Abstract

Objectives

To assess 2-year durability of joint contracture correction following collagenase injections for Dupuytren's disease.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Orthopaedic Department in Sweden.

Participants

Patients with palpable Dupuytren's cord and active extension deficit (AED) ≥30° in the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and/or proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint. A surgeon injected 0.80 mg collagenase into multiple cord parts and performed finger manipulation under local anaesthesia after 24–48 hours. A hand therapist measured joint contracture before and 5 weeks after injection in all treated patients. Of 57 consecutive patients (59 hands), 48 patients (50 hands) were examined by a hand therapist 24–35 months (mean 26) after injection. Five of the patients had received a second injection in the same finger within 6 months of the first injection.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome was proportion of treated joints with ≥20° worsening in AED from 5 weeks to 2 years.

Results

Between the 5-week and the 2-year measurements, AED had worsened by ≥20° in seven MCP and seven PIP joints (28% of the treated hands; all had received a single injection). Mean AED for the MCP joints was 54° before injection, 6° at 5 weeks and 9° at 2 years and for the PIP joints 30°, 13° and 16°, respectively. For joints with ≥10° contracture at baseline, mean (95 % CI) baseline to 2 years AED improvement was for MCP 49° (41–54) and for PIP 25° (17–32). No treatment-related adverse events were observed at the 2-year follow-up evaluation.

Conclusions

Two years after collagenase injections for Dupuytren's disease, improvement was maintained in 72% of the treated hands. Complete contracture correction was seen in more than 80% of the MCP but in less than half of the PIP joints.

Keywords: Dupuytren, Collagenase

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Indications for collagenase treatment similar to those conventionally used for surgery.

Measurements of joint contracture outcomes at baseline and follow-up independent of the treating surgeon.

Use of an upper-extremity specific measure of patient-reported activity limitations (QuickDASH) and evaluation of patient satisfaction.

High participation rate with 2-year outcomes data available for 95% of the treated hands.

Limitations include a single centre, moderate sample size, lack of 12-month follow-up, QuickDASH administered to only a subgroup of patients at baseline, QuickDASH not validated specifically in patients with Dupuytren's disease, and use of binary patient satisfaction item.

Introduction

Collagenase injection is a non-surgical treatment for patients with Dupuytren's disease causing finger joint contractures.1 2 Treatment comprises injection of collagenase into the cord followed, after about 24–48 hours, by finger manipulation (extension). In the initial multicentre randomised trial by Hurst et al,1 surgeons performed finger manipulation without anaesthesia. Finger manipulation is usually painful and lack of anaesthesia may hamper contracture reduction. In addition, contractures of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint were treated separately with repeated injections given with at least 1-month interval. These procedures have been modified; use of anaesthesia prior to finger manipulation is now standard and treating both joints in one session is common.3 We have used a modified method, injecting a higher collagenase dose (0.80 mg) into multiple parts of the cord and shown good short-term (5 weeks) contracture correction.4 5 With this method, fingers with contracture of MCP and PIP joints are treated in one stage. Injecting more collagenase along the cord may also imply that a larger part of the cord is disrupted or dissolved. It is not known whether this would result in a more durable correction. Although the initial multicentre study has reported outcomes at 3 years and 5 years,6 7 the study had substantial follow-up attrition (about one-third) and the treating surgeons themselves were outcome assessors. No other prospective studies have reported outcomes at 2 years or longer.

As patients mainly have activity limitations rather than symptoms, measuring patient-reported activity limitations is important in evaluating treatment outcomes. Little is known about outcomes of collagenase treatment with regard to activity limitations up to 2 years after treatment. The purpose of this study was to determine the durability of collagenase efficacy with regard to joint contractures and activity limitations 2 years after injections.

Patients and methods

Study design and eligibility criteria

We conducted a prospective cohort study at one orthopaedic department in Southern Sweden. The department is the only centre that treats patients with Dupuytren's disease in a region with 300 000 inhabitants. The indication for treatment with collagenase injections was presence of a palpable cord and a total extension deficit of ≥20° in the MCP joint and/or PIP joint. All patients who had received at least one injection and reached 2 years after first injection from November 2013 through October 2014 were eligible.

