Abstract

Recently, information about migraine which is generally characterized with attacks has gradually increased. In some patients with migraine, progression may be observed such that the frequency and time of the attacks are increased and an attack lasts for days. This condition is called chronic migraine (CM). According to the last classification, chronic migraine is defined as headache which occurs 15 days a month or more frequently at least 8 of which show the characteristic properties of migraine or response to migraine-specific treatment. The diagnostic cirteria of chronic migraine, its differences from other chronic daily headaches and the question if it is a migraine form with a high frequency which transforms from episodic migraine or a completely different pathophysiological picture are still contradictory. Clarifying these issues is possible with clinical studies as well as increasing the studies directed to investigate the pathophysiological mechanisms.

Keywords: Chronic migraine, headache, chronic daily headache

ÖZET

Genellikle ataklarla seyreden migren hakkında bilinenler son zamanlarda giderek artmaktadır. Bazı migrenlilerin ataklarının sıklığında, süresinde artma ve günlerce devam etmesi şeklinde progresyon olabilir ve bu durum kronik migren (KM) olarak adlandırılmaktadır. Son sınıflamaya göre; kronik migren ayda 15 gün veya daha sık ortaya çıkan ve bunların en azından 8’inin migrenin karakteristik özelliklerini taşıdığı veya migrene özgü tedaviye yanıtlı başağrısı şeklinde tanımlanmıştır. Kronik migrenin tanı ölçütleri, diğer kronik günlük başağrılarından farkları, epizodik migrenden dönüşen sık frekanslı bir migren formu mu, yoksa tamamen bağımsız bir patofizyolojik tablo mu olduğu halen tartışmalıdır. Bunların aydınlatılması, klinik çalışmaların yanı sıra patofizyolojik mekanizmaların araştırılmasına yönelik çalışmaların artması ile mümkündür.

Definition

Migraine is usually characterized with attacks and we have been provided with increased information about migraine recently (1). The persistent tendency of the patients with migraine to attacks (2, 3), abnormalities in cortical function (4) and disrupted quality of life (5) even between attacks suggest that migraine is not only an episodic condition, but a chronic disease characterized with attacks (6).

In addition, progression such as increase in the frequency and in the time periods of attacks and lasting of attacks for days may be observed in some patients. This condition is named as chronic migraine (CM). This picture for which different views have been proposed on definition and criteria for a long time is one of the areas neglected in the first classifications of migraine and could not take the place it deserves in studies for long years. It differentiation from other chronic daily headache pictures including mainly chronic tension headache is important. Although changing and developing definitions have been proposed in years in the classifications of the International Headache Society-IHS, the definition of the last classification is as follows: chronic migraine occurs 15 days a month or more frequently and at least 8 of these attacks have migrainous character or respond to migraine-specific treatment (Table 1) (7). It is important that drug overuse is questioned and excluded, if possible.

Tablo 1.

The Diagnostic Criteria of Chronic Migraine (based on IHS diagnostic criteria) (9).

| Presence of headache for 15 days a month or more for a period of longer than three months. |

| At least 8 of these should have migrainous character. |

| Headache should respond to migraine-specific treatment. |

| It should not be related with another disease. |

Triptans, serotonin 5-HT 1B/1D receptor agonists or ergotamine derivatives are accepted as migraine-specific treatment. A history of migraine without aura is present in 90% of the patients with CM. While headaches become frequent in months or years, the frequency and severity of related symptoms including photophobia, phonophobia and nausea decrease (8). Another important issue is the fact that CM was considered among migraine complications in the final classification (9). All etiologic causes should be excluded before a diagnosis of CM is made.

The issues about chronic migraine which are still being debated currently include the diagnostic criteria, if it is different from chronic daily headaches or it it is a form of migraine with a high frequency transforming from episodic migraine or a completely independent pathophysiological picture. Elucidation of these points is only possible with elucidation of the pathophysiologic mechanisms.

