Abstract

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory multisystem disorder, affecting many systems such as lung, lymph nodes, skin and eye involvement. Nervous system involvement is often seen in 5–15% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis in the first two years. Preceding to systemic involvement the initial symptom as neurological complaints has been rarely reported. Lacking of any specific, clinical and / or radiological findings for neurosarcoidosis in these cases, it could be difficult to make an accurate diagnosis and histopathological evaluation may be required. Due to rarity and complexity diagnosis of the neurosarcoidosis, in this study, clinical, radiological and / or histopathological features, treatment modalities of the 7 neurosarcoidosis patients to be presented with detailed investigations of different neurological symptoms were evaluated.

Keywords: Sarcoidosis, neurosarcoidosis symptomatology, neurosarcoidosis treatment

INTRODUCTION

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory, multisystemic disease that can affect many organs, such as the lungs, lymph nodes, skin, and eyes. Nervous system involvement is observed in 5%–15% cases; in 70% cases, neurological symptoms occur within the first 2 years of the systemic disease onset (1). Central nervous system (CNS) involvement of sarcoidosis may affect the cranial nerves (52%), particularly the facial nerve, meninges, brain parenchyma, and hypothalamus. Various symptoms, such as encephalopathy, seizures, myelopathy, meningeal syndrome, and cerebellar involvement, may be presented (2). Diagnosis remains difficulties as there are no specific clinical and/or radiological symptoms of neurosarcoidosis (NS), mainly in patients without systemic manifestations. Diagnosis can be accurate by detecting histopathological non-caseified granulomas associated with clinical and radiological symptoms. Clinical follow-up and treatment modalities for neurosarcoidosis remain unclear because the disease is rare; early treatment is reported as important in terms of mortality and morbidity. In treatment, while corticosteroids are the first line, immunosuppressive treatments can be applied in refractory cases.

In this context, we aimed to discuss the radiological and/or histopathological characteristics and treatment modalities in 7 cases of NS as a result of detailed investigations.

CASES

Table 1 demonstrates the clinical and radiological characteristics of the patients with NS who were referred to our institution between 2006 and 2013.

Table 1.

Summery of cases

| Cases | Gender | Age | Systemic involvement | Systemic involvement age | Neurologic involvement age | Neurologic symptom and findings | Histopathologic evaluation | CSF Findings | Treatment | Clinical status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case: 1 | M | 18 | Liver | 17 | 16 | Paraparesis, dysarthria, optic nerve involvement | Yes | Mild increased protein level (48 mg/dL) OCB negative | 1000 mg/day 7 days pulse steroid and continued as l mg/kg/day oral steroid followed with MTX and cyclophosphamide | Progression |

| Case: 2 | M | 17 | (−) | (−) | 15 | Epileptic seizure | Yes | Increased protein level (471 mg/dL) OCB negative | 1000 mg/day 7 days pulse steroid and continued with 1 mg/kg/day oral steroid and antiepileptic drug threapy | Cured |

| Case: 3 | F | 39 | Lung | 37 | 37 | Epileptic seizure | No | No changes, OCB negative | 1000mg/day 7 gun pulse steroid, 1 mg/kg/day oral steroid and continued with antiepileptic | Stationary |

| Case: 4 | M | 16 | Lung | 16 | 14 | Diplopia (6. cranial nerve involvement), paraparesis | No | Low glucose level (20 mg/dL), (20 mg/dL), high protein level (178 mg/dL), OCB pattern 4 positive, high ACE level (11.1 U/L) | 1000 mg/day 7 days pulse steroid and continued with 1 mg/kg/day | Cured |

| Case: 5 | M | 55 | Lung | 45 | 54 | Hemiparesis, dysarthria | Yes | Increased in protein level (70 mg/dL), OCB negative, high ACE level (14.65 U/L) | 1000 mg/day 7 days pulse steroid and continue with 1 mg/kg/day oral steroid | Cured |

| Case: 6 | M | 45 | Lung | 34 | 41 | Diplopia (6. cranial nerve involvement) | Yes | Increased protein level (93.6 mg/dL), OCB negative, high ACE level (5.3 U/L) | 1000 mg/day 7 days pulse steroid and continued with 1 mg/kg/day oral steroid | Cured |

| Case: 7 | F | 55 | Lung | 55 | 55 | Trigeminal neuralgia | No | Increased protein level (49.2 mg/dL), high Ig G index level (0.93), OCB pattern 3 positive, high ACE level 10 U/L) | Various antiepileptic treatment for Trigeminal neuralgia | Cured |

