Abstract

The South-East Asia region, with 11 member states, has an estimated 3.5 million people living with HIV (PLHIV). More than 99% of PLHIV live in five countries where HIV prevalence among the population aged 15–49 remains low but is between 2% and 29% among key populations. Since 2010, the region has made progress to combat the epidemic. Mature condom programmes exist in most countries but opioid substitution therapy, and needle and syringe exchange programmes need to be scaled up. HIV testing is recommended nationwide in four countries and is prioritised in high prevalence areas or for key populations in the rest. In 2015, PLHIV aware of their HIV status ranged from 26% to 89%. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is recommended for all PLHIV in Thailand and Maldives while six countries recommend ART at CD4 cell counts <500 cells/mm3. In 2015, 1.4 million (39%) PLHIV were receiving ART compared to 670,000 (20%) in 2010. Coverage of HIV testing and treatment among HIV-positive pregnant women has also improved but remains low in all countries except Thailand, which has eliminated mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis. Between 2010 and 2015, AIDS-related deaths and new HIV infections have shown a declining trend in all the high-burden countries except Indonesia. But the region is far from achieving the 90-90-90 target by 2020 and the end of AIDS by 2030. The future HIV response requires that governments work in close collaboration with communities, address stigma and discrimination, and efficiently invest domestic resources in evidence-based HIV testing and treatment interventions for populations in locations that need them most.

Keywords: HIV prevalence, testing, PMTCT, ART, viral load, key population

Introduction

The HIV/AIDS epidemic still remains a major public health concern in the World Health Organization (WHO) South-East Asia region (the region henceforth). The region, comprising 11 member states, is home to a quarter of the world's population and has the second largest HIV burden after sub-Saharan Africa. Even though HIV prevalence is low at 0.3%, an estimated 3.5 million (3.0 million–4.1 million) people are living with HIV [1]. There were an estimated 180,000 (150,000–210,000) new HIV infections and 130,000 (110,000–150,000) AIDS-related deaths in 2015 [1].

Since 2000, member states in the Region have made significant progress towards Goal 6 of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [2,3]. Prevention and control of HIV has resulted in improved access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and a decline in HIV-related illnesses, deaths and transmission. As the era of MDGs comes to an end and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [4] commence, it is time to assess the Member States’ key achievements in the AIDS response in the last 5 years and identify the gaps and challenges they face. This article describes the current state of the HIV epidemic, the health sector response (inputs, outputs and outcomes along the HIV result chain) and impact of HIV programmes on epidemiological trends for the region and its member states (excluding the Democratic People's Republic of Korea) for the period 2010–2015. Such a review will help guide the HIV response in the near future in order to achieve the end of the AIDS epidemic by 2030 in the region.

Characteristics of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the region

The epidemic is heterogeneous among and within the member states in terms of levels and trends. The number of people living with HIV (PLHIV) has remained more or less stable at 3.5 million (3.0 million–4.1 million) since 2005 and includes 1.3 million (1.1 million–1.5 million) women aged 15 years and above [1]. More than 99% of PLHIV live in five countries: India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nepal and Thailand (Table 1). With 2.1 million (1.7 million–2.6 million) PLHIV, India has the largest number of PLHIV in the region [5]. Five countries (Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Sri Lanka and Timor-Leste) together represent less than 1% of all PLHIV and has been categorised as a low-level epidemic in these countries. Less than 1000 people live with HIV in Bhutan and Timor-Leste (using data from 2014 as 2015 data are unavailable) [6,7]. The Democratic People's Republic of Korea has not reported any case so far.

Table 1.

Epidemiology of the HIV epidemic in the WHO South-East Asia region and 10 member states, 2010–2015

| Country | People living with HIV | AIDS-related deaths | New HIV infections (Total) | New HIV infections in children (0–14) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2010 | 2015 | 2010 | 2015 | 2010 | 2015 | |

| Bangladesh | 9600 | <1000 | <1000 | 1400 | 1100 | <100 | <100 |

| Bhutan | <1000 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| India | 2,100,000 | 120,000 | 68,000 | 100,000 | 86,000 | 15,000 | 10,000 |

| Indonesia | 690,000 | 18,000 | 35,000 | 69,000 | 73,000 | 3000 | 5,000 |

| Maldives | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Myanmar | 220,000 | 16,000 | 9700 | 15,000 | 12,000 | 1800 | <1,000 |

| Nepal | 39,000 | 2600 | 2300 | 2300 | 1300 | <500 | <200 |

| Sri Lanka | 4200 | <100 | <200 | <500 | <1,000 | <100 | <100 |

| Thailand | 440,000 | 19,000 | 14,000 | 12,000 | 6,900 | <500 | <100 |

| Timor-Leste | <1000 | NA | <100 | NA | <100 | NA | NA |

| South-East Asia | 3,500,000 | 170,000 | 130,000 | 200,000 | 180,000 | 23,000 | 16,000 |

