Abstract

AIM

To evaluate the prognostic value of site-specific metastases among patients with metastatic pancreatic carcinoma registered within the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database.

METHODS

SEER database (2010-2013) has been queried through SEER*Stat program to determine the presentation, treatment outcomes and prognostic outcomes of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma according to the site of metastasis. In this study, metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients were classified according to the site of metastases (liver, lung, bone, brain and distant lymph nodes). We utilized chi-square test to compare the clinicopathological characteristics among different sites of metastases. We used Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank testing for survival comparisons. We employed Cox proportional model to perform multivariate analyses of the patient population; and accordingly hazard ratios with corresponding 95%CI were generated. Statistical significance was considered if a two-tailed P value < 0.05 was achieved.

RESULTS

A total of 13233 patients with stage IV pancreatic cancer and known sites of distant metastases were identified in the period from 2010-2013 and they were included into the current analysis. Patients with isolated distant nodal involvement or lung metastases have better overall and pancreatic cancer-specific survival compared to patients with isolated liver metastases (for overall survival: lung vs liver metastases: P < 0.0001; distant nodal vs liver metastases: P < 0.0001) (for pancreatic cancer-specific survival: lung vs liver metastases: P < 0.0001; distant nodal vs liver metastases: P < 0.0001). Multivariate analysis revealed that age < 65 years, white race, being married, female gender; surgery to the primary tumor and surgery to the metastatic disease were associated with better overall survival and pancreatic cancer-specific survival.

CONCLUSION

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients with isolated liver metastases have worse outcomes compared to patients with isolated lung or distant nodal metastases. Further research is needed to identify the highly selected subset of patients who may benefit from local treatment of the primary tumor and/or metastatic disease.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, Liver metastases, Lung metastases, Bone metastases, Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database

Core tip: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients with isolated liver metastases have worse outcomes compared to patients with isolated lung or distant nodal metastases. Further research is needed to identify the highly selected subset of patients who may benefit from local treatment of the primary tumor and/or metastatic disease.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer is a global health burden with a poor prognosis and a difficult to treat biology in the majority of cases[1]. Histologically, pancreatic adenocarcinoma represents the majority of pancreatic cancer cases; and unfortunately the worst prognosis[2].

Treatment decisions for pancreatic adenocarcinoma differ according to patient- and disease-related factors. For fit patients with localized disease, surgical resection should always be considered, to be followed by or preceded by systemic chemotherapy[3]; while for locally advanced disease, personalized multimodality treatment strategies may be proposed[4]. For patients with metastatic disease, the primary treatment is systemic therapy (which may include systemic chemotherapy and more recently targeted therapy)[5].

Unfortunately, population-based studies in many parts of the world have shown a limited improvement in survival for non metastatic pancreatic cancer patients over years[6]. The situation is even worse for advanced stages of the disease[7]; and this calls for reconsideration of the current therapeutic strategies for this disease.

In the setting of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma, liver is the most common site of metastasis. However, some cases may experience a change of the metastatic pattern and involve other distant organs without involving the liver. These cases may represent a different subset of patients with different biology and prognosis and subsequently different therapeutic approach[8-10].

Population-based data on the prognostic value of site-specific metastases for pancreatic adenocarcinoma are lacking. And thus, the objective of this study is to review the presentation and treatment trends of metastatic pancreatic cancer patients registered within the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database with a particular focus on the prognostic value of different sites of metastases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was based on the publicly available SEER-18 registry of the United States national cancer institute[11]. We retrieved data using the SEER*Stat software Version 8.3.2. Because this study is based on a publicly available database, it was exempted from IRB approval.

Data collection

We restricted our search to SEER database (2010-2013) because detailed information about the site of distant metastases was not available before 2010.

To identify metastatic pancreatic cancer patients, we included cases with a primary site of “pancreas”, with ICD-O-Histology/behavior codes of 8140/3, 8141/3, 8142/3, 8143/3, 8144/3 and 8145/3 (variants of adenocarcinoma) and with AJCC stage IV. We excluded patients without sufficient survival data or data about the site of the metastases.

Data extracted for each case included age at diagnosis, gender, race, marital status, T stage, N stage, site of metastases, surgery to the primary and metastases, cause-specific death classification, survival months and vital status. For the sake of the current analysis, pancreatic cancer-specific survival was defined as time from diagnosis to death from pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Data about systemic therapy were not available in the SEER database.

