Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to assess surgical availability and readiness in 8 African countries using the WHO's Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA) tool.

Setting

We analysed data for surgical services, including basic and comprehensive surgery, comprehensive obstetric care, blood transfusion, and infection prevention, obtained from the WHO's SARA surveys in Sierra Leone, Uganda, Mauritania, Benin, Zambia, Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo and Togo.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Among the facilities that were expected to offer surgical services (N=3492), there were wide disparities between the countries in the number of facilities per 100 000 population that reported offering basic surgery (1.0–12.1), comprehensive surgery (0.1–0.8), comprehensive obstetric care (0.1–0.8) and blood transfusion (0.1–0.8). Only 0.1–0.3 facilities per 100 000 population had all three bellwether procedures available, namely laparotomy, open fracture management and caesarean section. In all the countries, the facilities that reported offering surgical services generally had a shortage of the necessary items for offering the services and this varied greatly between the countries, with the facilities having on average 27–53% of the items necessary for offering basic surgery, 56–83% for comprehensive surgery, 49–72% for comprehensive obstetric care and 54–80% for blood transfusion. Furthermore, few facilities had all the necessary items present. However, facilities that reported offering surgical services had on average most of the necessary items for the prevention of infection.

Conclusions

There are important gaps in the surgical services in the 8 African countries surveyed. Efforts are therefore urgently needed to address deficiencies in the availability and readiness to deliver surgical services in these nations, and this will require commitment from multiple stakeholders. SARA may be used to monitor availability and readiness at regular intervals, which will enable stakeholders to evaluate progress and identify gaps and areas for improvement.

Keywords: Africa, Surgical services, Deficiencies, SARA

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study involved a randomly selected sample of 2386 health facilities from eight African countries.

Statistically appropriate sampling methods and adjustments were made for the survey design to make the findings nationally representative.

The availability of basic surgery was calculated using the total number of health facilities as a denominator and not every facility sampled may have been expected to offer surgical care.

We cannot determine the optimal number of facilities offering surgical care per 100 000 population, as this number will be determined at the country level.

Availability and readiness are prerequisites for quality, and additional indicators will be required to evaluate the effectiveness, safety and timeliness of service delivery.

Introduction

The world's burden of surgical diseases is substantial and is increasing,1–5 and there are enormous gaps in access to surgical care, especially for the rural and marginalised segments of the population in Africa.6–18 While the underlying causes for disparities in access to health services are complex and contextual, barriers may include spatial accessibility, affordability, acceptability (cultural, religious and/or other factors), availability and quality.19–22

Previous studies using a Situational Analysis Tool (SAT)23 developed by members of the WHO's Global Initiative for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care have documented gross deficiencies in the availability of surgical services in a convenience sample of 505 health facilities in selected low income and middle income countries (LMICs),9–16 24–27 focusing on infrastructure, equipment and supplies, human resources, and the availability of selected interventions. Deficiencies were most pronounced at the primary referral level. For example, a regular supply of oxygen was available at only 4–78% of facilities, and an anaesthesia machine was present at only 24–71% of facilities. Caesarean section was performed at as few as 44% of facilities depending on the country, 30% for closed treatment of fractures and 41% for laparotomy.9–16 24–27 Similar findings were noted in a study concerning musculoskeletal surgical services at 883 health facilities in 24 LMICs.28

A number of barriers must be overcome to improve surgical service delivery, especially at the district hospital level in LMICs, to achieve universal access to essential surgical services. Efforts to enhance service delivery must include a strategy for monitoring the availability and readiness to deliver surgical care, as well as surgical output, quality and outcomes. The Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA) is a facilities-based assessment and monitoring tool which evaluates whether (1) facilities offer a variety of preventive and curative health services (availability), and if so, (2) whether they have the items required to deliver that service at the time of the site visit (readiness).29–34 To date SARA has been integrated within the health information systems of more than 20 countries. The goal of this retrospective review is to evaluate surgical availability and readiness in eight African countries, namely Sierra Leone, Uganda, Mauritania, Benin, Zambia, Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo and Togo.

Methods

This study used the SARA survey data for surgical services that are available at the WHO. The concept of SARA was developed by WHO and collaborating partners to assess whether a health facility meets the required conditions to support the provision of basic or specific services.29–34 Service availability refers to the physical presence of the delivery of services, while readiness refers to the ability of health facilities to deliver a service as measured through the physical presence of selected or ‘tracer’ items within the domains of trained staff, guidelines, equipment, laboratory services and medicines at the time of the site visit.

