Abstract

Objectives

Pregnancy may cause changes in drug disposition, dose requirements and clinical response. For lithium, changes in disposition during pregnancy have so far been explored in a single-dose study on 4 participants only. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of pregnancy on serum levels of lithium in a larger patient material in a naturalistic setting.

Design

A retrospective observational study of patient data from 2 routine therapeutic drug monitoring services in Norway, linked to the Medical Birth Registry of Norway.

Setting

Norway, October 1999 to December 2011.

Measurements

Dose-adjusted drug concentrations of lithium during pregnancy were compared with the women's own baseline (non-pregnant) values, using a linear mixed model.

Results

Overall, coupling 196 726 serum concentration measurements from 54 393 women to the national birth registry identified 25 serum lithium concentration analyses obtained from a total of 14 pregnancies in 13 women, and 63 baseline analyses from the same women. Dose-adjusted serum concentrations in the third trimester were significantly lower than baseline (−34%; CI −44% to −23%, p<0.001).

Conclusions

Pregnancy causes a clinically relevant decline in maternal lithium serum concentrations. In order to maintain stable lithium concentrations during the third trimester of pregnancy, doses generally need to be increased by 50%. Individual variability in decline implies that lithium levels should be even more closely monitored throughout pregnancy and in the puerperium than in non-pregnant women to ensure adequate dosing.

Keywords: PSYCHIATRY, CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We used a large sample size from a naturalistic setting.

The patients' physicians were contacted to ensure correct information regarding lithium dose used before, during and after pregnancy.

Linkage to the national birth registry ensured precise information regarding gestational week for each sample obtained during pregnancy.

We did not have access to clinical data, neither regarding the clinical condition of the mother, drug adherence, nor pregnancy outcome.

Introduction

The management of bipolar disorder during pregnancy and in the puerperium is a medical challenge. On the one hand, lithium is considered to be one of the key agents to treat and prevent manic and depressive episodes occurring in bipolar disorder.1 2 On the other hand, lithium use has been associated with teratogenic effects, in particular a serious congenital heart defect known as Ebsteins's anomaly.3–5 Although the absolute risk of this anomaly is low and recent studies have failed to find statistically significant evidence of an association with lithium use,2 considerable uncertainty still remains regarding its potential teratogenicity.2 6

Unfortunately, pregnancy does not protect against new manic or depressive episodes. Women with bipolar disorder have a more than 50% risk of relapse of symptoms during the pregnancy and early postpartum period, and women who discontinue mood stabilisers before or during pregnancy are at particularly high risk.5 7–9 Psychiatric decompensation during pregnancy can affect the mother as well as the fetus and neonate, and may be complicated by poor prenatal care, insomnia, substance abuse, poor bonding with the baby, inability to care for the infant, obsessions regarding the baby, delusions, hallucinations, suicide and infanticide.10 Thus, the use of a mood stabiliser during pregnancy is often a necessity. Since some treatment options (in particular, valproate) are known teratogenic agents, and others (such as lamotrigine or antipsychotics) may be less efficient, lithium is considered by many authors to offer the best efficacy/safety ratio for bipolar disorder in pregnancy.1 3 8 11–13 Thus, for women with a good treatment response to lithium, maintained use during pregnancy might represent the best risk–benefit option.

When a decision has been made to start or continue lithium treatment during pregnancy, there is a paucity of data to ensure appropriate dosing. Physiological changes in pregnancy are known to cause changes in drug disposition and alter serum drug levels.14–16 For lithium, our current knowledge on lithium disposition in pregnancy is confined to a small experimental study, reporting an ∼50% decrease in lithium concentrations in four participants in the third trimester.17 The issue clearly needs to be investigated in larger patient materials. The aim of this study was to elucidate to what extent pregnancy affects serum concentrations of lithium in a large target population in a naturalistic setting.