OCB: oligoclonal band; ACE: angiotensin converting enzyme; MTX: methotrexate

Case 1

An 18-year-old male patient, with an unremarkable medical history, was admitted to in November 2010 with complaints of sudden onset of weakness in right arm and leg, blurred vision of right eye and dysarthria. A gadolinium-enhancing lesion at the right optic tract was detected in cranial MRI. Neoplastic, metabolic, and inflammatory diseases were evaluated for the etiology; however, no pathology was detected, and his complaints spontaneously resolved within 2 months.

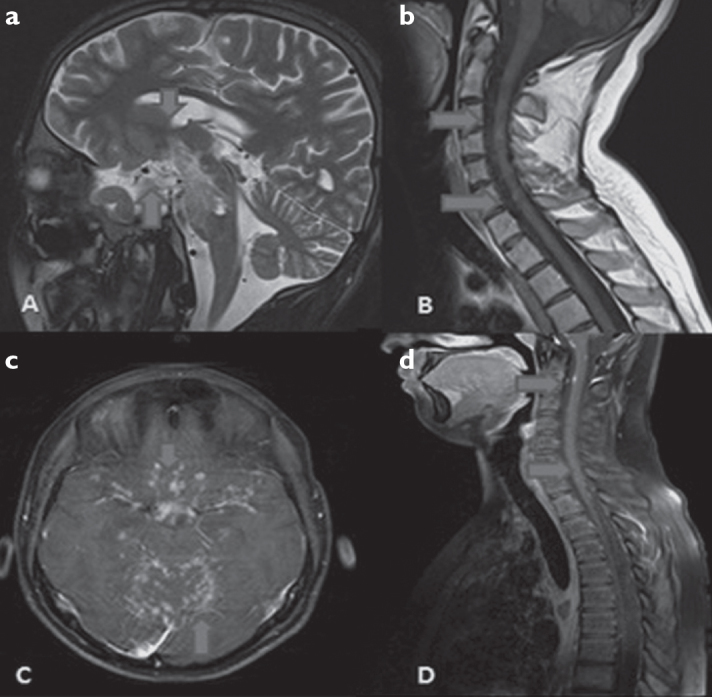

Further, a second attack with right-sided weakness and dysarthria occurred in April 2011, and cranial MRI revealed gadolinium enhanced lesions in mesencephalon and pons in addition to the optic tract. A mild protein increase in (48 mg/dL) cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination was also detected. Oligoclonal band (OCB) was found negative. He was diagnosed with sarcoidosis as a result of a liver biopsy performed because of lymphadenomegaly discerned in the liver during systemic screening. One month later (May 2011), upon acute clinical right facial paralysis, diplopia, difficulty in walking and progression of lesions in radiological images, he was administered 60 mg/day oral steroid and 6 months methotrexate (MTX) in another center. Clinical and radiological progression was detected in follow-up despite oral steroid prophylaxis, and he was referred to our clinic in July 2012. In radiological examinations, the cranial lesions were still persisting and the accompanying spinal cord atrophy and hypertintense lesions, lacking contrast involvement, in the cervical region were detected (Figure 1). Infliximab (300 mg/day) was added to the treatment; however, treatment was discontinued because of allergic side effects. Cyclophosphamide (1000 mg/day) and oral steroid (1 mg/kg/day) were prescribed. Although clinical improvement was observed, multiple active lesions continued in cranial MRIs, and he is currently being treated with an oral steroid (1 mg/kg/day) prophylaxis.

Figure 1. a–d.

a, b: Nodular type T2 and T1 hyper intense lesions in optic tract, chiasm optic and brainstem of case 1 in sagittal T2 cranial MRI and sagittal T1 cervical MRI, c, d: Partial nodular type infiltrative areas of Case 4 in axial contrasted T1 cranial MRI and sagittal T1 contrasted cervical MRI in supra-infra tentorial areas.

