Abstract

Background

The majority of people with dementia have other long-term diseases, the presence of which may affect the progression and management of dementia. This study aimed to identify subgroups with higher healthcare needs, by analysing how primary care consultations, number of prescriptions and hospital admissions by people with dementia varies with having additional long-term diseases (comorbidity).

Methods

A retrospective cohort study based on health data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) was conducted. Incident cases of dementia diagnosed in the year starting 1/3/2008 were selected and followed for up to 5 years. The number of comorbidities was obtained from a set of 34 chronic health conditions. Service usage (primary care consultations, hospitalisations and prescriptions) and time-to-death were determined during follow-up. Multilevel negative binomial regression and Cox regression, adjusted for age and gender, were used to model differences in service usage and death between differing numbers of comorbidities.

Results

Data from 4999 people (14 866 person-years of follow-up) were analysed. Overall, 91.7% of people had 1 or more additional comorbidities. Compared with those with 2 or 3 comorbidities, people with ≥6 comorbidities had higher rates of primary care consultations (rate ratio (RR) 1.31, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.36), prescriptions (RR 1.68, 95% CI 1.57 to 1.81), and hospitalisation (RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.44 to 1.83), and higher risk of death (HR 1.56, 95% CI 1.37 to 1.78).

Discussion

In the UK, people with dementia with higher numbers of comorbidities die earlier and have considerably higher health service usage in terms of primary care consultations, hospital admissions and prescribing. This study provides strong evidence that comorbidity is a key factor that should be considered when allocating resources and planning care for people with dementia.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, comorbidity, multimorbidity, HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT, Service Use

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to examine the association between comorbidities and service usage in the UK dementia population.

A relatively large, representative number of incident cases of dementia were sampled with insight into primary and secondary care service usage.

Provides evidence of the importance of considering comorbidities when planning dementia care and healthcare resource allocation in the UK.

There is no standard set of codes to identify comorbidities increasing the risk of misclassification.

Outcome measures are simple and do not capture the full nature of care provided.

Introduction

The provision of care to the rising number of people living with dementia remains a public health challenge for health systems worldwide. In the UK, there are ∼850 000 people who are currently living with dementia1 with estimated care costs equivalent to £32 250 per person per year.2 Those diagnosed with dementia have significantly higher community-based primary care physician (general practitioner, GP) consultation rates when compared with those with no dementia.3 However, there is significant variation that could be explained by patterns of comorbidity.4–6 Dementia can complicate the management of comorbid conditions7 and comorbidities or their treatment can accelerate the progression of dementia.8 9 Identifying which groups have the greatest need for healthcare is essential to plan effective dementia care.10

Multimorbidity—the presence of two or more chronic health conditions—is highly prevalent in the population with dementia. It has been estimated that 95% of those with dementia have another chronic disease in the Scottish population.11 In the USA, the Center for Health Care Strategies found heterogeneous hospitalisation rates and care costs (excluding long-term care) based on comorbidity patterns, with higher rates in those with additional psychiatric conditions other than dementia.12 In the UK, a strong association has been observed between multimorbidity and both primary care consultations and unplanned hospitalisation in the general population.13 However, it is uncertain to what degree these findings can be extrapolated to the dementia population.

Understanding health service usage rates is necessary to inform the care needs of the dementia population. The number of comorbidities could potentially be used to inform the type and place of dementia care needed and guide healthcare resource allocation. Using electronic health records, this study aimed to describe the distribution of comorbidity and estimate its impact on primary care consultations, prescriptions and hospitalisations in the UK dementia incident population. As secondary objectives, the impact of the number of comorbidities over risk of death and the role of specific comorbidities was also assessed.

Methods

Study design and setting

A population-based retrospective cohort study was conducted using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD).14 CPRD provides anonymous data from electronic health records of 674 primary care practices in the UK. In 2013, it included 4.4 million active participants representing 6.9% of the total UK population.15 This data set contains routinely collected information on demographics, diagnoses, medications and tests that can be tracked back to 1987.14 The validity of CPRD for the identification of chronic conditions has been described as high,15 16 with positive predictive values for dementia that range between 80% and 90%.17 As the vast majority of the UK population is registered with a GP, CPRD data are generally representative of the population as a whole. Primary care data were linked to administrative Hospital Episodes Statistics (HES) data to identify secondary care admissions.