Patients

From September 2011 through October 2012, we treated 57 consecutive patients (59 hands) with collagenase injections. In the two bilaterally treated patients the interval between treatments was 1 week and 6 months, respectively. All patients were asked to participate in a follow-up examination at a minimum of 2 years after first injection; five patients (five hands) did not participate (two deceased, one had dementia and two did not respond) and four patients (four hands) declined to attend examination but agreed to a telephone interview. Thus, 48 patients (50 hands; 85% of the treated hands) underwent physical examination at a mean of 26 (median 25, range 24–35) months after first injection (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants and non-participants in the 2-year follow-up physical examination

| Participants | Non-participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of hands/patients | 50/48 | 9/9 |

| Sex, men: women | 38:12 | 8:1 |

| Age, median (range) | 68 (51–83) | 66 (55–84) |

| Hand treated, right: left | 34:16 | 8:1 |

| Finger treated, small: ring: middle: index | 25:24:1:1 | 5:3:1:0 |

| Previous fasciectomy on treated finger, n (%) | 6 (12) | 1 (11) |

| Additional treatment visits to therapist, n (%) | 3 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Repeat injection, n (%) | 5 (10)* | 1 (11) |

| Total extension deficit† | ||

| Before injection | 80 (54, 108) | 68 (49, 119) |

| 5 weeks after injection | 15 (0, 29) | 20 (9, 63) |

*Interval: 4 weeks (one patient), 2 months (one patient), 6 months (three patients), all five had MCP and PIP contracture at baseline (three had reinjection because of inadequate PIP correction and two because of inadequate MCP and PIP correction).

†Median (25th, 75th centiles) active extension deficit (degrees) of the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the treated finger. For all treated fingers, the minimum total extension deficit was 30°.

Intervention

A hand surgeon injected collagenase into the cord using a modification of the standard technique.4 After reconstituting collagenase with 0.39 mL of diluent, the surgeon injected all reconstituted collagenase that could be withdrawn (∼0.80 mg) in the cord, distributed in three or four spots along the palpable cord, from the PIP joint to the palmar crease. After injection, a nurse applied a soft dressing and the hand therapist gave the patient verbal and written instructions regarding oedema prophylaxis and avoidance of heavy use of the hand.

The surgeon performed finger manipulation 1 day or 2 days after collagenase injection, as schedule permitted. The surgeon injected local anaesthetic (10 mL of 10 mg/mL mepivacaine buffered with sodium bicarbonate) proximal to the palmar crease (a few centimetres proximal to the collagenase injection sites) to block the nerves to the treated finger. After about a 20-minute interval, the surgeon performed finger manipulation by applying pressure with the thumb along the cord to disrupt it and then manipulating the MCP and PIP joints into maximum possible extension.

Immediately after finger manipulation, the patients went to the hand therapist and received a static splint with fingers in maximal possible extension; the therapist gave instructions on oedema management, range of motion exercises, to use the hand as tolerated during daytime and to use the splint at night for 8 weeks. The patients returned to the hand therapist after 1 week for splint adjustment. In case contracture correction was incomplete and the patient was willing to receive further treatment, the surgeon scheduled the patient for a second injection.

Measurements

Before treatment, one of three hand therapists measured active extension deficit (AED) in the fingers with a goniometer and recorded the results in a standardised protocol. The first 29 patients in the study completed the 11-item disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (QuickDASH) scale.8 At 5 weeks after injection, a hand therapist measured AED in the fingers and the first 29 patients completed the QuickDASH. At 2 years after injection, a hand therapist contacted the patients and asked them to attend the hospital for a physical examination. During this visit, the therapist measured AED as well as passive extension deficit (PED) in the fingers and examined the hand for possible treatment-related complications. The therapist asked the patients to report any symptoms from the treated hand and about their satisfaction with the results of treatment (satisfied or dissatisfied). All patients completed the QuickDASH. The same hand therapist (AL) examined all patients who attended the 2-year follow-up evaluation and telephone-interviewed patients who did not attend examination. During the telephone interview, the therapist asked the patients whether they believed their treated finger had worsened since the 5-week follow-up visit and whether they were satisfied with the results. Two of the patients interviewed by telephone also completed the QuickDASH.

We reviewed the electronic records of all participants and non-participants to ascertain any subsequent surgery or other procedures on the study hand. We also recorded the number of any additional treatment visits to the hand therapist (outside the preplanned visit at 1 week).

