Abstract

Objective

To evaluate effects of the anti-interleukin-6 receptor monoclonal antibody sarilumab administered with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in the TARGET trial in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with inadequate response or intolerance to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNF-IR).

Methods

546 patients (81.9% female, mean age 52.9 years) were randomised to placebo, sarilumab 150 or 200 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks + csDMARDs. PROs included patient global assessment (PtGA); pain and morning stiffness visual analogue scales; Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI); Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36); FACIT-Fatigue (FACIT-F); Work Productivity Survey-Rheumatoid Arthritis (WPS-RA) and Rheumatoid Arthritis Impact of Disease (RAID). Changes from baseline at weeks 12 and 24 were analysed using a mixed model for repeated measures; post hoc analyses included percentages of patients reporting improvements ≥ minimum clinically important differences (MCID) and scores ≥ normative values.

Results

Sarilumab + csDMARDs doses resulted in improvements from baseline at week 12 vs placebo + csDMARDs in PtGA, pain, HAQ-DI, SF-36 and FACIT-F that were maintained at week 24. Sarilumab improved morning stiffness and reduced the impact of RA on work, family, social/leisure activities participation (WPS-RA) and on patients' lives (RAID). Percentages of patients reporting improvements ≥MCID and ≥ normative scores were greater with sarilumab than placebo.

Conclusions

In patients with TNF-IR RA, 150 and 200 mg sarilumab + csDMARDs resulted in clinically meaningful patient-reported benefits on pain, fatigue, function, participation and health status at 12 and 24 weeks that exceeded placebo + csDMARDs, and were consistent with the clinical profile previously reported.

Trial registration number

NCT01709578; Results.

Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Outcomes research, DMARDs (biologic), Anti-TNF, Patient perspective

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

While sarilumab has demonstrated significant improvement in symptomatic, functional and radiographic outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) clinical trials, assessing patient-reported outcomes (PROs) is an important consideration when making treatment decisions.

What does this study add?

This analysis shows that treatment with sarilumab with conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) resulted in statistically or nominally significant improvements in PROs in patients with an inadequate response or intolerance to tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors (TNF-IR) in moderate-to-severely active RA.

Patients reported benefits of sarilumab on specific domains of importance, including pain, fatigue, morning stiffness, physical function, participation and reduced impact of disease on their general health status: the percentages reporting improvements ≥ minimum clinically important differences and that met or exceeded normative values were greater with sarilumab than placebo.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

In addition to clinical responses, sarilumab provides meaningful, important benefits in outcomes of importance to patients.

Introduction

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are important endpoints that supplement physician-reported and laboratory measures when evaluating treatment responses in rheumatoid arthritis (RA).1–3 Clinical measures of RA such as the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response criteria incorporate PROs that capture pain, physical function and global assessment of disease.4 However, PROs that assess fatigue, health-related quality of life (HRQOL) or health status and effects of RA on work within and outside the home and family, social and leisure activities are not routinely part of assessment of disease activity, but are important since these outcomes have profound effects on patients' daily lives.5–8

Sarilumab is a human immunoglobulin (IgG1) anti-interleukin-6 receptor α (anti–IL-6Rα) monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to membrane-bound and soluble IL-6Rα, inhibiting IL-6-mediated signal transduction;9 IL-6 contributes to inflammation and joint destruction10 and mediates pain and fatigue in RA.11 12 Sarilumab was evaluated in two phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled trials (RCTs), MOBILITY and TARGET. Consistent with international consensus and guidelines,1–4 and the importance of the patient perspective, PROs were assessed in both pivotal sarilumab trials. The MOBILITY RCT,13 which evaluated sarilumab in combination with methotrexate (MTX) in moderate-to-severe patients with RA with inadequate responses to MTX, demonstrated benefits across multiple PROs, including patient global assessment of disease activity (PtGA), pain, physical function, fatigue and general health status compared with placebo. The TARGET trial evaluated sarilumab in combination with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) in patients with moderate-to-severe RA with inadequate responses or intolerance to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNF-IR). Subcutaneous administration of sarilumab 200 and 150 mg every 2 weeks (q2w) demonstrated significant improvement in symptomatic and functional outcomes, with a safety profile consistent with IL-6 blockade.14 This paper reports the effects of sarilumab treatment on the PROs included in the TARGET RCT.

Methods

Study design and population

Details of the TARGET multicentre RCT have been previously described;14 briefly, patients with TNF-IR RA received subcutaneous placebo or sarilumab 150 or 200 mg q2w + csDMARDs for 24 weeks. At week 12 and onwards, patients with <20% improvement from baseline in swollen or tender joint counts for at least two consecutive assessments separated by ≥4 weeks were offered rescue with open-label sarilumab 200 mg q2w. The first patient was enrolled in October 2012, and the last completed the trial in March 2015. This RCT received approval from the Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee of the investigational centres and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki; all patients provided written, informed consent prior to participation (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01709578).

Inclusion criteria included: age ≥18 years; diagnosis of RA by ACR/The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) 2010 classification criteria;15 moderate-to-severely active disease; disease duration ≥6 months; inadequate responses or intolerance to ≥1 TNFi and continuous treatment with standard dose(s) of ≥1 csDMARDs (combination MTX + leflunomide was not allowed) for ≥12 weeks before baseline and stable doses ≥6 weeks before screening. Patients were excluded if they had uncontrolled concomitant diseases, significant extra-articular manifestations of RA, functional class IV RA, other inflammatory diseases, current/recurrent infections or were receiving prednisone (or equivalent) >10 mg/day.

