Abstract

Objectives

We assessed stakeholder perceptions on the use of an electronic consultation system (e-Consult) to improve the delivery of kidney care in Alberta. We aim to identify acceptability, barriers and facilitators to the use of an e-Consult system for ambulatory kidney care delivery.

Methods

This was a qualitative focus group study using a thematic analysis design. Eight focus groups were held in four locations in the province of Alberta, Canada. In total, there were 72 participants in two broad stakeholder categories: patients (including patients' relatives) and providers (including primary care physicians, nephrologists, other care providers and policymakers).

Findings

The e-Consult system was generally acceptable across all stakeholder groups. The key barriers identified were length of time required for referring physicians to complete the e-Consult due to lack of integration with current electronic medical records, and concerns that increased numbers of requests might overwhelm nephrologists and lead to a delayed response or an unsustainable system. The key facilitators identified were potential improvement of care coordination, dissemination of best practice through an educational platform, comprehensive data to make decisions without the need for face-to-face consultation, timely feedback to primary care providers, timeliness/reduced delays for patients' rapid triage and identification of cases needing urgent care and improved access to information to facilitate decision-making in patient care.

Conclusions

Stakeholder perceptions regarding the e-Consult system were favourable, and the key barriers and facilitators identified will be considered in design and implementation of an acceptable and sustainable electronic consultation system for kidney care delivery.

Keywords: electronic consultation, kidney care, CKD, rural/remote communities, quality of care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The use of electronic consultation systems to facilitate interactions between specialists and primary care practitioners has not been widely adopted in Canada for kidney care delivery.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that explored the feasibility of e-Consult for ambulatory kidney care—the barriers to and facilitators of uptake of the system among patients and providers, prior to its implementation.

We leveraged a robust methodological design, reported on stakeholder perceptions about potential barriers to and facilitators for e-Consult implementation.

These results have direct implications for a health system redesign and inform the development and implementation of this electronic system aimed to improve access to specialist kidney care.

The key limitations were that focus group studies, though important source of information, are dependent on the knowledge, expertise and perceptions of the participants.

Introduction

Specialist kidney care is critical for diagnosis and management of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), particularly those with advanced CKD, and over the last decade there has been a steady increase in the number of referrals to nephrologists.1–7 This issue is compounded by the large rural geography of Canada, with resultant disparities in the distribution of healthcare resources, health workforce and access to care.8 9 Thus, there is a need for an alternate CKD care delivery model that can facilitate efficient, effective, cost-saving, convenient and timely care for patients with CKD, particularly those living in rural/remote locations.

The use of electronic consultation systems—secure and confidential electronic system of using patients' health information to facilitate a meaningful interaction between a specialist and a primary care provider (PCP) (herein referred to as e-Consult)—and other telehealth systems to facilitate access to specialist care is entering the clinical arena in many countries.10–17 Nevertheless, e-Consult systems have not been widely adopted in Canada.11 13 18–21 It is crucial to establish the feasibility, acceptability and the optimal format for such a system prior to its implementation.22

We aim to develop an e-Consult system for CKD for PCPs in Alberta. The purpose of this study was to explore the barriers to and facilitators of uptake of the system among patients and providers, prior to its implementation.

Methods

The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) were used to structure and report the study findings.23

Setting

The primary responsibility for provision of healthcare in Canada is by the various provinces and territories. The funding for healthcare is single payer at each level of delivery and provided by each province or territory with some contributions by the federal government. The system encompasses a public basic insurance coverage combined with private insurance beyond the basic coverage. Alberta is one of the 10 provinces in the country. Patients do not pay for ambulatory care delivered by a PCP or specialist in Alberta, as this is covered by the public coverage that provided fee codes for referring and consulting physicians.