HIV prevalence among the adult population aged 15–49, 0.3% in 2015, has remained low and stable across the region [1]. Thailand is the only country with an HIV prevalence of over 1% (Figure 1), which has declined from 1.7% in 2001 to 1.1% in 2015 [5]. The prevalence in India (0.26%), Myanmar (0.8%) and Nepal (0.2%) has remained almost the same during the period 2001–2015 [5,8]; however, it is showing an upward trend in Indonesia (<0.1% in 2001 vs 0.5% in 2015)[5]. There are geographical variations within countries as well, as demonstrated by high prevalence in the southern and northeastern states of India and in Papua and West Papua in Indonesia [8,9].

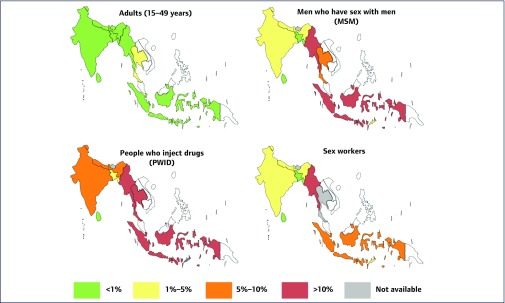

Figure 1.

HIV prevalence among adults (15–49 years) and key populations in 10 member states. Sources: UNAIDS AidsInfo [5], India HIV estimates 2015 [8], and UNAIDS country progress reports for Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal and Timor-Leste [6,7,15,16]. Data are from 2015 except for Timor-Leste (for MSM and sex workers), Bangladesh (for PWID), and Nepal (for sex workers), which are from 2013

The five countries in the region with 99% of the HIV burden are experiencing concentrated epidemics among certain key populations that are at a high risk for acquiring HIV. These include sex workers (SW) and their clients, men who have sex with men (MSM), people who inject drugs (PWID) and transgender individuals. Prevalence rates among PWID were 10% in India, 19% in Thailand, 23% in Myanmar and 29% in Indonesia [5]. They are also high among MSM, ranging from 2.4% in Nepal to 26% in Indonesia [5] (Figure 1).

Health sector responses to HIV

HIV prevention for key populations

Condom programmes have been the cornerstone of HIV prevention in the region. The five countries with a concentrated epidemic have mature condom programmes for key populations and report high condom use among MSM and SWs [5]. Condom use was >80% for MSM in India, Indonesia, Nepal and Thailand, and >90% for SWs in India, Sri Lanka and Thailand (Table 2). However, condom promotion programs for PWID are not getting strong results: India reports the highest rates for the region at 77% [5].

Table 2.

Coverage of key interventions for prevention and treatment of HIV in 10 member states

| Country | Condom use (%) | No. of needles per PWID (2015) | PLHIV aware of their HIV status (2015)(%) | ART coverage (2015)(%) | PLHIV on ART with viral suppression (2015)(%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSM | PWID | Sex workers | All | Pregnant women | All | Children (0–14) | Pregnant women | |||

| Bangladesh | 46 | 35 | 67 | 243 | 36 | NA | 15 | 31 | 14 | 70 |

| Bhutan | NA | 54 | NA | 0 | 40* | NA | 17* | NA | NA | NA |

| India | 84 | 77 | 91 | 259 | 71 | 42 | 43 | NA | 38 | NA |

| Indonesia | 81 | 46 | 68 | 13 | 26 | 25 | 9 | 16 | 9 | NA |

| Maldives | NA | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Myanmar | 77 | 23 | 81 | 223 | NA | NA | 47 | 75 | 77 | 87 |

| Nepal | 86 | 53 | NA | 25 | 57 | 35 | 31 | 58 | 35 | 90 |

| Sri Lanka | 47 | 26 | 93 | 0 | 54 | 24 | 19 | 46 | 24 | NA |

| Thailand | 82 | 47 | 95 | 6 | 89 | 100 | 65 | >95 | >95 | 96 |

| Timor-Leste | 66 | NA | 36 | 0 | NA | 19* | 37* | NA | NA | NA |

Source: UNAIDS AidsInfo [5], UNAIDS Global AIDS Progress Reporting 2014 and 2015 and WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia HIV/AIDS Fact Sheets ( www.searo.who.int/entity/hiv/data/factsheets/en/).

