Abstract

Objectives

Exposure to family medicine (FM) can serve to promote students' interest in this field. This study aimed at identifying clerkship characteristics which decrease or increase students' interest in FM.

Design

This cross-sectional questionnaire study analysed students' clerkship evaluations between the years 2004 and 2014. Descriptive statistics were used to compare four predefined groups: (1) high interest in FM before and after the clerkship (Remained high), (2) poor interest before and after the clerkship (Remained low), (3) poor interest before the clerkship which improved (Increased) and (4) high interest before the clerkship which decreased (Decreased).

Setting

Students' evaluations of FM clerkships in the fourth of 6 years of medical school.

Participants

All questionnaires with complete answers on students' interest in FM and its change as a result of the clerkship (2382 of 3963; 60.1%). The students' mean age was 26 years (± 3.9), 62.7% (n=1505) were female.

Outcome measure

The outcome was a change in students' interest in FM after completing the clerkship.

Results

Interest in FM after the clerkship was as follows: 40.1% (n=954) Remained high, 5.5% (n=134) Remained low, 42.1% (n=1002) Increased and 12.3% (n=292) Decreased. Students with decreased interest had performed a below-average number of learning activities (4 vs 6 activities). A total of 45.9% (n=134 of 292) of the students with decreased interest reported that the difficulty of the challenge was inadequate for their educational level: 81.3% (n=109) felt underchallenged and 18.7% (n=25) overchallenged.

Conclusions

In more than 50% of cases, the clerkship changed the students' interest in FM. Those with decreased interest were more frequently underchallenged. We observed an increase in FM if at least six learning activities were trained. Our findings stress the importance of well-designed FM clerkships. There is a need for standardised educational strategies which enable teaching physicians to operationalise educational requirements.

Keywords: EDUCATION & TRAINING (see Medical Education & Training), GENERAL MEDICINE (see Internal Medicine), MEDICAL EDUCATION & TRAINING

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A sample size of 2382 questionnaires provided the basis for analysis.

The study addressed the students' perspective, while the teaching physicians' view was not included.

This cross-sectional anonymous survey did not allow for a long-term follow-up of students' actual career choices.

Introduction

The increasing shortage of family medicine (FM) physicians in many countries has led to discussions among politicians and academics on how to optimise the recruitment of future family physicians.1 This problem is an urgent one given the ageing and impending retirement of large numbers of FM physicians in many western countries.2–4 To increase the recruitment of physicians for FM, an early exposure of students to the field is recommended.5 6 A recent systematic review which addresses the impact of FM clerkships on undergraduate medical education supports this approach.7 Clerkships are highly valued by students, and are known to improve students' attitudes towards FM. Furthermore, they have the potential to influence students' intended careers and actual career choices in favour of FM. Nevertheless, it was also shown that positive effects do not necessarily persist over time and favourable final career decisions are not definitive.7

So far, the majority of research in this field has focused on the characteristics of students as related to career choice or concentrated on the impact of clerkships on various proxies of career choice. These proxies are subject to methodological variability, as some authors describe students' ultimate career decision, while others focus on their interest in FM in earlier phases of their decision-making process.8–11 In contrast, research on the characteristics of clerkships associated with favourable changes of students' attitudes toward FM is lacking. Yet, such information would be helpful for designing successful clerkships and for evaluating the quality of clerkship teaching. Unsystematic observations at our medical school indicate that the educational challenge presented by the clerkship is influencing students' interest in FM. Drawing on a 10-year collection of questionnaires, this study aimed at analysing students' clerkship evaluations to identify which aspects of a clerkship decrease or increase students' interest in FM.

