Abstract

Introduction

For over a decade, enquiries into adverse perinatal outcomes have led to reports that poor collaboration has been detrimental to the safety and experience of maternity care. Despite efforts to improve collaboration, investigations into maternity care at Morecambe Bay (UK) and Djerriwarrh Health Services (Australia) have revealed that poor collaboration and decision-making remain a threat to perinatal safety. The Labouring Together study will investigate how elements hypothesised to influence the effectiveness of collaboration are reflected in perceptions and experiences of clinicians and childbearing women in Victoria, Australia. The study will explore conditions that assist clinicians and women to work collaboratively to support positive maternity outcomes. Results of the study will provide a platform for consumers, clinician groups, organisations and policymakers to work together to improve the quality, safety and experience of maternity care.

Methods and analysis

4 case study sites have been selected to represent a range of models of maternity care in metropolitan and regional Victoria, Australia. A mixed-methods approach including cross-sectional surveys and interviews will be used in each case study site, involving both clinicians and consumers. Quantitative data analysis will include descriptive statistics, 2-way multivariate analysis of variance for the dependent and independent variables, and χ2 analysis to identify the degree of congruence between consumer preferences and experiences. Interview data will be analysed for emerging themes and concepts. Data will then be analysed for convergent lines of enquiry supported by triangulation of data to draw conclusions.

Ethics and dissemination

Organisational ethics approval has been received from the case study sites and Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (2014–238). Dissemination of the results of the Labouring Together study will be via peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations, and in written reports for each case study site to support organisational change.

Keywords: OBSTETRICS

Strengths and limitations of the study.

The strength of the Labouring Together study is the robust mixed-methods multiple case study design, which will objectively measure the essential elements of collaboration and shared decision-making in the current maternity care context.

The Labouring Together study is innovative as it will provide linkage between interprofessional collaboration and shared decision-making with women in maternity care.

The Labouring Together study will be conducted in four different hospital settings, representing a wide range of regional and metropolitan models of public and private maternity care, with a diverse population of childbearing women.

A limitation to the Labouring Together study is that midwives in private practice are not specifically included because few Victorian hospitals have collaborative agreements with midwives in private practice at the present time.

A potential limitation to the Labouring Together study is the passive recruitment strategy for childbearing women to avoid potential distress to women who may have experienced an adverse perinatal outcome.

Introduction

Maternity care provision in Australia has experienced significant changes over the past 20 years, and it continues to evolve. Health policy reforms in Australia have been particularly directed towards offering more access and choice of models of maternity care to childbearing women,1 2 and for increased support for midwifery care in childbirth.1–3 An international resurgence of midwifery over recent decades has involved the profession seeking to gain greater independence from medical dominance.3 Midwives are recognised as able to provide care for childbearing women and support birth, both within their own professional responsibility and accountability, and in collaboration with other healthcare professionals.3 4 Despite the political impetus for reform, barriers have been identified that continue to hinder successful collaborative practice1 5–15 and partnership with consumers16 for maternity care provision in Australia.

In 2005, a review of maternity care in Queensland, Australia found that many maternity care environments had two cultures of care that were perceived to be in opposition, with differing philosophies, values and ethics around the perception of risk in childbirth.1 One culture of care viewed pregnancy and birth as a low-risk life event, with medical care and intervention to be provided only as needed; whereas the other culture of care viewed pregnancy and birth as a potentially high-risk situation, requiring access to technology, intervention and dedicated medical care.1 The report concluded that both cultures of care were needed in order for maternity care to be effective and were crucial to the future of maternity care, but noted that in many care environments the two cultures were unable to reconcile their differences, and was a major obstacle to change.1

In 2009, a review of maternity services in Australia recommended further reform and expansion of the choice and range of models of maternity care available to women.2 These reforms include that maternity care professionals provide care in ‘collaborative partnerships’, requiring midwives, obstetricians, general practitioners and rural doctors to work as professional equals with different but complementary skills and knowledge. Changes to Commonwealth funding arrangements have included expansion of the role of midwives by initiating changes to and support for professional indemnity insurance for midwives working in collaborative team-based models.2 Studies have shown that despite the recommendations of the reviews, development of a common ground between clinician groups for maternity care provision has proved challenging.6 7 10 11 17 18

Recognition of midwives as equal stakeholders2 for the provision of maternity care has been a significant change in the culture of Australian maternity care. Compared with other models of maternity care, continuity of midwifery care has been evaluated as more cost-effective,19 20 has equal or better outcomes for perinatal morbidity or mortality,21–23 has reduced levels of intervention,20 22 24–28 and has increased maternal satisfaction.3 22 29–32 Despite the growing body of evidence in relation to midwifery care, midwives continue to call for midwifery work to be recognised and valued,33 as they report constraints to working to their full scope of midwifery practice,12 33 and have experienced a lack of respect for their professional accountability.18 33 Debates over contested scope of practice, professional role boundaries and philosophical differences continue to hinder the success of collaborative alliances in maternity care.6 10 12 13 17 34 35

Researchers report a gap in knowledge regarding the true meaning and practice of collaboration in maternity care.5 6 12 17 34 36 For example, studies show the term ‘collaboration’ is used synonymously with different but related terms such as cooperation and teamwork,34 37 to describe processes of information sharing,38 or to assume superordinate authority and veto-power over decision-making of midwives or women alike.6 11 12 39 40 Lack of a common understanding of the term ‘collaboration’ at all levels of healthcare exists, with confounding factors identified from the clinician (individual) level, clinician group (micro) level, organisational (meso) level and healthcare policy (macro) level.8 9 34 41 42

Social theorists recognise the development of a collaborative alliance as a strategy for organisations or groups of individual stakeholders can adopt to promote coordination and cooperation, particularly when there are limitations associated with the traditional adversarial methods of resolving conflicts.43–46 A collaborative alliance can be described as an interorganisational effort to address problems too complex and too protracted to be resolved by unilateral organisational action; collaboration is the process—collaborative alliances are the forms.45 46 Wood and Gray45 46 suggest that collaborative alliances are justified when there are complex issues that one stakeholder alone cannot solve, or to cope with the complexity of the environments.

