Abstract

Introduction

Opportunities to engage with nature have shown relevance in experiences of health and recovery of patients with cancer and are attracting interest in cancer care practice and design. Such healthcare innovations can widen the horizon of possible supportive care solutions but require deliberate and rigorous investigation to ensure responsible action is taken and wastage avoided. This protocol outlines a study designed to solicit knowledge from relevant experts drawn from a range of healthcare practitioners, management representatives, designers and researchers to explore levels of opinion consensus for determining opportunities for, and barriers to, providing helpful nature engagement in cancer care settings.

Methods and analysis

A 4-round modified electronic Delphi methodology will be used to conduct a structured, iterative feedback process for querying and synthesising expert opinion. Round 1 administers an open-ended questionnaire to a panel of selected, relevant experts who will consider the own recommendations of patients with cancer for nature engagement (drawn from a preceding investigation) before contributing salient issues (items) with relevance to the topic. Round 2 circulates anonymised summaries of responses back to the experts who verify and, if they wish, reconsider their own responses. Rounds 3 and 4 determine and rank experts' top 10 items using a 10-point Likert-type scale. Descriptive statistics (median and mean scores) will be calculated to indicate the items' relative importance. Levels of consensus will be explored with consensus defined as 75% agreement.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Institution's Human Research Ethics Committee (blinded for review). It is anticipated that the results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented in a variety of forums.

Keywords: ONCOLOGY, Environment, Delphi, Supportive cancer care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The aim of the study outlined in this protocol is to determine opportunities for contact with nature in oncology contexts in order to develop novel healthcare design solutions.

Own nature experiences of patients with cancer and recommendations for opportunities to engage with nature in oncology contexts form the basis for this investigation.

This study represents the first international cross-disciplinary collaboration between healthcare and healthcare facility design experts to better understand the feasibility of appropriate and helpful nature engagement in oncology contexts.

The electronic Delphi method enables experts across disciplines and geographical locations to anonymously contribute valuable knowledge and experience through a structured and iterative feedback process.

Participant sample is determined by the willingness of healthcare and design experts to participate in questionnaire surveys, which can prove challenging due to common time constraints.

Introduction

Background

With the worldwide surge in incidence, cancer will soon impact at least one in three people.1 Reducing the burden of cancer and supporting those affected by cancer has become a healthcare priority. It is known that a significant amount of this healthcare burden is preventable; one-third of lives lost to cancer are attributable to behavioural and lifestyle choices and 30% of these cancer deaths are preventable by attending to key risk factors.1 In response, healthcare policy must consider effective clinical care and alleviate the burden associated with cancer treatment and promote positive health behaviour and prevent poor lifestyle choices. Such health-centric strategies focus on patients' own resources to manage health and disease2 and aim to strengthen patients' capacity to maintain or regain good health in the context of pathogenic biological or psychosocial stressors. To this end, exposure to, and engagement with, nature presents an often underappreciated health resource3 and could be considered an opportunity to broaden health-centric care strategies: “contact with nature may offer an affordable, accessible and equitable choice on tackling the imminent epidemic, with both preventive and restorative [public] health strategies”.4 In this context, Nightingale's seminal and timeless instructions for ‘those who have personal charge of the health of others’ are still relevant for healthcare givers and receivers today: “What nursing has to do …is to put the patient in the best condition for nature to act upon him”5 (p. 133). Preliminary empirical evidence from cancer populations show various biopsychosocial benefits from contact with nature in cancer settings, including improved quality of life,6 increased positive health behaviour such as physical exercise and fruit and vegetable consumption,7 restored attention8 and increased social interaction.9

Rationale

Healthcare setting design represents an expensive intersection of healthcare industry and infrastructure as well as potential opportunities for healthcare improvements10 and increased consumer satisfaction.11 Opportunities to connect with nature are attracting interest in healthcare setting and service design. Such healthcare innovations can widen the horizon of possible solutions to growing healthcare burden but require deliberate and rigorous investigation to ensure responsible action is taken and wastage avoided. This complex issue involves multiple governing bodies and stakeholders who have the task of innovating cost-efficient and high-quality healthcare that responds to health and recovery requirements of patients with cancer.