Methods

This cross-sectional questionnaire study analysed students' evaluations of their FM clerkship. The mandatory 2-week clerkship was organised by the Institute for General Medicine, University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany, for students in their fourth of 6 years of medical school. Students were free to choose a practice from a network of 180 teaching practices located in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. During their clerkship, students accompany teaching physicians in their practice to train in FM under supervision. Students are requested to document their activities in a log book which outlines mandatory learning activities. Teaching physicians attend annual meetings addressing clerkship issues (eg, training of feedback). The clerkship is embedded in the clinical part of the medical curriculum which also includes courses on physical examination, seminars on evidence-based FM as well as training in other clinical fields, for example, internal medicine, surgery, neurology and psychiatry. Students have been evaluating the clerkship since 1995 using a self-administered, paper-based questionnaire. In this study, we analyse the questionnaires from 2004 to 2014. All students were asked to complete the anonymous questionnaire when handing in their clerkship reports. The total number of students who participated in the clerkship during these 10 years is unknown due to lack of data between 2004 and 2007. We estimated that ∼4200 students were enrolled between 2004 and 2014, which yields a response rate of 94.4%.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed by academic teachers of our institute in cooperation with a professor of teaching methodology. The development of the questionnaire followed scientific criteria, although no details were available from its piloting in 1994/1995. The semistandardised questionnaire consisted of 56 open, closed and semiclosed items (see online supplementary appendix for details). The present analysis included the following questions:

Interest in FM before and after the clerkship: ‘How interested in FM were you before the clerkship?’ and ‘How interested in FM are you after the clerkship?’(answer options: Likert scale from 1= very high to 5= very low);

Learning activities (multiple answers): (1) observing physician–patient interactions, (2) taking medical histories, (3) performing physical examinations, (4) discussing clinical cases, (5) developing therapeutic concepts, (6) drawing blood, (7) analysing ECGs, (8) using ultrasound, (9) managing wound care and (10) obtaining peripheral venous accesses;

Adequacy of the educational challenge: ‘On a professional level, how did you feel during the clerkship?’ (answer options: (1) over-challenged, (2) under-challenged and (3) adequately challenged);

Precision of teaching instructions: ‘How precise was the teaching?’ (answer options: Likert scale from 1= best to 5= worst score);

Personal relationship to teaching practitioner: ‘Did you perceive the teaching physician as friendly and empathic?’ and ‘Did you enjoy working with the practitioner?’(answer options: Likert scale from 1= best to 5= worst score);

Overall rating of the clerkship: ‘Which overall grade would you give the clerkship?’ (answer options: Likert scale from 1= very good to 5= inadequate).

bmjopen-2016-012794supp.pdf (4.2MB, pdf)

In addition, the following student and teaching practice characteristics were requested: current motivation for studying medicine (‘How high is your current motivation for studying medicine?’, answer options: Likert scale from 1= very high to 5= very low), individual characteristics (age, gender and prior vocational training in the medical field) and teaching practice characteristics (group/single practice).

Statistical analysis

Four groups were defined based on students' change of interest in FM: (1) high interest in FM before and after clerkship (Remained high), (2) poor interest before and after clerkship (Remained low), (3) poor interest before the clerkship which improved (Increased) and (4) high interest before the clerkship which decreased (Decreased). To identify factors associated with a change of students' interest in the field, clerkship, practice and students' characteristics were used to compare the four groups.

Answers on the five-point Likert scale were dichotomised into positive (1–3) and negative (4–5) ratings. The more neutral answer ‘3’ was assigned to the positive ratings. Also, the average number of learning activities performed during the clerkship was calculated and dichotomised using the median value of the total sample as cut-off (≤ 6/> 6 activities). Descriptive analyses were performed for the total sample and stratified by the four groups. We decided against multiple testing and, because of the high prevalence of positive ratings, did not calculate bivariate and multivariate models. All analyses were explorative and were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 22 (Armonk, New York, USA: IBM Corp.).

Results

Study population

Of the 3963 questionnaires available, 2382 (60.1%) showed complete answers on students' change of interest in FM. Students included in this analysis did not differ from those excluded with regard to gender and current motivation for studying medicine. However, students included were more likely to have prior vocational training in the medical field (25.3% vs 1.2%) and to be placed in a group practice (51.8% vs 34.8%).