Epidemiology

Although the worldwide prevalence of chronic migraine changes according to different studies, it is approximately 1–3% (10,11,12). When chronic migraine is compared with episodic migraine (EM), it is generally considered a rare subtype of migraine, but it is observed more frequently compared to epilepsy and other neurological diseases (13).

According to a large population-based epidemiological study performed in our country, the prevalence of migraine is 16.4%. Approximately 10% of these patients with migraine have CM (Table 2). Chronic migraine occurs most frequently between 20 and 50 years of age (14).

Tablo 2.

The prevalence of chronic migraine and probable chronic migraine in Turkey (14).

| Female %(n) n=640 |

Male %(n) n=231 |

Total %(n) n=874 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic migraine (drug overuse absebt) | 2.7 (n=17) | 2.6 (n=6) | 2.6 (n=23) |

| Probable chronic migraine (drug overuse present) | 8.8 (n=56) | 6.5 (n=15) | 8.2 (n=71) |

| Total | 11.5 (n=73) | 9.1 (n=21) | 10.8 (n=94) |

The “American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention” study is a large study investigating the epidemiology of migraine and CM. According to this study CM was found approximately in 2% people (15). In addition, the mean age and body mass index of the patients with CM were found to be higher and the education level was found to be lower compared to the patients with EMA in this study. The rate of working full-time is 37.8% in patients with CM, while it is higher in patients with EM (%52.3). No difference was found between the two groups in terms of gender.

It has been shown that chronic migraine and EM are related with psychiatric and medical diseases. Especially, the relation of CM with comorbid diseases is stronger compared to episodic migraine. It has been observed that psychiatric and painful diseases are related with CM more frequently. In addition, the association of obesity and cardiovascular disease is more frequent in CM. The rates of other related diseases in CM and EM are given in Table 3 (16).

Tablo 3.

Co-morbid diseases and their frequencies in patients with chronic and episodic migraine. Adapted from the study ‘Buse DC et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:422–435’ (16).

| Co-morbid disease | Chronic migraine (%) | Episodic migraine (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Arthritis | 33.6 | 22.2 |

| Non-migraine chronic pain | 31.5 | 15.1 |

| Anxiety | 30.2 | 18.8 |

| Depression | 42.2 | 25.6 |

| Bipolar disease | 4.6 | 2.8 |

| Obesity | 25.5 | 21.0 |

| Circulatory problems | 17.3 | 11.4 |

| Heart disease | 9.6 | 6.3 |

| Hypertension | 33.7 | 27.8 |

| Stroke | 4.0 | 2.2 |

| Allergy | 59.9 | 50.7 |

| Asthma | 24.4 | 17.2 |

| Bronchitis | 19.2 | 12.9 |

| Chronic bronchitis | 9.2 | 4.5 |

| Emphysema or chronic obstructive lung disease | 4.9 | 2.6 |

| Sinusitis | 45.2 | 37.0 |

Chronic migraine affects social life and physical and occupational performance with a great extent (16, 17). The lives of patients with CM are affected with a higher rate compared to patients who have a lower frequency of migraine (18, 19). Because of a higher number of days with pain and higher disease load, the disability in CM is much higher compared to EM (18, 19). When the patients were evaluated by MIDAS (Migraine Disability Assessment) questionnaire (20), it was observed that the mean score was higher in patients with CM compared to EM and the disability was observed to be 2-fold higher (CM: 20%, EM: 11.1%) (13, 21).

It has been observed that chronic migraine develops in approximately 2.5–3% of the patients with episodic migraine (22, 23). Risk factors for chronic migraine have been defined as low socioeconomical status, obesity, snoring, comorbid pain, neck and head trauma, stressful events, high caffeine intake, overusse of analgesic drugs, anxiety, depression and allodynia (22, 24).