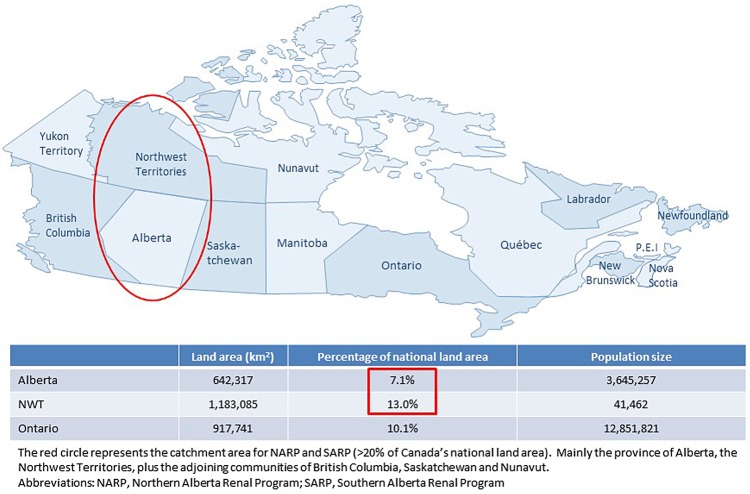

The study was conducted across the province of Alberta, supported by the Northern and Southern Alberta Renal Programs (NARP/SARP). These are large renal programmes in Canada, providing care to ∼4 million people residing in western and northern Canada. The two programmes have a catchment area characterised by a vast geography (Alberta and Northwest Territories (NWT), as well as adjoining parts of British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Nunavut); this area constitutes >20% of the Canada national land area and includes remote locations with low population density (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of Canada showing the Alberta Kidney Care Programs (NARP & SARP): Vast geographical catchment area and sparse population across remote communities and regions. NARP/SARP, Northern and Southern Alberta Renal Programs.

Alberta e-Consult initiative

The Alberta e-Consult provides a secure, reliable and efficient platform for the interactions of PCPs and nephrologists to deliver ambulatory kidney care. This tool is hosted on the provincial Netcare system, a secure and confidential electronic system of patients' health information in Alberta. The e-Consult model involves direct asynchronous communication between referring physicians and nephrologists via a Netcare portal to coordinate patient management and limit face-to-face visits between patients and nephrologists to situations where such visits are truly required.

Design and population

This study was part of a larger integrated, sequential and mixed methods study24–27 conducted in three phases.28 29 The focus of this report is the preimplementation phase in which the perceptions, readiness and key barriers and facilitators to the uptake of the e-Consult system were explored to identify key issues fundamental to its implementation and widespread application. A qualitative focus group study with purposive sampling and thematic analysis was conducted in this phase of the study. The design was chosen since it is the most appropriate for studies exploring feasibility of programmes and stakeholder views/opinions to implementation, when little is known about the topic.

Sampling in this particular study was purposive; statistical power and generalisation were not the aim.25–27 29 We purposively selected study participants to ensure that our survey captured the views of the stakeholders, including PCPs, nephrologists and policymakers involved directly with the organisation of CKD care and patients with CKD and their relatives

People in the identified groups of the study population were invited to participate in a focus group session via email and/or mailed letters of invitation. Sessions with patient groups were conducted separately from provider groups. No financial incentives were offered for participation.

Data collection

Data were collected in eight focus groups, four with patient groups and four with provider groups. They were conducted in four locations (clinics) across urban and rural Alberta by the lead investigator (AKB), who is male and an academic physician/nephrologist (MD, PhD). An experienced facilitator familiar with the study and its aims facilitated the focus groups, asking pertinent questions and prompting questions when necessary.30 An observer was also present to witness proceedings, manage equipment and examine issues of group dynamics. Each focus group lasted for ∼2 hours, was audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. A semistructured interview guide was used (eAppendix 1, eFigure 1).31–33 In the development of the patient-specific questions, we used the Picker Institute Model, which is based on eight dimensions of patient perspectives to care provision.34 35 The open-ended nature of the questions provided opportunities for extensive exploration of the issues. No prior relationship was established with the study participants. Focus group participants were informed at the start of each focus group session the key objectives of the study (reasons for the focus group) and a declaration of no conflict of interest from the investigator and other members of the study team.

bmjopen-2016-014784supp_appendix.pdf (305.9KB, pdf)