Statistical analysis

In this study, metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients were classified according to the site of metastases (liver, lung, bone, brain and distant lymph nodes). We utilized chi-square test to compare the clinicopathological characteristics among different sites of metastases. We used Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank testing for survival comparisons.

We employed Cox proportional model to perform multivariate analyses of the patient population; and accordingly hazard ratios with corresponding 95%CI were generated. Statistical significance was considered if a two-tailed P value < 0.05 was achieved. All of the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM, NY, United States).

RESULTS

Patients' characteristics

A total of 13233 patients with stage IV pancreatic cancer at the time of initial diagnosis and known sites of distant metastases were identified in the period from 2010-2013 and they were included into the current study. Table 1 summarizes the distribution of different metastatic sites for all included patients. 10088 (76%) patients were diagnosed with liver metastases, 2638 (19.9%) patients were diagnosed with lung metastases, and 910 (6.8%) patients were diagnosed with bone metastases, 90 (0.6%) patients were diagnosed with brain metastases, 1246 (9.4%) patients were diagnosed with distant (non regional) lymph nodes. 8786 (66.3%) patients have a single organ site of metastases while 4447 patients (33.7%) patients have multi-organ metastases. Statistically significant correlations between different baseline characteristics and different sites of metastases are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical features and metastatic sites n (%)

| Features |

Bone metastases |

P value |

Liver metastases |

P value |

Lung metastases |

P value |

Distant lymph nodes |

P value |

Brain metastases |

P value | |||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||||

| Age (yr) | 0.002 | < 0.0001 | 0.008 | < 0.0001 | 0.636 | ||||||||||

| < 65 | 396 (7.7) | 4724 (92.3) | 3996 (78.0) | 1124 (22.0) | 961 (18.8) | 4159 (81.2) | 569 (11.1) | 4551 (88.9) | 37 (0.7) | 5083 (99.3) | |||||

| ≥ 65 | 514 (6.3) | 7599 (93.7) | 6092 (75.1) | 2021 (24.9) | 1677 (20.7) | 6463 (79.3) | 677 (8.3) | 7436 (91.7) | 53 (0.7) | 8060 (99.3) | |||||

| Race | 0.076 | 0.001 | 0.312 | 0.059 | 0.314 | ||||||||||

| White | 727 (9.6) | 9734 (93.1) | 7974 (76.2) | 2487 (23.8) | 2106 (20.1) | 8355 (79.9) | 1005 (9.6) | 9456 (90.4) | 71 (0.7) | 10390 (99.3) | |||||

| Black | 105 (5.9) | 1661 (94.1) | 1388 (78.6) | 378 (21.4) | 329 (18.6) | 1437 (81.4) | 140 (7.9) | 1626 (92.1) | 16 (0.9) | 1750 (99.1) | |||||

| Others | 928 (93) | 78 (7.0) | 726 (73.0) | 280 (27.0) | 203 (19.0) | 803 (81.0) | 905 (90.0) | 101 (10.0) | 3 (0.2) | 1003 (99.8) | |||||

| Gender | 0.002 | < 0.0001 | 0.020 | 0.028 | 0.770 | ||||||||||

| Male | 636 (7.5) | 6613 (92.5) | 5565 (77.8) | 1584 (22.2) | 1372 (19.2) | 5777 (80.8) | 710 (9.9) | 6439 (90.1) | 50 (0.7) | 7099 (99.3) | |||||

| Female | 374 (6.1) | 5710 (93.9) | 4523 (74.3) | 1561 (25.7) | 1266 (20.8) | 4818 (79.2) | 536 (8.8) | 5548 (91.2) | 40 (0.7) | 6044 (99.3) | |||||

| Location of the primary | 0.001 | 0.084 | < 0.0001 | 0.003 | 0.024 | ||||||||||

| Head | 269 (5.8) | 4387 (94.2) | 3580 (76.9) | 1076 (23.1) | 828 (17.2) | 3828 (82.2) | 480 (10.3) | 4176 (89.7) | 21 (0.5) | 4635 (99.5) | |||||

