Abstract

Introduction

Olfactory dysfunction is an early and common symptom in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (IPD). Recently, the relation between olfactory dysfunction and cognitive loss in IPD has been reported. In our study, we aimed to investigate the relation between olfactory dysfunction and cognitive impairments in early IPD related with this theory.

Methods

In this study, we included 28 patients with stage 1 and stage 2 IPD according to the Hoehn-Yahr (H-Y) scale and 19 healthy participants. The University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) was performed for evaluating olfactory function. For cognitive investigation in participants, the clock drawing test, Stroop test, verbal fluency test, Benton face recognition test (BFR), Benton line judgment orientation test (BLO), and Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) were performed.

Results

We found significantly lower UPSIT scores in the patient group compared to controls (p=.018). In the neuropsychological investigation, only Stroop test and BLOT test scores were significantly lower in the patient group compared to controls (p=.003, p=.002, respectively). We found a negative correlation between UPSIT scores and Stroop time (p=.033) and Stroop error (p=.037) and a positive correlation between UPSIT scores and SBST long-term memory scores (p=.016) in patients.

Conclusion

In our study, we found mild cognitive impairment related with visuospatial and executive functions in early-stage IPD compared to controls. But, in the patient group, we detected a different impairment pattern of memory and frontal functions that correlated with hyposmia. This different pattern might be indicating a subgroup of IPD characterized by low performance in episodic verbal memory, with accompanying olfactory dysfunction in the early stage.

Keywords: Olfactory dysfunction, Parkinson disease, cognition

Introduction

Olfactory dysfunction is one of the most common non-motor symptoms in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (IPD). Olfactory loss is present at the earliest stages of the disease (1). Stephanson et al. (2) indicated that olfactory dysfunction may be an early predictor of abnormal cognitive impairments and implicated a special phenotypic pattern.

Changes in cognitive functions occur in IPD as non-motor symptoms. These changes were reported as executive functions, visuospatial functions, and disturbance in working memory. Memory is more spared or secondarily affected by the preservation of recognition (3,4). But, previously, Bohnen et al. and then Postuma and Gagnon reported a relation between olfactory loss and memory dysfunction in IPD (5,6). In the following studies, a relation with olfactory dysfunction in IPD and impairment of memory, executive functions, and verbal functions has been reported (7,8). According to this relation, olfactory dysfunction is associated with cholinergic dysfunction and supposed to be an early marker of a phenotype with cognitive and non-motor symptom dominance in IPD (9). But, all of these studies were investigated in moderate-stage patients. In our study, we tried to evaluate a clinical approach according to this theory in the early stages in two different ways. First, we compared patterns of cognitive dysfunction between patients with IPD and controls. Then, in the same group, we evaluated whether cognitive functions related with olfactory dysfunction have a different pattern related to early cholinergic impairment, as proposed.

Method

This study was performed at the movement disorders outpatient clinic of the Department of Neurology Haseki Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey. The study was approved by the local ethical committee, and all of the patients gave written informed consent before being included into the study; 28 patients (5 females/23 males) were enrolled into the study. All patients were diagnosed with IPD according to the United Kingdom Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank diagnostic criteria (10).

The control group was selected from 19 healthy cases (8 females/11 males) without any neurological and olfactory pathologies or family history of neurodegenerative disease. We evaluated the Hoehn-Yahr Scale (H-Y) for disease staging and the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) to establish clinical severity (11). According to H-Y, 10 patients in stage 1 (1 female/9 males) and 18 patients in stage 2 (4 females/14 males) were included.

Patients with dementia were not recruited into the study. Dementia was diagnosed according to the Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Dementia Associated with Parkinson’s Disease (12).

Olfactory Function

Individuals were inspected and excluded if they had other problems that can cause olfactory dysfunction, like head trauma, nasal polyposis, allergic rhinitis, and severe septal deviation, at the Department of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery in our hospital. The University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) was used to all of the individuals (13).

Cognitive Assessments

Global cognitive function was assessed using the Turkish version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (14). Verbal memory was assessed by a Turkish verbal learning test, the Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT). This test evaluates the learning of a full list of 15 words after a maximum 10 trials (total learning score) and recall after a 30-minute delay, followed by a free-recall trial (delayed recall) (15). For the assessment of executive functions, a group of tests, consisting of the Stroop Color Word Test (SCWT), clock drawing test, and Categorical Verbal fluency test, were used. For the Stroop test, an edited and modified Turkish version (TUBİTAK-BİLNOT) was used (16,17,18).