The present study follows from phase 1 qualitative research into use of nature by patients with cancer and its relevance in their experiences of health and recovery, which uncovered their own recommendations for integrating nature engagement opportunities in healthcare. Our preliminary findings report positive health–nature interchanges for patients with cancer and support further investigation to strategically determine the opportunities for, and barriers to, safe delivery of beneficial nature engagement in cancer care contexts. To evaluate the feasibility of integrating nature engagement opportunities into healthcare, a synthesis of opinion from a range of experts is needed. This protocol outlines a study designed to solicit input from relevant experts drawn from a range of professional and academic roles (including cancer-specific experts, where relevant) and explore factors they deem critically important for the provision of nature-based engagement in cancer care settings. To the best of our knowledge, no such collection and synthesis of expert opinion on this topic exists across healthcare and design disciplines.

Aim

The primary aim is to solicit knowledge from relevant healthcare and design experts in order to explore levels of opinion consensus about opportunities for, and barriers to, providing nature engagement in cancer care settings.

Methods and design

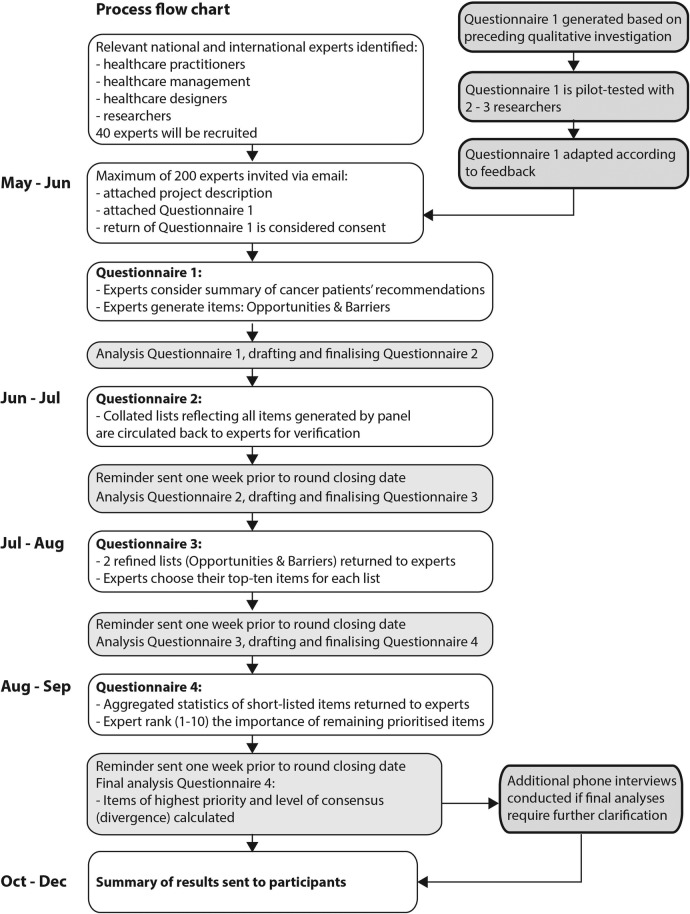

Figure 1 illustrates the study flow according to the modified Delphi methodology adopted in this study, which structures an iterative feedback process using a predetermined number of four questionnaires (rounds) rather than using as many as needed to reach strict consensus. First, an open-ended questionnaire is administered to an ‘expert panel’ with the aim to uncover salient issues (items) with relevance to the topic, which are subsequently verified and finally ranked according to their priority reflecting the relative degree of consensus among the panel. The protocol and related study materials were designed following the SPIRIT 2013 Checklist12 where appropriate.

Figure 1.

Design of modified four-round Delphi.

Rounds and timeline

Following Okoli and Pawlowski's13 recommendation, the four-round Delphi will aim to collect rich data, consolidate ranging expert opinion and indicate levels of consensus. Round 1 serves idea generation, round 2 verifies summaries of responses, round 3 short-list items of priority and round 4 ranks prioritised items. The four questionnaires will be electronically administered via email. All rounds are planned to take 4 weeks:14 2–3 weeks for panellists to respond (including reminder emails prior to the round closing deadline to maintain a high response rate), and 1 week to analyse response data and, based thereon, draft the next questionnaire.

