Abstract

Objective

This study aims to use the Dr Foster Global Comparators Network (GC) database to examine differences in outcomes following high-risk emergency general surgery (EGS) admissions in participating centres across 3 countries and to determine whether hospital infrastructure factors can be linked to the delivery of high-quality care.

Design

A retrospective cohort analysis of high-risk EGS admissions using GC's international administrative data set.

Setting

23 large hospitals in Australia, England and the USA.

Methods

Discharge data for a cohort of high-risk EGS patients were collated. Multilevel hierarchical logistic regression analysis was performed to examine geographical and structural differences between GC hospitals.

Results

69 490 patients, admitted to 23 centres across Australia, England and the USA from 2007 to 2012, were identified. For all patients within this cohort, outcomes defined as: 7-day and 30-day inhospital mortality, readmission and length of stay appeared to be superior in US centres. A subgroup of 19 082 patients (27%) underwent emergency abdominal surgery. No geographical differences in mortality were seen at 7 days in this subgroup. 30-day mortality (OR=1.47, p<0.01) readmission (OR=1.42, p<0.01) and length of stay (OR=1.98, p<0.01) were worse in English units. Patient factors (age, pathology, comorbidity) were significantly associated with worse outcome as were structural factors, including low intensive care unit bed ratios, high volume and interhospital transfers. Having dedicated EGS teams cleared of elective commitments with formalised handovers was associated with shorter length of stay.

Conclusions

Key factors that influence outcomes were identified. For patients who underwent surgery, outcomes were similar at 7 days but not at 30 days. This may be attributable to better infrastructure and resource allocation towards EGS in the US and Australian centres.

Keywords: Emergency Surgery, Outcomes

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Uses an international data set to provide a large cohort of patients for analysis.

Is built on an international collaborative that facilitates sharing of outcome data and ultimately benchmarking of clinical standards.

Identifies key hospital infrastructure factors that may influence the delivery of high-quality care with the use of hierarchical logistic regression modelling as well as examining global trends in the delivery of EGS.

Participation of only 23 centres means that true country-wide conclusions cannot be made.

The availability of data limited mortality analysis to 30-day inhospital deaths across three different healthcare systems. Without longer term outcome data, findings must be interpreted with caution.

Introduction

Emergency general surgery (EGS) involves the assessment, management and care of patients with acute abdominal pathology.1 The vast scope of this specialty covers the entire spectrum of our population and its associated burden means that EGS now accounts for ∼50% of a general surgeon's workload.2 The delivery of high-quality EGS remains a challenge for clinicians and healthcare providers across the world with outcomes following EGS admissions being significantly worse when compared with elective practice.3 Mortality rates of ∼15% following emergency laparotomy have been reported in developed nations with this figure rising to 25% in the elderly and comorbid.3 4

Although much is being performed to improve EGS services, there remains significant variation in the delivery of care.3 5 The provision of emergency service delivery and how hospitals are structured to deal with the unpredictable and acute burden of EGS admissions may account for differences in outcomes. The influence of structural factors such as consultant workload, intensive care unit (ICU) capacity and hospital volume on outcomes in EGS remains relatively unknown.

The unpredictability and variety of workload seen in EGS makes prospective data collection very challenging. Using administrative outcome data can add valuable information on patient demographics and treatment for large cohorts of patients.6 The use of an international data set allows for further analysis and comparison between different healthcare systems and may provide valuable information and insight for policymakers and clinicians to develop pathways of care and improve patient care.7

The sharing of international data in EGS is a novel concept; the Dr Foster Global Comparators (GC) Project aims to improve outcomes in healthcare by the collection and sharing of administrative data between member institutions across the world as a tool to enable quality improvement and the identification of best practice.8 The potential benefits of collecting large global data sets have already been shown by GC members in elective surgery and this study aims to examine outcomes in EGS.9

The primary aim of this study was to determine whether differences in outcome following EGS admissions exist between hospitals in the GC Project using administrative data analysis. The secondary aim was to explore the relationship between hospital structure and outcome in the delivery of care for patients admitted as general surgical emergencies (including those undergoing emergency surgery) in GC hospitals.

Method

Background to GC

GC is a clinician-led, not-for-profit subsidiary of Telstra Health. The project was conceived in 2011 and currently consists of 41 centres across 4 continents. Member institutions aim to benchmark standards using their routinely collected administrative outcome data to inform quality improvement and ultimately patient care. The GC database is managed by a team of healthcare analysts who work closely with members and are based in London. GC receives quarterly data updates from participating centres.

Participants

Data were obtained from 23 academic medical centres across 3 countries (Australia, England and the USA). Each participating unit is a member of GC. Data for English hospitals were obtained by GC from the Hospital Episodes Statistics (HES) database.10 For the other countries, electronic inpatient records were obtained directly from each participating hospital's administrative database. These hospitals were selected from within GC as the authors had access to complete data sets of patient and hospital-level data covering the period of analysis.