Methods

Therapeutic drug monitoring data

Serum concentration data for lithium were collected from the two largest therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) services for psychotropic drugs in Norway, at the Department of Clinical Pharmacology at St Olav University Hospital in Trondheim and at the Center for Psychopharmacology at Diakonhjemmet Hospital in Oslo. In addition to the measured lithium concentrations, the TDM databases contained information about the prescribed lithium dose, time of last drug intake, time of blood sampling, and types and doses of concomitant drugs.

The Medical Birth Registry of Norway

The Medical Birth Registry of Norway (MBRN) is a population-based registry containing information on all births in Norway since 1967.18 The registry is based on compulsory notification of every birth or late abortion from 12 completed weeks of gestation onwards. The report form is usually filled in by a midwife and includes identification of the parents, maternal diagnoses before and during pregnancy, and date of delivery and length of pregnancy as well as other information regarding the mother and infant.

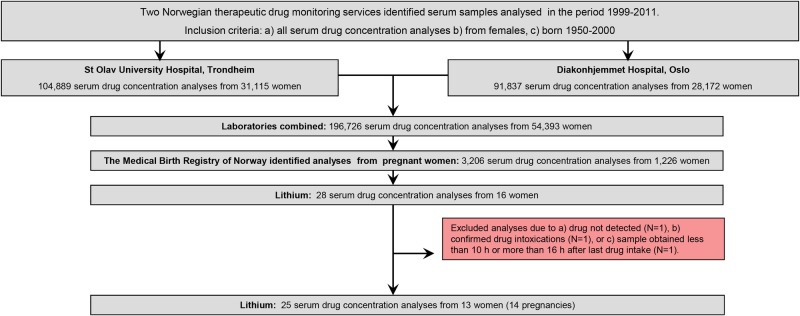

Data linkage and available data

First, a combined laboratory TDM file was created, containing all serum concentration measurements (for any drug) in the period October 1999 to December 2011 for all women of reproductive age (ie, those born in the years 1950–2000). The file consisted of a total of 196 726 analyses from 54 393 women (figure 1). Using the unique 11-digit identification number assigned to every individual living in Norway, the MBRN could identify all pregnant women in the data set. By applying this procedure, 3206 analyses from 1226 pregnant women were identified (figure 1). For the current study, we retrieved the following information: the personal identification number, the measured lithium serum concentration, time of last dose, time of blood sampling, drug dose, concomitant drug use, other clinical information, name of the responsible physician, gestational week at the time of sampling (determined by ultrasound if available, otherwise by last menstruation) and date of delivery.

Figure 1.

Lithium samples obtained during pregnancy: sample identification and inclusion flow.

Inclusion criteria

The basis of this study is all samples analysed for lithium during pregnancy. In total, 28 analyses from 16 pregnant women were available (figure 1). Analyses were excluded if (1) no drug was detected, (2) the sample was obtained as a result of drug intoxication, or (3) the sample was obtained less than 10 hours or more than 16 hours after last oral drug intake. If the requisition form lacked information on drug dose, the authors contacted the responsible physician, who obtained this information from the medical record. The final data set consisted of 25 serum drug concentrations from 13 women (figure 1). The study population is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

The study population

| Number of serum lithium concentration analyses available |

Maternal age at delivery (years) | Comedication during pregnancy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During pregnancy | First month after delivery | At baseline | |||

| Patient 1 | 2+3* | 1 | 19 | 34/39* | Perphenazine |

| Patient 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 31 | Valproic acid, escitalopram, mianserin, chlorprothixene |

| Patient 3 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 32 | Alprazolam |

| Patient 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 32 | Lamotrigine |

| Patient 5 | 1 | 3 | 15 | 27 | – |

| Patient 6 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 30 | Lamotrigine, quetiapine |

| Patient 7 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 30 | Risperidone |

| Patient 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 40 | Zopiclone, quetiapine, alimemazine |

| Patient 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 30 | Lamotrigine, olanzapine |

| Patient 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 28 | – |

| Patient 11 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 34 | Lamotrigine, quetiapine |

| Patient 12 | 1 | 0 | 13 | 37 | Quetiapine |

| Patient 13 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 36 | – |

| Total | 25 | 4 | 63 | Mean: 32.9 | |

*Patient 1 contributed with samples from two pregnancies.

