Abstract

Objectives

Survivors of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake have an increased risk of depressive symptoms. We sought to examine whether participation in group exercise and regular walking could mitigate the worsening of depressive symptoms among older survivors.

Design

Prospective observational study.

Setting

Our baseline survey was conducted in August 2010, ∼7 months prior to the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami, among people aged 65 or older residing in Iwanuma City, Japan, which suffered significant damage in the disaster. A 3-year follow-up survey was conducted in 2013.

Participants

3567 older survivors responded to the questionnaires predisaster and postdisaster.

Primary outcome measures

Change in depressive symptoms was assessed using the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).

Results

From predisaster to postdisaster, the mean change in GDS score increased by 0.1 point (95% CI −0.003 to 0.207). During the same interval, the frequency of group exercise participation and daily walking time also increased by 1.9 days/year and 1.3 min/day, respectively. After adjusting for all covariates, including personal experiences of disaster, we found that increases in the frequency of group exercise participation (B=−0.139, β=−0.049, p=0.003) and daily walking time (B=−0.087, β=−0.034, p=0.054) were associated with lower GDS scores. Interactions between housing damage and changes in group exercise participation (B=0.103, β=0.034, p=0.063) and changes in walking habit (B=0.095, β=0.033, p=0.070) were marginally significant, meaning that the protective effects tended to be attenuated among survivors reporting more extensive housing damage.

Conclusions

Participation in group exercises or regular walking may mitigate the worsening of depressive symptoms among older survivors who have experienced natural disaster.

Keywords: older adults, natural disaster, geriatric depression scale, the JAGES project, multiple imputation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strength of this study is the unprecedented and fortuitous availability of information predating the disaster.

The study design enabled us to effectively address the problem of recall bias that occurs in most studies conducted in postdisaster settings.

Selection bias might have occurred because of the 59% response rate to the baseline survey.

The measurements rely entirely on self-reported data.

Introduction

The frequency of natural disasters such as hurricanes, floods and earthquakes has been increasing worldwide.1 The experience of disaster presents a significant burden on the mental health of survivors.2–4 Depression in older adults is strongly associated with being house-bound,5 which may lead to a decline in physical and cognitive function and eventually to premature death.6 To clarify the factors that contribute to mental health recovery after a disaster, several postdisaster surveys have been previously conducted.7–9 However, these studies have relied on survivors' recollection of their predisaster mental health status, potentially contributing to recall bias, that is, the experience of disaster can colour the respondents' assessment of their status ex ante. Clearly, it would be desirable to have predisaster information on survivors in order to avoid information bias.10 To the best of our knowledge, only two studies examining mental health status prior to disaster events have been conducted.11 12 Both studies suggested that major disaster was associated with an increase in the risk for common mental health disorders independently of previous mental health status and other potentially confounding factors. Furthermore, a previous study suggested that dwelling house damage caused by major disasters was associated with worsening depressive symptoms in older survivors.13 Little evidence, however, is available for the prevention of mental health problems from a public health intervention perspective.

Physical activity, which is a modifiable behaviour, has the benefit of preventing or alleviating depressive symptoms14 15 and of treating depression16 17 in older adults. It has also been found that regular walking is by far the most prevalent physical activity in older adults18 and has protective effects for depression.19 20 Participation in group exercises may be particularly effective for mental health promotion in the elderly by enhancing social participation in addition to physical activity.21 22 However, it is unclear whether the same benefits can be also obtained following the experience of natural disaster.

Following the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011, various health promotion interventions—including group exercise programmes for older adults—were initiated in disaster-stricken areas to address the health needs of survivors.23 24 Tomata and colleagues24 reported that there was no significant psychological benefit from attending group exercises once a month among middle-aged and older survivors in disaster-stricken areas. Possible reasons for this null finding were insufficient exercise frequency and sampling bias24 as participants might have had good health, behaviour and awareness before the disaster and might not have suffered much damage as a result of the disaster.

The purpose of the present study was to examine whether participation in group exercise and regular walking could mitigate the worsening of depressive symptoms among older survivors of the Great East Japan Earthquake after taking into account predisaster mental health status. We hypothesised that participation in group exercises or regular walking may mitigate the worsening of depressive symptoms among older survivors who have experienced natural disaster. These associations, however, may differ according to the extent of damage caused by the disaster.