Questionnaires

Delphi is a form of iterative enquiry that builds on ongoing data collection. Its primary research tool is a series of questionnaires built from participants' stepwise input. Questionnaire 1 will be available for distribution at the start of recruitment and questionnaires 2–4 are subsequently created to reflect content from the ongoing data collection. Questionnaire 1, section A first introduces the recommendations of patients with cancer drawn from our preceding investigation. Section B will query experts' ideas and perceptions about opportunities for nature engagement in the cancer care setting and ask for factors they perceive as barriers to its provision. Questionnaire 1 (item generation) will take not more than 15 min to complete and questionnaires 2–4 (verification and ranking) will take not more than 10 min to complete unless the panellists wish to elaborate. Questionnaire 1 will be pilot-tested by two to three researchers unfamiliar with the Delphi method who will be asked to provide feedback about their question-and-answer process when completing the questionnaire.15 This is to ensure questionnaire 1 is comprehensible to Delphi responders and that the intended scope and quality of response will be achieved.

Anonymity

The level of anonymity and confidentiality appropriate for this study is termed ‘quasi-anonymity’,16 which denotes that responses will remain anonymised throughout the study and are known only to the researchers. Since the panel constitutes experts from professional and academic backgrounds only, there is no need to adopt the common strictures of anonymity required when involving patients with cancer. Panel members will be blinded to each other's responses throughout the Delphi process but can be known to each other as panel members. It will be clearly stated that publications will not reference any personally identifiable participant information.

Participants

Selection of experts

National and international experts in academic and professional roles will be selected based on relevant backgrounds who possess both knowledge and experience representative of the capacity to articulate informed opinion and provide relevant input about the given topic. Nature engagement in cancer care is a novel topic and thus requires tapping into related expert groups, which diversely address healthcare architecture and design and supportive cancer care. Relevant professional backgrounds include, for example, oncology and allied healthcare practitioners, management representatives working in healthcare planning and development, and healthcare setting architects and designers. Academics and educators may be included if they have taught participants on health–nature and related healthcare design topics or have published and presented related research articles in academic forums.

The identification process uses two strategies. First, the researchers' own expert networks will be used and consulted for referrals to potential study participants (snowballing). Second, we will follow Delbecq et al's17 guidelines for identifying experts for nominal group studies, which will increase rigour in recruiting relevant individuals outside the researchers' own networks. This procedure has shown to be transferable to Delphi studies13 14 and includes identifying relevant disciplines, sectors, and organisations and retrieving relevant academic and practitioner literature in order to build an expert list. The following predefined inclusion criteria have been previously adopted in Delphi panel recruitment14 and will supplement the above selection procedures: (1) capable of contributing relevant input (knowledge and experience); (2) willingness and sufficient time to complete all four rounds; and (3) sufficient English skills to communicate ideas effectively. Please see the Discussion section for the definition of ‘expert’ used in this study.

Sample size

The recruitment target is a minimum of 40 experts accounting for 10 experts per group (healthcare practitioners, management representatives, designers, researchers). This will allow for diversity of views and reveal any divergence of opinion between groups, while maintaining a volume of responses that is manageable to process. The sample target takes into account that not all participants are expected to complete all four rounds (attrition) and that a minimum of seven panellists (for each group) are required for reliable outcomes and comparisons.18 To achieve the minimum sample size, a maximum of 200 experts will be invited to participate.

Recruitment

Identified experts will receive an email containing an invitation to participate, a participation information sheet and questionnaire 1. Passive consent is given by responding to the email and returning questionnaire 1. Participation is voluntary and can be withdrawn at any stage. Participants can request their demographic information and where possible other contributions to be withdrawn; however, due to the study's iterative process not all contributions can be withdrawn once included in previous rounds. Reasons for declining will be recorded if provided.

Data collection and analysis

Procedure

Questionnaires will be electronically administered via email according to Schmidt's19 sequence detailed in figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Delphi questionnaire administration process (adapted from Schmidt et al32).

