Abstract

Background

Rural communities in the Amazonian southern border of Ecuador have benefited from governmental social programmes over the past 9 years, which have addressed, among other things, diseases associated with poverty, such as soil transmitted helminth infections. The aim of this study was to explore the prevalence of geohelminth infection and several factors associated with it in these communities.

Methods

This was a cross sectional study in two indigenous communities of the Amazonian southern border of Ecuador. The data were analysed at both the household and individual levels.

Results

At the individual level, the prevalence of geohelminth infection reached 46.9% (95% CI 39.5% to 54.2%), with no differences in terms of gender, age, temporary migration movements or previous chemoprophylaxis. In 72.9% of households, one or more members were infected. Receiving subsidies and overcrowding were associated with the presence of helminths.

Conclusions

The prevalence of geohelminth infection was high. Our study suggests that it is necessary to conduct studies focusing on communities, and not simply on captive groups, such as schoolchildren, with the object of proposing more suitable and effective strategies to control this problem.

Keywords: helminths, indigenous population, chemoprophylaxis, Ecuador

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A cross sectional study carried out in indigenous communities of extreme poverty described the prevalence of geohelminth infection.

The strategy used involved 80% of inhabitants, and only 1 in every 3 homes was free of geohelminth infection.

This study was an exercise in community participation, conceived as a mechanism for achieving greater democracy.

This study was limited by the low participation rate of men of working age.

Collection of a single stool sample may mean that prevalence was underestimated.

Introduction

Soil transmitted helminthiasis is a neglected tropical disease which particularly affects low and low–medium income population groups. The social and health consequences become evident through academic performance, nutritional status, economic development and chronic infection.1 Both Ascaris lumbricoides and whipworm (Trichuris trichiura) are transmitted through food and water contaminated by faeces of infected individuals, while Ancylostoma duodenale (hookworm) is transmitted by walking barefoot on contaminated soil, or by ingestion of larva.2

The situation is particularly serious in populations with high rates of migration and mobility within and between rural and urban communities, and hence these infections continue to spread.3

Since the announcement in 20014 of a commitment to eliminate soil transmitted helminthiasis in low transmission areas, and reduce morbidity in high transmission areas, reports from various places around the world indicate that these goals are not being met, despite the established chemoprophylactic models.5

Ecuador, a multi-ethnic, low–medium income country, initiated a process of social and economic reform in 2007 which has been reflected, for example, in a rise of 122% in public health spending and in the proportion of the gross domestic product during the period 2000–2011.6

Among the various social policies is the antipoverty conditional cash transfer programmes (‘human development subsidies’—for instance, subsidies for school books and school uniforms), aimed at assisting people in extreme poverty.7 On the other hand, Ecuador has had one of the highest rates of internal and external migration, including inhabitants of the Amazonian region.8

In the Amazonian southern border area, the object of the present study, 34% of dwellings are considered to be of poor quality (bare earth floor, gaps in house walls, roof of metal or palm leaves), 55% use water from a well, river or a rainwater collection system, and only 22% are connected to a sewage network.9 These communities, located approximately 45 km from the nearest urban area and nearest communication centre, until 5 years ago were only accessible via unpaved roads, and residents could only get to health facilities and administrative municipal offices via narrow tracks through the jungle.

In Ecuador, there are no data on the prevalence of soil transmitted helminthiasis, nor on systematic coverage of prophylactic treatment or epidemiological surveillance. However, according to official figures covering the whole country, all children aged 2–5 years should have received chemoprophylaxis in 2014.10

In an effort to increase the visibility of health problems in population areas which are so small that classic studies tend to conceal them, the GRAAL research group (Grups de Recerca d'Amèrica i Âfrica Llatines) conducts studies on infectious/contagious diseases focusing on vulnerable, and often high risk, population groups, often invisible in national level epidemiological analyses. This approach has been termed patchwork studies.11

In the present study, in two indigenous communities of the Amazonian southern border of Ecuador, we aimed to quantify the prevalence of soil transmitted helminthiasis at both the household and individual levels, as well as its relationship with several variables of interest.

Methods

In June 2015, a cross sectional study was performed in two communities, once agreement and the consent of local authorities had been obtained, based on criteria of convenience in a community assembly where local political and health personnel were represented. Although no censuses were available for these communities, they are estimated to have about 240 inhabitants, according to their leaders. Both communities can be reached by road, and are situated approximately 540 km (10 hours’ travelling time) from the capital of Ecuador, Quito.

