Abstract

Objectives

Dyslipidaemia is one of the main risk factors for cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in Malaysia. This study assessed the awareness, knowledge and practice of lipid management among primary care physicians undergoing postgraduate training in Malaysia.

Design

Cross sectional study.

Setting

Postgraduate primary care trainees in Malaysia.

Participants

759 postgraduate primary care trainees were approached through email or hard copy, of whom 466 responded.

Method

A self-administered questionnaire was used to assess their awareness, knowledge and practice of dyslipidaemia management. The total cumulative score derived from the knowledge section was categorised into good or poor knowledge based on the median score, where a score of less than the median score was categorised as poor and a score equal to or more than the median score was categorised as good. We further examined the association between knowledge score and sociodemographic data. Associations were considered significant when p<0.05.

Results

The response rate achieved was 61.4%. The majority (98.1%) were aware of the national lipid guideline, and 95.6% reported that they used the lipid guideline in their practice. The median knowledge score was 7 out of 10; 70.2% of respondents scored 7 or more which was considered as good knowledge. Despite the majority (95.6%) reporting use of guidelines, there was wide variation in their clinical practice whereby some did not practise based on the guidelines. There was a positive significant association between awareness and the use of the guideline with knowledge score (p<0.001). However there was no significant association between knowledge score and sociodemographic data (p>0.05).

Conclusions

The level of awareness and use of the lipid guideline among postgraduate primary care trainees was good. However, there were still gaps in their knowledge and practice which are not in accordance with standard guidelines.

Keywords: awareness, knowledge and practice; primary care physician

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first study to assess this area among primary care physicians in Malaysia.

This study involved participants from throughout Malaysia, and included primary care trainees working in hospitals, government clinics as well as private general practice, and hence provided information of performance across various sectors.

The response rate was 61.4% so the performance of a substantial proportion of those invited to participate is unknown.

The questionnaire developed for this study used vignettes as one of the ways to assess knowledge, although clinical vignettes could never be the same as actual real-life practice in which more history as well as physical findings and other information are available.

Some other aspects of lipid management such as other types of dyslipidaemia (high triglycerides and low high-density lipoprotein) as well as non-pharmacological management of dyslipidaemia were not covered in this study.

Introduction

Dyslipidaemia is one of the main risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD).1–3 It contributes more than half of global ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and 18% of global cerebrovascular disease.4 CVD is also the leading cause of death in Malaysia.5 National data showed that 33% of patients who had acute coronary syndrome had already been diagnosed as having dyslipidaemia before their event.6 Optimum management of dyslipidaemia will therefore have great potential for reducing the number of CVD events in Malaysia.

Several studies have reported that many patients with dyslipidaemia were not on any lipid lowering drugs. Even among those patients who were on lipid lowering agents, the prevalence of those who achieved the desired lipid level was low. A study in China reported that only 23% of patients with dyslipidaemia received treatment and only 17% achieved the desired lipid level of control.7 Another study among Hispanic/Latinos in the USA also reported only 29.5% patients with dyslipidaemia were receiving lipid lowering treatment.8 Furthermore, a study in Canada among patients with moderate to high Framingham risk scores found that many of them were not receiving a statin.9 A local study, using the Pooled Cohort Risk Score in primary care patients to identify the need for statins, reported that there was both underuse of statin therapy in those who required it and overuse of statins in those who did not qualify for it.10 All these findings suggest suboptimal lipid management in different continents. Therefore, it would be of interest to investigate possible contributing factors influencing primary care physicians in their management of dyslipidaemia.

A study in China revealed that both the level of awareness of their national lipid guideline as well as management of dyslipidaemia among community physicians working in primary care were poor.3 On the other hand, a US study reported that primary care physicians had a very high level of awareness (>90%) and were very knowledgeable about managing dyslipidaemia.11 However, another US study involving primary care physicians reported that just one third of them actually adhered to the recommendations of the guideline on lipid management.1 It would therefore be of interest and importance to ascertain the performance of our primary care physicians in Malaysia. To date, no such study has been undertaken in this country.