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted using categories (eAppendix 2) established a priori based on the research questions relating to acceptability, barriers and facilitators to implementing an electronic consultation service. Two analysts, who were not part of data collection, reviewed and coded the focus group transcripts, using NVivo 10 qualitative data analysis software. Transcript data was divided into small meaningful units (ie, sentence, phrase, paragraph related to topic) and a descriptor was attached to each of the units. Contrasting perspectives that did not fit the themes were also identified. As the analysts immersed themselves in the data, themes crystallised and saturation of categories was evident.36 The transcripts were not returned to the participants for comments. Analysis of the patient and provider focus groups was conducted separately. Themes for the two groups (patients and providers) were then compared.

Results

Participants

There was a total of 72 participants (n=36 in patient and provider groups) (table 1). Table 2 provides a summary of the demographics of the focus group participants. All invited providers and patients participated.

Table 1.

Focus group geographical distribution and modality of facilitation

| Focus group | Location | Participant group | # of participants | Date conducted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | Calgary* | Patients/relatives | 7 | 9 June 2015 |

| #2 | Calgary* | Providers/policymakers | 8 | 9 June 2015 |

| #3 | Edmonton* | Patients/relatives | 8 | 19 February 2015 |

| #4 | Edmonton* | Providers/policymakers | 15 | 19 February 2015 |

| #5 | Peace River† | Patients/relatives | 10 | 25 February 2015 |

| #6 | Peace River* | Providers/policymakers | 6 | 24 February 2015 |

| #7 | Brooks* | Patients/relatives | 11 | 10 June 2015 |

| #8 | Brooks† | Providers/policymakers | 7 | 10 June 2015 |

*In-person.

†In-person/virtual.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of focus group participants

| Provider focus groups |

Patient focus groups |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=36) (%) | (n=36) (%) | ||

| Gender | Gender | ||

| Males | 21 (61.1) | Males | 17 (47.2) |

| Females | 15 (38.9) | Females | 19 (52.8) |

| Time in practice (years)* | Location of residence: | ||

| <5 | 1 (3.1) | Rural | 21 (58.3) |

| 5–10 | 2 (6.3) | Urban | 15 (41.7) |

| 10–20 | 11 (34.4) | Designation: | |

| >20 | 18 (56.2) | Patient | 31 (86.1) |

| Profession grouping: | Family | 4 (11.1) | |

| Nephrologists | 10 (27.8) | Other‡ | 1 (2.8) |

| General practitioners | 15 (41.7) | ||

| Others† | 11 (30.6) | ||

| Practice location: | |||

| Rural | 13 (36.1) | ||

| Urban | 23 (63.9) | ||

*Years since medical school graduation for physicians only (n=32).

†Includes non-nephrology specialists and nurse practitioners.

‡Friend of patient.

Key findings

The themes of acceptability, barriers and facilitators as found in the patient and provider datasets, with some areas of overlap, are described below in an integrated presentation and separated for ease of comparison in table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of key findings

| Provider focus groups | Patient focus groups |

|---|---|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Incentives | |

|

NA |

|

|

| Ease of use | |

|

NA |

| Ease of communication between referring physicians and nephrologists: | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

CME, continuing medical education; EMR, electronic medical records; NA, not applicable, PCPs, Primary care providers.

Acceptability

Few concerns about the concept of e-Consult were raised in the focus groups. Providers and patients described the potential benefits to patients of e-Consult in terms of decreased wait times and more appropriate and effective referrals—only patients the nephrologist identified as requiring a nephrology consult would be seen in person, whereas, others could be safely managed by their referring physician in the community. Participants perceived this would eliminate inappropriate referrals and make better use of resources such as appointment times. This was especially appreciated by participants outside of urban centres, who noted an opportunity to decrease patient burden by reducing unnecessary travel for inappropriate visits.

Well we'd get information faster so that our doctor could know, would know what to do.

That would be a benefit, yeah.

Yeah, without us having to travel.