Countries conduct SARA nearly every 2 years though a few do it annually as per the WHO recommendations and some experience delay due to various reasons. Facilities are sampled through a single stage stratified random sampling method designed to give a representative national sample. Data are collected through structured key-informant interviews using a standard SARA core questionnaire that countries typical adopt although with adaptations to certain context-specific elements such as facility classifications, staff categories and national guidelines and policies. The SARA core questionnaire is a validated tool that focuses on key health services and the ability or readiness of facilities to offer the services. The questionnaire does not attempt to measure the quality of services or resources, but it can be used in conjunction with additional modules such as management assessment or quality of care.

SARA data are collected by trained data collectors using both paper questionnaires and mobile electronic devices that have CSPro software. Typically, data are collected to assess the availability of some specific services, general service-readiness and service-specific readiness. General-service readiness refers to the overall capacity of health facilities to provide general health services—as measured by the availability of components such as basic amenities, basic equipment, standard precautions for infection prevention, diagnostic capacity and essential medicines. Service-specific readiness meanwhile refers to the presence of items that are particularly important for offering a specific service, such as surgical care. Global positioning system devices are also used to record coordinates for each facility to facilitate mapping.

Where countries had cleaned primary data available with WHO, analysis was carried out in STATA V.11.0 using methods that are appropriate for the survey design used in the country. Details of the analysis are as follows. Each variable was assigned value 1 if the service or item for offering the service was available and 0 if they were unavailable. Answers which were reported by the participants as ‘don't know’ were summarised with n (%), but then treated as missing data. Sampling weights were then applied to reflect the probability of selection at each stage of the sampling design. The Stata commands for survey data were used for all analyses. Categorical variables were summarised as frequencies, proportions and 95% CIs. Continuous variables were summarised by the mean and 95% CIs. Where categorical variables had some categories with low frequency, categories were combined for analysis where appropriate.

The availability of basic surgical services was estimated among all facilities while that for comprehensive surgery, comprehensive obstetric care and blood transfusion services was calculated among facilities that were ‘expected’ to offer surgical services—hospitals in most countries (table 1, figures 1–4).

Table 1.

Number of facilities that reported offering surgical services per 100 000 population

| Benin 2013 | Burkina Faso 2013 | DRC 2013 | Mauritania 2013 | Sierra Leone 2013 | Togo 2012 | Uganda 2013 | Zambia 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic surgical services (calculated among all facilities) | ||||||||

| Basic surgery | 8.7 | 10.1 | 1.0 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 3.5 | 7.1 | 12.1 |

| Incision and drainage | 8.1 | 9.4 | 1.0 | 7.5 | 10.6 | 3.5 | 6.7 | 11.4 |

| Wound debridement | 7.6 | 8.9 | 0.9 | 9.4 | 7.3 | 3.5 | 5.3 | 8.0 |

| Acute burn management | 4.9 | 8.2 | 0.8 | 3.5 | 8.9 | 1.3 | 3.8 | 8.6 |

| Suturing | 8.3 | 9.9 | 1.0 | 10.0 | 11.0 | 3.5 | 6.8 | 12.0 |

| Closed fracture management | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| Cricothyrodoitomy | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Male circumcision | 4.8 | 9.1 | 0.9 | 8.3 | 6.8 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 0.9 |

| Hydrocoelectomy | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.7 |

| Chest tube insertion | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Tracheostomy | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Comprehensive surgical services (calculated among facilities expected to offer service) | ||||||||

| Comprehensive surgery | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| Tracheostomy | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Tubal ligation | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Vasectomy | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Dilation and curettage | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Obstetric fistula repair | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Episiotomy | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Appendectomy | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Hernia repair | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Cystotomy | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Urethral stricture dilation | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Laparotomy | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| Congenital hernia repair | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Neonatal surgery | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Cleft lip repair | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Contracture release | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Skin grafting | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Open fracture management | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Amputation | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Cataract surgery | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Comprehensive obstetric care (calculated among facilities expected to offer the service) | ||||||||

| Comprehensive obstetric care | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| Caesarean section | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Blood transfusion | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Comprehensive emergency obstetric care | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Blood transfusion services | ||||||||

| Offered blood transfusion services | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Emergency bellwether services | ||||||||

| Laparotomy | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| Open fracture management | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Caesarean section | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Had all three services | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

The availability of basic surgical services was estimated among all facilities while that for comprehensive surgery, comprehensive obstetric care and blood transfusion services was calculated among facilities that were expected to offer the services. Surgical services are listed as basic, comprehensive, comprehensive obstetric care, blood transfusion services and emergency bellwether procedures (laparotomy, open fracture management and caesarean section).