MSM: men who have sex with men; PWID: people who inject drugs; PLHIV: people living with HIV; ART: antiretroviral therapy; NA: not available.

Data for Bhutan and Timor-Leste are from 2014.

Note: Data on condom use are the latest available data 2010–2015.

All but three countries (Bhutan, Sri Lanka and Timor-Leste) have opioid substitution therapy (OST) programmes for PWID [10]. Limited available data show that only 2% of PWID in Bangladesh, 15% in India, 12% in Myanmar and 35% in Indonesia were receiving OST in 2015 [11]. Six countries (Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nepal and Thailand) have needle and syringe exchange programmes for PWID [10] but only India, Bangladesh, and Myanmar have achieved the global standard of over 200 needles distributed per PWID per year in 2015 [5] (Table 2).

In 2015, the WHO issued guidelines that recommend antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) as an additional prevention tool for people at substantial risk of HIV [12]. Thailand is the only country in the region that recommends PrEP for key populations (national treatment guidelines 2014) [13]. Implementation science research of PrEP is ongoing in India and Thailand [14].

HIV testing, care and treatment

HIV testing policies differ across countries. India, Maldives, Myanmar and Thailand recommend HIV testing for all populations nationwide while the others have prioritised testing in high-prevalence areas and/or for high-risk populations. HIV testing services are provided in a variety of facilities such as antenatal (ANC), ART, tuberculosis (TB), sexually transmitted infection and OST clinics [10]. Community-based testing is also provided in some countries to increase accessibility, especially for key populations.

In Thailand, 89% of the estimated number of PLHIV were aware of their HIV status in 2015, this is the only country from the region that is on track to achieve the first of the 90-90-90 targets of 90% of PLHIV diagnosed by 2020 [11] (Table 2). In other countries, the estimated number of PLHIV who have been diagnosed range from 26% in Indonesia to 71% in India (2015) [11]. Fewer PLHIV are aware of their HIV status in countries that prioritise testing geographically or for high-risk populations. Coverage of testing and counselling for key populations also remains low in many countries. The latest available surveillance data show that rates of HIV testing for SWs are highest in India at 91%, followed by Timor-Leste at 66% (2013 data), but stand below 50% in other countries [5]. Testing rates vary from 8% in Sri Lanka to 64% in India for PWID and from 14% in Sri Lanka to 71% in India for MSM [5].

ART eligibility criteria also vary among countries [13]. Of the 10 member states two (Thailand and Maldives) recommend ART irrespective of CD4 cell count for all PLHIV, in line with the recently released 2015 WHO guidelines [12]. Six countries, excluding India and Indonesia, recommend initiation of ART at the 2013 WHO guideline [17] level of CD4 cell count <500 cells/mm3, and irrespective of CD4 counts for PLHIV co-infected with TB or hepatitis B, pregnant women and serodiscordant couples. India and Indonesia recommend treatment at 2010 WHO guideline [18] levels of CD4 cell count <350 cells/mm3 and irrespective of CD4 count for PLHIV co-infected with TB or hepatitis B and pregnant women. Indonesia has also prioritised serodiscordant couples, key populations and PLHIV in high-prevalence areas for ART irrespective of CD4 cell count. Seven countries recommend ART irrespective of CD4 cell count for children below 5 years of age [13]. India recommends ART irrespective of CD4 cell count for children below 2 years of age, while in Sri Lanka and Thailand, ART irrespective of CD4 count is recommended for children aged below 1 year [13]. Since 2010, all countries have updated their treatment guidelines periodically to keep pace with the latest evidence and follow WHO guidelines. As a result, ART scale up has been impressive in the region.

