Abstract

AIM

To analyze mortality associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in Italy.

METHODS

Death certificates mentioning either HBV or HCV infection were retrieved from the Italian National Cause of Death Register for the years 2011-2013. Mortality rates and proportional mortality (percentage of deaths with mention of HCV/HBV among all registered deaths) were computed by gender and age class. The geographical variability in HCV-related mortality rates was investigated by directly age-standardized rates (European standard population). Proportional mortality for HCV and HBV among subjects aged 20-59 years was assessed in the native population and in different immigrant groups.

RESULTS

HCV infection was mentioned in 1.6% (n = 27730) and HBV infection in 0.2% (n = 3838) of all deaths among subjects aged ≥ 20 years. Mortality rates associated with HCV infection increased exponentially with age in both genders, with a male to female ratio close to unity among the elderly; a further peak was observed in the 50-54 year age group especially among male subjects. HCV-related mortality rates were higher in Southern Italy among elderly people (45/100000 in subjects aged 60-79 and 125/100000 in subjects aged ≥ 80 years), and in North-Western Italy among middle-aged subjects (9/100000 in the 40-59 year age group). Proportional mortality was higher among Italian citizens and North African immigrants for HCV, and among Sub-Saharan African and Asian immigrants for HBV.

CONCLUSION

Population ageing, immigration, and new therapeutic approaches are shaping the epidemiology of virus-related chronic liver disease. In spite of limits due to the incomplete reporting and misclassification of the etiology of liver disease, mortality data represent an additional source of information for surveillance.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, Hepatitis B virus, Mortality, Epidemiology, Immigrants

Core tip: Multiple causes of death analyses carried out on the Italian National Cause of Death Register showed that 1.6% and 0.2% of all deaths in 2011-2013 were associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, respectively. HCV-associated mortality followed a bimodal distribution, increasing exponentially among the elderly in both genders, with a minor peak in middle-aged subjects, especially among males. The proportion of viral hepatitis-related deaths was higher among Italian citizens and North African immigrants for HCV, and among Sub-Saharan African and Asian immigrants for HBV.

INTRODUCTION

Viral hepatitis is one of the leading causes of death and disability worldwide, with a greater burden of disease associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in Europe, the Middle East, the Americas and North-Africa, and with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in sub-Saharan Africa and most of Asia[1].

Within Europe, Italy is affected by the highest prevalence of HCV infection, as well as by high rates of liver cancer mortality[2]. According to a recent systematic review, the prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies in other European countries ranges from 0.1% to 3.2%, whereas it has been estimated to be 5.9% in Italy[3]. HCV prevalence shows a steep increase with age in subjects born before 1950, and a marked geographical trend with higher rates in Southern compared to Northern regions[2].

The available data suggest unique features in the epidemiology of HCV infection in Italy with at least two different epidemic waves experienced during the past century. The first wave, which likely peaked in the 1950s and 1960s, mostly affected people born during the 1920s to 1930s and was probably associated with the widespread use of minor invasive procedures performed with improperly sterilized, non-disposable instruments. The second wave affected young adults in the 1970s and 1980s who suffered the largest impact of intravenous drug use-related HCV infections[4,5].

The vanishing effect of the first epidemic may have a profound impact on the burden of liver disease in Italy[5]: HCV infection might be considered mostly a feature of elderly subjects, and the mortality of HCV-related liver cancer is expected to decline in the years to come, which is line with the current observable trend[6].

The epidemiology of HBV has shown a progressive reduction in the endemicity levels with less than 1% of subjects in the overall population currently being HBsAg positive[7]. Similar to HCV, the burden of HBV infection could further decline given that the overall vaccination coverage rate is approximately 95% and nearly all Italian individuals under 35 years have now been vaccinated against HBV[7].