Of the 2382 students, 62.7% (n=1490) were female and the mean age was 26 years (± 3.9 years; range 21–62). Interest in FM changed in 54.4% (n=1294) of students: it increased in 42.1% (n=1002) and decreased in 12.3% (n=292). The interest remained high in 40.1% (n=954) and low in 5.5% (n=134). The four groups did not differ with regard to students' characteristics. However, students in the groups Remained high (51.3%) and Increased (54.9%) were more often placed in group practices than those in the groups Remained low (46.2%) and Decreased (45.2%). See table 1 for details.

Table 1.

Students' characteristics: total sample and stratified by the change of interest in family medicine after the clerkship (n=2382)

| Total (n=2382) |

Remained high (n=954) |

Remained low (n=134) |

Increased (n=1002) |

Decreased (n=292) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| ≤ 26 years (missing data: 18) | 1596 | 67.5 | 644 | 68.2 | 101 | 76.5 | 649 | 65.2 | 202 | 69.2 |

| Female (missing data: 7) | 1490 | 62.7 | 594 | 62.5 | 80 | 60.2 | 620 | 62.0 | 196 | 67.1 |

| Prior vocational training in the medical field (missing data: 2) | 603 | 25.3 | 239 | 25.1 | 29 | 21.6 | 257 | 25.7 | 78 | 26.7 |

| High motivation for studying medicine (missing data: 12) | 2240 | 94.5 | 898 | 94.3 | 121 | 91.0 | 948 | 95.4 | 273 | 93.8 |

| Clerkship in group practice (missing data: 16) | 1225 | 51.8 | 485 | 51.3 | 61 | 46.2 | 548 | 54.9 | 131 | 45.2 |

FM, family medicine.

Learning activities during the clerkship

On average, students performed six of the 10 learning activities outlined in the log book. Only 2.0% (n=79) reported having performed all 10 activities. Students with increased interest (49.7%, n=497) and those whose interest remained high (55.2%, n=527) were more likely to have trained > 6 activities than those with decreased interest (22.0%, n=64) and those whose interest remained low (30.6%, n=41). Aiming at understanding which aspects of a clerkship are relevant for students' interest in FM, it is noteworthy that students in the group Decreased only practiced four activities on average (see table 2 for details).

Table 2.

Learning activities trained by students (n=2382)

| Total (n=2382) |

Remained high (n=954) |

Remained low (n=134) |

Increased (n=1002) |

Decreased (n=292) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Observed physician–patient interactions | 2291 | 96.2 | 926 | 97.1 | 132 | 98.5 | 951 | 95.0 | 282 | 96.6 |

| Performed physical examinations | 2047 | 85.9 | 831 | 87.1 | 109 | 81.3 | 907 | 90.5 | 200 | 68.5 |

| Took medical histories | 1942 | 81.6 | 792 | 83.0 | 98 | 73.1 | 875 | 87.3 | 177 | 60.8 |

| Discussed clinical cases | 1939 | 81.4 | 796 | 83.4 | 100 | 74.6 | 878 | 87.6 | 165 | 56.5 |

| Analysed ECGs | 1364 | 57.3 | 550 | 57.7 | 61 | 45.5 | 654 | 65.3 | 99 | 33.9 |

| Draw blood | 1336 | 56.1 | 555 | 58.2 | 65 | 48.5 | 576 | 57.5 | 140 | 47.9 |

| Used ultrasound | 1075 | 45.1 | 438 | 45.9 | 52 | 38.8 | 509 | 50.8 | 76 | 26.0 |

| Developed therapeutic concepts | 1008 | 42.3 | 429 | 45.0 | 45 | 33.6 | 472 | 47.1 | 62 | 21.2 |

| Managed wound care | 765 | 32.1 | 297 | 31.1 | 29 | 21.6 | 375 | 37.4 | 64 | 21.9 |

| Obtained peripheral venous access | 604 | 25.4 | 238 | 24.9 | 28 | 20.9 | 293 | 29.2 | 45 | 15.4 |

The three most frequently trained activities were: observing patient–physician interactions (96.2%, n=2291), performing physical examinations (85.9%, n=2047) and taking medical histories (81.6%, n=1942). In contrast, wound care, using ultrasound or obtaining peripheral venous accesses were performed by < 50% of students (table 2).