Lots of times you could be treated without going anywhere too. (Patient)

Patients and providers agreed that through e-Consult, nephrology referrals would be more effective as appropriate tests would be ordered and results communicated to the nephrologist prior to the scheduled visit (or in place of the visit). Similarly, the outcomes of the nephrology consult would be more accurately reported back to the referring physician through e-Consult, thus enabling a higher quality of care. An additional benefit of the e-Consult system commonly noted by providers was increased confidence in physician decision-making about kidney care. Some attributed this confidence to the current best practices content of the e-Consult system. Others proposed that increased confidence would result because decisions about kidney care would be reviewed by a nephrologist.

If you enter this in the system and you get it clear that you know why you do not have to refer; you have that on file, as even a legal statement, saying, “Hey I did an e-referral. It was generated half-electronically and briefly reviewed by a nephrologist.” And at least I feel comfortable. I can tell my patient that we have a couple of decision rules when he needs to be referred. It's also to give confidence that you're okay just to follow people. (Provider)

Barriers

Although participants were in favour of the e-Consult system in principle, some practical concerns regarding its implementation were identified: potential decreased access to care for patients by increasing wait times at other points in the care pathway, lack of integration with current electronic medical record (EMRs) systems in physician offices and the length of time required for physicians to complete the e-Consult.

Interestingly, patients and providers speculated that the new system might inadvertently slow the course of kidney care.

The only part that I'm concerned with is the overload of your local doctors, which will slow down the information back to your patient….. (Patient)

Providers voiced concerns that the potential increase in nephrology referrals as a result of having the e-Consult system might overwhelm the nephrologists, leading to delay in response or creation of a system that was not sustainable.

F3: But is there a plan for physician sustainability? Because even though it's faster to answer a question on email or over electronic, you could be having 75 of those as opposed to seeing four patients. (Provider)

Another area of concern for patients and providers was the capacity of information technology systems to effectively house the e-Consult system. A few patients speculated that rural PCPs may lack the required internet resources. Most providers' comments were centred on the lack of integration of the system and any outcomes of the consultation (eg, laboratory tests, results) with their EMRs. The high prevalence of these comments made ‘lack of integration with EMR’ one of the strongest themes in the provider data set.

My only barrier would be if I have two separate systems that I have to go log on and in and on and in to see what's going on…But I don't want to have two systems that now I have to check this, now I have to check this. (Provider)

Apprehension about the lack of integration across EMRs was closely interrelated with the amount of time to complete the e-Consult.

Well I think that's the biggest barrier for primary care docs that we see for e-Consult is exactly that, it's very labour intensive. When we made great efforts to populate our own EMR with relevant information and now we have to reinvent the wheel again to put it into the e-Consult system so I think that if that could be fixed it would be awesome. (Provider)

The length of time to complete the e-Consult was problematic primarily because of the fee-for-service Canadian context. Some providers assumed (inaccurately) that PCPs would not be compensated for their time spent completing the e-Consult.

Facilitators

Focus group discussion about what would facilitate implementation of the e-Consult system was categorised into three main areas: incentives, ease of use and enabling communication between referring physicians and nephrologists.

When concerns were raised about completion of the e-Consult, providers suggested that incentives would encourage acceptance and use of the e-Consult system. When providers in the focus groups understood that financial compensation would be available and allow them to bill for form completion, it was consistently received with enthusiasm.

But is there a plan or is there going to be some kind of a fee schedule for this service? There will be good buy-in for guys who are working fee-for-service. It's going to take a significant chunk of time. (Provider)

Another incentive, suggested less frequently, was awarding Continuing Medical Education (CME) credits for the best practices content of the e-Consult system.

I wonder if you want to again attach a carrot, if you can give CME credit. …Because then you might not get paid for…navigating that CKD pathway with the patient but if you can say, “Well no, I went through it and it took me a half an hour and that's my CME credit.” (Provider)

One of the strongest themes within the provider data set was ‘ease of use’. This was related to discussion about the importance of the e-Consult system being easy to use, accompanied by suggestions such as make the process quick, minimise the number of logins and integrate it as much as possible with existing systems such as Netcare and EMRs.