| Body/tail | 340 (7.2) | 4408 (92.8) | 3638 (76.6) | 1110 (23.4) | 961 (20.2) | 3787 (79.8) | 394 (8.3) | 4354 (91.7) | 33 (0.7) | 4715 (99.3) | |||||

| Unknown | 301 (7.9) | 3528 (92.1) | 2870 (75.0) | 959 (25.0) | 849 (22.2) | 2980 (77.8) | 372 (9.7) | 3457 (90.3) | 36 (0.9) | 3793 (99.1) | |||||

| Marital status | 0.083 | 0.895 | 0.083 | 0.014 | 0.189 | ||||||||||

| Married | 512 (7.1) | 6720 (92.9) | 5510 (76.2) | 1722 (23.8) | 1402 (19.4) | 5830 (80.6) | 722 (10.0) | 6510 (90.0) | 43 (0.6) | 7189 (99.4) | |||||

| Unmarried | 398 (6.6) | 5603 (93.4) | 4578 (76.3) | 1423 (23.7) | 1236 (20.6) | 4765 (79.4) | 524 (8.7) | 5477 (91.3) | 47 (0.8) | 5954 (99.2) | |||||

| T stage | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.003 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||

| T1 | 29 (8.9) | 296 (91.1) | 242 (74.5) | 83 (25.5) | 59 (18.2) | 266 (81.8) | 23 (7.1) | 302 (92.9) | 3 (0.9) | 322 (99.1) | |||||

| T2 | 209 (6.7) | 3079 (93.6) | 2705 (82.3) | 583 (17.7) | 595 (18.1) | 2693 (81.9) | 277 (8.4) | 3011 (91.6) | 17 (0.5) | 3271 (99.5) | |||||

| T3 | 200 (5.5) | 3460 (94.5) | 2699 (73.7) | 961 (26.3) | 711 (19.4) | 2949 (80.6) | 345 (9.4) | 3315 (90.6) | 11 (0.3) | 3649 (99.7) | |||||

| T4 | 153 (6.8) | 2106 (93.2) | 1611 (71.3) | 648 (28.7) | 504 (22.3) | 1755 (77.7) | 278 (12.3) | 1981 (87.7) | 13 (0.6) | 2246 (99.4) | |||||

| Tx | 319 (9.0) | 3382 (91.0) | 2831 (76.0) | 870 (24.0) | 769 (20.5) | 2932 (79.5) | 323 (10.0) | 3378 (90.0) | 46 (1.2) | 3655 (98.8) | |||||

| N stage | < 0.0001 | 0.788 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.089 | ||||||||||

| N0 | 395 (5.8) | 6424 (94.2) | 5210 (76.4) | 1609 (23.6) | 1143 (16.8) | 5676 (83.2) | 310 (4.5) | 6509 (95.5) | 36 (0.5) | 6783 (99.5) | |||||

| N1 | 354 (8.7) | 3729 (91.3) | 3097 (75.9) | 986 (24.1) | 1018 (24.9) | 3065 (75.1) | 811 (19.9) | 3272 (80.1) | 34 (0.8) | 4049 (99.2) | |||||

| Nx | 161 (6.9) | 2170 (93.1) | 1781 (76.4) | 550 (23.6) | 477 (20.5) | 1854 (79.5) | 125 (5.4) | 2206 (94.5) | 20 (0.9) | 2311 (99.1) | |||||

| Surgery of the primary | 0.035 | < 0.0001 | 0.006 | 0.265 | 0.422 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 7 (3.1) | 218 (96.9) | 112 (49.8) | 113 (50.2) | 26 (11.6) | 199 (88.4) | 15 (6.7) | 210 (93.3) | 0 (0) | 225 (100.0) | |||||

| No | 903 (7.0) | 12105 (93.0) | 9976 (76.7) | 3033 (23.3) | 2612 (20.1) | 10369 (79.9) | 1231 (9.5) | 11777 (90.5) | 90 (0.7) | 12918 (99.3) | |||||

| Surgery of the metastases | 0.808 | < 0.0001 | 0.002 | < 0.0001 | 0.503 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 38 (6.6) | 534 (93.4) | 288 (50.3) | 284 (49.7) | 81 (14.2) | 491 (85.8) | 91 (15.9) | 481 (84.1) | 6 (1.0) | 566 (99.0) | |||||

| No | 872 (6.7) | 11789 (93.3) | 9800 (77.4) | 2861 (22.6) | 2557 (20.2) | 10104 (79.8) | 1155 (9.1) | 11506 (90.9) | 84 (0.7) | 12577 (99.3) | |||||

Surgical resection of the primary tumor was performed in 225 (1.7%) patients while surgical resection of the metastatic lesions was performed in 572 (4.3%). No information was provided in the SEER database about systemic treatment.