As the majority of patients with dyslipidaemia are treated by primary care physicians, this study chose to focus on trainees in primary care as they are currently undergoing postgraduate training and will be the future trained primary care specialists who will be expected to lead other physicians working in primary care. The objective of this study was to examine the awareness, knowledge and practice of lipid management among postgraduate primary care trainees. The association between their knowledge and sociodemographic data was also examined. The assumption before this study was that these trainees should have a good level of awareness, knowledge and clinical practice in managing patients with dyslipidaemia. A study in Spain reported that the cardiovascular training programme conducted for primary care professionals (physicians and nurses) significantly improved the recording of the cardiovascular risk factors among them.12 Hence, we expected the same finding from this study and the results should help guide the training of our primary care physicians.

Method

Population and setting

This was a cross sectional study conducted from September to December 2015 among primary care trainees. These trainees were recruited from the Diploma in Family Medicine (DFM) programme, the Advance in Primary Care Training Programme (ATP), and the Master in Family Medicine programme. The inclusion criteria were primary care physicians who were currently undergoing postgraduate primary care training. The exclusion criteria were trainees who were absent from work during the period of the study (eg, prolonged medical leave, maternity leave or unpaid leave).

Sample size

Several studies have shown that the prevalence of awareness of physicians about lipid guidelines ranged from 12% to 90%. This is a very wide range and therefore to allow for maximum variation, we chose a prevalence of 50%. Using the Kish formula13 to calculate our sample size with p=0.50 the calculated sample size was 384. This study mainly involved delivery of the questionnaire through email with an expected response rate of 25–30%, although the response may double up with subsequent email reminders.14 We planned to send reminders, so in order to achieve at least 384 participants, we aimed to approach double the calculated sample size (2×384=786 participants). However, as there were only 759 primary care postgraduate trainees available in Malaysia, all eligible trainees were approached.

Instrument

The questionnaire for this study was developed based on the Malaysia Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) on Management of Dyslipidaemia 2011,5 and the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults.15 The questionnaire comprised the following sections: sociodemographic profile of the participants, awareness and use of lipid guidelines, knowledge and practice of lipid management based on vignette/clinical scenario. Content and face validation was performed to improve the adequacy, accuracy and appropriateness of the questionnaire.

Participants were approached via their training centres. Data collection for this study was done in two ways. For trainees who were from the same centre as the authors, where we had daily contact, these trainees were given the hard copy version. For all others who were at different training centres throughout the country, the email version was used. The majority was through email.

