Abstract

We have used multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and serotyping to build a phylogenetic framework for pneumococcal disease isolates in Scotland that provides a snapshot of the relationships between capsular type and genotype. The results show that while the MLST type correlates with the serotype, isolates within a serotype can belong to a number of individual clonal complexes or sequence types (STs). We also show that isolates of the same ST can express different capsular polysaccharides, i.e., display capsular switching, and that this phenomenon is observed both for capsular types commonly isolated from patients with invasive disease and for serogroups less commonly isolated from patients with invasive disease but which may commonly be carried asymptomatically in the human nasopharynx.

Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus) is a major etiological agent of meningitis, septicemia, pneumonia, sinusitis, and otitis media worldwide. A number of studies have demonstrated the role of the polysaccharide capsule in the virulence of the pneumococcus (12, 13, 21). The antimicrobial resistance levels of this organism are increasing worldwide. One of the strategies used to reduce both the incidence of invasive disease and the spread of antibiotic-resistant isolates is the administration of vaccines directed against the polysaccharide capsule of this organism. Pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate (Pnc) vaccines consist of a protein antigen carrier conjugated to various pneumococcal polysaccharides in order to induce a T-cell-dependent immune response.

Immunochemistry of the pneumococcal capsule has divided pneumococci into more than 90 serotypes. The prevalence of serotypes recovered from patients with invasive disease is used to guide their inclusion in conjugate vaccines. A single serotype may include a number of genetically diverse clones distinguishable by techniques such as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (1, 9). This situation is thought to have arisen through the horizontal recombination of pneumococcal DNA due to natural transformability in the pneumococcus (3-5). It is also possible for capsule genes to undergo recombination via this mechanism; the results of such an event are pneumococci of a single clonal type which express different capsule genes, i.e., different serotypes. This phenomenon is known as capsular switching. Knowledge of the extent of these two phenomena within pneumococcal populations is limited because the data for isolates that have been collected are skewed; and those data are usually limited to antibiotic-resistant populations, specific age groups, or invasive isolates. More recent studies have begun to address these deficiencies by examining the genetic heterogeneities of invasive pneumococci and those organisms carried asymptomatically in the human nasopharynx and the contribution of the capsular serotype and the genotype to the disease-causing abilities of pneumococci. In particular, work on carriage isolates (1, 17) suggests that the level of capsule switching may be relatively low and that the capsular type of a pneumococcus may be more important than the underlying genotype for the invasiveness of the organism (1). However, a subsequent study (17) has concluded that clonal properties, in addition to the capsular type, may be important in determining invasive potential. Knowledge of clonal types and the extent of capsule switching is important in understanding or predicting the impact of pneumococcal vaccine programs, since these programs may provide selection pressure for virulent genotypes to switch capsules and escape coverage by the Pnc vaccines (20).

The aim of this study was to assess the level of genetic diversity and investigate the relationships between capsular type and genotype in diverse disease-causing pneumococci by use of a wide range of serotypes (not preselected for antibiotic resistance, disease type, or patient age) submitted to a national reference laboratory.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The strains used in this study were clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae sent to the Scottish Meningococcus and Pneumococcus Reference Laboratory (SMPRL), Glasgow, from routine diagnostic bacteriology laboratories in Scotland. Invasive strains were included as part of an enhanced pneumococcal surveillance program on the basis of their isolation from normally sterile body sites. To maximize diversity, a number of strains from miscellaneous sites were also included. Strains were isolated on Columbia agar plates (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) at 37°C under anaerobic conditions by use of an anaerobic pack (Oxoid) and after a single subculture were stored at −80°C on Protect beads (M-Tech Diagnostics, Warrington, United Kingdom). Isolates were serotyped by coagglutination, as described previously (11, 19). The 252 isolates (190 blood isolates, 8 cerebrospinal fluid isolates, 22 eye isolates, 9 ear isolates, 7 sputum isolates, and 16 isolates from miscellaneous sources) were initially selected on the basis of serogroup to include at least five members of each serogroup when they were available. The collection includes pneumococci of 39 serotypes and represents the full range of serotypes sent to SMPRL, including more uncommon serotypes (Table 1). Isolates from all health boards in Scotland were included in the study and were collected between 1996 and 2003. Duplication of strains was avoided by choosing geographically and chronologically separate isolates of each serogroup.

TABLE 1.

