SUMMARY

We present an illness-death model for studying the incidence and the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. We argue that the illness-death model is better than a survival model for this purpose. In this model the best choice for the basic time-scale is age. Then we present extensions of this model for incorporating covariates and taking account of a possible effect of calendar time. Calendar time is introduced via a proportional intensity model. We give the likelihood for a mixed discrete-continuous observation pattern from this model: clinical status is observed at discrete visit-times while the date of death is observed exactly or right-censored. The penalized likelihood approach allows to non-parametrically estimating the transition intensities. Application on the data of the Paquid study allows to produce estimates of the age-specific incidence of dementia together with mortality rates of both demented and non-demented subjects. Then the effect of calendar time and educational level are studied. Low educational level increases the risk of dementia. The risk of dementia increases with calendar time while the mortality of demented decreases. The most likely explanation of this result seems to be in a shift in the diagnosis of dementia towards earlier stages of the disease prompted by a change in the perception of dementia and the arrival of new drugs.

Keywords: Alzheimer Disease; Dementia; France; Humans; Markov Chains; Models, Statistical

1. Introduction

For the purpose of estimating the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia and of understanding the relationship between incidence and prevalence, disease onset and death should be jointly modelled using an illness-death model. The aim of this paper is to describe such a model, to develop some approaches for statistical inference and to give some descriptive epidemiological results. The approach takes into account the discrete pattern of observations for the clinical status and investigates the possible trend of incidence and mortality rates with calendar time. This paper relies on previous work on interval censoring in survival data analysis [1–6] and on multistate models [7–9]. The analysis of interval-censored observations from multistate models was studied in some recent work [10–15]; we have given reviews of these works [16–17].

In section 2, models with increasing sophistication are presented: we argue that a survival model is not adapted to the study of dementia and that a satisfactory framework is that of an illness-death model. We present both a stationary model in which age is the basic time-scale and a model in which the transition intensities may depend on calendar time. In section 3 the problem of estimation of the model is treated. In section 4 results using different models applied to the data of the Paquid study, a cohort of 3672 subjects with 10 years of follow-up, are presented. Results using the stationary model give an idea of the age-specific incidence and the mortality rates of both demented and non-demented subjects. Then possible effect of calendar time is investigated. Separate analyses for men and women are presented and the effect of educational level is studied.

2. Model for clinical status

2.1. Modeling as a survival problem

In term of random variable, the distribution of age of onset T of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia can be modelled; the hazard function is considered as the age-specific incidence of the disease. In the following we will focuss on dementia rather than Alzheimer’s disease because treating Alzheimer’s disease raises the additional problem of what to do with subjects developing other types of dementia.

Modeling of onset of dementia can be put in terms of stochastic process. For each subject i we may define a process Xi as Xi(t) = 0 if subject is non-demented at t, Xi(t) = 1 if subject demented at t.

The hazard function for subject i is

But what is the role of dead subjects? Are they right-censored? This problem can not be neglected because Alzheimer’s disease essentially occurs in persons older than 65 so that the mortality rates are high; in fact, as can be seen from figures 2 and 3 they are higher than the incidence of dementia. Here we are not dealing with patterns of observations but with models for the clinical status of the subject: censoring pertains to the observation pattern, while death is a clinical status not represented in this model. If death is treated as a censoring variable, this means that we observe (for a subject dying without dementia) that the time of onset of dementia is larger than the time of death. But this has really no meaning since a subject who is dead can not develop dementia. The hazard function would represent the risk of developing dementia marginally relatively to the vital status, and it is not clear wether this can be interpreted as the incidence of dementia. If we want to have a clearly interpretable model we must avoid the confusion between pattern of observation and clinical status. Another point of view is that if death is treated as censoring, then it is an informative censoring. This informativeness comes from the differential mortality between demented and non-demented subjects and leads to biased estimates of the age-specific incidence as has been shown in Joly et al. [15].

