Abstract

Introduction

Postintensive care syndrome (PICS) is defined as a new or worsening impairment in cognition, mental health and physical function after critical illness. There is little evidence regarding treatment of patients with PICS; new directions for effective treatment strategies are urgently needed. Early physiotherapy may prevent or reverse some physical impairments in patients with PICS, but no systematic reviews have investigated the effectiveness of early rehabilitation on PICS-related outcomes. The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate whether early rehabilitative interventions in critically ill patients can prevent PICS and decrease mortality.

Methods

We will conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of early rehabilitation for the prevention of PICS in critically ill adults. We will search PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials for published randomised controlled trials. We will screen search results and assess study selection, data extraction and risk of bias in duplicate, resolving disagreements by consensus. We will pool data from clinically homogeneous studies using a random-effects meta-analysis; assess heterogeneity of effects using the χ2 test of homogeneity; and quantify any observed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. We will use the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach to rate the quality of evidence.

Discussion

This systematic review will present evidence on the prevention of PICS in critically ill patients with early rehabilitation.

Ethics

Ethics approval is not required.

Dissemination

The results will be disseminated via peer-reviewed journal publication, conference presentation(s) and publications for patient information.

Trial registration number

CRD42016039759.

Keywords: Post-Intensive Care Syndrome, Early rehabilitation, Sepsis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The current systematic review will assess the efficacy of early rehabilitation on patients with postintensive care syndrome (PICS) and will provide further clinical evidence for clinicians and patients.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study will be the first meta-analysis of comprehensive PICS based on the randomised controlled trials whose study intervention population was limited to early rehabilitation.

Some outcomes may include small number of patients and it can be high risk of biases.

Introduction

Dramatic developments and improvements in the tools and techniques used to provide life support to critically ill patients in intensive care units (ICUs) have reduced patient mortality.1 However, this evolution of life-saving interventions has resulted in increasing numbers of critically ill patient survivors with impaired physical and mental ability returning to usual life2 It is thus imperative that ICU care is managed with the goals of long-term patient health, wellness and functioning.1

Besides physiological impairments in surviving ICU patients, persistent mental and cognitive symptoms are problems that prevent them from being discharged home and, once home, from returning to usual daily life.2 3 In September 2010, the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) held a meeting of stakeholders from rehabilitation, outpatient and community care settings to develop an action plan to initiate improvements for ICU survivors, and their families, across the continuum of care.4 In the meeting, postintensive care syndrome (PICS) was stated as the term to describe ‘new or worsening impairments in physical, cognitive or mental health status arising after critical illness and persisting beyond acute care hospitalisation’.4 Post-ICU patients may experience physical problems, such as ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW), caused by a polyneuropathy and myopathy after ICU admission;3 5 dysphagia;6 cachexia or wasting syndrome;7 8 organ dysfunction;9 chronic pain;10 sexual dysfunction;11 12 mental health problems including depression, anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD);13 14 and neurocognitive impairments such as new or worsening cognitive impairment or delirium.15 The impact of these problems is reduced quality of life,14 16 17 reduced functional status2 18 and reduced daily functioning.2 3

Physiotherapy with early rehabilitation is seen as an integral component of the multidisciplinary management of patients in ICUs. Consistent with evidence that patients in ICUs may benefit from early mobilisation,4 19–23 the Pain, Agitation, and Delirium (PAD) clinical practice guidelines recommend mobilisation of patients in the ICU as soon as is feasible, to reduce the prevalence and duration of delirium and to improve functional outcomes. In 2013, Stiller24 published a systematic review investigating the effectiveness of physiotherapy for adult patients intubated and on mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Exercise in other populations has been shown to improve strength and function, decrease inflammation25–27 and affect oxidative stress;28–31 hence, it has been suggested that early physiotherapy for ICU patients may prevent or reverse some physical impairment. However, there is no systematic review investigating the effectiveness of early rehabilitation for the prevention of PICS in ICU patients. The purpose of this systematic review is to assess the effectiveness of early rehabilitative interventions for the prevention of PICS in ICU patients. This knowledge could direct further research in the field.