At the end of 2015 more than 1.4 million PLHIV were receiving ART compared to 670,000 in 2010 [1]. ART coverage among the estimated number of PLHIV has nearly doubled from 20% (17–23%) in 2010 to 39% (33–46%) in 2015 [1]. However, the region and its member states have a long way to go in order to achieve the second 90-90-90 [19] target of 81% of estimated PLHIV on ART by 2020. Thailand has the highest coverage of ART at 65% in 2015 (Table 2) compared to 44% in 2010 [5]. India, Myanmar and Nepal have also shown a significant increase in access to ART but only 43%, 47% and 27% of the estimated number of PLHIV were receiving ART, respectively (Table 2). Treatment coverage was extremely low in Indonesia at 9% in 2015 and has improved at a slow pace [5]. ART coverage among children aged 0–14 years show similar trends in the region, from 16% in Indonesia to over 95% in Thailand (Table 2). Limited data are available among key populations. Published studies from India show ART coverage of 16%, 18% and 21–49% among MSM, PWID and SWs, respectively [8,20–23]. Viral load (VL) testing is not widely available except in Thailand. Limited data from four countries show high viral suppression among PLHIV on ART (>85%) in three countries (Myanmar, Nepal and Thailand) compared to 70% in Bangladesh (Table 2).

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT)

Universal access to provider-initiated testing and counselling (PITC) for pregnant women in ANC is recommended in five countries (Bhutan, India, Maldives, Myanmar and Thailand) [10,24]. Of the number of pregnant women who attended an ANC or had a facility-based delivery in the past 12 months, 100% were tested for HIV in Thailand, 85% in Myanmar and 41% in India in 2015 [11]. Five countries (Bangladesh, Indonesia, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Timor-Leste) have prioritised HIV testing in high prevalence areas and the 2015 HIV testing coverage among pregnant women who attended an ANC or had a facility-based delivery varied between 0.1% in Indonesia to 71% in Sri Lanka [11]. Data from 2015 also show that >55% of the estimated HIV-positive pregnant women are unaware of their HIV status in all countries except Thailand, leading to poor outcomes along the PMTCT cascade [11] (Table 2).

Option B+ for pregnant women, wherein all HIV-positive pregnant women are eligible for life-long ART, irrespective of their CD4 cell count, is recommended by all countries. It is either being implemented nationwide (e.g. India and Thailand) or being phased-in, starting with high-prevalence areas (e.g. Bangladesh, Myanmar, Nepal and Timor-Leste) [10]. It is at varying stages of implementation across the region. ART coverage among estimated HIV-positive pregnant women in 2015 was >95% in Thailand (vs 94% in 2010) and 77% in Myanmar (vs 39% in 2010)[5]. PMTCT ART coverage remains low in other countries and has shown some improvement only in Nepal. Indonesia lags far behind, at <10% in 2015 [5].

Thailand leads the region in PMTCT. In June 2016 the country had successfully reduced transmission rates to <2%, becoming the first country in Asia to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis [25].

HIV spending

HIV spending data are available from only six countries in the region. Thailand has the highest among the member states and in 2013 spent US$287 million on their HIV response, up from US$236 million in 2010 (22% increase) [5]. Spending in Myanmar and Indonesia has also increased by 29% (2010–2013) and 26% (2010–2012), respectively, but total HIV spending has decreased in India and Sri Lanka [5].

In Thailand, 89% of the total HIV spending in 2013 was funded from domestic resources [5]. In two countries, Bangladesh and Myanmar, <15% of the HIV response is financed domestically [5]. Indonesia and Sri Lanka are financing 42% and 55% of their HIV response from domestic resources, respectively [5]. Compared to 2010, domestic spending as a proportion of total HIV spending has increased in all countries (Bangladesh, Indonesia, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand), but more domestic funds need to be committed to HIV in most of these countries.

Impact on AIDS-related deaths and new HIV infections

The number of estimated AIDS-related deaths has been declining in the region since peaking at 210,000 in 2005 [1]. There were 130,000 (110,000–150,000) in 2015 compared to 170,000 in 2010 (24% decline) [1]. Of the five high-burden countries, AIDS-related deaths have shown a declining trend in four. During the period 2010–2015, they have decreased by 43% in India, 39% in Myanmar, 12% in Nepal and 26% in Thailand [5]. In Indonesia, they have increased rapidly from 18,000 in 2010 to 35,000 in 2015 [5]. There were <1000 deaths in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Timor-Leste in 2015 [5,7].

Estimated new HIV infections in the region (total and among children aged 0–14) have declined slightly over the period 2010–2015. There were 180,000 (150,000–210,000) new HIV infections in 2015 compared to 200,000 (170,000–230,000) in 2010 (10% decline). There were 16,000 (13,000–19,000) new HIV infections in children in 2015 compared to 23,000 (18,000–26,000) in 2010, a 30% decline [1]. India, Myanmar, Nepal and Thailand have experienced a 14%, 20%, 43% and 43% reduction between 2010 and 2015, respectively[5]. However, there was an increase, including in children, in Indonesia during the same period [5]. There were <1000 new infections in Sri Lanka and Timor-Leste in 2015 [5,7].