Especially the relation between drug overuse headache and CM is similar to chicken-egg relation and it is not clear which one is the inititating factor in many cases. In cases of idiopathic intracranial hypertension without papilledema, intracranial hypotension and chronic meningitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Therefore, it is very important to perform lumbar puncture and examine the cerebrospinal fluid when there is no typical history of transformation.

Patophysiology and Complications

The progression of migraine occurs at the clinical, functional and anatomic level. Increase in the frequency of attacks, change in the type of the pain and development of disability constitute the clinical changes. Physiological progression includes changes in the nosciceptive threshold (allodynia) and pain pathway (central sensitization). In addition, progression may include persistent anatomical changes (25). In an imaging study, accumulation of iron was shown in the periaquaductal grey area (PGA) in patients with frequent headaches. PGA is related with descending analgesic pathway, is important in endogeneous analgesia and pain control and is closely related with trigeminal nucleus caudalis. It is thought that there is disruption in iron homeostasis in PGA in patients with chronic migraine (26).

In approximately 75% of the patients with migraine, central sensitization develops during migraine attacks. Central sensitization is cutaneous allodynia which occurs as a result of sensitization of the trigeminal neuron (27). In population-based studies, a direct relation was shown between presence of cutaneous allodynia and the frequency, severity and disability of migraine. Cutaneous allodynia is more prominent in patients with EM compared to patients with CM (28). Central sensitization may play a role in progression of the disease. It is thought that recurrent central sensitization episodes may be related with persistent neuronal demage at the level of the PGA or around the PGA (28, 29).

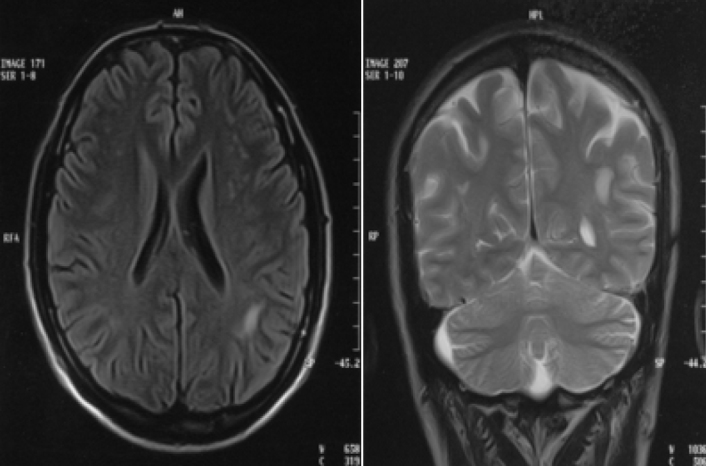

It is known that some nonspecific white matter changes detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be present in patients with migraine independent of age and vascular risk factors (30) (Şekil 1). It has been shown that the possibility of detecting deep white matter lesion is high in men with migraine with aura and in women with migraine with and without aura. In addition, it has been found that the amount of white matter lesions was directly proportional to the frequency of attacks (31). The nature of these lesions and the issues if they are ischemic or metabolic or if they are persistent or transient are still not known.

The relation between migraine (especially migraine with aura) and stroke has been known for a long time. Migraine with aura is a rsik factor for subclinical ischemic lesions in the posterior system and brain stem. Supratentorial lesions have also been shown in individuals who have infratentorial lesion. It has been thought that this was caused by the hemodynamical changes during migraine attacks (31). No significant increase in possible ischemic risks for CM has been noted. In addition, migraine is also a rsik factor for cardiovascular diseases. The risk of angina, myocardial ischemia and the mortality related with cardiovascular events is higher in patients with migraine with aura (32).

Conclusively, it is thought that migraine progression occurs by triggering of migraine attacks by the underlying mechanisms or some dysfunctions with an increase in the frequency of the attacks.

Treatment

Preventive treatment should be administered in all patients with chronic migraine, but it has been shown that only 3–13% of the patients used prophylactic drugs in population-based studies (22). Preventive treatment renders acute attack treatment more efficicent (33).