Statistical analysis

Sample size

The primary outcome was treatment effect durability defined as the proportion of patients that do not worsen by ≥20° in AED, in a treated joint, between the 5-week and the 2-year measurements. We considered this cut-off as clinically important because it has been used in the previous collagenase multicentre study.6 In that study, recurrence or non-durability (≥20° increase in PED in fully or partially corrected joints with presence of palpable cord, or subsequent treatment) among 924 joints was 24% at 2 years. We estimated that ∼50 patients would be eligible and a 70% participation rate. With 80% power and 5% significance level, a sample of 30 patients can show treatment effect durability among 75% of the patients.

Primary analysis

We recorded AED values for MCP and PIP joints for all treated fingers at three measurement times (baseline, 5 weeks and 2 years) and calculated the proportion of fingers that showed worsening of ≥20° in AED from the 5-week to the 2-year measurements.

Secondary analyses

In addition to AED values for all MCP and PIP joints and total (MCP+PIP) extension deficit in the treated fingers we analysed AED values for joints that had at least 10° pretreatment AED. We considered hyperextension as 0° extension deficit. As previous studies defined complete correction as PED value 0–5°,1 6 we also analysed the data according to this definition. This was possible only for the 2-year values, because we measured only AED at baseline and 5 weeks. The change in AED between evaluation times (baseline, 5 weeks and 2 years) was statistically tested with the paired t-test. We used the Mann-Whitney test to compare baseline and 5-week AED in joints that showed ≥20° AED worsening between the 5-week and 2-year measurements and joints that had not worsened (only hands that received a single injection were included in this analysis). We tested the change in QuickDASH scores with the Wilcoxon test (one score for both hands for the two bilaterally treated patients). We analysed the correlation between the changes (baseline to 2 years) in total AED and QuickDASH scores with the Pearson correlation coefficient (r). We also analysed treatment satisfaction according to changes in total AED and QuickDASH scores using analysis of covariance adjusting for sex, age and baseline total AED or QuickDASH score, respectively. We did a similar analysis for the 2-year QuickDASH scores adjusting for sex and age.

We present the data as proportions, means with SDs or 95% CIs, and/or medians with 25th and 75th centiles as appropriate. For one patient who had surgery on the treated finger 23 months after injection we used the extension deficit recorded immediately before surgery as the 2-year value in all analyses.

A two-sided p value of <0.05 indicated statistical significance. We used Stata V.14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA) for the sample size estimation and IBM SPSS Statistics V.22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) for the statistical analyses.

Results

Joint contracture

Active extension deficit

Between the 5-week and the 2-year measurements, AED had worsened by ≥20° in seven MCP and seven PIP joints (28% of the treated hands; all had received a single injection). For all treated fingers, the mean AED for the MCP joints was 54° before injection, 6° at 5 weeks and 9° at 2 years and the corresponding values for the PIP joints were 30°, 13° and 16°, respectively (table 2). Between the 5-week and 2-year measurement mean total AED had worsened by 6° (p=0.031).

Table 2.

Active extension deficit in the treated fingers immediately before collagenase injection (baseline) and at 5 weeks and 2 years after injection

| Baseline n=50 |

5 week n=50 |

2 year n=50 |

Mean difference (95% CI), p value Baseline—2 year 5 week—2 year |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCP | 54 (23) | 6 (12) | 9 (16) | 45 (38 to 52) <0.001 | −3.1 (−7.8 to 1.6) 0.20 |

| PIP | 30 (28) | 13 (17) | 16 (21) | 14 (9 to 20) <0.001 | −3.3 (−6.7 to 0.1) 0.056 |

| MCP+PIP | 84 (37) | 18 (22) | 25 (25) | 59 (51 to 68) <0.001 | −6.4 (−12 to −0.06) 0.031 |

Values are mean (SD) unless specified otherwise.

MCP, metacarpophalangeal joint; PIP, proximal interphalangeal joint.

Comparison of the baseline and 5-week AED in joints that had worsened by ≥20° AED between the 5-week and the 2-year measurements and those that had not worsened showed significant differences for the PIP but not for the MCP joints (table 3). Thus, PIP joints with a large pretreatment AED and incomplete initial correction were more likely to worsen between the 5-week and 2-year measurements than PIP joints with less severe contracture and good initial correction, but this was not the case for MCP joints. Analyses including only joints with baseline contracture of at least 10° showed similar results.