Methods

Study design

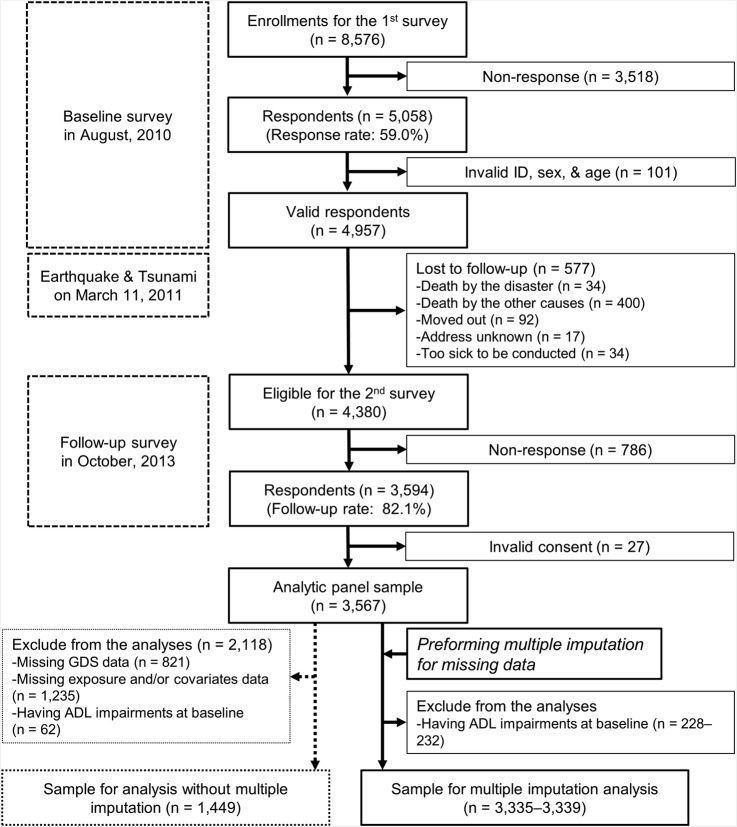

Our longitudinal study was conducted in Iwanuma City, a coastal municipality in the Miyagi prefecture, Japan, located ∼80 km west of the epicentre of the Great East Japan Earthquake that occurred on 11 March, 2011. Iwanuma City (total population 44 000) suffered tremendous damage from the earthquake and tsunami: 180 people were killed,25 and 48% (29 km2) of the land was inundated by seawater.26 Our study takes advantage of the coincidence that Iwanuma City happened to be one of the field sites of the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES) Project,27 28 a nationwide, ongoing prospective cohort study that started in 2010 to investigate the social and behavioural factors associated with healthy ageing. As part of the baseline survey for the JAGES project cohort, we conducted a census of all adults aged 65 years or older living in Iwanuma City in August 2010, 7 months prior to the earthquake. A 3-year follow-up survey was conducted in November 2013, 2 years and 7 months after the earthquake. After sending the questionnaires to all older adults living in Iwanuma City in the follow-up survey, we visited all the residences to collect the completed questionnaires. The participant flow chart is shown in figure 1.29

Figure 1.

Participants flow in the Iwanuma project and in the present study for with and without multiple imputation analysis.

Study participants were selected for the Iwanuma project based on the following inclusion criteria: respondents from the 2010 and 2013 surveys who had no limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) (ie, they could independently walk, bathe and visit the toilet) at the baseline survey in 2010.

All participants gave informed consent.

Measurements

Change in depressive symptoms

We assessed depressive symptoms using the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)30 31 as a continuous variable in 2010 and 2013. The score range is 0–15 and higher value means greater severity of depressive symptoms. Change in depressive symptoms calculated by subtracting the score in 2010 from that in 2013.

Changes in group exercise participation and regular daily walking

In predisaster and postdisaster surveys, we ascertained the frequency of group exercise participation (4 days/week or more, 2–3 days/week, once a week, 1–3 time(s)/month, a few times/year or none), as well as regular daily walking behaviour (<30, 30–59, 60–89 or 90 min/day or more). We converted those categories into continuous variables, 260, 130, 52, 24, 6 and 0 day(s)/year, respectively, for group exercise participation, and 15, 45, 75 and 105 min/day, respectively, for walking behaviour. Changes in group exercise participation and regular daily walking were calculated by subtracting the frequency and the time measured in 2010 from those measured in 2013.

Covariates

Information on age and sex were derived from the public register. Psychological disorder, comorbid disease status other than psychological disorder (no disease vs one or more diseases) and educational attainment were self-reported at baseline. Changes in drinking habits, smoking and job status before and after the disaster and impaired ADL after the disaster were categorised according to the 2010 and 2013 surveys. Change in instrumental ADL (IADL) was calculated by subtracting the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology Index of Competence (TMIG-IC)32 score in 2010 from that in 2013. A lower value indicated a worsening ability to perform IADL. As an index of the personal experience of disaster damage, we asked about housing damage (1 no damage, 2 some damage, 3 partial destruction, 4 almost destroyed or 5 complete destruction), as well as the death of family member(s), while changes in income were calculated by subtracting the figure reported in 2010 from that in 2013.