Figure 1.

Number of facilities that reported offering basic surgical services per 100 000 people.

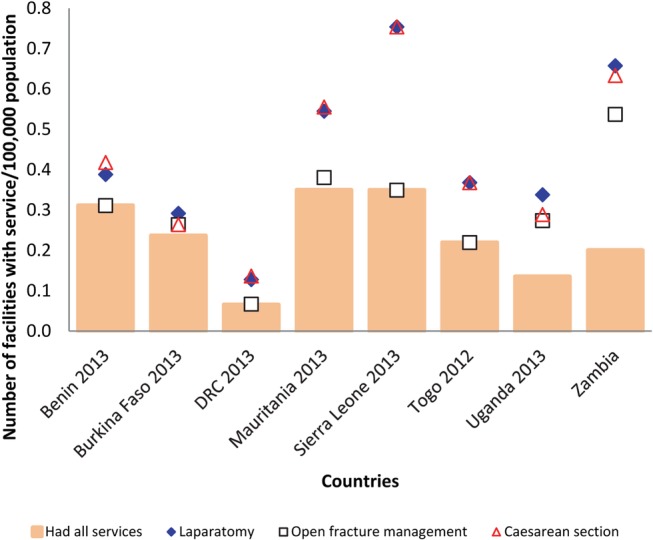

Figure 2.

Number of facilities that reported offering comprehensive surgery per 100 000 people.

Figure 3.

Number of facilities that reported offering comprehensive obstetric care per 100 000 people.

Figure 4.

Number of facilities that reported offering signal emergency services (Bellwether procedures) per 100 000 people.

The proportion of facilities that reported they offered each of the services was calculated together with 95% CI overall, and then by facility level, ownership and rural/urban location. Combining the information on the total population, total number of facilities and proportion offering surgical services, the number of facilities offering surgical services per 100 000 population was then calculated.

Readiness to offer services was assessed based on the presence of items that are particularly important for offering the services, called ‘tracer items’ (table 2, figures 5–8).

Table 2.

The percentage of facilities with tracer items and the readiness score (Mean % of items)

| Benin 2013 | Burkina Faso 2013 | DRC 2012 | Mauritania 2013 | Sierra Leone 2013 | Togo 2012 | Uganda 2013 | Zambia 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic surgical services (calculated among facilities that reported offering the services) | ||||||||

| Guidelines for IMEESC | 4 | 11 | 23 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 21 | 13 |

| At least one trained staff (IMEESC) | 1 | 5 | 15 | 4 | 14 | 4 | 25 | 6 |

| Needle holder | 66 | 70 | 81 | 51 | 71 | 43 | 87 | 79 |

| Scalpel handle with blade | 50 | 60 | 74 | 35 | 52 | 45 | 78 | 54 |

| Retractor | 13 | 23 | 57 | 21 | 15 | 17 | 35 | 26 |

| Surgical scissors | 70 | 76 | 76 | 50 | 80 | 45 | 79 | 70 |

| Nasogastric tubes | 24 | 22 | 44 | 18 | 58 | 18 | 41 | 22 |

| Tourniquet | 63 | 49 | 81 | 35 | 71 | 83 | 52 | 38 |

| Adult and paediatric resuscitators | 5 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 13 | 19 | 30 |

| Suction apparatus | 36 | 25 | 38 | 18 | 69 | 18 | 30 | 46 |

| Oxygen | 24 | 8 | 15 | 16 | 10 | 19 | 31 | 28 |

| Skin disinfectant | 89 | 95 | 71 | 74 | 86 | 57 | 100 | 88 |

| Sutures | 24 | 23 | 17 | 11 | 51 | 7 | 70 | 83 |

| Ketamine (injectable) | 13 | 17 | 58 | 19 | 11 | 14 | 40 | 15 |

| Lidocaine | 65 | 76 | 65 | 40 | 93 | 39 | 90 | |

| Had all the items | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 |

| Readiness score | 37 | 38 | 48 | 27 | 46 | 29 | 53 | 43 |

| Comprehensive surgical services (calculated among facilities that reported offering the service) | ||||||||