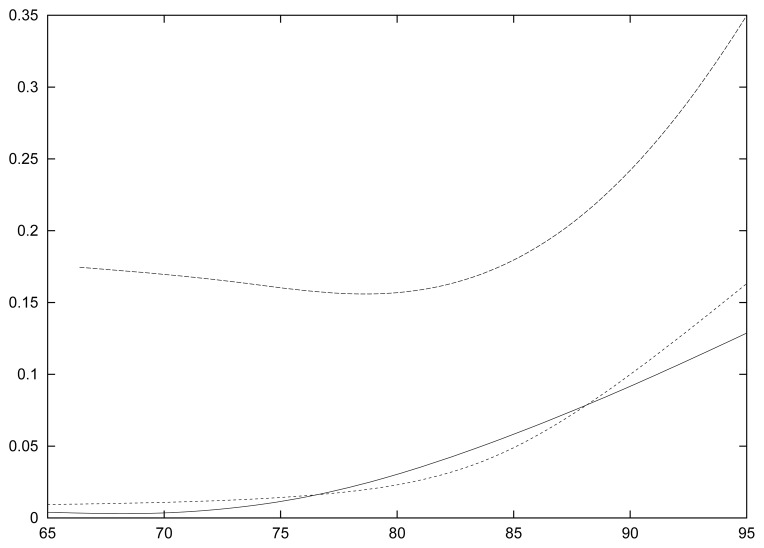

Figure 2.

Age-specific incidence of dementia and mortality rates for women. Upper dotted line: mortality rate for demented; lower dotted line: mortality rate for non-demented; continuous line: incidence of dementia.

Figure 3.

Age-specific incidence of dementia and mortality rates for men. Upper dotted line: mortality rate for demented; lower dotted line: mortality rate for non-demented; continuous line: incidence of dementia.

2.2. A Markov illness-death model

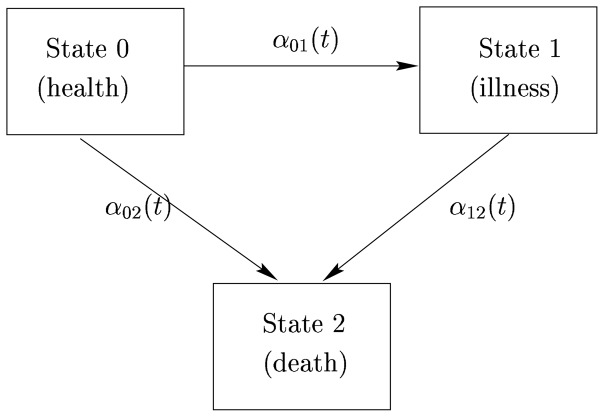

In an illness-death model death is represented explicitly in the model. Each subject gives rise to a stochastic process Xi(t) which takes the value 0 if subject is alive and not demented, 1 is subject is alive and demented and 2 if subject is dead at time t (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of an illness-death model.

The transition intensities can be considered as a generalisation of the hazard function: they quantify the risk of going from one state to another and they characterize the model. For instance the transition intensity from health to dementia is defined as:

Similar definition can be given for and .

Now to specify the model we must tell what is t and how depend on i. We shall consider a first model in which t represents age; this means that for each subject we choose the origin of time as being defined by the birth of the subject. This choice is motivated by the a priori knowledge that the risk of dementia and the mortality rates essentially depend on age of the subjects. These intensities may also depend on calendar time and we shall study this possibility later; for the moment we will consider a “stationary” model in which the intensities do not depend on calendar time. Now let us consider a model in which the intensities of all the subjects are the same for the same age: . This may have two interpretations: either the subjects have really the same intensities (risks) or this is the (marginal) intensity of a subject taken at random in the population.

The common (or marginal) transition intensity α01(t) can really be considered as the (instantaneous) age-specific incidence of dementia. Indeed consider a large population of size N; the subjects of this population do not need to be born at the same calendar time since we assume here that the intensities do not depend on calendar time. The incidence at age t for a time period Δ can be defined as the number of new cases during [t, t + Δ] divided by the number of persons at risk. we have:

For N large: and . Thus:

for small Δt. If Δt is the time unit, for instance one year:

Similarly, α02(t) and α12(t) can be interpreted as age-specific mortality rate for non-demented and demented subjects respectively.