Essential elements of an effective collaborative alliance are proposed to include individual autonomy and independent decision-making power of all stakeholders in the collaborative alliance; shared rules, norms and structures; an interactive process; a domain orientation; and an action or a decision.46 If autonomy and independent decision-making power is relinquished by an individual stakeholder in the collaborative alliance, a merger is formed, not effective collaboration.46 Stakeholders in the collaborative alliance must have a change-orientated relationship, using an interactive process encapsulating reflection on process and the collective ownership of goals.45–47 The interactive process must be governed by agreed shared norms, rules and structures, with the intention to act or decide on objectives or issues related to the problem domain that brought them together.45 46

Characteristics necessary for effective collaboration between maternity care clinicians have been proposed. These include understanding practice boundaries and shared responsibilities; having strategies for open communication and conflict resolution; and the development of mutual trust between clinicians.34 Current definitions of collaboration in maternity care do not clarify the role of the childbearing woman in the collaborative alliance.34 48 In Australia, guidance on national collaborative maternity care and Victorian maternity capability propose that the woman should be an active participant in her care.2 49 This infers that childbearing women should be considered as active stakeholders in the collaborative alliance for collaborative or ‘shared’50–52 decision-making, rather than as a passive recipient of the actions or decisions of the collaborative alliance. Debate continues on how best to incorporate shared decision-making with women as the consumers of healthcare into the interprofessional collaborative decision-making alliance.50 53–63

In maternity care, clinicians' lack of understanding of women's autonomy with decision-making and the law has been identified as a particular barrier to shared decision-making.64 Women, as the consumers of maternity care, may also experience barriers that affect their engagement with decision-making as part of the collaborative alliance.60 65 Challenging a woman's ability to engage in the collaborative alliance are lack of time,60 lack of familiarity with or access to the healthcare system or preferred model of maternity care,49 66 health policy and/or health funding models,60 67 cultural or language barriers, and/or limited health literacy,60 66 and poverty.67 Women also fear that they may be perceived as a ‘difficult patient’, which may in turn impact on the quality of care they receive.68 Women regularly report experiencing conflicting advice from clinicians, and at times evaluate the experience of maternity care as being fragmented, disjointed and disempowering.69–72

Studies suggest that while collaboration in maternity care is important for all women, it is particularly important for women with complex pregnancies or those who develop complications in childbearing and move from low-risk to high-risk maternity care,34 73 or for women who move geographical location or hospital site.34 73–75 In the state of Victoria, Australia, studies have highlighted the depth of polarised perceptions of stakeholders on the contested boundaries of normal to complicated pregnancy, and the power relationships between them.3 6 10–12 17

Outcomes of poor interprofessional collaboration between maternity care clinicians may include tension, poor communication, territorial, adversarial or subversive behaviour, poor teamwork, and delayed escalation of care.34 39 For childbearing women, the reported outcomes of ineffective interprofessional collaboration are serious, and are known to have had a negative impact on perinatal morbidity and mortality,39 74–77 and to have exposed women and babies to a greater risk of adverse outcomes.2 34 78 As such, poor collaboration is recognised as detrimental to the quality, safety and experience of maternity care.2 75–79

Cultural and organisational characteristics that may influence the effectiveness of collaboration are diverse, and may include the decision-making ability and autonomy of individuals,45 46 leadership,80 communication and informatics, negotiation, professional role,5 9 17 organisational structure, gender inequality,45 81 82 hierarchy and power.38 40 45–48 53 80 83 84 To date, few studies have assessed the association between collaboration and the individual-level, microlevel, mesolevel and macrolevel organisational factors that may influence the effectiveness of the collaborative alliance.42 Studies have also not measured the essential elements of collaboration in maternity practice from the perspectives of either clinicians or women, and the possible influences of organisational culture and context on effective collaboration and decision-making.34 42

The Labouring Together study aims to address the knowledge gaps of collaboration by measuring the essential elements of collaboration and exploring the perspectives of individual stakeholders in the collaborative alliance, underpinned by the comprehensive theory of collaboration developed by Wood and Gray.45 46 The Labouring Together study will investigate and measure key elements essential to collaboration and shared decision-making in maternity care from the viewpoints of clinicians and consumers in a range of models of maternity care in regional and metropolitan Victoria, Australia. The proposed research seeks to identify barriers to and promote enablers of effective collaboration for consumers, for individual clinicians, for organisations and for policymakers, to improve the quality, safety and experience of maternity care.

Methods and analysis

Aims

The aims of the Labouring Together study are to: (1) investigate perceptions of ‘collaborative maternity care’ held by maternity care professionals working in the variety of maternity care models available in Victoria, Australia; (2) investigate how the essential elements hypothesised to influence the effectiveness of collaborative alliances are reflected in perceptions of collaboration in maternity care in Victoria; and (3) investigate the preference for and experience of shared decision-making with the childbearing woman as a member of the collaborative alliance.

The research questions that will be answered by the Labouring Together study are:

Who are the stakeholders in the collaborative alliance in maternity care in Victoria?

What perceptions do the stakeholders have of the meaning of collaboration in maternity care?

What are the interests of the stakeholders who participate in the collaborative alliance and to what extent are the interests shared, differing or opposing?

If the stakeholders perceive the collaborative alliance to increase complexity for their own interests, what does the collaborative alliance offer in exchange for this undesired effect?

What are the stakeholders' perceptions of autonomy, and what level of autonomy do the stakeholders hold in the collaborative alliance?

To what extent do childbearing women want to be active participants in decision-making as part of the collaborative alliance, rather than a passive recipient of care?

To what extent do women experience a collaborative approach to care?

Design

The Labouring Together study will use a sequential, mixed-method, multisite case study approach; the multiple sources of evidence offered by this approach will encourage convergent lines of enquiry and triangulation of data.85 This approach will add to the construct validity and reliability of the Labouring Together study, will enhance the generalisability of the results,85 and will enable in-depth exploration of collaboration, within a real-life context.86

The sequential strategy will allow elaboration and expansion of findings from each phase of the Labouring Together study using literal and theoretical replication logic. Replication logic is used in multisite case study research to enhance reliability and external validity by repeating the same case study in multiple case study sites in order to predict similar results in each case study site (literal replication); or to predict or contrasting results for anticipatable reasons (theoretical replication).85 87 Literal replication of similar results across the case study sites will provide compelling support for the Labouring Together study findings. Theoretical replication using the theory of collaboration proposed by Wood and Gray45 46 may predict or anticipate contrasting results between the case study sites, and enable rigour for analysis of the Labouring Together study findings; whereas contradictory results may provide direction for future research.85 The Wood and Gray46 theory of collaboration will also be used for exploration, description and explanation of the collaborative alliances in the clinical contexts,85 and to facilitate analytical generalisation to enhance external validity.