| Guidelines for IMEESC | 18 | 64 | 41 | 40 | 35 | 44 | 30 | 14 |

| At least one trained staff (IMEESC) | 7 | 55 | 23 | 24 | 37 | 32 | 40 | 14 |

| Staff trained in surgery | 80 | 95 | 81 | 70 | 82 | 76 | 93 | |

| Staff trained in anaesthesia | 89 | 95 | 58 | 69 | 89 | 71 | 88 | |

| Anaesthesia equipment | 18 | 36 | 15 | 35 | 10 | 11 | 32 | 75 |

| Spinal needle | 93 | 91 | 78 | 69 | 63 | 81 | 90 | |

| Suction apparatus | 95 | 100 | 72 | 91 | 79 | 78 | 100 | 92 |

| Oxygen | 91 | 82 | 46 | 84 | 74 | 81 | 97 | 95 |

| Thiopental (powder) | 100 | 100 | 89 | 77 | 44 | 86 | 67 | |

| Suxamethonium bromide | 91 | 77 | 84 | 62 | 28 | 67 | 55 | |

| Atropine | 98 | 100 | 24 | 75 | 72 | 86 | 100 | |

| Diazepam (injectable) | 100 | 91 | 92 | 80 | 79 | 100 | 100 | |

| Halothane (inhalation) | 86 | 82 | 90 | 60 | 40 | 25 | 71 | 73 |

| Bupivacaine (injectable) | 98 | 86 | 93 | 63 | 54 | 76 | 78 | |

| Lidocaine 5% (heavy spinal) | 95 | 82 | 18 | 56 | 52 | 95 | 80 | 78 |

| Epinephrine (Injectable) | 89 | 91 | 55 | 65 | 58 | 67 | 97 | |

| Ephedrine (injectable) | 93 | 91 | 42 | 55 | 60 | 76 | 83 | |

| Had all items | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 12 | 5 |

| Readiness score | 79 | 83 | 58 | 63 | 56 | 68 | 77 | 63 |

| Comprehensive obstetric care (calculated among facilities that reported offering the service) | ||||||||

| Guidelines available CEmOC | 65 | 95 | 51 | 84 | 53 | 82 | 67 | 38 |

| At least 1 trained staff CEmOC | 37 | 89 | 40 | 74 | 42 | 29 | 77 | 35 |

| Staff trained in surgery | 93 | 95 | 98 | 100 | 89 | 94 | 99 | |

| Staff trained in anaesthesia | 93 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 97 | 88 | 100 | |

| Anaesthesia equipment | 18 | 37 | 15 | 47 | 10 | 14 | 35 | 41 |

| Incubator | 32 | 26 | 19 | 35 | 54 | 59 | 62 | 74 |

| Blood typing | 77 | 84 | 82 | 75 | 60 | 94 | 91 | 94 |

| Cross match testing | 84 | 53 | 26 | 43 | 35 | 67 | 74 | 91 |

| Blood supply sufficiency | 37 | 47 | 47 | 20 | 53 | 22 | 17 | 38 |

| Blood supply safety | 47 | 95 | 67 | 31 | 82 | 88 | 86 | 97 |

| Had all items | 2 | 5 | 50 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Readiness score | 58 | 72 | 49 | 61 | 58 | 64 | 71 | 64 |

| Blood transfusion services (calculated among facilities that reported offering the service) | ||||||||

| Guidelines | 88 | 90 | 82 | 68 | 64 | 79 | 68 | 60 |

| Trained staff | 50 | 86 | 47 | 42 | 49 | 37 | 58 | 45 |

| Refrigerator | 91 | 90 | 62 | 68 | 78 | 85 | 100 | 81 |

| Blood typing | 81 | 90 | 82 | 74 | 66 | 90 | 88 | 62 |

| Cross-Matching | 85 | 57 | 30 | 37 | 43 | 60 | 72 | 58 |

| Blood sufficiency | 35 | 52 | 48 | 42 | 59 | 35 | 16 | 66 |

| Blood safety | 60 | 95 | 69 | 47 | 87 | 82 | 86 | 26 |

| Had all items | 9 | 14 | 9 | 0 | 14 | 3 | 8 | 11 |

| Readiness score | 70 | 80 | 60 | 54 | 64 | 67 | 70 | 57 |

Readiness for surgical services was assessed based on the presence of basic items that are particularly important for offering the services and the assessment was performed among facilities that reported offering the service. The service specific readiness score has been defined as the mean availability of service specific tracer items in four domains (staff and training, equipment, diagnostics, and medicine/commodities).

Figure 5.

Mean (%) of items for basic surgery and percentage facilities with all the items.