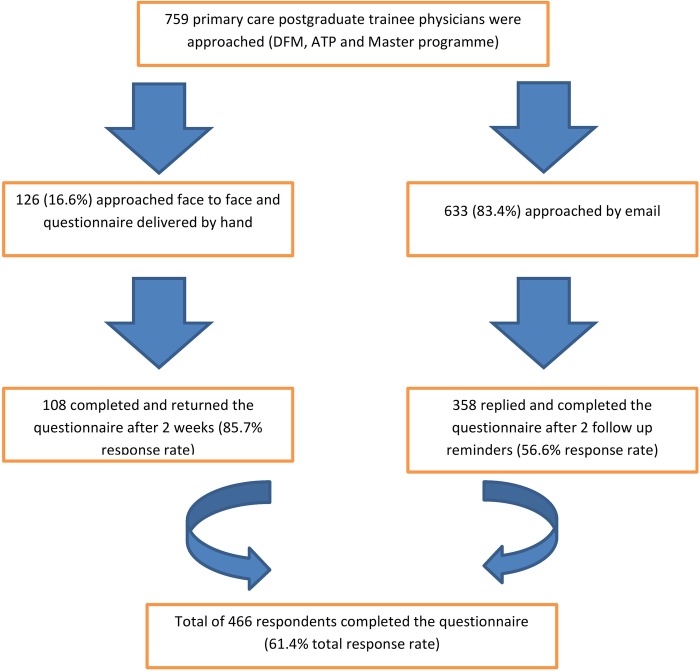

Participants who were approached face to face were given the consent form and the information sheet. The questionnaires were then collected after 2 weeks. For the email version, the information on the study was provided through the email and the participants were informed that by completing the questionnaire and returning them, it will serve as their consent for the study. In addition, for the email version, the questionnaire was emailed again to the participants up to three times if they did not respond to the initial email. Thus, the initial email was followed up with two subsequent emails 2 weeks apart if there was no response. This was done to maximise the response rate. The response rate is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of data collection. ATP, Advance in Primary Care Training Programme; DFM, Diploma in Family Medicine.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was done using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) V.22. The data were cleaned and checked for accuracy. Pearson's χ2 test was used to test for association between two categorical data. Test of normality was performed for continuous data. The not normally distributed data were expressed using median and interquartile range. Association between not normally distributed data and categorical data was done using the Mann-Whitney U test. The total cumulative score was calculated from the knowledge section of the questionnaire. There were 10 questions for this section; each correct answer was given 1 point and there was no deduction of points for the wrong answer. The minimum possible score was 0 and the maximum possible score was 10. To test for association between knowledge score and sociodemographic data, the total cumulative score was categorised into good or poor knowledge based on median score16–18 where a score less than the median score was categorised as poor and a score equal to or more than the median score was categorised as good. Associations were considered significant at a value of p<0.05.

Ethics

This study was approved by the University Malaya Medical Centre Ethics Committee (reference number 20156–1435) on 10 July 2015 before initiation of the study. All the heads of the different postgraduate training programmes were contacted to seek permission to do the study. The head of the Academy of Family Physicians Malaysia (AFPM) followed by the head of the DFM and ATP programmes were contacted and permission to conduct the study was granted by them. As for the master programmes, the respective heads of the primary care departments from the five universities involved were contacted and permission was also granted before the study was conducted.

Results

A total of 759 participants were approached (through email and hard copy) (figure 1); 466 responded (61.4% response rate).

Demographic characteristic of participants

The sociodemographic data of the respondents are shown in table 1. It shows that more than two thirds of respondents were female, half of them working in government clinics. The ethnicity ‘others’ comprise Sarawakian, Sabahan and foreigners. The median age was 32 years and the median years of practice in an outpatient setting was 4 years.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic data of respondents

| Respondents profile | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender (n=463) | |

| Male | 121 (26.1) |

| Female | 342 (73.9) |

| Median age in years (IQR) (range) |

32 (4) (27–63) |

| Ethnicity (n=460) | |

| Malay | 183 (39.8) |

| Chinese | 137 (29.8) |

| Indian | 125 (27.2) |

| Others | 15 (3.2) |

| Years of practice in primary care setting | |

| Median (IQR) (range) |

4 (4) (1–36)* |

| Number of patients seen per day (n=466) | |

| <20 | 27 (5.8) |

| 21—40 | 173 (37.1) |

| 41—60 | 156 (33.5) |

| 61–80 | 70 (15.0) |

| 81–100 | 35 (7.5) |

| >100 | 5 (1.1) |

| Current working sector (n=461) | |

| Government clinic | 236 (50.8) |

| General practitioner | 127 (27.3) |

| Hospital | 102 (21.9) |

*One of the respondents has been working as a general practitioner for 36 years and is currently undergoing the Diploma in Family Medicine (DFM) programme, a recent online postgraduate programme offered by the national Academy of Family Medicine.

Awareness, knowledge and practice on management of dyslipidaemia

The awareness and use of the lipid guideline among respondents was very high (table 2). Almost all the participants were aware of the Malaysian CPG on lipid management. More than three quarters (78.6%) of them were also aware of the AHA guideline. The majority (95.6%) of them used lipid guidelines with >90% using our national CPG as their guideline.

Table 2.

Awareness and use of lipid guidelines among respondents

| Awareness and use of lipid guidelines | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Awareness of Malaysian CPG on management of dyslipidaemia (n=465) | |

| Yes | 456 (98.1) |

| No | 9 (1.9) |

| Awareness of AHA guideline on treatment of blood cholesterol (n=463) | |

| Yes | 364 (78.6) |

| No | 99 (21.4) |

| Use any lipid guidelines. (n=460) | |

| Yes | 440 (95.6) |

| No | 20 (4.4) |

| Guidelines use (participants can choose more than one) (n=466) | |

| Malaysian CPG | 429 (92.1) |

| AHA guideline* | 87 (18.7) |

| ATP III guideline† revised 2008 | 11 (2.4) |

| NICE guideline‡ 2008 | 42 (9.0) |

| Others§ | 1 (0.2) |

*American Heart Association (AHA) guideline 2013 on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) risk.

†Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) 2008.

‡National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline on lipid modification 2008.

§The participant did not specify the guideline used.

ATP, Advance in Primary Care Training Programme; CPG, Clinical Practice Guideline.

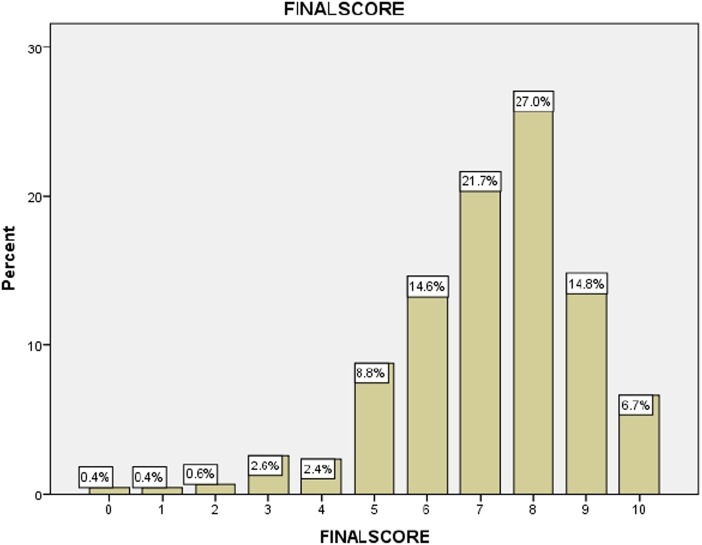

Table 3 shows 10 questions assessing their knowledge on the management of dyslipidaemia together with the percentage of respondents who gave the correct answer to each question; 70.2% of respondents scored equal to or more than the median score which was categorised as good knowledge (figure 2).

Table 3.

Knowledge on management of dyslipidaemia

| Questions/scenarios | n (%) |

|---|---|

|

377 (81.6) |

|

396 (85.7) |

|

250 (53.8) |

|

348 (75.7) |

|

328 (71.1) |

|

436 (93.6) |

|

313 (71.8) |

|

436 (93.8) |

|

139 (31.9) |

|

308 (66.5) |

AHA, American Heart Association; DM, diabetes mellitus; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Figure 2.

Total cumulative knowledge score.

There was a positive significant association between the knowledge score and their awareness as well as use of the lipid guideline (p<0.001). However, there was no significant association between the knowledge score with sociodemographic data (p>0.05) (table 4).

Table 4.

Association between knowledge score and sociodemographic profile

| Knowledge n (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic profile | Poor | Good | p Value |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 31 (25.6) | 90 (74.4) | |

| Female | 108 (31.6) | 234 (68.4) | 0.25 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Malay | 45 (24.6) | 138 (75.4) | |

| Chinese | 42 (30.7) | 95 (69.3) | 0.14 |

| Indian | 46 (36.8) | 79 (63.2) | |

| Others | 5 (33.3) | 10 (66.7) | |

| Age (years) ±SD | 33.3±4.6 | 33.8±4.7 | 0.07 |

| Years of practice (years) ±SD | 4.6±4.1 | 5.2±4.3 | 0.09 |

| Working sectors | |||

| Government clinic | 71 (30.1) | 165 (69.9) | |

| General practitioners | 43 (33.9) | 84 (66.1) | 0.31 |

| Hospital | 25 (24.5) | 77 (75.5) | |

| Number of patients per day | |||

| <20 | 9 (33.3) | 18 (66.7) | |

| 21–40 | 46 (26.6) | 127 (73.4) | 0.18 |

| 41–60 | 43 (27.6) | 113 (72.4) | |

| 61–80 | 22 (31.4) | 48 (68.6) | |

| 81–100 | 17 (48.6) | 18 (51.4) | |

| >100 | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | |

| Awareness of Malaysian CPG | |||

| Yes | 130 (28.6) | 324 (71.4) | |

| No | 9 (81.8) | 2 (18.2) | <0.001 |

| Use of guideline | |||

| Yes | 122 (27.4) | 323 (72.6) | <0.001 |

| No | 17 (81.0) | 4 (19.0) | |

CPG, Clinical Practice Guideline.