Participants, exposure, outcomes and covariates

Incident cases of dementia diagnosed between 1 March 2008 and 28 February 2009 with at least 3 months of follow-up were included in this study. Cases were identified using 65 read codes that describe unspecified dementia or any dementia subtype were used to identify cases (see online supplementary appendix 1). Read codes are the standard clinical terminology used by CPRD and UK primary care more generally, and are more extensive than the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 system covering additional areas such as administrative processes. Our set of codes was based on two published dementia lists,18 19 augmented by a manual search by an appropriately experienced clinician of all read terms within CPRD to identify any additional codes that fitted the case definition. The minimum 3 months follow-up period aimed to decrease the risk of confounding due to individuals being in the final weeks of life; during this period, consultation rates are known to be very high and dependent on other variables not measured reliably in this study (eg, access to palliative care).20

bmjopen-2016-012546supp_appendix1.pdf (93.2KB, pdf)

We defined comorbidity as the presence of one or more chronic health conditions, excluding dementia itself as the index condition, based on the list of long-term conditions in UK primary care published by Barnett et al.11 The clinical relevance and appropriateness of five of the comorbidities in this list was questioned in the context of the current work, and a decision therefore taken to drop or merge them, resulting in a final list of 34 chronic conditions excluding dementia itself (see online supplementary appendix 2). Corresponding Read codes (including diagnostic or administrative codes, and where relevant, medication codes) for each condition were drawn from existing published code lists (identified from literature review and the code repositories in clinicalcodes.org and caliberresearch.org) and manual searching of all possible CPRD codes. Two experienced clinicians reviewed each set of codes, with disagreements settled through discussion with a further two clinicians. The prevalence of long-term conditions based on the selected codes was checked in a separate, random CPRD sample of 300 000 adults, and codes were reviewed and revised if necessary where differences in prevalence were observed compared with established published figures.

bmjopen-2016-012546supp_appendix2.pdf (170.9KB, pdf)

Information on service usage (counts of primary care consultations, hospitalisation and numbers of medicines prescribed) and time-to-death were obtained during the follow-up period. Primary care practice consultations were defined as face-to-face and telephone consultations, including unscheduled care, with multiple encounters on a single day only counted once; the exact classification used is detailed in online supplementary appendix 3. Hospital inpatient encounters were determined using CPRD's integrated HES data, based on dates of discharge for all routine and unplanned hospital admissions, irrespective of diagnosis. Prescribing was based on a simple count of all prescriptions issued during the follow-up period; duration of treatment was ignored, and multiple prescriptions for the same item were counted only once. Additionally, time-to-death obtained from the CPRD data was analysed as a secondary outcome to inform differences in mortality risk between exposure groups.

bmjopen-2016-012546supp_appendix3.pdf (46.8KB, pdf)

Finally, information on age, gender, socioeconomic status (Index of Multiple Deprivation), primary care practice and dementia medications (acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine) were obtained for adjustment.

Sample size

A minimum sample size of at least 1260 persons was required to detect a clinically relevant increase of 15% in primary care consultations, with 90% power and a significance level of 1%. Assuming a baseline rate of 16 consultations per person per year3 and an average follow-up of 2.5 years,20 we needed a sample of at least 77 participants. To account for participants being clustered within primary care practices, the sample size was inflated using the design effect formula21 with an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.068.21 Previous research has shown that when patients with dementia are categorised into groups by their number of comorbidities (none, one, two, three or more comorbidities), the group of patients with no comorbidities is the least prevalent, and expected to be around 5% in the study population.11 We further inflated the sample size to ensure adequate representation of this smaller group.

Statistical analysis

Participants were followed from first date of dementia diagnosis for up to 5 years, or earlier when death or transfer-out of CPRD occurred. Transfer-out of CPRD (loss of follow-up) was considered a non-informative event and participants were censored when this happened. Participants were categorised into exposure groups based on the number of comorbidities: low (dementia alone or only 1 additional comorbidity), moderate (2–3 additional comorbidities), high (4–5 additional comorbidities) or very high (6 or more additional comorbidities). To conduct a clinically meaningful analysis, the group with the highest prevalence (moderate, 2–3 additional comorbidities) was selected as the reference group.