Case 2

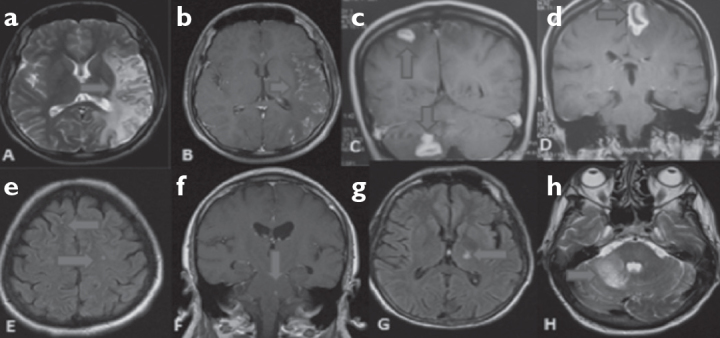

A 17-year-old male patient was referred to our clinic in June 2011 because of generalized tonic-clonic epileptic seizures for two months; a hyperintense, suspicious lesion at the left temporal region was detected in cranial MRI examination (Figure 2). His family history was unremarkable. Hemiparesis in the right upper and lower extremities was observed. A protein increase (471 mg/dL; serum protein 6.88 mg/dL) was observed in CSF examination. There was a diffuse bioelectrical disorganization and generalized epileptiform discharges at the left temporal lobe in electroencephalography (EEG) examination. Non-caseified granulomas, consistent with sarcoidosis, were observed with left temporal lobe lesion site biopsy. There was a significant decrease observed in seizure frequency and duration with the treatment of azathioprine (150 mg/day), oral steroid (initiated as 60 mg/day and decreased to 10 mg/day), and anti-epileptics (carbamazepine 900 mg/day and levetiracetam 500 mg/day). He is still being followed up without any complaint.

Figure 2. a–h.

a, b: T2 hyper intense signal increases with cortico subcortical contrasting at parieto temporal occipital regions in T2 axial cranial MRI (contrasted-non contrasted) of Case 2. c, d: T1 hyper intense lesions that produce ring appearance at left and right frontal regions in contrasted cranial MRI coronary T1 cross sections and T2 hyper intense lesion that do not lead to mass effect in left cerebellar region. e: T2 hyper intense nonspecific signal increase in deep white matter at bilateral frontal region in cranial flair MRI of Case 5. f: Contrast involving lesion at brainstem in T1 coronary cranial MRI of Case 6. g, h: T2 axial hyper intense signal increase at left cerebellar region and T1 flair hyper intense at thalamus in cranial MRI of Case 7.

Case 3

A 39-year old female patient, without any remarkable medical history, was admitted to our outpatient clinic on December 2006 because of recurrent generalized seizures over the course of a few days. EEG examination revealed diffuse bioelectrical disorganization and cranial MRI revealed gadolinium enhanced lesions at the left frontal and cerebellar regions (Figure 2). CSF evaluation was unremarkable. Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (LAP) was detected in the thorax CT, performed for differential diagnosis. She had no previous systemic complaint, and sarcoidosis was diagnosed performing the thorax biopsy. Cerebral involvement was evaluated as NS, and she was treated with an oral steroid (1 mg/kg/day) and antiepileptic (levetiracetam 1500 mg/day), following intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP) treatment (1 g/day) for 7 days. In her last follow-up examination, the frequency of the seizures remarkably reduced, and a prominent regression of lesions was observed in radiological images.