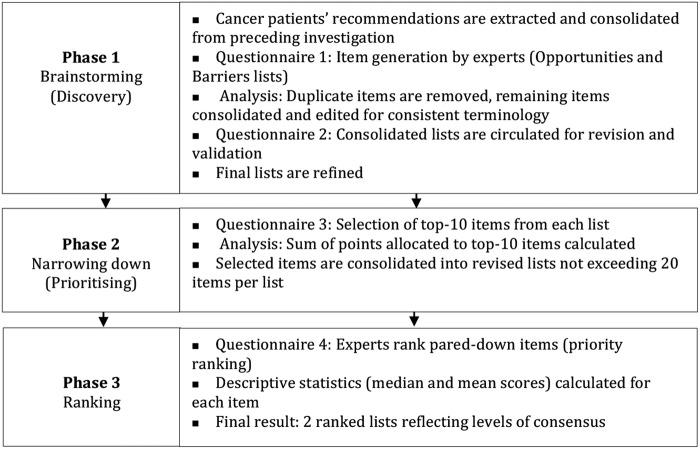

Phase 1

The initial phase constitutes creative brainstorming and aims to elicit a maximum variety of items, before quantitatively ranking them.

Questionnaire 1: generation of items

This questionnaire will be sent on the same day the expert accepts participation. Section A constitutes a summary of anonymised recommendations of patients with cancer and cautions related to nature engagement extracted from the preceding qualitative investigation. Section B asks two basic, open-ended questions requesting experts to list at least six items (as recommended by Schmidt19) for questions 1 and 2 followed by brief explanations of their chosen items. These follow:

1. List at least six items relevant to your expertise describing design features, applications, initiatives or care practices related to nature engagement, which healthcare and design practitioners could feasibly implement within the cancer care context.

This list seeks to generate a list of design and healthcare opportunities (opportunities list).

2. List at least six important barriers or risk factors that you believe affect the provision of nature opportunities in cancer care contexts. These can include, for example, physical, psychosocial, economic or political factors.

This question seeks to generate a list of barriers and key risk factors related to the provision of nature opportunities (barriers list).

Additionally, experts will be asked to offer a brief explanation of the importance of their suggested item. Space will be provided below each item for free-text description.

Analysis (questionnaire 1)

All data (items and explanations) will be entered and managed in qualitative data analysis software Nvivo V.10 for MacIntosh (QSR I. NVivo qualitative data analysis software for Macintosh, version 10: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2014 2014). The analysis will first remove identical responses, then collate, synthesise and edit remaining ideas to achieve consistent terminology of items expressing similar ideas and, finally, logically group items into emerging categories. An inter-rater process will assist interpretative congruity as recommended for thematic analysis.20

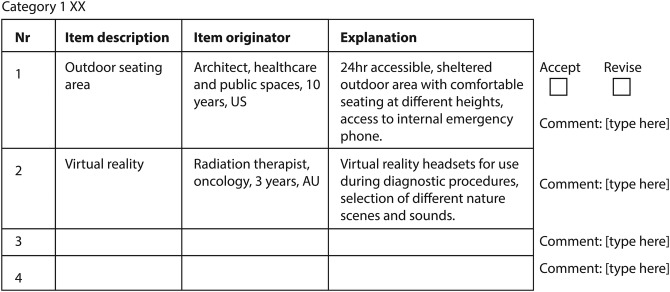

Questionnaire 2: validation of categorised items

This questionnaire will be designed based on responses from round 1 and aims to strengthen construct validity13 according to the concept of ‘member checking’.20 All items generated thus far will be collated into meaningful categories, as produced by inter-rater agreement, and will be recirculated to all experts. Each item is presented with a one-sentence explanation and non-identifiable background information of the panel member who generated the item (figure 3). A brief summary of the comments from round 1 is provided. Experts will be asked to:

Verify correct and fair interpretation of their responses and that items have been placed in an appropriate category;

Verify and, if they wish, refine the categorisations and recommend additional items.

Figure 3.

Example of questionnaire 2 layout.

Analysis (questionnaire 2)

Based on responses, items will be further refined and again subjected to inter-rater discussion.