To assess visual perceptive functions, the short form of the Benton’s face recognition test (BFR) (short form) and Benton line judgment orientation test (BLOT) were used. For the BLOT and BFR, edited and modified Turkish versions (TUBİTAK-BİLNOT) were used (16).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Number Cruncher Statistical System (NCSS) 2007& Power Analysis and Sample Size (PASS) 2008 Statistical Software (Utah, USA) program. Quantitative data were given as mean±standard deviation (SD), and categorical data were given as percentages. One-way ANOVA test for comparison of normally distributed parameters between groups and Tukey HSD test for detecting which group differed were used. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine significant differences in non-normally distributed parameters. Mann-Whitney U-test was used to determine differences between the groups if a significant difference was found in the Kruskal-Wallis test. For comparisons between two groups in normally distributed parameters, student t-test was performed, and for non-normally distributed parameters, Mann-Whitney U-test was performed. χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Confidence intervals were computed at the 95% level. A p value below 0.05 was accepted as significant.

To analyze the correlation between olfactory dysfunction and cognitive tests and disease properties, Pearson test or Spearman’s rho test was used when appropriate.

Results

The demographic and clinical properties of the Stage 1, Stage 2, and control groups are shown in Table 1. Only age was significantly different among the groups according to the one-way ANOVA test (p<.01). Post hoc Tukey HSD test demonstrated that the patients in the Stage 2 group were significantly older than both the Stage 1 and control groups (p=.004, p=.044, respectively). We found a statistically significant difference among the groups for olfactory test scores (p<.01). According to the post hoc Tukey HSD test, UPSIT scores were significantly lower in both the Stage 1 and 2 groups compared with the control group (p=.018 and p=.003, respectively). There was no significant difference between the Stage 1 and Stage 2 groups for UPSIT scores (p=.923). We found no significant difference in cognitive state evaluated by MMSE.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographical properties of Stage 1, Stage 2 and control groups

| Stage 1 N=10 |

Stage 2 N=18 |

Control N=19 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 59.60±7.04 | 67.94±6.05 | 62.84±6.01 | .004 |

| Gender (F/M)x | 1/9 | 4/14 | 8/11 | .149 |

| Disease duration (month) | 44.80± | 41.54 | 47.11±42.13 | --- |

| UPSIT | 15.6 ±5.18 | 15.33 ±4.52 | 21.05± 5.08 | .002 |

| UPDRS motor | 9.60±1.83 | 11.44±1.72 | --- | .013 |

| MMSE | 26.70±1.70 | 25.89±2.05 | 27.15±.16 | .078 |

Oneway ANOVA (p<0.05),

Chi-square test,

F: Female, M: Male, UPSIT: University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test, UPDRS: Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination

Student t-test for clinical properties (UPDRS motor) and Mann-Whitney U-test for disease duration were used for comparisons between the Stage 1 and Stage 2 groups. UPDRS motor scores were significantly higher in the Stage 2 group (p=.013). There was no significant difference for disease duration between the Stage 1 and Stage 2 groups (p>.05).

We found no significant difference among the control, Stage 1, and Stage 2 groups for clock drawing test, verbal fluency test, and Stroop test scores for evaluating executive functions (Table 2). In contrast, there was a significant difference in Stroop test time scores among the control, Stage 1, and Stage 2 groups (p=.003). Time scores were significantly lower in the control group compared to the Stage 1 and Stage 2 groups using post hoc Tukey HSD test (p=.004; p=.027) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Neurocognitive test scores of Stage 1, Stage 2 and control groups

| Stage 1 N=10 |

Stage 2 N=18 |

Control N=19 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clock drawing | 8.9±0.87 | 8.05±1.47 | 8.73±1.09 | .136 |

| STROOP timex | 59.06±14.20 | 53.72±15.48 | 42.21±9.41 | .003 |

| STROOP Error | 1.90±1.85 (1.5) | 1.72±1.90 (1) | .84±.89 (1) | .208 |

| Verbal Fluency | 25.10±7.47 | 22.17±4.65 | 23.95±3.55 | .302 |

| BLOT | 20.30±2.67 | 13.39±9.21 | 20.42±2.73 | .002 |

| BFR | 42.50±2.87 | 40.72±2.88 | 42.10±3.44 | .266 |

| AVLT-total | 110.50±9.83 | 105.57±12.12 | 111.79±7.9 | .176 |

| AVLT-delayed recall | 8.70±2.62 | 8.22±2.46 | 9.68±1.85 | .152 |

Oneway ANOVA (p<0.05),

Kruskal Wallis test,

BLOT: Benton Line Judgement Orientation Test, BFR: Benton Face Recognition Test, AVLT: Auditory Verbal Learning Test