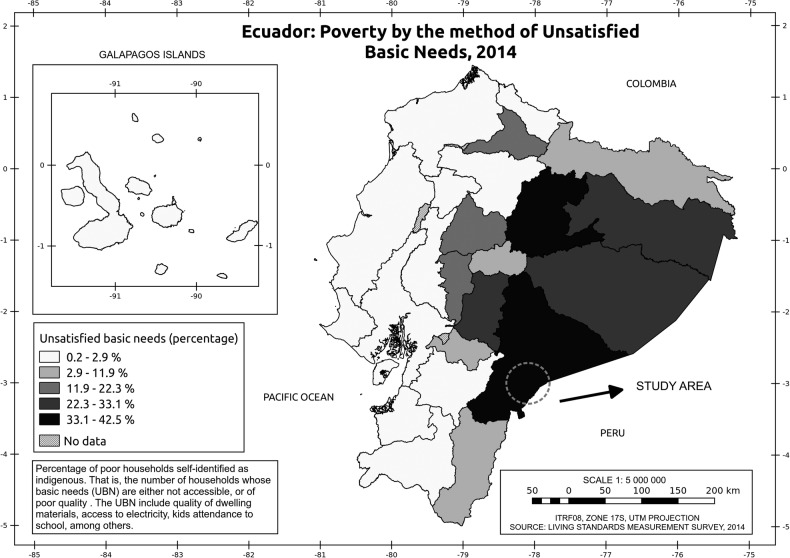

Figure 1 shows the participating communities and their geographical location, as well as the joint distribution of the proportion of households self-identified as indigenous and categorised as poor based on a measure known as the unsatisfied basic needs index. These communities are located in the Amazon border, which is one of the two Ecuadorian areas with more poverty among the indigenous population.12

Figure 1.

Distribution of the proportion of households self-identified as indigenous and categorised as poor based on the unsatisfied basic needs* index and community participants. *Unsatisfied basic needs index: percentage of poor households self-identified as indigenous—that is, the number of households whose basic needs are either not accessible or of poor quality. The index includes quality of dwelling materials, access to electricity and attendance at school, among other items.

Following the patchwork methodological scheme, which has been applied by our research team to analyse health problems such as pulmonary tuberculosis and sylvatic rabies,13 14 we administered a questionnaire (face to face) to identify dwellings and obtain household characteristics, including presence or absence of water supply and sanitary toilets, whether households boil water for consumption, overcrowding and whether they received any subsidy. At the individual level, we recorded temporary migratory movements, self-perceived presence of geohelminths in the past month and whether they had received preventive chemoprophylaxis. This could only be ascertained for the last month, due to problems in the recording of information about administration of chemoprophylaxis in the studied communities. The medication (albendazole 400 mg, single dose) was provided by the Ecuador Ministry of Public Health. For children aged <8 years, the questions were answered by the mother or guardian.

One direct faecal sample was collected from each participant. All samples (n=192) were examined using direct observation, 178 samples by the Kato–Katz technique and 184 by formol–ether concentration. In the latter two cases, missing data corresponded to samples that were insufficient to permit assessment. A positive sample was defined by the presence of at least one egg or larva detected by any one of the three methods. Direct observation and the Kato–Katz method were used to assess samples on the same day on site, in the communities, with a mobile parasitological analysis laboratory installed. The Kato–Katz technique was performed with a template of 41.7 mg, as recommended by the WHO.15 Samples were preserved in formol–ether and analysis of this concentrate was performed at a base laboratory. All three techniques have been used in other studies in Ecuador.16 17

In the cases of the Kato–Katz method and formol–ether concentrate analyses, the result recorded was the highest value obtained after examining two aliquots. Eggs per gram of faeces (epg) were calculated using the helminth eggs counted for each parasite species obtained from the Kato–Katz technique multiplied by a factor of 24, as recommended by the WHO for the template used. Egg counts as epg were utilised to classify the intensity of infection as slight, moderate or high, respectively, as follows: for A lumbricoides 1–4999 epg, 5000–49 999 epg and ≥50 000 epg; for T trichuria 1–999 epg, 1000–9999 epg and ≥10 000 epg.18

Results

The study included 59 households, and a total of 320 individual members. The number of members per household ranged from 2 to 13 (average 5.4, median 5). At least one functionally illiterate person was identified in 33.3% of the households studied; 15.4% of households had to travel by walking to get to the nearest health facility while the remainder used ground based public transport; and 72.4% of households reported that at least one member had expelled geohelminths in the last month. Fifty-nine households provided faecal samples (average number of members providing a sample 3.1; median, 3).