Setting

Four hospitals providing maternity services in Victoria, Australia have been purposively selected to represent the range of models of low-risk and high-risk maternity care in metropolitan and regional Victorian hospitals. Models of care represented in the Labouring Together study are presented in table 1, and are described in table 2.

Table 1.

Case study sites and models of maternity care included in the Labouring Together study

| Case study site | Models of maternity care offered | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Midwifery group practice | Metropolitan Melbourne |

| Midwifery shared care | ||

| GP shared care | ||

| Obstetric high-risk pregnancy care | ||

| Specialist maternity services | ||

| Private obstetric care | ||

| 2 | Midwifery group practice | Outer Metropolitan Melbourne |

| Midwifery shared care | ||

| GP shared care | ||

| Obstetric high-risk pregnancy care | ||

| Specialist maternity services | ||

| Private obstetric care | ||

| 3 | Midwifery shared care | Regional Victoria |

| GP shared care | ||

| Obstetric high-risk pregnancy care | ||

| Specialist maternity services | ||

| 4 | Private obstetric care | Regional Victoria |

GP, general practitioner.

Table 2.

Description of the models of maternity care included in the Labouring Together study

| Model of maternity care | Description |

|---|---|

| Midwifery group practice | Publically funded continuity of low-risk maternity care is primarily provided by a named midwife or small team of midwives throughout pregnancy, birth and in the early weeks of caring for the new baby. |

| Midwifery shared care | Publically funded low-risk maternity care is primarily provided by midwives, shared with obstetric doctors via the maternity hospital throughout pregnancy, birth and in the early weeks of caring for the new baby. |

| GP shared care | Publically or privately funded low-risk to moderate-risk antenatal care is primarily provided by a GP, shared with an obstetrician and/or midwives via the maternity hospital throughout pregnancy and birth and in the early weeks of caring for the new baby. |

| Obstetric high-risk pregnancy care | Publically funded maternity care is provided to women with medically complex pregnancies by a team of obstetricians, physicians, midwives and other healthcare providers throughout pregnancy and birth and in the early weeks of caring for the new baby. |

| Specialist maternity services | Publically funded low-risk to high-risk maternity care is provided to vulnerable women and/or babies by a team of midwives, obstetricians and other healthcare providers throughout pregnancy and birth and in the early weeks of caring for the new baby. |

| Private obstetric care | Privately funded low-risk to high-risk maternity care is provided by a named obstetrician during pregnancy and birth |

GP, general practitioner.

Sample

Within each of the four case study sites, a convenience sample of maternity clinicians and consumers will be recruited; representatives from all groups providing and accessing maternity care will be recruited until saturation of qualitative data has been reached. All eligible clinicians and consumers will be invited to participate in the survey and interviews. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for clinicians and consumers are provided in tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 3.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria (clinicians)

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

Maternity clinicians, currently providing maternity care for one of the case study sites of the Labouring Together study who:

|

Maternity clinicians, not currently providing maternity care for one of the case study sites included in the Labouring Together study Maternity clinicians who are unregistered with the AHPRA, or who have not completed professional qualification status (eg, medical or midwifery students or support workers) Fellows of the RACGP who do not have organisational accreditation to provide maternity care with one of the case study sites included in the Labouring Together study Registered nurses working in maternity services who are not also registered midwives |

AHPRA, Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency; RACGP, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; RANZCOG, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

Table 4.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria (consumers)

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Postnatal women over the age of 18 years | Childbearing women who have experienced a traumatic event or adverse outcome such as a stillbirth (at the discretion of the midwife in charge of the ward, to minimise distress to the woman) Women who cannot read English and who have no access to interpreter services |

Maternity clinicians will be informed of the Labouring Together study by means of posters displayed in the workplace and by presentations to staff at meetings at intervals throughout the duration of the data collection period. This is to ensure that a representative sample of clinicians is achieved to minimise selection bias, as a recent study has suggested that the mean number of contact attempts before completion of a survey per participant in healthcare research is 5.7 times.88 Cross-sectional surveys will be administered to eligible clinicians in paper-based format and electronically, to maximise the response rate and to minimise response bias.88–90 Studies suggest a benchmark of 35–45% for response rates in organisational research,89 91 and as such, a minimum response rate within these parameters will be deemed acceptable by the Labouring Together study.

Consumers of maternity care will be informed of the Labouring Together study by means of posters displayed in the patient areas of the postnatal ward. Paper surveys will be offered to eligible childbearing women at the discretion of the midwife in charge of the postnatal ward, to minimise distress to women who have experienced a traumatic event or adverse outcome such as a stillbirth. To ensure that childbearing woman who wish to participate in the study are offered an opportunity to opt-in to the study, posters advertising the Labouring Together study will include the contact details of the researchers. This approach will be adopted to mitigate the limitations associated with the passive approach to recruitment recommended by the research ethics committee. Women under the age of 18 years or non-English speaking without access to interpreter services will be excluded from the Labouring Together study. Field et al90 reported that response rates between 13% and 39% are common in healthcare research, and as such, a minimum response rate within these parameters will be deemed acceptable by the Labouring Together study.

Data sources

Descriptive data

To provide a comprehensive description of the context of care for each case study site, descriptive data regarding the model of care, demographic characteristics of the consumers and consumer outcomes will be collected. These data will determine the nature, context and services provided at each case study site, and identify what is common and what is unique to each case study site. A predesigned proforma will be used to ensure consistent and objective reporting across all case study sites. Maternity managers at each case study site will be asked to review the data to ensure an authentic representation of each site is captured.

Selected clinical outcome data will also be collected, including the rates of induction of labour, caesarean section rates and use of epidural for ‘standard primiparae’.92 Standard primiparae are defined as women between 20 and 34 years of age who gave birth for the first time, free of obstetric and specific medical complications, with a singleton pregnancy at term gestation (371–406 weeks), not small for gestational age (≥10th centile) newborn, with cephalic presentation. Standard primiparae are by definition at low risk of complications and so intervention rates should be low and outcomes consistent across all hospitals.92

These data are important because they provide indicators of practice, quality and workload and also give an indication about the demographic characteristics of the population each site serves which are key elements of the context of care and practice. The clinical outcome data are routinely reported on for maternity services in the state of Victoria as part of the Victorian perinatal services performance indicators, and are published in the public domain to allow consumers to make informed decisions about their own care and care of their baby.92

Instruments

Context Assessment Index

Clinician perceptions of organisational factors that may influence their ability to integrate childbearing women as stakeholders of the collaborative alliance will be explored by the Context Assessment Index (CAI).93 The CAI examines organisational context by reviewing perceptions of clinicians on the receptiveness of the organisation to change and to develop work practices that are ‘person centred’.93 The theoretical framework underpinning development of the CAI is the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS).94 According to the PARiHS framework, successful implementation of evidence in practice is dependent on the inter-relationship between the nature of the evidence, the quality of the context and expert facilitation. As such, a comprehensive method of assessing context is required.93 The measures of homogeneity were calculated to measure internal reliability.