There was wide variation of practice among respondents as shown in table 5. This included ordering unnecessary investigations before initiating statin therapy. Ezetimibe, gemfibrozil and fenofibrate were the three most commonly used drugs in combination with a statin. The majority of the respondents used a cardiovascular risk calculator to determine the cardiovascular risk score before initiating statin therapy.

Table 5.

Practice among respondents

| Questions | n (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. Investigations before initiating statin (can choose more than one) | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | 344 (73.8) |

| Full blood count | 26 (5.6) |

| Renal profile (electrolyte, urea and creatinine) | 119 (25.5) |

| Fasting blood glucose | 113 (24.2) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | 452 (91.2) |

| Creatine kinase | 103 (22.1) |

| 2. If a patient on statin therapy developed unexplained severe muscle symptoms/fatigue. What will you do? | |

| Stop statin and investigate | 313 (68.3) |

| 3. Additional drug after statin failed to achieve target (can choose more than one) | |

| Niacin | 40 (8.6) |

| Ezetimibe | 239 (51.3) |

| Gemfibrozil | 195 (41.8) |

| Fenofibrate | 204 (43.8) |

| Others | 3 (0.6) |

| 4. Do you use cardiovascular risk calculator to calculate cardiovascular risk before initiating statin? (n=463) | |

| Yes | 369 (79.7) |

| No | 94 (20.3) |

Bold indicates correct answer.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

The results of this study showed that almost all (98.1%) of the respondents were aware of the national lipid guideline. The majority of the respondents (95.7%) reported that they used lipid guidelines. This was much higher compared to a US study which revealed only about 50% of the primary care physicians used their national guideline.19 The reason for this could be that our study population comprised postgraduate trainees who would be more up-to-date with all the available guidelines. A larger study, involving primary care physicians from other countries including Singapore, Portugal and the UK, revealed that 81% of the physicians used lipid guidelines to set the cholesterol target.20

The majority of respondents gave the correct answer for almost all 10 questions in this section; the exception was question 9, which asked about the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) target for the patient with both diabetes mellitus and IHD, where only 31.9% of respondents gave the correct answer. A high proportion (81.6%) of respondents gave the correct answer in regard to initiating statin therapy for patients with underlying IHD as secondary prevention (question 1). The majority of them also managed to risk stratify patients correctly as low and high risk patients (questions 4 and 5). Although >90% reported use of the lipid guidelines as mentioned above, the cumulative knowledge score was only good in 70.2% of our trainees, suggesting residual gaps about lipid management. Awareness and use of lipid guidelines correlated positively with knowledge score in this study. This result is consistent with a study which showed that poor awareness of lipid guidelines resulted in poor knowledge among physicians.3 There was, however, no significant association between knowledge score and the sociodemographic data of the respondents.

In terms of practice, the majority of the respondents (91.2%) correctly ordered alanine aminotransferase (ALT) before initiating statin. At the same time, there was also a wide variation of practice among the participants. Some of them ordered unnecessary investigations before initiating statin therapy, including renal profile (25.5%), creatine kinase (22.1%) and full blood count (5.6%). This practice could result in a waste of unnecessary resources. Nearly a quarter of respondents (24.2%) also ordered fasting blood glucose before statin initiation. This could be due to the fear of statin induced diabetes mellitus as stated in several reports.21 22

A question that assessed the ability to recognise and manage the possibility of statin induced rhabdomyolysis raised some concern among the authors. The failure to manage this could be fatal for the patient. Unfortunately, only about two thirds of the respondents (68.3%) gave the correct answer. Hence, this important aspect should be highlighted and emphasised further in training.

Most of the respondents chose either ezetimibe (51.3%), gemfibrozil (41.8%) or fenofibrate (43.8%) to add on to statin therapy if the lipid target was not achieved. A few studies have reported that the combination of statin and gemfibrozil increases the risk of myotoxicity and rhabdomyolysis.23 24 In fact, it was stated in our national lipid guideline as well as in the AHA guideline that the combination of statin and gemfibrozil was discouraged due to its potential to cause rhabdomyolysis.5 15 Therefore, the finding from this study that 41.8% of the respondents used a statin-gemfibrozil combination should cause concern.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study was the large sample size. Based on the sample size calculation, the sample size needed was only 384. However, this study managed to achieve 466 respondents, which should give enough power to its findings. Second, this study involved participants from throughout Malaysia and included physicians working in hospitals, government clinics as well as private general practice, thus providing information of performance across various sectors.