Descriptive statistics including prevalence, medians and IQR were used to describe the distribution of comorbidity in the study population. Using Stata V.13.1, a multilevel negative binomial regression model accounting for different follow-up times was fitted to obtain rate ratios (RR) between the exposure groups for the three service usage outcomes. Multivariable regression was employed to adjust for key confounders, and potential clustering of outcome by primary care practice was accounted for by inclusion of a random intercept in the model (second level). Adjusted RRs are reported together with their 95% CIs. No significant interactions between the exposure with age or gender were found, hence non-stratified estimates of association are presented.

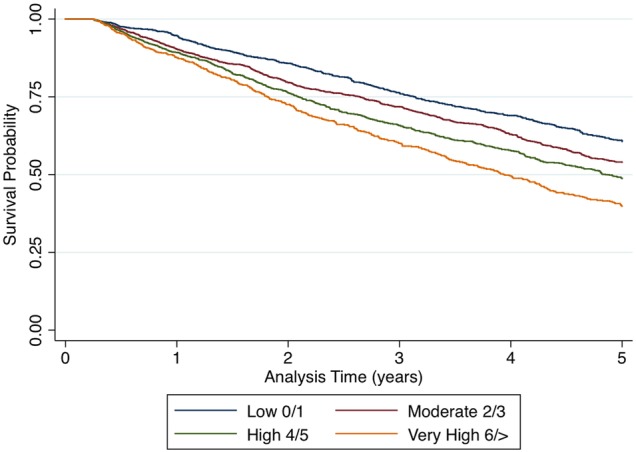

As secondary objectives RRs between comorbidities with a 10% or greater prevalence and service usage outcomes were calculated using a similar multivariable negative binomial regression, adjustment was made for age, gender and count of comorbidities with prevalence <10%. In addition, a multivariable Cox regression model was fitted to assess the association between time-to-death from diagnosis and number of comorbidities. The proportional hazard was evaluated using log-log plots and the Schoenfeld residuals test. HRs together with their 95% CIs are reported, with results graphically described using a Kaplan-Meier plot.

Linkage to deprivation and hospitalisation data is not available for around two-fifths of patients in CPRD, due to data sharing restrictions in some primary care practices. Given this high degree of missingness, imputation was not undertaken and a complete case analysis was conducted for these data.

Results

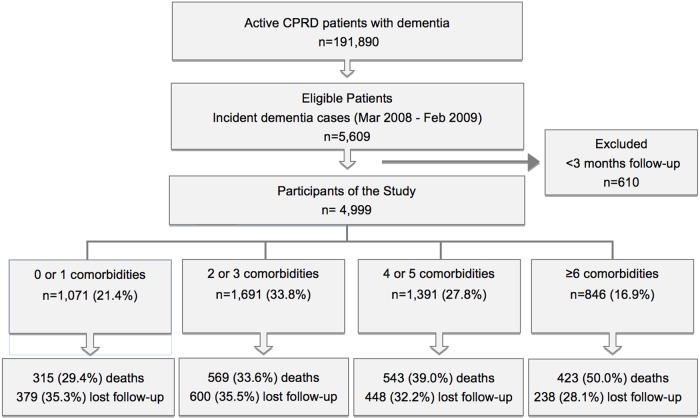

A total of 4999 people with dementia from 581 practices were included in this study (figure 1). Mean follow-up time was 2.97 years providing a total of 14 866 person-years at risk. In total, 1665 (33.3%) participants were transferred out of CPRD during the follow-up period, with the most frequent reason for this being transfer to another practice (73.8%). Those who were transferred out were older (83 vs 79 years) and had a higher mean number of comorbidities (3.6 vs 3.1) with no differences in gender. Mean age was 81.4 years (SD 8.1) and the proportion of females was 65.0%. Increasing age and socioeconomic deprivation were observed in those with higher numbers of comorbidities (table 1). Linked hospital admission data were only available on 2853 patients; there were no clinically significant differences in age or gender distributions of this smaller subset of patients.

Figure 1.