In 16 (27.1%) of the households which provided faecal samples, no geohelminths were observed. In another 30 (50.8%), one or more members were infected, and in 13 (22.0%; 95% CI 12.1 to 32.8) all faecal samples were positive.

All inhabitants used natural spring water, which is piped to community tanks without any type of treatment; no communities had toilets. Other sanitary and/or socioeconomic deficiencies were observed in 49.2% of households (bare earth floor, windows not covered, no wastewater disposal system, no electricity, absence of own drinking water supply), and in 79.3% (23/29) of these, at least one member was infected by geohelminths. In a similar fashion, among households with better conditions, 66.7% (20/30) presented one or more infected members (PR 1.19; 95% CI 0.86 to 1.67).

Forty-four (74.6%) households reported receiving one or more state subsidies. Of them, 81.8% had infected members compared with 46.7% (7/15) in households not receiving any subsidies (PR 1.75; 95% CI 1.09 to 3.97).

Twenty-nine (49.2%) of the households reported overcrowding (more than three inhabitants per bedroom), of which 86.2% had infected members (PR 1.44; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.99) versus 60.0% (18/30). Among the 36 households declaring they did not boil water, 28 (77.8%; 95% CI 64.2 to 91.4) had geohelminths infection whereas the corresponding values among households reporting they did boil water was 63.6% (95% CI 53.3% to 73.8%) (PR 1.22; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.88).

Of the 192 participants who provided faecal samples, 106 (55.2%) were women. Mean age was 22.8 (SD 19.4) years: 25th percentile corresponded to 8 years, 50th percentile 14 years and 75th percentile 38 years (range 76). Median ages for men and women were 10 and 18 years, respectively (p<0.05); 37% of working age men reported having to migrate for work related reasons (hunting, agriculture, mine work), tending to be away for 8–15 days, or even more.

Positivity for the presence of soil transmitted helminths was detected in 28.6% of the 192 samples analysed by direct observation, 39.9% by the Kato–Katz method and 31.5% by the formol–ether concentrate. It was possible to analyse 178 cases by both direct observation and the Kato–Katz method, of which 105 were negative for both (59%); 20 were negative according to direct observation but positive for Kato–Katz, two were positive according to direct observation but negative for Kato–Katz and 51 were positive for both (28.9%). Determinations obtained both by direct observation and analysis of the formol–ether concentrate coincided in 184 cases: 119 were negative (64.7%) and 45 (24.5%) positive for both, 13 were negative according to direct observation but positive according to the formol–ether method and 7 were positive by direct observation but negative according to the formol–ether method.

A positive result in at least one of the three tests for soil transmitted helminthiasis was observed in 83 of the 177 samples where it was possible to perform such determinations (46.9%; 95% CI 39.5 to 54.2). Among women, the prevalence was 52.6% (51/97; 95% CI 42.7% to 62.5%) and among men 40.0% (32/80; 95% CI 29.3% to 50.7%); the prevalence ratio was 1.31 (95% CI 0.9 to 1.8). In the 60/177 participants who declared temporarily going away from their communities, geohelminthiasis was found in 51.7% (95% CI 44.1% to 59.3%), whereas among those who did not go away, the corresponding value was 44.4% (95% CI 37.3% to 52.0%).

A total of 112 participants (58.3%; 95% CI 51.0 to 65.1)—with no significant differences by sex—declared the self-perceived presence of geohelminths in the last month. Table 1 shows the distributions of the presence, both measured and self-perceived, of soil transmitted helminthiasis, by age group. In the case of measured soil transmitted helminthiasis, no differences were found in terms of age groups (LR 1.53; p=0.47) (table 1). In contrast, for the perceived presence of parasites, differences were significant (LR 9.75; p<0.05), a linear association being found between perception of parasites and age, with older ages reporting a lower perception (80.0% to 48.1%) (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Measured and perceived prevalence of geohelminthiasis

| Age group (years) |

Presence of geohelminthiasis (measured) |

Presence of geohelminthiasis in past month (perceived) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 95% CI | n (%) | 95% CI | |

| 2–5 | 15/29 (51.7) | 34.5 to 69.0 | 24/30 (80.0) | 63.3 to 93.3 |

| 6–19 | 39/80 (48.8) | 37.5 to 58.8 | 51/85 (60.0) | 49.4 to 70.6 |

| ≥20 | 40/68 (58.8) | 47.1 to 70.6 | 37/77 (48.1) | 36.4 to 59.7 |

In the last month, 57.8% of participants reported having received preventive chemotherapy; in the age group 2–5 years, having received preventive chemotherapy in the last month was declared by 25/30 participants (83.3%); 56/85 (65.9%) in the age group 6–19 years and 30/77 (39.0%) in the age group 20 years and over (LR 22.37 p<0.05). This association was also linear (p<0.05).