Heterogeneity within serotypes of 252 disease-associated pneumococcal isolates

| Serotypea | Total no. of isolates | No. of STs | ST(s) (no. of isolates)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 3 | 227* (7), 304 (2), 306 (1) |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 74 (1) |

| 3 | 13 | 4 | 180 (10), 232 (1), 593 (1), 311* (1) |

| 4 | 12 | 4 | 205 (3), 206 (3), 246 (5), 584 (1) |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 569 (1) |

| 6A | 8 | 5 | 65 (4), 581 (1), 460 (1), 813 (1), 814 (1) |

| 6B | 6 | 4 | 90 (1), 96 (3), 138 (1), 176 (1) |

| 7F | 13 | 1 | 191* (13) |

| 8 | 12 | 3 | 53 (10), 578 (1), 815 (1) |

| 9N | 2 | 2 | 66* (1), 405 (1) |

| 9V | 13 | 8 | 66* (1), 156* (4), 162* (3), 163 (1), 311* (1), 467 (1), 834 (1), 860 (1) |

| 10 | 2 | 2 | 97* (1), 585 (1) |

| 10A | 4 | 2 | 97 (3), 816 (1) |

| 10F | 1 | 1 | 597 (1) |

| 11A | 11 | 3 | 62 (8), 113* (1), 408 (2) |

| 12F | 11 | 3 | 216 (1), 218 (9), 989 (1) |

| 13 | 2 | 2 | 70 (1), 574 (1) |

| 14 | 15 | 5 | 9 (8), 124 (3), 143 (1), 156* (2), 191* (1) |

| 15 | 3 | 3 | 73 (1), 199* (1), 1000 (1) |

| 15A | 1 | 1 | 817 (1) |

| 15B | 5 | 3 | 199* (3), 579 (1), 583 (1) |

| 16F | 6 | 5 | 30 (1), 414 (2), 570 (1), 576 (1), 590 (1) |

| 17F | 6 | 3 | 275 (1), 392 (4), 980 (1) |

| 18C | 8 | 4 | 113* (5), 114 (1), 119 (1), 818 (1) |

| 18F | 3 | 3 | 223 (1), 496 (1), 594 (1) |

| 19A | 2 | 1 | 199* (2) |

| 19F | 9 | 7 | 162* (2), 227 (1), 271 (1), 285 (1), 320 (2), 586 (1), 587 (1), 227* (1) |

| 20 | 7 | 2 | 235 (6), 591 (1) |

| 22F | 10 | 5 | 433 (6), 565 (1), 588 (1), 698 (1), 819 (1) |

| 23F | 12 | 5 | 33 (1), 36 (2), 40 (2), 311* (6), 573 (1) |

| 24 | 3 | 3 | 72 (2), 580 (1), 685 (1) |

| 27 | 1 | 1 | 571 (1) |

| 29 | 3 | 3 | 558* (1), 575 (1), 582 (1) |

| 31 | 8 | 5 | ST444 (4), 567 (1), 568 (1), 837 (1), 596 (1) |

| 33F | 9 | 5 | 60 (3), 100 (3), 592 (1), 673 (1), 981 (1) |

| 35B | 3 | 3 | 377 (1), 558* (1), 593* (1) |

| 35F | 4 | 3 | 446 (2), 448 (1), 572 (1) |

| 38 | 2 | 1 | 393 (2) |

| 41 | 1 | 1 | 589 (1) |

| Nontypeable | 8 | 5 | 113* (1), 138 (1), 156 (1), 448 (4), 577 (1) |

Serotypes in boldface type denote the seven-valent Pnc vaccine capsular types.

STs in boldface type denote the prevalent ST of vaccine serotypes (1). Asterisks denote STs containing pneumococci of multiple serotypes.

MLST was performed with all isolates as described previously (2, 6, 11). Briefly, fragments from the seven housekeeping genes, aroE, gdh, gki, recP, spi, xpt, and ddl, were amplified from pneumococcal lysates with the primers described by Enright and Spratt (6) by using a single PCR cycle. The cleaned PCR products were then sequenced with the same primers and dideoxy dye-labeled terminators (DYEnamic ET Terminator sequencing premix; Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) and cleaned again. These steps were carried out by using a robotic platform (MWG, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom) and a MegaBACE automated capillary electrophoresis system (Amersham Biosciences). Analysis of sequence types (STs) and assignment to clonal complexes was performed with the BURST (based upon related sequence types) program (8). This program compares allelic profiles and assigns a founder ST to the member of the group which contains the most alleles present within that group. Further analysis of relationships between pneumococcal STs was done by concatamerizing the DNA sequences of the seven alleles by using the software available at www.mlst.net and aligning the resulting sequences by using the Clustal W interface (www.ebi.ac.uk/clustal). A phylogentic tree was then produced from the alignment data by using the Tree View program of the PHYLIP package of software (http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/rod/treeview.html).

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was carried out as follows: MICs were obtained with E-test strips (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). E-test inoculum preparation and plating, strip application, and subsequent MIC determinations were carried out in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Breakpoints for susceptibility were derived from values given by the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (www.BSAC.org.uk; version 2.1.5, November 2003; last accessed on 31 May 2004). Penicillin resistance is an MIC of ≥2 mg/liter, intermediate resistance is an MIC of 0.12 to 1.0 mg/liter. Erythromycin resistance is an MIC of >1 mg/liter.