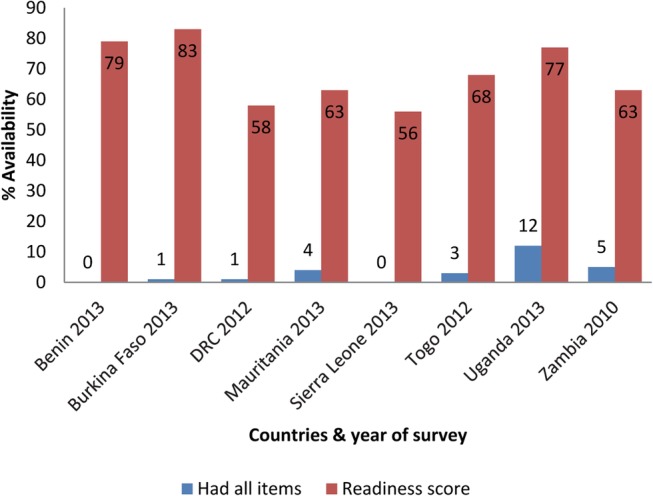

Figure 6.

Mean (%) of items for comprehensive surgery and percentage facilities with all the items.

Figure 7.

Mean (%) of items for comprehensive obstetric care and percentage facilities with all the items.

Figure 8.

Mean (%) of tracer items for blood transfusion and percentage facilities with all the items.

Assessment of readiness was performed among the facilities that reported offering the surgical services, and was calculated as the mean number of facilities which had each tracer item.

Results

This report used data for eight countries; however, primary data for the most recent SARA survey were available for seven of the eight countries reviewed, namely: Sierra Leone (2012, n=106 facilities), Uganda (2013, n=209 facilities), Mauritania (2013, n=232 facilities), Benin (2013, n=189 facilities), Burkina Faso (2013, n=686 facilities), Democratic Republic of Congo (2013, n=299 facilities) and Togo (2013, n=100 facilities). Primary data for Zambia were unavailable at WHO. Consequently, data from Zambia's SARA report on the availability and readiness for surgical services (2010, n=565 facilities) were included in the current report.

Availability of surgical services

A relatively high number of facilities reported offering basic surgery per 100 000 population, with Zambia having the highest, 12 times as high as DRC (table 1, figure 1). However, most of the countries had on average <1 facility offering tracheostomy, chest tube insertion, hydrocoelectomy, cricothyroidotomy and closed fracture management per 100 000 population. Less than one facility per 100 000 population reported offering comprehensive surgery, comprehensive obstetric care and blood transfusion services, with the numbers particularly low in Benin, Burkina Faso and DRC. These findings are similar to both comprehensive obstetric care and blood transfusion services (table 1). Assessment of the bellwether surgical procedures was based on the performance of laparotomy, open fracture management and caesarean section, and only 0.3 or less facilities reported offering all the three bellwether procedures per 100 000 population. Open fracture management was the least available service in most of the countries, ranging from 0.1 in DRC to 0.5 in Zambia per 100 000 population.

Readiness to deliver surgical services

Across most of the countries, the great majority of facilities that reported offering surgical services did not have all the basic items for offering the services. There were wide disparities between countries in the readiness scores (ie, mean availability of the basic items) for surgical services. The readiness score for basic surgery was highest in Uganda and lowest in Mauritania, with facilities having on average 53% and 27% of the basic items that were enquired about, respectively. The readiness score for comprehensive surgery was highest in Burkina Faso (83%) and lowest in Sierra Leone (56%). Across the countries generally, the readiness scores were lowest for basic surgery and highest for comprehensive surgery. Considering the individual items, guidelines and staff were the least available items across all the countries. Skin disinfectants and items for offering general anaesthesia were mostly available. Readiness scores for comprehensive obstetric care ranged from 49 to 72%, while 54–80% of facilities had all the basic items available for blood transfusion.

Infection control in facilities that offered surgical services

Items queried include safe final disposal of sharps and infectious wastes, appropriate storage of sharps and infectious wastes, disinfectant, syringes, latex gloves, soap and running water or alcohol-based hand rub and guidelines for standard precautions. In most of the countries, the great majority of the facilities that reported offering surgical services had the necessary items for infection control, with facilities offering comprehensive surgery having on average 82–94% of the items, Caesarean section 70–94% and those offering blood transfusion having on average 74–95% of the items (table 3).

Table 3.