Flow of the participants through the study. CPRD, Clinical Practice Research Datalink.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by number of comorbidities

| Number of comorbidities |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low 0 or 1 | Moderate 2 or 3 | High 4 or 5 | Very high ≥6 | |

| Number of cases (%) | 1071 (21.4%) | 1691 (33.8%) | 1391 (27.8%) | 846 (16.9%) |

| Female (%) | 67.0% | 66.8% | 63.6% | 61.4% |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 79.5 (9.2) | 81.4 (7.8) | 82.0 (7.8) | 82.7 (7.0) |

| Age group (%) | ||||

| <75 years | 26.2 | 18.3 | 16.4 | 11.9 |

| 75–79 years | 21.8 | 19.3 | 18.0 | 19.0 |

| 80–84 years | 23.2 | 28.0 | 27.0 | 30.4 |

| 85–89 years | 18.7 | 23.8 | 25.8 | 27.3 |

| ≥90 years | 10.2 | 10.6 | 12.8 | 11.4 |

| IMD quintile* (%) | ||||

| First (least deprived) | 24.3 | 25.1 | 24.0 | 20.6 |

| Second | 25.8 | 25.4 | 22.0 | 20.4 |

| Third | 18.7 | 19.8 | 19.4 | 20.9 |

| Fourth | 19.4 | 18.0 | 19.8 | 20.6 |

| Fifth (most deprived) | 11.8 | 11.7 | 14.8 | 17.5 |

| Dementia medication† (%) | 37.3 | 32.9 | 28.1 | 23.8 |

*Only 2959 observations due to missing data.

†Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors or memantine.

IMD, Index of Multiple Deprivation.

Median number of comorbidities was 3 (IQR 2–5) and 91.8% of the people included in the study were classified as comorbid (dementia plus at least one other chronic condition). The 10 most frequent comorbidities included 6 cardiovascular-related conditions, plus chronic pain (33.5%), depression (23.5%), hearing loss (22.3%) and constipation (14.2%; table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of comorbidities

| Comorbidity | Number | Per cent | Comorbidity | Number | Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 2667 | 53.4 | Cancer within past 5 years | 251 | 5.0 |

| Painful condition | 1673 | 33.5 | Peripheral vascular disease | 203 | 4.1 |

| Depression | 1176 | 23.5 | Psoriasis or eczema | 194 | 3.9 |

| Hearing loss | 1114 | 22.3 | Migraine | 192 | 3.8 |

| Coronary heart disease | 1079 | 21.6 | Parkinson disease | 147 | 2.9 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1042 | 20.8 | Alcohol problems | 138 | 2.8 |

| Stroke | 859 | 17.2 | Inflammatory arthritis† | 105 | 2.1 |

| Constipation | 711 | 14.2 | Epilepsy | 94 | 1.9 |

| Diabetes | 701 | 14.0 | Chronic sinusitis | 69 | 1.4 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 672 | 13.4 | Bronchiectasis | 49 | <1 |

| Diverticular disease | 457 | 9.1 | Schizophrenia/psychosis | 45 | <1 |

| Prostate disorders | 443 | 25.3* | Anorexia and bulimia | 39 | <1 |

| Thyroid disorders | 429 | 8.6 | Irritable bowel syndrome | 36 | <1 |

| Asthma | 415 | 8.3 | Chronic liver disease | 30 | <1 |

| COPD | 344 | 6.9 | Substance misuse | 25 | <1 |

| Heart failure | 317 | 6.3 | Multiple sclerosis | 12 | <1 |

| Blindness and low vision | 251 | 5.0 | Learning disability | 12 | <1% |

*Percentage of male participants.

†Including other connective tissue disease.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

During the follow-up period, participants had a median of 46 primary care consultations (IQR 23–79), 2 hospitalisations (IQR 1–3) and 162 prescriptions (IQR 65–344). Numbers of consultations, hospitalisations and prescriptions by age, gender and comorbidity count are shown in table 3. There was strong evidence (p<0.001) that after adjusting for age and gender, those with very high (≥6) numbers of comorbidities had a significantly higher primary care consultation rate (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.36), hospital admission rate (RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.44 to 1.83) and prescription rate (RR 1.68, 95% CI 1.57 to 1.81) when compared with the reference group of participants with two or three comorbidities (table 3). Further adjustment for dementia medication and socioeconomic deprivation did not produce clinically relevant changes in the estimates.

Table 3.