In the evaluation of the visuospatial functions, we found a significant difference in the BLOT scores among the three groups (p<.05). BLOT scores were significantly lower in the Stage 2 group compared to the control and Stage 1 groups according to post hoc Tukey HSD test (p=.017, p.003, respectively). BFR results were not significantly different among the groups (p>.05) (Table 2). We did not find any significant difference in the verbal memory scores among the control and Stage 1 and Stage 2 groups (p>0.05) (Table 2).

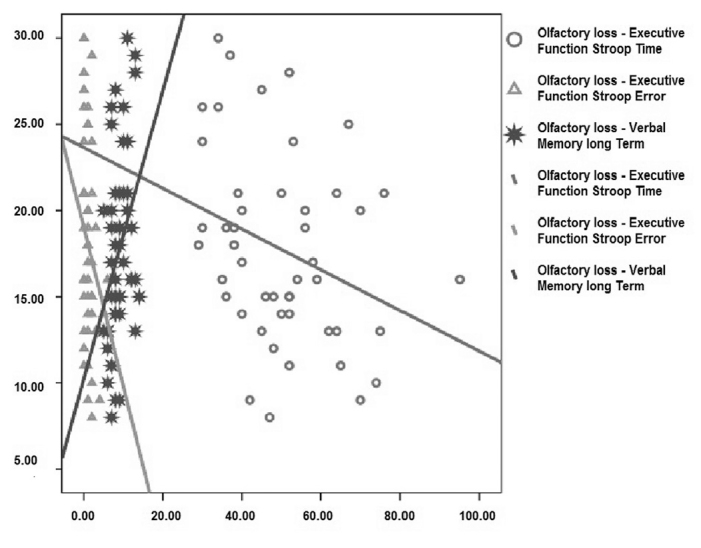

We evaluated the relation of UPSIT scores with the neuropsychometric test profiles of IPD patients. Our evaluation revealed a correlation between low odor scores and some executive tests and low verbal memory test scores. Such a relation was not observed for tests associated with visuospatial functions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation coefficiency between UPSIT scores and cognitive functions and clinical properties

| UPSIT | ||

|---|---|---|

| R | P | |

| MMSE | .050 | .739 |

| Clock drawing | .277 | .060 |

| STROOP Time | −.311 | .033* |

| dSTROOP Error | −.305 | .037* |

| Verbal Fluency | .184 | .215 |

| BLOT | .098 | .511 |

| BFR | .110 | .462 |

| AVLT-Total | .200 | .179 |

| AVLT-Delayed recall | .349 | .016* |

| Age | .066 | .660 |

| UPDRS- Motor | .124 | .529 |

| dDisease duration | −.171 | .386 |

Pearson Correlation Analyse

Spearman’s Rho correlation analyse

p<0.05

UPSİT: University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test, MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination, BLOT: Benton Line Judgement Orientation Test, BFR: Benton Face Recognition Testi, AVLT: Auditory Verbal Learning Test, UPDRS: Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale

In addition, there was no relation between olfactory disorder and the duration of the disease and motor parameters measured by UPDRS motor scores.

A negative correlation was found between the UPSIT scores and Stroop time scores of executive functions (31.1%) and between UPSIT scores and Stroop error scores (30.5%) (Table 3). While there was no significant correlation between the AVLT total learning and UPSIT scores (p>.05), AVLT delayed recall scores and UPSIT results were found to correlate positively (34.9%) (p<0.05) (Table 3).

Discussion

It is known that impairment in cognitive functions is common in early IPD (3). The pattern of this impairment is usually observed in executive and visuospatial functions and also working memory (4,19). Memory is relatively affected. Recognition is preserved. The effect of this impairment on memory is seen in the recall stage (3). Likewise, it has been observed that in the sampling group of this study, compared to healthy subjects, patients at the early stages exhibited low performance in executive and visuospatial tests in the neuropsychological evaluation without overall cognitive deterioration. These findings are consistent with classical knowledge.