Methods

This review protocol has been registered in PROSPERO, an International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews at the National Institute for Health Research and Center for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) at the University of York (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/; Registration No. CRD42016039759).32 This protocol follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) statements,33 34 and the systematic review will be reported following PRISMA guidelines.33 35 36 PRISMA-P was described in online supplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2016-013828supp.pdf (148.9KB, pdf)

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) will be included and non-randomised and observational studies will be excluded. Restrictions on methodological quality of eligible RCTs will be imposed.

Types of participants

The population of interest is adult patients (aged over 18 years) admitted to the ICU. PICS criteria, namely acquired physical and psychiatric/cognitive dysfunction after ICU admission, will be identified using the PICS assessment scale (see ‘Types of outcome assessments’ section). We will exclude animal studies and studies with participants aged under 18 years (children, infants or neonates). We will also exclude patients with traumatic brain injury or stroke.

Types of interventions

The intervention of interest is early rehabilitation. ‘Early’ will be defined as (1) starting at an earlier point than usual care and (2) being conducted within 1 week of ICU admission. RCTs definitely described as ‘early’ will be included. ‘Rehabilitation’ will include all physiotherapy, occupational therapy and palliative care-related support.23

We will exclude RCTs in which rehabilitation is initiated before ICU admission. RCTs must include a control group which undergoes standard care or no early rehabilitation. We will also exclude RCTs comparing early rehabilitation with another intervention.

Types of outcome assessments

The primary outcomes of interest for this review are the following: (1) physical-related outcomes (incidence of ICU-AW, and standardised physical function-related scale combined 6 min walk test37 and the Medical Research Council scale;38 and (2) health and mental status-related outcomes, using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale39 and standardised Health Related Quality Of Life scale combined with the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Physical Function scale40 with EuroQol 5 Dimensions.41 42 Since exact PICS criteria do not exist, we will also evaluate overall outcomes after ICU discharge. The secondary outcomes are overall mortality (ICU-related or in-hospital) and adverse events.

Adverse events and complications evaluated will be the termination rate of early rehabilitation; plasma lactate levels and other complications, such as catheter removal, endotracheal tube removal, etc.

The Chelsea Critical Care Physical Assessment tool (CPAX),43 Physical Function in Intensive care Test (PFIT)44 and ICU Mobility Scale (IMS)45 are commonly used in the ICU and are useful tools for evaluating functional outcomes.46 However, we have chosen to use the 6 min walk test as the most reliable determinant of physical-related outcome in PICS, because we want to evaluate PICS in the ICU and also after discharge from the ICU.

Search methods for the identification of trials

A database search of PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) will be conducted to retrieve relevant articles for the literature review. We will search full-text clinical trials conducted in humans that were published between January 1970 and July 2016 in the English language only.