Validation of the CAI included principal components analysis, exploratory factor analysis, and expert panel feedback, testing for psychometric properties of internal consistency and test–retest scores, and telephone interviews to gauge the usability of the instrument.93 The measures of homogeneity were calculated to measure internal reliability. The Cronbach's α score for the complete questionnaire was estimated at 0.93. Test–retest scores indicated reliability of the findings, and feedback from focus group participants suggested that the instrument had practical utility.93

These stages of development and testing resulted in a final 37-item test,93 measuring three contextual elements: culture (collaborative practice), leadership (respect for persons) and evaluation (evidence informed practice).93 For the purpose of the CAI, the characteristics of each element will be assessed on a continuum from ‘weak’ to ‘strong’. For an effective culture that is receptive to change and has ‘person centred’ ways of working, all three elements need to be ‘strong’.93

The measures of homogeneity were calculated to measure internal reliability. The Cronbach's α score for the complete questionnaire was estimated at 0.93. All five factors achieved a satisfactory estimated level of internal consistency in scoring, ranging from 0.78 to 0.91. Test–retest scores indicated reliability of the findings, and feedback from focus group participants suggested that the instrument had practical utility.93 Permission to use the CAI has been obtained from the authors (personal communication, 16 July 2012).

Jefferson Scale of Attitudes Toward Physician–Nurse Collaboration Instrument (Jefferson Scale)

Clinician stakeholder attitudes towards collaboration and particularly their perception of clinician autonomy within the multiprofessional team will be measured using the Jefferson Scale of Attitudes Toward Physician–Nurse Collaboration Instrument.95 The Jefferson Scale of Attitudes Toward Physician Nurse–Collaboration Instrument has been widely used across a variety of disciplines and international healthcare settings, including undergraduate education,96–98 nurse practitioners,99 advanced practice nurses,100 acute hospital care,101–104 primary care,105 general practice, anaesthesia,106 107 in Italy,103 Israel,103 Mexico,103 Sweden,98 105 USA,99 103 104 107 Turkey96 and Japan.101 Permission has been obtained from the author to use the scale, and to alter the wording within the instrument of ‘nurse’ to ‘midwife’, and ‘physician’ to ‘obstetrician’ (personal communication, 15 May 2012).

Validation of the instrument included factor analysis indicating the survey measured four underlying constructs: shared education and collaborative relationships, caring as opposed to curing, autonomy, and authority. A scale was developed in which 15 items of the survey with large factor loadings were included. The α reliability estimates of the scale were 0.84 and 0.85, respectively.95 Items in the instrument are directly calculated based on their Likert scores (strongly agree=4, strongly disagree=1), with two statements reverse scored. The total score is the sum of all item scores. The higher the score, the more positive attitudes are towards physician–nurse collaboration.103

As recommended by Hojat et al,103 the scores for the four factors will be transformed to a standard distribution with a mean of 100 and an SD of 10 for easier and more meaningful comparisons. Two-way multivariate analysis of variance will be used to simultaneously compare the scores on the dependent variables (the four factors of collaboration) by the independent variables (case study site and professional group),103 using the IBM SPSS Statistics V.22.0 analytical software (IBM. SPSS Statistics for windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, Released 2013).

Control Preferences Scale

The extent to which women want to be active participants in decision-making, followed by their actual experience of decision-making in their maternity care will be measured by using the Control Preferences Scale (CPS).108 The CPS uses statements and cartoons to assess consumer preferences for control in decision-making in healthcare. The CPS is a five-point scale representing the degree of treatment control patients wish to relinquish (ie, passive), retain (ie, active) or share (ie, collaborative) over treatment decision-making. Each role is described by a statement and a cartoon, for example: (A) I prefer to make the decision about which treatment I will receive. (D) I prefer that my doctor makes the final decision about which treatment will be used, but seriously considers my opinion.108

Women will be asked to view the five statements and cartoons to rate their preferences for decisional control during their maternity care. The women will then be asked to view the five statements and cartoons again to rate their actual experiences of decision control during their maternity care. This method will provide an index of how childbearing women believe their maternity care models are accommodating their preference for decisional control. The χ2 analysis will give an indication of the degree of congruence, and whether there is significant congruence between the preferred role and the actual role for consumer decision-making in maternity care.108 To minimise intrusion on participants, the CPS will be presented in the fixed-scale format of incorporating in the one survey the statement and cartoons to illustrate each option for preferences and experiences. The survey will be administered in a paper-based format to women on the postnatal ward.

A meta-analysis of six studies using the CPS to rate both preference and experience of decisional control in cancer care reported 61% concordance (ie, patients' preferred and actual roles were the same). Only 6% of patients experienced extreme discordance between their preferred and actual roles (ie, wanting an active role and experiencing a passive role, or vice versa).109 The CPS has not yet been used in the maternity care context, and understanding of the level of concordance (or discordance) with decisional control and experience of childbearing women is essential for the Labouring Together study to explore extent that childbearing women want to be active participants in decision-making as part of the collaborative alliance, rather than a passive recipient of care.

Semistructured interviews

Clinician interviews

Clinicians will be interviewed, either face-to-face or over the telephone, to explore their perceptions of collaboration and decision-making in maternity care. An interview guide will be used (refer to box 1), which is underpinned by Wood and Gray's45 46 theory of collaboration providing opportunity to explore perceptions and experiences of collaboration, stakeholder interests for participation in the collaborative alliance, and the decision-making role and autonomy of individual stakeholders in the collaborative alliance. To ensure views of all groups of maternity care professionals are represented, all registered clinicians participating in maternity care in each case study site will be invited to participate. Data collection will continue until clinicians from all models of care have been sampled and data saturation has been reached.

Box 1. Semistructured clinician interview guide.

