Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the extent of delay in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE) in primary care, and to identify determinants that are associated with such diagnostic delay.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Setting

6 primary care practices across the Netherlands.

Participants

Data from patients with an objectively confirmed diagnosis of PE (International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) code K93) up to June 2015 were extracted from the electronic medical records. For all these PE events, we reviewed all consultations with their general practitioner (GP) and scored any signs and symptoms that could be attributed to PE in the 3 months prior to the event. Also, we documented actual comorbidity and the diagnosis considered initially.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Delay was defined as a time gap of >7 days between the first potentially PE-related contact with the GP and the final PE diagnosis. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent determinants for delay.

Results

In total, 180 incident PE cases were identified, of whom 128 patients had 1 or more potential PE-related contact with their GP within the 3 months prior to the diagnosis. Based on our definition, in 33 of these patients (26%), diagnostic delay was observed. Older age (age >75 years; OR 5.1 (95% CI 1.8 to 14.1)) and the absence of chest symptoms (ie, chest pain or pain on inspiration; OR 5.4 (95% CI 1.9 to 15.2)) were independent determinants for diagnostic delay. A respiratory tract infection prior to the PE diagnosis was reported in 13% of cases without delay, and in 33% of patients with delay (p=0.008).

Conclusions

Diagnostic delay of more than 7 days in the diagnosis of PE is common in primary care, especially in the elderly, and if chest symptoms, like pain on inspiration, are absent.

Keywords: pulmonary embolism, diagnostic delay, PRIMARY CARE, venous thromboembolism

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study identified objectively confirmed cases of pulmonary embolism (PE) based on International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) coding in Dutch primary care practices. In all PE cases, individual patient files were reviewed by at least two researchers independently to identify potential diagnostic delay.

Using the electronic individual patient files, we were able to assess information on general practitioner (GP) consultations, as well as correspondence between GPs, hospital specialists and results from laboratory and imaging tests performed.

Since we had to rely on correct ICPC coding in all primary care practices, there is a chance of incomplete selection of all PE cases. However, we believe that this miscoding will be present in only a minor fraction of all PE cases given the relevance of correct coding.

Furthermore, our study is limited by not including information on determinants like oxygen saturation, heart rate and D-dimer levels due to incomplete recordings.

Introduction

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is listed among the diagnoses most frequently missed, or delayed, in clinical practice.1 In fact, a substantial part of the estimated 500 000 deaths per year attributed to venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe is likely to be contributed to by a missed or delayed diagnosis.2 This delay is thought to be driven primarily by a non-specific disease presentation. The classical triad of dyspnoea, pain on inspiration and haemoptysis is only present in 10% of the patients with PE.3 Instead, PE presentation can range from symptoms mimicking a simple cough or myalgia, an acute myocardial infarction or even nephrolithiasis. This non-specific presentation poses a major diagnostic challenge to physicians to identify PE on time. Prompt recognition of the diagnosis, and consequent immediate initiation of anticoagulant therapy, is important to prevent severe complications and mortality, and is recommended by current guidelines.4 5

The evidence on appropriate strategies to diagnose PE is overwhelming, yet all these strategies by definition start with a suspicion of PE. In contrast, limited evidence is available on the magnitude of delayed PE diagnoses and determinants associated with such diagnostic delay. The current evidence comes largely from studies performed in emergency departments (EDs). These studies identified that diagnostic delay was common, yet with a varying proportion of delayed PE cases (range 12–75% of PE cases).6–13 Furthermore, the definitions used to quantify delay were heterogeneous. Various determinants like higher age, comorbidity (eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cardiovascular disease), absence of dyspnoea and no pain on respiration were associated with a delay in diagnosis, but these findings were not consistent across studies.

In many countries, general practitioners (GPs) fulfil a pivotal gate-keeping role for access to subsequent hospital care. Yet GPs have only limited diagnostic tools available on the spot and often have to rely substantially on clinical assessment. Appreciating the relatively high reported number of PE events missed or delayed in a preselected ED population and the diagnostic limitations in primary care, we hypothesise that delay is likely to be present frequently in primary care as well. However, only one recent publication reports on patient and primary care delay, and on delay-related determinants like comorbidity and the absence of chest pain.14 More evidence on the extent of delay and knowledge on determinants might help GPs to better identify patients with PE on time.

Therefore, the two aims of this study were to explore the extent of diagnostic delay in primary care, and to identify determinants that are associated with this diagnostic delay.