RESULTS

The 252 isolates in our collection were of 39 different serotypes, and 8 nontypeable isolates were also included (Table 1). A total of 109 STs were assigned. Forty STs were new to the MLST database (Table 2). The mean age of the patients was 44.6 years (age range, <1 month to 103 years).

TABLE 2.

New STs first identified during this study and deposited in the MLST database

| ST | Serotype | Profile |

|---|---|---|

| 565 | 22F | 1, 1, 4, 34, 18, 58, 17 |

| 567 | 31 | 1, 2, 29, 18, 34, 4, 18 |

| 568 | 31 | 1, 2, 29, 18, 6, 4, 18 |

| 569 | 5 | 1, 3, 4, 7, 6, 40, 29 |

| 570 | 16F | 1, 5, 27, 5, 1, 1, 76 |

| 571 | 27 | 1, 5, 27, 24, 1, 40, 14 |

| 572 | 35F | 1, 7, 4, 19, 10, 40, 27 |

| 573 | 23F | 1, 8, 9, 1, 34, 4, 6 |

| 574 | 13 | 2, 1, 1, 1, 6, 31, 14 |

| 575 | 29 | 2, 5, 2, 1, 6, 28, 6 |

| 576 | 16F | 2, 5, 27, 5, 1, 1, 76 |

| 577 | NTa | 2, 9, 1, 11, 16, 3, 14 |

| 578 | 8 | 2, 12, 1, 11, 16, 3, 14 |

| 579 | 15B | 2, 13, 2, 4, 1, 1, 1 |

| 580 | 24 | 6, 9, 4, 10, 34, 5, 14 |

| 581 | 6A | 8, 5, 2, 1, 6, 1, 17 |

| 582 | 29 | 8, 13, 4, 8, 3, 22, 34 |

| 583 | 15B | 8, 13, 14, 23, 17, 4, 14 |

| 584 | 4 | 10, 5, 17, 13, 13, 10, 1 |

| 585 | 10A | 10, 7, 44, 2, 10, 1, 27 |

| 586 | 19F | 10, 20, 14, 1, 42, 3, 29 |

| 587 | 19F | 12, 12, 2, 5, 9, 48, 6 |

| 588 | 22F | 13, 1, 4, 1, 18, 58, 17 |

| 589 | 41 | 13, 48, 53, 17, 14, 12, 31 |

| 590 | 16F | 15, 8, 8, 5, 1, 1, 1 |

| 591 | 33F | 15, 33, 8, 18, 15, 31, 31 |

| 592 | 3 | 18, 5, 23, 18, 10, 3, 1 |

| 593 | 35B | 18, 7, 4, 19, 10, 40, 27 |

| 594 | 18F | 28, 5, 9, 18, 6, 11, 14 |

| 596 | 31 | 1, 2, 29, 1, 9, 14, 18 |

| 597 | 10F | 2, 53, 11, 1, 6, 19, 31 |

| 813 | 6A | 7, 25, 4, 5, 15, 20, 28 |

| 814 | 6A | 8, 5, 4, 15, 10, 20, 6 |

| 815 | 8 | 2, 5, 14, 1, 16, 1, 29 |

| 816 | 10A | 5, 40, 4, 19, 10, 1, 27 |

| 817 | 15A | 1, 5, 12, 5, 6, 15, 6 |

| 818 | 18C | 7, 4, 9, 5, 6, 16, 18 |

| 819 | 22F | 1, 1, 4, 1, 18, 58, 18 |

| 980 | 17F | 7, 5, 15, 1, 6, 31, 14 |

| 981 | 33F | 10, 41, 47, 42, 6, 14, 17 |

NT, nontypeable.

The majority of isolates were penicillin susceptible (MIC < 0.12 mg/liter; n = 214). The collection contained just two isolates for which the penicillin MIC was 2 μg/ml. Both of these strains were found to be of serotype 19F (ST320 from the MLST database; this ST is associated with a multidrug-resistant clone in the Far East). There were 26 erythromycin-resistant isolates. These were found to be of STs 9, 90, 143, 156, 180, 814, 860, 271, 285, 320, 377, and 1000.

Analysis of isolates.