Age-specific prevalence of dementia is

In our model for a large population this is equal to:

The probabilities that X is in a given state can be written in terms of transition intensities:

where are the cumulative intensities; we have also that P(X(t) = 2) = 1 − P(X(t) = 1) − P(X(t) = 0).

2.3. Covariates; the proportional intensity model

The heterogeneity between the subjects can be explained in part by factors which can be coded by explanatory variables. Then a general model is:

that is the heterogeneity is explained by the value of Zi(t), a vector of possibly time-dependent explanatory variables which are supposed to be completely observed. In that case, the subjects share the baseline functions αhj0(.) and functions ϕhj (which define the type of model and generally involves a set of regression parameter vectors βhj). The population can be said homogeneous, conditionally on the Zi(t),t ≥ 0. An assumption which greatly simplifies the model for inference with continuous time observations is the proportional intensity assumption: αhj(t, Zi(t)) = αhj0(t)rhj(Zi(t)); a common choice is , where βhj is a vector of regression coefficients. The regression coefficients are in principle different from one transition to another, although some constraints can be put to reduce the total number of parameters.

2.4. Time-scales

There are mainly two other times which could influence the values of the transition intensities: calendar time and, for demented, time since onset of dementia. The mortality rate of demented subjects, α12, could depend not only on age but on time since onset of dementia: di(t) = t − T1i, where T1i is the time of onset of dementia. Thus the mortality rate at time t of a demented subject i (given that he became demented at T1i) would be α12(t, di(t)). One possibility would be a semi-parametric model using a proportional intensity model: α12(t,di(t)) = α120(t)eβhjdi(t). (This model is no more Markov but semi-Markov; we will not pursue this path in the following and will remain in the framework of non-homogeneous Markov models.)

Intensities may also depend on calendar time. Since we have then two times we may choose one or the other as basic time scale. In a sense it would be more natural to take as basic time scale the universal calendar time; however since in all this paper age is the most important time we will keep it as basic time-scale, still denoted by t. We will denote calendar time by ci(t) because of the relationship linking calendar time and age for subject i: ci(t) = t + bi, where bi is the (calendar) time of birth for subject i(bi = ci(0)); thus ci(t) represents the calendar time when subject i has age t. The transition intensities may then be written αhj(t, ci(t)), considering that the function αhj(.,.) is shared by all the subjects. A proportional intensity model may be used for calendar time considered as a time-dependent variable:

With the proportional intensity modeling and because of the relation ci(t) = t+bi the problem can be simplified to a model with a fixed explanatory variable since:

In the application we shall in particular consider a proportional intensity model with fixed covariates;

This possibility of expressing the effect of calendar time as the effect of birth date leads us to discuss the distinction between calendar time effect and cohort effect. Calendar time effect summarizes the effects of factors present at calendar time c such as viruses or drugs available at time c; this can also be an “effect” due to the way the disease is diagnosed at time c. The cohort effect more directly relates to the time of birth and to the subsequent experiences subjects born at a certain time have undertaken. For instance subjects born in 1910 have experienced the first world war while subjects born in 1930 have not; they also have experienced slightly different medical and educational systems during all their lifes. Although the concepts are different, the two effects are indistinguishable in the proportional intensity model when age is the basic time-scale, as appears from the above equations. In many models including age there is little information, although there could be some information if particular shapes of these effects far from the proportional intensity model were considered.

3. Model for the observation process

3.1. Selection of the sample

For making inference we must have a sample. This sample is always selected according to a particular design which has to be taken into account for inference. We will focuss on the most common design in which a random sample of a target population is taken and then is followed-up during several years. Clinical status is generally assessed at prespecified visits and vital status can be observed in continuous time. For studying dementia, the target population may be the population of subjects aged more than 65 living in a certain region. For being selected subjects must be alive at time V0 of the initial visit. If age is the basic time-scale V0 is the age at initial visit which is different from one subject to another; we omit the superscript i for simplicity. This is a left-truncation condition : X(V0) ≠ 2. Often the truncation condition is extended by excluding the demented subjects at the initial visit because it is difficult to have a representative sample of demented subjects; in that case the truncation condition becomes: X(V0) = 0 (subjects have to be alive and non-demented to be included).