Survival outcomes

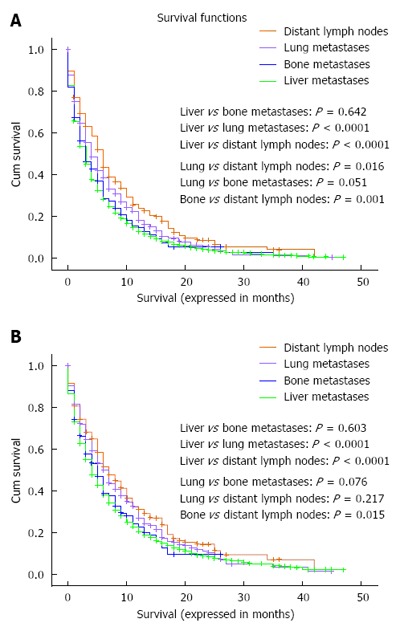

Overall and pancreatic cancer-specific survival were compared according to the site of metastases; for both endpoints, patients with isolated distant lymph node involvement or lung metastases have better outcomes compared to patients with isolated liver metastases (for overall survival: lung vs liver metastases: P < 0.0001; distant nodal vs liver metastases: P < 0.0001; lung vs bone metastases: P = 0.051; distant nodal vs bone metastases: P = 0.001) (for pancreatic cancer-specific survival: lung vs liver metastases: P < 0.0001; distant nodal vs liver metastases: P < 0.0001; lung vs bone metastases: P = 0.076; distant nodal vs bone metastases: P = 0.015) (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve of: overall survival (A), and pancreatic cancer-specific survival (B) according to the site of single site metastases.

Moreover, patients with isolated distant lymph node involvement but not those with lung metastases have better outcomes compared to patients with isolated bone metastases (for overall survival: lung vs bone metastases: P = 0.051; distant nodal vs bone metastases: P = 0.001) (for pancreatic cancer-specific survival: lung vs bone metastases: P = 0.076; distant nodal vs bone metastases: P = 0.015) (Figure 1A and B). Because of the very small number of patients with brain metastases (90 patients), they were not included in this analysis.

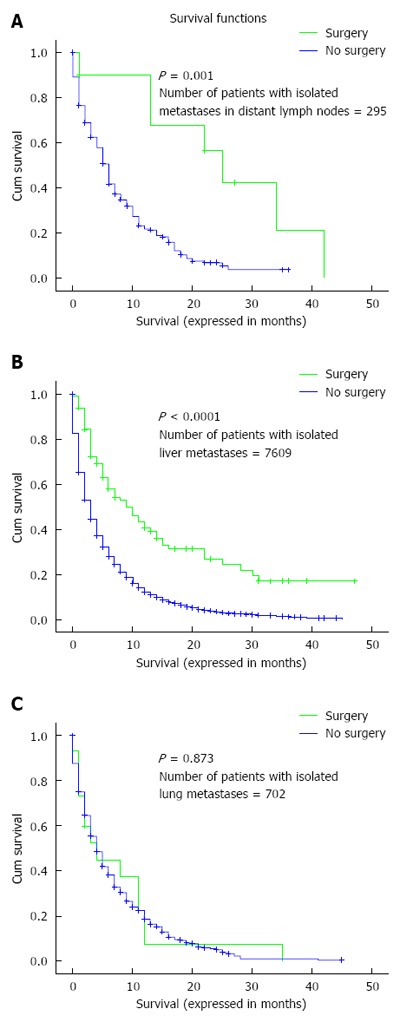

Overall survival was assessed according to whether or not surgery to the primary tumor was performed in patients with isolated liver, lung and distant nodal metastases. There was evidence of benefit for patients with isolated liver or distant nodal metastases but not for patients with isolated lung metastases (Figure 2A-C).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of overall survival according to whether or not surgery to the primary has been done: (A) patients with isolated distant nodal deposits; (B) patients with isolated liver metastases; (C) patients with isolated lung metastases.