Table 3.

Baseline and 5-week active extension deficit for the joints that had worsened by ≥20° at the 2-year measurement (compared with the 5-week measurement) and the joints that had not worsened between these two measurement times; hands treated with a single collagenase injection

| Worsened ≥20° after the 5-week postinjection measurement | Not worsened after the 5-week postinjection measurement | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCP, n | 7 | 38 | |

| Baseline | 60 (40, 65) | 55 (40, 70) | 0.87 |

| 5-week | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 10) | 0.57 |

| PIP, n | 7 | 38 | |

| Baseline | 60 (30, 75) | 10 (0, 40) | 0.017 |

| 5 week | 15 (15, 55) | 0 (0, 15) | 0.004 |

Values are median (25th, 75th centiles) active extension deficit.

MCP, metatarsophalangeal joint; PIP, proximal interphalangeal joint.

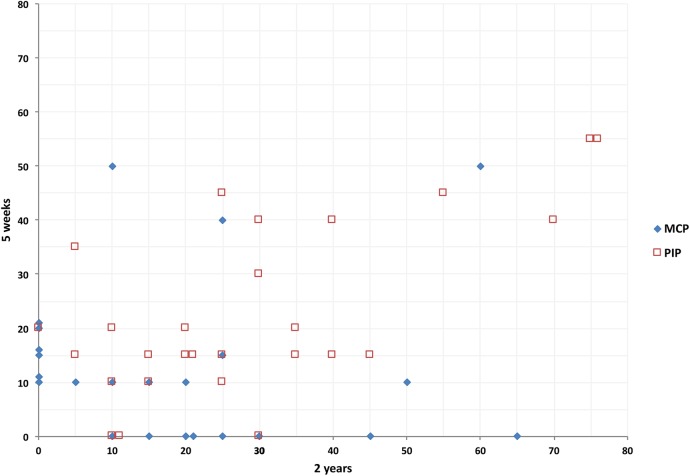

A larger proportion of PIP than MCP joints showed either persistent or increased AED (figure 1). Total AED had worsened by ≥30° in eight of the 50 hands (16%; all had received a single injection). Considering only joints with a pretreatment AED≥10° (47 MCP joints (mean 57°, SD 19) and 31 PIP joints (mean 48°, SD 21)), mean improvement in AED from baseline was 49° (95% CI 41 to 54, p<0.001) for the MCP joints and 25° (95% CI 17 to 32, p<0.001) for the PIP joints.

Figure 1.

Active extension deficit (AED) for the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints 5 weeks and 2 years after collagenase injection for Dupuytren's contracture in 50 treated fingers. The joints shown in this diagram are those with AED of at least 10° at 5 weeks or in which AED had changed between the 5-week and the 2-year measurements; AED measured with 5° intervals and joints with identical values juxtaposed for visual clarity. For example, the ♦ farthest to the right on the x-axis represents a treated finger in which MCP AED was 0° at 5 weeks and 65° at 2 years, and the □ in the upper right corner of the graph represent a treated finger in which PIP AED was 55° at 5 weeks and 75° at 2 years. In four joints a second injection after the 5-week measurement was given. Joints without contracture (AED 0–5°) at the 5-week and the 2-year measurement (27 MCP and 23 PIP joints) are not shown in the diagram.

Passive extension deficit

Of the 47 MCP and 31 PIP joints with contracture before injection, PED of 0–5° at 2 years was recorded in 39 MCP joints (83%) and in 15 PIP joints (48%). A total PED≥30° was present in 11 hands (22%). For all 50 treated fingers, mean PED for the MCP joints was 3.2° (SD 9; median 0; 25th and 75th centiles 0, 0) and for the PIP joints was 11° (SD 19; median 0; centiles 0, 20).

Telephone interview

None of the four patients telephone-interviewed at 2 years reported worsening of their treated finger after the 5-week follow-up.

Activity limitations

Of the first 29 patients (30 hands) to whom the QuickDASH was administered at baseline, one had subsequent surgery before and one did not participate in the 2-year follow-up. For the remaining 27 patients (28 hands) the median score (25th, 75th centiles) at baseline was 11 (2, 21), at 5 weeks was 3 (0, 9) and at 2 years was 2 (0, 18). Changes from baseline to 5 weeks and to 2 years were statistically significant (p<0.001 and p=0.034, respectively) but not changes from 5 weeks to 2 years (p=0.45). The correlation between baseline to 2 years changes in total AED and QuickDASH score was moderate (r=0.49, p=0.010). For all 49 patients who completed the QuickDASH at 2 years, the median score was 3 (0, 18).