One limitation of this study was the suboptimal response rate. The response rate of 61.4% may not reflect the performance of the non-respondents. This could bring an element of bias to the results of this study. Second, the questionnaire developed for this study used vignettes as one of the ways to assess knowledge. However, clinical vignettes could never be the same as actual real-life practice in which more history as well as physical findings and other information are available.20 Third, the questionnaire only covered certain aspects of lipid management. Other aspects such as management of other types of dyslipidaemia (high triglycerides and low high-density lipoprotein) as well as non-pharmacological management of dyslipidaemia were not covered in this study. Fourth, there was lack of standardisation in the delivery of the questionnaires. Some were delivered by hand while others were delivered online. This may lead to bias in terms of the results of the two groups. However, when the authors analysed the total knowledge score between these two groups, there was no difference in the total knowledge score between them (p=0.09). Finally, as mentioned before, this study was conducted only on postgraduate primary care trainees. Therefore, it may not reflect the performance of other primary care physicians in Malaysia. However, the hypothesis was that this population should perform better than those primary care doctors not currently in training. Based on that hypothesis, we should not expect better results than this for the group of primary care physicians not in training. However, this is just a hypothesis, and further studies are needed to prove it.

Comparison with existing literature

The level of awareness in this study was much higher compared to a study done in China among community physicians, in which the awareness level on their national guideline was very low at 12%.3 This large difference may be due to their study being done on physicians who were not on a postgraduate training programme, unlike in our study. Another reason given by that particular study was that the physicians were unable to access medical information adequately.3 This is different to the situation in our country where medical information, specifically the Malaysian CPG, is widely available and accessible on the internet. Another study done in the USA reported almost a similar finding in which awareness of the national lipid guideline among primary care physicians was very good (>90%).19 Therefore, the awareness level among our postgraduate primary care trainees can be considered to be good.

The knowledge of the respondents in this study is considered satisfactory although it could be better. A study in China again reported that knowledge about management of hypercholesterolaemia among the community physicians was very poor.3 On the other hand, a US study reported that primary care physicians in that country were very knowledgeable about managing dyslipidaemia.11

Several studies have also looked into the practice among primary care physicians in managing dyslipidaemia based on available guidelines. A study in Spain reported that almost all of the physicians followed the guideline in managing dyslipidaemia.25 This study involved not just primary care physicians but also hospital based specialists.25 Another study done in the USA among primary care physicians reported just one third (33%) of the physicians adhered to the guideline in their lipid management practice.1

Implications for future research and clinical practice

Based on the results of this study, it is recommended that improvement in the knowledge as well as practice among postgraduate primary care trainees in managing dyslipidaemia is needed and should be implemented as part of their training programme. One of the ways to achieve this is to optimise adoption of the published guideline into clinical practice. Second, further research to examine the performance of primary care physicians who are not in postgraduate training is highly recommended. Such a study may give additional information about those not in training. Finally, further studies examining the barriers of adoption of the published guideline is also necessary to improve the practice of lipid management.

Conclusion

The outcomes of this study showed the level of awareness and use of lipid guidelines among postgraduate primary care trainees to be high. However, there were still gaps in their knowledge and clinical practice. Further studies are therefore necessary to explore the reason for this. In addition, measures should be taken to emphasise optimal adherence to guidelines in order to improve the management of dyslipidaemia.

Footnotes

Contributors: AHS designed this study, developed the questionnaire, applied for funding, collected the data and did the data analysis. YCC supervised the study, revised and approved the study design and the questionnaire, helped in data collection and revised the data analysis. AHS drafted the manuscript and YCC revised and edited the manuscript. Both authors interpreted the results, revised the report and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was funded by University Malaya RGMS Research (grant project No: PO031-2014B).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University Malaya Medical Centre Ethics Committee.