Patient-reported outcomes

All PROs were translated into the appropriate languages, and included PtGA and pain, both evaluated using a 0–100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) and Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI), all of which were assessed as part of the ACR response criteria.4 The Medical Outcomes SF-36 Health Survey V.2 (SF-36)16 assesses eight domains (physical functioning (PF), role physical (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health perceptions (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role emotional (RE) and mental health (MH)) on a scale of 0–100 with higher scores indicating better health status, combined into physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) component summary scores with normative values of 50 and SDs of 10.

Other PROs included Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F),17 Work Productivity Survey-Rheumatoid Arthritis (WPS-RA),18 Rheumatoid Arthritis Impact of Disease (RAID)19 and morning stiffness using a 0–100 mm VAS.20 The WPS-RA consists of nine items, assessing employment status, productivity with regard to absenteeism (days missed), presenteeism (days with work productivity reduced by ≥50%) and rate of RA interference in work within and outside the home (0 = no interference to 10 = complete interference), as well as participation measured as days missed in family, leisure and social activities, all with a 1-month recall period. The RAID is a composite measure based on seven domains (pain, functional disability, fatigue, physical and emotional well-being, quality of sleep and coping) scored on 0–10 numerical rating scales (NRS); weighted by patient assessment of relative importance, with higher scores indicating greater impact of RA.

PtGA, pain and HAQ-DI were evaluated at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 24. Change from baseline in HAQ-DI at week 12 was a coprimary endpoint. SF-36 and WPS-RA were assessed at baseline and weeks 4, 12 and 24. FACIT-F, RAID and morning stiffness were assessed at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 12 and 24.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were based on the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, which included all randomised patients. A mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) tested least square mean (LSM) changes from baseline between each active treatment group and placebo at weeks 12 and 24. The MMRM included treatment, region, number of previous TNFi, visit and treatment-by-visit interaction as fixed effects and baseline PRO scores as covariates. Data collected after treatment discontinuation or rescue were set to missing. Statistical significance was claimed for those outcomes above the break in the predefined hierarchy; otherwise, p values are considered nominal. As the WPS-RA consists of independent items, O'Brien's global test was first used to determine overall significance at week 24 prior to further evaluation.21

Responder analyses evaluated the proportion of patients who reported improvements meeting or exceeding minimum clinically important differences (MCID) for each PRO.22 23 These were prespecified for HAQ-DI using MCID values ≥0.2222 and ≥0.3,24 25 and conducted post hoc for other endpoints based on 10 points for PtGA,26 pain and morning stiffness VAS scales;23 27 2.5 points for SF-36 PCS and MCS, and 5 points for individual domains;28 4 points in FACIT-F17 and 3 points for RAID.29 Patients who discontinued treatment (placebo, n=17; sarilumab 150 mg, n=31; sarilumab 200 mg, n=25) or used rescue medication (placebo, n=63; sarilumab 150 mg, n=25; sarilumab 200 mg, n=26) were considered non-responders, and differences in proportions between treatments were evaluated using a two-sided Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test (stratified by number of previous anti-TNFs and region). Estimates of the number-needed-to-treat (NNT), ie, the number of patients who must be treated to obtain the outcome of interest in one patient, were calculated as the reciprocal of the differences in responder rates between sarilumab and placebo for patients who reported improvements ≥MCID at week 24.30 In addition to the overall population, the percentage of PRO responders in the subpopulation of ACR20 responders was determined post hoc. Other post hoc analyses included the proportion of patients who reported normative values in FACIT-F and SF-36 PCS, MCS and domain scores at week 24.

Post hoc correlation analysis (Pearson r) explored potential relationships between reported individual PRO scores at week 24 and clinical measures of disease activity (28-joint Disease Activity Score using C reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI)).

All analyses were performed using SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, SC).

Results

Demographic and disease characteristics

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics were balanced across treatment groups (table 1). Patients were predominantly female (81.9%), with a mean duration of RA since diagnosis of 12.1 years and all were patients with TNF-IR. Most patients (92.3%) had failed their previous agent due to inadequate responses, of these, 42% were recorded as having a primary failure to the prior TNF, and 58% as having secondary failures. A total of 20.6–25.4% across treatment groups of the total population had received >1 prior TNFi.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics*

| Sarilumab |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Placebo +csDMARDs (n=181) | 150 mg q2w+csDMARDs (n=181) | 200 mg q2w+csDMARDs (n=184) |

| Age, years | 51.9±12.4 | 54.0±11.7 | 52.9±12.9 |

| Female, n (%) | 154 (85.1) | 142 (78.5) | 151 (82.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 124 (68.5) | 134 (74.0) | 130 (70.7) |