Patient satisfaction

The patients reported satisfaction with treatment results in 41 of the 50 hands examined and four hands evaluated with telephone interview (83% satisfied). Mean change (improvement) in total AED from baseline to 2 years among ‘satisfied’ patients was 65 (SD 26) and among ‘dissatisfied’ patients was 39 (SD 36); adjusted mean difference 37 (95% CI 26 to 49, p<0.001). Mean change in QuickDASH score for the satisfied patients was −8 (SD 10) and for the dissatisfied patients 1 (SD 25); adjusted mean difference −12 (95% CI −23 to −2, p=0.047). Mean 2-year QuickDASH score for ‘satisfied’ patients was 9 (SD 15) and for ‘dissatisfied’ patients 26 (SD 13); adjusted mean difference −16 (95% CI −27 to −5, p=0.007).

Subsequent surgery and adverse events

One patient had recurrent MCP contracture after one injection and chose to have limited fasciectomy, which was performed 23 months after injection. No other patients had surgery or needle fasciotomy. At the 2-year follow-up evaluation, the examining therapist did not observe and the patients did not report any treatment-related adverse events.

Discussion

This prospective cohort study of patients with Dupuytren's disease treated with collagenase injection shows that contracture improvement was maintained 2 years after treatment in three of four patients. However, up to 20% of the patients were not satisfied (assuming that the two patients who did not respond also were dissatisfied), possibly because of incomplete initial correction or recurrent contracture in the treated finger. Considering its relative simplicity compared with fasciectomy the results of this the 2-year treatment effect durability assessment support the continued use of collagenase injection as an effective treatment option in patients with Dupuytren's disease.

Assuming, hypothetically, that all patients with total PED≥30° at 2 years receive a new injection (implying almost a third of all patients would need two injections), treatment costs as estimated in a previous study,4 would still be lower than costs of surgery. The comparison involves only direct treatment costs and does not take into consideration costs of possible surgical complications.4 Since patients with good results may still experience worsening after 2 years, a new assessment with longer follow-up is necessary.

Most patients received a single injection but about 10% of the patients needed a second injection because the initial reduction was inadequate. Similar to previous studies of collagenase and surgery, outcomes were better for MCP joints than PIP joints; more than 80% of MCP joints but less than half of PIP joints achieved complete correction. The PIP joints that had worsened after the 5-week follow-up had more severe contracture before treatment and at 5 weeks (inadequate correction), but this was not the case for MCP joints. This may suggest that in case the first injection fails to achieve adequate correction for PIP joints the surgeon should consider a second injection early. This question needs further study.

Comparison with other collagenase studies

We measured AED before treatment and at 5 weeks and 2 years. We measured PED only at 2 years to facilitate comparison with previous studies. With regard to joint contracture, passive deficit would be equal or less than active deficit. Thus, our posttreatment AED values are conservative when compared with studies that reported posttreatment PED values.

In the Collagenase Option for Reduction of Dupuytren Long-Term Evaluation of Safety Study (CORDLESS), 621 of 950 (65%) of the initial study participants could be followed.6 The authors defined ‘recurrence’ as contracture worsening by ≥20° combined with presence of palpable cord or further treatment including injection, in successfully treated joints (0–5° extension deficit; 70% of treated MCP and 40% of treated PIP), implying that joints in which treatment had initially failed were excluded. Same definition applied to partially corrected joints (improved by ≥20°) was termed ‘non-durability’. At 2 years, recurrence had occurred in 20% and non-durability in 33%. At 3 years, contracture ‘worsening’ (defined as ≥20° increase in contracture in fully or partially corrected joints with or without palpable cord, or subsequent treatment) was 28% for MCP and 58% for PIP; no 2-year data for ‘worsening’ are available. The study reported that for successfully treated MCP joints mean PED at baseline was 37 (SD 16) and at 2 years was 8 (SD 13), and for PIP joints 38 (SD 16) and 20 (SD 19), respectively,6 and a substantial number of patients received multiple injections. In our study, mean PED for the MCP and PIP joints at 2 years was 3 (SD 9) and 11 (SD 19), respectively.