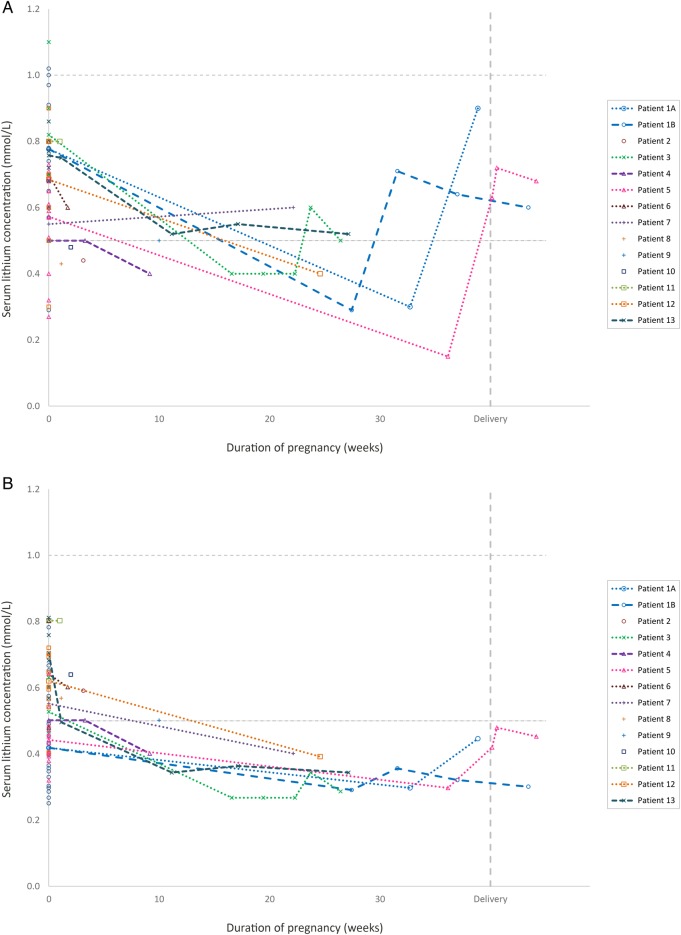

Control samples

Having identified the pregnant women and their individual pregnancy periods in the extracted data file, we used the original TDM databases to retrieve serum concentration measurements before and after pregnancy from the same women, to serve as baseline observations. Identical inclusion and exclusion criteria as presented above were used, and 67 analyses were identified (table 1). Four of these were from the first month after delivery (ie, in the ‘returning to baseline’ phase). These analyses were not used in the statistical model, but are included in figure 2. The remaining 63 analyses were used for the statistical comparisons.

Figure 2.

The serum lithium concentrations across pregnancy in the 13 patients studied. Figure (A) shows the measured serum concentrations (not adjusted to dose) for each participant of the study. Figure (B) shows the same observations after being adjusted to a lithium dose of 24 mmol/day. Samples drawn from the same women in a non-pregnant state (baseline values) are shown as pregnancy week 0. Delivery is set to pregnancy week 40. Thus, for a woman who gave birth in week 38, a sample drawn t weeks after delivery would be shown t weeks to the right of the vertical delivery line. The horizontal dashed lines represent the commonly used reference serum concentration range for lithium (0.5–1.0 mmol/L).

Determination of serum lithium concentrations

Serum lithium concentrations were measured using a direct ion-selective electrode method (Cobas Integra 400 Plus (at St Olav University Hospital) or 9180 Electrolyte Analyzer (at Diakonhjemmet Hospital), both from Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany).19 20 Concentrations were reported in mmol/L with two significant digits after the decimal point. The lower limits of quantification were 0.16 mmol/L at St Olav University Hospital and 0.10 mmol/L at Diakonhjemmet Hospital.