Question 1: In the course of a typical day, with which groups of clinicians or women do you interact in the provision of maternity care?

Question 2: What do you understand by the term ‘collaboration’ in maternity care?

Question 3: How do you participate in collaboration in maternity care in your current practice?

Question 4: What conditions do you consider helpful for successful collaborative maternity practice?

Question 5: What conditions do you consider are barriers to collaborative maternity practice?

Question 6: What advantages are there for you (as an individual) to participate in collaborative maternity practice?

Question 7: What disadvantages are there for you to participate in collaborative maternity practice?

If disadvantages identified: In light of these disadvantages, what motivates you to continue to participate in the collaborative maternity team?

Question 8: What are advantages or disadvantages of collaborative maternity practice overall?

Consumer interviews

Postnatal women will be interviewed over the telephone to explore their perceptions and experiences of collaboration and decision-making in the course of their maternity care. An interview guide (refer to box 2), underpinned by the Wood and Gray45 46 theory of collaboration, and the SURE test (Sure of myself; Understand information; Risk-benefit ratio; Encouragement) to assess consumer satisfaction with decision-making and decisional conflict.60 68 The SURE test is a four-item screening test for decisional conflict in patients, validated with pregnant women considering prenatal screening for Down syndrome. The four-item SURE screening test was developed to help health professionals identify patients with clinically significant decisional conflict.68

Box 2. Semistructured consumer interview template.

Question 1: Which type of maternity care did you choose?

Question 2: Did you get to know/build up a relationship with the midwives/doctors during your antenatal care?

Did you feel able to talk about things that were worrying you?

Were you able to ask questions?

Question 3: What was your experience of decision-making during your pregnancy care?

Were you aware when decisions about your pregnancy care needed to be made?

Did you feel that you had enough information to make an informed decision?

Question 4: Think about one aspect of your pregnancy, labour or postnatal care where you had to make a decision. When you were making your decision:

Did you feel sure about the best choice for you or your baby? Yes or no, please explain.

Did you know the benefits or risks of all options? Yes or no, please explain.

Were you clear about which risks or benefits mattered most to you? Yes or no, please explain.

Do you think that you had enough support and advice to make the choice? Yes or no, please explain.

Question 5: Have you got any other thoughts or suggestions to improve the way decisions are made in maternity care in the future?

Data collection will continue until childbearing women who have accessed maternity care from the range of maternity models identified in the study have been sampled and data saturation has been reached. Interviews will be audio-recorded and transcribed. Data will be coded and analysed for emerging themes and concepts throughout the data collection process, using an inductive approach to condense the raw data into summary format to allow linkage between the data and the aims of the Labouring Together study.110 This method will allow the interplay between the collection of data and reflection on data through both content and thematic analysis,111 and enable the researcher to establish when saturation of data has been reached.

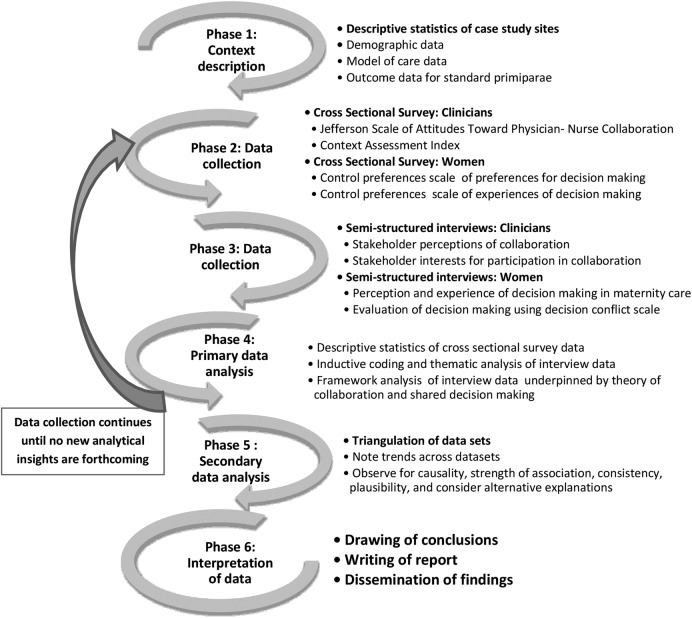

Procedure

The procedure for each case study site will include consultation and engagement with each clinician group to optimise recruitment to the study. Data collection began in August 2015 and will continue until December 2017. A diagram illustrating the phases of the Labouring Together study can be found in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Phases of the Labouring Together study.

Synthesis of data

The multiple sources of evidence generated by the mixed-methods multiple site case study design will ensure construct validity and reliability of the Labouring Together study. Cross-case synthesis and pattern matching from all four case study sites will be used to search for inference of analytical generalisation,85 using Wood and Gray's45 46 theory of collaboration to compare the empirical results of each case study. Internal validity of the case study findings will be ensured by the questioning of inferences and testing of rival explanations; evidence will be reviewed for convergence. Replication logic will enhance the external validity and generalisability of the Labouring Together study across the four case study sites.85

Discussion

National guidance on collaborative maternity care and changes in the Australian National Healthcare Standards aimed at partnering with consumers have shifted the focus of care from the professional and organisational interests of maternity services to the interests of the woman and her family. Inclusion of women as members of the collaborative alliance has the potential to transcend established barriers to collaboration between maternity care professionals; however, studies to date have not investigated how this may be achieved.

Behavioural science theorists suggest that successful collaboration can be achieved by exploring the following domains: why the collaboration was convened and what is it aiming to achieve; the implications of collaboration for either control or mitigation of complexity and risk; the identification of stakeholders in the proposed alliance; and the relationship between self-interests and the collective interests of the stakeholders.

Using the comprehensive theoretical framework of collaboration proposed by Wood and Gray,45 46 the Labouring Together study will enable all stakeholders, including childbearing women, to reflect on collaboration in the current Victorian maternity care context. Enablers of effective collaboration will be identified, and barriers to collaboration will be explored in more depth to seek opportunities for resolution and enable innovation to transcend the impasse.

Ethics and dissemination

Confidentiality and anonymity of the data will be strictly maintained. Audio-recording of the interviews will only take place after informed consent is obtained from participants. Participants will not be identifiable in any transcripts, or in any publications. It will be made clear to all participants that they have the right to withdraw from the research at any time.