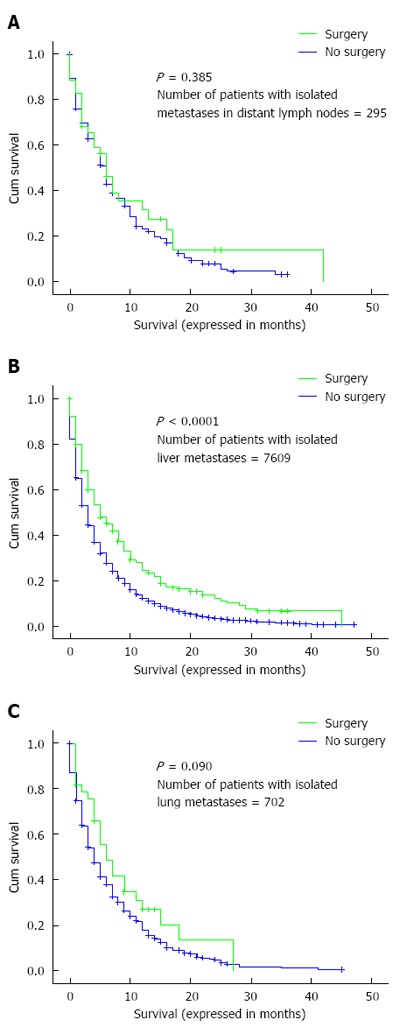

Overall survival was also evaluated according to whether or not surgery to the metastatic disease was performed in patients with isolated liver, lung or distant nodal metastases. There was evidence of benefit for patients with isolated liver metastases but not for patients with isolated lung or distant nodal metastases (Figure 3A-C).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve of overall survival according to whether or not surgery to the metastatic disease has been done: (A) patients with isolated distant nodal deposits; (B) patients with isolated liver metastases; (C) patients with isolated lung metastases.

Multivariate analysis revealed that age < 65 years, white race, being married, female gender; surgery to the primary tumor and surgery to the metastatic disease were associated with better overall survival and pancreatic cancer-specific survival (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate analyses of overall survival and pancreatic cancer-specific survival in metastatic pancreatic cancer patients

| Features |

Overall survival |

Pancreatic cancer-specific survival |

||

| Hazard ratio(95%CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | ||||

| < 65 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| > 65 | 1.343 (1.292-1.396) | < 0.0001 | 1.131 (1.083-1.181) | < 0.0001 |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| White | 0.913 (0.865-0.965) | 0.001 | 0.924 (0.869-0.983) | 0.013 |

| Others | 0.891 (0.818-0.971) | 0.009 | 0.956 (0.870-1.052) | 0.360 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Male | 1.117 (1.075-1.160) | < 0.0001 | 1.087 (1.042-1.135) | < 0.0001 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Unmarried | 1.243 (1.196-1.291) | < 0.0001 | 1.222 (1.170-1.276) | < 0.0001 |

| T stage | ||||

| T1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| T2 | 1.151 (1.015-1.304) | 0.028 | 1.170 (1.015-1.349) | 0.030 |

| T3 | 1.014 (0.895-1.149) | 0.826 | 1.033 (0.896-1.191) | 0.652 |

| T4 | 0.974 (0.857-1.107) | 0.688 | 0.986 (0.853-1.141) | 0.851 |

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| N1 | 1.004 (0.962-1.049) | 0.841 | 1.001 (0.954-1.051) | 0.958 |

| Surgery of the primary | ||||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Yes | 0.573 (0.489-0.671) | < 0.0001 | 0.537 (0.448-0.643) | < 0.0001 |

| Surgery of the metastases | ||||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Yes | 0.773 (0.703-0.851) | < 0.0001 | 0.782 (0.703-0.871) | < 0.0001 |

| Distant metastases | ||||

| Multiple metastases | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Single metastasis | 1.080 (0.900-1.297) | 0.409 | 1.049 (0.867-1.270) | 0.619 |

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study are: (1) patients with distant nodal and lung metastases from pancreatic adenocarcinoma have a statistically significant better prognosis than patients with liver metastases; and (2) surgical resection could play a role in the management of a highly selected subset of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and isolated resectable liver or distant nodal metastases.