Data extraction and management

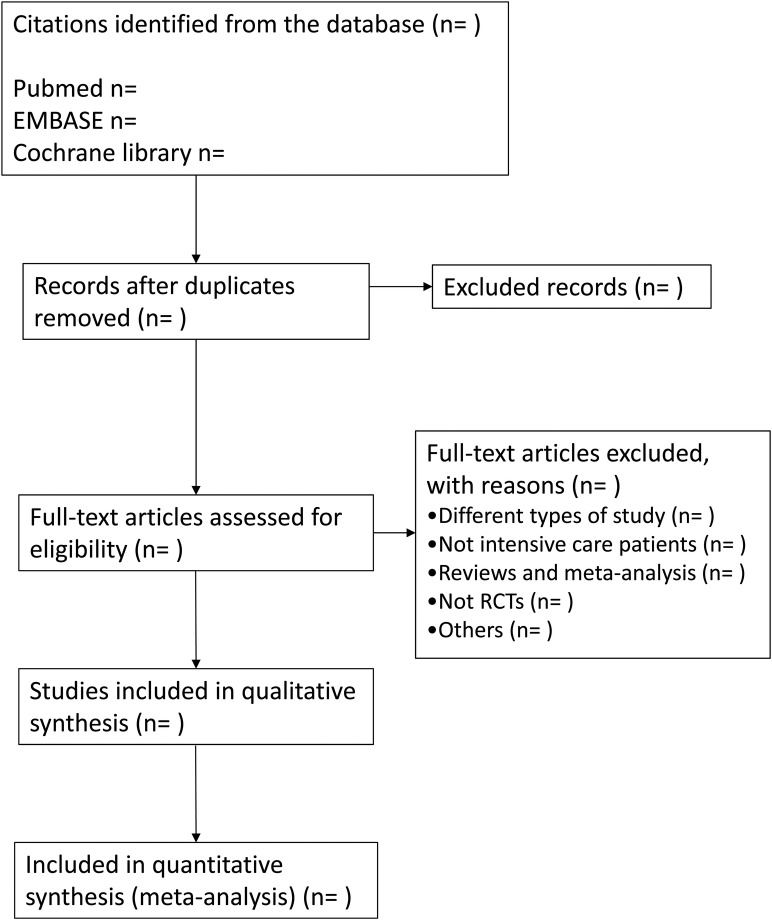

Data extraction: Author(s), title, journal name, year of publication, website URL and abstract will be identified. Conference abstracts will be excluded. The authors (YK, RF, SI) will perform the first-line comprehensive literature search and filter for duplicates. After duplicates are removed, two authors, randomly chosen from six authors (YK, RF, TH, JH, TT, SI), will independently screen study titles and abstracts for potential relevance in the primary selection process. When disagreement is identified between reviewers, the full text of the paper will be retrieved; disagreements will be again considered and discussed until consensus is reached. If disagreements cannot be reconciled, a third reviewer will be consulted. The full text of articles included in the final selection will be reviewed by two authors randomly chosen from six authors (YK, RF, TH, JH, TT, SI). The study flow diagram is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The primary selection process. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Assessment of risk of bias

To assess the quality of included studies, we will adapt the Cochrane risk of bias tool.47 Each study will be assessed for: (1) random sequence generation (selection bias); (2) allocation concealment (selection bias); (3) blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias); (4) blinding of related outcomes assessment (detection bias); (5) incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); (6) selective reporting (reporting bias) and (7) other bias. We will categorise studies as having a low, unclear or high risk of bias in each domain. Two independent reviewers, chosen from the six authors (YK, RF, TH, JH, TT, SI), will perform the risk of bias assessment, with disagreements resolved by discussion, and by third reviewer opinion if necessary. We will consider the risk of bias for each element to be ‘high’ when bias is present and likely to affect outcomes, and ‘low’ when bias is not present, or present but unlikely to affect outcomes.48 The κ coefficient will not be used for assessment of risk of bias for interobserver agreement between reviewers.

Summarising data and treatment effect

We plan to perform a meta-analysis when data are available in one or more trials according to the ‘Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions’ and PRISMA guidelines by using Review Manager software (RevMan V.5.3, Copenhagen, Denmark: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, the Cochrane Collaboration 2014). We will summarise the results of the meta-analysis using the generic inverse variance method to facilitate pooling of estimates of treatment effect. We will use ORs with 95% CIs for dichotomous outcomes, and mean differences or standardised mean differences with 95% CI for continuous outcomes, when appropriate. If quantitative synthesis is not appropriate for a particular outcome, we will provide a qualitative summary for that outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We will assess heterogeneity between trials for each outcome using the I2 statistic for quantifying inconsistency. We will consider that significant heterogeneity is present when the reason for heterogeneity cannot be explained and I2 is 50% or greater. If significant heterogeneity is found, the median of the estimates will be reported rather than a weighted, pooled estimate. Clinical heterogeneity will be explored by assessing differences in baseline data, types of early rehabilitation, definition of PICS and other outcome parameters. The presence of strong clinical heterogeneity will be considered in the decision to conduct quantitative synthesis of data or to perform sensitivity analyses with a special focus.49

Assessment of reporting bias

We will investigate the possibility of publication bias using a funnel plot. To test for funnel plot asymmetry, we will use the Egger test for continuous outcomes and the arcsine test for dichotomous outcomes, using STATA SE Statistical Software (Release V.13, College Station, Texas, USA: StataCorp LP).50 51

Data synthesis

Estimates will be pooled using a random-effects model. We are not planning to attempt to contact the primary trial authors for additional data. We will perform our analysis based on all published data or data made available to us.48

Subgroup analysis

We will also perform subgroup analyses to investigate the differences in pooled effect estimates related to different patient subgroups. We will test whether there is a differential intervention effect among the various subgroups with an interaction test, which is preferred over separate subgroup group-specific analyses. Subgroup analyses will be performed for the following variables:

Type and severity of conditions of patients in the ICU: a subgroup analysis will be necessary to investigate differences among categorised patients since we hypothesise that patients in the ICU have a variety of diseases and disease severity (such as sepsis, postoperative-related conditions, torso trauma and burn injuries).