Association between number of comorbidities and primary care consultations, hospitalisations, and medications prescribed

| Primary care consultations |

Hospitalisations* |

Medications |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Rate ratio (95% CI) | p Value | Mean (SD) | Rate ratio (95% CI) | p Value | Mean (SD) | Rate ratio (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Number of comorbidities | |||||||||

| Low, 0 or 1 | 47.6 (35.2) | 0.81 (0.78 to 0.85) | <0.001 | 2.0 (2.0) | 0.88 (0.78 to 0.99) | 0.031 | 152 (205) | 0.55 (0.52 to 0.59) | <0.001 |

| Moderate, 2 or 3 | 55.2 (41.8) | Ref | – | 2.2 (2.3) | Ref | – | 254 (307) | Ref | – |

| High, 4 or 5 | 59.6 (46.0) | 1.13 (1.09 to 1.17) | <0.001 | 2.6 (2.6) | 1.19 (1.07 to 1.32) | 0.001 | 320 (376) | 1.34 (1.27 to 1.43) | <0.001 |

| Very high, ≥6 | 63.8 (49.6) | 1.31 (1.25 to 1.36) | <0.001 | 3.4 (6.8) | 1.62 (1.44 to 1.83) | <0.001 | 365 (421) | 1.68 (1.57 to 1.81) | <0.001 |

| Female | 55.3 (42.8) | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.99) | 0.004 | 2.3 (3.7) | 0.84 (0.77 to 0.92) | <0.001 | 279 (351) | 1.16 (1.1,-1.22) | <0.001 |

| Age group | |||||||||

| <75 years | 69.2 (46.6) | Ref | – | 2.4 (2.8) | Ref | – | 295 (372) | Ref | – |

| 75–79 years | 61.3 (45.2) | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.07) | 0.27 | 2.9 (6.2) | 1.32 (1.15 to 1.50) | <0.001 | 287 (344) | 1.04 (0.96 to 1.12) | 0.318 |

| 80–84 years | 57.7 (44.1) | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.05) | 0.563 | 2.4 (2.5) | 1.28 (1.13 to 1.46) | <0.001 | 296 (368) | 1.1 (1.03 to 1.18) | 0.007 |

| 85–89 years | 47.9 (38.5) | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.07) | 0.219 | 2.3 (2.2) | 1.55 (1.36 to 1.76) | <0.001 | 242 (308) | 1.04 (0.97 to 1.12) | 0.293 |

| ≥90 years | 40.8 (34.6) | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.1) | 0.109 | 2.1 (1.9) | 1.66 (1.41 to 1.95) | <0.001 | 188 (239) | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.15) | 0.291 |

Rate ratios derived from negative binomial regression model, adjusted for age and gender. Mean values represent figures over 3 years.

*In total,2853 participants included due to missing linked data.

The association of specific frequent comorbidities and service usage is shown in table 4. Positive associations were observed between most individual comorbidities and service usage, with the strongest association observed for medication prescription. In general, effect estimates were modest and no one particular comorbidity appeared to dominate in terms of the association with the three health service usage outcomes, although there was a tendency for medication use to be slightly higher, on average, with chronic pain (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.44 to 1.59), depression (RR 1.40, 95% CI 1.32 to 1.47) and diabetes (RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.30 to 1.49).

Table 4.

Association between the type of comorbidities primary care consultations, hospitalisations and medications prescribed

| Primary care consultations |

Hospitalisations* |

Medications |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate ratio | 95% CI | p Value | Rate ratio | 95% CI | p Value | Rate ratio | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Hypertension | 1.03 | 1.00 to 1.06 | 0.021 | 0.96 | 0.88 to 1.04 | 0.286 | 1.29 | 1.23 to 1.35 | <0.001 |

| Painful disease | 1.14 | 1.10 to 1.17 | <0.001 | 1.2 | 1.09 to 1.31 | <0.001 | 1.51 | 1.44 to 1.59 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1.11 | 1.07 to 1.14 | <0.001 | 1.05 | 0.95 to 1.16 | 0.332 | 1.40 | 1.32 to 1.47 | <0.001 |

| Hearing loss | 1.01 | 0.98 to 1.04 | 0.527 | 1.02 | 0.93 to 1.13 | 0.668 | 0.98 | 0.93 to 1.04 | 0.587 |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.07 | 1.03 to 1.11 | <0.001 | 1.11 | 1.00 to 1.23 | 0.043 | 1.29 | 1.22 to 1.37 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 1.04 | 1.00 to 1.08 | 0.035 | 1.24 | 1.11 to 1.38 | <0.001 | 1.17 | 1.10 to 1.24 | <0.001 |