Recently, this cognitive impairment, monitored at the early stages of IPD, has come to be evaluated within the general concept of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which aims to highlight development from a mild impairment to dementia in stages; this impairment follows a pattern of progression similar to those observed in other degenerative dementias. According to this approach, in a recent study by Aarsland et al., it was found that memory impairment is the most commonly observed impairment domain (13.3%), followed by impairment in visuospatial (11.0%) and attentional/executive functions (10.1%) (20,21). Moreover, the memory impairment is patterned in such a way that it includes coding/encoding impairment. The authors have indicated that the memory impairment in IPD is related to partially impaired attentional and cognitive functions and that even when the attentional/executive impairment is statistically improved, a pure memory impairment still exists. The authors also discussed whether the memory impairment observed is an impairment in encoding or recalling. Nevertheless, they have stated that they have not been able to distinguish between the two, due to the method that they used (22). In addition to this, in a couple of older studies, episodic verbal memory impairment was reported in IPD. Weintraub et al. have identified episodic verbal memory impairment in IPD patients. The authors claimed that memory impairment was overlooked and that this impairment emerged in a mixed physiopathology, including the involvement of subcortical, frontal, limbic, and temporoparietal structures (23). Whittington et al. (24), in IPD patients in the late stages of the disease, reported obvious encoding memory impairments. In their review study focusing on cognitive impairment in the early stages of IPD without dementia, Watson and Leverenz suggest that there might be a subgroup exhibiting isolated memory impairment in IPD and that this subgroup could be denoting diverse neuropathologic processes (25).

At this point, in order to shed light on the issue, it might be worthwhile to review the data on the relationship between olfactory and memory impairment in IPD. There are several studies examining this relationship. In a cohort study analyzing a group of IPD patients, Postuma and Gagnon identified a significant correlation between episodic verbal memory and olfactory impairment (6). Bohnen et al. (5) also found that there is a correlation between impaired olfactory function and poor episodic verbal memory scores. Morley et al. (7) have reported that there is a significant correlation between smell impairment and poor performance in Hopkins verbal learning tests. There is also a correlation between each test performance and the stage of the disease, in that the average H-Y score of each group is above 2. Damholdt et al. (8) found that anosmic IPD patients displayed poorer composite memory scores compared to both nonanosmic and control group.

The common point of these studies with different patterns is that there is a correlation between olfactory impairment observed at the early stage of IPD and poor episodic verbal memory scores (5,6,7,8). This finding is consistent with the findings of our study. As indicated in a review study by Morley and Duda, these findings could be an indicator of a specific cognitive domain accompanying olfactory impairment (26). Similar to the one in our study, in Morley’s study, this memory impairment, correlating with smell impairment, is also accompanied by a special impairment pattern related to executive functions (8). Unlike these studies, olfactory impairment was accompanied by low MMSE scores in the study of Bohnen et al. and by nonverbal memory impairment in the study of Postuma and Gagnon (5,6). This study has further contributed to the field by indicating that this finding is common, even in patients in the early stages (H-Y 1–2). The reason for this is that all other studies have been conducted on diverse patients and in those in relatively later stages (H-Y>2) but still without dementia (5,6,7,8,9). The reason that different studies implicate different cognitive domain impairments (except for the episodic verbal memory impairments) correlating with olfactory dysfunction could be the consequence of having examined relatively different stages of IPD patients in these studies.

In IPD, pathological changes related to both Alzheimer and Parkinson’s diseases are observed in the hippocampus and temporoparietal cortex (3). In their study conducted on IPD patients at the early stage and not taking medication, Brück et al. (27) found that when compared to healthy controls, IPD patients had atrophy in the hippocampus, in addition to the prefrontal cortex. They also identified a correlation between left hippocampal atrophy and verbal memory functions. Although cholinergic denervation and cholinergic damage in Meynert’s basal nucleus are typical findings of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), in vivo neuroimaging studies have shown that damage is also observed in Parkinsonian dementia, as much as it is observed in AD (28).

Bohnen et al. (29) first claimed that olfactory impairment is associated with hippocampal dopaminergic denervation. However, in their later studies, they claimed that smell impairment might not be related to the dopaminergic system in IPD patients and that in these patients, central cholinergic is affected, rather than functional imaging and dopaminergic (5,9).

