementation is represented by obtaining feedback from a small sample of organisations/communities who have implemented a UWALK challenge. Feedback will include descriptions of how the challenge was delivered, resources used, costs involved, characteristics of organisation/communities implementing challenges, and recommendations for improvements. Maintenance is measured at both the individual and organizational level. At the individual level, trends in physical activity will be measured throughout Alberta on a yearly basis. The website use of UWALK members will also be reported on to reflect maintenance of engagement with the program. At the organizational level, maintenance will be measured using a small sample of organisations/communities who have implemented a UWALK challenge. The number of challenges implemented and future challenge intentions will reflect this. Additionally, website usage for challenge participants following the completion of challenges will be obtained through the UWALK database. Additional projects developed to fit under the UWALK banner involve separate evaluation methods to those outlined in the following. For instance, the Pedometer Library Loan Program, where public libraries throughout Alberta were approached to introduce a pedometer loan program in partnership with UWALK, has been developed and implemented to include a separate and distinct evaluation process.

Table 4.

Overall evaluation of the UWALK program according to the RE-AIM framework

| Outcome | Measure | Data Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reach | Percentage and characteristics of the population who were aware of the UWALK program Total UWALK members Percentage and characteristics of the population who are members of UWALK |

1. Awareness of UWALK (a) Demographic characteristics and location (b) Physical activity levels 2. Website visits and growth (a) Dates and locations 3. Social media growth (a) Dates and demographics 4. Number of UWALK members (a) Demographics |

1. Telephone surveys 2. Online data collection (Google analytics) 3. Online data collection (Facebook, Twitter) 4. Online data collection (UWALK) |

| Effectiveness | Descriptive information of Albertan physical activity levels and brand recognition Difference in PA levels between Albertans aware and unaware of UWALK Effectiveness of activity challenges for increasing activity levels |

1. Albertan physical activity levels 2. Awareness of UWALK 3. Baseline and post challenge activity levels (physical activity and stair climbing) (a) Demographics |

1. Telephone surveys 2. Telephone surveys 3. Online data collection (UWALK) |

| Adoption (Organizational) | Total number of organisations/communities and type of organisation who; (a) register with UWALK and (b) run a challenge. Where available percentage of organization/community population who participate in challenges being run by organisation |

1. Number of organizations/communities registered on the UWALK website (a) Type of organization (b) Details of activity challenge (c) Demographics |

1. Online data collection (UWALK) |

| Implementation | Descriptions on how the challenge was implemented and recommendations for improvements Adherence to the intervention by participants throughout the challenge |

1. Feedback from members who implemented challenge (a) Challenges implemented (b) UWALK resources used (c) Type of organization, setting, and target group 2. UWALK material developed (implementation guide, help guides, posters, video’s, etc.) (a) Number of times resources downloaded or viewed |

1. Online data collection (UWALK, Online questionnaires) 2. Online data collection (Google analytics, UWALK, Vimeo, YouTube) |

| Maintenance (individual) | Trends in physical activity levels throughout Alberta Length of website usage |

1. Albertan physical activity levels 2. Website usage |

1. Telephone surveys 2. Online data collection (UWALK) |

| Maintenance (organizational) | Maintenance of physical activity promotion after challenge completion Website usage post challenge completion by challenge participants |

1. Feedback from organisations/communities who implemented challenge and future challenge intentions 2. Website usage for challenge participants continuing to use website after challenge completion |

1. Online data collection (UWALK, Online questionnaires) 2. Online data collection (UWALK) |

CATI computer-assisted telephone interviews; PA physical activity

Measures broadly fit into the following two categories: telephone surveys and online data collection. These headings are used below to outline the proposed measures. Table 2 can be used as reference to link these measures to each RE-AIM element.

Telephone surveys

CATI data are being used to measure aspects of reach, effectiveness, and maintenance according to RE-AIM. To do this, cross-sectional data is being collected from the general public each year of the duration of the program (2013–2015) using a random sample of 1200 adults (18 years and older) throughout Alberta, Canada. Interviews are to be administered by landline telephone using CATI methods through the Population Research Laboratory (PRL) at the University of Alberta, Alberta, Canada. Data being collected include demographic, awareness and physical activity questions.

Awareness is measured by asking firstly unprompted, followed by prompted recall questions. The unprompted recall question asks “Are you aware of any programs that promote walking or physical activity in Alberta?” If yes, participants are then asked to name the programs they were aware of. The prompted recall question asks “Have you ever heard of UWALK Alberta?” These questions were adapted to the current program by previous research in the area [41, 42]. The survey includes a modified version of the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire and is scored according to the recommended protocols [43]. Participants are asked to report according to a typical 7-day period how many times a week, on average did they do the following kinds of activity for more than 15 min during their free time. Activities included “strenuous,” “moderate,” and “mild.” Each type of activity was asked separately and defined. Walking behavior is also assessed using a modified version (using walking questions only) of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) long form [44]. Walking questions capture duration (min) and frequency (days) of total walking and according to work, transport, and leisure domains.