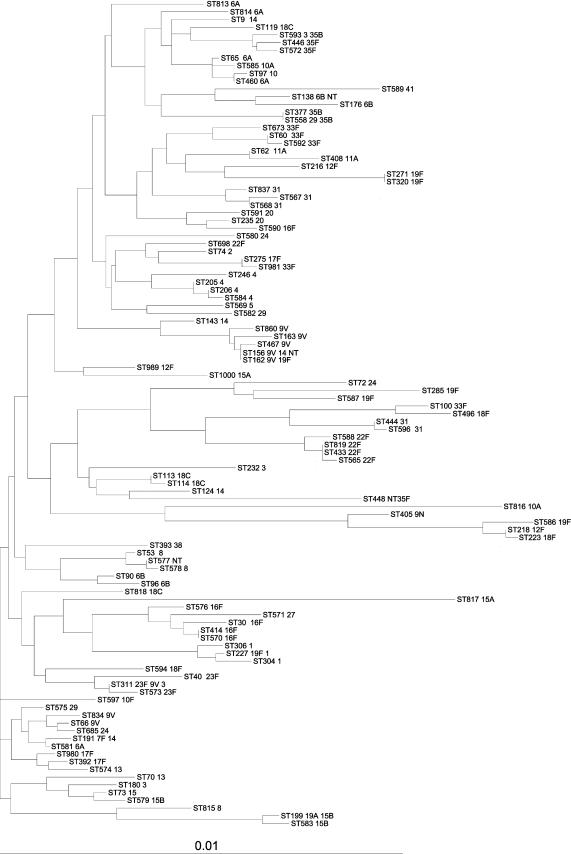

Isolates were compared on the basis of their serotypes, allelic profiles, and STs. The results of the BURST analysis, by which the major clonal groups were identified, are shown in Table 3, which provides the major clonal groups and summarizes the relationships between the members of the groups. Single-, double-, or triple-locus variants of the member STs and their frequencies are shown in Table 3. This analysis determines the relatedness of strains within a clonal group. Figure 1 shows these relationships in the form of a phylogenetic tree drawn from the concatenated allele sequences from each ST.

TABLE 3.

Major clonal groups identified by BURST analysisa

| Groupb and ST | No. of isolates

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-locus variants | Double-locus variants | Triple-locus variants | |

| 1 | |||

| 162 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| 156 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 467 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 163 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 860 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | |||

| 433 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 819 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 565 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 588 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | |||

| 414 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 570 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 30 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 576 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | |||

| 460 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 97 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 65 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 585 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 5 | |||

| 572 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 446 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 593 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | |||

| 66 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 834 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 685 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | |||

| 40 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 311 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 573 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | |||

| 53 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 577 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 578 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | |||

| 218 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 405 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 223 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

There are a further 13 clonal groups with two STs per group, meaning that founders cannot be ascribed. Fifty-one singleton STs were also identified. Each ST was represented by one isolate.

The predicted founder was ST162. The predicted founder of group 2 was ST433. Multiple candidates were predicted to be founders for groups 3 and 4. The predicted founders of groups 6 and 9 were ST66 and ST218, respectively. Multiple candidates were predicted to be founders of groups 5, 7, and 8.

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram constructed from concatenated sequences of MLST alleles found in this study.

Serotype 1.

Serotype 1 isolates fell into three STs that did not group together by BURST analysis (Table 3); however, they shared sequence similarity (ST227 shared five of seven and four of seven alleles with ST306 and ST304, respectively, and ST304 and ST306 shared five alleles and clustered together on the dendrogram) (Fig. 1). ST306 is a major invasive serotype 1 clone recovered in Sweden in the late 1990s (data from MLST website).

Serotype 3.

Serotype 3 isolates showed high levels of diversity, with four STs present among 13 isolates. One of the STs present in this group (ST311) is also present in our collection but has different capsular types. Isolates of this ST deposited in the MLST database have only been of serogroup or serotype 23 and 23F. Here we report that ST311 strains present as serotypes 3, 9V, and 23F. ST311 fell into BURST group 7, which contained serotype 23F isolates of ST40 and ST573.

Serotype 5.

Only one isolate of rare serotype 5 was available for this study. This isolate was found to be of a novel ST (ST569). No ST in the MLST database had more than three alleles that matched ST569.

Serotype 6A.

Eight isolates of serotype 6A were present in our collection; these were divided into five STs. STs 65 and 460 were single-locus variants and were present in BURST group 4, along with ST585 and ST97, both of which were serogroup 10 isolates. ST581 was a single-locus variant of ST191, and ST581 appeared as both serotype 14 and serotype 7F. The two remaining serotype 6A STs, ST813 and ST814, were unrelated to other isolates in our collection and are also new to the MLST database.

Serotype 6B.

Four different STs were present in the six serotype 6B pneumococci included in this study. STs 90 and 96 were single-locus variants and formed group 15 in the BURST analysis. STs 176 and 138 were related and were one node apart on the dendrogram in Fig. 1. ST138 was also present as a nontypeable isolate. ST90 is the ST of the internationally prevalent invasive penicillin-resistant Spain 6B-2 clone. ST96 is part of the same clonal complex as ST90 and has not previously been reported to the MLST database from a serotype 6B pneumococcus but has been reported once from a serotype 6A pneumococcus.