Inclusion

This study focused on high-risk emergency gastrointestinal surgical diagnoses. High-risk diagnoses were defined as those with a crude mortality rate of >5% as previously described by Symons et al.11 The included diagnosis codes have been broadly mapped into seven clinical conditions (bowel ischaemia, diverticulitis, liver and biliary, gastrointestinal ulcers, hernias, miscellaneous and peritonitis). Codes can be seen in online supplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2016-014484supp1.pdf (68.4KB, pdf)

All adult patients discharged from the included hospitals between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2012 who were admitted with a primary diagnosis meeting the inclusion criterion were studied whether they underwent surgery or not.

Exclusion

Centres were excluded if the authors did not have access to complete data for the period of analysis. Patients admitted with a non-gastrointestinal primary diagnosis and paediatric patients were excluded. Patients who were classed as short stay (inpatient admission for <24 hours then discharged) were also excluded.

Study procedure

Survey

A survey covering key structural aspects of an EGS admission was created and distributed to medical directors within the hospitals included in the study. The survey was developed from that used in the NELA organisational audit with modifications made to account for the international participants in the GC cohort3 (see online supplementary file 2). There was a 100% return rate of surveys from the 23 centres included in the study. The relevant results of the survey were then translated to appropriate binary codes (as they were yes/no responses) and included in statistical analysis to determine the effect of hospital structure on outcome.

bmjopen-2016-014484supp2.pdf (54.8KB, pdf)

Administrative data collection

Using the relevant ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for primary diagnoses and operative procedures from the participating countries, data were collated and analysed using the statistical software package R with the creation of logistic regression models. Surgical procedures were defined as emergency open or laparoscopic abdominal operations or emergent hernia repairs.

Outcome measures

Mortality was defined as any inhospital death within 7 or 30 days of hospitalisation. Data were not available for deaths in the community or for other healthcare facilities to which the patients may have been discharged.

Readmission was defined as any unplanned admissions to an inpatient unit at the same hospital within 30 days of discharge.

Long length of stay was defined as a length of stay greater than that of the 75th centile patient in the participant groups for the primary diagnosis as described.

Statistical analysis

Patient-level data used for risk adjustment were: diagnosis group, age, sex, country, year of discharge, comorbidity and admission source/transfers. Demographic data were analysed using simple statistical methods, the χ2 test was used for nominal data and the Kruksal-Wallis test was used to compare ages of cohorts in the three countries.

Age was divided into four groups (<60, 60–69, 70–79, >80).

The comorbidity index score was constructed from the 31 Elixhauser comorbidities, plus dementia, that were recorded against each patient on admission to hospital.12

Transfers were defined as patients being transferred from another acute hospital setting in order to receive emergency care.

A handover was defined as the transfer of care of a patient from one consultant to another within the same unit with a formalised process or protocol for this transfer being in place.

Geographical differences

A multivariate logistic regression model was created using the patient-level predictors to assess 7-day and 30-day in hospital mortality, 30-day emergency readmission to hospital and long length of stay. This allowed the authors to determine whether geographical differences in outcome exist.

Effect of hospital infrastructure

A hierarchical logistical regression model was created using the available variables to analyse hospital infrastructure factors on the four aforementioned outcome measures. A model was created for all admissions with a further model for patients who underwent surgery to see if there was a difference in these groups. The infrastructure factors that were assessed were the effect of: intensive care beds available to EGS patients, volume of EGS admissions, consultant workload factors (including whether consultants were on-site 24 hours a day while on-call) and handover of patient care between consultant shifts.

Ethics

All participating centres provide consent for the use of their administrative data for research purposes as part of GC membership. No identifiable patient data were used as part of this study, and therefore, individual patient consent was not required.

Results

Demographics

A total of 69 490 patients were included in this study, 14 881 from Australia, 29 152 from England and 25 457 from the USA. Five centres were in Australia, 10 were in England and 8 were in the USA.

Patient demographics, including age, sex and comorbidity, were similar between countries (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of all patients within study

| Australia | England | USA | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admissions (%) | 14 881 (21) | 29 152 (42) | 25 457 (37) | 69 490 | |

| Operated (%) | 3422 (18) | 8293 (43) | 7367 (39) | 19 082 | p<0.01* |

| Average age | 63 | 63 | 57 | 61 | p<0.01† |

| Female (%) | 50 | 54 | 57 | 54 | p<0.01* |

*χ2..

†Kruksal-Wallis.

Overall, a total of 27% of patients admitted underwent a surgical procedure related to their primary admission code (laparotomy or laparoscopic procedure); therefore, 73% of patients admitted to an EGS service did not undergo surgery.