However, such favorable trends observed in more recent years could be impaired by the increasing number of immigrants living in Italy not vaccinated against HBV[7], and by a rising burden of HCV-associated disease with ageing of the cohort affected by the more recent HCV epidemic. In Italy, HBV and HCV testing has been so far carried out for high-risk or convenience groups (including intravenous drug users, blood donors, pregnant women, hospitalized patients), whereas there have not been national or regional testing strategies at the population level. Current population-based epidemiological figures on virus-related chronic liver disease in Italy are based mainly on local studies, whereas nationwide data are lacking. The aim of this study was to assess the burden and variability of mortality associated with HBV and HCV infection by analyzing the data obtained by the national database of causes of death.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All analyses were carried out on the Italian National Cause of Death Register, managed by the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). Data are based on the information reported on death certificates; all the diseases mentioned in the certificate are coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10 2009 version). Standard mortality statistics are usually based on internationally adopted algorithms that identify a single underlying cause of death (UCOD) from all the conditions reported in the certificate. Analyses based on any mention of a disease irrespective of its selection as the UCOD, the so-called multiple causes of death approach (MCOD), can more fully describe the burden of mortality associated with chronic diseases[8].

All deaths from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2013 of subjects resident in Italy and aged ≥ 20 years with any mention in the death certificate of HCV (ICD-10 codes B17.1, B18.2) or HBV infection (ICD-10 B16.0-B16.9, B17.0, B18.0, B18.1) were extracted. Age and gender-specific mortality rates were computed for the whole nation as well as by area of residence (North-West, North-East, Centre, South, Islands). The geographical variability in HCV-related mortality rates was summarized by directly age-standardized rates (European standard population) both for the whole population aged ≥ 20 years, and for broad age classes. Proportional mortality was defined as the percentage of deaths with any mention of HCV or HBV out of all registered deaths, and was computed by age, gender, and immigrant status based on the country of citizenship. To deal with larger numbers, non-Italian countries of citizenship were grouped by area of provenance on the basis of macro-geographical regions and sub-regions: North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia (Indian subcontinent), other Asian countries, Central and South America, EU15 and other developed countries. Furthermore, analyses were restricted to the 20-59-year age band, where the immigrant population is more represented[9]. Among deaths with mention of HCV or HBV infection, the selected UCOD was analyzed by age class according to broad nosological sectors: viral hepatitis, liver cancer, and chronic liver diseases (ICD-10 B15-B19, C22, K70, K73, K74), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS, B20-B24), neoplasms other than liver cancer (C00-D48, except for C22), circulatory diseases (I00-I99), and a residual category including all other diseases.