Methods

Study design

We performed an observational study in six primary care practices in the Netherlands. The study was assessed by the local Institutional Ethics Review Board and received a waiver for formal reviewing. As such, according to Dutch law, no explicit informed consent was required as data reducible to the patients were only available at the GP’s practices and made anonymous for data evaluation and analysis by the researchers.

Study population

All patient contacts labelled with the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) code K93 (ie, diagnosis of PE) were extracted from the electronic patient records (EPR) of the six practices. Next, detailed information on all consultations 3 months prior to the PE diagnosis was scrutinised using the following approach. First, all patients with an ICPC code K93 were validated on the actual presence of PE by the researchers (MJM, MK-vR) using hospital discharge information, including results from imaging and medication prescriptions. In case of doubt, another reviewer was consulted (JMTH or GJG). Patients were excluded from further analysis if PE was considered absent, if insufficient information on the PE event was available to confirm the diagnosis, if no objective imaging was performed (eg, in palliative patients) or if the ICPC code was assigned incorrectly in the EPR (eg, if PE was suspected initially, but ruled out after referral and objective imaging). Additionally, the diagnosis PE was confirmed if anticoagulant therapy was initiated postevent and if the hospital discharge letter described the presence of PE based on diagnostic imaging tests.

Outcome: diagnostic delay

We assessed all GP contacts prior to the final diagnosis PE on their relevance in relation to the final PE diagnosis. Patient contacts were considered to be relevant for this PE event when the patient had presented with any of the following signs or symptoms: dyspnoea, cough, haemoptysis, chest pain, painful respiration, fever (body temperature >38°C), increased respiratory rate, increased heart rate, low oxygen saturation or signs of deep venous thrombosis. If data on these items were not reported, we considered them absent. In all other cases (eg, regular diabetes work-up, psychosocial problems), we tagged these contacts as not diagnostically relevant to the final PE diagnosis. Additionally, the initial diagnosis suspected by the GP at the time of the first patient contact, relevant for the final PE event, was registered in all cases. Also, the number of days between the first presentation of any of our predefined signs or symptoms relevant for PE at the GP and the final PE diagnosis was calculated. Cases in which there was any doubt regarding relevance of GP contacts were discussed during consensus meetings (MJM, MK-vR, JMTH and GJG).

The outcome, delay in PE diagnosis, was defined as a period longer than 7 days between the patient's first GP contact attributed to be relevant for PE (based on our aforementioned definition) and the final PE diagnosis, similar to a previous study on diagnostic delay.10 Immediate referral to the ED based on the suspicion of another condition than PE was not considered to be delay, since the severity of the condition was acknowledged.

Potential determinants of diagnostic delay

The following determinants were assessed to be a potential determinant for diagnostic delay: older age (post hoc chosen cut-off >75 years, given the assumption that symptoms are often less specific at higher age), gender, risk factors for PE (ie, recent immobilisation, prior VTE, systemic oestrogen use, pregnancy, puerperium and recent surgery), medical history (ie, COPD, asthma, hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, (past) smoking and malignancy (based on ICPC coding and/or referral letters as recorded in the EPR)).

Statistical analyses

The determinants were first compared between patients with and without a delay in diagnosis in a univariable analysis. Continuous variables were presented as mean (SD) or median (IQR) and compared with the independent sample t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were reported as the absolute number (plus percentage) and compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test.

We then performed multivariable logistic regression analysis using presence or absence of diagnostic delay as the binary outcome to assess which of the potential determinants were independently associated with delayed PE diagnosis. First, we constructed a logistic model using signs and symptoms, age and gender as potential determinants for diagnostic delay. Next, this logistic model was extended with comorbidity in a second model, to gain further insight into the type of patients in whom a delay of diagnosis occurs more often in primary care medicine. Regression coefficients from the logistic models were recalculated into ORs with their surrounding 95% CI.