Geographical trends in outcome

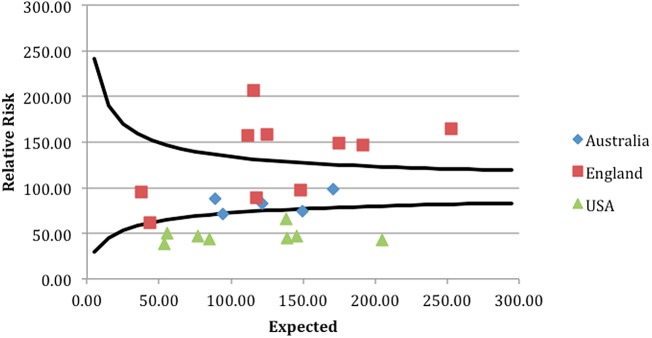

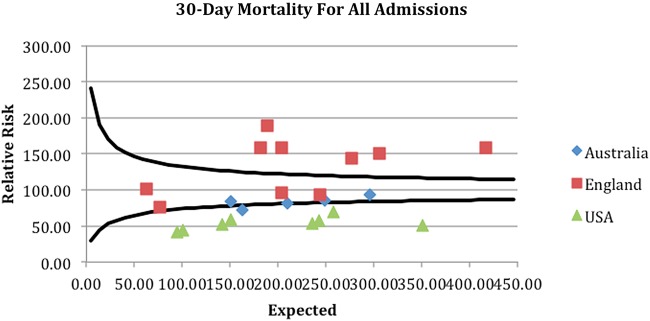

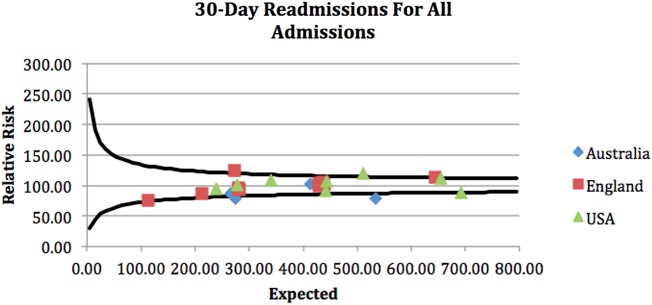

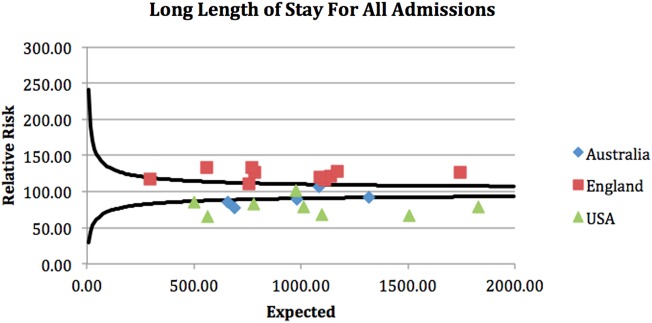

A clear geographical difference in outcome was demonstrated with associated clustering of units from each country. The funnel plots attached demonstrate that geographical differences in outcome for all patients admitted as EGS emergencies were seen across the cohort (see funnel plots—figures 1–4).

Figure 1.

Seven-day unit level mortality for all admissions.

Figure 2.

Thirty-day unit level mortality for all admissions.

Figure 3.

Thirty-day unit level readmissions for all admissions.

Figure 4.

Long length of stay at unit level for all admissions.

Overall 30-day mortality for this cohort was 8% with a mortality rate of 6% seen in the operative subgroup. Mortality analysis was subdivided to look at 7-day and 30-day outcomes, and separated into two cohorts, all-comer and those who underwent surgery, this allowed for an assessment of the impact of surgical intervention on outcome. All-comer mortality at 7 days within this cohort demonstrated ORs of 0.95 in Australia, 1.70 in England and 0.62 in the USA (reference 1.00). At 30 days, a similar picture was seen with Australia 0.90, England 1.91 and the USA 0.58 (reference 1.00). Within the postoperative subgroup, 7-day mortality ORs were the same across the cohort with OR 1.00. However, after 30 days, these results had changed to 0.74 in Australia, 1.47 in England and 0.92 in the USA.

The 30-day readmission rates showed ORs of 0.92 in Australia, 1.42 in England and 0.76 in the USA (reference 1.00). In the postoperative subgroup, readmissions were 1.32 in Australia, 1.42 in England and 0.79 in USA (reference 1.00).

Long length of stay ORs were: 0.88 in Australia, 1.98 in England and 0.58 in the USA (reference 1.00). In the postoperative subgroup, these were 0.82 in Australia, 1.56 in England and 0.78 in the USA.

All findings described above reached statistical significance with p<0.01.