3.2. Observation times

Observation of the processes may be in discrete or in continuous time. The most common pattern of observation in studies on dementia is a mixed discrete-continuous one in which the clinical status is observed at discrete visit times V0, V1, …, Vm, while the date of death can be retrieved nearly exactly. We shall assume that the visit times are prespecified, thus that part of the mechanism leading to incomplete data can be ignored. Most often there are also missing data: that is a subject should have been seen at Vj say, but could not because of refusal or change of adress. In that case the missing at random assumption is questionable: for instance demented subjects may refuse more often than non-demented.

4. Estimation

4.1. Likelihood

We give the likelihood for the illness-death model for the truncation condition X(V0) = 0 and assuming missing at random data; the likelihood is given for one subject, dropping the i subscript for simplicity (all the quantities namely phj, αhj, V0, VL, Vj−1, T̃, δ, may depend on i); the global likelihood for observation of a sample of n independent subjects will be the product of the n individual likelihoods. Observations of X are taken at V0, V1,…, VL and the vital status is observed until C (C ≥ VL); here VL is the last visit time of an alive subject. Let us call T̃ the follow-up time that is T̃ = min(T, C), where T is the time of death; we observe T̃ and δ = I{T ≤ C}.

The likelihood can be most naturally written in term of both transition intensities αhj and transition probabilities phj(s, t) = P(X(t) = j|X(s) = h). If the subject starts in state “health”, has never been observed in the “illness” state and was last seen at visit L (at time VL) the likelihood is:

if the subject has been observed in the illness state for the first time at VJ then the likelihood is:

That this is the likelihood has been rigorously proved in [18]. The transition probabilities are linked to the transition intensities by the formulas:

where is the cumulative intensity between s ans t.

4.2. Maximization of the likelihood

Classical inference requires the maximization of the likelihood. For parametric model the likelihood can be maximized without problem using for instance a robust Newton-Raphson algorithm. Some work has been done for non-restricted non-parametric inference by Frydman [11–13], who proposed an EM algrithm. An attractive approach is to use a smooth non-parametric approach such that achieved by penalized likelihood [14–15]. In the semi-parametric case where one baseline function is estimated for each transition, the penalized likelihood is:

where l is the loglikelihood, α(.) is the matrix of baseline hazard functions, β is the array of vectors of regression parameters βhj, D represents the data. The penalty term excludes that discrete or unsmooth functions maximize pl(α(.), β, D). The solution of the penalized likelihood is approximated using a basis of splines and can also be computed using a robust Newton-Raphson algorithm. The computation are simpler when there is no time-dependent variables because it is possible to represent the transition intensities on a basis of B-splines and the cumulative intensities on a base of I-splines with the same coefficients, thus avoiding some numerical integrals [5].

A common problem of all the smoothing methods is to choose the degree of smoothness of the estimators. Cross-validation has been the most often used method. In an illness-death model, one has to maximize the cross-validation criterion LCV(κ01, κ02, κ12) on the three smoothing parameters; this is difficult but may be done approximately by grid methods.

There has been relatively few works on the asymptotic properties of this approach: some results on the asymptotic properties of the penalized likelihood have been given by Gu [19] but to our knowledge, nothing has been published on the properties of the approach combining penalized likelihood and cross-validation. However several simulation studies [5, 14, 15, 20] have shown good empirical properties of these estimators.

5. Results from the Paquid study

5.1. The Paquid study

The application is based on the Paquid research programme [21], a prospective cohort study of mental and physical aging that evaluates social environment and health status. The target population consists of subjects aged 65 years and older living at home in southwestern France. The baseline variables registered included socio-demographic factors, medical history and psychometric tests. Diagnosis of dementia was made according to a two stage procedure: the psychologist who filled the questionnaire screened the subjects as possibly demented according to DSM-III-R or not; subjects classified as positive were later seen by a neurologist who confirmed (or not) the diagnosis of dementia and made a more specific diagnosis, assessing in particular the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for Alzheimer’s disease. Subjects were re-evaluated 1, 3, 5 and 8 and 10 years after the initial visit. Prevalent cases were removed from the sample because it was more difficult to have a representative sample of a population including demented people. Therefore, this produced a left-truncation problem. The sample consisted of 3675 subjects. During the 10 years of follow-up, 437 incident cases of dementia were observed of whom 161 died; 1299 subjects were observed in the healthy state at the last visit before death (due to the interval censoring part of them may have developed dementia before death without being observed demented). An analysis had been made using a three-state progressive model for trying to estimate the mortality rate in demented subjects [22]. Here we used the more adapted illness-death model, first using the stationary version, then including calendar time. We used the penalized likelihood approach depicted in section 4.2 and using cubic splines with 7 knots for the approximation of each intensity function; the parameters were estimated using a robust version of the Newton-Raphson algorithm.