I'm a primary care physician too. I worked in a rural area before now. Now three things: One is that you want something so easy to use…something that click-click-click. (Provider)

The concept of the e-Consult system being easy to use was often equated with it not taking too much time and not duplicating work completed in other work processes.

As GPs, we've worked hard to get this EMR system going for us but now you've got to reinvent the wheel, I've got to pull all the data, re-enter it…there's no access; I have to go out and handwrite it and type it in. That's very time consuming, yeah. (Provider)

Ensuring ease of use was identified as essential to achieving the benefits apparent in using the system: for providers, reducing duplication of work, improving quality and for patients, increasing access and reducing wait times.

Some providers similarly stated that knowing the nephrologist and engaging in two-way communication to comanage patients with CKD could increase their ability and confidence in meeting best practice. This was corroborated by nephrologists participating in the focus groups:

We can always work around that where you have the certain doc that you're used to referring to. You still want to keep that relationship going in certain cases that are not too clear-cut. Sometimes maybe you're not going to be able to write but you can just pick your phone up and talk to the doc. (Provider)

Discussion

Using focus groups, we explored stakeholder perceptions about potential barriers to and facilitators for a new electronic consultation strategy, focusing on elements that are most important for the design of a feasible, acceptable and implementable e-Consult system.37–39 These results will be used to inform the development and implementation of this electronic system aimed to improve access to specialist kidney care.

Previous data have documented evidence of benefits of using telehealth to facilitate patient care in nephrology.11 13 40–43 However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to identify important factors that could hinder or facilitate the introduction of electronic consultation in kidney care for patients with CKD. Through our focus group study with provider and patient participants, we have been able to establish that the e-Consult system is generally acceptable given its potential to reduce or remove travel time, improve information sharing between PCPs and nephrologists and ensure appropriate tests are performed and communicated between PCPs and nephrologists. We also identified that providers and patients are generally in agreement regarding the usefulness of such a system and the impact it could have in improving patient care and boosting confidence of non-nephrology physicians in kidney care. Chen et al37 described the advantages of an e-Consult system including: reduction in the demand for clinic visits for some patients due to comanaged care, which results in shorter waiting times for patients who need a visit and formalisation of the ‘curbside consult’ in a manner that addresses certain limitations (eg, incomplete data and lack of documentation of the interaction), but identifies cases that require formal consultation and avoidance of the contentious issue of whether a particular referral is appropriate.

Our ability to integrate the e-Consult system with an existing province-wide and secured EMR (Alberta Netcare), with automated interface for consultations and patients' data pull, facilitates potential for wider practice adoption and implementation. This has potential for impact, with strong policy implications, as it would allow us to partner with providers and policymakers in the provincial renal programmes and to improve kidney care delivery by implementing the new model for PCP–nephrologist interactions. The study findings lead naturally into more indepth studies to generate evidence on the relevance and feasibility of a model of electronic consultation to improve the care of patients with CKD, as a potential educational platform for PCPs, and to change the way kidney care is delivered in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, accessibility and timeliness. This work has potential to favourably influence referral patterns, access to care, care quality, patient outcomes and healthcare costs for people with CKD, which is a common and expensive condition. Once benefit is demonstrated for patients with CKD, our findings will be applicable to other chronic diseases.

There are some limitations to this study. Focus group studies are an important source of information but are dependent on the knowledge, expertise and perceptions of the participants. We carefully selected participants by the most important variables to mitigate some of these limitations. Varying degrees of expertise and knowledge may have contributed to reported perceptions; for example, technologically savvy participants might have viewed e-Consult more favourably. Further, one of the key criticisms of qualitative research is limited generalisability of the results to a larger population. We mitigated this by ensuring a minimum number of participants for each stakeholder group, which were all analysed and a theoretical saturation was obtained.30 36 However, an interim analysis in between focus groups was not conducted.