Patient factors

Mortality and other outcomes improved with time; 2012 mortality, and other outcomes, were significantly improved when compared with 2007 (p<0.01 for 7-day and 30-day mortality, readmission and long length of stay in all-comer and postoperative groups) (tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Patient-level variables used in the primary logistic regression modelling to determine geographical differences in outcome between the included centres

| 7-day mortality OR (95% CI) | 30-day mortality OR (95% CI) | 30-day readmission OR (95% CI) | Long length of stay OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year (ref. 2012) | ||||

| 2007 | 1.23 (1.06 to 1.42)* | 1.37 (1.22 to 1.53)* | 1.07 (1.00 to 1.15) | 1.24 (1.17 to 1.32)* |

| 2008 | 1.10 (0.96 to 1.26) | 1.24 (1.11 to 1.39)* | 1.11 (1.04 to 1.18)* | 1.17 (1.10 to 1.24)* |

| 2009 | 1.13 (0.99 to 1.30) | 1.25 (1.12 to 1.39)* | 1.10 (1.03 to 1.17)* | 1.13 (1.07 to 1.20)* |

| 2010 | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.25) | 1.13 (1.01 to 1.26) | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.09) | 1.09 (1.03 to 1.15)* |

| 2011 | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.16) | 1.08 (0.97 to 1.20) | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.08) | 1.10 (1.04 to 1.16)* |

| Sex (ref female) | ||||

| Male | 0.92 (0.85 to 1.00) | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.03) | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.07) | 0.90 (0.87 to 0.93)* |

| Age (ref <60) | ||||

| 60–69 | 1.81 (1.54 to 2.13)* | 1.73 (1.54 to 1.95)* | 1.09 (1.03 to 1.15)* | 1.19 (1.14 to 1.25)* |

| 70–79 | 3.20 (2.77 to 3.69)* | 2.85 (2.56 to 3.17)* | 1.24 (1.17 to 1.30)* | 1.37 (1.30 to 1.48)* |

| 80+ | 7.01 (6.83 to 8.01)* | 6.11 (5.53 to 6.76)* | 1.80 (1.71 to 1.90)* | 1.43 (1.36 to 1.50)* |

| Comorbidity (ref <10) | ||||

| >10 | 2.52 (2.30 to 2.76)* | 3.83 (3.55 to 4.13)* | 2.09 (2.00 to 2.18)* | 2.69 (2.59 to 2.79)* |

| Pathology (ref HPB) | ||||

| Bowel ischaemia | 8.11 (6.97 to 9.49)* | 4.85 (4.32 to 5.44)* | 1.70 (1.58 to 1.84)* | 0.49 (0.45 to 0.52)* |

| Bowel obstruction | 1.13 (0.97 to 1.32) | 0.93 (0.83 to 1.03) | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.08) | 0.64 (0.61 to 0.67)* |

| Peritonitis | 5.23 (4.36 to 6.26)* | 3.11 (2.70 to 3.57)* | 1.59 (1.46 to 1.79)* | 0.63 (0.58 to 0.68)* |

| Diverticulitis | 1.90 (1.54 to 2.35)* | 1.52 (1.30 to 1.78)* | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.14) | 2.17 (2.02 to 2.34)* |

| GI ulcers | 3.03 (2.43 to 3.78)* | 2.72 (2.31 to 3.20)* | 1.14 (1.02 to 1.26) | 1.65 (1.51 to 1.81)* |

| Hernias | 1.04 (0.82 to 1.32) | 0.83 (0.70 to 0.99) | 0.75 (0.68 to 0.82)* | 1.62 (1.51 to 1.73)* |

| Miscellaneous | 5.13 (4.35 to 6.04)* | 3.32 (2.94 to 3.76) | 1.69 (1.57 to 1.83)* | 1.41 (1.31 to 1.51)* |

The data presented are for all EGS admissions (Cohort of 69 490 patients).

*p<0.01.

Table 3.

Patient-level variables used in the primary logistic regression modelling to determine geographical differences in outcome between the included centres

| 7-day mortality OR (95% CI) | 30-day mortality OR (95% CI) | 30-day readmission OR (95% CI) | Long length of stay OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year (ref 2012) | ||||

| 2007 | 1.17 (0.84 to 1.63) | 1.23 (0.97 to 1.55) | 1.10 (0.97 to 1.26) | 1.17 (1.05 to 1.30) |

| 2008 | 1.03 (0.75 to 1.42) | 1.30 (1.05 to 1.62) | 1.14 (1.00 to 1.29) | 1.18 (1.06 to 1.31)* |

| 2009 | 0.99 (0.71 to 1.36) | 1.13 (0.90 to 1.42) | 1.08 (0.95 to 1.23) | 1.13 (1.02 to 1.25)* |

| 2010 | 1.10 (0.81 to 1.50) | 1.06 (0.85 to 1.32) | 1.04 (0.92 to 1.18) | 1.01 (0.92 to 1.12) |

| 2011 | 0.96 (0.70 to 1.31) | 0.98 (0.79 to 1.23) | 1.04 (0.92 to 1.18) | 1.15 (1.04 to 1.27)* |

| Sex (ref female) | ||||

| Male | 0.86 (0.71 to 1.04) | 0.95 (0.83 to 1.08) | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.15) | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.99)* |

| Age (ref <60) | ||||

| 60–69 | 2.08 (1.52 to 2.85)* | 1.94 (1.57 to 2.41)* | 1.11 (1.00 to 1.23) | 1.38 (1.28 to 1.50)* |