The research seeks to identify enablers of effective collaboration for individual clinician groups, for organisations and for consumers. Results of the Labouring Together study will provide a platform for consumers, individual clinician groups, organisations, Government agencies and policymakers to work together to improve the quality, safety and experience of maternity care.

Dissemination of the results of the Labouring Together study will be via peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations. Key findings of the Labouring Together study will be also be presented in workshops and seminars, and written by reports for each case study site to support organisational change.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Vanessa Watkins @VanessaWatkin20 and Bridie Kent @BridieKent

Contributors: VW conceptualised the project and drafted the manuscript. All authors have been involved in developing the study design and the drafting and revisions of this manuscript. All authors have approved this final version for publication.

Funding: This work was supported by 2015 Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (Victorian Branch) Research Grant, and Deakin University through the academic support for PhD study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Organisational ethics approval has been received from the recruitment sites and Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (2014-238).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The Labouring Together study will generate data pertaining to control preferences and experiences of childbearing women; and attitudes towards midwife-obstetrician collaboration. Data collection is ongoing but may be accessible once PhD thesis is complete.

References

- 1.Hirst C. Re-birthing. Report of the Review of Maternity Services in Queensland. Queensland: Queensland Health, Queensland Government, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryant R. Improving maternity services in Australia: the report of the maternity services review. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiger K. The politics of midwifery in Australia: tensions, debates and opportunities. Ann Rev Health Soc Sci 2000;10:53–64. 10.5172/hesr.2000.10.1.53 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Confederation of Midwives (ICM). ICM International Definition of the Midwife 2011. http://www.internationalmidwives.org/assets/uploads/documents/Definition%20of%20the%20Midwife%20-%202011.pdf (accessed 21 Nov 2016).