| Black | 7 (3.9) | 8 (4.4) | 5 (2.7) |

| Asian | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.5) |

| Other | 49 (27.1) | 36 (19.9) | 48 (26.1) |

| Geographic region, n (%)† | |||

| Region 1 | 77 (42.5) | 77 (42.5) | 79 (42.9) |

| Region 2 | 74 (40.9) | 74 (40.9) | 74 (40.2) |

| Region 3 | 30 (16.6) | 30 (16.6) | 31 (16.8) |

| Duration of RA, years | 12.0±10.0 | 11.6±8.6 | 12.7±9.6 |

| Prior anti-TNF exposure, n (%) | 181 (100) | 181 (100) | 184 (100) |

| 1 | 135 (74.6) | 143 (79.4) | 140 (76.5) |

| >1 | 46 (25.4) | 37 (20.6) | 43 (23.5) |

| Reason for anti-TNF failure, n (%) | |||

| Inadequate response | 174 (96.1) | 163 (90.1) | 167 (90.8) |

| Intolerance | 6 (3.3) | 17 (9.4) | 15 (8.2) |

| Other | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) |

| Rheumatoid factor positive, n (%) | 142 (78.9) | 135 (74.6) | 132 (72.9) |

| Anti-CCP antibody positive, n (%) | 150 (83.3) | 135 (75.0) | 137 (76.1) |

| DAS28-CRP | 6.2±0.9 | 6.1±0.9 | 6.3±1.0 |

| Tender joint count (of 68 joints) | 29.4±14.5 | 27.7±15.6 | 29.6±15.5 |

| Swollen joint count (of 66 joints) | 20.2±11.3 | 19.6±11.2 | 20.0±11.9 |

| PtGA VAS‡ | 68.8±18.1 | 67.7±17.5 | 70.9±17.4 |

| Pain VAS‡ | 71.6±18.2 | 71.0±19.3 | 74.9±18.4 |

| HAQ-DI§ | 1.8±0.6 | 1.7±0.6 | 1.8±0.6 |

| FACIT-F¶ | 23.7±10.8 | 23.5±10.6 | 23.1±10.8 |

| SF-36 PCS** | 29.7±7.8 | 30.3±6.7 | 29.4±6.7 |

| SF-36 MCS** | 38.5±12.6 | 38.6±11.4 | 39.1±11.4 |

| RAID score†† | 6.6±2.0 | 6.5±2.0 | 6.8±1.8 |

| Morning stiffness VAS‡ | 66.8±24.1 | 69.9±21.6 | 71.2±22.6 |

| WPS-RA (n)‡‡ | |||

| Work days missed due to arthritis | 4.1±6.7 (32) | 3.3±6.1 (43) | 4.0±7.1 (45) |

| Days with work productivity reduced by ≥50% due to arthritis | 6.7±8.1 (32) | 6.4±9.2 (43) | 6.9±8.5 (45) |

| Rate of arthritis interference with work productivity§§ | 5.0±2.9 (32) | 4.9±2.8 (42) | 5.1±3.4 (45) |

| House work days missed due to arthritis | 8.6±9.2 (101) | 9.5±9.7 (126) | 9.9±10.5 (133) |

| Days with household work productivity reduced by ≥50% due to arthritis | 10.0±10.1 (101) | 9.1±8.9 (125) | 9.4±9.0 (133) |

| Rate of arthritis interference with household work productivity§§ | 5.7±3.2 (100) | 6.2±2.8 (126) | 6.5±2.8 (132) |

| Days with outside help hired due to arthritis | 4.9±9.5 (101) | 5.2±9.1 (126) | 6.7±11.3 (133) |

| Days with family, social or leisure activities missed due to arthritis | 5.2±8.5 (101) | 5.3±8.0 (127) | 5.6±8.9 (133) |

*Values are the mean±SD unless indicated otherwise.

†Region 1: Australia, Canada, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Israel, Italy, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain, USA. Region 2: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru. Region 3: Lithuania, Poland, Russia, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine.

‡Scale range, 0–100; lower scores indicate better outcomes.

§Scale range, 0–3; lower scores represent less difficulty with physical functioning.

¶Scale range, 0–52; higher scores represent less fatigue.

**Scale range, 0–100; higher scores represent less impaired physical/mental health status.

††Scale range, 0–10; higher scores indicate a greater (negative) impact of RA.

‡‡Number of patients with assessment at baseline and week 24.

§§Scale of 0=no interference to 10=complete interference.

Anti-CCP, anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide; anti-TNF, anti-tumour necrosis factor inhibitor; csDMARDs, conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; DAS28-CRP, 28-joint disease activity using C reactive protein; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue scale; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; PtGA, patient global assessment of disease activity; q2w, every 2 weeks; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RAID, Rheumatoid Arthritis Impact of Disease; SF-36, Short Form 36 Health Survey V.2; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Baseline PRO scores were balanced across treatment groups (table 1), and indicative of substantial disease-associated impairment. At baseline, 33.1%, 33.7% and 35.7% of patients in placebo, sarilumab 150 and 200 mg groups, respectively, reported they were currently employed outside of the home based on the WPS-RA. Baseline values for the individual WPS-RA items indicated a substantial impact of RA on productivity within and outside the home, and >5 days missed participating in family, social and leisure activities during the past month (table 1).

Changes from baseline

There were no treatment-by-visit interactions. LSM changes from baseline at week 12 in PtGA and pain were greater with sarilumab 150 and 200 mg than placebo (both p<0.0001), and at week 24 (150 mg; p<0.001; 200 mg: p<0.0001; table 2). Compared with placebo, statistically significant improvements in change from baseline in HAQ-DI were reported with both doses of sarilumab at weeks 12 (p<0.001) and 24 (p<0.05), and SF-36 PCS at week 24 (p<0.001). Greater improvements reported with both sarilumab doses versus placebo at week 12 in FACIT-F, morning stiffness, SF-36 PCS and MCS and RAID (p<0.05) were maintained at week 24 with the exception of SF-36 MCS (table 2). Improvements in PtGA, pain, HAQ-DI and FACIT-F scores were reported at 2 weeks after start of treatment (see online supplementary figure S1).