Statistical analyses

Because 2061 (57.8%) respondents in the analytic panel sample (n=3567) had missing data for one or more items in the 2010 and/or 2013 surveys, we performed multiple imputation. We created 20 multiple imputed data sets which included all measurement variables using a multivariate normal imputation method under a missing at random assumption, and combined the estimated parameters using Rubin's combination methods.33 34

We compared the respondents' characteristics between complete cases without ADL impairments at baseline (n=1449) versus those who had missing data and/or had ADL impairments at baseline (n=2118). Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to investigate the relationship of exposure with change in depressive symptoms. Multiple linear regression models were used to examine the association of change in group exercise participation/regular walking before and after the disaster with change in depressive symptoms. The following four models were constructed. Changes in frequency of group exercise participation and changes in daily walking time were converted into Z-scores and were included in crude model. In model 1, sex and age were added to crude model. In model 2, we added three sets of covariates: (1) covariates evaluated only at baseline (disease status and educational attainment), (2) covariates measured in the 2010 and the 2013 surveys (impaired ADL, changes in drinking habits and smoking habits, job status, equivalent income and IADL score) and (3) covariates ascertained just on the 2013 survey (housing damage and death of family members). Model 3 added interaction terms: change in group exercise participation × housing damage and change in walking habit × housing damage. These models were also constructed in participants with GDS score <5 (non-depressed) or ≥5 (depressed)35 separately. We used STATA 13/SE (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) for all statistical analyses and multiple imputations with the statistical significance set at p<0.05 and the marginal significance set at p<0.10.

Results

Table 1 shows the respondents' characteristics for the complete case sample as well as the sample missing data and/or had ADL impairments at baseline. Although there were significant differences in two groups with respect to mean GDS, frequency of group exercise participation and daily walking time, there were no significant differences between the groups in the changes in those variables. Participants who had missing data and/or had ADL impairments at baseline tended to be older, more likely to be female, with a higher prevalence of comorbidity and lower educational attainment and IADL score.

Table 1.

Participants' characteristics and comparison between participants with and without missing data and/or activities of daily living impairments at baseline

| Total (n=3567) |

Complete cases without ADL impairments at baseline (n=1449) |

Participants who had missing data and/or had ADL impairments at baseline (n=2118) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of valid responses |

Mean/n | SD/% | Mean/n | SD/% | Number of valid responses | Mean/n | SD/% | p Value | |

| Geriatric Depression Scale, score | |||||||||

| Baseline | 3074 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 1625 | 4.1 | 3.6 | <0.001 |

| Change | 2746 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 1297 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 0.407 |

| Frequency of group exercise participation, day(s)/year | |||||||||

| Baseline | 2992 | 20.4 | 44.1 | 24.3 | 47.6 | 1543 | 16.9 | 40.2 | <0.001 |

| Change | 2887 | 1.9 | 44.5 | 3.0 | 46.4 | 1438 | 0.8 | 42.4 | 0.203 |

| Walking habit, min/day | |||||||||

| Baseline | 3395 | 45.7 | 30.5 | 49.7 | 30.5 | 1946 | 42.7 | 30.2 | <0.001 |

| Change | 3351 | 1.3 | 30.7 | 1.9 | 30.1 | 1902 | 0.8 | 31.1 | 0.337 |

| Age, year | 3567 | 73.6 | 6.3 | 71.7 | 5.5 | 2118 | 75.0 | 6.4 | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 3567 | 2015 | 56.5% | 622 | 42.9% | 2118 | 1393 | 65.8% | <0.001 |

| Psychological disorder, n (%) | 3479 | 44 | 1.3% | 8 | 0.6% | 2030 | 36 | 1.8% | 0.001 |

| One or more disease(s)*, n (%) | 3479 | 2731 | 78.5% | 1078 | 74.4% | 2030 | 1653 | 81.4% | <0.001 |

| Educational attainment, year | 3429 | 11.5 | 2.3 | 12.1 | 2.2 | 1980 | 11.1 | 2.3 | <0.001 |

| Activities of daily living, n (%) | 3443 | 1994 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Maintain | 3039 | 88.3% | 1394 | 96.2% | 1645 | 82.5% | |||

| Impaired after the earthquake | 265 | 7.7% | 55 | 3.8% | 210 | 10.5% | |||

| Disabled at baseline | 139 | 4.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 139 | 7.0% | |||

| Change in drinking habit, n (%) | 3466 | 2017 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Drink.→drink. | 1031 | 29.7% | 580 | 40.0% | 451 | 22.4% | |||

| Non→drink. | 74 | 2.1% | 33 | 2.3% | 41 | 2.0% | |||

| Drink.→non | 240 | 6.9% | 122 | 8.4% | 118 | 5.9% | |||

| Non→non | 2121 | 61.2% | 714 | 49.3% | 1407 | 69.8% | |||

| Change in smoking habit, n (%) | 3252 | 1803 | 0.203 | ||||||

| Non→non | 2869 | 88.2% | 1261 | 87.0% | 1608 | 89.2% | |||

| Smok.→non | 115 | 3.5% | 55 | 3.8% | 60 | 3.3% | |||

| Non→smok. | 18 | 0.6% | 7 | 0.5% | 11 | 0.6% | |||

| Smok.→smok. | 250 | 7.7% | 126 | 8.7% | 124 | 6.9% | |||

| Change in job status, n (%) | 3057 | 1608 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Working→working | 323 | 10.6% | 196 | 13.5% | 127 | 7.9% | |||