Case 4

A 16-year-old male patient was admitted to our clinic in November 2012 with a complaint of diplopia after an upper respiratory tract infection. He mentioned that 3 years ago, he was evaluated by another clinic because of an acute onset of bilateral blurred vision and paraparesis. On neurological examination, papilloedema was detected, and cranial and spinal MRIs and CSF examinations were performed. OCB was negative, and there was mild leukocytosis and increased protein in CSF. There was no other pathology in the serum other than Varicella zoster IGM positivity. Complaints spontaneously ceased within 2 months. His previous medical history and family history were unremarkable, and upon examination in our clinic, there were no symptoms except a limitation in right eye abduction. Nodular-type pial infiltration at supra-infra tentorial regions predominantly in brainstem and supracellar cistern and multiple LAPs in the cervical region were detected in cranial (Figure 1) and spinal MRIs. Furthermore, tuberculosis and malignancy were suggested as preliminary diagnosis. Laboratory and microbiological examinations were normal, excluding high serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels (72U/L). Paraneoplastic syndrome screening panel was normal. After detecting subcarinal bilateral hilar LAP in thorax CT, sarcoidosis diagnosis was confirmed by biopsy. In CSF glucose was low (20 mg/dL), protein was high (178 mg/dL), OCB pattern was 4 positive and ACE level was detected high (11.1 U/L). High dose 7 days IVMP treatment (1 gr/day) was performed after the diagnosis of NS. The patient’s clinical complaints were improved on the 7th day of treatment, and prominent regression was detected in control radiological images after 3 months.

Case 5

A 55 year-old female patient with a previous medical history of hypothyroidism, type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease was admitted with headache and facial pain in September 2012. The pain was started 1 year ago, and in May 2012, she was diagnosed as systemic sarcoidosis because of pulmonary symptoms. She was suffering with a severe electric shock like pain at least twice daily in the maxillary and mandibular area of the trigeminal nerve. The patient’s family history and neurologic examination were unremarkable; in cranial MR examination performed at 3 months of intervals, T2 hyper intense lesions were detected in bilateral cerebral hemispheres involving frontal lobe and subcortical deep white matter without contrast enhancing. Upon detecting high ACE (14.65 U/L) and protein (70 mg/dL) levels in CSF examination, the patient was diagnosed as NS. Symptomatic gabapentin (800 mg/day) was started because of these neuralgia form pains.

Case 6

A 45-year-old male patient with a previous diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis in 2001 was referred to our clinic because of sudden onset of diplopia in February 2008. There was 6th nerve paralysis of the left eye upon neurological examination. Cranial MRI performed after presuming the patient may have central nervous system involvement demonstrated hyperintense lesions in mesencephalon and pons. Serum and CSF ACE levels were 98 U/L and 5.3 U/L, CSF protein levels were high (93.6 mg/dL), and oligoclonal band (OCB) was negative. The patient was diagnosed with NS and was administered a high dose (1000 mg/day) intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP) treatment for 7 days. Complaints resolved on the 3rd day of treatment, and the patient was prescribed oral steroids for long-term treatment.

Case 7

A-55 year-old male patient presented with sudden onset right arm and leg weakness, imbalance, and dysarthria on August 2011. Upon neurological examination of the patient, who was previously diagnosed with sarcoidosis and had used intermittent oral steroid treatment since 2005, dysarthria and ataxia were the prominent clinical features. Cranial MRI revealed gadolinium enhanged lesions on the left side of thalamus and pons extended from the right brachium ponti to right cerebellum compatible with NS (Figure 2). In CSF examination, protein increased (49.2 mg/dL), IgG index 0.93 (>0.7)], ACE was 10 U/L (>2.5 U/L), and OCB was pattern 3 positive; no pathological cells were detected. The case was diagnosed as NS as the result of serum ACE level 77 U/L (8–52 U/L) and was administered high dose IVMP for 7 days after switching to prophylactic oral steroid treatment. Regression of clinical findings and MRI lesions were detected in follow-up examinations and images. The patient is still being treated with oral steroid.

DISCUSSION

Nervous system involvement is observed in 5%-15% cases of systemic sarcoidosis, and in 70% cases, neurological involvement occur within 2 years after diagnosis of sarcoidosis diagnosis (1,2). Sarcoidosis may affect cranial nerves (52%), particularly the facial nerve. Meningeal, parenchymal, and hypothalamic lesions were also observed in CNS involvement of sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis can present with variable symptoms, such as encephalopathy, seizure, myelopathy, meningeal syndrome, and cerebellar signs. NS cases have exhibited 56.6% cranial neuropathy, 33.3% epileptic seizures, 16.6% peripheral nerve system symptoms comprising neuropathy/myelopathy (1,3,4,5). Bell’s paralysis because of facial nerve and optic nerve involvement are the most common cranial neuropathies observed in NS (2,5,6,7). Moreover, diffuse cerebral vasculopathy caused clinical symptoms, such as psychosis, dementia, epileptic seizures and pseudotumor cerebri depending on dural sinus trombosis. These symptoms are observed in NS (8,9). NS tends to have a poor outcome if presented with epileptic seizures initially (5,10). In spinal cord involvement of sarcoidosis, para/tetra paresis, autonomic dysreflexia, radicular syndrome, or cauda equine syndrome can be observed because of transverse myelopathy (11,12,13,14,15).