Knowledge of the prognostic consequences of having one site of metastases rather than the other may help in the informed discussion with the patients about the overall outlook of their disease; moreover, this could help tailor systemic therapy strategies for this disease.

Despite the differences in our analysis between patients affected with different isolated sites of metastases, there was no difference in general between patients affected with single site versus multiple sites of metastases. This is in contrast to lung cancer where prognostic differences have been found according to this parameter[12,13].

The current analysis showed that married patients have better overall and pancreatic cancer specific survival compared to unmarried patients. This is in line with previous SEER analyses for pancreatic cancer patients[14] as well as for many other solid tumors[15,16]. Moreover, the current analysis showed an evidence for age and racial differences in survival outcomes. This confirms the findings from previous SEER analyses[17-19] and the racial differences may be explained by disparities in the access to care; while the impact of age may be explained by differences in baseline co morbid conditions. Our analysis showed also that male patients have poorer survival outcomes compared to female patients. This may be explained by unreported differences in co-morbid conditions.

Value of local treatment of the primary in cases of a metastatic solid tumor has been shown for metastatic renal cell carcinoma[20], metastatic non-functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors[21,22] and hepatocellular carcinoma[23]. Similar strategy is currently being explored in a number of ongoing studies for patients with metastatic breast cancer[24,25].

For pancreatic adenocarcinoma, there is no evidence-based consensus about whether and when to use surgery in the setting of metastatic disease. While older retrospective studies suggested no benefit from surgical resection to the primary tumor and synchronous liver metastases[26,27], more recent retrospective studies suggested that primary tumor resection following favorable response to systemic chemotherapy in stage IV patients may be considered in highly selected patients[28,29]. However, the number of patients in all these studies was not large enough to derive clear recommendations. Moreover, these studies still carry the methodological defects of a retrospective analysis.

The presence of liver metastases was shown in our analysis as a poor prognostic factor compared to lung or distant nodal metastases. This result is in line with the post-hoc analysis of the MPACT phase III study as well as another retrospective study[30,31]. However, our analysis differs in being on a much larger sample size which may give a more representative picture of the routine daily practice.

The results of this analysis have to be interpreted with caution given the inherent difficulties in conducting retrospective studies in general and SEER analyses in particular; most notably the lack of information about the co-morbidities in evaluated patients as well as the absence of systemic therapy information. Patients who are offered surgical resection are more likely to have better general health and less co- morbidities; thus, potential selection bias could not be totally excluded. Moreover, an important site of metastasis from pancreatic cancer-that is peritoneal deposits- is not detailed in the SEER database which may confound further the conclusions from this analysis.

Prospective controlled studies are thus needed in order to evaluate the best way to integrate local and systemic therapies in the management of pancreatic cancer patients with good general condition and limited resectable extrapancreatic disease. This is especially important given the plethora of newer systemic therapy agents approved or evaluated in the management of this disease.

The current analysis evaluated surgical options for metastatic patients; however, other local therapies (which are not detailed in the SEER database) should also be evaluated within clinical trials in these patients including interventional radiology ablative techniques (e.g., radiofrequency or microwave ablation) as well as stereotactic body radiotherapy.

The biological behavior of pancreatic cancer patients presenting with a first site of metastasis other than the liver needs to be interpreted in light of our recent understanding of the different molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer[32]. Those patients may have a peculiar molecular phenotype and thus may benefit from a different course of systemic therapy.

In conclusion, based on the SEER analysis, pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients with isolated liver metastases have worse outcomes compared to patients with isolated lung or distant nodal metastases. Further research is needed to identify the highly selected subset of patients who may benefit from local treatment of the primary tumor and/or metastatic disease.

COMMENTS

Background

Population-based data on the prognostic value of site-specific metastases for pancreatic adenocarcinoma are scarce. The authors sought to evaluate this parameter in patients registered within the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database (SEER) database.

Research frontiers

SEER database (2010-2013) has been queried through SEER*Stat program to determine the presentation, treatment outcomes and prognostic outcomes of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma according to the site of metastasis.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Patients with isolated distant nodal involvement or lung metastases have better overall and pancreatic cancer-specific survival compared to patients with isolated liver metastases (for overall survival: lung vs liver metastases: P < 0.0001; distant nodal vs liver metastases: P < 0.0001) (for pancreatic cancer-specific survival: lung vs liver metastases: P < 0.0001; distant nodal vs liver metastases: P < 0.0001).