| 70–79 | 2.84 (2.12 to 3.81)* | 2.66 (2.17 to 3.25)* | 1.21 (1.09 to 1.34)* | 1.68 (1.54 to 1.83)* |

| 80+ | 4.57 (3.44 to 6.05)* | 4.52 (3.72 to 5.48)* | 1.62 (1.45 to 1.80)* | 1.90 (1.74 to 2.09)* |

| Comorbidity (ref <10) | ||||

| >10 | 2.58 (2.07 to 3.21)* | 3.79 (3.23 to 4.45)* | 2.19 (2.01 to 2.38)* | 2.83 (2.65 to 3.08)* |

| Pathology (ref HPB) | ||||

| Bowel ischaemia | 7.62 (4.48 to 12.96)* | 4.59 (3.26 to 6.45)* | 1.82 (1.51 to 2.19)* | 0.47 (0.40 to 0.56)* |

| Bowel obstruction | 0.45 (0.26 to 0.78)* | 0.62 (0.44 to 0.87) | 0.73 (0.63 to 0.86)* | 0.72 (0.63 to 0.81)* |

| Peritonitis | 3.16 (1.78 to 5.63)* | 2.00 (1.37 to 2.93)* | 1.16 (0.95 to 1.42) | 0.41 (0.34 to 0.48)* |

| Diverticulitis | 1.06 (0.47 to 2.40) | 1.18 (0.70 to 1.99) | 0.99 (0.74 to 1.32) | 1.71 (1.32 to 2.20)* |

| GI ulcers | 1.19 (0.66 to 2.16) | 1.56 (1.09 to 2.24) | 0.73 (0.61 to 0.89) | 0.81 (0.69 to 0.94)* |

| Hernias | 0.65 (0.37 to 1.15) | 0.54 (0.37 to 0.78)* | 0.54 (0.46 to 0.64) | 0.70 (0.61 to 0.80)* |

| Miscellaneous | 2.27 (1.26 to 4.08)* | 1.69 (1.15 to 2.47)* | 1.14 (0.94 to 1.39) | 1.20 (1.01 to 1.42) |

The data presented are for the subgroup of patients who underwent surgery (cohort of 19 082 patients).

*p<0.01.

Increasing age and comorbidity were associated with worse outcomes (p<0.01 in all outcome analyses).

Presenting pathology was also associated with outcome, with bowel ischaemia and peritonitis associated with the highest levels of mortality in the all-comer and postoperative groups (p<0.01).

Transfer from another unit was also associated with worse outcomes (p<0.01 in all analyses).

Hospital-level factors

Intensive care

ICU availability was associated with significantly improved outcomes. For every additional ICU bed per 100 hospital beds (range 2–14), a 5% cumulative improvement in 7-day and 30-day mortality was seen in the all-comer group (p<0.01). Within the postoperative subgroup, a 6% per additional hospital bed improvement in mortality was seen at 7 and 30 days (p<0.01). Increased ICU availability did not influence readmission rates or length of stay (tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Hospital-level variables used in the hierarchical regression model to determine which structural factors affect outcomes

| 7-day mortality OR (95% CI) | 30-day mortality OR (95% CI) | 30-day readmission OR (95% CI) | Long length of stay OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer (ref no) | Transfer in | 2.06 (1.53 to 2.77)* | 1.93 (1.53 to 2.44)* | 1.16 (1.01 to 1.34) | 1.44 (1.27 to 1.64)* |

| Volume (ref <3000) | 3000–4000 | 0.84 (0.75 to 0.95)* | 0.89 (0.81 to 0.98) | 1.04 (0.98 to 1.09) | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.11) |

| >4000 | 1.08 (0.97 to 1.17) | 1.06 (0.98 to 1.16) | 0.99 (0.94 to 1.05) | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.05) | |

| Consultant on-site 24 hours (ref not) | Onsite | 1.01 (0.74 to 1.36) | 1.00 (0.80 to 1.25) | 1.28 (1.14 to 1.42)* | 0.98 (0.89 to 1.08) |

| Consultant cleared of elective commitments (ref no) | Cleared | 1.04 (0.91 to 1.20) | 0.95 (0.85 to 1.06) | 0.94 (0.88 to 1.01) | 0.78 (0.74 to 0.83)* |

| Primary assessment (ref trainee) | Assessment by Consultant | 1.01 (0.83 to 1.22) | 1.19 (1.03 to 1.38) | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.13) | 1.24 (1.15 to 1.34)* |

| Handovers (ref no) | Handovers | 0.94 (0.80 to 1.11) | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.14) | 0.98 (0.92 to 1.06) | 1.07 (1.01 to 1.14) |

| Dedicated EGS operating theatre (ref no) | Dedicated EGS Operating Theatre | 0.94 (0.83 to 1.06) | 0.91 (0.82 to 1.00) | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.06) | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.02) |

| Surgical assessment unit present (ref no) | Surgical Assessment Unit Present | 1.25 (1.12 to 1.39)* | 1.32 (1.21 to 1.43)* | 1.08 (1.03–1.14)* | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.11) |

| ICU beds | ICU beds per 100 hospital beds | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.95)* | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.96)* | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.00) | 1.01 (1.01 to 1.02)* |

The data presented for all EGS admissions in the study (cohort of 69 490 patients).