Of the 104 participants who declared having received preventive chemotherapy in the last month and in whom the coproparasite assessment was performed, 46 (49.2%) were positive for the presence of helminths compared with 37/73 (50.7%) of those who had not received therapy (LR 0.72; p≥0.05). There were no differences in sex or age group.

The parasitic load of A lumbricoides varied from 24 to 18 792 epg, 50% having 408 epg or more. In the age group 2–5 years, median intensity was 600 epg, in those aged 6–19 it was 348 and in those aged 20 and over it was 384.

The intensity of infection among individuals aged 2–5 years was slight, among those aged 6–19 years it was slight in 90% and moderate in 10%, while in those aged 20 or over it was slight in 86.4% and moderate in 13.6%. The parasitic load of T trichuria ranged from 24 to 1080 epg, median 72, and levels by age group of 48, 72 and 60, respectively. The most common level of intensity of infection, in all age groups, was slight, with moderate levels being found in 2% of those aged 6–19 years.

Discussion

In this study, we found that 72.9% of households had at least one person infected by soil transmitted helminthiasis, and in 13% all members were infected. Also, we found a higher prevalence among households stating they did not boil water, where overcrowding was present as well as in families receiving any type of state subsidy, indicating worse sanitary conditions and greater poverty.

In marginalised populations, lacking sanitary conditions, one form of treating water for human consumption, in the home, is by boiling, thus preventing its contamination through contact with unwashed hands, dust rising from the bare earth floor, etc, even though the effectiveness of boiling may be questionable.19

This is an important aspect to consider because our results showed that community de-worming campaigns (57.8% received chemoprophylaxis in the last month) aimed at reducing or avoiding soil transmitted helminthiasis, without health education, are not sufficient, and must be accompanied by changes in sanitary conditions and poverty reduction policies and actions. In this sense, the lack of good water supplies and inadequate basic sanitation observed during the fieldwork, as well as a low participation of the communities themselves in basic sanitation activities, could be factors that impede the control of soil transmitted helminth infections.20–22

Additionally, the fact that receiving any kind of state subsidy and overcrowding were both associated with the prevalence of infection at the household level seems to confirm that it is not enough to treat this problem merely as a medical condition, and that it is necessary to improve the socioeconomic and sanitary conditions of the population. At the individual level, the high prevalence found was not differentiated by gender, age group, temporary migratory movement or by whether or not they had received chemoprophylaxis; this latter aspect was seen as a reflection of the community's situation, and not necessarily as an assessment of the efficacy of the chemoprophylaxis programme of the Public Health Ministry.

With respect to the results obtained in this community based study (global prevalence of 46.9% in samples where it was possible to perform the three determinations—direct observation, Kato–Katz method and analysis of the formol–ether concentrate), there are few references with which we can compare our findings as the majority of studies have been conducted in ‘captive’ populations, such as schoolchildren.23–25

The prevalence found in our study was much higher than values reported by several articles available in the scientific literature conducted in Ecuador, with an average prevalence of 18.9%.26 27 These studies formed part of a meta-analysis based on all publications related to the prevalence of soil transmitted helminth infection in South American countries. Nevertheless, our overall prevalence value was lower than that reported by a previous study carried out in groups of Shuar people (prevalence rate 65%) using the Kato–Katz method but without the antecedent of having received chemoprophylaxis.28

We found a large discrepancy between measured and perceived prevalence of geohelminthiasis, particularly for children <5 years of age, since in nearly 8 of every 10 cases the mother or guardian who responded perceived the presence of parasites whereas our findings halved this figure. This discrepancy could be explained by the fact that the national programme of preventive chemotherapy was conducted in these communities 4 weeks before our study. On the other hand, the prevalence in those aged over 19 years, who were also the least treated group, leads us to reflect that in these communities, the adult population could constitute a reservoir for infection and re-infection.