| Constipation | 1.09 | 1.04 to 1.13 | <0.001 | 1.23 | 1.09 to 1.39 | 0.001 | 1.04 | 0.97 to 1.12 | 0.232 |

| Diabetes | 1.18 | 1.13 to 1.22 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 1.05 to 1.33 | 0.005 | 1.39 | 1.30 to 1.49 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.17 | 1.13 to 1.22 | <0.001 | 1.26 | 1.12 to 1.42 | <0.001 | 1.20 | 1.13 to 1.29 | <0.001 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 1.07 | 1.03 to 1.11 | <0.001 | 1.1 | 0.98 to 1.22 | 0.098 | 1.03 | 1.10 to 1.24 | <0.001 |

All models adjusted for age, gender, comorbidities included in this table and the total number of comorbidities not included in this table (those with a prevalence below 10%). Further adjustment for dementia medication and deprivation produce only small changes in the estimate, suggesting that these covariates did not confound the association presented in this table.

*In total,2853 participants included due to missing linked data.

During the follow-up period 1850 (37.0%) participants died. Overall death rate was 12.7 per 100 person-years. After controlling for age and gender, there was strong evidence (p<0.001) that those with high (4–5) or very high (≥6) numbers of conditions had higher risk of death (HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.32; 1.56, 1.37 to 1.78, respectively) compared with the reference group (figure 2). Again, further adjustment for dementia medication and deprivation did not affect these estimates.

Figure 2.

Survival probabilities plotted over time for each comorbidity group.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify the association between the number of comorbidities and health service usage in people recently diagnosed with dementia in the UK. Those with the highest number of comorbidities (≥6) had a 31% higher primary care consultation rate, 68% higher prescription rate and 62% higher hospitalisation rate, compared with those in the largest group of participants with two or three comorbidities. These differences in service usage rates have significant implications in terms of health service funding, particularly given the increasing prevalence of dementia, which is the second leading cause of mortality in the UK, accounting for 10.3% of deaths in 2014.22 For example, in females aged 80–85 years, those with at least six additional comorbidities had, on average, 18.8 more primary consultations, 134.9 more prescriptions and 2.1 more hospitalisations during a 3-year period than those with two or three additional comorbidities. Based on average costs in 2013 for a GP consultation (£45),23 non-elective inpatient stay (£1489)24 and net ingredient cost per prescription item (£8.37),25 this excess service usage would have represented an estimated cost difference of £5100 per person over 3 years.

The association between the number of comorbidities and health service usage might be expected to depend on the presence of specific comorbidities. Nevertheless, when the effect of the most frequent comorbidities was assessed, there was no clear evidence for one particular condition predominating in terms of driving health service usage. This may reflect a lack of clinical detail about the separate conditions, such as disease severity, but nevertheless suggests that assessing the presence of specific comorbidities using routine data provides little additional insight into the overall burden on health services beyond that gained from simply looking at number of conditions.

Although primary care is already well placed to support patients with multimorbidity in general, there is still a need to explore whether there are options to improve how it responds to the needs of those with dementia, in order to reduce higher levels of health service usage in these patients. It is also worth considering whether service use in these patients could be determined by factors other than care needs, such as health service organisation or health-seeking behaviours. Nevertheless, the number of comorbidities was also significantly associated with the risk of death, which suggests that the most comorbid individuals still have fundamentally increased healthcare needs that have to be met.

Comparison with other studies

Our findings are similar to those reported by Boyd and colleagues in the USA, which also reported considerable variation in service usage rates with degree of morbidity. Although the US study differs by assessing specific patterns, rather than the number of conditions,12 both suggest that comorbidity is a key factor driving this variation. Regarding the effect of specific comorbidities, the majority of our results were as clinically expected. Of particular note, the lack of association of depression with hospitalisation is at odds with some of our previous work,13 although the fact that all participants of this study had a neuropsychiatric condition (dementia) could potentially lead to an underestimate in the effect of further mental diseases. The rates of primary care contact we observed are higher to those found by other UK work,3 probably explained by differences in service use definition and average disease severity inferred from higher mortality rates.