These data are interpreted in two ways in terms of the underlying physiopathological processes. According to the first interpretation, as highlighted in Bohnen’s study, it is believed that these findings are seen in the very early stages in patients with AD pathology and combined pathologies (9). These patients are likely to progress towards dementia, exhibiting early consolidation impairment, as well as impairments, probably in the cholinergic mechanism accompanied by limbic impairment. In a study conducted by Stephenson (2), after a follow-up period of 2–6 years, IPD patients that did not initially have dementia started to exhibit olfactory impairment and visual hallucinations and developed dementia. A recently published study by Baba has also yielded results supporting this interpretation. In this study, 44 IPD patients who did not have dementia in the beginning but had severe hyposmia were tracked for 3 years. After tracking, it was observed that 10 of the patients developed dementia (30).

The second interpretation asserts that starting from the early stage, in IPD, there can be a subgroup with diverse neuropathologic characteristics. The views of Postoma and Gagnon also support this interpretation (6). Morley and Duda asserted that for IPD, olfactory impairment is an early and a premotor biomarker that can be used in the diagnosis and prediction of a clinical phenotype (26). As a matter of fact, these interpretations can be considered as following or complementing each other. A distinct phenotype resulting from episodic memory impairment and olfactory impairment in the early stage can lead to a more advanced level of dementia through the physiopathological mechanisms mentioned above in the later stages of the disease. However, more studies need to be conducted on these physiopathological mechanisms.

In this study, the comparison of early-stage IPD patients with healthy controls in terms of cognitive functions has shown that there is a mild cognitive impairment pattern in IPD that is related to the visuospatial and frontal axis. This finding is consistent with the cognitive impairment pattern indicated in early-stage PD in previous studies. However, in the statistical analysis of the relationship between hyposmia and cognitive functions in the patient group, it was found that low performance in episodic verbal memory and frontal functions is associated with hyposmia. This cognitive pattern is different from the pattern pertaining to the general group. This situation may be related to the existence of a distinct phenotype in IPD. This finding may further clinically help explain the neurotransmitter roots of cognitive impairments observed in IPD patients with hyposmia in the early stage of the disease.

Figure 1.

Cognitive functions correlating with olfactory dysfunctions

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors reported no conflict of interest related to this article.