In 2 cases followed in our clinic, sarcoidosis had been previously diagnosis, and all cases were admitted with various neurological symptoms, such as epileptic seizures, cranial neuropathy, diplopia, dysarthria, trigeminal neuralgia, and hemiparesis. Diagnosis of NS remains challenging, particularly in cases that present with only neurological symptoms, without a previous diagnosis of sarcoidosis (16,17). Cases can be diagnosed by histopathological detection of non-caseified granulomas that accompany clinical and radiological features (18,19). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most sensitive imaging method (82%–97%) in NS diagnosis. Although various intracranial and spinal lesions, such as leptomeningeal involvement and white matter lesions, can be detected, these findings are nonspecific for NS diagnosis and not correlated with its clinical symptoms (20).

CSF is a diagnostic method in NS cases. Along with the detection of nonspecific findings, such as protein increase, the levels of leukocytosis or pleocytosis, ACE (21,22), immune globulin G index, CD4:CD8 lymphocyte ratio (23), an increase of beta 2-microglobulin, and the positivity of oligoclonal band (OCB) in CSF provides important clues for NS diagnosis. However, CSF examination can be normal in NS cases (5,18,24). In 6 of our cases, an increment in protein and ACE levels was detected in CSF examinations; pattern III OCB positivity in one case and pattern IV OCB positivity in one case were observed. Similar CSF findings may be present in multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, CNS infections, and tumors. Although it is not a specific diagnostic method, high serum ACE is detected in 86.3% of NS cases. All these examinations may support diagnosis; however, NS can be accurately diagnosed with histopathological examination of the brain, meninx, pulmonary, or conjunctiva biopsies (1,2). Of the 7 cases we have presented clinically, 5 began with clinical neurological symptoms, and there were no systemic sarcoidosis findings. In 5 cases, diagnosis was accurate by detecting non-caseified granulomas in a histopathological evaluation.

As the disease is rarely observed, data including clinical follow-up and treatment in NS progressing with CNS involvement is insufficient (25). In all, 2/3 cases positively responded to treatment, and prognosis is slower and stationary in treated cases (26). In the study conducted by Ferriby et al, it has been emphasized that early treatment in NS is important for prognosis as CNS involvement is considered to have a poor prognosis (27). Furthermore, Allen et al have reported that 84% of the treated cases and 38% of the non-treated ones have neurologically recovered, and the best response to treatment has been obtained in peripheral nervous system involvement (28). NS has poorer diagnosis in young cases and cases where CNS involvement occurs in the early stages (1).

Corticosteroids are the first choice in neurosarcoidosis treatment (Table 2). Rather than other system involvement, including pulmonary involvement, treatment doses should be higher in CNS involvement (29). Usually, treatment is initiated with 1 mg/kg/dose prednisolone and is expected to continue for 6–8 months (24,30). Because of the side effects of long-term high dose oral steroid treatment, use of low-dose oral steroid together with intermittent high-dose intravenous bolus treatment is recommended. Moreover, in 2/3 of the cases with steroid treatment, clinical and radiological improvement can be maintained. Immune suppressive treatments, such as azathioprine, methotrexate (MTX), cyclosporine, or cyclophosphamide, are used in patients who do not respond to steroid treatment (31). It is reported that clinical response can be maintained at 60% with MTX treatment and 75% with cyclophosphamide treatment (32,33,34). Treatments, such as infliksimab and mycophenolate mofetil, should be considered in immunosuppressive-resistant cases (24,25,30). In our cases, treatments were arranged as 1 g dose of intravenous corticosteroid for 5–7 days and oral steroid continued by tapering. Cyclophosphamide and/or methotrexate treatments were prescribed in patients without clinical or radiological improvement. Clinical and radiological progression was observed in only one case, while under cyclophosphamide treatment, in other cases, partial benefit was observed.