Applications

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients with isolated liver metastases have worse outcomes compared to patients with isolated lung or distant nodal metastases.

Peer-review

This is a straightforward manuscript in which, based on the SEER analysis, the authors have shown that pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients with isolated liver metastases have worse outcomes compared to patients with isolated lung or distal nodal metastases. The paper reports a potentially interesting, practically important and original data. The authors provided sufficient methodological detail. Statistical analysis is well done. The claims are appropriately discussed. Overall, the paper is clear and well written.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Switzerland

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent statement: As this study is based on a publicly available database without identifying patient information, informed consent was not needed.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Data sharing statement: Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at omar.abdelrhman@med.asu.edu.eg. Consent was not obtained but the presented data are anonymized and risk of identification is low.

Peer-review started: October 11, 2016

First decision: December 19, 2016

Article in press: February 8, 2017

P- Reviewer: Seicean A, Swierczynski JT, Yang F S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Ma J, Jemal A. The rise and fall of cancer mortality in the USA: why does pancreatic cancer not follow the trend? Future Oncol. 2013;9:917–919. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simard EP, Ward EM, Siegel R, Jemal A. Cancers with increasing incidence trends in the United States: 1999 through 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:118–128. doi: 10.3322/caac.20141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steen W, Blom R, Busch O, Gerhards M, Besselink M, Dijk F, Festen S. Prognostic value of occult tumor cells obtained by peritoneal lavage in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer and no ascites: A systematic review. J Surg Oncol. 2016;114:743–751. doi: 10.1002/jso.24402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Y, Che X, Zhang J, Huang H, Zhao D, Tian Y, Li Y, Feng Q, Zhang Z, Jiang Q, et al. Long-term results of intraoperative electron beam radiation therapy for nonmetastatic locally advanced pancreatic cancer: Retrospective cohort study, 7-year experience with 247 patients at the National Cancer Center in China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4861. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varghese AM, Lowery MA, Yu KH, O’Reilly EM. Current management and future directions in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2016;122:3765–3775. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirri E, Castro FA, Kieschke J, Jansen L, Emrich K, Gondos A, Holleczek B, Katalinic A, Urbschat I, Vohmann C, et al. Recent Trends in Survival of Patients With Pancreatic Cancer in Germany and the United States. Pancreas. 2016;45:908–914. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Worni M, Guller U, White RR, Castleberry AW, Pietrobon R, Cerny T, Gloor B, Koeberle D. Modest improvement in overall survival for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: a trend analysis using the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results registry from 1988 to 2008. Pancreas. 2013;42:1157–1163. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318291fbc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deeb A, Haque SU, Olowokure O. Pulmonary metastases in pancreatic cancer, is there a survival influence? J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;6:E48–E51. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2014.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemke J, Scheele J, Kapapa T, Wirtz CR, Henne-Bruns D, Kornmann M. Brain metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:4163–4173. doi: 10.3390/ijms14024163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar A, Dagar M, Herman J, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Laheru D. CNS involvement in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a report of eight cases from the Johns Hopkins Hospital and review of literature. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:5–8. doi: 10.1007/s12029-014-9667-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. About the SEER Program. Accessed June 25, 2016. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/about.