5.2. Incidence estimation assuming stationarity

Figures 2 and 3 show the three transition intensities for women and men respectively. All these curves rise steadily with age except the mortality rate for demented women which is stable until 85. The mortality of demented is much higher than that of the non-demented subjects with a pattern not far from an additive risk model, the additional risk being about 0.2 for both men and women, a very large increase indeed. Also it can be seen that the mortality rate and the risk of dementia are about the same in women while the mortality rate is higher than the risk of dementia in men.

5.3. Study of the effect of calendar time

The mortality rate of non-demented subjects may decrease in calendar time (due to mixture of conditions at c and conditions experienced before c); mortality rate of demented subjects may decrease due to better medical care or to earlier detection of dementia. Incidence of dementia could depend on calendar time for several reasons: i) risk factors of dementia may have changed in time: for instance increasing education level should lead to a decrease of α01; new risk factors may appear, for instance prion disease may interfere with dementia; ii) decrease of mortality rates may lead to less selected subjects at given age, thus more frail for dementia; iii) perception of the disease in the population and by medical doctors (general practitioners and neurologists as well) has changed while application of DSM-III-R criteria for dementia remains subjective (we shall return to this in the discussion).

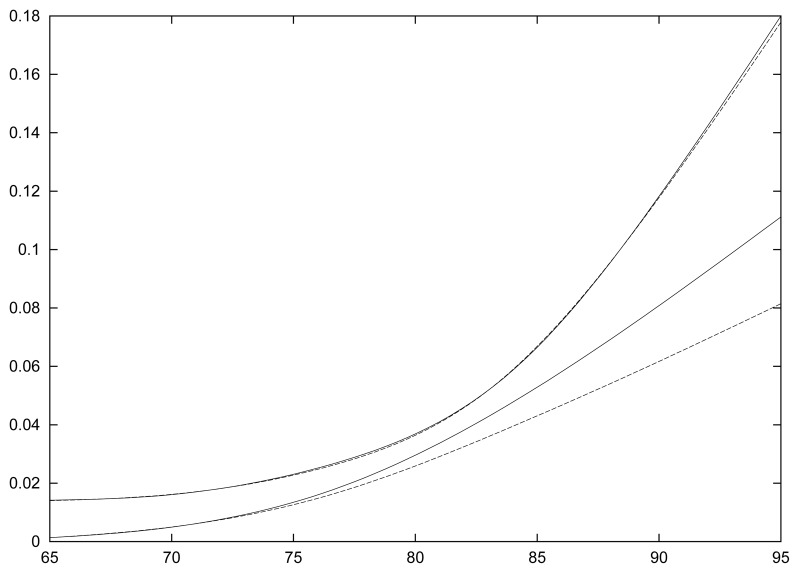

We have made an analysis including calendar time in the transition intensities according to a proportional intensity model as depicted in section 2.4., and also including educational level as a binary variable reflecting whether the subjects had obtained a primary school diploma, the “Certificat d’Etude Primaire” (CEP) (coded 1: without CEP; 0: with CEP). Table 1 shows the estimated coefficients together with their standard deviations for the three transitions and the two explanatory variables (the exponential of these coefficients yield estimated relative risks). Separate analyses have been made for women and men. We find as was already known [21] that subjects without CEP had a higher risk of developing dementia; the relative risk was about 2 for both men and women and was highly significant. There was no major effect of education on mortality rates except for demented men where a significant relative risk of 1.3 was observed. As for calendar time we observe strong effects on both incidence of dementia and mortality of demented, in both men and women: the estimated relative risk of developing dementia are 3.15 and 2.27 for 10 years for women and men respectively. We have made an additional analysis represented graphically on Figure 4. We have estimated on the global sample incidence of dementia and mortality rate for non-demented based on 8-year follow-up and on 10-year follow-up. While the estimates of the mortality rate are indistinguishable, the estimate of incidence based on the 10-year follow-up is clearly above that based on the 8-year follow-up. Thus in the Paquid data there is an increase of the incidence of dementia with calendar time. On the other hand mortality rates of demented decrease with calendar time: the relative risk is of the order of 2 for both men and women.