Discussion

Since 2010, the WHO South-East Asia region has made progress to combat the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Access to HIV services along the HIV continuum of care has expanded and, overall, the epidemic in the region has stabilised. HIV prevalence in the region and in most of the high-burden countries remains low and constant. New HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths are also showing a declining trend in many countries.

Despite this progress, coverage for prevention, testing and treatment services generally falls substantially short of UNAIDS Fast Track 90-90-90 targets. Less than 65% of PLHIV know their status, only 39% (33–46%) are on ART and VL monitoring is not widely available [1,11]. Access to HIV prevention, testing and treatment for key populations, particularly PWID and MSM, remains insufficient. Other hard-to-reach populations such as prisoners, migrants, children and adolescents are also underserved by the current HIV response. There are wide inter-regional and intra-regional disparities. Therefore a substantial shift in efforts is required to reach the ambitious Fast Track targets for 2020.

In a region largely characterised by concentrated HIV epidemics, it is vital to target the HIV response towards the most affected populations and locations. Countries have prioritised key populations for regular HIV testing and earlier treatment. Community-based organisations and civil society have also spearheaded critical structural changes and HIV prevention programmes, reducing HIV vulnerability of key populations and improving outreach [26–28]. However, these populations still have limited access to HIV-related services and there are difficulties in retaining them in care. There are multiple barriers to a successful HIV response for key populations – stigma and discrimination, lack of knowledge and awareness of positive status, and criminalisation of sex work, homosexuality and drug use [20,29–32]. Stigma reduction as an integral part of HIV prevention programming, community-based and community-led interventions, harm reduction for PWID and legal reforms are urgently needed in the member states. Furthermore, community-based organisations have to be systematically involved in the design, implementation and monitoring of programmes. Strong community–community [33] and government–community partnerships are needed, where governments must play an active role in providing financial and technical support to these organisations.

Expansion of HIV-testing services, especially for key populations, pregnant women, adolescents and HIV-exposed infants, is the key for achieving the fast track goals. Despite the efforts to decentralise testing services and expand community-based testing, coverage remains low. Stigma, discrimination, punitive laws and a lack of awareness remain key barriers to accessing testing [31,34,35]. The rate of institutional deliveries is low; virological testing for infants is not widely available [36] and adolescents do not know where to access HIV-testing services. Community-based and community-led models of service delivery (e.g. campaigns and home-based care) [37], HIV self-testing [38] and use of trained lay providers to conduct HIV testing need to be explored for the region. Countries also need to look at innovative strategies to create demand for HIV testing such as crowdsourcing, social media, peer-driven intervention, and incentive-based approaches for referring clients [28,39]. Additionally, expansion of laboratory capacities for early infant diagnosis and HIV testing in other settings/programmes is needed. HIV testing algorithms should be further simplified and streamlined to address losses at the first step of the HIV continuum of care [40].

Based on the results from the HPTN 052 [41], INSIGHT-START [42] and TEMPRANO trials [43], the WHO updated its treatment guidelines in 2015 to recommend immediate ART initiation [12]. While two countries in the region have taken up this recommendation, the majority of them recommend treatment initiation according to the WHO 2013 guidelines [17]. The implementation of national guidelines has been slow in the region and ART coverage remains low. Substantial challenges are related to limited financial resources, drug procurement and supply, cost of HIV care, human resource constraints and low HIV-testing rates [44–46]. Similarly, despite clear guidance, the scaling up of routine VL monitoring is lagging behind due to high costs, poor infrastructure and lack of training [47]. Achieving the 90-90-90 targets will require countries to move to treatment for all, and to provide routine treatment monitoring. Strong political commitment, financial resources and programme efficiency are needed to address the current challenges.

HIV programmes in all but a few countries remain heavily dependent on international funding, which is shrinking, unpredictable and risky. Furthermore, economic growth in a number of countries has resulted in the fact that they are no longer eligible for support from the Global Fund. Combined with a slow increase in domestic HIV spending and a further need of funding to achieve the 90-90-90 targets, there are serious concerns regarding transition management, financing mechanisms and sustainability of HIV programmes [48]. Governments need to look at innovative and sustainable funding mechanisms to increase domestic HIV spending and decrease their reliance on donors. There is also room for greater efficiency as countries will need to allocate their resources in policies and practices that will maximise cost-effectiveness.