Serotype 7F.

Serotype 7F appeared to be highly clonal. All serotype 7F pneumococci in our collection were of the same sequence type, ST191. This finding is replicated in the MLST database, in which 28 ST191 clones have been reported, and all of these were of serogroup 7 or serotype 7F. The data in the MLST database suggest that this clone is associated with invasive disease in the United Kingdom.

Serotype 8.

The majority of serotype 8 isolates in our collection were of one clonal group related to ST53. However, the MLST database showed that 15 different STs have been reported for 24 isolates of this serotype. Therefore, Scottish isolates of this serotype appear to be more clonal than those deposited in the MLST database.

Serotype 9V.

Serotype 9V displayed the highest number of STs of any of the serotypes in this study (eight STs among 13 isolates). Five of these STs were part of a large clonal group, which included the invasive, globally disseminated, penicillin-resistant clone Spain 9V-3 (4). Four of the STs found among strains of this serotype in our collection were also found to have alternative capsules, and further capsular variants for these STs have been reported in the MLST database.

ST162 is the founder of a clonal complex that includes STs 163, 156, 467, and 860. ST162 was also found among strains of serotype 19F in this study and has been reported among serotype 14 and 24F isolates in the MLST database.

ST156 is the ST of the Spain 9V-3 clone. This ST was also found among serotype 14 and nontypeable strains in our collection and has been reported for additional serotype 11A and 19F strains in the MLST database.

Serotypes 10A and 10F.

In addition to ST97, this study found two novel STs (ST816 and ST585) among serotype 10A isolates. ST597, an additional novel ST, was reported for a serotype 10F isolate.

Serotype 11A.

The majority of serotype 11A pneumococcal isolates in our collection fell into a single clonal group related to ST62. We also isolated a single isolate of ST113. Our study also found this ST for a serotype 18C isolate and a nontypeable isolate. So far the MLST database has reported this ST only for serotype 11A strains.

Serotype 12F.

The three STs for serotype 12F isolates in our collection (ST218, ST216, and ST989) were unrelated by BURST analysis.

Serotype 13.

Two unrelated STs were found for our serotype 13 isolates. Neither of these STs was closely related to other STs in our collection (singletons by BURST analysis).

Serotype 14.

Serotype 14 is the most common disease-causing serotype in Scotland. The highly prevalent erythromycin-resistant clone known as England 14-9 (10), the most common cause of invasive disease in the United Kingdom, is ST9. Our collection included 15 isolates of serotype 14. Eight isolates were of ST9; the majority were from blood cultures. All eight isolates displayed resistance to erythromycin and were penicillin sensitive. Three isolates were of ST124. This ST is a major serotype 14 ST associated with invasive disease. The collection contained a single isolate of ST143 that displayed low-level penicillin resistance (MIC = 0.5 mg/liter) and that was highly resistant to erythromycin. Two of the serotype 14 isolates in our collection were of ST156. This ST is a serotype 14 variant of the Spain 9V-3 clone (see above). We also detected this ST for a serotype 9V isolate and for a nontypeable isolate. In the MLST database, ST191 has not been previously linked with serotype 14 and has been linked only with serotype 7F and nontypeable isolates; we detected this ST for a serotype 14 isolate.

Serogroup 15.

Two isolates in the collection were found to cross-react with type A and type B sera, so they were classified as serogroup 15. These were ST199 and ST73, respectively. ST199 was recorded for five further isolates in our collection, three of which were serotype 15B and two of which were serotype 19A. This ST is present in the MLST database in serotype 6, 15B, and 19A isolates.

Serotype 16F.

There were six serotype 16F isolates in our collection; these were split into five different STs. Four of these STs were part of the same clonal complex. The remaining ST was unrelated and has no single- or double-locus variants in the MLST database. Information on serotype 16F pneumococci deposited in the MLST database shows 11 different STs among 18 isolates.

Serotype 18C.

The eight examples of serotype 18C divided into four STs, two of which (ST113 and ST114) formed a clonal complex. In our study ST113 was also found for serotype 11A isolates and a nontypeable isolate.

Serotype 18F.

There is no serotype 18F in the MLST database. Our collection contained three isolates of this serotype (ST223, ST496, and ST594, respectively). In the MLST database, ST223 has previously been associated only with serotype 12F. Our data show that this ST occurs in the same clonal complex as ST218 and ST405, which are serotypes 12F and 9N, respectively.

Serotype 19A.

ST199 displays a capsular switch. In addition to two serotype 19A isolates, we also found ST199 in serogroups or serotypes 15 and 15B. It is present in the MLST database as serogroups or serotypes 15B, 19, and 6.

Serotype 19F.