Table 1.

Proportional intensity illness-death model applied to the Paquid study: for each transition estimates of the regression coefficients with standard errors are given. Education is coded 1 if CEP, 0 otherwise; for calendar time the coefficient is given for a difference of ten years

| Transition | Education | Calendar time |

|---|---|---|

| Women | ||

|

| ||

| 0 → 1 | 0.70 (0.13) | 1.15 (0.20) |

| 1 → 2 | 0.09 (0.18) | −0.71 (0.30) |

| 0 → 2 | 0.08 (0.12) | 0.31 (0.18) |

|

| ||

| Men | ||

|

| ||

| 0 → 1 | 0.66 (0.19) | 0.82 (0.32) |

| 1 → 2 | −0.17 (0.24) | −0.75 (0.17) |

| 0 → 2 | 0.28 (0.11) | 0.18 (0.19) |

Figure 4.

Age-specific incidence of dementia and mortality rates for non-demented for the global sample based on 8-year and 10-year of follow–up. The two mortality rates are the upper curves and are indistinguishable; the lowest (dotted) line is the age-specific incidence based on the 8-year follow-up; the curve just above (continuous) is the age-specific incidence based on the 10-year follow-up.

6. Discussion

In this paper we have shown that the illness-death model was a good framework to model dementia, especially when the clinical statuses of subjects are observed at discrete visit times (which is in fact always the case). This is especially relevant when the focus is descriptive; the bias incurred in the relative risks estimators by treating the problem as a survival model should be low (although it has never been studied). We have given the likelihood and showed that the penalized likelihood allowed to obtain non-parametric estimators of the functions of interest, that is to say, age-specific incidence of dementia and mortality rates.

Our extended model allowed us to study the effect of calendar time on these transition intensities. The analysis was adjusted on educational level, an important risk factor that can vary with cohorts and thus could be a confounder for calendar time effect. Apo E status which is also an important risk factor was not included in the analysis for two reasons: i) it was available on only a small proportion of volonteers in the Paquid study; ii) its distribution at given age is not likely to change very much from one cohort to another and hence should not be a confounder for studying the effect of calendar time. We have found a surprisingly strong effect of calendar time on both age-specific incidence of dementia and mortality rate of demented subjects. This effect seems particularly strong between the 8-year and the 10-year follow-up, and this is more in favour of a calendar time effect than a cohort effect (which are statistically indistinguishable in a proportional intensity model, see section 2.4). This result could be due in part to an effect of non-missing at random data: demented subjects may have refused to be seen at previous visits and accept later provoking an apparent increase in the risk of dementia. The selection of the initial Paquid sample may explain a gradual apparent increase of the incidence: subjects were selected as living at home at the initial visit; since subjects living at home have probably a lower risk of developing dementia than subjects living in institution, this selection, not taken into account, may lead to a bias. The Markov assumption in our model also may lead to some bias: indeed it is likely that the mortality rates of demented subjects depend on the time since onset of the disease.

Among the several other explanations that have already been proposed in section 5, a shift in the application of the DSM-III-R criteria for dementia seems the most likely to have a strong effect. It is true that the perception of the disease has changed among both general practioners and neurologists. Twenty years ago Alzheimer’s disease was not really recognized as a disease in old subjects. There was first a progressive recognition of dementia as a disease and of the fact that most dementia was of Alzheimer type. This change has recently been accelerated by the appearance and the spread of cholinesterase inhibitors, the first effective drugs in this disease. It is tempting to give these drugs since the earliest stages of the disease and this leads to make the diagnosis earlier than before. This occurs even in an epidemiological study because the way the neurologists apply the DSM-III-R criteria for dementia has changed over time, in particular because there is no objective operational criterion to document that cognitive impairment significantly interferes with usual social activities or relationship with others. The decrease of the mortality rates of demented subjects is in agreement with this interpretation of the results, since if a subject is diagnosed for instance one year ealier than before he should live one more year in the demented state. This effect might also come from a genuine effect of the new drugs or other medical care.