Given the exploratory nature of this study as well as the uncertainty around the scope of diagnostic delay for PE in primary care, we deliberately chose not to define statistical criteria regarding sample size. Instead, acknowledging the fact that our study sample would not allow for a selection of variables into the logistic models based on p values, we a priori defined the variables that we wanted to assess in the logistic models. This variable selection was entirely based on previous literature review, and included gender, age, absence of chest symptoms (ie, pain on inspiration and chest pain) and the absence of dyspnoea for the first logistic model, and additionally a prior respiratory chest infection and asthma/COPD for the second logistic model. It should be noted that there is a potential risk of overfitting when including too many variables into a logistic models in respect of the number of delayed cases. Therefore, the second model is regarded to be only an extension to the first model to explore the influence of knowledge on comorbidity and should be interpreted as such. Data were analysed using SPSS V.21.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

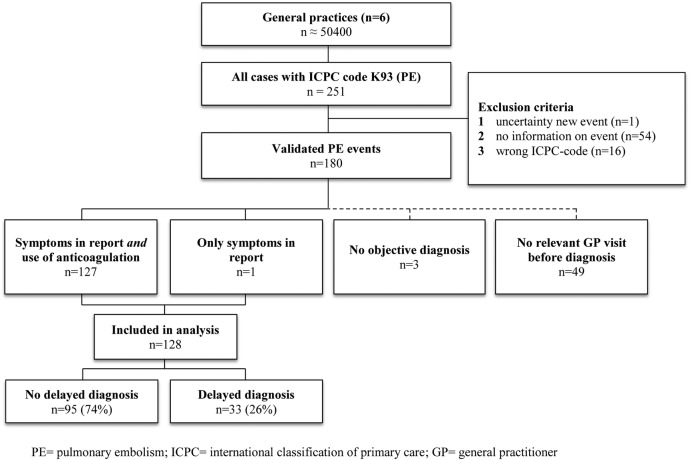

Approximately 50 400 patients were registered in the six general practices that participated. Using the ICPC code K93, 251 possible PE cases were identified, with varying starting dates per practice due to logistical reasons (first PE event 1994) until June 2015. Seventy-one cases were excluded based on the predefined exclusion criteria. For the majority of cases (n=54), no detailed information was available, for example, if the event took place years ago while registered in another practice. In total, 180 verified PE cases were left for further analyses (see figure 1). Forty-nine patients (27%) had no contact with their GP prior to the PE event and in three (palliative care) patients no objective imaging was performed. See table 1 for further characteristics of the group of patients that did not contact their GP in the period prior to the PE diagnosis. This latter group included more patients with a recent surgery, active malignant disease, but less patients with cardiac or respiratory comorbidities. The remaining 128 patients had relevant contact moments with their GP prior to the diagnosis and were included in our main analysis. In 33 of these patients (26%), diagnostic delay as defined a priori was observed.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the selection of pulmonary embolism cases in primary care.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with and without GP visit before diagnosis PE

| No prior GP visit (n=49) | Prior GP contact(s) (n=128) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years,* mean (±SD) | 60 (17) | 58 (16) | 0.429 |

| Male gender | 27 (55) | 60 (47) | 0.327 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| COPD/asthma | 5 (10) | 27 (21) | 0.067† |

| Hypertension | 11 (22) | 37 (29) | 0.387 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 (2) | 4 (3) | 1.000† |

| Congestive heart failure | 0 (0) | 6 (5) | 0.189† |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 3 (6) | 14 (11) | 0.406† |

| Risk factors | |||

| History of DVT | 7 (14) | 26 (20) | 0.357 |

| Recent surgery | 8 (16) | 8 (6) | 0.045† |

| Recent immobilisation | 4 (8) | 6 (5) | 0.467† |

| Recent travelling | 2 (4) | 4 (3) | 0.669† |

| Malignancy | 9 (18) | 10 (8) | 0.042 |

| Oestrogen use, women | 0/22 (0) | 19/68 (28) | 0.005† |

| Prior pulmonary infection | 3 (6) | 23 (18) | 0.057† |

| History of smoking | 6 (12) | 33 (26) | 0.052 |

| Pregnancy | 0/22 (0) | 3/68 (4) | 1.000 |

| Days until diagnosis, median (IQR) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | |

| Total range | NA | 0–126 days | |

| Delay >7 days | NA | 33 (26) | |

Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise.

*Missing values (n=3).