Timing of initiation of early rehabilitation: we will conduct a subgroup analysis since there is potential for clinical heterogeneity in the variation in the timing of early rehabilitation.

Sensitivity analysis

To ensure the robustness of evidence, we will perform sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of studies with a high risk of bias. We will compare the results to decide whether lower quality studies should be excluded on the basis of sample size, strength of evidence or influence on pooled effective size.

Rating the quality of evidence using the GRADE approach

Two authors (RF and TH) will independently use the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) tool to rate the quality of the body of evidence. We will apply the GRADE approach to rate the quality of evidence of early rehabilitation for patient-important outcomes. Although the quality of evidence represents a continuum, we will assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome categorised as high, moderate, low or very low using the GRADE pro Guideline Development Tool.

Ethics and dissemination

This systematic review and meta-analysis protocol does not require ethics approval. The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis will be disseminated via publication in a peer-reviewed journal, presentations at conferences and publications for patient information.

Discussion

PICS has emerged in the past decade as a common and life-altering consequence of critical illness. Since then, it also has reported a lot of risks during hospitalisation.52 The effects of rehabilitation on PICS are unknown because there are a limited number of systematic reviews, and the concept of PICS is not widely used. In 2015, Castro-Avila et al53 conducted systematic review and meta-analysis, which are to discuss the effect of early rehabilitation for functional status in ICU patients. They did not have the concept of PICS and included all critically ill patients in the ICU, whereas we focus on only patients with PICS. We found 10 systematic reviews associated with rehabilitation and PICS,24 54–62 but only 1 used the SCCM definition of PICS.62 This previously reported systematic review suggested that symptoms of PTSD may be reduced by simple interventions such as ICU diaries, whereas most other outcomes are not improved. The review had several problems, notably that the interventions of included studies were mainly conducted in general wards or in outpatient departments, which may be too late for improving PICS. In addition, methodologically, this systematic review was unable to perform a meta-analysis.

Hence, our protocol is focused on early rehabilitation, and a meta-analysis has been considered in this study. In addition, many studies report favourable outcomes with early rehabilitation in postsurgical patients;63–65 however, the exact effect of early rehabilitation on the prevention of PICS is still unknown. This systematic review will present evidence on the prevention of PICS in critically ill patients with early rehabilitation.

Footnotes

Contributors: YK, RF, TH, JH, TT and SI conceived the idea for this systematic review. YK, RF, TH, JH, TT and SI developed the methodology for the systematic review and KY supervised the methodological process. The manuscript was drafted by YK and SI. RF, TH, JH, TT and KY supported the revision of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors will publish all relevant data collected as part of this study; however, readers are invited to contact the corresponding author if further information is desired.

