Abstract

We report a case of a 76-year-old man, with the occasional finding of a mediastinal cyst because of subtle chronic dysphagia associated to sore throat, belching, and dysphonia. The paraesophageal cyst in the central mediastinum was studied with computed tomography (CT) scan and transesophageal three-dimensional (3D) echocardiography with contrast echo. In order to clarify doubts about localization (intra- versus extrapericardial) of the mediastinal cystic lesion the 3D transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) confirmed the presence of a large round cystic mass located contiguous to the esophagus, the left atrium and the aortic root/pulmonary trunk (located at the front of the lesion), as well as located intrapericardial. The cystic mass showed no blood flow at color Doppler mode and at ultrasound contrast echo with SonoVue agent. Due to the paucity of symptoms and to the definite imaging information of this intrapericardial cyst of nonvascular nature, due to pericardial cyst in an extremely unusual location, surgery was not performed. At follow-up of 1 month echocardiogram and 3 month CT scan the cyst appeared unchanged in dimensions.

Keywords: Contrast echocardiography, pericardial cyst, three-dimensional echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography

CASE REPORT

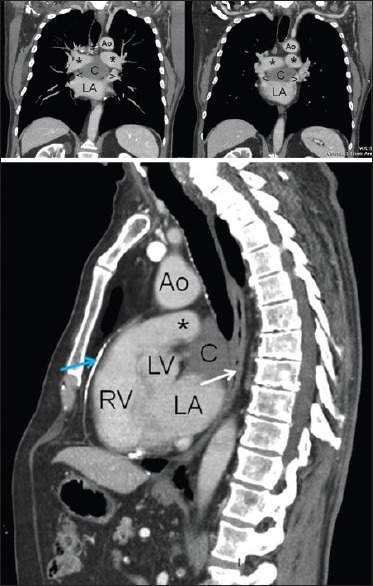

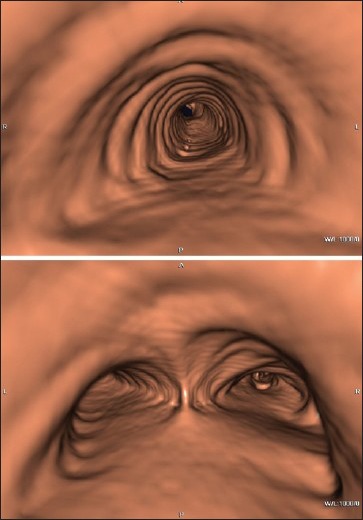

A 76-year-old Caucasian man with a family history of liver disease and polycystic liver disease, because of epigastric pain underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy showing stomach poorly distensible at the level of the body. A subsequent thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic contrast CT scan showed a rounded lesion, suprafluid-filled, with maximum transverse diameters of 62 mm × 35 mm in the middle mediastinum, at the level of subcarinal area, reported as a probable bronchogenic cyst — although it was not clear whether the lesion was intra- or extrapericardial [Figure 1]. Sequelae of calcific pericarditis were evident [Figure 1 bottom]. The 3D CT reconstruction as virtual bronchoscopy showed a perfect airway patency, with no evidence of extrinsic compression [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Thoracic contrast CT scan in coronal (top) and sagittal (bottom) reconstructions. Ao = aorta, C = cyst, LA = left atrium, LV = left ventricle, RV = right ventricle, * = pulmonary arteries, < and > = superior pulmonary veins, white arrow = esophagus, blue arrow = calcified pericardial plaque, CT = computed tomography

Figure 2.

Virtual bronchoscopy: Airway patency, with no evidence of extrinsic compression

Given the central position of the lesion within the mediastinum as well as the symptoms of the patient, a spirometry and a fiberoptic bronchoscopy were performed, in order to complete an assessment in view of a possible surgical removal of the cyst. Both exams showed no pathological findings.

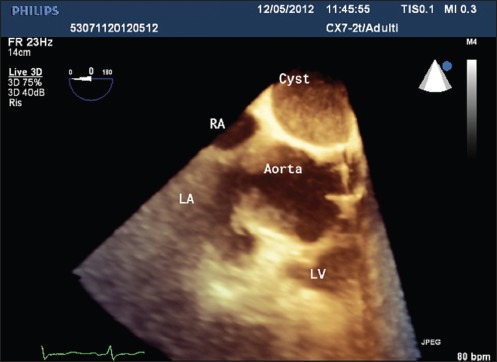

Therefore, echocardiography was performed for a complete functional diagnosis of the heart (intra-versus extrapericardial cyst localization) with transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) and transesophageal approach (TEE), with both 2D and 3D technique using a Philips IE 33 echo equipment (Eindhoven, Best, Netherlands) and a X7-2T probe (Philips, Eindhoven, Best, Netherlands; purchased with a grant from Cassa di Risparmio di Puglia foundation). For a better evaluation of both the perfusion and the kinetics of the flows, contrast echocardiography was performed using ultrasound contrast SonoVue (Bracco Imaging SpA, Milan, Italy), administered in two boluses of 1 cc intravenously followed by 2 cc of saline solution. TEE displayed the presence of a large round cystic mass, 51 mm × 38 mm in diameters [Figure 3, Video Clip 1]; the mass through 3D evaluation was located contiguous with the esophagus (located posterior to the cystic lesion), the left atrium (to the left of the lesion) and the aortic root/pulmonary trunk (located at the front of the lesion), as well as located intrapericardial. The cystic mass appeared to have a moderately echogenic content (more echogenic than blood and less echogenic compared to the myocardium), well-delineated limits, nonloculated cavity, thin, smooth, noncalcified walls, with no signs of echinococcosis [Figure 3, Video Clip 1]. Compared to the aortic root, the lesion was in close proximity to the common trunk of the right coronary artery, which did not exert compression on (coronary flow showed normal velocity of 25 cm/s, without acceleration and with normal systo/diastolic ratio).