| No→working | 89 | 2.9% | 40 | 2.8% | 49 | 3.0% | |||

| Working→no | 225 | 7.4% | 118 | 8.1% | 107 | 6.7% | |||

| No→no | 2420 | 79.2% | 1095 | 75.6% | 1325 | 82.4% | |||

| Dwelling house damage, n (%) | 3466 | 2017 | <0.001 | ||||||

| No damage | 1423 | 41.1% | 627 | 43.3% | 796 | 39.5% | |||

| Some damage | 1496 | 43.2% | 640 | 44.2% | 856 | 42.4% | |||

| Partial destruction | 257 | 7.4% | 93 | 6.4% | 164 | 8.1% | |||

| Almost destruction | 131 | 3.8% | 42 | 2.9% | 89 | 4.4% | |||

| Complete destruction | 159 | 4.6% | 47 | 3.2% | 112 | 5.6% | |||

| Lost family member(s), n (%) | 3567 | 936 | 26.2% | 370 | 25.5% | 2065 | 566 | 27.4% | 0.428 |

| Equivalent income, ten thousand yen | |||||||||

| Baseline | 2911 | 230.2 | 141.8 | 246.5 | 136.7 | 1462 | 214.0 | 145.0 | <0.001 |

| Change | 2561 | −10.4 | 122.8 | −8.6 | 117.4 | 1112 | −12.6 | 129.6 | 0.413 |

| IADL scale, score | |||||||||

| Baseline | 3336 | 11.6 | 2.3 | 12.1 | 1.6 | 1887 | 11.3 | 2.7 | <0.001 |

| Change | 3180 | −0.6 | 2.0 | −0.4 | 1.6 | 1731 | −0.8 | 2.2 | <0.001 |

*other than psychological disorder.

ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; SD, standard deviation.

Online supplementary table S1 shows the relationship of change in depressive symptoms with exposure and covariates in the complete case sample without ADL impairments at baseline. Based on correlation analyses, more frequent participation in group exercise was associated with lower depressive symptoms. Participants who had ADL impairments, who changed their smoking habits or suffered extensive housing damage, were more vulnerable to developing depressive symptoms.

bmjopen-2016-013706supp_table1.pdf (18.6KB, pdf)

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the multiple linear regression models based on the multiply imputed data sets. Significant and marginally significant predictors of lower depressive symptoms included increases in the frequency of group exercise participation (B=−0.139, β=−0.049, p=0.003) and daily walking time (B=−0.087, β=−0.034, p=0.054), after adjusting for all covariates, respectively. In the model incorporating interaction terms, the group exercise participation × housing damage interaction (B=0.103, β=0.034, p=0.063) and the change in walking habit × housing damage interaction (B=0.095, β=0.033, p=0.070) were marginally significant, meaning that the protective effects of group exercise participation and walking tended to be attenuated among survivors reporting more extensive housing damage. Results of all regression models based on the complete data set are shown in online supplementary table S2. These relationships were attenuated when using the complete case analysis. Online supplementary table S3 shows the results of the multiple linear regression models with (GDS≥5) and without (GDS<5) depressive symptoms at baseline. Large coefficients were generally observed in older adults with depressive symptoms compared with those without depressive symptoms at baseline, although these associations did not reach statistical significance after adjustment of covariates because of limited statistical power.

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression of changes in group exercise participation and walking habit (converted into Z-scores) with change in depressive symptoms by analysing multiply imputed data sets (n=3335–3339, crude model and model 1)

| Crude model |

Model 1 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | β | t | p Value | B | 95% CI | β | t | p Value | ||

|

Change in group exercise participation (44.5 days/year) |

−0.188 | −0.290 to −0.086 | −0.061 | −3.63 | <0.001 | −0.169 | −0.270 to −0.068 | −0.055 | −3.30 | 0.001 | |

|

Change in walking habit (30.7 mins/day) |

−0.199 | −0.305 to −0.094 | −0.068 | −3.72 | <0.001 | −0.192 | −0.296 to −0.087 | −0.066 | −3.60 | <0.001 | |

| Age (year) | 0.034 | 0.017 to 0.050 | 0.073 | 3.97 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Sex (1 men, 2 women) | −0.133 | −0.328 to 0.062 | −0.023 | −1.33 | 0.183 | ||||||

CI, confidence interval.