Table 2.

Change from baseline in patient-reported outcomes at weeks 12 and 24

| Least square mean change ± SE (n) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 12 |

Week 24 |

|||||

| Patient-reported outcome | Placebo+csDMARDs (n=181) | Sarilumab 150 mg q2w+csDMARDs (n=181) | Sarilumab 200 mg q2w+csDMARDs (n=184) | Placebo+csDMARDs (n=181) | Sarilumab 150 mg q2w+csDMARDs (n=181) | Sarilumab 200 mg q2w+csDMARDs (n=184) |

| PtGA | −13.8±1.8 (172) | −25.3±1.8 (165)* | −27.4±1.8 (171)* | −19.8±2.2 (100) | −29.6±2.1 (127)† | −31.3±2.0 (136)* |

| Pain VAS | −15.1±1.9 (171) | −26.9±1.9 (166)* | −30.6±1.9 (171)* | −21.3±2.3 (98) | −31.9±2.1 (127)† | −33.7±2.0 (135)* |

| HAQ-DI | −0.26±0.04 (170) | −0.46±0.04 (165)†§ | −0.47±0.04 (171)†§ | −0.34±0.05 (101) | −0.52±0.05 (127)‡§ | −0.58±0.05 (136)‡§ |

| FACIT-F | 5.6±0.7 (169) | 8.0±0.7 (165)‡ | 9.5±0.7 (172)* | 6.8±0.9 (98) | 9.9±0.8 (126)‡ | 10.1±0.8 (136)‡ |

| Morning stiffness | −13.4±2.1 (171) | −27.3±2.1 (165)* | −29.4±2.1 (172)* | −21.7±2.4 (101) | −32.3±2.2 (127)† | −33.8±2.1 (136)* |

| RAID | −1.3±0.2 (167) | −2.3±0.2 (162)* | −2.5±0.2 (171)* | −1.8±0.2 (99) | −2.6±0.2 (126)‡ | −2.8±0.2 (136)† |

| SF-36 summary scores | ||||||

| PCS | 3.7±0.6 (169) | 6.9±0.6 (160)* | 6.8±0.6 (165)* | 4.4±0.7 (99) | 7.7±0.7 (123)†§ | 8.5±0.6 (134)*§ |

| MCS | 3.5±0.7 (169) | 5.1±0.8 (160) | 6.5±0.7 (165)‡ | 4.7±0.9 (99) | 6.3±0.8 (123) | 6.8±0.8 (134) |

| SF-36 domains | ||||||

| Physical functioning | 6.7±1.7 (170) | 14.7±1.7 (165)† | 14.7±1.7 (171)† | 8.5±2.0 (99) | 16.1±1.9 (126)‡§ | 16.8±1.8 (135)‡§ |

| Role physical | 10.3±1.7 (170) | 16.8±1.7 (162)‡ | 16.3±1.7 (169)‡ | 10.8±2.0 (99) | 17.9±1.9 (126)‡§ | 19.9±1.8 (135)†§ |

| Bodily pain | 11.6±1.5 (170) | 22.0±1.6 (164)* | 24.3±1.5 (170)* | 16.8±1.9 (99) | 24.3±1.8 (127)‡§ | 27.7±1.7 (135)*§ |

| General health | 6.4±1.3 (170) | 8.8±1.3 (164) | 10.9±1.3 (169)‡ | 8.3±1.5 (99) | 11.9±1.4 (127) | 14.8±1.4 (135)‡§ |

| Vitality | 8.5±1.4 (170) | 13.1±1.5 (165)‡ | 15.1±1.4 (171)† | 9.2±1.7 (99) | 14.5±1.6 (127)‡§ | 16.6±1.5 (135)†§ |

| Social functioning | 9.1±1.7 (170) | 17.2±1.7 (165)† | 16.2±1.7 (171)‡ | 12.9±2.1 (99) | 19.3±2.0 (127)‡§ | 19.6±1.9 (135)‡§ |

| Role emotional | 8.2±1.9 (169) | 12.6±1.9 (161) | 13.6±1.9 (168)‡ | 10.5±2.2 (99) | 14.3±2.0 (124) | 15.0±2.0 (135) |

| Mental health | 5.3±1.3 (170) | 7.8±1.3 (165) | 12.1±1.3 (171)* | 8.0±1.6 (99) | 10.8±1.5 (127) | 12.7±1.4 (135)‡§ |

For continuous endpoints, in the primary analysis, data collected after treatment discontinuation or rescue were set to missing, hence the N values quoted for change from baseline analyses were lower than the total N for each treatment group.

*p≤0.0001, †p<0.001 and ‡p<0.05 vs placebo+csDMARDs.