Data analysis

Serum lithium concentrations were divided by the daily dose (in mmol) used by the woman at the time of sampling, providing a serum concentration/dose ratio, and then multiplied by 24 mmol, which is the defined daily dose21 for lithium, that is, the assumed average maintenance dose per day for lithium used for bipolar disorder in adults. This procedure provides an intraindividually and interindividually comparable concentration. All concentrations presented and discussed in this article, including tables and figures, are dose-adjusted to the 24 mmol/day dose, unless otherwise specified.

Since the concentration distributions were found to be heavily right-skewed, the natural logarithm of the concentrations was employed as the outcome variable in the statistical analysis to achieve near normality. Since multiple measurements were available from the same patient, a linear mixed model was used. The model assumes that each individual patient possesses a random intercept (ie, an individual ‘offset’) in addition to being affected by the gestational week at the time of sampling. Baseline measurements were set to gestational week 0 in the model. This way, the effect of gestational week on lithium concentration compared with baseline is estimated. Specifically, the concentration in gestational week t is calculated by using the following equation: serum concentration (week t)=ebaseline estimate+(t×gestational week estimate).

All model parameters, including variance components, were estimated by the method of maximum likelihood using the STATA V.13 command ‘mixed’. Data are presented as means with 95% CIs. p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 provides an overview of all participants, analyses and pregnancies included in the study. The mean duration of pregnancy (±SD) was 272±19 days. The mean maternal age at delivery was 32.9±3.8 years. The mean age of the women at the time of baseline sampling was 34.1±4.0 years.

The estimated loge serum lithium concentration (in mmol/L) at day 0 was −0.632 (CI −0.740 to −0524, p<0.001) and the change for each gestational week was −0.012 (CI −0.017 to −0.008; p<0.001). Table 2 shows calculated concentrations for each mid trimester (pregnancy weeks 6, 20 and 34). Serum lithium concentrations declined throughout pregnancy, and the mid third trimester (gestational week 34) concentration was 34% lower than at baseline (CI −44% to −23%, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Estimated serum lithium concentrations across pregnancy for a dose of 24 mmol/day

| Conc (mmol/L) | 95% CI (mmol/L) | Change from baseline | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (week 0) | 0.53 | 0.48 to 0.59 | – | – |

| 1st trimester (week 6) | 0.49 | 0.48 to 0.51 | −7% | −10% to −4% |

| 2nd trimester (week 20) | 0.41 | 0.38 to 0.46 | −22% | −29% to −14% |

| 3rd trimester (week 34) | 0.35 | 0.30 to 0.41 | −34% | −44% to −23% |

Conc, concentration.

Individual concentrations related to gestational week, as well as when the women were not pregnant, are shown in figure 2. Regarding changes in lithium levels following delivery, we had observations from two participants only, shown to the right in figure 2. Patient #5 had samples obtained at 1, 4 and 29 days following delivery, and there was a steep increase in dose-adjusted lithium levels from the last observation in the third trimester to day 4 following delivery. Another participant, patient #1, had approximately the same lithium serum level at day 24 following delivery, as during the third trimester (figure 2B).