Phase 2

In this phase, panellists will state their priorities and lists will be condensed accordingly.

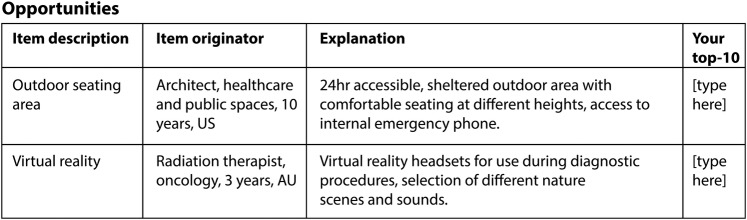

Questionnaire 3: prioritising items

Questionnaire 3 uses a structured format and will list the items generated thus far in random arrangement to minimise response bias. Each panellist will be asked to select 10 items (top 10) from each list (opportunities and barriers), which s/he deems relevant and critical to the consideration of nature opportunities in the cancer care setting. Items 1–10 are selected according to their importance as judged by the expert who is asked to assign ‘1’ to the most important item, ‘2’ to the second ranked item and so on (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Example of questionnaire 3 layout.

Analysis (questionnaire 3)

Items selected by the majority of experts will be aggregated representing a majority vote. Lists will be reduced according to the importance of items calculated based on the sum of points allocated by each expert to their top 10 items, that is, item ‘1’ indicating highest importance is coded with 10 points, item ‘2’ coded with 9 points and so on. As recommended by Schmidt,19 to avoid burdening panellists with too many items, the target size of total items for the final round will be no more than 20 items for each list (opportunities and barriers).

Phase 3

The aim of this phase is to elicit levels of agreement among all experts and detect any diverging opinion between different expert groups.

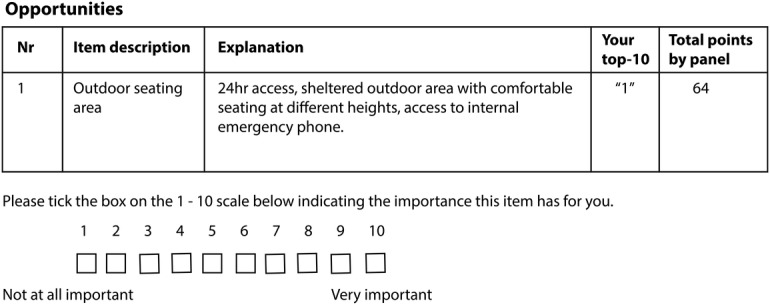

Questionnaire 4: ranking items

Questionnaire 4 is designed to elicit levels of consensus (not achieve consensus) in the ranking of relevant items. This questionnaire includes aggregated statistical group responses generated for each included item thus far: the total sum of points assigned to each item by the entire panel; individual panellists' own round 3 response and a summary of comments provided thus far (figure 5). Each panellist will individually submit a rank ordering of the items for each of the condensed list (opportunities and barriers). Each item is presented with a corresponding 10-point Likert-type scale (1=not important at all, 10=very important) and an option to indicate ‘no judgement’ for any given item including space for justification.

Figure 5.

Example of questionnaire 4 layout.

Analysis (questionnaire 4)

Statistical analyses will be performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.23 for Macintosh (IBM C. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, version 23. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2013). Descriptive statistics (median and mean scores) will be calculated to indicate items' relative importance. Descriptives will be calculated for the full sample and by expert group. The study's aim is to explore levels of consensus rather than achieve consensus. Consensus will be defined as 75% agreement.21

Finally, if further understanding of qualitative responses is required, a small number of one-on-one follow-up interviews will be conducted with experts to clarify any ambiguity and gain a fuller understanding of final results. Experts will be informed in the participation information sheet that they may be invited to participate in a voluntary follow-up interview at study completion.

Ethics

Ethics for this study was gained from the Institution's Human Research Ethics Committee (blinded for review). All consented participants will be assigned a unique identification code. Collected demographic information and contact details will include name, contact phone number, email address, description of professional role, years served in field of expertise, country of professional residence/affiliation. Participants' identifiable information will be matched with their unique identification code in a digital master file only. All data collected will be stored safely and securely in locked filing cabinets and in password-protected folders on a secure drive (electronic data) that can be accessed only by the study investigators. Data will be kept for 5 years as per local guidelines.