†Fisher's exact test

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; GP, general practitioner; NA, not applicable; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Patients with a delay in diagnosis were on average older, had less frequent chest pain (24% vs 54%, p=0.003) and less frequent pain on respiration (9% vs 33%, p=0.011) on initial presentation. Diagnosis was more often delayed in patients with a recent respiratory tract infection (33% vs 13%, p=0.008; see table 2). In the first multivariable logistic regression analysis, older age (OR 5.1 (95% CI 1.8 to 14.1)) and the absence of chest symptoms (OR 5.4 (95% CI 1.9 to 15.2)) were associated with diagnostic delay (see table 3). In the second model, female gender, absence of dyspnoea and prior respiratory tract infections were associated with delay in diagnosis too (see table 4).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics (diagnostic delay >7 days)

| No diagnostic delay (n=95) | Diagnostic delay >7 days (n=33) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years,* mean (±SD) | 56 (15) | 62 (18) | 0.068 |

| Age >75 years | 12 (13) | 15 (46) | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 47 (49) | 13 (39) | 0.317 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Dyspnoea | 62 (65) | 22 (67) | 0.884 |

| Chest symptoms | 59 (62) | 9 (27) | 0.001 |

| Chest pain | 51 (54) | 8 (24) | 0.003 |

| Painful respiration | 31 (33) | 3 (9) | 0.011† |

| Cough | 17 (18) | 12 (36) | 0.029 |

| Haemoptysis | 3 (3) | 1 (3) | 1.000† |

| Signs of DVT | 18 (19) | 1 (3) | 0.025† |

| Fever (>38°C) | 5 (5) | 2 (6) | 1.000† |

| Collapse | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.572† |

| Heart rate, mean (±SD) | 96 (19) | 95 (26) | 0.916 |

| O2 saturation, median (IQR) | 96 (5) | 94 (9) | 0.124 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| COPD and/or asthma | 14 (15) | 13 (39) | 0.004 |

| Hypertension | 25 (26) | 12 (36) | 0.273 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 (2) | 2 (6) | 0.273† |

| Congestive heart failure | 3 (3) | 3 (9) | 0.177† |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 10 (11) | 4 (12) | 0.755† |

| Risk factors | |||

| History of DVT | 18 (19) | 8 (24) | 0.515 |

| Recent surgery | 7 (7) | 1 (3) | 0.679† |

| Recent immobilisation | 6 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.338† |

| Recent travelling | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.572† |

| Malignancy | 7 (7) | 3 (9) | 0.717† |

| Oestrogen use, women | 15/48 (31) | 4/20 (20) | 0.393† |

| Prior pulmonary infection | 12 (13) | 11 (33) | 0.008 |

| History of smoking | 26 (27) | 7 (21) | 0.486 |

| Pregnancy | 3/48 (6) | 0/20 (0) | 0.550 |

Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise.

*Missing values (n=3).

†Fisher's exact test

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; NA, not applicable; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression model for the association between signs and symptoms with a diagnostic delay >7 days

| Model 1 | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 2.5 (0.9 to 6.6) | 0.071 |

| Age >75 | 5.1 (1.8 to 14.1) | 0.002 |

| No chest symptoms | 5.4 (1.9 to 15.2) | 0.002 |

| No dyspnoea | 2.3 (0.8 to 6.5) | 0.118 |

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression model for the association between signs, symptoms and comorbidity with a diagnostic delay >7 days

| Model 2 | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 3.1 (1.1 to 8.8) | 0.036 |

| Age >75 | 4.3 (1.5 to 12.3) | 0.007 |

| No chest symptoms | 5.4 (1.8 to 16.1) | 0.003 |

| No dyspnoea | 3.1 (1.0 to 9.4) | 0.047 |

| Prior respiratory tract infection | 3.3 (1.1 to 10.0) | 0.031 |

| COPD/asthma | 3.3 (0.9 to 7.5) | 0.085 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Discussion

In this study on the extent of diagnostic delay of PE in primary care and its determinants, we observed that diagnostic delay was present in a substantial proportion of patients (26%). An important factor associated with diagnostic delay appeared to be the absence of the typical ‘text book’ chest pain symptoms as presented during the first presentation at the GP. Furthermore, in those with diagnostic delay, a respiratory tract infection was frequently reported, before the initial PE diagnosis was established.

This is one of the first studies on the magnitude of diagnostic delay of PE in a primary care setting. The strength of this study is the fact that we had access to the GP's electronic patient records, including all consultations with the GP prior to the diagnosis, plus the correspondence between GPs and hospital specialists and all results from laboratory and imaging tests performed. This allowed us to sketch a complete and detailed picture of the diagnostic pathway starting from the first presentation of patients with signs and symptoms at their GP to the final diagnosis of PE.

However, for full appreciation of these results, some limitations need to be addressed. Of note, we used a retrospective design to quantify diagnostic delay, which incurs several challenges.