The drugs used in treatment of chronic migraine are the same drugs used in migraine prophylaxis. These include beta-blockers which are used in hypertension and cardiac rhythm disorders (propranolol, metoprolol, nebivolol), calcium channel blockers (verapamil, flunarizine), epilepsy drugs (valproic acid, topiramate, gabapentin, etc.), antidepressants (amitryptiline, venlafaxine, serotonin reuptake inhibitors), pizotifen ve memantine.

Currently, topiramate is one of the most commonly used drugs in treatment of CM. It has multiple mechanisms of action including GABA-A receptors, sodium channels, glutamate receptor antagonism, carbonic anhydrase, protein kinase inhibition, serotonin activity or possible neuroinflammatory factors. Topiramate was shown to have the same efficiency even without detoxification in patients with drug overuse who continued to receive acute attack treatment (34, 35).

Onabotulinumtoxin A (BTX) is a neurotoxin which blocks release of presynaptic acetylcholine irreversibly. It has been proposed that the mechanism of action includes inhibition of release of the neurotransmitters including P substance and calcitonin and impact on muscle spasm and nerve transduction (36, 37). BTX prevents progression of central sensitivity by inhibiting peripheral sensitivity (38, 39). In the PREEMPT study in which the efficiency of BTX in CM was shown, onabotulinumtoxin A or placebo was administered to 679 and 705 patients every 12 weeks for 32 weeks. The BTX groups was found to be moderately superior to the placebo group in terms of decrease in the number of days with headache, decrease in the severity of pain, disability and the number of days in which triptane was used (absolute benefit: 6.7% and 11% in PREEMPT 1 and 2, respectively) (40). The same efficiency was observed in CM both in the patients who used 100–200 mg/day topiramate and in the patients who used maximum 200 units BTX. In addition, fewer side effects were observed in the patients who received BTX (41).

Gabapentin and Pregabalin were shown to be partially effective in treatment of CM (42, 43).

Tizanidin is a muscle relaxants and alpha2-adrenergic agonist. It was shown to be effective in chronic headache compared to placebo when administered at a dose of 24 mg/day. It is usually used as adjuvant treatment. Its side effects include somnolance, dry mouth, malaise and fainting (44).

Fluoxetine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. When is is administered as a dose of 40 mg/day, it was shown to be beneficial 3 months later in patients with chronic headache (45).

Zonisamide was also shown to be partially efficient a long time after administration of a mean dose of 337.9 mg in patients with resistant migraine (46).

Memantine (MEM) is a glutamergic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist. When it is given at a dose of 10–20 mg/day to patients in whom at least one of the standard migraine prevention therapies was ineffective, a decrease of approximately 50% in the number of days with migraine and a dicrease in disability was found after 3 months. The most common side effects include somnolance, asthenia and mood changes. It can be used in individuals who do not benefit from traditional treatment (47, 48).

A multiple approach is needed in treatment of chronic migraine. Education, social support, optimization of the level of expectation, close monitoring and life style adjustments (sleep, diet, alcohol, coffee, etc.) are important. Behavioral strategies in addition to determining and preventing triggering factors are considered. Psychiatric evaluation is valuable in many cases.

Figure 1.

White matter changes with unclear etiology observed in MRI of a patient with chronic migraine.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors reported no conflict of interest related to this article.

Çıkar çatışması: Yazarlar bu makale ile ilgili olarak herhangi bir çıkar çatışması bildirmemişlerdir.