The prevalence of comorbidity found in this study (91.7%) concurs with the 94.7% prevalence described among prevalent cases of dementia in Scotland by Barnett et al.11 Consistent with several other studies that describe multimorbidity patterns, hypertension was the most frequent comorbidity.26 The prevalence of hypertension (53.4%) was lower than that estimated for the general population aged 60–80 years in a recent English national health survey (63.7%),27 but the prevalence of painful condition (33.5%) was high in comparison to that observed in populations with heart disease, diabetes and cancer (12–32%).11

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

By using electronic health records, we were able to sample a relatively large number of incident cases of dementia, providing a good representation of the UK population and thus good external generalisability. We also examined a range of outcomes, providing us with insight into primary and secondary health service usage, including both contact with services and provision of treatment. However, it is also necessary to consider a number of important limitations. As with most studies employing primary care records, there is no standard set of codes available to identify conditions, data quality varies across practices15 and missing data are often present. Misclassification of comorbidities may or may not be associated with degree of health service contact (eg, opportunistic coding of disease during a consultation), thus increasing or decreasing, respectively, the apparent strength of the observed association. A further limitation is that hospital admission data were missing for 40.1% of cases due to a lack of governance permissions for data linkage, although we do not believe there is any reason that linkage rates are likely to be associated with hospital admission rates. Another limitation is our choice of hospital and prescribing outcome measures. Elective hospital admissions may reflect appropriate clinical care, which is not necessarily the case with unplanned admissions. However, we were not able to differentiate urgency of admission using the data available. We are also unable to tell whether admissions were potentially avoidable. Furthermore, a crude count of medications is unable to capture the appropriateness of treatment. Nevertheless, such measures have the benefit of simplicity and transparency, and still provide useful insights into overall service use. Additional outcomes which would provide more detailed insight into service use also include quality of life and quality of service provision, but unfortunately these were not readily available in our data set. A further limitation is the potential for differential loss to follow-up between exposure groups leading to selection bias. The main reason for loss to follow-up was transfer to another practice, although the reason for transfer was unknown. Importantly, those who were transferred out were older and with more comorbidities. If differences reflected individuals with poorer health being admitted to long-term nursing or residential care facilities, we might expect the true strength of the association between comorbidities and service usage to be even greater than that we observed. Our use of incident as opposed to prevalent cases may result in apparently lower rates of service use, due to patients having milder dementia, although this could be offset by a tendency for increased diagnostic recording prompted by greater contact with health services in patients with more advanced disease; the lack of data on dementia severity makes this issue hard to resolve. We have also not accounted for any potential variations in service use over time within individuals, such as increases leading up to death. Finally, our study only examines primary and secondary healthcare provision, as data were not available to allow us to quantify long-term social care needs.

Conclusions and policy implications

Our findings emphasise that comorbidity is common and associated with substantially increased service use in the dementia population. Although the nature of this association follows what is clinically expected, its quantification provides valuable evidence to support changes in the design of health and care services. There is evidence to suggest that integrated care programmes based on strong primary care services could improve the sustainability of health systems in comorbid populations.28 However, epidemiological evidence of the effect of comorbidities on people diagnosed with prevalent and high care cost diseases is scarce. Based on this study, the number of comorbidities could potentially be used to guide healthcare resource allocation. This includes ensuring the most multimorbid are targeted by dementia-management policies addressing issues such as hospital admission avoidance, long-term community medical care and medication optimisation. Comorbidity burden may also be used to inform decision-making relating to the type (eg, palliative care or normal care) and place of care for people with dementia. Therefore, the findings of this study should be used to increase awareness of comorbidity in dementia care and to encourage adaptation of services accordingly. Further work evaluating patterns of comorbidities and different dimensions of health, such as quality of life, is also needed to achieve a better understanding of the impact of comorbidity on people with dementia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carol Brayne for general guidance and advice on dementia research and Carol Wilson for help with the diagnostic code selection.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Jorge Browne @jorgebrowne

Collaborators: Professor Carol Brayne Carol Wilson.