Mean (%) of tracer items for infection control in facilities that offered surgical services

| Uganda 2013 N=209 | Sierra Leone 2012 N=106 | Benin 2013 N=189 | Burkina Faso 2013 N=686 | Mauritania 2013 N=232 | Zambia 2010 N=565 | DRC 2013 N=299 | Togo N=100 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic surgery | 84 | 80 | 77 | 85 | 57 | No data | 75 | 89 |

| Comprehensive surgery | 84 | 86 | 86 | 93 | 82 | 82 | 94 | |

| Caesarean section | 85 | 88 | 84 | 93 | 83 | 79 | 94 | |

| Blood transfusion | 87 | 85 | 77 | 92 | 74 | 79 | 95 |

The great majority of the facilities offering basic surgery also had the necessary items except Mauritania (57%).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess whether surgical services and the necessary but basic items for offering them were available in eight African countries, and the SARA surveys collect data on whether a health facility is delivering a particular service (availability), and whether the facility has selected ‘tracer’ items, including equipment, guidelines, medicines and staff, on the day of inspection (readiness). We identified large gaps in the availability and readiness for surgical services in all eight countries. This supports previous studies using the SAT tool in which deficiencies have been noted in infrastructure, equipment and supplies, human resources, and interventions offered.9–16 24–28 In contrast to studies using the SAT tool which reported a ‘snap shot’ at a single point in time from a convenience sample of health facilities, SARA uses sampling methodology. The link between expectations for service delivery and the availability of services is more explicit with readiness indicators, which also provide a more robust assessment of functionality since they are assessed by direct inspection during the site visit. SARA can also be used as a monitoring tool, which will be important as countries respond to the recent World Health Assembly resolution concerning “strengthening emergency and essential surgical services as a component of the universal health coverage”.35

First, in most countries, not all facilities that were expected to offer surgical services did so, for example, between 1 and 12 facilities offered basic surgery per 100 000 population. We would generally expect one facility to provide the service per 100 000 population. The availability of comprehensive surgery was more limited, between 0.1 and 0.8 per 100 000 population. Similar gaps were observed in the availability of comprehensive obstetric care and blood transfusion. A sizeable number of health facilities will need to have surgery integrated, or strengthened, within their scope of services delivered.

Second, there was generally a shortage of the basic items that are particularly important for offering basic and comprehensive surgery, comprehensive obstetric care, and blood transfusions in those facilities that offered the services. Very few facilities had all of the tracer items available. For example, facilities that reported offering ‘basic’ surgery had on average only 27–53% of the required items, and the greatest deficiencies were in the presence of trained staff and guidelines. A lack of human resources for basic surgery is especially evident, and shortage of these items may increase the potential for mismanaging patients that need surgical care.

Deficiencies in the availability of or readiness to deliver ‘basic’ surgical services are especially concerning, considering that a significant percentage of the population in many of the countries studied, especially in the more rural areas, may only be able to access a ‘district’ hospital or equivalent for their acute medical or surgical conditions. Considerable morbidity and mortality could be averted by providing basic surgical services, as accessing higher level health facilities may be impossible due to geography/topography, inadequate road infrastructure and/or the availability or costs of transportation. Additionally, many of the items and/or skills required for the delivery of basic surgery are required to treat a variety of acute medical conditions, injuries, complications of pregnancy, etc.

Reassuringly however, the basic items for infection control were generally available in facilities that reported offering surgical services. For example, those offering comprehensive surgery had on average 82–94% of the necessary items for infection prevention, versus 79–94% for caesarean section and 74–95% for blood transfusion. In contrast, only 57% of the items to prevent infection in basic surgery were present in Mauritania, versus 75–89% in the other countries.

There are several limitations to this study, including the small numbers of facilities surveyed. However, the countries used statistically appropriate sampling methods to select the facilities, and adjustments were made for the survey design during analysis to make the findings nationally representative. We recognise that the availability of basic surgery was calculated using the total number of health facilities as a denominator and thus not every facility sampled may have been expected to offer surgical care. We also recognise that we have not clearly defined the optimal number of facilities offering surgical care per 100 000 population, as this number will be determined at the country level and based on local disease burden, distribution of the population and variables related to geospatial access. Across many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, the basic surgical services that were enquired about are expected at hospitals and higher level primary care facilities. As per the WHO recommendation, a higher level primary care facility has a target population of about 100 000 people and a general hospital of about 500 000. This means that at the minimum, there should be a facility offering basic surgical services per 100 000 population in a developing country. This was the basis for our calculation. With regard to readiness, not much variability would be expected between the facilities as they were, by design, expected to offer similar amounts of surgical services. We also recognise that there were some missing data points from Zambia, which may have impacted comparisons across countries. Despite these limitations, we believe that the findings of this study are likely to be reasonably representative of the availability and readiness for surgical services in the countries surveyed. We also recognise that each country will need to define which interventions are offered at each health facility providing surgical care, and in the present study ‘basic’ versus ‘comprehensive’ was defined arbitrarily and should necessarily be redefined or adapted at the country level. We also recognise that availability and readiness may not necessarily correlate with the number and types of procedures performed (output), and it would have been useful to include data from surgical log books. Service availability and readiness are prerequisites for quality, and additional indicators will be required to evaluate and monitor the effectiveness, safety and timeliness of surgical service delivery.