Table 2.

Neurosarcoidosis and medical treatment options

| Drug name | Initial dose | Side effects | Explanations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prednisone | 1 mg/kg/day, po | Osteoporosis, Cushing syndrome, hypertension, diabetes, peptic ulcus, pseudotumor cerebri, glocom, cataract, euphoria, psychosis | |

| Methylprednisolone | 1000 mg/day I.V 3 days | Very rare for 3 days treatment | |

| Methotrexate | 10–25 mg once a week po or sc | Anemia, neutropenia, hepatic dysfunction, pneumonia | Should be used combined with folic acid (1 mg day po) |

| Cyclosporine | 5 mg/day should be given in two different doses | Renal failure, hypertension | Expensive |

| Azathioprine | 50 mg, po | Anemia, neutropenia, hepatic dysfunction | Cheap |

| Cyclophosphamide | 50–200 mg po or once in 2–3 weeks 500 mg IV | Cystitis, neutropenia | Urinary function follow up in terms of microscopic hematuria |

| Hydroxylchloroquine | 200 mg/day po | Retinopathy, auto toxicity, myopathy, cardiomyopathy, neuropathy, neurophysiatric effect | Rutine eye examination with 3–6 months intervals |

| Imfliksimab | 3 mg/kg I.V 1.3.5. weeks: then once in each 6 weeks | Fever, headache, dizziness, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, myalgia, arthralgia, polyneuropathy |