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression of changes in group exercise participation and walking habit (converted into Z-scores) with change in depressive symptoms by analysing multiply imputed data sets (n=3335–3339, models 2 and 3)

| Model 2 |

Model 3 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | β | t | p Value | B | 95% CI | β | t | p Value | ||

|

Change in group exercise participation (44.5 days/year) |

−0.156 | −0.256 to −0.057 | −0.051 | −3.07 | 0.002 | −0.139 | −0.239 to −0.038 | −0.049 | −3.00 | 0.003 | |

|

Change in walking habit (30.7 mins/day) |

−0.098 | −0.199 to 0.003 | −0.034 | −1.90 | 0.058 | −0.087 | −0.189 to 0.016 | −0.034 | −1.93 | 0.054 | |

| Age (year) | 0.006 | −0.013 to 0.024 | 0.012 | 0.59 | 0.558 | 0.005 | −0.013 to 0.024 | 0.011 | 0.55 | 0.585 | |

| Sex (1 men, 2 women) | −0.119 | −0.364 to 0.126 | −0.020 | −0.95 | 0.341 | −0.119 | −0.364 to 0.125 | −0.020 | −0.96 | 0.339 | |

| Psychological disorder (0 no, 1 yes) | −0.769 | −2.194 to 0.655 | −0.029 | −1.06 | 0.290 | −0.774 | −2.199 to 0.651 | −0.029 | −1.06 | 0.287 | |

| Disease status (0 no, 1 one or more)* | −0.203 | −0.426 to 0.019 | −0.029 | −1.79 | 0.074 | −0.207 | −0.430 to 0.016 | −0.029 | −1.82 | 0.069 | |

| Educational attainment (year) | 0.053 | 0.007 to 0.098 | 0.042 | 2.28 | 0.022 | 0.053 | 0.008 to 0.098 | 0.043 | 2.31 | 0.021 | |

| Impaired ADL (0 no, 1 impaired) | 0.568 | 0.025 to 1.110 | 2.950 | 2.05 | 0.040 | 0.584 | 0.041 to 1.126 | 3.032 | 2.11 | 0.035 | |

| Changes in drinking habits | |||||||||||

| Non→drink. | −0.563 | −1.236 to 0.111 | −0.029 | −1.64 | 0.101 | −0.570 | −1.238 to 0.098 | −0.029 | −1.67 | 0.095 | |

| Drink.→non | 0.213 | −0.221 to 0.646 | 0.018 | 0.96 | 0.336 | 0.203 | −0.229 to 0.635 | 0.018 | 0.92 | 0.357 | |

| Non→non | −0.028 | −0.281 to 0.225 | −0.005 | −0.22 | 0.827 | −0.034 | −0.286 to 0.219 | −0.006 | −0.26 | 0.793 | |

| Changes in smoking habits | |||||||||||

| Smoke.→non | 0.841 | 0.285 to 1.396 | 0.051 | 2.97 | 0.003 | 0.826 | 0.274 to 1.378 | 0.050 | 2.93 | 0.003 | |

| Non→smoke. | 1.308 | −0.185 to 2.801 | 0.035 | 1.72 | 0.086 | 1.267 | −0.227 to 2.762 | 0.034 | 1.66 | 0.097 | |

| Smoke.→smoke. | −0.308 | −0.667 to 0.051 | −0.027 | −1.68 | 0.093 | −0.304 | −0.661 to 0.054 | −0.027 | −1.67 | 0.096 | |

| Changes in job status | |||||||||||

| No→working | 0.284 | −0.422 to 0.990 | 0.017 | 0.79 | 0.429 | 0.297 | −0.403 to 0.997 | 0.018 | 0.83 | 0.405 | |

| Working→no | 0.624 | 0.171 to 1.078 | 0.056 | 2.70 | 0.007 | 0.630 | 0.176 to 1.083 | 0.057 | 2.72 | 0.007 | |

| No→no | 0.270 | −0.027 to 0.566 | 0.037 | 1.79 | 0.074 | 0.274 | −0.023 to 0.570 | 0.038 | 1.81 | 0.071 | |

|

Dwelling house damage (1 no damage→5 complete destruction) |

0.212 | 0.105 to 0.319 | 0.074 | 3.90 | <0.001 | 0.215 | 0.108 to 0.321 | 0.075 | 3.96 | <0.001 | |

| Death of family member(s) (0 no, 1 yes) | 0.118 | −0.104 to 0.340 | 0.018 | 1.04 | 0.299 | 0.128 | −0.095 to 0.350 | 0.019 | 1.13 | 0.260 | |

| Change in equivalent income (million yen) | −0.059 | −0.145 to 0.027 | −0.026 | −1.36 | 0.176 | −0.059 | −0.144 to 0.027 | −0.025 | −1.35 | 0.179 | |

| Change in IADL (score) | −0.266 | −0.337 to −0.195 | −0.192 | −7.33 | <0.001 | −0.267 | −0.338 to −0.196 | −0.193 | −7.37 | <0.001 | |

| Interaction | |||||||||||

| Change in exercise x house damage | 0.103 | −0.006 to 0.213 | 0.034 | 1.86 | 0.063 | ||||||

| Change in walking time x house damage | 0.095 | −0.008 to 0.198 | 0.033 | 1.81 | 0.070 | ||||||

*other than psychological disorder.