Discussion

Appropriateness of method

The Delphi method is an established research tool for complex problem solving, which solicits expert opinion through a structured, iterative process.19 Its original purpose was to obtain converging consensus about relative priorities in a given topic through a progression of iterative questionnaires based on controlled feedback22 until statistical census is reached. Since its inception, the Delphi method evolved to address a variety of research problems such as eliciting degrees of agreement, delineating differing group attitudes and positions, or understanding the rationales of particular judgements and opinions.18 23 Delphi variants applied to such explorative enquiry include, for example, modified, exploratory, ranking and policy Delphis, which are particularly well suited for investigating areas where little prior knowledge exists;24 where empirical data are lacking;25 and where cursory understanding of group attitudes and priorities is desired.18 The present study aims to guide concept development and elicit levels of consensus among diverse disciplinary viewpoints in order to generate new care opportunities related to nature engagement in the cancer care setting. The best-suited variant for this purpose is the modified electronic Delphi with a predefined four-round design, which provides the following key advantages: (1) serves the dual purpose of soliciting broad expert opinion followed by priority ranking;13 (2) can conclude at a predefined number of rounds because strong consensus is not required when degrees of agreement and group attitudes are of interest;18 (3) structures a rigorous and rapid feedback-based (online) communication process;26 (4) frees communication from logistical challenges, peer pressure and ‘group-think’ scenarios;27 and (5) cross-pollinates multidisciplinary expertise achieving broader understanding than would be reached from a single discipline alone.13 The method's flexibility and ability to easily assemble and coordinate participants across disciplines and geographical locations partly explain its growing popularity in medical and nursing research.16 Mullen18 reports its use in medical, health service and nursing research for “forecasting developments in medicine and health technologies”, and “identifying priorities for nursing research and also priorities for spending and service developments” (p. 49). Relevant to this study are two examples showing its application in the cancer context for gathering international input for developing pain assessment tools for palliative care,28 and engaging healthcare experts from diverse backgrounds with experience in survivorship care to develop realistic strategies for improving healthcare for cancer survivors.29

Definition of an ‘expert’

An important component of the Delphi method is the identification of experts. There are no specific standards for identifying experts and ‘expertness’ is variously defined in different Delphi studies. This presents a major criticism of the Delphi method22 30 and there remains little consensus as to what constitutes expertness and how it is operationally defined.18 22 The dictionary definition of an expert, “a person who is very knowledgeable about or skillful in a particular area,”31 has been found insufficiently instructive for assembling a Delphi expert panel.22 Consequently, studies have employed broader terms to identify and include relevant experts including ‘informed advocates’,18 ‘informed individuals’, ‘specialist in their field’ or persons with ‘knowledge about a specific subject’.16 Central to these formulations is the description of individuals who possess both knowledge and experience representative of the capacity to articulate informed opinion and provide relevant input about a given topic, which will be this study's working definition of an expert.

Composing the expert panel

Delphi studies can use homogeneous or heterogeneous expert panels depending on the study aim. A heterogeneous panel of experts can bring a range of disciplinary viewpoints to the surface and articulate greater complexities as well as the boundaries of the topic at hand. In regard to innovation, Mullen cites that “many innovations and real breakthroughs…occur from outside a discipline or specialty” (cited in ref. 18, p. 42) suggesting that cross-pollination of diverse disciplines and backgrounds can produce insightful and fruitful enquiry. Based on these precepts, five groups of diverse yet relevant stakeholders have been identified in the area of cancer care innovation: (1) patients with cancer; (2) healthcare practitioners; (3) healthcare management; (4) healthcare setting designers and (5) researchers. The panel will be composed of healthcare practitioners, management representatives, designers and researchers.