ST162 also displayed a capsular switch (see the results for serotype 9V above). This ST is part of the largest clonal complex in this study. The majority of ST227 isolates in our study were of serotype 1 and are described above. However, one serotype 19F isolate with this ST was also recorded. In the MLST database, only serotype 1 strains have this ST.

One isolate of ST271 was reported for serotype 19F. This ST is highly related to the globally prevalent antibiotic-resistant clone Taiwan 19F-14 (ST236) (18).

Serotype 22F.

Ten serotype 22F isolates were studied as part of this work. Six of these isolates were of ST433. The remaining four isolates were each of a novel ST (STs 565, 588, 819, and 698, respectively)

Serotype 23F.

Twelve serotype 23F isolates representing five STs were included in this study. Three of the STs formed a tight clonal complex (BURST group 7), while the remaining two STs were more distantly related but still appeared to be of the same lineage (double-locus variants).

ST311 was also detected in serotype 3 and 9V isolates in our study. In the MLST database, this ST has been reported only for serogroups or serotypes 23 and 23F.

Serotype 29.

Our collection contained three serotype 29 isolates, each with a different and unrelated ST. ST575 and ST582 were both new. ST558 was also present as a serotype 35B isolate in this study, thus displaying a capsular switch. In the MLST database this ST has previously been detected only as a serotype 35 isolate.

Serotype 35B.

Three STs were represented by the three serotype 35B isolates included in this study. ST377 is the ST of the globally disseminated antibiotic-resistant clone known as Utah 35B-24 (16). ST558 is a single-locus variant of ST377. ST593 is a new ST that we also found to be a serotype 3 isolate. This ST belonged to a clonal complex that also included serotype 35F isolates (BURST group 5; Table 2).

Serotype 35F.

ST446 and ST572 are members of the clonal complex that includes ST593, as discussed above. ST448 is not related to the STs mentioned for the other serogroup 35 strains but was recorded for four nontypeable isolates. This ST has been noted only from nontypeable isolates in the MLST database and is associated with conjunctivitis (14).

Serotype 41.

ST589 is a new MLST type which was unrelated to the other STs in our collection and at present is the only serotype 41 isolate in the MLST database.

Nontypeable isolates.

The majority of nontypeable isolates in our collection were of ST448 (see above). One nontypeable isolate was found to be of ST113. Our study also found this ST among serotype 11A and 18C isolates. A nontypeable isolate of ST138 was also found; we have identified this ST as serotype 6B. The MLST database reports this ST only for pneumococci of serotypes 6A and 6B. This study found ST156 for a nontypeable isolate, in addition to serotype 9 and 14 isolates. ST577 is a novel ST found for one nontypeable NT isolate.

DISCUSSION

This study has centered around a collection of pneumococcal disease-causing isolates chosen with the aim of maximizing diversity in order to (i) determine the levels of genetic heterogeneity within serotypes by the use of MLST profiling and (ii) investigate the extent to which clones or members of a clonal group express various capsular types. In selecting samples in this way, we have shown that, in agreement with other data (1, 6, 9), pneumococcal serotypes are made up from genetically distinct clones. We also demonstrate that the levels of capsular switching may be higher than those reported previously (Table 4). We believe that this is a reflection of the wide range of serotypes included in our collection and the fact that samples were taken from both patients with invasive disease and patients with noninvasive disease. If a serotype is rare in patients with invasive disease, it may nevertheless be commonly carried and therefore coexist in the nasopharynx with pneumococci of other serotypes. This situation could lead to the exchange of capsule genes via transformation. Such events can be predicted to be less frequent for pneumococcal clones that are not commonly isolated from carriers; however, the selection of isolates of a large range of serotypes, from patients with a variety of disease types, and from patients of different ages with no preselection for antibiotic resistance may increase the likelihood of detection of capsular switching in these pneumococci.

TABLE 4.

STs for which capsular switching was observed in this study

| ST | Serotypes in this study | Comments (reference) |

|---|---|---|

| 66 | 9N, 9V | |

| 97 | 10, 10A | |

| 113 | 11A, 18C, NT | Invasive ST; this ST was previously given an OR of 3.4 (1) |

| 156 | 14, 9V, NT | ST of globally prevalent antibiotic-resistant clone Spain 9V-3 (4) |

| 162 | 9V, 19F | Invasive ST; this ST was previously given an OR of 1.7 (1) |

| 191 | 7F, 14 | |

| 199 | 15, 15B, 19A | This ST was previously given an OR of 0.9 (1) |

| 227 | 1, 19F | |

| 311 | 23, 23F, 3, 9V | Carriage ST; this ST was previously given an OR of 0.6 (1) |