References

- 1.Charles A. The evolution of a migraine attack - a review of recent evidence. Headache. 2013;53:413–419. doi: 10.1111/head.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gantenbein AR, Sandor PS. Physiological parameters as biomarkers of migraine. Headache. 2006;46:1069–1074. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambrosini A, Rossi P, De Pasqua V, Pierelli F, Schoenen J. Lack of habituation causes high intensity dependence of auditory evoked cortical potentials in migraine. Brain. 2003;126:2009–2015. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granziera C, DaSilva AF, Snyder J, Tuch DS, Hadjikhani N. Anatomical alterations of the visual motion processing network in migraine with and without aura. PLoS Med. 2006;3:1915–1921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipton RB, Hamelsky SW, Kolodner KB, Steiner TJ, Stewart WF. Migraine, quality of life, and depression: A population-based case-control study. Neurology. 2000;55:629–635. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.5.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haut SR, Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Chronic disorders with episodic manifestations: Focus on epilepsy and migraine. Lancet Neurology. 2006;5:148–157. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70348-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Headache Classification Committee. Olesen J, Bousser MG, Diener HC, Dodick D, First M, Goadsby PJ, Göbel H, Lainez MJ, Lance JW, Lipton RB, Nappi G, Sakai F, Schoenen J, Silberstein SD, Steiner TJ. New appendix criteria open for a broader concept of chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:742–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ. Headache in Clinical Practice. Second Edition. ISISs Medical Media; Oxford: 2002. pp. 102–103. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):9–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Natoli JL, Manack A, Dean B, Butler Q, Turkel CC, Stovner L, Lipton RB. Global prevalence of chronic migraine: A systematic review. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:599–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castillo J, Muñoz P, Guitera V, Pascual J. Epidemiology of chronic daily headache in the general population. Headache. 1999;39:190–196. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1999.3903190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scher AI, Stewart WF, Liberman J, Lipton RB. Prevalence of frequent headache in a population sample. Headache. 1998;38:497–506. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1998.3807497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipton RB. Chronic migraine, classification, differential diagnosis, and epidemiology. Headache. 2011;2:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ertas M, Baykan B, Kocasoy Orhan E, Zarifoglu M, Karlı N, Saip S, Onal AE, Siva A. One-year prevalence and the impact of migraine and tension-type headache in Turkey: a nationwide home-based study in adults. J Headache Pain. 2012;13:147–157. doi: 10.1007/s10194-011-0414-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF AMPP Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343–349. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buse DC, Rupnow MF, Lipton RB. Assessing and managing all aspects of migraine: migraine attacks, migraine-related functional impairment, common comorbidities, and quality of life. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:422–435. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60561-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, Buse DC, Kawata AK, Manack A, Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB. Results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS) Cephalalgia. 2011;31:301–315. doi: 10.1177/0333102410381145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buse DC, Manack A, Serrano D, Turkel C, Lipton RB. Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:428–432. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.192492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bigal ME, Serrano D, Reed M, Lipton RB. Chronic migraine in the population: burden, diagnosis, and satisfaction with treatment. Neurology. 2008;71:559–566. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000323925.29520.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Sawyer J, Edmeads JG. Clinical utility of an instrument assessing migraine disability: The migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire. Headache. 2001;41:854–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Stewart WF. Clinical trials of acute treatments for migraine including multiple attack studies of pain, disability, and healthrelated quality of life. Neurology. 2005;65:50–58. doi: 10.1212/wnl.65.12_suppl_4.s50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bigal ME, Serrano D, Buse D, Scher A, Stewart WF, Lipton RB. Acute migraine medications and evolution from episodic to chronic migraine: a longitudinal population-based study. Headache. 2008;48:1157–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scher AI, Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Lipton RB. Factors associated with the onset and remission of chronic daily headache in a population-based study. Pain. 2003;106:81–89. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scher AI, Midgette LA, Lipton RB. Risk factors for headache chronification. Headache. 2008;48:16–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Concepts and mechanisms of migraine chronification. Headache. 