Patients' recommendations were drawn from the preceding qualitative phase 1 study and are presented to the panel in round 1. The rationale for not recruiting additional patients with cancer is twofold. First, the present study builds on a substantial amount of data already collected from qualitative interviews eliciting patient experiences, suggestions, recommendations and cautions related to nature engagement. Second, of interest, are the responses and perceptions of those who bear on decision-making and healthcare policy development to ascertain the feasibility and realistic limitations of providing opportunities for nature engagement in the cancer care setting. The strategy of using the own nature experiences and recommendations of patients with cancer for opportunities to engage with nature in oncology contexts, to form the basis for this investigation, provides experts with the opportunity of considering the perspectives of patients with cancer when developing their own views about opportunities for, and barriers to, providing helpful nature engagement in cancer care settings. It is possible that their agreement or disagreement with patients' perspectives may affect the study's findings and recommendations.

Determining sample size

Delphi studies have been conducted with varying panel sizes ranging from single digits to low hundreds.18 The absence of strict guidelines allows individual research projects to determine panel sizes according to their purpose and limitations.16 However, the most reliable Delphi studies were conducted with fewer than 20 participants.18 Recommendations suggest populating panels with 10–18 experts for sufficient input to warrant meaningful elicitation of diverse disciplinary viewpoints.13 18 Seven is considered an acceptable minimum panel size with accuracy rapidly declining as the number becomes smaller.18 It is understood that the levels of census among experts are of more interest than the power of frequencies of response,19 32 which is often misunderstood when mistaking the Delphi method for a quantitative survey.18

Level of anonymity

One of Delphi's defining features and strengths is the anonymity of responses. Mullen18 states that preserving anonymity in Delphi “removes effects of status, powerful personalities and group pressure” (p. 46–47). Keeney et al16 note that anonymity “facilitates respondents to be open and truthful about their views” (p. 197). Varying degrees of anonymity have been used in Delphi studies. Some studies have adhered to strict criteria such as anonymising responses to researchers themselves and blinding panellists to one another's identity.18 There is no agreed level of anonymity or de-identification other than preserving “the anonymity of responses…for at least part of the study”18 (p. 47). Advantages of panellists knowing each other's identities include greater motivation to engage because of association with prominent experts, stimulating exploratory thinking and idea generation, and introducing greater accountability for considered personal responses and the overall Delphi study's outcome.18 The present study will make use of these advantages and also acknowledge the known fact that complete blinding can be unrealistic because experts might know each other outside the study.16

Summary of strengths and limitations

In summary, the key strengths of the Delphi method are its flexibility to modify the study procedures (eg, number of rounds) to suit the study context; the ability to bring together experts from diverse backgrounds and locations; and participant anonymity to stimulate a free flow of ideas. The limitations include reliance on expert participants who may have limited time to contribute; the lack of a common and robust definition of ‘expertness’ in the Delphi literature; and the identification and recruitment of sufficient suitable experts when considering a low response rate in Delphi studies.

Dissemination plan

Participants will be sent a summary of results at conclusion of the final phase. Presentation of results will include the total number of items generated in phase 1 and the strength of the items taken into phase 2. Levels of consensus will be tabled and sufficient raw data provided (eg, number of panellists in each round) to support calculation of statistics. A summary of non-identifiable demographics will be presented to validate the participation of relevant and qualified experts. Based on the findings, it will be possible to revise the theoretical understandings and practical patient recommendations formulated in phase 1. Preliminary expert recommendations can be drafted for testing in the cancer care context, and propositions can be generated to inform future research. It is anticipated that the results of this research project will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented in a variety of forums, and form part of the principal investigator's dissertation.