RESULTS

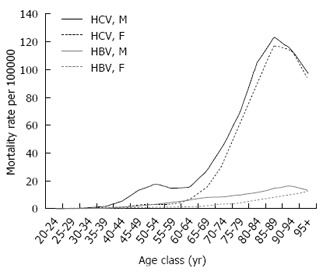

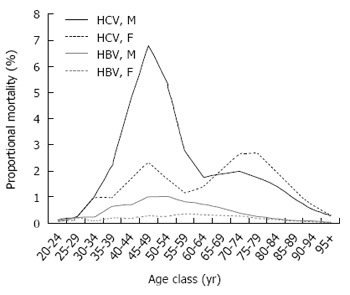

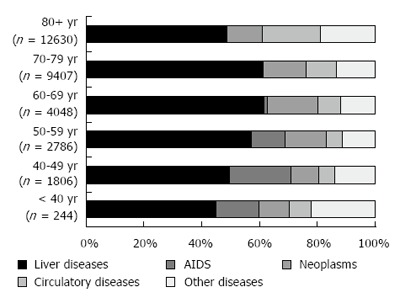

Out of 1787434 deaths of subjects aged ≥ 20 years in the causes of death registry, HCV infection was mentioned in 1.6% (n = 27730) and HBV infection in 0.2% (n = 3838). These two groups included 647 decedents presenting with HBV-HCV co-infection. Figure 1 shows that the mortality rate associated with HCV infection increased exponentially with age in both genders, and among the elderly, the male to female ratio was close to unity. A further peak was observed in the 50-54-year age-group, especially among males, with a male to female ratio equal to 5.3. Mortality rates associated with HBV infection increased slowly with age and were always higher in the male gender. Proportional mortality figures (Figure 2) confirmed the bimodal distribution of HCV-related deaths. The selected UCOD was a liver disease (cirrhosis, liver cancer, viral hepatitis) in the majority of deaths with mention of HCV or HBV infection. This was observed especially in subjects aged 50-79 years (Figure 3). Among younger decedents a large proportion was represented by AIDS, whereas among the very elderly the UCOD was more evenly distributed across different nosological sectors.

Figure 1.

Mortality associated with hepatitis C virus and hepatitis B virus infection: Age and gender-specific mortality rates, Italy 2011-2013. HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

Figure 2.

Mortality associated with hepatitis C virus and hepatitis B virus infection: Age and gender-specific proportional mortality, Italy 2011-2013. HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the underlying cause of death among decedents with mention of hepatitis C or hepatitis B infection, by age class, Italy, 2011-2013.

The overall age-standardized HCV-related mortality rate was higher in Southern Italy (Table 1). However, the findings were observed to vary depending on the age class. The peak in mortality among people aged ≥ 60 years was higher in Southern Italy, whereas mortality rates in the 40-59-year age band, corresponding to the lower peak registered among middle-aged subjects, was more pronounced in the North-Western and Central regions of the country.

Table 1.

Mortality associated with hepatitis C virus infection across Italian areas: age-standardized mortality rates per 100000 (European standard population), 2011-2013

| Italy | North-West | North-East | Centre | South | Islands | |

| 20-39 yr | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| 40-59 yr | 7.7 | 9.1 | 6.8 | 8.7 | 6.5 | 6.7 |

| 60-79 yr | 30.9 | 31.1 | 22.8 | 21.9 | 45.0 | 34.5 |

| 80+ yr | 106.1 | 120.3 | 99.9 | 80.1 | 125 | 95.2 |

| All ages 20+ | 17.7 | 19.1 | 14.8 | 14.0 | 22.1 | 17.6 |

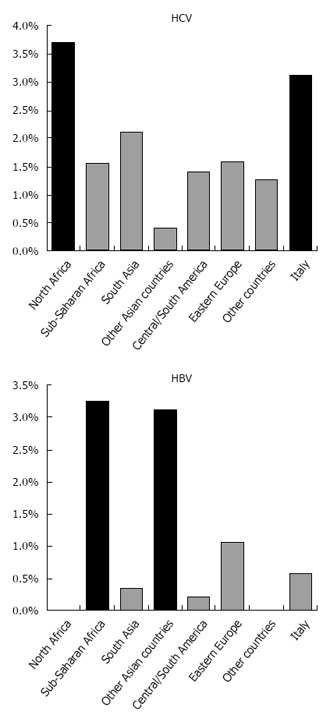

In analyses restricted to the 20-59-year band, HCV infection was mentioned in 4092 Italian and 120 immigrant decedents, and HBV infection in 757 Italian and 78 immigrant decedents; information on citizenship was missing for 8 and 6 subjects with HCV and HBV infection, respectively. In spite of low numbers among immigrants, Figure 4 shows that proportional mortality for HCV infection was higher among Italian citizens and immigrants from North Africa. In the case of HBV infection, the proportional mortality was higher among immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa and Asian countries.

Figure 4.