ADL, activities of daily living; CI, confidence interval; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

bmjopen-2016-013706supp_table2.pdf (28KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013706supp_table3.pdf (18.2KB, pdf)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the potential benefits of group exercise participation and regular walking on depressive symptoms following exposure to natural disaster in which information on mental health status was available predating the event. We found evidence that group exercise participation and regular walking after a natural disaster may reduce the risk of depressive symptoms in older survivors and after adjusting for level of damage, including the death of a family member and the extent of destruction of their homes. However, these preventive effects tended to be attenuated among survivors who reported suffering more extensive damage to their homes from the earthquake and tsunami.

Although the mean change in the GDS score before and after the disaster was only +0.1 among all study participants, 15.3% of those without depressive symptoms (GDS<5) at the time of the baseline survey (n=1833) developed mild or more severe depressive symptoms (GDS≥5) after the disaster (data not shown). This rate was higher compared with that of a previous study (11.8%)27 on 37 193 community-dwelling older adults sampled from 24 municipalities in Japan, most of whom had not been directly affected by the disaster, with the same period, follow-up duration and depressive symptom criteria as those in the present study. Consistent with previous research,2 we confirmed that the disaster may have had an adverse impact on the psychological status of older adults living in disaster-stricken areas.

Group exercise participation has positive physical activity and social participation effects on mental health.21 Systematic reviews have shown that physical activity has preventive and treatment effects on depression and alleviates depressive symptoms in older adults.14–17 36 Furthermore, a group exercise review for adults and older adults indicated that participating in group exercise promotes mental health by inducing enjoyment, enhancing self-esteem and buffering stress.21 These positive feelings are significantly connected with and can lead to a reduction in depressive symptoms with a small to moderate effect size.37 38 Another possible mediator between group exercise participation and depression prevention is receiving social support.21 22 In the present study, we did not find any significant relationship between social support and depressive symptoms, although we investigated models that included instrumental and emotional social support from friends or acquaintances before and after disasters (data was not shown). From these results, we can conclude that group exercise participation can relieve depressive feelings in older survivors, even in the unusual situation following a natural disaster.

We found marginally significant links between increasing in regular walking habits and alleviation of depressive symptoms in the present study. These results were consistent with previous observational studies under usual conditions; that is, not after a disaster.19 39 A 10-year prospective cohort study revealed that older women who walk for more than 40 min/day have a lower risk of major depressive disorders, and also showed a dose–response relationship between daily walking time and risk.19 However, the relationship was weak for walking at an easy pace (<2 miles/hour) and more significant for an average or more brisk pace (≥2 miles/hour).19 Several randomised controlled trials indicated that group walking at a brisk pace can relief depressive symptoms in older adults.20 40 41 Walking may also be recommended to prevent depressive symptoms in groups. The fact that we could not investigate pace, intensity or manner (individually or in a group) in the present study was a major limitation.

Further, it is worth noting that these preventive effects on depressive symptoms may be present even if the extent of damage from the disaster (housing damage or death of a family member) is taken into account. To mitigate the worsening of depressive symptoms resulting from each level of housing damage (B=0.215, see table 3), participating in an exercise group ∼5–6 times/month—or daily walking of 75 mins/day—was required. In addition, an increasing frequency of participating in an exercise group once a week (=52 days/year) was equivalent to +2.75 million yen (≈27.5 thousand dollars) of change in equivalent income, although this was not a statistically significant relevant factor. On the basis of the standardised β coefficients, the mitigational impact of change in group exercise participation (β=−0.049) was comparable with the worsening impact of low educational attainment (β=0.043), the interruption of smoking (β=0.050) and the loss or interruption of a job (β=0.057). However, we also found marginally significant interactions between changes in group exercise participation, walking habits and home damage, indicating that the protective effects of exercise tended to be attenuated among survivors reporting more extensive housing damage. Although the reason for this result remains a matter of speculation, survivors who suffered extensive housing damage may have had to walk involuntarily rather than engaging in physical activity for leisure. These results suggest that substantial support (eg, providing an attractive group walking programme with longer duration and higher frequency) might be needed for survivors who lived in areas severely damaged by a disaster to bring the benefits of group exercise participation and regular walking.