First, we had to rely on correct ICPC coding in all primary care practices. Only cases with the ICPC code K93 were extracted for detailed assessment, leaving the chance of erroneously leaving out PE cases that were labelled with an incorrect ICPC code. This could be the case if a patient is referred to secondary care with non-specific symptoms like dyspnoea, consequently coded as such, without updating of the coding to PE afterwards. We, however, believe that this miscoding will be present only in a fraction of all PE cases, given that PE is an important diagnosis to be reported for further anticoagulant use and because of its prognostic implications. Another reason for incomplete selection of PE cases is the fact that patient records of those deceased were not available for all. This leaves the chance of missing PE events in patients that occurred in the years prior to their passing.

Second, data on determinants like oxygen saturation, heart rate and D-dimer levels were not reported in the patient records of many cases. For the current analyses, we assumed that the variable was not present if information on that item was not reported. However, it cannot be said for sure if these variables were not measured at all, or absent if not reported. Especially if PE is not suspected by the GP, it can be expected that not all PE risk factors and signs (eg, recent travelling or respiratory rate) are explicitly asked. If so, this can lead to selective under-reporting of specific determinants. In an attempt to gain insight into the possible selective reporting, we performed a sensitivity analysis in which we tested for the distribution of non-reported factors between the patients with and without delay. No substantial differences were observed, however (data not shown).

Third, we had to make interpretations on the relevance of certain symptoms for the diagnosis of PE, all with current knowledge that PE was indeed present. Blinding can only be achieved with extensive measures in a retrospective design, for example, using patients with other final diagnoses as controls. In further research, such blinding strategies should be considered.

Fourth, we used data from six different GP practices with distinct patient characteristics. Given the small number of cases, and the even smaller number of delayed cases, per practice, we decided not to assess practice effects on top of our first two models. Nevertheless, the extent of diagnostic delay seems to be rather homogeneous (around 30%) across the practices under study, and therefore we believe that our inferences are likely to be generalisable to at least primary care practices working in a similar healthcare setting like the UK, Ireland and Scandinavia.

Nevertheless, being aware of all these drawbacks of using a retrospective study design, we deemed this design to be the most suitable method to study delay in diagnosis. By definition, delay is only to be determined with hindsight and, as a consequence, prospective evaluation of the diagnostic process will be difficult for a disease with a relatively low incidence in primary care.

We arbitrarily defined diagnostic delay as a time lag of >7 days between the first presentation at the GP and the final diagnosis. However, a lag period of >7 days can be deemed to be too large, especially considering the potentially fatal outcome of not treating a PE event on time.5 Therefore, we performed a sensitivity analysis in which we set the definition of diagnostic delay at one or more GP contacts without adequate referral to secondary care for further diagnostics. Using this (more stringent) definition of diagnostic delay, the proportion of cases missed increased to over 40% (see online supplementary material). Yet the inferences on our reported determinants of delay remained rather constant, strengthening the validity of our findings.

bmjopen-2016-012789supp.pdf (136.9KB, pdf)

Another complicating factor in the definition of delay in PE diagnosis concerns its physiological development and progression. In recent years, much has been written on the interplay of inflammation and an activated thrombogenic state.15 16 Thus, an infection could also be the precursor of, and provoking factor for, PE. An initial diagnosis of a respiratory tract infection that turns out to be a PE a few days later is not necessarily a delayed PE diagnosis. Instead, the PE can rather be the result of a cascade initiated by the infection. This distinction between a PE initiated by an infection and a PE incorrectly diagnosed as an infection cannot be made easily, leaving the chance of overestimation of the association between diagnostic delay and a respiratory tract infection. This possible interplay between infection and venous thrombosis was also observed the other way around in a recent case–control study by Timp et al17 including over 2500 patients with VTE. Patients receiving antibiotics (as a proxy for infectious disease) had an increased risk of first and recurrent VTE (incidence rate ratio (IRR) 5.6 (95% CI 4.6 to 6.8); 127 patients with VTE while on antibiotics). Analogous to our inferences, this point estimate may have been too high due to misclassification of PE symptoms as an infection and thus inappropriate prescription of antibiotics. After exclusion of those patients in whom misclassification was very likely, the IRR remained 5.0 (95% CI 4.0 to 6.1). The latter in fact would be classified as delay in diagnosis in our study.