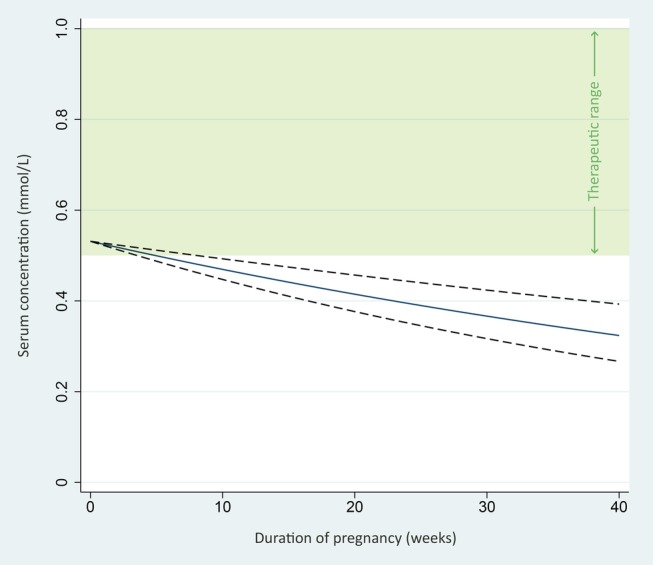

Figure 3 provides the regression line from our observations with 95% confidence limits showing the expected serum concentrations for a woman using a lithium dose of 24 mmol/day dose across pregnancy.

Figure 3.

Expected lithium serum concentrations in pregnancy with a daily dose of 24 mmol lithium. The figure shows the expected serum lithium concentrations across pregnancy for a woman using a 24 mmol daily dose. The regression line (solid line) and 95% confidence limits (dashed lines) are based on the 88 observations in the 13 participants of our study. The green area represents the commonly used reference serum concentration range for lithium (0.5–1.0 mmol/L).

Discussion

This study, including data from 14 pregnancies, is the largest until now on lithium disposition in pregnancy. We found that serum lithium concentrations decrease during pregnancy, with levels in the third trimester on average reduced by 34% compared with non-pregnant levels. Since lithium is not subject to metabolic transformation and is almost exclusively excreted renally,1 the decline in serum concentration is likely to be caused by increased renal clearance in pregnancy, as has been suggested previously.22 23 Increased total body water in pregnancy is not expected to affect the serum concentration of lithium at steady state, in contrast to the initial serum concentration achieved after a single dose, as total clearance is the primary determinant of the serum concentration at steady state.14

Our study manifests the observations reported by Schou et al,22 recruiting four physically and mentally healthy pregnant women to take a small (16.2 mmol Li+) single dose of lithium carbonate in the third trimester and then once again 6–7 weeks after delivery. They found that the lithium clearance in the third trimester was almost double the mean non-pregnant clearance, causing a 50% reduction in lithium serum levels. Our study also demonstrated a similar decline in serum lithium levels, but to a slightly lower degree. The increased lithium clearance seems to parallel that of creatinine: creatinine clearance starts to increase in the first trimester and peaks in mid-pregnancy, with an average increase of 37–45%.14

The observed decline in lithium levels is likely to be of clinical relevance. If concentrations fall too low, the patient is at risk of treatment failure. Thus, a woman having a stable condition using the lowest efficient lithium dose at the start of the pregnancy may risk destabilisation when the drug levels decline. In our study, all pregnancies in which samples were drawn in the third trimester (3 pregnancies in 2 women) had serum lithium levels of 0.3 mmol/L or lower, concentrations that are considered to be subtherapeutic regardless of bipolar type and phase.24 In all these cases, immediate dose increases were undertaken (figure 2A). Although we lack clinical data, one might suspect that the physicians responsible for these women were not aware of the anticipated decline in lithium levels in pregnancy.

As shown in figure 3, the estimated concentrations for a woman using the defined daily dose21 of lithium (ie, 24 mmol/day) will be within the therapeutic range (shown in green) at the beginning of the pregnancy, but fall below therapeutic levels throughout pregnancy. It is also important to note that there are individual differences regarding the decline in lithium serum levels, as illustrated in figure 2B.

Our study has too few observations to draw firm conclusions as to how fast lithium levels return to non-pregnant levels following childbirth. One patient had an immediate increase in lithium serum levels following childbirth; another apparently had not (figure 2B). However, we know that the glomerular filtration rate normalises rapidly following delivery,25 and lithium levels are believed to show parallel changes.26 Thus, if the lithium dose has been increased during pregnancy, it should be reduced at the time of delivery to avoid intoxication.25 26 Since there appear to be variations in the extent of changes in lithium levels in pregnancy (figure 2B), adjustments in lithium doses during pregnancy and the puerperium should be based on frequent determinations of the serum lithium concentrations.