The strength of the present study is the unprecedented and fortuitous availability of information predating the disaster. However, several limitations need to be mentioned. First, the measurements used in our analysis relied entirely on self-reported data. Therefore, depressed subjects may recall their exercise differently from non-depressed subjects (information bias); in other words, depressed people may have under-reported their physical activity. Furthermore, our use of GDS may have led to an underestimation of the impacts of group exercise participation and walking because the GDS omits neurovegetative symptoms (for which physical activity may be particularly effective). Second, physical activity was not assessed using a standardised questionnaire which is widely used and associated with sufficient validity and reliability. Furthermore, the type and intensity of the group exercises in which participants took part was not investigated. Therefore, we could not distinguish the causes of the positive relationship between group exercise participation and the prevention of depressive symptoms between physical activity itself and group participation. Self-paced intensity may increase the pleasure people experience when exercising, thereby improving adherence.42 In a future study, we aim to objectively evaluate pace, intensity, style and manner of physical activity to investigate the effects of physical activity on mental health in older adults in a more precise manner, including dose–response relationships. Third, excluding older adults who had ADL impairments at baseline from the present analyses may have led to the under-representation of those with physical illnesses and associated depressive symptoms. Fourthly, and most importantly, we cannot exclude the possibility of simultaneous changes in exercise patterns and depressive symptoms happening during the course of follow-up. Thus, even though our analyses looked at changes in exercise predicting changes in depressive symptoms (first differences analysis), we cannot exclude the possibility that people stopped exercising because they felt depressed, or that they started to exercise because they felt well.

We conclude that increases in frequency of participating in group exercises and daily walking time after a natural disaster may alleviate depressive symptoms after a disaster in older survivors. These effects could be expected even after adjusting for the suffering resulting from serious damage, such as the death of a family member or the destruction of the primary residence. Giving older survivors the opportunity and environment for group exercise participation and walking in areas affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake and in future serious natural disasters could be an effective support mechanism for prevention of depressive symptoms.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support and cooperation of the Iwanuma mayor's office, and the staff of the Health and Welfare of Iwanuma City government. This study used data from the JAGES project as one of their research projects.

Footnotes

Contributors: TT conceived, designed, analysed and interpreted the data and wrote the article; YS, YM and YS conceived, designed and critically revised the article; JA conceived, designed, collected the data and critically revised the article; KK conceived, designed and critically revised the article and is principal investigator for the JAGES project and IK conceived, designed and critically revised the article and is a principal investigator for the Iwanuma project.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health, National Institute on Ageing (research grant number 1R01AG042463-01A1), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (No. 22592327, 22390400, 23243070, 24390469) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and Health Labor Sciences Research Grant (No. 24140701) from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

Disclaimer: The funding sources had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee at the Graduate school of Medicine, Chiba University, approved the study protocol.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. EM-DAT: The International Disaster Database. Secondary EM-DAT: The International Disaster Database. 2014. http://www.emdat.be/

- 2.Matsubara C, Murakami H, Imai K et al. Prevalence and risk factors for depressive reaction among resident survivors after the tsunami following the Great East Japan Earthquake, March 11, 2011. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e109240 10.1371/journal.pone.0109240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yokoyama Y, Otsuka K, Kawakami N et al. Mental health and related factors after the Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e102497 10.1371/journal.pone.0102497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki Y, Tsutsumi A, Fukasawa M et al. Prevalence of mental disorders and suicidal thoughts among community-dwelling elderly adults 3 years after the niigata-chuetsu earthquake. J Epidemiol 2011;21:144–50. 10.2188/jea.JE20100093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi NG, McDougall GJ. Comparison of depressive symptoms between homebound older adults and ambulatory older adults. Aging Ment Health 2007;11:310–22. 10.1080/13607860600844614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiske A, Wetherell JL, Gatz M. Depression in older adults. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2009;5:363–89. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali M, Farooq N, Bhatti MA et al. Assessment of prevalence and determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of earthquake in Pakistan using Davidson Trauma Scale. J Affect Disord 2012;136:238–43. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaudoin CE. News, social capital and health in the context of Katrina. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2007;18:418–30. 10.1353/hpu.2007.0024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wind TR, Komproe IH. The mechanisms that associate community social capital with post-disaster mental health: a multilevel model. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:1715–20. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buttenheim A. Impact evaluation in the post-disaster setting: a case study of the 2005 Pakistan earthquake. J Dev Effect 2010;2:197–227. 10.1080/19439342.2010.487942 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Boden JM et al. Impact of a major disaster on the mental health of a well-studied cohort. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:1025–31. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnberg FK, Gudmundsdóttir R, Butwicka A et al. Psychiatric disorders and suicide attempts in Swedish survivors of the 2004 Southeast Asia tsunami: a 5 year matched cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2015;2:817–24. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00124-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuboya T, Aida J, Hikichi H et al. Predictors of depressive symptoms following the Great East Japan earthquake: a prospective study. Soc Sci Med 2016;161:47–54. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blake H, Mo P, Malik S et al. How effective are physical activity interventions for alleviating depressive symptoms in older people? A systematic review. Clin Rehabil 2009;23:873–87. 10.1177/0269215509337449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bridle C, Spanjers K, Patel S et al. Effect of exercise on depression severity in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry 2012;201:180–5. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Richards J et al. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. J Psychiatr Res 2016;77:42–51. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S et al. Exercise for depression in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials adjusting for publication bias. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 2016;38: 247–54. 10.1590/1516-4446-2016-1915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yusuf HR, Croft JB, Giles WH et al. Leisure-time physical activity among older adults. United States, 1990. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:1321–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lucas M, Mekary R, Pan A et al. Relation between clinical depression risk and physical activity and time spent watching television in older women: a 10-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:1017–27. 10.1093/aje/kwr218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernard P, Ninot G, Bernard PL et al. Effects of a six-month walking intervention on depression in inactive post-menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Aging Ment Health 2015;19:485–92. 10.1080/13607863.2014.948806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanamori S, Takamiya T, Inoue S. Group exercise for adults and elderly: determinants of participation in group exercise and its associations with health outcome. J Phys Fitness Sports Med 2015;4:315–20. 10.7600/jpfsm.4.315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Street G, James R, Cutt H. The relationship between organised physical recreation and mental health. Health Promot J Austr 2007;18:236–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Japan Health Promotion Fitness Foundation. Survey research on physical/psychological support activities through exercise and sports and their utilization method in affected areas of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Health Promotion Fitness Foundation, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomata Y, Sato N, Kogure M et al. Health effects of interventions to promote physical activity in survivors of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. A longitudinal study. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2015;62:66–72. 10.11236/jph.62.2_66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishigaki A, Higashi H, Sakamoto T et al. The Great East-Japan Earthquake and devastating tsunami: an update and lessons from the past Great Earthquakes in Japan since 1923. Tohoku J Exp Med 2013;229:287–99. 10.1620/tjem.229.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. Area of wetted surface from Tsunami disaster, 2011.