Participants: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Eaton CB, Galliher JM, McBride PE et al. . Family physician's knowledge, beliefs, and self-reported practice patterns regarding hyperlipidemia: a National Research Network (NRN) survey. J Am Board Fam Med 2006;19:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gowani SA, Shoukat S, Taqui AM et al. . Results of a cross-sectional survey about lipid-management practices among cardiologists in Pakistan: assessment of adherence to published treatment guidelines. Clin Ther 2009;31:1604–14. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan F, Xie J, Wang GL et al. . Community-wide survey of physicians’ knowledge of cholesterol management. Chin Med J 2010;123:884–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marques-Vidal P, Arveiler D, Evans A. Awareness, treatment and control of hyperlipidaemia in middle-aged men in France and northern Ireland in 1991-1993: the PRIME study. Prospective epidemiological study of myocardial infarction. Acta Cardiol 2002;57:117–23. 10.2143/AC.57.2.2005383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health Malaysia Management of dyslipidemia, clinical practice guideline. 4th edn Malaysia: Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan Azman WA, Sim KH. Annual Report of The NCVD-ACS Registry 2009&2010. Malaysia: Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo JY, Ma YT, Yu ZX et al. . Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of dyslipidemia among adults in Northwestern China: the cardiovascular risk survey. Lipids Health Dis 2014;13:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez CJ, Cai J, Swett K et al. . High cholesterol awareness, treatment, and control among Hispanic/Latinos: results from the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4:pii: e001867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verhave JC, Troyanov S, Mongeau F et al. . Prevalence, awareness, and management of CKD and cardiovascular risk factors in publicly funded health care. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;9:713–19. 10.2215/CJN.06550613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chia YC, Lim HM, Ching SM. Does use of pooled cohort risk score overestimate the use of statin?: a retrospective cohort study in a primary care setting. BMC Family Pract 2014;15:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg RJ, Rosen J, Roseli A et al. . Survey of physician's attitudes and practices toward lipid-lowering management strategies. Cardiology 2007;107:302–6. 10.1159/000099066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gil-Guillén V, Hermida E, Pita-Fernandez S et al. . A cardiovascular educational intervention for primary care professionals in Spain: positive impact in a quasi-experimental study. Br J Gen Pract 2015;65:e32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad WMAW, Amin WAAWM, Aleng NA et al. . Some practical guidelines for effective sample-size determination in observational studies. Aceh Int J Sci Technol 2012;1:51–3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook C, Heath F, Thompson RL. A meta analysis of response rates in web or internet based surveys. Educ Psychol Meas 2000;60:821–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults. American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhandari PM, Thapa K, Dhakal S et al. . Breast cancer literacy among higher secondary students: results from a cross-sectional study in Western Nepal. BMC Cancer 2016;16:119 10.1186/s12885-016-2166-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aluko OO, Adebayo AE, Adebisi TF et al. . Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of occupational hazards and safety practices in Nigerian healthcare workers. BMC Res Notes 2016;9:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sudeshna R, Aparajita D. Determinants of menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls: a multivariate analysis. Natl J Community Med 2012;3:294. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosca L, Linfante AH, Benjamin EJ et al. . National study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines. Circulation 2005;111:499–510. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154568.43333.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erhardt LR, Hobbs FDR. A global survey of physicians’ perceptions on cholesterol management: the From The Heart study. Int J Clin Pract 2007;61:1078–85. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01420.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beckett RD, Schepers SM, Gordon SK. Risk of new-onset diabetes associated with statin use. SAGE Open Med 2015;3:2050312115605518 10.1177/2050312115605518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah RV, Goldfine AB. Statins and risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2012;126:e282–4. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.122135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones PH, Davidson MH. Reporting rate of rhabdomyolysis with fenofibrate + statin versus gemfibrozil + any statin. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:120–2. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enger C, Gately R, Ming EE et al. . Pharmacoepidemiology safety study of fibrate and statin concomitant therapy. Am J Cardiol 2010;106:1594–601. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García Mancebo ML, Rubio Tejero AI, Tornel Osorio PL et al. . [Degree of knowledge and control in dyslipidemia among doctors of Murcia Region, Spain (2004-2005)]. Rev Esp Salud Pública 2008;82:423–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]