This study has some limitations that need to be addressed. First, since we did not have access to clinical data, we do not know whether the reduced concentrations caused clinical deterioration, although we do know that patients with concentrations below the recommended therapeutic range carry a higher risk of therapeutic failure.24 Second, it is unknown to what degree patients were adherent to the prescribed medication. Non-adherence is a particular challenge during pregnancy.27 However, analyses with a serum concentration of zero (n=1, figure 1) were excluded from the study, and we consider it to be unlikely that an increasing degree of partial non-adherence as pregnancy proceeds could be the reason for the observed gradual decline in the serum levels (figures 2 and 3).

On the other hand, this study also has some strengths, the most obvious being the large sample size. Owing to the ethical issues involved in clinical drug trials during pregnancy,28 29 and the apparently low number of women using lithium while pregnant,6 30 retrospective studies of samples taken in a naturalistic setting are often the only available tool to obtain information on drug disposition in pregnancy. Owing to the variability often seen in observational studies, a large sample size is crucial, such as in this study, with data from two large routine TDM services over a time span of 12 years included. It is also a strength that we could link the TDM data to a national birth registry, thereby allowing precise identification of pregnant women in the data set, and making misclassification of gestational week unlikely.

Decisions regarding medication use during pregnancy will always require weighing of benefits against risks. For lithium, these judgements may be difficult, since some uncertainty still remains regarding its teratogenicity.2 6 Nonetheless, lithium is considered by many authors to offer the best efficacy/safety ratio for bipolar disorder in pregnancy,1 3 8 11–13 and for many pregnant patients its use is necessary to give the mother and child a stable and secure start together. Our study sheds more light on how lithium should be dosed in these patients.

To conclude, we found a gradual decline in lithium serum concentrations throughout pregnancy, with lithium levels in the third trimester being 34% lower than the non-pregnant levels, necessitating a 50% increase in the lithium dose to maintain stable levels. After delivery, serum levels most likely return to non-pregnant levels within a few days. Our study supports the recommendation that serum lithium levels should be monitored even more closely during pregnancy and the puerperium than in non-pregnant women.31 It is also important that prescribers are made aware of the anticipated increase in lithium dose requirement in pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Simon Thoresen, Ludvig Johannesen and Magnild Hendset for their help on extracting and preparing the data from the therapeutic drug monitoring databases.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Andreas Westin @Andreas_Westin