This work, using a robust methodological design, reported on stakeholder perceptions about potential barriers to and facilitators for e-Consult implementation, focusing on elements that are most important for the design of a feasible, acceptable and implementable intervention. The participants in this study had a favourable view of the e-Consult system as an alternate ambulatory kidney care delivery model, and this support suggests a high likelihood of success when implemented. These findings would allow us to partner with renal programmes across the province to potentially improve ambulatory kidney care delivery, and subsequently implementing and evaluating the effectiveness of the system on patients' outcomes and cost savings, which is the subject for future, indepth studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sue Szigety, Annabelle Wong and Anita Kozinski for their support with the organisation and conduct of the focus groups and project management. The significant contributions of the care providers and their patients who attended the sessions are greatly acknowledged.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Stephanie Thompson @StephanieTh11

Contributors: Authorship followed International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) guidelines. AKB and MT were responsible for the inception and design of the project and prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. AEM, LPG, JG, ST, EK, CL, BM, KJ, SK and BH provided methodological input, and participated in the acquisition, analysis, interpretation and reporting of data. MAO and IGO participated in the acquisition, analysis, interpretation and reporting of data. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by a grant from the MSI Foundation, Edmonton, Alberta and Alberta Innovates Health Solutions–Collaborative Research and Innovation Opportunities (CRIO). Authors have no other disclosures to make.