Mortality associated with hepatitis C virus and hepatitis B virus infection by country of citizenship: Proportional mortality among decedents aged 20-59 years, Italy 2011-2013. HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

DISCUSSION

Analyses of death certificates are known to be affected by incomplete reporting and misclassification of the etiology of liver diseases, leading to an underestimation of the true mortality burden associated with chronic viral infection[10]. The physicians filling in death certificates may be unaware of HCV or HBV infection in the patient or may not consider that the disease contributed to the death. Furthermore, among elderly patients affected by multiple comorbidities, there may be no simple etiologic chain leading to the identification of a single underlying cause; especially in the contest of ageing populations like in Italy, death often results from a complex interaction between multiple factors. As a consequence, instead of relying only on the underlying cause of death, the MCOD approach allows a more complete identification of the burden of mortality attributable to viral hepatitis infection. The MCOD methodology has been applied in the United States to monitor time trends in HCV-related mortality[10,11], and to assess the burden of HCV-related deaths in high-risk populations such as prison inmates[12]. In Italy, MCOD analyses of virus-related liver diseases have been carried out only at the regional level[13]. This first nationwide report allows for the investigation of variations in mortality by age, gender, area of residence, and immigrant status, thereby providing a raw but comprehensive picture of the contemporary burden of HCV and HBV-related mortality in Italy.

Repeated surveys carried out in a small town in Southern Italy suggest a decreasing prevalence of HCV infection, being mostly confined to the oldest age groups[14]. Moreover, clinical studies found that, although HCV infection still represents the main etiology for chronic liver disease in Italy, its role is declining in more recent years[15,16]. The present data suggest that the current burden of HCV-related disease among elderly Italians is still large, especially in Southern regions. These figures must be interpreted within the frame of the recent availability of safe and effective drugs that will change the approach to the aged HCV patient, with an increasing number of treatment candidates[17]. Furthermore, mortality data confirm the presence of two distinct epidemic waves that have partly been associated with different HCV subtypes[18]. A bimodal distribution of HCV infection has been previously reported by seroprevalence surveys conducted both in Northern[19] as well as in Southern Italy[20], and by analyses of the mention of HCV infection in records from a sample of Italian general practitioners[21]. The peak in middle-aged subjects is most likely associated with intravenous drug abuse as well as with other risk factors (including tattoos and piercing) typical of younger generations[19]. Such a peak is well-recognizable from mortality rates at least in the male gender, and must strictly be monitored in the future: HCV-related liver disease progresses faster with aging, extra-hepatic manifestations of HCV infection are probably worse in the elderly, and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma increases with age[17]. In the United States, where HCV infection is mostly restricted to the 1945-1965 birth cohort, HCV-related mortality assessed with the MCOD methodology is steeply increasing[10]. The HCV-related mortality wave is rapidly rising in the United States as the age of the affected birth cohort is increasing[22]; a similar unfavorable trend could be observed in Italy in the near future. Furthermore, mortality data suggest that the geographical variation in the burden of HCV differs across age groups, with higher rates observed among middle-aged subjects residing in Northern and Central Italy with respect to the Southern regions.

Mortality among immigrants mirrors the available data on the global epidemiology of viral hepatitis. Estimates for the prevalence of HCV infection range from < 1.0% in Northern Europe to > 2.9% in Northern Africa, with the highest prevalence (15%-20%) reported from Egypt[23]. Similar to Italy, other countries with high HCV prevalence suffered from iatrogenic spread around the middle of the past century. In Egypt, this was due to parenteral antischistosomal therapy through 1961-1986[24]; mass trypanosomiasis therapy before 1951 in the Central Africa Republic, and intravenous treatment with antimalarial drugs and other medical interventions in Cameroon, also caused iatrogenic transmission of HCV[25]. Data on HBV-related mortality are consistent with the rates that have been reported from the countries of origin and with previous studies on immigrants in Italy. Among undocumented immigrants in a city in Northern Italy, 6% tested positive for HBsAg; the only independent predictor was the prevalence of HBV infection in the area of provenance, with higher rates for subjects from Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia[26]. The present mortality analysis was carried out on legal residents with foreign citizenship, representing about 5000000 subjects (8.3% of all residents in Italy, 10.9% in the 20-59-year age band), and was not restricted to selected high-risk groups like undocumented immigrants or asylum seekers. All of the above evidence should guide a re-appraisal of strategies tailored according to the area of provenance for screening, HBV vaccination, HBV and HCV infection treatment of the immigrant population.