IV: intravenous; po: per oral

Sarcoidosis can progress with different clinical symptomatology and radiological symptoms. Diagnosis of NS is very difficult, particularly when the initial symptoms presented with neurological involvement. Infections, such as tuberculosis, neurosyphilis, toxoplasmosis, Behçet Syndrome, lymphoma, meningeal carcinomatosis, other malignancies, and demyelinating diseases, should be considered for differential diagnosis, and detailed examinations should be performed. Although corticosteroids are believed as the first line of treatment, immunosuppressive treatments can be applied in resistant cases.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gascón-Bayarri J, Mañá J, Martínez-Yélamos S, Murillo O, Reñé R, Rubio F. Neurosarcoidosis: report of 30 cases and a literature survey. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.08.019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott TF. Neurosarcoidosis: progress and clinical aspects. Neurology. 1993;43:8–12. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.1_part_1.8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.43.1_Part_1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamzeh N. Sarcoidosis. Solunum Hastalıkları. 2010;21:104–113. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sponsler JL, Werz MA, Maciunas R, Cohen M. Neurosarcoidosis presenting with simple partial seizures and solitary enhancing mass: case reports and review of the literature. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;6:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.02.016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besur S, Bishnoi R, Talluri SK. Neurosarcoidosis: rare initial presentation with seizures and delirium. QJM. 2011;104:801–803. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcq194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delaney P. Neurologic manifestations in sarcoidosis: review of the literature, with a report of 23 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1977;87:336–345. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-87-3-336. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-87-3-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caplan L, Corbett J, Goodwin J, Thomas C, Shenker D, Schatz N. Neuro-ophthalmologic signs in the angiitic form of neurosarcoidosis. Neurology. 1983;33:1130–1135. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.9.1130. http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.33.9.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman SH, Gould DJ. Neurosarcoidosis presenting as psychosis and dementia: a case report. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2002;32:401–403. doi: 10.2190/UYUB-BHRY-L06C-MPCP. http://dx.doi.org/10.2190/UYUB-BHRY-L06C-MPCP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akova YA, Kansu T, Duman S. Pseudotumor cerebri secondary to dural sinus thrombosis in neurosarcoidosis. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1993;13:188–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krumholz A, Stern BJ, Stern EG. Clinical implications of seizures in neurosarcoidosis. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:842–844. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530200084023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Junger SS, Stern BJ, Levine SR, Sipos E, Marti-Masso JF. Intramedullary spinal sarcoidosis: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging characteristics. Neurology. 1993;43:333–337. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.333. http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.43.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayat GR, Walton TP, Smith KR, Jr, Martin DS, Manepalli AN. Solitary intra-medullary neurosarcoidosis: role of MRI in early detection. J Neuroimaging. 2001;11:66–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2001.tb00014.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6569.2001.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakaibara R, Uchiyama T, Kuwabara S, Kawaguchi N, Nemoto I, Nakata M, Hattori H. Autonomic dysreflexia due to neurogenic bladder dysfunction; anunusual presentation of spinal cord sarcoidosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:819–820. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.6.819. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.71.6.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah JR, Lewis RA. Sarcoidosis of the cauda equina mimicking Guillain-Barre syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2003;208:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00414-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-510X(02)00414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verma KK, Forman AD, Fuller GN, Dimachkie MM, Vriesendorp FJ. Cauda equina syndrome as the isolated presentation of sarcoidosis. J Neurology. 2000;247:573–574. doi: 10.1007/s004150070163. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s004150070163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uchino M, Nagao T, Harada N, Shibata I, Hamatani S, Mutou H. Neurosarcoidosis without systemic sarcoidosis-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2001;41:48–51. doi: 10.2176/nmc.41.48. http://dx.doi.org/10.2176/nmc.41.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cipri S, Gambardella G, Campolo C, Mannino R, Consoli D. Unusual clinical presentation of cerebral-isolated sarcoidosis. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Sci. 2000;44:140–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch JP., 3rd Neurosarcoidosis: how good are the diagnostic tests? J Neu-roophthalmol. 2003;23:187–189. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200309000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore FG, Andermann F, Richardson J, Tampieri D, Giaccone R. The role of MRI and nerve root biopsy in the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2001;28:349–353. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100001578. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00041327-200309000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pawate S, Moses H, Sriram S. Presentations and outcomes of neurosarcoidosis: a study of 54 cases. QJM. 2009;102:449–460. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcp042. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0317167100001578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oksanen V, Fyhrquist F, Gronhagen-Riska C, Somer H. CSF angiotensin-converting enzyme in neurosarcoidosis. Lancet. 1985;1:1050–1051. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91658-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcp042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan Seem CP, Norfolk G, Spokes EG. CSF angiotensin-converting enzyme in neurosarcoidosis. Lancet. 1985;1:456–457. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91173-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(85)91658-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juozevicius JL, Rynes RI. Increased helper/suppressor T-lymphocyte ratio in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with neurosarcoidosis. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:807–808. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-6-807. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(85)91173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferriby D, de Seze J, Stojkovic T, Hachulla E, Wallaert B, Blond S, Destée A, Hatron PY, Decoulx M, Vermersch P. Clinical manifestations and therapeutic approach in neurosarcoidosis. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2000;156:965–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zajicek JP, Scolding NJ, Foster O, Rovaris M, Evanson J, Moseley IF, Scadding JW, Thompson EJ, Chamoun V, Miller DH, McDonald WI, Mitchell D. Central nervous system sarcoidosis diagnosis and management. QJM. 1999;92:103–117. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/92.2.103. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-104-6-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells CE. The natural history of neurosarcoidosis. Proc R Soc Med. 1967;60:1172–1174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.James DG. Life-threatening situations in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1998;15:134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferriby D, de Seze J, Stojkovic T, Hachulla E, Wallaert B, Destée A, Hatron PY, Vermersch P. Long-term follow-up of neurosarcoidosis. Neurology. 2001;57:927–929. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.5.927. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/92.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen RK, Sellars RE, Sandstrom PA. A prospective study of 32 patients with neurosarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2003;20:118–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoitsma E, Faber CG, Drent M, Sharma OP. Neurosarcoidosis: a clinical dilemma. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:397–407. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00805-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.57.5.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baughman RP, Lower EE. A clinical approach to the use of methotrexate for sarcoidosis. Thorax. 1999;54:742–746. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.8.742. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00805-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agbogu BN, Stern BJ, Sewell C, Yang G. Therapeutic considerations in patients with refractory neurosarcoidosis. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:875–879. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540330053014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.54.8.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stern BJ, Schonfeld SA, Sewell C, Krumholz A, Scott P, Belendiuk G. The treatment of neurosarcoidosis with cyclosporine. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:1065–1072. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530340089023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1995.00540330053014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lower EE, Broderick JP, Brott TG, Baughman RP. Diagnosis and management of neurological sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1864–1868. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1992.00530340089023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]