| 593 | 3, 35B | |

| 558 | 29, 35B |

The currently licensed seven-valent vaccine contains polysaccharide antigens from serotypes 4, 9V, 14, 19F, 23F, 18C, and 6B. Previous work (1) comparing carriage and disease isolates from children under 5 years old assigned odds ratios (ORs) to certain STs when the number of isolates was large enough. An OR of >1 indicates increased disease potential, and an OR of <1 indicates a decreased risk of invasiveness. One of the 10 STs in our study containing isolates of multiple serotypes was calculated to have an OR of >1 (OR for ST113 = 3.5), indicating that isolates of this ST pose a greater risk of causing invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in children than the other 9 STs. The predominant serotype among strains of this ST was 18C both in our data set and in that of Brueggemann et al. (1). The findings of Brueggemann et al. suggest that serotype is more important than genotype (ST) in the ability to cause IPD. Therefore, should a clone not previously identified as invasive acquire the capsule of a more invasive isolate, we might expect the new clone to become more invasive. If such a capsular switch results in the expression of a capsule not covered by the present vaccine, there may be potential for increased rates of IPD. STs 191 and 227 are of particular interest, as they contain strains of serotypes not covered by the present vaccine and were ascribed ORs >1 by Brueggemann et al. (1). ST191 and ST227 contain strains of serotypes 7F and 1 (STs 191 and 227, respectively), which are not covered by the present vaccine, and have ORs of 4.7 and 9.6, respectively; in addition, they contain strains of vaccine-covered serotypes 14 (ST191) and 19F (ST227). It should be noted that the pneumococci in our study were collected from patients with a wide range of ages, whereas those in the study of Brueggemann et al. (1) were from children under age 5 years, resulting in ORs specific only for individuals in that age group. Table 1 shows the serotypes covered by the present vaccine along with their prevalent STs and also shows the alternative STs found for these serotypes during this study.

Although serotype may be important in the determination of invasive potential, the suggestion that clonal properties in addition to the capsular polysaccharide may be important has also been made (17). A recent study based in Sweden found that isolates of serotype 14 included STs that were found only among carriers as well as STs that only caused invasive disease, suggesting that although these clones express the same capsule, they have different invasive potentials. This finding is supported by work from Israel, which used a mouse model of infection to investigate whether virulence could be determined independently of the polysaccharide (15). That study found that while inoculation with pneumococci of either two strains with identical pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns but different capsular types (types 14 and 9V) resulted in mortality rates statistically insignificantly different from each other, inoculation with an unrelated type 14 strain did not result in mortality in the murine model.

Our collection contained representatives of 11 of the 12 STs previously recognized as being associated with invasive disease (6). Six of these STs contain isolates of capsular types not included in the licensed vaccine; these isolates could thus cause invasive disease in immunized individuals. If the invasive properties lie with the overall genotype of the organism, including the capsular genes, rather than solely with the serotype, a vaccination program could eventually lead to an increase in these organisms and a subsequent increase in the number of cases of invasive disease. Five of these STs contained isolates of multiple serotypes, demonstrating that the potential for capsular switching exists among clones associated with invasive disease.

This study has demonstrated the presence of capsular switching among disease-causing isolates of S. pneumoniae. The results show that capsular switching is not confined to the common disease-causing clones but also occurs in isolates of serotypes and STs that are not commonly associated with invasive disease; for example, ST593 is found among isolates of serotypes 3 and 35B, and ST558 contains isolates of serotypes 35B and 29. Serotype 3 in particular has been more associated with carriage than with disease (1). The presence of multiple capsular types among clones more associated with carriage than with disease should perhaps be expected, as pneumococci are naturally transformable and readily acquire genetic material from other pneumococci, resulting in a genome in which point mutations are 50 times more likely to occur via recombination than via mutation (7). Capsular switching could be presumed to be more likely to occur in clones that are carried more frequently or for longer periods, as they will have a greater chance to be present on the mucosal surface in the presence of pneumococci with different capsule genes and therefore a higher likelihood of acquiring DNA by transformation. Strains that are rarely carried have less chance of undergoing recombination on the mucosal surface, as is the case for strains that are carried for only a short time. Capsular switching among successful disease-associated clones may be driven by selective pressure from the immune response. However, what is the evolutionary pressure that drives capsular switching if the new capsule does not increase fitness?

This study has highlighted the diversity of the pneumococcal population; this is indicated by the large number of STs that appear only once in our collection. Such low numbers mean that the extent of capsular variation within STs may be much larger than that reported here. Our data indicate that enhanced surveillance programs that use genotypic methods for isolate characterization are important for monitoring pneumococcal populations prior to, during, and after the introduction of Pnc vaccines.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Executive. This publication made use of the MLST website (http://www.mlst.net) developed by Man-Suen Chan. The development of this site is funded by the Wellcome Trust.