§Statistically significant; all other p values are nominal.

csDMARDs, conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue scale; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; PtGA, patient global assessment of disease activity; q2w, every 2 weeks; RAID, Rheumatoid Arthritis Impact of Disease; SF-36, Short Form 36 Health Survey V.2; VAS, visual analogue scale.

rmdopen-2016-000416supp_figures.pdf (355.1KB, pdf)

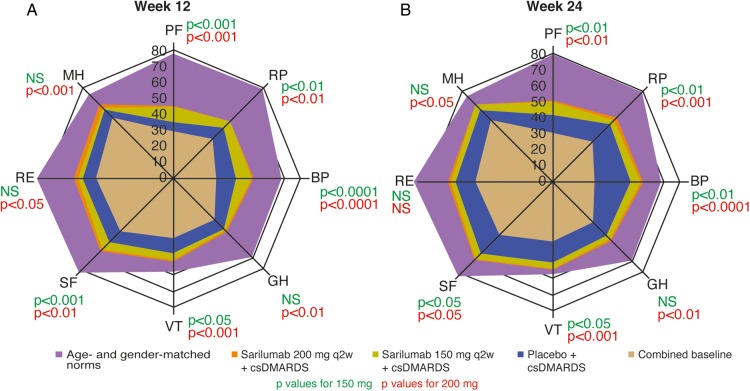

As shown in figure 1, baseline scores indicated substantial decrements across all SF-36 domains relative to US normative values for an age-matched and gender-matched population, as a benchmark comparison. Improvements were reported across all SF-36 domains at weeks 12 and 24, and were greater with sarilumab (p<0.05) with the exceptions of GH, RE and MH with 150 mg at weeks 12 and 24 and RE with 200 mg at week 24 (table 2 and figure 1). Mean week 24 scores in the 200 mg sarilumab group approached normative values for the VT domain (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Spydergram of mean SF-36 domain scores at baseline and weeks 12 (A) and 24 (B) for sarilumab 150 mg and 200 mg+csDMARDs compared with placebo+csDMARDs relative to age- and gender-matched general population norms. All scores on a scale of 0 to 100 (0=worst, 100=best). For week 12, n=181 for placebo, n=165 for sarilumab 150 mg and n=184 for sarilumab 200 mg; for week 24, n=99 for placebo, n=126 for sarilumab 150 mg and n=135 for sarilumab 200 mg. BP, Bodily Pain; GH, General Health Perceptions; MH, Mental Health; NS, not significant; PF, Physical Functioning; RE, Role Emotional; RP, Role Physical; SF, Social Functioning; VT, Vitality.

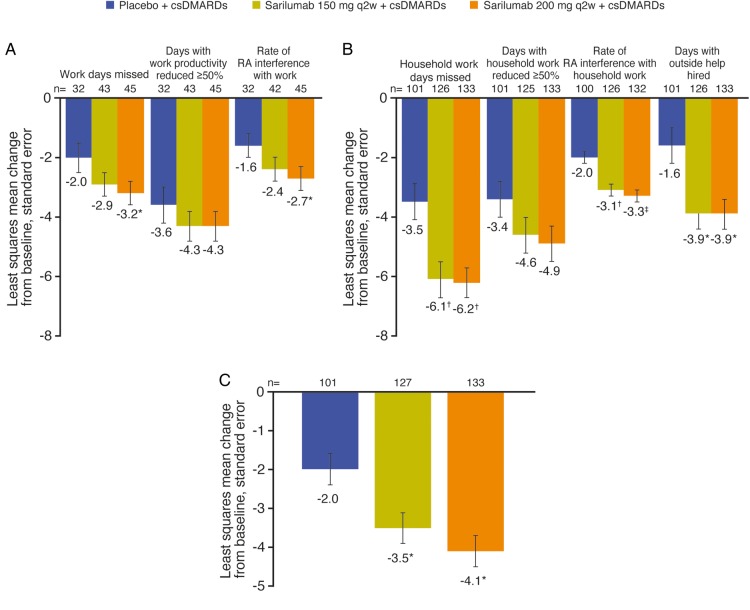

Global testing indicated that sarilumab treatment resulted in greater overall improvement in the WPS-RA compared with placebo at week 24 (p=0.0004 and p=0.0003 for 150 and 200 mg dose groups, respectively). Among those employed outside the home, patients reported reduced lost productivity due to presenteeism (ie, days with work productivity reduced by ≥50%) with the largest benefit on absenteeism (days missed), with the 200 mg dose versus placebo (−3.2 vs −2.0; p<0.05). Patients receiving sarilumab 200 mg also reported greater reductions in the rate of RA interference with work productivity (−2.7 vs −1.6; p<0.05; figure 2A). Both sarilumab doses resulted in greater reductions versus placebo in work days within the home missed (p<0.001), days with outside help required (p<0.05) and the rate of RA interference with household work (p<0.001; figure 3B). The number of days missed of family, social or leisure activities was reduced from baseline by 2.0 days with placebo compared with greater reductions with sarilumab: 3.5 days with 150 mg (p<0.05) and 4.1 days (p<0.001) with 200 mg (figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Change from baseline at week 24 in Work Productivity Survey-Rheumatoid Arthritis; recall period is the past month. (A) Work outside of the home. (B) Household work. (C) Days missed of family, social, leisure activities. Scale for rate of interference is 0=no interference to 10=complete interference; all other scales represent days. *p<0.05 vs placebo; †p<0.0001 vs placebo; ‡p<0.001 vs placebo. csDMARDs, conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs.