References

- 1.Bemis-Dougherty AR, Smith JM. What follows survival of critical illness? Physical therapists’ management of patients with post-intensive care syndrome. Phys Ther 2013;93:179–85. 10.2522/ptj.20110429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM et al. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA 2010;304:1787–94. 10.1001/jama.2010.1553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit Care Med 2011;39:371–9. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fd66e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med 2012;40:502–9. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latronico N, Bolton CF. Critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy: a major cause of muscle weakness and paralysis. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:931–41. 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70178-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macht M, Wimbish T, Clark BJ et al. Post-extubation dysphagia is persistent and associated with poor outcomes in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care 2011;15:R231 10.1186/cc10472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pichard C, Thibault R, Heidegger CP et al. Enteral and parenteral nutrition for critically ill patients: a logical combination to optimize nutritional support. Clin Nutr Suppl 2009;4:3–7. 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.04.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid CL, Campbell IT, Little RA. Muscle wasting and energy balance in critical illness. Clin Nutr 2004;23:273–80. 10.1016/S0261-5614(03)00129-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Opal SM. Immunologic alterations and the pathogenesis of organ failure in the ICU. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2011;32:569–80. 10.1055/s-0031-1287865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmer A, Rothaug J, Mescha S. Chronic pain after surviving sepsis. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2006;23:235 10.1097/00003643-200606001-00844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffiths J, Gager M, Alder N et al. A self-report-based study of the incidence and associations of sexual dysfunction in survivors of intensive care treatment. Intensive Care Med 2006;32:445–51. 10.1007/s00134-005-0048-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ulvik A, Kvåle R, Wentzel-Larsen T et al. Sexual function in ICU survivors more than 3 years after major trauma. Intensive Care Med 2008;34:447–53. 10.1007/s00134-007-0936-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myhren H, Ekeberg Ø, Tøien K et al. Posttraumatic stress, anxiety and depression symptoms in patients during the first year post intensive care unit discharge. Crit Care 2010;14:R14 10.1186/cc8870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winters BD, Eberlein M, Leung J et al. Long-term mortality and quality of life in sepsis: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2010;38:1276–83. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d8cc1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torgersen J, Hole JF, Kvåle R et al. Cognitive impairments after critical illness. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2011;55:1044–51. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02500.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlsson S, Ruokonen E, Varpula T et al. Long-term outcome and quality-adjusted life years after severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2009;37:1268–74. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819c13ac [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oeyen SG, Vandijck DM, Benoit DD et al. Quality of life after intensive care: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med 2010;38:2386–400. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f3dec5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Schaaf M, Beelen A, Dongelmans DA et al. Functional status after intensive care: a challenge for rehabilitation professionals to improve outcome. J Rehabil Med 2009;41:360–6. 10.2340/16501977-0333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burtin C, Clerckx B, Robbeets C et al. Early exercise in critically ill patients enhances short-term functional recovery. Crit Care Med 2009;37:2499–505. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a38937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med 1999;340:669–76. 10.1056/NEJM199903043400901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris PE, Goad A, Thompson C et al. Early intensive care unit mobility therapy in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med 2008;36:2238–43. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180b90e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pohlman MC, Schweickert WD, Pohlman AS et al. Feasibility of physical and occupational therapy beginning from initiation of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 2010;38:2089–94. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f270c3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009;373:1874–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stiller K. Physiotherapy in intensive care: an updated systematic review. Chest 2013;144:825–47. 10.1378/chest.12-2930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gielen S, Adams V, Möbius-Winkler S et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of exercise training in the skeletal muscle of patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:861–8. 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00848-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nuhr MJ, Pette D, Berger R et al. Beneficial effects of chronic low-frequency stimulation of thigh muscles in patients with advanced chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2004;25:136–43. 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vivodtzev I, Pépin JL, Vottero G et al. Improvement in quadriceps strength and dyspnea in daily tasks after 1 month of electrical stimulation in severely deconditioned and malnourished COPD. Chest 2006;129:1540–8. 10.1378/chest.129.6.1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laaksonen DE, Atalay M, Niskanen L et al. Increased resting and exercise-induced oxidative stress in young IDDM men. Diabetes Care 1996;19:569–74. 10.2337/diacare.19.6.569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercken EM, Hageman GJ, Schols AMWJ et al. Rehabilitation decreases exercise-induced oxidative stress in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172: 994–1001. 10.1164/rccm.200411-1580OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishiyama Y, Ikeda H, Haramaki N et al. Oxidative stress is related to exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J 1998;135:115–20. 10.1016/S0002-8703(98)70351-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vincent HK, Morgan JW, Vincent KR. Obesity exacerbates oxidative stress levels after acute exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004;36:772–9. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000126576.53038.E9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D, Booth A, Stewart L. How to reduce unnecessary duplication: use PROSPERO. BJOG 2014;121:784–6. 10.1111/1471-0528.12657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:e1–34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pecorelli N, Fiore JF Jr, Gillis C et al. The six-minute walk test as a measure of postoperative recovery after colorectal resection: further examination of its measurement properties. Surg Endosc 2016;30:2199–206. 10.1007/s00464-015-4478-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paternostro-Sluga T, Grim-Stieger M, Posch M et al. Reliability and validity of the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale and a modified scale for testing muscle strength in patients with radial palsy. J Rehabil Med 2008;40:665–71. 10.2340/16501977-0235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Y, Ding R, Hu D et al. Reliability and validity of a Chinese version of the HADS for screening depression and anxiety in psycho-cardiological outpatients. Compr Psychiatry 2014;55:215–20. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang X, Fan D, Xia Q et al. The health-related quality of life of ankylosing spondylitis patients assessed by SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Life Res 2016;25:2711–23. 10.1007/s11136-016-1345-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Obradovic M, Lal A, Liedgens H. Validity and responsiveness of EuroQol-5 dimension (EQ-5D) versus Short Form-6 dimension (SF-6D) questionnaire in chronic pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:110 10.1186/1477-7525-11-110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mozzi A, Meregaglia M, Lazzaro C et al. A comparison of EuroQol 5-Dimension health-related utilities using Italian, UK, and US preference weights in a patient sample. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2016;8:267–74. 10.2147/CEOR.S98226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corner EJ, Wood H, Englebretsen C et al. The Chelsea critical care physical assessment tool (CPAx): validation of an innovative new tool to measure physical morbidity in the general adult critical care population; an observational proof-of-concept pilot study. Physiotherapy 2013;99:33–41. 10.1016/j.physio.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skinner EH, Berney S, Warrillow S et al. Development of a physical function outcome measure (PFIT) and a pilot exercise training protocol for use in intensive care. Crit Care Resusc 2009;11:110–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hodgson C, Needham D, Haines K et al. Feasibility and inter-rater reliability of the ICU Mobility Scale. Heart Lung 2014;43:19–24. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parry SM, Denehy L, Beach LJ et al. Functional outcomes in ICU—what should we be using?—an observational study. Crit Care 2015;19:127 10.1186/s13054-015-0829-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Higgins JPT AD, Sterne JAC, on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group and the Cochrane Bias Methods Group. Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies. Secondary Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies 2011.