In Ecuador, epidemiological surveillance of soil transmitted helminth infections has not been considered either explicitly or as part of the group of neglected infectious diseases, and although the estimated prevalence of infection is high,16 currently the data are scarce. On the other hand, the Ecuadorian state publishes reports of its successful health campaigns for the control of neglected diseases, such as brucellosis, Chagas disease, urban rabies and onchocerciasis, and publicises the important increase in the budget for the control of neglected tropical diseases.29

The transmission rate of soil helminths remains high in regions such as the Amazonian southern border of Ecuador, in spite of the fact that in recent years member countries of the Pan American Health Organisation have celebrated regional conventions to address the intensification of control of these poverty related diseases.30

As part of this intensification of control, the WHO recommends that school based de-worming programmes include health hygiene education as a complementary measure, although the sustainability and long term impact of such education in hygiene does not appear to show encouraging results. These limitations in the control and epidemiological surveillance of helminthic infections could be solved with a long term intersectoral multidisciplinary programme.31 32

Finally, two limitations should be taken into account when interpreting our results. Given the age distribution of participants, the participation rate among working age men was very low, which could be attributable to two aspects: their absence from the community due to work and a tendency of people in this group to refuse to provide faecal samples. The other limitation is that the collection of a single stool sample probably means the prevalence was underestimated. Given the environmental conditions and geographical isolation, as well as a lack of resources, it was not possible to obtain more faecal samples.

Conclusions

All inhabitants of the two participating communities considered themselves to be at risk of soil transmitted helminth infection, despite having reported receiving preventive chemotherapy in the month prior to the study. For this reason, it is necessary to conduct holistic studies focusing on communities, and not on captive groups such as schoolchildren, with the object of proposing more suitable and effective strategies to control such infections.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Lino Arisqueta, Lizeth Cifuentes, Nicole Mora-Bowen, Gabriela León and Paola Lecaro to the field work of the study. Our thanks to Dave Macfarlane for help in developing the English language version of this article.

Footnotes

Contributors: NR-S, CO-R and MM wrote the statistical analysis plan, cleaned and analysed the data, and drafted and revised the paper. NR-S, MM, CS, JP and HJS-P provided guidance on data handling, contributed to the design of the analysis, provided interpretation of the data and reviewed the paper. CO-R, DV, CS and JP contributed to interpretation of the data and reviewed the paper. NR-S, JP, MM and HJS-P provided guidance on the conception of the work, interpretation of the data and reviewed the paper for content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Universidad Internacional del Ecuador Research Programme (I-EO-01-2014).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Universidad Central del Ecuador, and by the Ecuador Ministry of Public Health. Each study participant gave written informed consent and, in the case of children, was signed by their parents.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Addiss DG. Soil-transmitted helminthiasis: back to the original point. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15:871–2. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70095-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ojha SC, Jaide C, Jinawath N et al. Geohelminths: public health significance. J Infect Dev Ctries 2014;8:5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norman FF, Monge-Maillo B, Martínez-Pérez Á et al. Parasitic infections in travelers and immigrants: part II helminths and ectoparasites. Future Microbiol 2015;10:87–99. 10.2217/fmb.14.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prichard RK, Basáñez MG, Boatin BA et al. A research agenda for helminth diseases of humans: intervention for control and elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012;6:e1549 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta RS, Rodriguez A, Chico M et al. Maternal geohelminth infections are associated with an increased susceptibility to geohelminth infection in children: a case-control study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012;6:e1753 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malo-Serrano M, Malo-Corral N. Reforma de salud en Ecuador: nunca más el derecho a la salud como un privilegio. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica 2014;31:754–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.García B, Junior V.2014. Conditional cash transfer a mechanism for social inclusion in Ecuador: An Assessment of Bono de Desarrollo Humano/Programas de transferencias monetarias condicionadas, un mecanismo para la inclusión social en Ecuador: una evaluación del Bono de Desarrollo Humano. Sep 1 (cited 8 June 2016). http://repositorio.educacionsuperior.gob.ec/handle/28000/1408.

- 8.Mosquera GH. Repensar el cuidado a través de la migración internacional: mercado laboral, Estado y familias transnacionales en Ecuador*/Rethinking care through international migration: labour market, State and transnational families in Ecuador. Cuad Relac Laborales 2012;30:139. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censo. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010. http://www.inec.gob.ec/cpv/

- 10.WHO | PCT databank (cited 6 November 2015). http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/preventive_chemotherapy/sth/en/

- 11.Sánchez-Pérez HJ, Horna-Campos O, Romero-Sandoval N et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis in Latin America: patchwork studies reveal inequalities in its control–the cases of Chiapas (Mexico), Chine (Ecuador) and Lima (Peru) 2013. (cited 6 September 2013). http://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/43737/InTech-Pulmonary_tuberculosis_in_latin_america_patchwork_studies_reveal_inequalities_in_its_control_the_cases_of_chiapas_mexico_chine_ecuador_and_lima_peru_pdf

- 12.Encuesta de Condiciones de Vida, Ecuador. Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censo, Ecuador 2014. http://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/ECV/ECV_2015/ (accessed 2 Jun 2016).