References

- 1.Haehner A, Hummel T, Reichmann H. Olfactory dysfunction as a diagnostic marker for Parkinson’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1773–1779. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/ern.09.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephenson R, Houghton D, Sundarararjan S, Doty RL, Stern M, Xie SX, et al. Odor identification deficits are associated with increased risk of neuropsychiatric complications in Patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2099–2104. doi: 10.1002/mds.23234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.23234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emre M. What causes mental dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease? Mov Disord. 2003;18:63–71. doi: 10.1002/mds.10565. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.10565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrer I. Neuropathology and neurochemistry of nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2011;708404:1–13. doi: 10.4061/2011/708404. http://dx.doi.org/10.4061/2011/708404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohnen NI, Muller ML, Kotagal V, Koeppe RA, Kilbourn MA, Albin RL, Frey KA. Olfactory dysfunction, central cholinergic integrity and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2010;133:1747–1754. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq079. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Postuma R, Gagnon JF. Cognition and olfaction in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2010;133:1–2. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morley JF, Weintraub D, Mamikonyan E, Moberg PJ, Siderowf AD, Duda CE. Olfactory dysfunction is associated with neuropsychiatric manifestations in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26:2051–2057. doi: 10.1002/mds.23792. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.23792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damholdt MF, Borghammer P, Larsen L, Østergaard K. Odor identification deficits identify Parkinson’s disease patients with poor cognitive performance. Mov Disord. 2011;26:2045–2050. doi: 10.1002/mds.23782. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.23782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohnen NI, Muller ML, Kotagal V, Koeppe RA, Kilbourn MA, Albin RL, Frey KA. Replay: Cognition and olfaction in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2010;133:1747–1754. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq079. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniel SE, Lees AJ. Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank, London: overview and research. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1993;39:165–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang AET, Fahn S. Assessment of Parkinson’s disease in quantification of neurological deficit. In: Munsat TL, editor. Quantification of Neurologic Deficit. Boston: Butterworts; 1989. pp. 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emre M, Aarsland D, Brown R, Burn DJ, Duyckaerts C, Mizuno Y, Broe GA, Cummings J, Dickson DW, Gauthier S, Goldman J, Goetz C, Korczyn A, Lees A, Levy R, Litvan I, McKeith I, Olanow W, Poewe W, Quinn N, Sampaio C, Tolosa E, Dubois B. Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Dementia Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1689–1707. doi: 10.1002/mds.21507. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.21507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M. Development of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: a standardized microencapsulated test of olfactory function. Physiol Behav. 1984;32:489–502. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90269-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0031-9384%2884%2990269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Güngen C, Ertan T, Eker E, Yaşar R, Engin F. Reliability and validity of the standardized Mini Mental Test Examination in the diagnosis of mild dementia in Turkish population. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2002;13:273–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Öktem Ö. Öktem sözel bellek süreçleri testi (Öktem SBST) Elkitabı. Ankara: Türk psikologlar derneği yayınları; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karakaş S. BİLNOT Bataryası El Kitabı: Nöropsikolojik Testler için Araştırma ve Geliştirme Çalışmaları. 2. Baskı. Ankara: Eryılmaz Offset Matbaacılık Gazetecilik; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker DM, Crawford J. Assessment of frontal lobe dysfunction. In: Crawford JR, Parker DM, McKinlay WW, editors. A handbook of neuropsychological assessment. Hove, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992. pp. 267–291. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brodaty H, Moore C. The clock drawing test dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: a comparison of three scoring methods in a memory disorder clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12:619–627. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/%28SICI%291099-1166%28199706%2912:6%3C619::AID-GPS554%3E3.0.CO%3B2-H. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulisevsky J, Pagonbarraga J, Pascual-Sedano B, Garcıa Sanchez C, Gironell A. Prevalence and correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Parkinson’s disease without dementia. Mov Disord. 2008;23:1889–1896. doi: 10.1002/mds.22246. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.22246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kehagia AA, Barker RA, Robbins TW. Neuropsychological and clinical heterogeneity of cognitive impairment and dementia in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:1200–1213. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70212-X. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422%2810%2970212-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aarsland D, Bronnick K, Fladby T. Mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Neurol Neuroscienci Rep. 2011;11:371–378. doi: 10.1007/s11910-011-0203-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11910-011-0203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aarsland D, Bronnick K, Williams-Gray C, Weintraub D, Marder K, Kulisevsky J, Burn D, Barone P, Pagonabarraga J, Allcock L, Santangelo G, Foltynie T, Janvin C, Larsen JP, Barker RA, Emre M. Mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease: a multicenter pooled analysis. Neurology. 2010;75:1062–1069. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f39d0e. http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f39d0e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weintraub D, Moberg P, Culbertson WC, Duda J, Stern M. Evidence for impaired encoding and retrieval memory profiles in Parkinson disease. Cog Behav Neurol. 2004;17:195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whittington CJ, Podd J, Stewart-Williams S. Memory deficits in Parkinson’s disease. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2006;28:738–754. doi: 10.1080/13803390590954236. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13803390590954236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson GS, Leverenz JB. Profile of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:640–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00373.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00373.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morley JF, Duda JE. Neuropsychological correlates of olfactory dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2011;310:228–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.05.030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brück A, Kurki T, Kaasinen V, Vahlberg T, Rinne OJ. Hippocampal and prefrontal atrophy in patients with early non-demented Parkinson’s disease is related to cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1467–1469. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.031237. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2003.031237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohen NI, Albin RL. The cholinergic system and Parkinson disease. Behav Brain Res. 2011;221:564–573. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.048. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bohnen NI, Gedela S, Herath P, Constantine GM, Moore RY. Selective hyposmia in Parkinson disease: association with hippocampal dopamine activity. Neurosci Lett. 2008;447:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.09.070. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2008.09.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baba T, Kikuchi A, Hirayama K, Nishio Y, Hosokai Y, Kanno S, Hasegawa T, Sugeno N, Konno M, Suzuki K, Takahashi S, Fukuda H, Aoki M, Itoyama Y, Mori E, Takeda A. Severe olfactory dysfunction is a prodromal symptom of dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease: a 3 year longitudinal study. Brain. 2012;135:161–169. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr321. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]