- 48.Duan EH, Oczkowski SJ, Belley-Cote E et al. β-Blockers in sepsis: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised control trials. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012466 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klotz R, Klaiber U, Grummich K et al. Percutaneous versus surgical strategy for tracheostomy: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis of perioperative and postoperative complications. Syst Rev 2015;4:105 10.1186/s13643-015-0092-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4002 10.1136/bmj.d4002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davey Smith G, Egger M. Meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 1997;350:1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med 2013;368:100–2. 10.1056/NEJMp1212324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Castro-Avila AC, Serón P, Fan E et al. Effect of early rehabilitation during intensive care unit stay on functional status: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0130722 10.1371/journal.pone.0130722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adler J, Malone D. Early mobilization in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J 2012;23:5–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Calvo-Ayala E, Khan BA, Farber MO et al. Interventions to improve the physical function of ICU survivors: a systematic review. Chest 2013;144:1469–80. 10.1378/chest.13-0779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Choi J, Tasota FJ, Hoffman LA. Mobility interventions to improve outcomes in patients undergoing prolonged mechanical ventilation: a review of the literature. Biol Res Nurs 2008;10:21–33. 10.1177/1099800408319055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Govindan S, Iwashyna TJ, Odden A et al. Mobilization in severe sepsis: an integrative review. J Hosp Med 2015;10:54–9. 10.1002/jhm.2281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kayambu G, Boots R, Paratz J. Physical therapy for the critically ill in the ICU: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2013;41:1543–54. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827ca637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Z, Peng X, Zhu B et al. Active mobilization for mechanically ventilated patients: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94:551–61. 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moodie L, Reeve J, Elkins M. Inspiratory muscle training increases inspiratory muscle strength in patients weaning from mechanical ventilation: a systematic review. J Physiother 2011;57:213–21. 10.1016/S1836-9553(11)70051-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pinheiro AR, Christofoletti G. Motor physical therapy in hospitalized patients in an intensive care unit: a systematic review. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 2012;24:188–96. 10.1590/S0103-507X2012000200016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mehlhorn J, Freytag A, Schmidt K et al. Rehabilitation interventions for postintensive care syndrome: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2014;42:1263–71. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chiung-Jui Su D, Yuan KS, Weng SF et al. Can early rehabilitation after total hip arthroplasty reduce its major complications and medical expenses? Report from a nationally representative cohort. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:641958 10.1155/2015/641958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bugbee WD, Pulido PA, Goldberg T et al. Use of an anti-gravity treadmill for early postoperative rehabilitation after total knee replacement: a pilot study to determine safety and feasibility. Am J Orthoped 2016;45:E167–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Michot A, Stoeckle E, Bannel JD et al. The introduction of early patient rehabilitation in surgery of soft tissue sarcoma and its impact on post-operative outcome. Eur J Surg Oncol 2015;41:1678–84. 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.08.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013828supp.pdf (148.9KB, pdf)