- 13.Romero-Sandoval N, Escobar N, Utzet M et al. Sylvatic rabies and the perception of vampire bat activity in communities in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Cad Saude Publica 2014;30:669–74. 10.1590/0102-311X00070413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortiz-Rico C, Aldaz C, Sánchez-Pérez HJ et al. Conformance contrast testing between rates of pulmonary tuberculosis in Ecuadorian border areas. Salud Publica Mex 2015;57;496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO Expert Committee. Prevention and control of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2002;912:i–vi, 1–57, back cover. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menzies SK, Rodriguez A, Chico M et al. Risk factors for soil-transmitted helminth infections during the first 3 years of life in the tropics; findings from a birth cohort. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014;8:e2718 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moncayo AL, Vaca M, Oviedo G et al. Effects of geohelminth infection and age on the associations between allergen-specific IgE, skin test reactivity and wheeze: a case-control study. Clin Exp Allergy 2013;43:60–72. 10.1111/cea.12040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Speich B, Ali SM, Ame SM et al. Quality control in the diagnosis of Trichuris trichiura and Ascaris lumbricoides using the Kato-Katz technique: experience from three randomised controlled trials. Parasit Vectors 2015;8:82 10.1186/s13071-015-0702-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strunz EC, Addiss DG, Stocks ME et al. Water, sanitation, hygiene, and soil-transmitted helminth infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001620 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bain R, Cronk R, Wright J et al. Fecal contamination of drinking-water in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001644 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gyorkos TW, Maheu-Giroux M, Blouin B et al. Impact of health education on soil-transmitted helminth infections in schoolchildren of the Peruvian Amazon: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7:e2397 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo NC, Bogoch II, Blackburn BG et al. Comparison of community-wide, integrated mass drug administration strategies for schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis: a cost-effectiveness modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e629–38. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00047-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dana D, Mekonnen Z, Emana D et al. Prevalence and intensity of soil-transmitted helminth infections among pre-school age children in 12 kindergartens in Jimma Town, southwest Ethiopia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2015;109:225–7. 10.1093/trstmh/tru178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macchioni F, Segundo H, Gabrielli S et al. Dramatic decrease in prevalence of soil-transmitted helminths and new insights into intestinal protozoa in children living in the Chaco region, Bolivia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015;92:794–6. 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chammartin F, Scholte RGC, Guimarães LH et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infection in South America: a systematic review and geostatistical meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13:507–18. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70071-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pullan RL, Smith JL, Jasrasaria R et al. Global numbers of infection and disease burden of soil transmitted helminth infections in 2010. Parasit Vectors 2014;7:37 10.1186/1756-3305-7-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cepon-Robins TJ, Liebert MA, Gildner TE et al. Soil-transmitted helminth prevalence and infection intensity among geographically and economically distinct Shuar communities in the Ecuadorian Amazon. J Parasitol 2014;100:598–607. 10.1645/13-383.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikolay B, Mwandawiro CS, Kihara JH et al. Understanding heterogeneity in the impact of National Neglected Tropical Disease Control Programmes: evidence from school-based deworming in Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9:e0004108 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cartelle Gestal M, Holban AM, Escalante S et al. Epidemiology of tropical neglected diseases in Ecuador in the last 20 years. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0138311 10.1371/journal.pone.0138311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thériault FL, Blouin B, Casapía M et al. Sustaining a hygiene education intervention to prevent and control geohelminth infections at schools in the Peruvian Amazon 2015. (cited 15 Jun 2016). http://iris.paho.org/xmlui/handle/123456789/18385 [PubMed]

- 31.Panic G, Duthaler U, Speich B et al. Repurposing drugs for the treatment and control of helminth infections. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 2014;4:185–200. 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2014.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabrie JA, Rueda MM, Canales M et al. School hygiene and deworming are key protective factors for reduced transmission of soil-transmitted helminths among schoolchildren in Honduras. Parasit Vectors 2014;7:354 10.1186/1756-3305-7-354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]