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in the design, collection, analysis, interpretation, writing or submission of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Health Research Ethics Boards at the University of Alberta and the University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hemmelgarn BR, Zhang J, Manns BJ et al. Nephrology visits and health care resource use before and after reporting estimated glomerular filtration rate. JAMA 2010;303:1151–8. 10.1001/jama.2010.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James MT, Hemmelgarn BR, Tonelli M. Early recognition and prevention of chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2010;375:1296–309. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62004-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levey AS, Atkins R, Coresh J et al. Chronic kidney disease as a global public health problem: approaches and initiatives—a position statement from Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes. Kidney Int 2007;72:247–59. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levey AS, Coresh J. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2012;379:165–80. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60178-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:137–47. 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perico N, Remuzzi G. Chronic kidney disease: a research and public health priority. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27(Suppl 3):iii19–26. 10.1093/ndt/gfs284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rucker D, Hemmelgarn BR, Lin M et al. Quality of care and mortality are worse in chronic kidney disease patients living in remote areas. Kidney Int 2011;79:210–17. 10.1038/ki.2010.376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bello AK, Hemmelgarn B, Lin M et al. Impact of remote location on quality care delivery and relationships to adverse health outcomes in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:3849–55. 10.1093/ndt/gfs267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liddy C, Rowan MS, Afkham A et al. Building access to specialist care through e-consultation. Open Med 2013;7:e1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schachter ME, Romann A, Djurdev O et al. The British Columbia Nephrologists’ Access Study (BCNAS)—a prospective, health services interventional study to develop waiting time benchmarks and reduce wait times for out-patient nephrology consultations. BMC Nephrol 2013;14:182 10.1186/1471-2369-14-182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scherpbier-de Haan ND, van Gelder VA, Van Weel C et al. Initial implementation of a web-based consultation process for patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:151–6. 10.1370/afm.1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Speedie SM, Ferguson AS, Sanders J et al. Telehealth: the promise of new care delivery models. Telemed J E Health 2008;14:964–7. 10.1089/tmj.2008.0114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoves J, Connolly J, Cheung CK et al. Electronic consultation as an alternative to hospital referral for patients with chronic kidney disease: a novel application for networked electronic health records to improve the accessibility and efficiency of healthcare. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:e54 10.1136/qshc.2009.038984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee BJ, Forbes K. The role of specialists in managing the health of populations with chronic illness: the example of chronic kidney disease. BMJ 2009;339:b2395 10.1136/bmj.b2395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haldis TA, Blankenship JC. Telephone reporting in the consultant-generalist relationship. J Eval Clin Pract 2002;8:31–5. 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2002.00313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan E, Cusack C, Hook J et al. The value of provider-to-provider telehealth. Telemed J E Health 2008;14:446–53. 10.1089/tmj.2008.0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox CH, Vest BM, Kahn LS et al. Improving evidence-based primary care for chronic kidney disease: study protocol for a cluster randomized control trial for translating evidence into practice (TRANSLATE CKD). Implementation Science 2013;8:88 10.1186/1748-5908-8-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlfjord S, Andersson A, Bendtsen P et al. Applying the RE-AIM framework to evaluate two implementation strategies used to introduce a tool for lifestyle intervention in Swedish primary health care. Health Promot Int 2012;27:167–76. 10.1093/heapro/dar016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glasgow RE, Askew S, Purcell P et al. Use of RE-AIM to address health inequities: application in a low-income community health center based weight loss and hypertension self-management program. Translational Behavioral Medicine 2013;3:200–10. 10.1007/s13142-013-0201-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glasgow RE, Dickinson P, Fisher L et al. Use of RE-AIM to develop a multi-media facilitation tool for the patient-centered medical home. Implementation Science 2011;6:118 10.1186/1748-5908-6-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glasgow RE, Phillips SM, Sanchez MA. Implementation science approaches for integrating eHealth research into practice and policy. Int J Med Inf 2014;83:e1–11. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Straus SG, Chen AH, Yee H Jr et al. Implementation of an electronic referral system for outpatient specialty care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2011;2011:1337–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee C, Rowlands IJ. When mixed methods produce mixed results: integrating disparate findings about miscarriage and women's wellbeing. Br J Health Psychol 2015;20: 36–44. 10.1111/bjhp.12121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voncken-Brewster V, Tange H, Moser A et al. Integrating a tailored e-health self-management application for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients into primary care: a pilot study. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:4 10.1186/1471-2296-15-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee S, Smith CA. Criteria for quantitative and qualitative data integration: mixed-methods research methodology. Comput In form Nurs 2012;30:251–6. 10.1097/NXN.0b013e31824b1f96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ 2010;341:c4587 10.1136/bmj.c4587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan DL. Practical strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative methods: applications to health research. Qual Health Res 1998;8:362–76. 10.1177/104973239800800307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dennis ML, Perl HI, Huebner RB et al. Twenty-five strategies for improving the design, implementation and analysis of health services research related to alcohol and other drug abuse treatment. Addiction 2000;95(Suppl 3):S281–308. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.95.11s3.2.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitzinger J. The Methodology of focus groups—the importance of interaction between research participants. Sociology of Health Illness 1994;16:103–21. 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11347023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poses RM, Levitt NJ. Qualitative research in health care. Antirealism is an excuse for sloppy work. BMJ 2000;320:1729–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 2000;320:50–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liddy C, Maranger J, Afkham A et al. Ten steps to establishing an e-consultation service to improve access to specialist care. Telemed J E Health 2013;19:982–90. 10.1089/tmj.2013.0056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eye on patients: excerpts from a report on patients’ concerns and experiences about the health care system. American Hospital Association and the Picker Institute. J Health Care Finance 1997;23:2–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrissey J. Ready for a comeback. Picker Institute to move beyond patient surveys. Mod Healthc 2003;33:18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borkan J. Immersion/crystallization. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, eds. Doing qualitative research. 2nd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen AH, Murphy EJ, Yee HF Jr.. eReferral–a new model for integrated care. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2450–3. 10.1056/NEJMp1215594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rashid M, Abeysundra L, Mohd-Isa A et al. Two years and 196 million pounds later: where is Choose and Book? Inform Prim Care 2007;15:111–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heimly V. Electronic referrals in healthcare: a review. Stud Health Technol Inform 2009;150:327–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.AlAzab R, Khader Y. Telenephrology application in rural and remote areas of Jordan: benefits and impact on quality of life. Rural Remote Health 2016;16:3646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishani A, Christopher J, Palmer D et al. Telehealth by an interprofessional team in patients with ckd: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis 2016;68:41–9. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gómez-Martino JR, Suárez MA, Gallego SD et al. [Telemedicine applied to Nephrology. Another form of consultation]. Nefrologia 2008;28:407–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braverman J, Samsonov DV. A study of online consultations for paediatric renal patients in Russia. J Telemed Telecare 2011;17:99–104. 10.1258/jtt.2010.100410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014784supp_appendix.pdf (305.9KB, pdf)