Students' assessment of the educational challenge presented by the clerkship

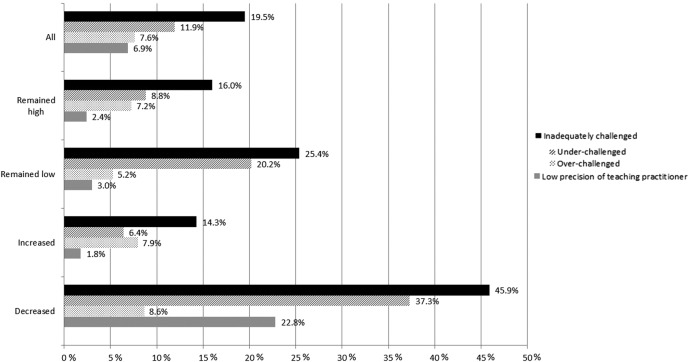

A total of 72.9% of the students (n=1736) felt adequately challenged during the clerkship, yet differences between groups were observed: 76.3% of the students whose interest remained high and 80.5% of those whose interest increased felt adequately challenged. In comparison, this was reported by 63.4% in the group Remained low and by 39.7% in Decreased. Interestingly, across all four groups, 19.5% of the students did not feel adequately challenged. This proportion was much higher among students with decreased interest (45.9%) than in the three remaining groups (Remained high: 16.0%, Remained low: 25.4% and Increased: 14.3%).

Overall, students were more likely to feel underchallenged than overchallenged (61.2% vs 38.8%). This was most pronounced in students with decreased interest: among these, 37.3% felt underchallenged and 8.6% felt overchallenged. The majority of students whose interest remained low and decreased felt underchallenged (Remained low: 79.4%, n=27 of 34; Decreased: 81.3%, n=109 of 134). See table 3 and figure 1 for details.

Table 3.

Students' assessment of the educational challenge presented by the clerkships

| |

Students per group |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequately challenged | Overchallenged | Underchallenged | |

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Total (n=2382) | 19.5 (464) | 7.6 (180) | 11.9 (284) |

| Subgroup analysis | |||

| Remained high (n=954) | 16.0 (153) | 7.2 (69) | 8.8 (84) |

| Remained low (n=134) | 25.4 (34) | 5.2 (7) | 20.2 (27) |

| Increased (n=1002) | 14.3 (143) | 7.9 (79) | 6.4 (64) |

| Decreased (n=292) | 45.9 (134) | 8.6 (25) | 37.3 (109) |

Figure 1.

Educational challenge stratified by the change of interest in FM.

Precision of teaching instructions

The vast majority of students were satisfied with the precision of the instructions given by their teaching physician (95.3%). A subanalysis of those who reported dissatisfaction showed marked differences between the four groups: while 22.8% of the students with decreased interest were dissatisfied with the precision of instructions, this was reported by a maximum of 3% of the students in the groups Remained high, Increased and Remained low.

Personal relationship with the teaching physicians

Almost all students (98.8%, n=2316) perceived the teaching physician as being friendly and empathic. Similarly, 96.4% (n=2286) enjoyed working with their teaching physician. It is noteworthy that – across the four groups – there were no associations between the personal relationship with the teaching physician and students' change of interest in FM. This indicates the importance of the educational content of the clerkship.