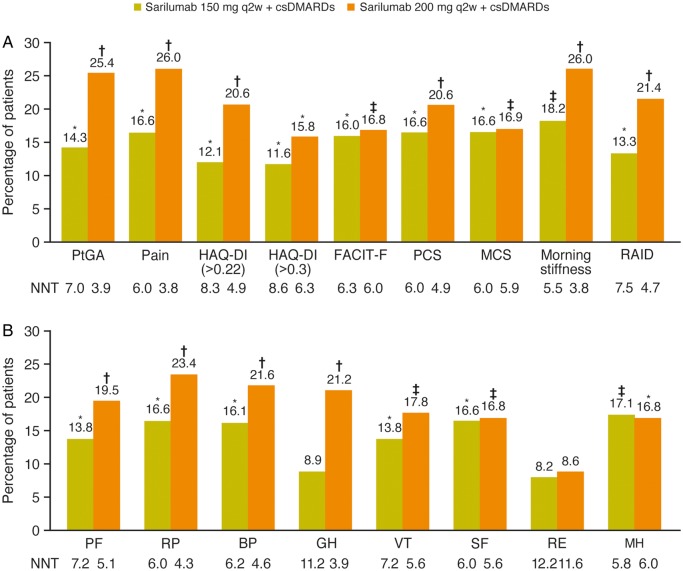

Figure 3.

Post hoc analysis of differences from placebo in the percentage of patients reporting improvements ≥MCID at week 24. (A) Patient global assessment (PtGA), Pain visual analogue scale, FACIT-Fatigue (FACIT-F), Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI), SF-36 physical and mental component scores (PCS and MCS), morning stiffness visual analogue scale and Rheumatoid Arthritis Impact of Disease (RAID). (B) SF-36 individual domains. *p<0.05 for the response rate relative to placebo. †p<0.0001 for the response rate relative to placebo. ‡p<0.001 for the response rate relative to placebo. BP, Bodily Pain; csDMARDs, conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; GH, General Health perceptions; MH, Mental Health; NNT, number needed to treat; PF, Physical Functioning; RE, Role Emotional; RP, Role Physical; SF, Social Functioning; VT, Vitality.

Responder analyses

In prespecifed analysis of HAQ-DI and post hoc analyses of other PROs, percentages of patients who reported improvements ≥MCID (ie, the proportion of responders) were higher with both doses of sarilumab versus placebo across all PROs (p<0.05; figure 3A). Additionally, more patients receiving sarilumab reported values ≥MCID in individual SF-36 domains with exception of GH for the 150 mg dose and RE for both doses (figure 3B). These resulted in NNTs ranging from 3.8 (sarilumab 200 mg for pain) to 12.2 (sarilumab 150 mg for RE; figure 3). In the subgroup of ACR20 responders (n=274; 50.2% of the total population), the majority of patients reported improvements ≥MCID across PROs (range, 52.5–98.2%; data not shown).

The percentages of patients who reported normative values at baseline in FACIT-F and SF-36 domains ranged from <1% for BP to 22.1% for VT (see online supplementary figure S2A). At week 24 (see online supplementary figure S2B), the percentages of patients reporting scores ≥normative values across FACIT-F and individual SF-36 domains increased with both doses of sarilumab (ranging from 14.9% for RP to 50.5% for VT) with greater increases compared with placebo (p<0.05 for both sarilumab doses for PF and 200 mg for BP).

Correlation analyses

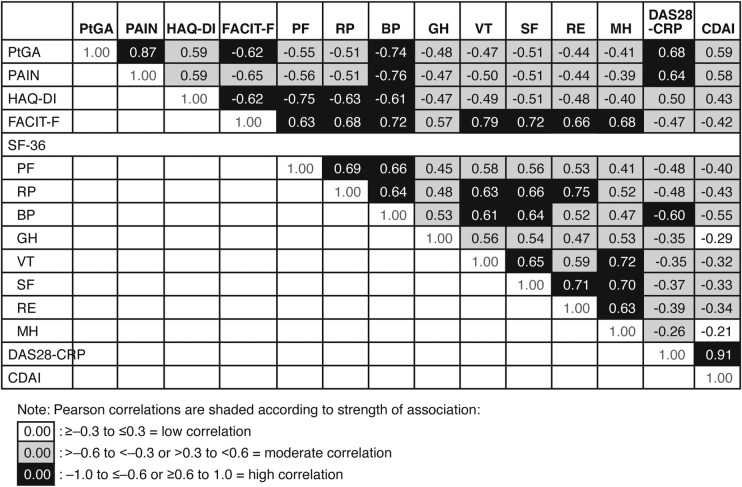

There were moderate correlations between individual PROs and clinical measures of disease activity (DAS28-CRP and CDAI) at week 24, with the exception of strong correlations between pain, PtGA and the BP domain of SF-36 with DAS28-CRP, and low correlations between SF-36 domains GH with CDAI and MH with DAS28-CRP and CDAI (figure 4). The majority of correlations between individual PROs and SF-36 domains were moderate; the strongest were between those that measure similar constructs: FACIT-F with VT (r=0.79), HAQ-DI with PF (r=−0.75) and VAS pain with BP (r=−0.76). There was also a strong correlation between PtGA and pain VAS (r=0.87).

Figure 4.

Correlations between observed patient-reported outcomes and disease activity scores at week 24. Positive correlations indicate similar directionality of scales; negative correlations indicate opposing directionality. BP, Bodily Pain; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; DAS28-CRP, 28-joint Disease Activity using C reactive protein; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue scale; GH, General Health perceptions; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; MH, Mental Health; PF, Physical Functioning; PtGA, patient global assessment of disease activity; RE, Role Emotional; RP, Role Physical; SF-36, Short Form 36 Health Survey V.2. SF, Social Functioning; VT, Vitality.