- 5.Lane K. The plasticity of professional boundaries: a case study of collaborative care in maternity services. Health Sociol Rev 2006;15:341–52. 10.5172/hesr.2006.15.4.341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiger KM, Lane KL. Working together: collaboration between midwives and doctors in public hospitals. Aust Health Rev 2009;33:315–24. 10.1071/AH090315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmied V, Mills A, Kruske S et al. The nature and impact of collaboration and integrated service delivery for pregnant women, children and families. J Clin Nurs 2010;19:3516–26. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03321.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heatley M, Kruske S. Defining collaboration in Australian maternity care. Women Birth 2011;24:53–7. 10.1016/j.wombi.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hastie C, Fahy K. Inter-professional collaboration in delivery suite: a qualitative study. Women Birth 2011;24:72–9. 10.1016/j.wombi.2010.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lane K. When is collaboration not collaboration? When it's militarized. Women Birth 2012;25:29–38. 10.1016/j.wombi.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane K. Dreaming the impossible dream: ordering risks in Australian maternity care policies. Health Sociol Rev 2012;21:23–35. 10.5172/hesr.2012.21.1.23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McIntyre M, Francis K, Chapman Y. The struggle for contested boundaries in the move to collaborative care teams in Australian maternity care. Midwifery 2012;28:298–305. 10.1016/j.midw.2011.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Psaila K, Schmied V, Fowler C et al. Interprofessional collaboration at transition of care: perspectives of child and family health nurses and midwives. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:160–72. 10.1111/jocn.12635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dietz HP, Exton L. Natural childbirth ideology is endangering women and babies. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2016;56:447–9. 10.1111/ajo.12524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellwood D, Oats J. Response to ‘natural childbirth ideology is endangering women and babies’. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2016;56:557–7. 10.1111/ajo.12566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKinnon LC, Prosser SJ, Miller YD. What women want: qualitative analysis of consumer evaluations of maternity care in Queensland, Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:366 10.1186/s12884-014-0366-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lane KL. Still suffering from the ‘silo effect’: lingering cultural barriers to collaborative care. Can J Midwifery Res Pract 2005;4:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter B. Emotion work and boundary maintenance in hospital-based midwifery. Midwifery 2005;21:253–66. 10.1016/j.midw.2004.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenny C, Devane D, Normand C et al. A cost-comparison of midwife-led compared with consultant-led maternity care in Ireland (the MidU study). Midwifery 2015;31:1032–8. 10.1016/j.midw.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tracy SK, Welsh A, Hall B et al. Caseload midwifery compared to standard or private obstetric care for first time mothers in a public teaching hospital in Australia: a cross sectional study of cost and birth outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:348 10.1186/1471-2393-14-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laws PJ, Xu F, Welsh A et al. Maternal morbidity of women receiving birth center care in New South Wales: a matched-pair analysis using linked health data. Birth 2014;41:268–75. 10.1111/birt.12114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S et al. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(8):CD004667 10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rayment-Jones H, Murrells T, Sandall J. An investigation of the relationship between the caseload model of midwifery for socially disadvantaged women and childbirth outcomes using routine data—a retrospective, observational study. Midwifery 2015;31:409–17. 10.1016/j.midw.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Homer CSE, Davis GK, Brodie PM et al. Collaboration in maternity care: a randomised controlled trial comparing community-based continuity of care with standard hospital care. BJOG 2001;108:16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahlen HG, Tracy SK, Tracy MB et al. Rates of obstetric intervention among low-risk women giving birth in private and public hospitals in NSW: a population-based descriptive study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001723 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tracy SK, Hartz DL, Tracy MB et al. Caseload midwifery care versus standard maternity care for women of any risk: M@NGO, a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;382:1723–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61406-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stapleton SR, Osborne C, Illuzzi J. Outcomes of care in birth centers: demonstration of a durable model. J Midwifery Womens Health 2013;58:3–14. 10.1111/jmwh.12003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong N, Browne J, Ferguson S et al. Getting the first birth right: a retrospective study of outcomes for low-risk primiparous women receiving standard care versus midwifery model of care in the same tertiary hospital. Women Birth 2015;28:279–84. 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waldenstrom U, Brown S, McLachlan H et al. Does team midwife care increase satisfaction with antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care? A randomized controlled trial. Birth 2000;27:156 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00156.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tingstig C, Gottvall K, Grunewald C et al. Satisfaction with a modified form of in-hospital birth center care compared with standard maternity care. Birth 2012;39:106–14. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2012.00533.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coyle KL, Hauck Y, Percival P et al. Normality and collaboration: mothers’ perceptions of birth centre versus hospital care. Midwifery 2001;17:182–93. 10.1054/midw.2001.0256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butler MM, Sheehy L, Kington MM et al. Evaluating midwife-led antenatal care: choice, experience, effectiveness, and preparation for pregnancy. Midwifery 2015;31:418–25. 10.1016/j.midw.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Homer CSE, Passant L, Brodie PM et al. The role of the midwife in Australia: views of women and midwives. Midwifery 2009;25:673–81. 10.1016/j.midw.2007.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Downe S, Finlayson K, Fleming A. Creating a collaborative culture in maternity care. J Midwifery Womens Health 2010;55:250–4. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2010.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sidebotham M, Fenwick J, Rath S et al. Midwives’ perceptions of their role within the context of maternity service reform: an appreciative inquiry. Women Birth 2015;28:112–20. 10.1016/j.wombi.2014.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Essen C, Freshwater D, Cahill J. Towards an understanding of the dynamic sociomaterial embodiment of interprofessional collaboration. Nurs Inq 2015;22:210–20. 10.1111/nin.12093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boon HS, Mior SA, Barnsley J et al. The difference between integration and collaboration in patient care: results from key informant interviews working in multiprofessional healthcare teams. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009;32:715–22. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armitage P. Joint working in primary healthcare. Nurs Times 1983;79:75–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saleem S, McClure EM, Goudar SS et al. A prospective study of maternal, fetal and neonatal deaths in low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ 2014;92:605–12. 10.2471/BLT.13.127464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray-Davis B, Marshall M, Gordon F. Becoming an interprofessional practitioner: factors promoting the application of pre-qualification learning to professional practice in maternity care. J Interprof Care 2014;28:8–14. 10.3109/13561820.2013.820690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lyndon A, Zlatnik MG, Maxfield DG et al. Contributions of clinical disconnections and unresolved conflict to failures in intrapartum safety. JOGNN 2014;43:2–12. 10.1111/1552-6909.12266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mulvale G, Embrett M, Razavi SD. ‘Gearing up’ to improve interprofessional collaboration in primary care: a systematic review and conceptual framework. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:83 10.1186/s12875-016-0492-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aldrich H. Resource dependence and interorganizational relations: local employment service offices and social services sector organizations. Adm Soc 1976;7:419–54. 10.1177/009539977600700402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gray B. Conditions facilitating interorganizational collaboration. Hum Relations 1985;38:911–36. 10.1177/001872678503801001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gray B, Wood D. Collaborative alliances: moving from practice to theory. J Appl Behav Sci 1991;27:3–22. 10.1177/0021886391271001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wood DJ, Gray B. Toward a comprehensive theory of collaboration. J Appl Behav Sci 1991;27:139–62. 10.1177/0021886391272001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bronstein LR. A model for interdisciplinary collaboration. Soc Work 2003;48:297–306. 10.1093/sw/48.3.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith DC. Midwife-physician collaboration: a conceptual framework for interprofessional collaborative practice. J Midwifery Womens Health 2015;60:128–39. 10.1111/jmwh.12204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pearson DDR. The Victorian Auditor-General's Report. Maternity services: capability Melbourne: Victorian Government Printer, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stacey D, Légaré F, Pouliot S et al. Shared decision-making models to inform an interprofessional perspective on decision-making: a theory analysis. Patient Educ Couns 2010;80:164–72. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Légaré F, Stacey D, Pouliot S et al. Interprofessionalism and shared decision-making in primary care: a stepwise approach towards a new model. J Interprof Care 2011;25:18–25, 8p 10.3109/13561820.2010.490502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Légaré F, Politi MC, Drolet R et al. Training health professionals in shared decision-making: an international environmental scan. Patient Educ Couns 2012;88:159–69. 10.1016/j.pec.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.D'Amour D, Ferrada-Videla M, San Martin Rodriguez L et al. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: core concepts and theoretical frameworks. J Interprof Care 2005;19(Suppl 1):116–31. 10.1080/13561820500082529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF. Multiple perspectives on shared decision-making and interprofessional collaboration in mental healthcare. J Interprof Care 2013;27:223–30. 10.3109/13561820.2013.767225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF. Shared decision-making and interprofessional collaboration in mental healthcare: a qualitative study exploring perceptions of barriers and facilitators. J Interprof Care 2013;27:373–9. 10.3109/13561820.2013.785503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gabrielsson S, Looi GME, Zingmark K et al. Knowledge of the patient as decision-making power: staff members’ perceptions of interprofessional collaboration in challenging situations in psychiatric inpatient care. Scand J Caring Sci 2014;28:784–92. 10.1111/scs.12111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ho A, Jameson K, Pavlish C. An exploratory study of interprofessional collaboration in end-of-life decision-making beyond palliative care settings. J Interprof Care 2016;30:795–803. 10.1080/13561820.2016.1203765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oishi A, Murtagh FEM. The challenges of uncertainty and interprofessional collaboration in palliative care for non-cancer patients in the community: a systematic review of views from patients, carers and healthcare professionals. Palliat Med 2014;28:1081–98. 10.1177/0269216314531999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Supper I, Catala O, Lustman M et al. Interprofessional collaboration in primary healthcare: a review of facilitators and barriers perceived by involved actors. J Public Health (Oxf) 2015;37:716–27. 10.1093/pubmed/fdu102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Légaré F, Witteman HO. Shared decision-making: examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:276–84. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision-making. Patient Educ Couns 2014;94:291–309. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stevens G, Thompson R, Watson B et al. Patient decision aids in routine maternity care: benefits, barriers, and new opportunities. Women Birth 2016;29:30–4. 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clark K, Beatty S, Reibel T. Maternity care: a narrative overview of what women expect across their care continuum. Midwifery 2015;31:432–7. 10.1016/j.midw.2014.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kruske S, Young K, Jenkinson B et al. Maternity care providers’ perceptions of women's autonomy and the law. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:84–84. 10.1186/1471-2393-13-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.VandeVusse L. Decision-making in analyses of women's birth stories. Birth 1999;26:43–50. 10.1046/j.1523-536x.1999.00043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Institute of Medicine (IOM). Improving diagnosis in healthcare. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noseworthy DA, Phibbs SR, Benn CA. Towards a relational model of decision-making in midwifery care. Midwifery 2013;29:e42–8. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Légaré F, Kearing S, Clay K et al. Are you SURE?: assessing patient decisional conflict with a 4-item screening test. Can Family Phys 2010;56:e308–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown S, Lumley J. Satisfaction with care in labor and birth: a survey of 790 Australian Women. Birth 1994;21:4–13. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.1994.tb00909.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Janssen BM, Wiegers TA. Strengths and weaknesses of midwifery care from the perspective of women. Evid Based Midwifery 2006;4:53. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Larkin P, Begley CM, Devane D. ‘Not enough people to look after you’: an exploration of women's experiences of childbirth in the Republic of Ireland. Midwifery 2012;28:98–105. 10.1016/j.midw.2010.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nair M, Yoshida S, Lambrechts T et al. Facilitators and barriers to quality of care in maternal, newborn and child health: a global situational analysis through metareview. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004749 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Downe S, Byrom S, Simpson L, eds. Essential midwifery practice: expertise leadership and collaborative working. 1st edn Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; , 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wallace EM.2015. Report into an investigation into perinatal outcomes at Djerriwarrh Health Services. https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/~/media/health/files/collections/research%20and%20reports/e/djerriwarrh%20-%20wallace%20report%20-%20executive%20summary.pdf.