Contributors: AAW, EM and OS designed the study protocol, and participated in the coordination and management of the study. AAW, MB and MA performed the data acquisition from the therapeutic drug monitoring databases. AAW and ES performed the statistical analysis, and all authors participated in the interpretation and discussion of the results. AAW wrote the first manuscript draft, and all authors revised it critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or non-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (Data Protection Official), the Norwegian Directorate of Health, and the Medical Birth Registry of Norway (MBRN). The need for informed consent was waived by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (Ref. No. 08/8544–2) and the Norwegian Directorate of Health (Ref. No. 08/10184), according to Norwegian legislation.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Oruch R, Elderbi MA, Khattab HA et al. Lithium: a review of pharmacology, clinical uses, and toxicity. Eur J Pharmacol 2014;740:464–73. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.06.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K et al. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2012;379:721–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61516-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chisolm MS, Payne JL. Management of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy. BMJ 2016;532:h5918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsen ER, Damkier P, Pedersen LH, et al Use of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy and breast-feeding. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2015;(445):1–28. 10.1111/acps.12479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grover S, Avasthi A. Mood stabilizers in pregnancy and lactation. Indian J Psychiatry 2015;57(Suppl 2):S308–23. 10.4103/0019-5545.161498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCrea RL, Nazareth I, Evans SJ et al. Lithium prescribing during pregnancy: a UK primary care database study. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0121024 10.1371/journal.pone.0121024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viguera AC, Whitfield T, Baldessarini RJ et al. Risk of recurrence in women with bipolar disorder during pregnancy: prospective study of mood stabilizer discontinuation. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:1817–24; quiz 923 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosso G, Albert U, Di Salvo G et al. Lithium prophylaxis during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with lithium-responsive bipolar I disorder. Arch Womens Ment Health 2016;19:429–32. 10.1007/s00737-016-0601-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Florio A, Forty L, Gordon-Smith K et al. Perinatal episodes across the mood disorder spectrum. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:168–75. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan SJ, Fersh ME, Ernst C et al. Bipolar disorder in pregnancy and postpartum: principles of management. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2016;18:13 10.1007/s11920-015-0658-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deiana V, Chillotti C, Manchia M et al. Continuation versus discontinuation of lithium during pregnancy: a retrospective case series. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2014;34:407–10. 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergink V, Kushner SA. Lithium during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171:712–15. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14030409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA et al. Reproductive safety of second-generation antipsychotics: current data from the Massachusetts General Hospital National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:263–70. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tasnif Y, Morado J, Hebert MF. Pregnancy-related pharmacokinetic changes. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2016;100:53–62. 10.1002/cpt.382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pariente G, Leibson T, Carls A et al. Pregnancy-associated changes in pharmacokinetics: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002160 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horton S, Tuerk A, Cook D et al. Maximum recommended dosage of lithium for pregnant women based on a PBPK model for lithium absorption. Adv Bioinform 2012;2012:352729 10.1155/2012/352729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grandjean EM, Aubry JM. Lithium: updated human knowledge using an evidence-based approach. Part II: clinical pharmacology and therapeutic monitoring. CNS Drugs 2009;23:331–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irgens LM. The Medical Birth Registry of Norway. Epidemiological research and surveillance throughout 30 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:435–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cobas Integra 400 Plus. http://www.cobas.com/home/product/clinical-and-immunochemistry-testing/cobas-integra-400-plus.html (accessed 5 Dec 2016).

- 20.Roche Diagnostics AVL 9180 Series Electrolyte Analyzers. https://www.fishersci.com/shop/products/roche-diagnostics-avl-9180-series-electrolyte-analyzers-roche-9180-series-electrolyte-analyzer/avlgd5043 (accessed 20 Dec 2016).

- 21.WHO Collaborative Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD Index 2016. http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ (accessed Dec 2016).

- 22.Schou M, Amdisen A, Steenstrup OR. Lithium and pregnancy. II. Hazards to women given lithium during pregnancy and delivery. BMJ 1973;2:137–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blake LD, Lucas DN, Aziz K et al. Lithium toxicity and the parturient: case report and literature review. Int J Obstet Anesth 2008;17:164–9. 10.1016/j.ijoa.2007.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malhi GS, Tanious M, Das P et al. The science and practice of lithium therapy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2012;46:192–211. 10.1177/0004867412437346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deligiannidis KM. Therapeutic drug monitoring in pregnant and postpartum women: recommendations for SSRIs, lamotrigine, and lithium. J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71:649–50. 10.4088/JCP.10ac06132gre [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schou M. Lithium treatment during pregnancy, delivery, and lactation: an update. J Clin Psychiatry 1990;51:410–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsui D. Adherence with drug therapy in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Int 2012;2012:796590 10.1155/2012/796590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheffield JS, Siegel D, Mirochnick M et al. Designing drug trials: considerations for pregnant women. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59(Suppl 7):S437–44. 10.1093/cid/ciu709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Briggs GG, Polifka JE, Wisner KL et al. Should pregnant women be included in phase IV clinical drug trials? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:810–15. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersen I, McCrea RL, Sammon CJ et al. Risks and benefits of psychotropic medication in pregnancy: cohort studies based on UK electronic primary care health records. Health Technol Assess 2016;20:1–176. 10.3310/hta20230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192 (accessed Jan 2017).