As we measured PED only at 2 years, it is not possible to make a direct comparison with the CORDLESS study, but we can assume that PED is always equal or less than AED. Of 32 hands with baseline MCP joint AED of 25° or more and AED of 0–5° at 5 weeks (ie, ‘successfully treated’ according to CORDLESS definition), two had PED≥20° at 2 years and one had undergone surgery, thus 9% would be defined as recurrence according to CORDLESS. This is an overestimate because in the CORDLESS study the definition of recurrence required that patients had contracture worsening and palpable cord, and a large number of different surgeons recorded presence of palpable cord (validity uncertain). Although it is difficult to compare results because of differences in definitions, our results appear to be more favourable. A study of 47 patients with one MCP contracture (30–60°) and no PIP contracture, treated with a single 0.58 mg collagenase injection, reported a 25% 2-year recurrence (>20° contracture).9

Comparison with limited fasciectomy and percutaneous needle fasciotomy

Although many studies have reported fasciectomy results,10 we believe only prospective studies with high follow-up participation can provide good-quality outcomes data. A recent prospective study of 90 patients treated with limited fasciectomy at a university hand surgery centre in Sweden, reported that at 1 year the mean AED for the MCP joints was 5 (SD 9) and for the PIP joints 22 (SD 18).11 It is unclear whether the authors used 0° for hyperextension (as in our study) or used the actual values, which would underestimate the reported extension deficit. They reported that 81% were satisfied at 1 year. Thus, our 2-year collagenase results compare favourably with the 1-year results after limited fasciectomy. Surgery-related complications reported in the study included nerve injury (four patients) and complex regional pain syndrome (four patients) and many patients required extensive therapy.11 Collagenase treatment does not require extensive hand therapy. Almost all patients required only two hand therapist visits (immediately after finger manipulation and at 1 week for splint adjustment).

In a randomised study that defined recurrence after needle fasciotomy as ≥30° worsening in the treated finger's total PED from 6 weeks to 2 years, 29 of 52 patients (56%) had recurrence.12 Applying the same definition to our study but using total AED, eight of 50 hands (16%) would be defined as having recurrence.

The Swedish National Quality Register for Hand Surgery have reported outcome data for patients treated for Dupuytren's contracture at the Swedish Hand Surgery departments between 2010 and 2014.13 The mean DASH score in patients treated with collagenase had improved from 23 before (n=399) to 11 at 1 year (n=250); the corresponding values for limited fasciectomy were 24 (n=273) and 11 (n=252) and for needle fasciotomy 25 (n=52) and 17 (n=54), respectively. The average patient satisfaction (visual analog scale from 0 to 100) after collagenase treatment (n=260) was 78%, after limited fasciectomy (n=262) was 79% and after closed fasciotomy (n=73) was 69%.13 A Swedish two-centre randomised study of collagenase versus needle fasciotomy found no differences at 1 year, but it included mainly patients with only MCP contractures and the treating surgeons measured the outcomes.14

We do not use the outcome ‘recurrence’ because of lack of consensus about the definition of recurrence. Treatment with collagenase inherently implies that part of the cord is left intact and therefore it would be impossible to know with acceptable certainty whether a presence of a cord is indicative of recurrence. We believe the degree of joint contracture before and after treatment is a more valid measure of outcome irrespective of whether the cause of the contracture is incomplete correction, disease recurrence/progression or other cause.

Activity limitations

We used the QuickDASH as patient-reported measure of activity limitations and the results show that the scores improved significantly after treatment. The magnitude of improvement differed according to changes in joint contracture and with patient satisfaction. As the median pretreatment QuickDASH score was relatively low, it may not be appropriate in studies comparing different treatments because it would be difficult to detect important between-group differences. However, in patients with Dupuytren's disease, there are no established thresholds for within-group and between-group differences in QuickDASH score, considered as clinically important. Besides, it is not obvious that the same threshold should apply to complex treatments that include surgery and extensive rehabilitation as to less invasive treatments that are associated with substantially lower risks and burden on patients.