- 75.Duckett S.2016. Targeting zero. Supporting the Victorian hospital system to eliminate avoidable harm and strengthen quality of care. Report of the Review of Hospital Safety and Quality Assurance in Victoria. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/hospitals-and-health-services/quality-safety-service/hospital-safety-and-quality-review.

- 76.Lewis G. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving Mothers’ Lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer- 2003–2005. The Seventh Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom London, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kirkup B. The Report of the Morecambe Bay Investigation. London: The Stationery Office, Mar 2015.

- 78.National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). National guidance on collaborative maternity care. Canberra: NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council), 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Frost P. Patient safety in Victorian public hospitals. Victorian Auditor-General's Office, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith AHK, Dixon AL, Page LA. Healthcare professionals’ views about safety in maternity services: a qualitative study. Midwifery 2009;25:21–31. 10.1016/j.midw.2008.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.MacMillan KM. The challenge of achieving interprofessional collaboration: should we blame Nightingale? J Interprof Care 2012;26:410–15. 10.3109/13561820.2012.699480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hastie C. Midwifery: women, history and politics. Birth Issues 2006;15:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kuziemsky C, Reeves S. The intersection of informatics and interprofessional collaboration. J Interprof Care 2012;26:437–9. 10.3109/13561820.2012.728380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bell AV, Michalec B, Arenson C. The (stalled) progress of interprofessional collaboration: the role of gender. J Interprof Care 2014;28:98–102. 10.3109/13561820.2013.851073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yin RK. Case study research designs and methods. 4th edn Thousand Oaks, California, USA: Sage Publications, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stake RE. The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches . 3rd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Clark M, Rogers M, Foster A et al. A randomized trial of the impact of survey design characteristics on response rates among nursing home providers. Eval Health Prof 2011;34:464–86. 10.1177/0163278710397791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Burke M, Hodgins M. Is ‘dear colleague’ enough? Improving response rates in surveys of healthcare professionals. Nurse Res 2015;23:8–15. 10.7748/nr.23.1.8.e1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Field TS, Cadoret CA, Brown ML et al. Surveying physicians do components of the “total design approach” to optimizing survey response rates apply to physicians? Med Care 2002;40:596–605. 10.1097/00005650-200207000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Baruch Y, Holtom BC. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum Relations 2008;61:1139–60. 10.1177/0018726708094863 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hunt RC. Victorian perinatal services performance indicators 2013–2014. Victoria: Victorian State Government, Department of Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 93.McCormack B, McCarthy G, Wright J et al. Development and testing of the Context Assessment Index (CAI). Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2009;6:27–35. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kitson AL, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G et al. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges. Implement Sci 2008;3:1 10.1186/1748-5908-3-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hojat M, Fields SK, Veloski JJ et al. Psychometric properties of an attitude scale measuring physician-nurse collaboration. Eval Health Prof 1999;22:208–20. 10.1177/01632789922034275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ardahan M, Akçasu B, Engin E. Professional collaboration in students of medicine faculty and school of nursing. Nurse Educ Today 2010;30:350–4. 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ward J, Schaal M, Sullivan J et al. The Jefferson scale of attitudes toward physician-nurse collaboration: a study with undergraduate nursing students. J Interprof Care 2008;22:375–86. 10.1080/13561820802190533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hansson A, Foldevi M, Mattsson B. Medical students’ attitudes toward collaboration between doctors and nurses—a comparison between two Swedish universities. J Interprof Care 2010;24:242–50. 10.3109/13561820903163439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jones ED, Letvak S, McCoy TP. Reliability and validity of the Jefferson scale of attitudes toward physician–nurse collaboration for nurse practitioners. J Nurs Meas 2013;21:463–76. 10.1891/1061-3749.21.3.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zander PA. Attitudes of physicians and advanced practice nurses toward collaborative practice. Barry University School of Nursing, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Onishi M, Komi K, Kanda K. Physicians’ perceptions of physician-nurse collaboration in Japan: effects of collaborative experience. J Interprof Care 2013;27:231–7. 10.3109/13561820.2012.736095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hojat M, Nasca TJ, Cohen MJM et al. Attitudes toward physician-nurse collaboration: a cross-cultural study of male and female physicians and nurses in the United States and Mexico. Nurs Res 2001;50:123–8. 10.1097/00006199-200103000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ et al. Comparisons of American, Israeli, Italian and Mexican physicians and nurses on the total and factor scores of the Jefferson scale of attitudes toward physician-nurse collaborative relationships. Int J Nurs Stud 2003;40:427–35. 10.1016/S0020-7489(02)00108-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.McCaffrey R, Hayes RM, Cassell A et al. The effect of an educational programme on attitudes of nurses and medical residents towards the benefits of positive communication and collaboration. J Adv Nurs 2012;68:293–301. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05736.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hansson A, Arvemo T, Marklund B et al. Working together—primary care doctors’ and nurses’ attitudes to collaboration. Scand J Public Health 2010;38:78–85. 10.1177/1403494809347405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jones TS, Fitzpatrick JJ. CRNA-physician collaboration in anesthesia. AANA J 2009;77:431–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Taylor CL. Attitudes toward physician-nurse collaboration in anesthesia. AANA J 2009;77:343–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The control preferences scale. Can J Nurs Res 1997;29:21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Singh JA, Sloan JA, Atherton PJ et al. Preferred roles in treatment decision-making among patients with cancer: a pooled analysis of studies using the control preferences scale. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:688–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval 2006;27:237–46. 10.1177/1098214005283748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bowling A. Research methods in health. Investigating health and health services. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]