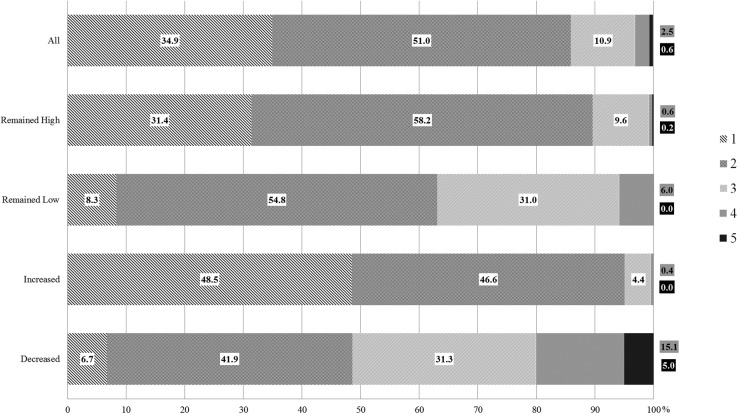

Students' overall rating of the clerkship

The mean rating of the clerkship was 1.8 (figure 2). Better ratings were given by students whose interest remained high and increased (1.8 and 1.6). In contrast, the groups Remained low and Decreased rated the clerkship nearly one score lower (2.4 and 2.7). A total of 20% of the students with decreased interest gave the worst ratings (4 and 5), compared with 6% of students whose interest remained low and < 1% in the two other groups.

Figure 2.

Overall rating of the clerkship (answer key: 1=very good to 5=inadequate).

Discussion

Aiming to identify clerkship characteristics which decrease or increase students' interest in FM, our study identified two characteristics of relevance: the number of activities trained and the adequacy of the educational challenge. These findings contribute to the current understanding that early exposure to FM is important for students’ future interest in the field. Our study calls for well-designed FM clerkships which allow students to train activities relevant to patient care using a predefined and standardised approach. The importance is all the greater given the fact that the clerkship actually changed the interest of more than half (54%) of the students. These results are relevant for all settings with a shortage of family physicians which consider clerkships as a strategy to raise students' interest in FM.

Important clerkship characteristics for promoting interest in family medicine

Despite a log book outlining required learning activities, only 4% of students trained all 10 activities. This suggests barriers, for example, in students, practices, teaching physicians or patients. Patient-student factors are unlikely to have been a barrier as prior studies have shown that patients look favourably on students' participation in teaching practices.12 Yet, other studies have identified discrepancies between the expectations of students, physicians and the curricula-based learning objectives as barriers.8 13 Our study shows that the number of activities performed is relevant and indicates that students prefer to be actively involved. Furthermore, our results emphasise the relevance of ensuring an adequate educational challenge: in students whose interest in FM decreased, almost two-thirds felt inadequately challenged, with a majority reporting that they feel underchallenged. This finding is supported by two other studies. A German study has shown that there were marked differences between practices with regard to students' learning opportunities and the performance of the teaching FM physicians as rated by students.14 At the University of Iowa, students who rated the educational value and quality of their clerkship as high or very high were 2.9 times more likely to choose a career in FM.15 Also, it is well known that an adequate level of challenge is a key determinant for successful learning in any learning environment.16 However, clerkships in FM practices pose a challenge for each medical school, at least in education systems where FM physicians volunteer as teaching physicians in their physician-owned practice. Although – as in our setting – they receive instructions in teaching methodology at least annually, the actual teaching scenario is something of a ‘black box’ for the medical schools, with only strong negative feedbacks leading to interventions (ie, change of a student's practice placement). Our study calls for new strategies to operationalise and standardise the educational responsibilities of teaching physicians.

Limitations

First, we faced missing data due to incomplete answers. Second, our study did not include the point of view of the teaching physicians and the teaching practices. Third, although the study was conducted in one university only, the results can likely be transferred to other academic facilities. Fourth, although interesting, this anonymous survey did not allow for a long-term follow-up on an individual basis. The strength of the study is the high number of participants and the lengthy 10-year time span. Furthermore, our findings are relevant for other academic settings which use clerkships to promote FM recruitment.