In conclusion, the South-East Asia region has come a long way in its HIV response but there remain major gaps. Much needs to be done in order to strengthen and sustain this response in the context of universal health coverage in the post-2015 era of SDGs. Ending the HIV epidemic in the region will require that governments work in close collaboration with communities and key stakeholders and efficiently use their scarce resources to provide evidence-based HIV prevention and treatment interventions for populations in locations that need them most.

Acknowledgements

Disclaimer

The opinions and statements in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the official policy, endorsement or views of the WHO.

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1. WHO Regional Data Estimates 1990–2015.

- 2. United Nations Millennium Development Goals. Available at: www.mdgmonitor.org/mdg-6-combat-hiv-aids-malaria-and-other-diseases/ ( accessed November 2016).

- 3. UNAIDS How AIDS changed everything MDG 6: 15 years, 15 lessons of hope from AIDS response. 2015. Available at: www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/MDG6Report_en.pdf ( accessed November 2016).

- 4. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/ ( accessed November 2016).

- 5. UNAIDS AIDSInfo. Available at: http://aidsinfo.unaids.org/ ( accessed November 2016).

- 6. National AIDS Control Programme, Department of Health, Ministry of Health Country Progress Report on the HIV Response in Bhutan 2015. 2015. Available at: www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/BTN_narrative_report_2015.pdf ( accessed November 2016).

- 7. Ministry of Health Timor-Leste National AIDS Programme, UNAIDS Global AIDS Response Progress Report 2015. 2015. Available at: www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/TLS_narrative_report_2015.pdf ( accessed November 2016).

- 8. National AIDS Control Organization India India HIV Estimations 2015. Technical Report Available at: www.naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/India%20HIV%20Estimations%202015.pdf ( accessed November 2016).

- 9. Indonesia National AIDS Commission Indonesia Country Progress Report 2014. Available at: www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/IDN_narrative_report_2014.pdf ( accessed May 2016).

- 10. WHO SEAR Evaluation of the Regional Health Sector Strategy on HIV 2011–2015. In press.

- 11. UNAIDS Global AIDS Response Progress Reporting 2015. 2015. Available at: www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2702_GARPR2015guidelines_en.pdf ( accessed November 2016).

- 12. WHO Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Available at: www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/earlyrelease-arv/en/ ( accessed November 2016). [PubMed]

- 13. International Association of Providers of AIDS Care Global HIV Policy Watch [database online]. Updated 12 July 2016.

- 14. AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition (AVAC) Ongoing and Planned PrEP Demonstration and Implementation Studies [database online]. Updated June 2016. Available at: www.avac.org/resource/ongoing-and-planned-prep-demonstration-and-implementation-studies ( accessed November 2016).

- 15. Government of Nepal, Ministry of Health and Population, National Centre for AIDS and STD Control UNAIDS Country Progress Report 2015. Available at: www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/NPL_narrative_report_2015.pdf ( accessed June 2016).

- 16. Government of Maldives UNAIDS Country Progress Report 2015. Available at: www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/MDV_narrative_report_2015.pdf ( accessed June 2016).

- 17. WHO Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. 2013. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85321/1/9789241505727_eng.pdf ( accessed November 2016). [PubMed]

- 18. WHO Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents. 2010. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599764_eng.pdf ( accessed May 2016).

- 19. UNAIDS 90-90-90 An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2014. Available at: www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf ( accessed May 2016).

- 20. Mehta SH, Lucas GM, Solomon S et al. HIV care continuum among men who have sex with men and persons who inject drugs in India: barriers to successful engagement. Clin Infect Dis 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Becker ML, Mishra S, Satyanarayana, et al. Rates and determinants of HIV-attributable mortality among rural female sex workers in Northern Karnataka, India. Int J STD AIDS 2012; 23: 36– 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chakrapani V, Newman PA, Shunmugam M et al. Barriers to free antiretroviral treatment access for female sex workers in Chennai, India. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009; 23: 973– 980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jadhav A, Bhattacharjee P, Raghavendra T et al. Risky behaviors among HIV-positive female sex workers in northern Karnataka, India. AIDS Res Treat 2013; 2013: 878151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pendse R, Gupta S, Yu D. HIV testing as a bottleneck to elimination of mother to child transmission in the South-East Asia region. AIDS 2016. July 2016. Durban, South Africa. Abstract THPEC101. [Google Scholar]

- 25. UNAIDS Press Release Thailand is the first country in Asia to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of HIV and Syphilis. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2016/june/20160607_Thailand Accessed 19 June 2016.