In summary, we identified important gaps in the availability of surgical services and the items required to offer the services in the eight African countries surveyed. Efforts are therefore needed urgently to address these gaps and improve the availability of safe, timely and quality surgical care. Each country will need to define the optimal number of facilities offering surgical care relative to their population and its distribution, and surgical services should be strengthened in facilities that offer surgical care but exhibit deficiencies in readiness. The specific surgical interventions offered at different tiers of the system will also need to be defined at the policy level, with consideration given to scaling up selected surgical services at higher level primary care facilities to enable people residing in rural areas to access the services closer to their homes.

A number of barriers will need to be surmounted to reach the goal of universal access to at least basic surgical services in Africa. This will require a multi-disciplinary, multi-sectoral effort aimed at strengthening the core elements or building blocks within each health system, supported by decision makers and donors. One priority that has achieved considerable attention is training and retaining surgical providers and task shifting or task sharing has been and should be used to augment the surgical workforce. Surgical providers must be posted in areas where there are gaps, and should be appropriately remunerated. The findings of this study emphasise the importance of equipping the facilities, which will enable health providers to deliver the services and should increase the likelihood of retention. In addition to its use as a means to highlight gaps in surgical services delivery, SARA can contribute to strengthening surgical service delivery as a monitoring tool, as countries make plans to address gaps in surgical care in accordance with the World Health Assembly resolution concerning strengthening emergency and essential surgical care as a component of universal health coverage.35 It will also be important to perform contextually relevant research to assess the safety and quality of surgical service delivery at lower level facilities.

Footnotes

Contributors: DAS contributed to project design, data analysis and drafted the manuscript. KO responsible for project design, contributed to data analysis and critical revisions of the manuscript. BD collected and analysed the data, codrafted the manuscript. MNC contributed to project design and reviewed the manuscript, SH contributed to data collection and revision of the manuscript. PR contributed to data collection and revision of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: The authors include WHO staff, and the views expressed in this publication reflect their views and not necessarily that of WHO. One of the authors (DAS) has served as a consultant for the WHO.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L et al. . Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015;386:569–624. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiser TG, Haynes AB, Molina G et al. . Estimate of the global volume of surgery in 2012: an assessment supporting improved health outcomes. Lancet. 2015;385(Suppl 2):S11 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60806-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Debas HT, Donkor P, Gawande A et al. In: Jamison DT, Kruk ME, Mock CN, eds. Essential surgery: disease control priorities. 3rd edn (Vol 1). Washington DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, 2015:19–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rose J, Weiser TG, Hider P et al. . Estimated need for surgery worldwide based on prevalence of diseases: a modelling strategy for the WHO Global Health Estimate. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3(Suppl 2):S13–20. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70087-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alkire BC, Raykar NP, Shrime MG et al. . Global access to surgical care: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e316–23. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70115-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galukande M, von Schreeb J, Wladis A et al. . Essential surgery at the district hospital: a retrospective descriptive analysis in three African countries. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000243 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozgediz D, Galukande M, Mabweijano J et al. . The neglect of the global surgical workforce: experience and evidence from Uganda. World J Surg 2008;32:1208–15. 10.1007/s00268-008-9473-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luboga S, Macfarlane SB, von Schreeb J et al. . Bellagio Essential Surgery Group (BESG). Increasing access to surgical services in sub-Saharan Africa: priorities for national and international agencies recommended by the Bellagio Essential Surgery Group . PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000200 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kushner AL, Cherian MN, Noel LPJ et al. . Addressing the millennium development goals from a surgical perspective: deficiencies in the capacity to deliver safe surgery and anaesthesia in eight low and middle-income countries. Arch Surg 2010;145:154–60. 10.1001/archsurg.2009.263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choo S, Perry H, Hesse AA et al. . Assessment of capacity for surgery, obstetrics and anaesthesia in 17 Ghanaian hospitals using a WHO assessment tool. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:1109–15. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02589.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowman KG, Jovic G, Rangel S et al. . Pediatric emergency and essential surgical care in Zambian hospitals: a nationwide survey. J Pediatr Surgery 2013;48:1363–70. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iddriss A, Shivute N, Bickler SW et al. . Emergency, anaesthetic and essential surgical capacity in the Gambia. Bull World Health Organ 2011;89:565–72. 10.2471/BLT.11.086892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kingham TP, Kamara TB, Cherian MN et al. . Quantifying surgical capacity in Sierra Leone. A guide for improving surgical care. Arch Surg 2009;144:122–7. discussion 128 10.1001/archsurg.2008.540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petroze RT, Nzayisenga A, Rusanganwa V et al. . Comprehensive national analysis of emergency and essential surgical capacity in Rwanda. Br J Surg. 2012;99:436–43. 10.1002/bjs.7816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman LA, Clement PT, Cherian MN et al. . Implementing Liberia's poverty reduction strategy. An assessment of emergency and essential surgical care. Arch Surg 2011;146:35–9. 10.1001/archsurg.2010.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penoyar T, Cohen H, Kibatala P et al. . Emergency and surgery services of primary hospitals in the United Republic of Tanzania. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000369 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruk ME, Wladis A, Mbembati N et al. . Human resource and funding constraints for essential surgery in district hospitals in Africa: a retrospective cross-sectional survey. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000242 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozgediz D, Kijjambu S, Galukande M et al. . Africa's neglected surgical workforce crisis. Lancet. 2008;371:627–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60279-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grimes CE, Bowman KG, Dodgion CM et al. . Systematic review of barriers to surgical care in low-income and middle-income countries. World J Surg 2011;35:941–50. 10.1007/s00268-011-1010-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obrist B, Iteba N, Lengeler C et al. . Access to health care in contexts of livelihood insecurity: a framework for analysis and action. PLoS Med 2007;4:1584–8. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McIntyre D, Thiede M, Birch S. Access as a policy-relevant concept in low- and middle-income countries. Health Econ Policy Law 2009;4:179–93. 10.1017/S1744133109004836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irfan FB, Irfan BB, Spiegel DA. Barriers to accessing surgical care in Pakistan: healthcare barrier model and quantitative systematic review. J Surg Res 2012;176:84–94. 10.1016/j.jss.2011.07.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. Tool for Situational Analysis for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care. http://www.who.int/surgery/publications/QuickSitAnalysisEESCsurvey.pdf (accessed 18 Nov 2016).