Conclusion

Our findings stress the importance of well-designed FM clerkships which allow for the training of clinical activities. There is a need for standardised educational strategies which enable teaching physicians to operationalise learning requirements in their practice setting. Further research is required to address subsequent issues of importance, for example, strategies on how to assess each student's educational level prior to the clerkship and how to identify barriers and facilitators for training of predefined learning activities.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dipl.-Ges.oec. Sabrina Reinders and Sandra Hamacher, M.Sc. for their assistance in data entry as well as Prof Dr Martin Hermann (†), Prof Dr Thomas Quellmann, Dr Christiane Dunker-Schmidt (†) and Gabriele Fobbe for supporting this survey. In addition, we extend our thanks to the participating students as well as to the academic teachers responsible for the clerkships and organisation of the evaluation.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors mentioned contributed to the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. AH reviewed the literature, analysed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. AV analysed and interpreted the data and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. AT reviewed the literature and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. SG designed the questionnaire, designed the study and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. BW conceived and designed the study and drafted the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on the declaration of interests and declare that we have no competing interests. All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Essen, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data from the whole survey are available on request. Please contact the corresponding author:

Prof Dr med Birgitta Weltermann, MPH(USA), Institute for General Medicine, University Hospital Essen, Hufelandstr. 55, 45147 Essen / Germany, Tel: +49-201-877-8690, Fax: +49-201-877-869-20, birgitta.weltermann@uk-essen.de.

References

- 1.Song Z, Chopra V, Mcmahon LF. Addressing the primary care workforce crisis. Am J Manag Care 2015;21:e452–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK) [German medical association]. Ärztestatistik 2014: Etwas mehr und doch zu wenig[Statistical data on physicians 2014].

- 3.Simoens S. HJ. The supply of physician services in oecd countries: oecd health working papers 2006. // http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/35987490.pdf (accessed 24 Aug 2016).

- 4.World health organisation. Working together for health. Geneva: World health organisation, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brekke M, Carelli F, Zarbailov N et al. Undergraduate medical education in general practice/family medicine throughout Europe – a descriptive study. BMC Med Educ 2013;13:157 10.1186/1472-6920-13-157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willoughby KA, Rodríguez C, Boillat M et al. Assessing students’ perceptions of the effects of a new Canadian longitudinal pre-clerkship family medicine experience. Educ Prim Care 2016;27:180–7. 10.1080/14739879.2016.1172033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turkeshi E, Michels NR, Hendrickx K et al. Impact of family medicine clerkships in undergraduate medical education: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008265 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lloyd MH, Rosenthal JJ. The contribution of general practice to medical education: expectations and fulfilment. MED Educ 1992;26:488–96. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1992.tb00211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison JM, Murray TS. Career preferences of medical students: influence of a new four-week attachment in general practice. BR J Gen Pract 1996;46:721–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maiorova T, Stevens F, Scherpbier A et al. The impact of clerkships on students’ specialty preferences: what do undergraduates learn for their profession? Med Educ 2008;42:554–62. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruschinski C, Wiese B, Eberhard J et al. Attitudes of medical students towards general practice: effects of gender, a general practice clerkship and a modern curriculum. GMS Z Med Ausbild 2011;28:Doc16 10.3205/zma000728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mol SSL, Peelen JH, Kuyvenhoven MM. Patients’ views on student participation in general practice consultations: a comprehensive review. Med Teach 2011;33:e397–400. 10.3109/0142159X.2011.581712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gündling P. Lernziele im Blockpraktikum Allgemeinmedizin—Vergleich der Präferenzen von Studierenden und Lehrärzten. Z Allg Med 2008;84:218–22. 10.1055/s-2008-1073148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chenot JF, Kochen MM, Himmel W. Student evaluation of a primary care clerkship: quality assurance and identification of potential for improvement. BMC Med Educ 2009;9:17 10.1186/1472-6920-9-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy BT, Hartz A, Merchant ML et al. Quality of a family medicine preceptorship is significantly associated with matching into family practice. Fam Med 2001;33:683–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krause U, Stark R. Vorwissen aktivieren. In: Mandl H, Friedrich HF, eds. Handbuch Lernstrategien. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2006:38–49. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012794supp.pdf (4.2MB, pdf)