Discussion

In addition to clinical data, a patient's perception of their disease impact is an important consideration when making treatment decisions. These analyses from the TARGET RCT complements the clinical efficacy and safety data previously reported,14 and demonstrates that treatment with sarilumab + csDMARDs resulted in patient-reported benefits that were clinically meaningful in pain, fatigue, function, participation and health status. In TARGET, consistently greater improvements were reported by patients who received sarilumab compared with those who received placebo, with dose-dependent benefits favouring 200 mg; favourable results observed at week 12 were maintained at week 24. These results are similar to patient-reported benefits in MOBILITY,13 which evaluated sarilumab plus MTX in patients with MTX-IR. Notably, reported improvements at week 24 in TARGET were comparable to those in MOBILITY for those PROs evaluated in both RCTs, despite higher baseline disease activity among patients with TNF-IR enrolled in TARGET.

Fatigue, which along with pain may be mediated by IL-6, the target of sarilumab,11 12 remains a persistent problem31 and is reported to be of greater concern to patients than tender and swollen joints.7 32 Improvements in fatigue were reported in TARGET based on FACIT-F, supported by changes in the conceptually similar SF-36 VT domain as well as one of the domains of RAID, a disease-specific composite measure that assesses the impact of RA on domains of greatest importance to patients. RAID was not included in MOBILITY, and indeed, has not been used in many previous RA RCTs. Its inclusion in TARGET provided further support for the broad benefits of sarilumab improving the lives of patients with RA.

Another disease-specific measure included in TARGET was the WPS-RA, which demonstrated that RA interference with work within and outside the home was reduced with sarilumab, recognising that the proportion of patients working outside the home was low. Patients additionally reported reductions in the number of days missed of family, social or leisure activities. Such an impact on work within the home as well as participation in other activities has infrequently been captured in RA clinical trials. These observations indicate that in addition to the improvements in physical function reported by other measures (eg, HAQ-DI and SF-36 PF and RP domains), there are also direct patient-reported benefits in the ability to participate in work, family and social/leisure activities.

Post hoc analyses consistently indicated that a higher proportion of patients reported improvements ≥MCID with sarilumab compared with placebo (p<0.05), indicating that mean changes from baseline translated into clinically meaningful benefits on an individual patient level. Estimates of NNTs indicated that, with few exceptions, between four and nine patients would need to be treated to achieve these levels of benefit. Additionally, the proportion of patients who reported normative values in SF-36 and FACIT was higher with sarilumab than placebo. Normative values represent a level of response commensurate with individuals without arthritis or other chronic conditions, previously not expected in RA RCTs.

Consistent with prior research,13 26 strong correlations were observed for conceptually related domains, including FACIT-F with SF-36 VT, HAQ-DI with SF-36 PF and SF-36 BP with pain VAS. Strong correlations were evident for patient global scores with pain VAS and FACIT-F at week 24, supporting the importance of pain and fatigue to patients' overall perception of their disease activity.33 Moderate correlations were evident between other PROs, and between most PROs and clinical measures of disease activity (DAS28-CRP and CDAI), supporting the concept that multiple PROs reflect different domains of response from clinical measures and from each other. These findings indicate the importance of a full range of PRO measures to comprehensively assess treatment benefit.

Strengths and limitations

A main strength of this trial was the use of PROs covering a wide range of symptoms and impact of RA, including disease-specific and generic measures to comprehensively evaluate patients' perspectives and to place them in the context of the general population. Another is inclusion of the WPS-RA, which captures household work productivity as well as participation in family/social and leisure activities that are overlooked in other productivity measures. A limitation of WPS-RA may be that it underestimates presenteeism,34 since it only assesses days with ≥50% lost productivity. Further, the use of hierarchical testing procedures limited the ability to interpret some of the PRO data with regard to claims of statistical significance. One limitation of the analysis of the proportion of patients reporting scores ≥ normative values is that we used US population norms. Normative data for SF-36 are not available for all countries, but for those that are available are generally close to US norms. As a benchmark comparison, US norms should give a reasonable idea of the proportion of patients reporting values in the range that would be expected in the general population.

In conclusion, the multicentre TARGET RCT demonstrated patient-reported benefits with sarilumab across a range of PROs that were consistent with those in the MOBILITY trial, but in a more difficult-to-treat population. These findings demonstrate that targeting IL-6 with sarilumab represents an appropriate and effective management strategy in these patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be submitted for publication. VS had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The study was conceptualised and designed by VS, RF, NMHG, HvH and YL. HvH, YL, CP-T and RF acquired the data. VS, MR, CIC, CWJP, SG, DB, EM, NMHG, HvH, YL, CP-T and RF analysed and interpreted the data. All authors were involved in the study design and/or in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All authors approved the manuscript for submission.

Funding: This study was sponsored by Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. E. Jay Bienen, PhD, provided writing support funded by Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

Competing interests: VS has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Celltrion, Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America (CORRONA), Crescendo Bioscience, Eli Lilly, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Hospira, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi and UCB. MR, CWJP, SG, HvH, DB and YL are employees of Sanofi Genzyme and may hold stock and/or stock options in the company. CIC, EM and NMHG are employees of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and may hold stock and/or stock options in the company. CP-T has been principal investigator for Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MS, Vertex, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, Novo Nordisk and AbbVie and has received speaker fees from Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, UCB, Janssen and MSD. RF has received research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Ardea, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi Aventis and UCB; and has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Akros, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Roche and UCB.

Ethics approval: This RCT received approval from the Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee of the investigational centres.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kirwan JR, Hewlett SE, Heiberg T et al. Incorporating the patient perspective into outcome assessment in rheumatoid arthritis—progress at OMERACT 7. J Rheumatol 2005;32:2250–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirwan JR, Tugwell PS. Overview of the patient perspective at OMERACT 10—conceptualizing methods for developing patient-reported outcomes. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1699–701. 10.3899/jrheum.110388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use, European Medicines Agency. Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products other than NSAIDs for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis 2015. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2015/06/WC500187583.pdf (accessed 14 Nov 2016).