In seven PE cases without diagnostic delay, the diagnosis of PE was not considered initially by the GP. However, owing to the suspicion of another serious condition (acute coronary event), urgent referral to the ED led to prompt diagnosis of PE anyhow. In the strict sense of the definition, the diagnosis of PE is missed here since it was not the diagnosis deemed to be most likely by the GP. We treated these missed, but adequately referred, cases as ‘delay present’ in a sensitivity analysis, not changing our inferences (data not shown).

Finally, we did not collect data on the clinical implications of diagnostic delay, like quality of life or long-term health effects. However, knowledge on the impact of delay on clinical outcomes is important to be able to value the relevance of delayed diagnoses: it can be hypothesised that long-term outcomes are worse for patients who have had a prolonged duration of symptoms, caused by the lengthened exposure to vessel obstruction, and consequent vessel damage, pulmonary hypertension or lung infarction. Further prospective research, however, is needed to address this research question for the primary care domain.

Comparison with other studies

A few studies on delay in diagnosis of PE have been performed in secondary care, especially in EDs. For example, Torres-Macho and colleagues found that diagnostic delay was present in 146/436 (33.5%) cases with PE at a Spanish ED. Patients were older (71.5 years (SD 15.2) vs 67.3 years (SD 13.7; p=0.04)) and had more frequently COPD (29.7% vs 7.25% (p≤0.001)) or asthma (11.7% vs 4.1% (p=0.01)) if PE was diagnosed during hospitalisation after ED examination. Patients who were sent home with a wrong diagnosis presented more often with a cough (25.9% vs 13.4% (p=0.01)) and fever (18.5% vs 5.1% (p=0.002)).8 In the study by Alonso-Martinez and colleagues, a delay in diagnosis longer than 6 days was present in 50% of cases (186/375 patients). The number of days of delay was higher among the elderly (median days of delay 7 (IQR 13) if age ≥65 vs 4 (IQR 5) if age <65 years (p≤0.01)), and in those with previous cardiac disease and without sudden onset of dyspnoea.6 In our study, older age was associated with diagnostic delay too, just like the absence of typical PE symptoms. However, female gender was not reported previously in relation with delay. Only one study mentioned female gender as a risk factor for patient delay rather than doctor delay.13 Given our small sample size and exploratory nature, these findings require further evaluation in future research. A recent retrospective study was conducted in a Dutch secondary care setting in which delay in primary care was estimated as well. Whereas 75% of patients were referred within 1 day, the remaining 25% had an average delay of 15.7 days.14 One important determinant for early referral was the presence of chest pain. This is in line with our results, in which the absence of chest symptoms was associated with diagnostic delay.

Clinical implications

Given the substantial percentage of cases with delay in diagnosis of PE observed in this study, we assume that most GPs come across a situation with diagnostic delay in PE regularly. Even if an alternative diagnosis is confirmed (eg, infiltrate on chest radiography, or an initial improvement after the initiation of antibiotic treatment), PE can be present simultaneously, or develop along the course of the concurrent disease. Therefore, we argue that an initial diagnosis should be reconsidered frequently, especially if symptoms do not improve as much as can be expected, and in those with coexisting cardiopulmonary conditions.

Furthermore, we showed in this study that the diagnosis of PE is more often delayed in case of non-typical presentation of symptoms. Therefore, we suggest that GPs consider PE as a potential diagnosis even if symptoms are not overwhelmingly pointing in that direction. To prevent an overshoot of referrals to secondary care as a consequence of this low threshold of suspicion, a diagnostic prediction model might help GPs to further guide the decision whether or not to refer a patient.18 Nevertheless, especially in the elderly and in those with concurrent respiratory tract infections, the false-positive rate of these prediction models (specifically the D-dimer test) is considerable.19 20 As such, the optimal balance between raised awareness of PE and refraining from over-referral has yet to be found and further evaluation of diagnostic delay is needed.

Conclusion

Diagnostic delay of PE is common in primary care, especially if classical PE symptoms like chest symptoms are absent. Awareness of the possibility of a PE being the underlying cause of a wide range of symptoms might contribute to a reduction in the number of delayed PE diagnoses in primary care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following general practices and GPs for their participation in this project: Praktijk Buitenhof, Amsterdam; S van Doorn, MD, Praktijk Spechtenkamp, Maarssen; F Rutten, MD, PhD, Huisartsenpraktijk de Grebbe, Rhenen; J Morgenstern, MD, Huisartsenpraktijk Heerde; R Damoiseaux, MD, PhD, Hof van Blom, Hattem; C Hoppenreijs, MD, Gezondheidscentrum Binnenstad, Utrecht.