*p<0.01.

Table 5.

Hospital-level variables used in the hierarchical regression model to determine which structural factors affect outcomes

| 7-day mortality OR (95% CI) | 30-day mortality OR (95% CI) | 30-day readmission OR (95% CI) | Long length of stay OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer (ref no) | Transfer in | 1.62 (0.82 to 3.22) | 1.49 (0.94 to 2.38) | 1.08 (0.82 to 1.41) | 1.42 (1.25 to 1.61)* |

| Volume (ref <3000) | 3000–4000 | 0.87 (0.66 to 1.13) | 0.82 (0.68 to 0.99) | 0.98 (0.88 to 1.09) | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.14) |

| >4000 | 1.07 (0.85 to 1.35) | 0.87 (0.74 to 1.04) | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.07) | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.05) | |

| Consultant onsite 24 hours (ref not) | Onsite | 0.74 (0.48 to 1.12) | 0.67 (0.47 to 0.98) | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.15) | 0.91 (0.78 to 1.07) |

| Consultant cleared of elective commitments (ref no) | Cleared | 1.35 (1.09 to 1.67)* | 1.04 (0.83 to 1.31) | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.16) | 0.80 (0.72 to 0.89)* |

| Primary assessment (ref trainee) | Assessment by consultant | 0.89 (0.65 to 1.72) | 1.08 (0.80 to 1.45) | 1.11 (0.93 to 1.32) | 1.11 (0.96 to 1.27) |

| Handovers (ref no) | Handovers | 0.79 (0.57 to 1.10) | 1.01 (0.78 to 1.31) | 0.99 (0.86 to 1.15) | 1.19 (1.06 to 1.34)* |

| Dedicated EGS operating theatre (ref no) | Dedicated EGS operating theatre | 0.92 (0.70 to 1.22) | 0.95 (0.78 to 1.17) | 1.05 (0.93 to 1.19) | 0.89 (0.80 to 0.98) |

| Surgical assessment unit (ref no) | Surgical assessment unit | 1.26 (0.99 to 1.62) | 1.29 (1.09 to 1.54)* | 1.09 (1.00 to 1.20) | 1.02 (0.95 to 1.10) |

| ICU beds | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.98)* | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.02) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.02) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) |

The data presented are for the subgroup of patients who underwent surgery (cohort of 19 082 patients).

The four funnel plots (figures 1–4) were created by using patient-level variables in a multivariate logistic regression model and demonstrate differences in geographical trends and outcome between the 23 GC centres included in this study. (n=69 490 in all funnel plots.)

----=99.8% control limits.

*p<0.01.

Volume

Volume was categorised into low-volume, middle-volume and high-volume units based on EGS admissions during the study period. Low-volume centres saw <3000 EGS admissions, middle volume had 3000–4000 EGS admissions and high-volume centres saw >4000 EGS admissions. Middle-volume units were associated with the best outcomes with a 16% improvement in 7-day all-comer mortality (p<0.01) and 11% improvement in 30-day mortality (p=0.02) when compared with low-volume and high-volume centres.

In the postoperative subgroup, middle-volume units were associated with an 18% improvement in 7-day mortality compared with low-volume centres (p=0.03).

There was no significant association between hospital volume and readmission rates and long length of stay.

Consultant workload

The working pattern of consultant surgeon's on-call for EGS was examined. Having a consultant based onsite 24 hours a day while on duty was associated with a 33% improvement in 30-day mortality rates in the postoperative subgroup (p=0.04). However, there was no significant improvement in outcome for all other measures of mortality in this area. An English registrar (or Australian/US equivalent resident surgeon) making the primary surgical assessment rather than a consultant was not associated with any difference in mortality across all cohorts.

Clearing consultant surgeons of elective commitments while on duty for EGS was associated with a significant improvement in 7-day mortality in the procedure subgroup, OR 0.65 (p<0.01). Having surgeons free of elective commitments was also associated with a 22% improvement in long length of stay for EGS patients (p<0.01).

Handovers

The presence of a formal handover process and the number of handovers of EGS patients was not associated with adverse outcomes.