- 24.Contini S, Taqdeer A, Cherian M et al. . Emergency and essential surgical services in Afghanistan: still a missing challenge. World J Surg 2010;34:473–9. 10.1007/s00268-010-0406-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Natuzzi ES, Kushner A, Jagilly R et al. . Surgical care in the Solomon Islands: a road map for universal surgical care delivery. World J Surg 2011;35:1183–93. 10.1007/s00268-011-1097-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spiegel DA, Choo S, Cherian M et al. . Quantifying surgical and anaesthetic availability at primary health facilities in Mongolia. World J Surg 2011;35:272–9. 10.1007/s00268-010-0904-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taira BR, Cherian MN, Yakandawala H et al. . Survey of emergency and surgical capacity in the conflict-affected regions of Sri Lanka. World J Surg 2010;34:428–32. 10.1007/s00268-009-0254-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiegel DA, Nduaguba A, Cherian MN et al. . Deficiencies in the availability of essential musculoskeletal surgical services at 883 health facilities in 24 low- and lower-middle-income countries. World J Surg. 2015;39:1421–32. 10.1007/s00268-015-2971-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA). http://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/sara_introduction/en/ (accessed 18 Nov 2016).

- 30.Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA). Reference manual. Version 2.2. World health Organization, Geneva, July 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/149025/1/WHO_HIS_HSI_2014.5_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 18 Nov 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Neill K, Takane M, Sheffel A et al. . Monitoring service delivery for universal health coverage: the Service Availability and Readiness Assessment. Bull World Health Org 2013;91:923–31. 10.2471/BLT.12.116798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.SARA reports for Sierra Leone, Zambia, Benin, Uganda and Burkina Faso. Available at http://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/sara_reports/en/ (accessed 18 Nov 2016).

- 33.World Health Organization. Service Availability Mapping (SAM). http://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/samintro/en/ (accessed 18 Nov 2016).

- 34.Health systems assessment approach: a how-to manual. Bethesda, MD, Health Systems 20/20; https://www.hfgproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/HSAA_Manual_Version_2_Sept_20121.pdf (accessed 18 Nov 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Assembly (WHA) Resolution 68.15). Strengthening emergency and essential surgical care as a component of universal health coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA68/A68_31-en.pdf (accessed 18 Nov 2016). [Google Scholar]