Footnotes

Contributors: JMTH, G-JG and KGMM were involved in conception and design of the work. JMTH, MK-vR, MJM and G-JG were involved in data collection. JMTH, MK-vR, MJM, G-JG and KGMM were involved in data analysis and interpretation. JMTH, MK-vR, MJM and G-JG were involved in drafting the article. REGS, RO and KGMM were involved in critical revision of the article. JMTH, MK-vR, MJM, RO, REGS, KGMM and G-JG were involved in final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: G-JG is supported by a VENI grant (91616030) from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). NWO had no influence on the writing, concept, study design or inferences of this study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: IRB UMC Utrecht.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data set and statistical codes are available from the authors on request.

References

- 1.Schiff GD, Hasan O, Kim S et al. . Diagnostic error in medicine: analysis of 583 physician-reported errors. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1881–7. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen AT, Agnelli G, Anderson FA et al. . Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe—the number of VTE events and associated morbidity and mortality. Thromb Haemost 2007;98:756–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer G, Roy PM, Gilberg S et al. . Pulmonary embolism. BMJ 2010;340:c1421 10.1136/bmj.c1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NICE. Diagnosis and management of venous thromboembolic diseases. NICE quality standard 29. Manchester: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douketis JD, Kearon C, Bates S et al. . Risk of fatal pulmonary embolism in patients with treated venous thromboembolism. JAMA 1998;279:458–62. 10.1001/jama.279.6.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alonso-Martínez JL, Sánchez FJA, Echezarreta MAU. Delay and misdiagnosis in sub-massive and non-massive acute pulmonary embolism. Eur J Intern Med 2010;21:278–82. 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith SB, Geske JB, Morgenthaler TI. Risk factors associated with delayed diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism. J Emerg Med 2012;42:1–6. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torres-Macho J, Mancebo-Plaza AB, Crespo-Giménez A et al. . Clinical features of patients inappropriately undiagnosed of pulmonary embolism. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:1646–50. 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kline JA, Hernandez-Nino J, Jones AE et al. . Prospective study of the clinical features and outcomes of emergency department patients with delayed diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Acad Emerg Med 2007;14:592–8. 10.1197/j.aem.2007.03.1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.den Exter PL, van Es J, Erkens PMG et al. . Impact of delay in clinical presentation on the diagnostic management and prognosis of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:1369–73. 10.1164/rccm.201212-2219OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozsu S, Oztuna F, Bulbul Y et al. . The role of risk factors in delayed diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Am J Emerg Med 2011;29:26–32. 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ageno W, Agnelli G, Imberti D et al. . Factors associated with the timing of diagnosis of venous thromboembolism: Results from the MASTER registry. Thromb Res 2008;121:751–6. 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aydogdu M, Dogan NÖ, Sinanoğlu NT et al. . Delay in diagnosis of pulmonary thromboembolism in emergency department: is it still a problem? Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2013;19:402–9. 10.1177/1076029612440164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walen S, Damoiseaux RA, Uil SM et al. . Diagnostic delay of pulmonary embolism in primary and secondary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e444–50. 10.3399/bjgp16X685201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delvaeye M, Conway EM. Coagulation and innate immune responses: can we view them separately? Blood 2009;114:2367–74. 10.1182/blood-2009-05-199208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tichelaar YIGV, Kluin-Nelemans HJC, Meijer K. Infections and inflammatory diseases as risk factors for venous thrombosis. A systematic review. Thromb Haemost 2012;107:827–37. 10.1160/TH11-09-0611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timp J, Cannegieter S, Tichelaar V et al. . Risk of first and recurrent venous thrombosis in individuals treated with antibiotics. J Thromb Haemost 2015;13:983 10.1111/jth.12993 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geersing GJ, Erkens PMG, Lucassen W et al. . Safe exclusion of pulmonary embolism using the Wells rule and qualitative D-dimer testing in primary care: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2012;345:e6564 10.1136/bmj.e6564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schouten HJ, Geersing GJ, Koek HL et al. . Diagnostic accuracy of conventional or age adjusted D-dimer cut-off values in older patients with suspected venous thromboembolism: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2013;346:f2492 10.1136/bmj.f2492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harper PL, Theakston E, Ahmed J et al. . D-dimer concentration increases with age reducing the clinical value of the D-dimer assay in the elderly. Intern Med J 2007;37:607–13. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012789supp.pdf (136.9KB, pdf)