In conclusion, population ageing, an increase in the number of immigrants from countries with high HBV and HCV prevalence, and changes in the therapeutic approaches are re-shaping the epidemiology of virus-related chronic liver disease. MCOD data are a useful tool among the multiple information sources needed to monitor this rapidly evolving scenario.

COMMENTS

Background

Within Europe, Italy is affected by the highest prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. HCV prevalence shows a steep increase with age in subjects born before 1950, and a marked geographical trend with higher rates in Southern compared to Northern regions.

Research frontiers

Population-based epidemiological figures on virus-related chronic liver disease in Italy are based mainly on local studies. Mortality records can provide a nationwide estimate of the impact of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HCV infection.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Mortality rates associated with HCV infection increased exponentially with age in both genders. A further peak was observed in the 50-54-year age class, especially among males. HCV-related mortality rates were higher in Southern Italy among elderly subjects, and in North-Western Italy among middle-aged subjects.

Applications

Despite the limit of incomplete reporting of the etiology of liver disease, the analysis of mortality data represents an additional tool for investigating the impact of HBV and HCV infection.

Terminology

Multiple causes of death approach: the analysis of mortality records based not only on the selected underlying cause of death, but on any mention of a disease in the death certificate.

Peer-review

As the authors acknowledge, death certificates provide incomplete or misclassified health condition data. Hence, their data likely underestimates HBV and HCV prevalence. Despite these limitations, the study provides data not currently available in the literature which is immediately useful for clinicians and public health authorities to follow trends in HBV and HCV disease-related mortality.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: Mortality data are routinely collected by the National Institute of Statistics. All analyses were carried out on aggregated data without any possibility of identification of individuals; therefore, the study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Informed consent statement: Since analyses were carried out on retrospective, routinely collected aggregated data, the informed consent was not required.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: November 16, 2016