- 4.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. The Committee on Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials. Arthritis Rheum 1993;36:729–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahlmen M, Nordenskiold U, Archenholtz B et al. Rheumatology outcomes: the patient's perspective. A multicentre focus group interview study of Swedish rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:105–10. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strand V, Khanna D. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis and treatment on patients’ lives. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2010;28:S32–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rendas-Baum R, Bayliss M, Kosinski M et al. Measuring the effect of therapy in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials from the patient's perspective. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:1391–403. 10.1185/03007995.2014.896328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matcham F, Scott IC, Rayner L et al. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality-of-life assessed using the SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014;44:123–30. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potocky T, Rafique A, Fairhurst J et al. Evaluation of the binding kinetics and functional bioassay activity of sarilumab and tocilizumab to the human il-6 receptor alpha (il-6rα) [abstract]. Mod Rheumatol 2016;26(Suppl):S69–70. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srirangan S, Choy EH. The role of interleukin 6 in the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2010;2:247–56. 10.1177/1759720X10378372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaible HG. Nociceptive neurons detect cytokines in arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:470 10.1186/s13075-014-0470-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohleder N, Aringer M, Boentert M. Role of interleukin-6 in stress, sleep, and fatigue. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1261:88–96. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06634.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strand V, Kosinski M, Chen CI et al. Sarilumab plus methotrexate improves patient-reported outcomes in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate responses to methotrexate: results of a phase III study. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:198 10.1186/s13075-016-1096-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleischmann R, van Adelsberg J, Lin SL et al. Sarilumab and Nonbiologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs in Patients With Active Rheumatoid Arthritis and Inadequate Response or Intolerance to Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors. Arthritis Rheum. 2017;69:277–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:2569–81. 10.1002/art.27584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB et al. User's manual for the SF-36v2™ health survey, 2nd edn Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cella D, Yount S, Sorensen M et al. Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Scale relative to other instrumentation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005;32:811–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osterhaus JT, Purcaru O, Richard L. Discriminant validity, responsiveness and reliability of the rheumatoid arthritis-specific Work Productivity Survey (WPS-RA). Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R73 10.1186/ar2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gossec L, Paternotte S, Aanerud GJ et al. Finalisation and validation of the rheumatoid arthritis impact of disease score, a patient-derived composite measure of impact of rheumatoid arthritis: a EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:935–42. 10.1136/ard.2010.142901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vliet Vlieland TP, Zwinderman AH, Breedveld FC et al. Measurement of morning stiffness in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:757–63. 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00051-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Brien PC. Procedures for comparing samples with multiple endpoints. Biometrics 1984;40:1079–87. 10.2307/2531158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells GA, Tugwell P, Kraag GR et al. Minimum important difference between patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the patient's perspective. J Rheumatol 1993;20:557–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strand V, Boers M, Idzerda L et al. It's good to feel better but it's better to feel good and even better to feel good as soon as possible for as long as possible. Response criteria and the importance of change at OMERACT 10. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1720–7. 10.3899/jrheum.110392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schiff M, Weinblatt ME, Valente R et al. Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: two-year efficacy and safety findings from AMPLE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:86–94. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kremer JM, Blanco R, Brzosko M et al. Tocilizumab inhibits structural joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate responses to methotrexate: results from the double-blind treatment phase of a randomized placebo-controlled trial of tocilizumab safety and prevention of structural joint damage at one year. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:609–21. 10.1002/art.30158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strand V, Smolen JS, van Vollenhoven RF et al. Certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate provides broad relief from the burden of rheumatoid arthritis: analysis of patient-reported outcomes from the RAPID 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:996–1002. 10.1136/ard.2010.143586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008;9:105–21. 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lubeck DP. Patient-reported outcomes and their role in the assessment of rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacoeconomics 2004;22:27–38. 10.2165/00019053-200422001-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dougados M, Brault Y, Logeart I et al. Defining cut-off values for disease activity states and improvement scores for patient-reported outcomes: the example of the Rheumatoid Arthritis Impact of Disease (RAID). Arthritis Res Ther 2012;14:R129 10.1186/ar3859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osiri M, Suarez-Almazor ME, Wells GA et al. Number needed to treat (NNT): implication in rheumatology clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:316–21. 10.1136/ard.62.4.316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Steenbergen HW, Tsonaka R, Huizinga TW et al. Fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis; a persistent problem: a large longitudinal study. RMD Open 2015;1:e000041 10.1136/rmdopen-2014-000041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hewlett S, Carr M, Ryan S et al. Outcomes generated by patients with rheumatoid arthritis: how important are they? Musculoskeletal Care 2005;3:131–42. 10.1002/msc.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikolaus S, Bode C, Taal E et al. Fatigue and factors related to fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:1128–46. 10.1002/acr.21949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang K, Beaton DE, Boonen A et al. Measures of work disability and productivity: Rheumatoid Arthritis Specific Work Productivity Survey (WPS-RA), Workplace Activity Limitations Scale (WALS), Work Instability Scale for Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA-WIS), Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ), and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl 11):S337–49 10.1002/acr.20633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2016-000416supp_figures.pdf (355.1KB, pdf)