Discussion

This study is unique as it is the first to examine a combination of geographical trends in outcomes in EGS admissions and how they may be influenced by structural factors within hospitals. The use of administrative data to inform clinicians of outcomes has been successfully implemented across many areas of surgery; however, this is the first study to examine outcomes in high-risk EGS across a number of countries. The GC project has been at the forefront of using the power of administrative data to examine global outcomes, so that different healthcare systems can learn from each other and identify best practice from the sharing of outcome data.9

Although many steps are being taken to implement improvement in the delivery of EGS,3 5 13–15 the findings from this study illustrate areas where care could be improved such as increased provision of intensive care beds and defining appropriate surgeon working patterns. Improvements in practice have been demonstrated with mortality rates reducing over the time of the study from 2007 to 2012; however, the overall mortality remained at 6% for patients undergoing EGS procedures which is much higher than in elective practice where the predicted mortality is <2% following an elective laparotomy.1

Most of the US hospitals within this cohort had established acute care surgery (ACS) programmes that are shown to be associated with improved outcomes in EGS as well as the highest ratios of ICU beds available within their hospitals.13 In Australia, the Victorian Audit of Surgical Mortality has demonstrated a temporal increase in the use of ICU availability for emergency and high-risk surgical patients and this has been associated with improvements in mortality and these changes are reflected in the outcomes seen from the Australian centres in this study.14 15

Previously published work has showed that senior clinician involvement is associated with improved outcomes in surgery and this study supports this.13 16 However, the most notable finding from this study is the impact of ICU support in improving mortality for EGS patients. A 6% improvement in mortality was seen for every additional ICU bed per 100 hospital beds (p<0.01). This may go some way to explain the geographical differences in outcome as US hospitals had a greater proportion of ICU beds compared with those in Australia and the UK. A similar picture was seen in a recent UK study which examined EGS outcomes in UK hospitals.11 It is important for those involved in the delivery of EGS to recognise that it is a multidisciplinary specialty and appropriate support services such as: ICU, radiology and pathology are essential to providing high-quality care.

A commonly occurring theme in 21st century healthcare is the centralisation of services to specialist units. This has been seen in elective cardiac, oesophagogastric and vascular surgery with successful results.17 The USA is also in the process of centralising EGS services as part of the ACS model, which encompasses EGS, trauma and surgical critical care in large specialist units.5 It is thought that improved outcomes seen in large units are due to a high volume of workload and concentrations of expertise and resources allowing for patients to receive optimal care.13 This study shows that centralisation may not be appropriate for EGS as transfers from other units as well as high-volume centres were associated with poor outcomes and increased mortality. This may be due to the acute nature of EGS meaning that delays caused by transfers, or having to wait for treatment in busy high-volume centres, may lead to adverse outcomes, making centralisation inappropriate unlike in the aforementioned elective specialties. Further work needs to be performed to explore this as it may be that the patients in these hospitals had more complex pathology and therefore may have had a greater risk of mortality as the largest centres had the most complex workload with sick patients being transferred in from smaller units.

The limitations of presenting administrative data findings are well recognised, as results are dependent on the quality of coding which can result in cases being inappropriately included or omitted from the data set. However, the large number of patients included in our cohort counters this argument. Having outcome data for almost 70 000 patients coupled with the degree of statistical significance seen in the results shows that the trends observed are of clinical importance.

It is important to highlight that the findings from this study are only based on a limited number of centres (23) within the countries examined; therefore, they may not be representative of outcomes across countries as a whole. As the majority of centres were large academic surgical units, outcomes in other units in the selected countries may differ and the overall mortality figures, of 8% and 6% in the subgroup who underwent surgery, are lower than findings previously described from the UK and USA.18 The recent publication of data from the UK National Emergency Laparotomy Audit showed an overall mortality rate of 11% after emergency laparotomy in the UK and previous literature cites mortality rates of between 15% and 25% following emergency laparotomy.3 4 19 The lower mortality rates (6%) seen in the operative subgroup compared with the non-operative subgroup may be explained by the fact that patients within this cohort were initially deemed fit enough to undergo surgery and were always more likely to survive than those deemed unfit. The differences in mortality may therefore be a reflection of decision-making from clinicians who deliver high-risk EGS services to select patients for surgery who are more likely to survive and to treat the sicker or highly comorbid conservatively or with palliative care.

The outcomes examined were limited by the availability of data. Therefore, mortality examination was confined to inhospital mortality within 30 days. This may mean that patients dying in the community following discharge or transfer to another healthcare facility would be missed. The US hospitals in this study are major academic medical centres that receive tertiary and quaternary referrals. Established US practice at this type of institution is to transfer patients out to a lower level of care such as a skilled nursing facility much earlier than might be performed in the UK or Australia. This difference in practice may account for some of the perceived improved outcomes, as adverse events occurring elsewhere are not recorded within the institution's administrative database.

Examining mortality for a longer period of time (60–90 days) may also demonstrate a change in outcomes between units. Thirty days are a relatively short period of time to follow-up patients and patients with high-risk pathology may remain in a high-dependency environment during this time. A similar picture in 30-day mortality between English units was seen in elective colorectal resections; however, when follow-up was extended to 90 days and beyond, it was felt a more accurate interpretation of outcomes and identification of high and low-performing units was seen.20 It may be that patients in US units have prolonged ICU stays due to the greater resource availability seen. Therefore, these patients may be dying at a later stage and were not recorded in our analysis. Overall patterns in EGS outcomes, particularly mortality, may be similar if longer follow-up data were available.