First decision: December 28, 2016

Article in press: February 17, 2017

P- Reviewer: Hunt CM, Makara M, Morikawa K S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C, Vos T, Abubakar I, Abu-Raddad LJ, Assadi R, Bhala N, Cowie B, et al. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016;388:1081–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30579-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Hepatitis B and C in the EU neighbourhood: prevalence, burden of disease and screening policies. Stockholm: ECDC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Systematic review on hepatitis B and C prevalence in the EU/EEA. Stockholm: ECDC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mariano A, Scalia Tomba G, Tosti ME, Spada E, Mele A. Estimating the incidence, prevalence and clinical burden of hepatitis C over time in Italy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2009;41:689–699. doi: 10.1080/00365540903095358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puoti M, Girardi E. Chronic hepatitis C in Italy: the vanishing of the first and most consistent epidemic wave. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:369–370. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cazzagon N, Trevisani F, Maddalo G, Giacomin A, Vanin V, Pozzan C, Poggio PD, Rapaccini G, Nolfo AM, Benvegnù L, et al. Rise and fall of HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma in Italy: a long-term survey from the ITA.LI.CA centres. Liver Int. 2013;33:1420–1427. doi: 10.1111/liv.12208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sagnelli E, Sagnelli C, Pisaturo M, Macera M, Coppola N. Epidemiology of acute and chronic hepatitis B and delta over the last 5 decades in Italy. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7635–7643. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frova L, Salvatore MA, Pappagallo M, Egidi V. Multiple cause of death approach to analyze mortality patterns. Genus. 2009;65:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fedeli U, Ferroni E, Pigato M, Avossa F, Saugo M. Causes of mortality across different immigrant groups in Northeastern Italy. PeerJ. 2015;3:e975. doi: 10.7717/peerj.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ly KN, Hughes EM, Jiles RB, Holmberg SD. Rising Mortality Associated With Hepatitis C Virus in the United States, 2003-2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:1287–1288. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, Jiles RB, Ward JW, Holmberg SD. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:271–278. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harzke AJ, Baillargeon JG, Kelley MF, Diamond PM, Goodman KJ, Paar DP. HCV-related mortality among male prison inmates in Texas, 1994-2003. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:582–589. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fedeli U, Avossa F, Goldoni CA, Caranci N, Zambon F, Saugo M. Education level and chronic liver disease by aetiology: A proportional mortality study. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:1082–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.07.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guadagnino V, Stroffolini T, Caroleo B, Menniti Ippolito F, Rapicetta M, Ciccaglione AR, Chionne P, Madonna E, Costantino A, De Sarro G, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in an endemic area of Southern Italy 14 years later: evidence for a vanishing infection. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:403–407. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroffolini T, Sagnelli E, Gaeta GB, Sagnelli C, Andriulli A, Brancaccio G, Pirisi M, Colloredo G, Morisco F, Furlan C, et al. Characteristics of liver cirrhosis in Italy: Evidence for a decreasing role of HCV aetiology. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;38:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saracco GM, Evangelista A, Fagoonee S, Ciccone G, Bugianesi E, Caviglia GP, Abate ML, Rizzetto M, Pellicano R, Smedile A. Etiology of chronic liver diseases in the Northwest of Italy, 1998 through 2014. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8187–8193. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i36.8187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, Galati G, Gallo P, De Vincentis A, Riva E, Picardi A. Hepatitis C treatment in the elderly: New possibilities and controversies towards interferon-free regimens. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7412–7426. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i24.7412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ansaldi F, Bruzzone B, Salmaso S, Rota MC, Durando P, Gasparini R, Icardi G. Different seroprevalence and molecular epidemiology patterns of hepatitis C virus infection in Italy. J Med Virol. 2005;76:327–332. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fabris P, Baldo V, Baldovin T, Bellotto E, Rassu M, Trivello R, Tramarin A, Tositti G, Floreani A. Changing epidemiology of HCV and HBV infections in Northern Italy: a survey in the general population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:527–532. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318030e3ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polilli E, Tontodonati M, Flacco ME, Ursini T, Striani P, Di Giammartino D, Paoloni M, Vallarola L, Pressanti GL, Fragassi G, et al. High seroprevalence of HCV in the Abruzzo Region, Italy: results on a large sample from opt-out pre-surgical screening. Infection. 2016;44:85–91. doi: 10.1007/s15010-015-0841-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lapi F, Capogrosso Sansone A, Mantarro S, Simonetti M, Tuccori M, Blandizzi C, Rossi A, Corti G, Bartoloni A, Bellia A, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection: opportunities for an earlier detection in primary care. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:271–276. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fedeli U, Schievano E. Mortality Waves Related to Hepatitis C Virus Infection: Multiple Causes of Death Data From the United States and Northern Italy Compared. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:849–850. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2436–2441. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank C, Mohamed MK, Strickland GT, Lavanchy D, Arthur RR, Magder LS, El Khoby T, Abdel-Wahab Y, Aly Ohn ES, Anwar W, et al. The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Lancet. 2000;355:887–891. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)06527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strickland GT. An epidemic of hepatitis C virus infection while treating endemic infectious diseases in Equatorial Africa more than a half century ago: did it also jump-start the AIDS pandemic? Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:785–787. doi: 10.1086/656234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Hamad I, Pezzoli MC, Chiari E, Scarcella C, Vassallo F, Puoti M, Ciccaglione A, Ciccozzi M, Scalzini A, Castelli F. Point-of-care screening, prevalence, and risk factors for hepatitis B infection among 3,728 mainly undocumented migrants from non-EU countries in northern Italy. J Travel Med. 2015;22:78–86. doi: 10.1111/jtm.12176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]