Footnotes

Contributors: SB is the principal investigator who conceived the study and drafted the initial protocol manuscript. SB, CCOC and PS are responsible for the design of the study and CCOC and PS critically revised the manuscript and related study materials. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: SB received a doctoral scholarship during the study period (Australian Postgraduate Award).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Peter MacCallum Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Stewart B, Wild C. World Cancer Report 2014. International Agency for Research on Cancer World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonovsky A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot Int 1996;11:11–18. 10.1093/heapro/11.1.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herzog TR, Chen HC, Primeau JS. Perception of the restorative potential of natural and other settings. J Environ Psychol 2002;22:295–306. 10.1006/jevp.2002.0235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maller C, Townsend M, Pryor A et al. Healthy nature healthy people: ‘contact with nature’ as an upstream health promotion intervention for populations. Health Promot Int 2006;21:45–54. 10.1093/heapro/dai032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nightingale F. Notes on nursing: what it is, and what it is not. New York: Dover Publications Inc, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowlands J, Noble S. How does the environment impact on the quality of life of advanced cancer patients? A qualitative study with implications for ward design. J Palliat Med 2008;22: 768–74. 10.1177/0269216308093839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blair CK, Madan-Swain A, Locher JL et al. Harvest for health gardening intervention feasibility study in cancer survivors. Acta Oncol 2013;52:1110–18. 10.3109/0284186X.2013.770165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cimprich B, Ronis DL. An environmental intervention to restore attention in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 2003;26:284–92. 10.1097/00002820-200308000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherman SA, Varni JW, Ulrich RS et al. Post-occupancy evaluation of healing gardens in a pediatric cancer center. Landsc Urban Plan 2005;73:167–83. 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2004.11.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulrich RS, Zimring C, Zhu XM et al. A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. Herd Health Environ Res Des J 2008;1:61–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitehouse S, Varni JW, Seid M et al. Evaluating a children's hospital garden environment: utilization and consumer satisfaction. J Environ Psychol 2001;21:301–14. 10.1006/jevp.2001.0224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inf Manage 2004;42:15–29. 10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tetzlaff JM, Moher D, Chan AW. Developing a guideline for clinical trial protocol content: Delphi consensus survey. Trials 2012;13:176 10.1186/1745-6215-13-176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res 2003;12:229–38. 10.1023/A:1023254226592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna HP. A critical review of the Delphi technique as a research methodology for nursing. Int J Nurs Stud 2001;38:195–200. 10.1016/S0020-7489(00)00044-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delbecq AL, Van de Ven AH, Gustafson DH. Group techniques for program planning: a guide to nominal group and Delphi processes. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mullen PM. Delphi: myths and reality. J Health Organ Manag 2003;17:37–52. 10.1108/14777260310469319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt RC. Managing Delphi surveys using nonparametric statistical techniques. Decision Sci 1997;28:763–74. 10.1111/j.1540-5915.1997.tb01330.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss A, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage Publications, Inc, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:401–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker J, Lovell K, Harris N. How expert are the experts? An exploration of the concept of ‘expert’ within Delphi panel techniques . Nurse Res 2006;14:59–70. 10.7748/nr2006.10.14.1.59.c6010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Critcher C, Gladstone B. Utilizing the Delphi technique in policy discussion: a case study of a privatized utility in Britain. Public Adm 1998;76:431–49. 10.1111/1467-9299.00110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardy DJ, O'Brien AP, Gaskin CJ et al. Practical application of the Delphi technique in a bicultural mental health nursing study in New Zealand. J Adv Nurs 2004;46:95–109. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2003.02969.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKenna HP. The Delphi technique: a worthwhile research approach for nursing? J Adv Nurs 1994;19:1221–5. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01207.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linstone HA, Turoff M. The Delphi method: techniques and applications. MA: Addison-Wesley Reading, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasson F, Keeney S. Enhancing rigour in the Delphi technique research. Technol Forecast Soc 2011;78:1695–704. 10.1016/j.techfore.2011.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biondo PD, Nekolaichuk CL, Stiles C et al. Applying the Delphi process to palliative care tool development: lessons learned. Support Care Cancer 2008;16:935–42. 10.1007/s00520-007-0348-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mertens AC, Cotter KL, Foster BM et al. Improving health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer: recommendations from a Delphi panel of health policy experts. Health Policy 2004;69:169–78. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2003.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crisp J, Pelletier D, Duffield C et al. The Delphi method? Nurs Res 1997;46:116–18. 10.1097/00006199-199703000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearsall J, Hanks P. The New Oxford Dictionary. 2nd edn Oxford: Oxford English Press, 2003Expert. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidt R, Lyytinen K, Mark Keil PC. Identifying software project risks: an international Delphi study. J Manage Inform Syst 2001;17:5–36. [Google Scholar]