- 26. News article Sri Lanka's Supreme Court makes landmark decision prohibiting HIV discrimination. 2 May 2016. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2016/may/20160502_Srilanka_nodiscrimination Accessed 11 May 2016.

- 27. Mabuchi S, Singh S, Bishnu R, Bennett S.. Management characteristics of successful public health programs: ‘Avahan’ HIV prevention program in India. Int J Health Plann Manage 2013; 28: 333– 345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bhattacharjee P, Prakash R, Pillai P et al. Understanding the role of peer group membership in reducing HIV-related risk and vulnerability among female sex workers in Karnataka, India. AIDS Care 2013; 25 Suppl 1: S46– 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hayashi K, Ti L, Avihingsanon A et al. Compulsory drug detention exposure is associated with not receiving antiretroviral treatment among people who inject drugs in Bangkok, Thailand: a cross-sectional study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2015; 10: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Heath AJ, Kerr T, Ti L et al. Healthcare avoidance by people who inject drugs in Bangkok, Thailand. J Public Health 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Logie CH, Newman PA, Weaver J et al. HIV-Related Stigma and HIV Prevention Uptake Among Young Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in Thailand. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016; 30: 92– 100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reid G, Sharma M, Higgs P.. The long winding road of opioid substitution therapy implementation in South-East Asia: challenges to scale up. J Public Health Res 2014; 3: 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sadhu S, Manukonda AR, Yeruva AR et al. Role of a community-to-community learning strategy in the institutionalization of community mobilization among female sex workers in India. PLoS One 2014; 9: e90592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sinha G, Dyalchand A, Khale M et al. Low utilization of HIV testing during pregnancy: what are the barriers to HIV testing for women in rural India? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 47: 248– 252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Woodford MR, Chakrapani V, Newman PA, Shunmugam M.. Barriers and facilitators to voluntary HIV testing uptake among communities at high risk of HIV exposure in Chennai, India. Glob Public Health 2015; 1– 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Diese M, Shrestha L, Pradhan B et al. Bottlenecks and opportunities for delivering integrated pediatric HIV services in Nepal. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016; 11: S21– 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sweat M, Morin S, Celentano D et al. Community-based intervention to increase HIV testing and case detection in people aged 16–32 years in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Thailand (NIMH Project Accept, HPTN 043): a randomised study. Lancet Infect Dis 2011; 11: 525– 532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tucker JD, Wei C, Pendse R, Lo YR.. HIV self-testing among key populations: an implementation science approach to evaluating self-testing. J Virus Erad 2015; 1: 38– 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. WHO Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations 2014. Case study: Online strategies to increase uptake of HTC services in Bangkok Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/128048/1/9789241507431_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 Accessed 11 May 2016. [PubMed]

- 40. Indrati AR, Crevel R, Parwati I et al. Screening and diagnosis of HIV-infection in Indonesia: one, two or three tests? Acta Med Indones 2009; 41 Suppl 1: 28– 32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 493– 505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Insight Start Study Group, Lundgren JD, Babiker AG et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 795– 807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Temprano ANTRS Study Group, Danel C, Moh R et al. A trial of early antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 808– 822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Riyarto S, Hidayat B, Johns B et al. The financial burden of HIV care, including antiretroviral therapy, on patients in three sites in Indonesia. Health Policy Plan 2010; 25: 272– 282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wasti SP, Simkhada P, Teijlingen ER.. Antiretroviral treatment programmes in Nepal: Problems and barriers. Kathmandu University Medical Journal 2009; 7: 306– 314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. News article India set to run out of critical free drug for HIV/AIDS programme. October 1 2014. Available at: http://in.reuters.com/article/aids-india-idINKCN0HQ3DU20141001 ( accessed November 2016).

- 47. Roberts T, Cohn J, Bonner K, Hargreaves S.. Scale-up of routine viral load testing in resource-poor settings: current and future implementation challenges. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62: 1043– 1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stuart RM, Lief E, Donald B et al. The funding landscape for HIV in Asia and the Pacific. J Int AIDS Soc 2015; 18: 20004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]