Contributors: All authors fulfil the authorship criteria recommended by ICMJE. JB designed the methods, cleaned the data, contributed in the code selection, implemented the analysis and drafted the paper. He is the guarantor. DAE co-designed the methods, organised and contributed in the code selection, drafted and revised the paper. KMR co-designed and revised the statistical analysis. DJB managed the code selection and the database. RAP co-designed the methods, contributed in the code selection, drafted and revised the paper.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the CPRD Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (ISAC protocol number 15_106R).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data are available by emailing jabrowne@uc.cl.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Carol Brayne and Carol Wilson

References

- 1.Alzheimer's Society. Dementia UK: update. London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer Disease International. The global economic impact of dementia. London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L, Reed C, Happich M et al. Health care resource utilisation in primary care prior to and after a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: a retrospective, matched case-control study in the United Kingdom. BMC Geriatr 2014;14:76 10.1186/1471-2318-14-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fillit H, Hill JW, Futterman R. Health care utilization and costs of Alzheimer's disease: the role of co-morbid conditions, disease stage, and pharmacotherapy. Fam Med 2002;34:528–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunik ME, Snow AL, Molinari VA et al. Health care utilization in dementia patients with psychiatric comorbidity. Gerontologist 2003;43:86–91. 10.1093/geront/43.1.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scalmana S, Di Napoli A, Franco F et al. Use of health and social care services in a cohort of Italian dementia patients. Funct Neurol 2013;28:265–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bunn F, Burn AM, Goodman C et al. Comorbidity and dementia: a scoping review of the literature. BMC Med 2014;12:192 10.1186/s12916-014-0192-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melis RJ, Marengoni A, Rizzuto D et al. The influence of multimorbidity on clinical progression of dementia in a population-based cohort. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e84014 10.1371/journal.pone.0084014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon A, Dobranici L, Kåreholt I et al. Comorbidity and the rate of cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;26:1244–51. 10.1002/gps.2670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Dementia: a public health priority. London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyd CL, Weiss B, Wolff C et al. Full report: clarifying multimorbidity to improve targeting and delivery of clinical services for Medicaid populations. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc., 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Payne RA, Abel GA, Guthrie B et al. The effect of physical multimorbidity, mental health conditions and socioeconomic deprivation on unplanned admissions to hospital: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ 2013;185:E221–8. 10.1503/cmaj.121349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clinical Practice Research Datalink. 2015. http://www.cprd.com/home/

- 15.Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K et al. Data resource profile: clinical practice research datalink (CPRD). Int J Epidemiol 2015;44, 827-36. 10.1093/ije/dyv098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrett E, Thomas SL, Schoonen WM et al. Validation and validity of diagnoses in the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2010;69:4–14. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03537.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan NF, Harrison SE, Rose PW. Validity of diagnostic coding within the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:e128–36. 10.3399/bjgp10X483562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant RL, Drennan VM, Rait G et al. First diagnosis and management of incontinence in older people with and without dementia in primary care: a cohort study using the health improvement network primary care database. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001505 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan NF, Perera R, Harper S et al. Adaptation and validation of the Charlson Index for Read/OXMIS coded databases. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:1 10.1186/1471-2296-11-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scitovsky AA. “The high cost of dying”: what do the data show? Milbank Q 2005;83:825–41. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00402.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams G, Gulliford MC, Ukoumunne OC et al. Patterns of intra-cluster correlation from primary care research to inform study design and analysis. 2004;57:785–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.2015. (ONS) ONS. Deaths Registered in England and Wales (Series DR), 2014. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_422395.pdf.

- 23.Personal Social Services Research Unit. Unit costs of health and social care 2013. Canterbury, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.2013. (UK) DoH. Reference costs 2012-13. http://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-reference-costs-2012-to-2013.

- 25. Health & Social Care Information Centre. National Statistics Prescription Cost Analysis, England—2013 2014 http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB13887.

- 26.Violan C, Foguet-Boreu Q, Flores-Mateo G et al. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e102149 10.1371/journal.pone.0102149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joffres M, Falaschetti E, Gillespie C et al. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in national surveys from England, the USA and Canada, and correlation with stroke and ischaemic heart disease mortality: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003423 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colombo F, García-Goñi M, Schwierz C. Addressing multimorbidity to improve healthcare and economic sustainability. 2016;6:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012546supp_appendix1.pdf (93.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012546supp_appendix2.pdf (170.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012546supp_appendix3.pdf (46.8KB, pdf)