We thank the staff of the Scottish diagnostic microbiology laboratories for providing isolates and the staff of SMPRL for serotyping and MLST.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brueggemann, A. B., D. T. Griffiths, E. Meats, T. Peto, D. W. Crook, and B. G. Spratt. 2003. Clonal relationships between invasive and carriage Streptococcus pneumoniae and serotype- and clone-specific differences in invasive disease potential. J. Infect. Dis. 187:1424-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke, S. C., M. A. Diggle, J. A. Reid, L. Thom, and G. F. S. Edwards. 2001. Introduction of an automated service for the laboratory confirmation of meningococcal disease in Scotland. J. Clin. Pathol. 54:556-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coffey, T., M. Daniels, C. Enright, and B. Spratt. 1999. Serotype 14 variants of the Spanish penicillin-resistant serotype 9V clone of Streptococcus pneumoniae arose by large recombinational replacements of the cpsA-pbp1a region. Microbiology 145:2023-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffey, T. J., C. G. Dowson, M. Daniels, J. Zhou, C. Martin, B. G. Spratt, and J. M. Musser. 1991. Horizontal transfer of multiple penicillin-binding protein genes, and capsular biosynthetic genes, in natural populations of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2255-2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coffey, T. J., M. C. Enright, M. Daniels, J. K. Morona, R. Morona, W. Hryniewicz, J. C. Paton, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Recombinational exchanges at the capsular polysaccharide biosynthetic locus lead to frequent serotype changes among natural isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 27:73-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enright, M., and B. Spratt. 1998. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology 144:3049-3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feil, E. J., M. C. Enright, and B. G. Spratt. 2000. Estimating the relative contributions of mutation and recombination to clonal diversification: a comparison between Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Res. Microbiol. 151:465-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feil, E. J., B. C. Li, D. M. Aanensen, W. P. Hanage, and B. G. Spratt. 2004. eBURST: inferring patterns of evolutionary descent among clusters of related bacterial genotypes from multilocus sequence typing data. J. Bacteriol. 186:1518-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gertz, R. E., Jr., M. C. McEllistrem, D. J. Boxrud, Z. Li, V. Sakota, T. A. Thompson, R. R. Facklam, J. M. Besser, L. H. Harrison, C. G. Whitney, and B. Beall. 2003. Clonal distribution of invasive pneumococcal isolates from children and selected adults in the United States prior to 7-valent conjugate vaccine introduction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4194-4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall, L., R. Whiley, B. Duke, R. George, and A. Efstratiou. 1996. Genetic relatedness within and between serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the United Kingdom: analysis of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and antimicrobial resistance patterns. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:853-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jefferies, J., S. C. Clarke, M. A. Diggle, A. Smith, C. Dowson, and T. Mitchell. 2003. Automated pneumococcal MLST using liquid-handling robotics and a capillary DNA sequencer. Mol. Biotechnol. 24:303-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim, J. O., and J. N. Weiser. 1998. Association of intrastrain phase variation in quantity of capsular polysaccharide and teichoic acid with the virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 177:368-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magee, A. D., and J. Yother. 2001. Requirement for capsule in colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 69:3755-3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin, M., J. H. Turco, M. E. Zegans, R. R. Facklam, S. Sodha, J. A. Elliott, J. H. Pryor, B. Beall, D. D. Erdman, Y. Y. Baumgartner, P. A. Sanchez, J. D. Schwartzman, J. Montero, A. Schuchat, and C. G. Whitney. 2003. An outbreak of conjunctivitis due to atypical Streptococcus pneumoniae. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:1112-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizrachi Nebenzahl, Y., N. Porat, S. Lifshitz, S. Novick, A. Levi, E. Ling, O. Liron, S. Mordechai, R. K. Sahu, and R. Dagan. 2004. Virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae may be determined independently of capsular polysaccharide. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 233:147-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richter, S. S., K. P. Heilmann, S. L. Coffman, H. K. Huynh, A. B. Brueggemann, M. A. Pfaller, and G. V. Doern. 2002. The molecular epidemiology of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States, 1994-2000. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:330-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandgren, A., K. Sjostrom, B. Olsson-Liljequist, B. Christensson, A. Samuelsson, G. Kronvall, and B. Henriques Normark. 2004. Effect of clonal and serotype-specific properties on the invasive capacity of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 189:785-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi, Z.-Y., M. C. Enright, P. Wilkinson, D. Griffiths, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Identification of three major clones of multiply antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Taiwanese hospitals by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3514-3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smart, L. E. 1986. Serotyping of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains by coagglutination. J. Clin. Pathol. 39:328-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spratt, B. G., and B. M. Greenwood. 2000. Prevention of pneumococcal disease by vaccination: does serotype replacement matter? Lancet 356:1210-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson, D. A., and D. M. Musher. 1990. Interruption of capsule production in Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 3 by insertion of transposon Tn916. Infect. Immun. 58:3135-3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]