Online data collection

Data is collected online through a number of methods including, Google Analytics, the UWALK website database, Facebook, Twitter, Vimeo, YouTube analytics, and online questionnaires. These analytics explore reach, effectiveness, adoption (individual and organizational) and implementation and maintenance (individual and organizational). Google Analytics capture summary data for website visits usage of pages within the website [45]. The UWALK website was developed to include a database structure to collect advanced website statistics that employs unique member identification numbers to monitor participant’s usage of the UWALK website (e.g., physical activity recorded, physical activity number of days, length of membership, length of website usage). In addition, upon registration with the UWALK, website users provided demographic information such as age, sex, and postal code. Partners who created teams or communities were also asked to provide information regarding the type of their organization (e.g., workplace, library, school) to ascertain program adoption (e.g., challenges created, number of participants).

Additional information will be collected from social media accounts including Facebook, Twitter, Vimeo, and YouTube. This will include page likes (Facebook), post performances (Facebook and Twitter), followers (Twitter), and number of views for promotional videos across Vimeo and YouTube. Online questionnaires using the FluidSurveys™ platform will be distributed to a sample of members who have implemented a UWALK physical activity challenge. The questionnaire will assess challenge implementation, benefits and barriers to challenge implementation, usefulness of the UWALK website and resources available, and future challenge intentions.

DISCUSSION

The overall goal of UWALK is to promote physical activity through a single over-arching brand, using a multi-strategy, multi-sector, and community-wide approach. Marketing and communication strategies, partnerships, and establishing a website were the main strategies of focus for initial program development and dissemination. Strategies targeted multiple levels and sectors to promote physical activity and establish the UWALK brand. Previous research has suggested a lack of information surrounding the development, implementation, and dissemination of health promotion programs [13, 46]. The current paper attempts to address this gap and provide information in terms of knowledge translation relevant to both researchers and professionals.

Similar to previous community-wide approaches to physical activity, the current program targets multiple levels of influence [5]. This includes the inclusion of social marketing activities and targeting the individual and environment. Strategies to target these multiple influences include the development of promotional videos, point-of decision prompt posters, environmental supports such as reusable stair stickers, and the UWALK website which facilitates self-monitoring of physical activity, social support, and activity challenges for individuals, workplaces, communities, and provides a repository of freely accessible UWALK resources and materials. Multi-level strategies have been used and advocated for by previous community programs including 10,000 Steps Australia and Ghent, Wheeling Walks, and Healthy Alberta Communities.

As identified previously, community-wide programs are extremely complex because they attempt to intervene on multiple levels, through different strategies and sectors in an effort to mobilize an entire community [47]. Therefore, it only stands to reason that the evaluation of such programs is equally complex. The RE-AIM framework is compatible with SEM and provides a good fit to assist in the design and evaluation of complex interventions with multiple components. At the completion of the initial 3.5-year funding period, the UWALK program will be evaluated according to the RE-AIM framework.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of UWALK is that it is an ecologically valid physical activity promotion program that is evidence-based and theoretically framed. Additional strengths include the focus on multiple strategies, collaboration with partners across multiple disciplines, and use of e and mHealth technology and evaluation activities to inform research and practice. The design of the program also holds advantages in terms of a scalable program that can result in dissemination and uptake at a population level.

UWALK also includes several limitations. Stringent timelines were placed on the UWALK program team for the dissemination of a number of promotional materials and resources making it difficult to undertake appropriate formative research. Though provincial (Alberta, Canada) physical activity is being measured, data collection includes self-report telephone surveys and there is no comparison community. As the telephone survey targets landline-based phone numbers, the ability to obtain data from younger adults (under 35 years old) may be limited due to the decline in landline telephone use in this population [48]. Additionally, as baseline data is collected in the same year (2013) that the program launched, it is possible that participants may have already been exposed to some intervention elements or may already be in possession of an activity monitoring device; however, this is anticipated to be minimal. The target population, although important, was difficult to define; the target geographical area was identified as Alberta, Canada. However, due to the use of the Internet, the program is dissemination nationally and internationally. Therefore, evaluation measures will include data from populations outside of Alberta. Where possible, this will be detailed; however, this will not be possible for certain measures such as data obtained from social networking sites (Twitter). Detailed research activities were not embedded in program aspects during the development phase, which reflects the real world nature of the program. A significant strength is the ecologically valid nature of the program, the results of which can provide important information to both researchers and professionals such as public health, local government, workplaces, and communities in terms of knowledge translation.