- 27.Tani Y, Sasaki Y, Haseda M et al. Eating alone and depression in older men and women by cohabitation status: the JAGES longitudinal survey. Age Ageing 2015;44:1019–26. 10.1093/ageing/afv145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koyama S, Aida J, Kawachi I et al. Social support improves mental health among the victims relocated to temporary housing following the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Tohoku J Exp Med 2014;234:241–7. 10.1620/tjem.234.241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hikichi H, Aida J, Tsuboya T et al. Can community social cohesion prevent PTSD in the aftermath of disaster? A natural experiment from the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. Am J Epidemiol 2016;183:902–10. 10.1093/aje/kwv335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wada T, Ishine M, Kita T et al. Depression screening of elderly community-dwelling Japanese. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1328–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burke WJ, Roccaforte WH, Wengel SP. The short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale: a comparison with the 30-item form. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1991;4:173–8. 10.1177/089198879100400310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koyano W, Shibata H, Nakazato K et al. Measurement of competence: reliability and validity of the TMIG Index of Competence. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 1991;13:103–16. 10.1016/0167-4943(91)90053-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carpenter JR, Kenward MG. Multiple imputation and its application. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schreiner AS, Hayakawa H, Morimoto T et al. Screening for late life depression: cut-off scores for the Geriatric depression scale and the Cornell scale for depression in Dementia among Japanese subjects. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;18:498–505. 10.1002/gps.880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mammen G, Faulkner G. Physical activity and the prevention of depression: a systematic review of prospective studies. Am J Prev Med 2013;45:649–57. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ et al. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 2013;13:119 10.1186/1471-2458-13-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Proyer RT, Gander F, Wellenzohn S et al. Positive psychology interventions in people aged 50–79 years: long-term effects of placebo-controlled online interventions on well-being and depression. Aging Ment Health 2014;18:997–1005. 10.1080/13607863.2014.899978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Julien D, Gauvin L, Richard L et al. The role of social participation and walking in depression among older adults: results from the VoisiNuAge study. Can J Aging 2013;32:1–12. 10.1017/S071498081300007X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gusi N, Reyes MC, Gonzalez-Guerrero JL et al. Cost-utility of a walking programme for moderately depressed, obese, or overweight elderly women in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2008;8:231 10.1186/1471-2458-8-231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robertson R, Robertson A, Jepson R et al. Walking for depression or depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ment Health Phys Act 2012;5:66–75. 10.1016/j.mhpa.2012.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ekkekakis P, Parfitt G, Petruzzello SJ. The pleasure and displeasure people feel when they exercise at different intensities: decennial update and progress towards a tripartite rationale for exercise intensity prescription. Sports Med 2011;41:641–71. 10.2165/11590680-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013706supp_table1.pdf (18.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013706supp_table2.pdf (28KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013706supp_table3.pdf (18.2KB, pdf)