More data and analyses are necessary to confirm these effects. If these effects are visible in the Paquid study, they may also be visible in other cohorts. If this was confirmed this would raise major methodological problems. One way of treating this problem would be to consider incidences depending on both age and calendar time, as we have done in this paper. For investigating the question of a possible increase of the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease with calendar time it would be safer to analyse criteria directly based on psychometrics tests and activity of daily living scores.

References

- 1.Peto R. Experimental survival curves for interval-censored data. Applied Statistics. 1973;22:86–91. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turnbull BW. The empirical distribution function with arbitrarily grouped, censored and truncated data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1976;38:290–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finkelstein D. A proportional hazards model for interval-censored failure time data. Biometrics. 1986;42:845–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alioum A, Commenges D. A proportional hazards model for arbitrarily censored and truncated data. Biometrics. 1996;52:95–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joly P, Commenges D, Letenneur L. A penalized likelihood approach for arbitrarily censored and truncated data: application to age-specific incidence of dementia. Biometrics. 1998;54:203–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Commenges D, Letenneur L, Joly P, Alioum A, Dartigues JF. Modelling age-specific risk: application to dementia. Statistics in Medicine. 1998;17:1973–1988. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980915)17:17<1973::aid-sim892>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersen PK. Multistate models in survival analysis: a study of nephropathy and mortality in diabetes. Statistics in Medicine. 1988;7:661–670. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780070605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keiding N. Age-specific incidence and prevalence: a statistical perspective. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A. 1991;154:371–412. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen PK, Borgan Ø, Gill RD, Keiding N. Statistical Models Based on Counting Processes. Springer-Verlag; New-York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Gruttola V, Lagakos SW. Analysis of doubly-censored survival data, with application to AIDS. Biometrics. 1989;45:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frydman H. A non-parametric estimation procedure for a periodically observed three-state Markov process, with application to AIDS. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1992;54:853–866. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frydman H. Semi-parametric estimation in a three-state duration-dependent Markov model from interval-censored observations with application to AIDS. Biometrics. 1995;51:502–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frydman H. Non-parametric estimation of a Markov “illness-death model” process from interval-censored observations, with application to diabetes survival data. Biometrika. 1995;82:773–789. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joly P, Commenges D. A penalized likelihood approach for a progressive three-state model with censored and truncated data: Application to AIDS. Biometrics. 1999;55:887–890. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joly P, Commenges D, Helmer C, Letenneur L. A penalized likelihood appproach for an illness-death model with interval-censored data: application to age-specific incidence of dementia. Biostatistics. 2002;3:433–443. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/3.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Commenges D. Multi-state models in epidemiology. Lifetime Data Analysis. 1999;5:315–327. doi: 10.1023/a:1009636125294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Commenges D. Inference for multistate models from interval-censored data. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2002;11:1–16. doi: 10.1191/0962280202sm279ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Commenges D. Research Report 02/5. Department of Biostatistics, University of Copenhagen; Denmark: 2002. Likelihood for interval-censored observations from multistate models. http://www.pubhealth.ku.dk/bsa/publ-e.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu C. Penalized likelihood hazard estimation: a general procedure. Statistica Sinica. 1996;6:861–876. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liquet B, Sakarovitch C, Commenges D. Bootstrap choice of estimators in non-parametric families: an extension of EIC. Biometrics. 2003;59:172–178. doi: 10.1111/1541-0420.00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letenneur L, Gilleron V, Commenges D, Helmer C, Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF. Are sex and educational level independent predictors of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease ? Incidence data from the PAQUID project. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1999;66:177–183. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helmer C, Joly P, Letenneur L, Commenges D, Dartigues JF. Mortality with dementia: results from a French prospective community-based cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;154:642–648. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.7.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]