- 12.Ren Y, Dai C, Zheng H, Zhou F, She Y, Jiang G, Fei K, Yang P, Xie D, Chen C. Prognostic effect of liver metastasis in lung cancer patients with distant metastasis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:53245–53253. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riihimäki M, Hemminki A, Fallah M, Thomsen H, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. Metastatic sites and survival in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014;86:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang XD, Qian JJ, Bai DS, Li ZN, Jiang GQ, Yao J. Marital status independently predicts pancreatic cancer survival in patients treated with surgical resection: an analysis of the SEER database. Oncotarget. 2016;7:24880–24887. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He XK, Lin ZH, Qian Y, Xia D, Jin P, Sun LM. Marital status and survival in patients with primary liver cancer. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11066. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin JJ, Wang W, Dai FX, Long ZW, Cai H, Liu XW, Zhou Y, Huang H, Wang YN. Marital status and survival in patients with gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 2016;5:1821–1829. doi: 10.1002/cam4.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheung R. Racial and social economic factors impact on the cause specific survival of pancreatic cancer: a SEER survey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:159–163. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amin S, Lucas AL, Frucht H. Evidence for treatment and survival disparities by age in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a population-based analysis. Pancreas. 2013;42:249–253. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31825f3af4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy MM, Simons JP, Ng SC, McDade TP, Smith JK, Shah SA, Zhou Z, Earle CC, Tseng JF. Racial differences in cancer specialist consultation, treatment, and outcomes for locoregional pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2968–2977. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0656-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heng DY, Wells JC, Rini BI, Beuselinck B, Lee JL, Knox JJ, Bjarnason GA, Pal SK, Kollmannsberger CK, Yuasa T, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with synchronous metastases from renal cell carcinoma: results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium. Eur Urol. 2014;66:704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keutgen XM, Nilubol N, Glanville J, Sadowski SM, Liewehr DJ, Venzon DJ, Steinberg SM, Kebebew E. Resection of primary tumor site is associated with prolonged survival in metastatic nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Surgery. 2016;159:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hüttner FJ, Schneider L, Tarantino I, Warschkow R, Schmied BM, Hackert T, Diener MK, Büchler MW, Ulrich A. Palliative resection of the primary tumor in 442 metastasized neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas: a population-based, propensity score-matched survival analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2015;400:715–723. doi: 10.1007/s00423-015-1323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdel-Rahman O. Role of liver-directed local tumor therapy in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic metastases: a SEER database analysis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11:183–189. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2017.1259563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shien T, Nakamura K, Shibata T, Kinoshita T, Aogi K, Fujisawa T, Masuda N, Inoue K, Fukuda H, Iwata H. A randomized controlled trial comparing primary tumour resection plus systemic therapy with systemic therapy alone in metastatic breast cancer (PRIM-BC): Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG1017. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42:970–973. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruiterkamp J, Voogd AC, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Bosscha K, van der Linden YM, Rutgers EJ, Boven E, van der Sangen MJ, Ernst MF. SUBMIT: Systemic therapy with or without up front surgery of the primary tumor in breast cancer patients with distant metastases at initial presentation. BMC Surg. 2012;12:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-12-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gleisner AL, Assumpcao L, Cameron JL, Wolfgang CL, Choti MA, Herman JM, Schulick RD, Pawlik TM. Is resection of periampullary or pancreatic adenocarcinoma with synchronous hepatic metastasis justified? Cancer. 2007;110:2484–2492. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dünschede F, Will L, von Langsdorf C, Möhler M, Galle PR, Otto G, Vahl CF, Junginger T. Treatment of metachronous and simultaneous liver metastases of pancreatic cancer. Eur Surg Res. 2010;44:209–213. doi: 10.1159/000313532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright GP, Poruk KE, Zenati MS, Steve J, Bahary N, Hogg ME, Zuriekat AH, Wolfgang CL, Zeh HJ, Weiss MJ. Primary Tumor Resection Following Favorable Response to Systemic Chemotherapy in Stage IV Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma with Synchronous Metastases: a Bi-institutional Analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1830–1835. doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crippa S, Bittoni A, Sebastiani E, Partelli S, Zanon S, Lanese A, Andrikou K, Muffatti F, Balzano G, Reni M, et al. Is there a role for surgical resection in patients with pancreatic cancer with liver metastases responding to chemotherapy? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:1533–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.06.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabernero J, Chiorean EG, Infante JR, Hingorani SR, Ganju V, Weekes C, Scheithauer W, Ramanathan RK, Goldstein D, Penenberg DN, et al. Prognostic factors of survival in a randomized phase III trial (MPACT) of weekly nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine alone in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Oncologist. 2015;20:143–150. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suenaga M, Fujii T, Kanda M, Takami H, Okumura N, Inokawa Y, Kobayashi D, Tanaka C, Yamada S, Sugimoto H, et al. Pattern of first recurrent lesions in pancreatic cancer: hepatic relapse is associated with dismal prognosis and portal vein invasion. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:1756–1761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bailey P, Chang DK, Nones K, Johns AL, Patch AM, Gingras MC, Miller DK, Christ AN, Bruxner TJ, Quinn MC, et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]