This study did not explore the economic impact of delivering EGS services within GC hospitals. It is well recognised that the USA has the greatest expenditure of GDP (16.9%) on healthcare in the world with the UK and Australia spending lower proportions of their GDP (9.3% and 9.1%, respectively).21 It is not known whether the UK and Australia provide similar resource allocation to EGS delivery as the USA. Further work in collaboration with healthcare economists and policymakers is required to explore this further.

This work has generated questions that will impact significantly on the delivery of EGS. The question now remains how can these findings be successfully implemented into clinical practice to improve care for this high-risk cohort of patients.

Footnotes

Collaborators: On behalf of the members of the GI GOAL, Dr Foster Global Comparators Project.

Contributors: PC, MJ and NC contributed to the conception and design of the study, model creation, data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, review and final approval. DC, AWD, ODF and CJP contributed to the conception and design of the study, model creation, data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, review and final approval. EMB and SA contributed to the conception and design of the study, model creation, data interpretation, manuscript writing, review and final approval.

Funding: PC, SA and AWD are funded by The National Institute of Health Research Imperial Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. NC and MJ are funded by Dr Foster Intelligence (a not-for-profit charitable division of Telstra Health). EMB is supported by a Cancer Research UK Clinical Lectureship (C42671/A13720). ODF's Surgical Outcome Trials and Epidemiology Centre at St Mark's Hospital is funded partly through the St Mark's Hospital Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The GC Scientific Research Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Any further information required related to this study may be requested from the corresponding author, data are held confidentially at the Global Comparators Project, Dr Foster, London.

References

- 1.The Royal College of Surgeons of England. Emergency Surgery: Standards for Unscheduled Care. http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/publications/docs/emergency-surgery-standards-for-unscheduled-care (accessed 3 Feb 2016).

- 2.The Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. Emergency Surgery: The Future. http://www.asgbi.org.uk/en/publications/consensus_statements.cfm (accessed 3 Feb 2016).

- 3.Saunders DI, Murray D, Pichel AC et al. Variations in mortality after emergency laparotomy: the first report of the UK Emergency Laparotomy Network. Br J Anaesth 2012;109:368–75. 10.1093/bja/aes165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Temimi MH, Griffee M, Enniss TM et al. When is death inevitable after emergency laparotomy? Analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Programme. J Am Coll Surg 2012;215:503–11. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagaraja V, Eslick GD, Cox MR. The acute surgical unit model versus the traditional on-call model: a systematic review and meta analysis. World J Surg 2014;38:1381–7. 10.1007/s00268-013-2447-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel AA, Singh K, Nunley RM et al. Administrative databases in orthopaedic research: pearls and pitfalls of big data. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2016;24:172–9. 10.5435/JAAOS-D-13-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruiz M, Bottle A, Aylin PP. The Global Comparators project: international comparison of 30-day in-hospital mortality by day of the week. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:492–504. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Doctor Foster Global Comparators Network. http://www.drfoster.com/tools/global-comparators (accessed 21 Dec 2015).

- 9.Munasinghe A, Singh B, Mahmoud N et al. Reduced perioperative death following laparoscopic colorectal resection: results of an international observational study. Surg Endosc 2015;29:3628–39. 10.1007/s00464-015-4119-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.http://www.hicic.gov.uk/hes (accessed 14 Oct 2015).

- 11.Symons NR, Moorthy K, Almoudaris AM et al. Mortality in high-risk emergency general surgical admissions. Br J Surg 2013;100:1318–25. 10.1002/bjs.9208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chana P, Burns EM, Arora S et al. A systematic review of the impact of dedicated emergency surgical services on patient outcomes. Ann Surg 2016;263:20–7. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Victorian Audit for Surgical Mortality. https://www.surgeons.org/for-health-professionals/audits-and-surgical-research/anzasm/vasm/ (accessed 9 Jan 2017).

- 15.Watters DA, Babidge WJ, Kiermeier A et al. Perioperative mortality rates in Australian public hospitals: the influence of age, gender and urgency. World J Surg 2016;40:2591–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dultz LA, Pachter HL, Simon R. In-house trauma attendings: a new financial benefit for hospitals. J Trauma 2010;68:1032–7. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d86471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland. The provision of emergency vascular services. London: VSGBI, 2007. (revised 2011) (accessed 4 Mar 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ingraham AM, Cohen ME, Raval MV et al. Comparison of hospital performance in emergency v elective general surgery operations at 198 hospitals. J AM Coll Surg 2011;212(1):20–8.e1. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Second National Emergency Laparotomy Audit Organisational Report. http://www.nela.org.uk/reports.htm (accessed 7 Sep 2016).

- 20.Byrne B, Faiz OD. Population-based cohort study comparing 30 and 90 day institutional mortality rates after colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 2015;100:1810–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-expenditure.htm (accessed 7 Feb 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014484supp1.pdf (68.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-014484supp2.pdf (54.8KB, pdf)