CONCLUSIONS

Throughout the program development and dissemination to date, there has been an emphasis on focusing resources and time on developing a variety of promotional material but a lack of focus on a major social marketing push. This could have implications on indicators of program success such as membership growth and brand awareness throughout the province. Further emphasis for the duration of the program should be placed on promoting UWALK to enhance awareness of the program. The results of the future RE-AIM evaluation will provide insight on the impact of a “real-world” population level physical activity program.

Acknowledgments

UWALK is a program developed by the Faculty of Physical Education and Recreation, University of Alberta, in partnership with the Alberta Centre for Active Living and a multitude of partners. Funding has been provided by the Government of Alberta. We thank the UWALK team past and present for their valuable contribution to the success of the UWALK program. MJD is supported by a Future Leader Fellowship (ID 100029) from the National Heart Foundation of Australia. GRM and VC are supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health New Investigator Award. TB is supported by the Canada Research Chairs program. JV is supported by the Canada Research Chairs program and a Population Health Investigator Award from Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions.

Author contributions

CJ and KM were involved in the initial grant application, conception of UWALK, establishing the methods, data collection and questionnaires, and implementation and dissemination of the program. All authors participated in the program design, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Implications:

Policy:

With the increase in use of technology for health promotion, ecologically valid, evidence-based programs can contribute to the knowledge base and provide significant insights to aid in the dissemination of such programs.

Research:

Providing information on the development of an ecologically valid physical activity promotion program and applying the RE-AIM evaluation framework is essential for knowledge transfer across research programs, settings, and populations.

Practice:

Providing an in-depth description of the development of a multi-strategy, community-wide physical activity promotion program can provide practical advice for the development of future population-level health promotion programs.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva, WHO; 2009.

- 2.Colley R, Garriguet D, Janssen I, Craig C, Clarke J, Tremblay M. Physical activity of Canadian adults: accelerometer results from the 2007 to 2009 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Stat Can. 2011; 22(1): 7–14. [PubMed]

- 3.Bounajm F, Dinh T, Theriault L. Moving ahead: making the case for healthy active living in Canada. Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada;2014.

- 4.Record NB, Onion DK, Prior RE, et al. Community-wide cardiovascular disease prevention programs and health outcomes in a rural county, 1970–2010. J Am Med Assoc. 2015; 313(2): 147–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Baker PR, Francis DP, Soares J, Weightman AL, Foster C. Community-wide interventions for increasing physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; 1: CD008366. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008366.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Spence JC, Lee RE. Toward a comprehensive model of physical activity. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2003; 4(1): 7–24.

- 7.World Health Organization. E-Health. 2015 [cited 2015 29 July]; Available from: http://www.who.int/trade/glossary/story021/en/.

- 8.Wei J, Hollin I, Kachnowski S. A review of the use of mobile phone text messaging in clinical and healthy behaviour interventions. J Telemed Telecare. 2011; 17(1): 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Brown WJ, Eakin E, Mummery K, Trost SG. 10,000 Steps Rockhampton: establishing a multi-strategy physical activity promotion project in a community. Health Promot J Austr. 2003; 14(2): 95–100.

- 10.De Cocker KA, De Bourdeaudhuij IM, Brown W, Cardon GM. Effects of “10,000 Steps Ghent” A whole-community intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2007; 33(6): 455–463. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Brown WJ, Mummery K, Eakin E, Schofield G. 10,000 Steps Rockhampton: evaluation of a whole community approach to improving population levels of physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2006; 3(1): 1.

- 12.Goode AD, Eakin EG. Dissemination of an evidence-based telephone-delivered lifestyle intervention: factors associated with successful implementation and evaluation. Transl Behav Med. 2013; 3(4): 351–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Gubbels JS, Mathisen FKS, Samdal O, et al. The assessment of ongoing community-based interventions to prevent obesity: lessons learned. BMC Public Health. 2015; 15(1): 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999; 89(9): 1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Mummery WK, Schofield G, Hinchliffe A, Joyner K, Brown W. Dissemination of a community-based physical activity project: the case of 10,000 steps. J Sci Med Sport. 2006; 9(5): 424–430. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Statistics Canada. Focus on geography series, 2011 Consus, S. Canada, Editor. 2012: Ottawa, Ontario.

- 17.Government of Canada. Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010 Station Data. 2015 [cited 2015 September, 10]; Available from: http://climate.weather.gc.ca/climate_normals/results_1981_2010_e.html?stnID=1865&lang=e&province=AB&provSubmit=go&page=26&dCode=1.