2008;48:7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welch KMA, Nagesh V, Aurora SK, Gelman N. Periaquaductal gray matter dysfunction in migraine: Cause or the burden of illness? Headache. 2001;41:629–637. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burstein R, Yarnitsky D, Goor-Aryeh I, Ransil BJ, Bajwa ZH. An association between migraine and cutaneous allodynia. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:614–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bigal ME, Ashina S, Burstein R, Reed ML, Buse D, Serrano D, Lipton RB AMPP Group. Prevalence and characteristics of allodynia in headache sufferers. Neurology. 2008;70:1525–1533. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310645.31020.b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burstein R, Jakubowski M. Analgesic triptan action in an animal model of intracranial pain: A race against the development of central sensitization. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:27–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.10785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter A, Gladstone JP, Dodick DW. Migraine and white matter hyperintensities. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2005;9:289–293. doi: 10.1007/s11916-005-0039-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kruit MC, van Buchem MA, Hofman PA, Bakkers JT, Terwindt GM, Ferrari MD, Launer LJ. Migraine as a risk factor for subclinical brain lesions. JAMA. 2004;291:427–434. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Cook NR, Logroscino G, Diener HC, Buring JE. Migraine and risk of cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA. 2006;296:283–291. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bermejo PE, Dorado R, Gomez-Arguelles JM. Variation in almotriptan effectiveness according to different prophylactic treatments. Headache. 2009;49:1277–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Limmroth V, Biondi D, Pfeil J, Schwalen S. Topiramate in patients with episodic migraine: reducing the risk for chronic forms of headache. Headache. 2007;47:13–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diener HC, Dodick DW, Goadsby PJ, Bigal ME, Bussone G, Silberstein SD, Mathew N, Ascher S, Morein J, Hulihan JF, Biondi DM, Greenberg SJ. Utility of topiramate for the treatment of patients with chronic migraine in the presence or absence of acute medication overuse. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:1021–1027. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aoki KR. Review of a proposed mechanism for the antinociceptive action of botulinum toxin type A. Neurotoxicology. 2005;26:785–793. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aoki KR. Evidence for antinociceptive activity of botulinum toxin type A in pain management. Headache. 2003;43:9–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.43.7s.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silberstein SD, Stark SR, Lucas SM, Christie SN, Degryse RE, Turkel CC BoNTA-039 Study Group. Botulinum toxin type A for the prophylactic treatment of chronic daily headache: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1126–1137. doi: 10.4065/80.9.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oshinsky ML, Pozo-Rosich P, Luo J. Botulinum toxin type A blocks sensitization of neurons in the trigeminal nucleus caudalis. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:781. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diener HC, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, Lipton RB, Silberstein SD, Brin MF PREEMPT 2 Chronic Migraine Study Group. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:804–814. doi: 10.1177/0333102410364677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mathew N, Jaffri S. A double-blind comparison of Onabotulinumtoxin A (BOTOX) and topiramate (topamax) for the prophylactic treatment of chronic migraine: a pilot study. Headache. 2009;49:1466–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathew NT, Rapoport A, Saper J, Magnus L, Klapper J, Ramadan N, Stacey B, Tepper S. Efficacy of gabapentin in migraine prophylaxis. Headache. 2001;41:119–128. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.111006119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calandre EP, Garcia-Leiva JM, Rico-Villademoros F, Vilchez JS, Rodriguez-Lopez CM. Pregabalin in the treatment of chronic migraine: an open-label study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33:35–39. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181bf1dbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saper JR, Lake AE, 3rd, Cantrell DT, Winner PK, White JR. Chronic daily headache prophylaxis with tizanidine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter outcome study. Headache. 2002;42:470–482. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saper JR, Silberstein SD, Lake AE, 3rd, Winters ME. Double-blind trial of fluoxetine: chronic daily headache and migraine. Headache. 1994;34:497–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1994.hed3409497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ashkenazi A, Benlifer A, Korenblit J, Silberstein SD. Zonisamide for migraine prophylaxis in refractory patients. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:1199–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramadan NM. The link between glutamate and migraine. CNS Spectr. 2003;8:446–449. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900018757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bigal M, Rapoport A, Sheftell F, Tepper D, Tepper S. Memantine in the Preventive Treatment of Refractory Migraine. Headache. 2008;48:1337–1342. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]