The limitations of our study include a single centre and a moderate sample size, implying uncertain generalisability. We did not measure passive but only AED at baseline and at 5 weeks after injection and only the first 29 patients completed the QuickDASH at these follow-up times. Another limitation is lack of 12-month follow-up. Further, patients stated whether they were satisfied or not satisfied with the results at 2 years; a scale with more response options might have yielded different results. Our study has several strengths. First, hand therapists measured joint contractures at baseline, 5 weeks and 2 years, independent of the treating surgeon and a validated scale used to measure patient-reported activity limitations. The high participation rate is a major strength with 2-year outcomes data available for 95% of the treated hands of patients still living.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Department of Orthopedics and Department of Rehabilitation Hässleholm Hospital and Region Skåne, Sweden. The authors thank Jonas Ranstam, Former Professor of Medical Statistics, Department of Clinical Sciences, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, for statistical advice.

Footnotes

Contributors: AL contributed to study design, collected the data, assisted in the analysis and interpretation of the data, contributed to drafting of the manuscript and approved the final version submitted for publication. IA led the project, designed the study, conducted data analysis and interpretation, contributed to drafting of the manuscript and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: IA was a member of an Expert Group on Dupuytren's disease for Pfizer in 2012 and has participated in meetings organised by Sobi.

Ethics approval: This research was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund (2013/656) and conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2000. All patients received full verbal and written information about the study and gave informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hurst LC, Badalamente MA, Hentz VR et al. Injectable collagenase clostridium histolyticum for Dupuytren's contracture. N Engl J Med 2009;361:968–79. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKeage K, Lyseng-Williamson KA. Collagenase clostridium histolyticum in Dupuytren's contracture: a guide to its use in the EU. Drugs Ther Perspect 2016;32:131–7. 10.1007/s40267-016-0291-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaston RG, Larsen SE, Pess GM et al. The efficacy and safety of concurrent collagenase clostridium histolyticum injections for 2 Dupuytren contractures in the same hand: a prospective, multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am 2015;40:1963–71. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.06.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atroshi I, Strandberg E, Lauritzson A et al. Costs for collagenase injections compared with fasciectomy in the treatment of Dupuytren's contracture: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004166 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atroshi I, Nordenskjöld J, Lauritzson A et al. Collagenase treatment of Dupuytren's contracture using a modified injection method: a prospective cohort study of skin tears in 164 hands, including short-term outcome. Acta Orthop 2015;86:310–15. 10.3109/17453674.2015.1019782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peimer CA, Blazar P, Coleman S et al. Dupuytren contracture recurrence following treatment with collagenase clostridium histolyticum (CORDLESS study): 3-year data. J Hand Surg Am 2013;38:12–22. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peimer CA, Blazar P, Coleman S et al. Dupuytren contracture recurrence following treatment with collagenase clostridium histolyticum (CORDLESS [Collagenase Option for Reduction of Dupuytren Long-Term Evaluation of Safety Study]): 5-year data. J Hand Surg Am 2015;40:1597–605. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gummesson C, Ward MM, Atroshi I. The shortened disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire (QuickDASH): validity and reliability based on responses within the full-length DASH. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2006;7:44 10.1186/1471-2474-7-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McFarlane J, Syed AM, Sibly TF. A single injection of collagenase clostridium histolyticum for the treatment of moderate Dupuytren's contracture: a 2 year follow-up of 47 patients. J Hand Surg Eur 2016;41:664–5. 10.1177/1753193415597421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodrigues JN, Becker GW, Ball C et al. Surgery for Dupuytren's contracture of the fingers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;12:CD010143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engstrand C, Krevers B, Nylander G et al. Hand function and quality of life before and after fasciectomy for Dupuytren contracture. J Hand Surg Am 2014;39:1333–43. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Rijssen AL, ter Linden H, Werker PM. Five-year results of a randomized clinical trial on treatment in Dupuytren's disease: percutaneous needle fasciotomy versus limited fasciectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012;129:469–77. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31823aea95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.HAKIR—Swedish National Quality Register for Hand Surgery. Annual Report 2014. 21–22. http://hakir.se/rapporter/ (accessed 3 Jan 2017).

- 14.Scherman P, Jenmalm P, Dahlin LB. One-year results of needle fasciotomy and collagenase injection in treatment of Dupuytren's contracture: a two-centre prospective randomized clinical trial. J Hand Surg Eur 2016;41:577–82. 10.1177/1753193415617385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]