- 18.Paffenbarger RSJ, Hyde RT, Wing AL, Lee I-M, Jung DL, Kampert JB. The association of changes in physical-activity level and other lifestyle characteristics with mortality among men. N Engl J Med. 1993; 328(8): 538–545. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Behav. 1988; 15(4): 351–377. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

- 21.Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol Health. 1998; 13(4): 623–649.

- 22.McAuley E, Szabo A, Gothe N, Olson EA. Self-efficacy: implications for physical activity, function, and functional limitations in older adults. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011: 10.1177/1559827610392704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Grier S, Bryant CA. Social marketing in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005; 26(1): 319–339. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Kaplan AM, Haenlein M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus Horiz. 2010; 53(1): 59–68.

- 25.Hamm MP, Chisholm A, Shulhan J, et al. Social media use among patients and caregivers: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2013; 3(5): e002819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Balatsoukas P, Kennedy CM, Buchan I, Powell J, Ainsworth J. The role of social network technologies in online health promotion: a narrative review of theoretical and empirical factors influencing intervention effectiveness. J Med Internet Res. 2015; 17(6): e141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Schein R, Wilson K, Keelan JE. Literature review on effectiveness of the use of social media: a report for peel public health. 2011 [cited 2015 September 17]; Available from: https://www.peelregion.ca/health/resources/pdf/socialmedia.pdf.

- 28.Facebook Newsroom. Company Info. 2015 [cited 2015 September, 17]; Available from: http://newsroom.fb.com/company-info/.

- 29.Twitter. Company. 2015 [cited 2015 September, 17]; Available from: https://about.twitter.com/company.

- 30.Sorensen G, Emmons K, Hunt MK, Johnston D. Implications of the results of community intervention trials. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19(1):379–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jennings CA, Vandelanotte C, Caperchione CM, Mummery WK. Effectiveness of a web-based physical activity intervention for adults with Type 2 diabetes—a randomised controlled trial. Prev Med. 2014; 60: 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Davies C, Corry K, Van Itallie A, Vandelanotte C, Caperchione C, Mummery WK. Prospective associations between intervention components and website engagement in a publicly available physical activity website: the case of 10,000 Steps Australia. J Med Internet Res. 2012; 14(1): e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Davies C, Spence JC, Vandelanotte C, Caperchione CM, Mummery WK. Meta-analysis of Internet-delivered interventions to increase physical activity levels. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012; 9(1): 52 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Cugelman B. Gamification: what it is and why it matters to digital health behavior change developers. J Med Internet Res. 2013; 1(1): e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Deterding S, Sicart M, Nacke L, O’Hara K, Dixon D. Gamification using game-design elements in non-gaming contexts. in CHI’11 Extended abstracts on human factors in computing systems. ACM; 2011.

- 36.Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian physical activity guidelines Canadian sedentary behaviour guidelines. 2012 [cited 2016 January 10]; Available from: http://www.csep.ca/cmfiles/guidelines/csep_guidelines_handbook.pdf.

- 37.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000; 32(9; SUPP/1): S498–S504. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Tudor-Locke C, Hatano Y, Pangrazi RP, Kang M. Revisiting “how many steps are enough?”. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008; 40(7): S537. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE. The future of physical activity behavior change research: what is needed to improve translation of research into health promotion practice? Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2004; 32(2): 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Caperchione CM, Duncan M, Kolt GS, et al. Examining an Australian physical activity and nutrition intervention using RE-AIM. Health Promot Int. 2016; 31(2): 450–458. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Berry TR, Spence JC, Plotnikoff RC, et al. A mixed methods evaluation of televised health promotion advertisements targeted at older adults. Eval Program Plann. 2009; 32(3): 278–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Bauman A, Bowles HR, Huhman M, et al. Testing a hierarchy-of-effects model: pathways from awareness to outcomes in the VERB™ campaign 2002–2003. Am J Prev Med. 2008; 34(6, Supplement): S249–S256. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Godin G, Shephard RJ. Godin leisure-time exercise questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997; 29(6): S36–S38.

- 44.Craig C, Marshall A, Sjöström M, et al., and the IPAQ Consensus Group and the IPAQ Reliability and Validity Study Group. International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003; 35: 1381–1395. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Google. Google analytics. 2015; Available from: http://www.google.com/analytics.

- 46.Neuhaus M, Healy GN, Fjeldsoe BS, et al. Iterative development of Stand Up Australia: a multi-component intervention to reduce workplace sitting. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014; 11(1) 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Baker PR, Francis DP. Cochrane review: community-wide interventions for increasing physical activity. J Evid-Based Med. 2015; 8(1): 57–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Statistics Canada. Residential telephone service survey, 2013. 2014 [cited 2016 11 January]; Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/140623/dq140623a-eng.htm.