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional TEE at 0°: Intrapericardial cystic mass with moderately echogenic content, well-delineated limits, nonloculated cavity; the walls of the cyst appear thin, smooth, noncalcified, with no signs of echinococcosis; relationships with other structures appear well-defined. LA = left atrium, LV = left ventricle, RA = right atrium, TEE = transesophageal echocardiography

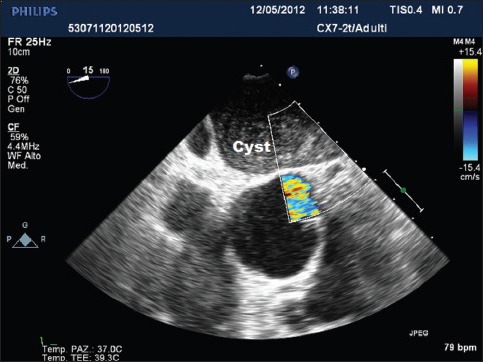

Moving blood was not observed within the lesion in color Doppler mode, even after reduction of the color scale [Figure 4]; moreover, ultrasound contrast agent arrival inside the cyst was not observed after intravenous infusion of SonoVue contrast agent [Figure 5].

Figure 4.

TTE at 15° in color Doppler mode: Absence of blood flow within the cystic lesion

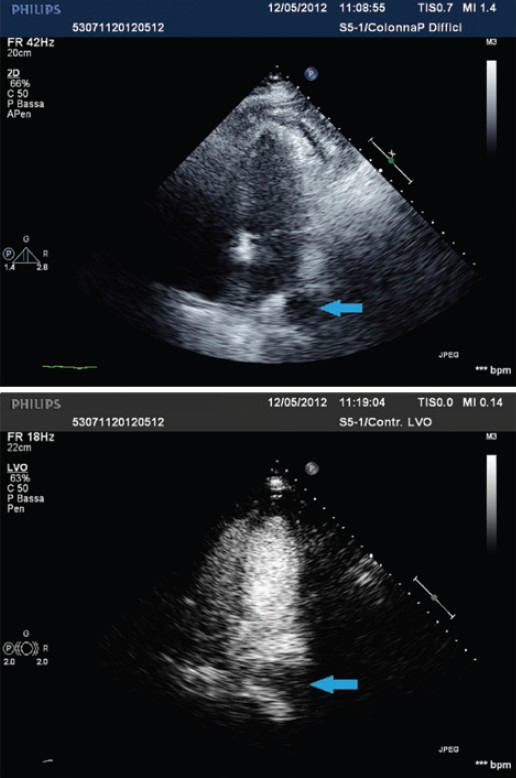

Figure 5.

Transthoracic echocardiography apical 4C views, before (upper panel) and after (lower panel) intravenous infusion of SonoVue echographic contrast: The contrast echo is not observed within the cystic lesion in any view (blue arrow)

Due to the paucity of symptoms and to the definite imaging information of this intrapericardial cyst of nonvascular nature, due to pericardial cyst in an extremely unusual location, surgery was not performed. At follow-up of 1 month echocardiogram and 3 month CT scan the cyst appeared unchanged in dimensions.

DISCUSSION

Pericardial pathology is commonly encountered in clinical practice and may present either as an isolated process or in association with other systemic disorders.[1] However, pericardial cysts are very rare, with an estimated prevalence of 1:100,000 persons,[2] constituting 7% of all mediastinal masses.[3] They are encapsulated structures most commonly located in the right anterior cardiophrenic angle, although they can be found throughout the mediastinum[1](right cardiophrenic angle 51-70%, left cardiophrenic angle 28-38%, and other mediastinal locations not adjacent to the diaphragm 8-11%). Generally congenital in origin, pericardial cysts are also occasionally seen after previous cardiac surgery.[1] They are often discovered incidentally on imaging studies, especially in the 4th or 5th decades of life.[2] The patient is frequently asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis; when symptoms occur, they are mainly due to the pressure of the cysts on adjacent organs.[3] Symptoms of atypical chest pain, dyspnea, paroxysmal tachypnea, and persistent cough are reported in about one-third of patients;[3] more rare are epigastric fullness, airway obstruction, asthma, venous obstruction, etc.[3] Possible complications are cyst rupture (leading to life-threatening pleural and pericardial effusion), erosion into adjacent structures, such as right ventricular wall or superior vena cava, cardiac tamponade or compression, mitral valve prolapse, obstruction of right main stem bronchus, and atrial fibrillation.[4,5]

Radiographically, these cysts abut the cardiac contours and are smooth-walled, round or irregularly shaped, with homogenous internal density.[5] The differential diagnoses of the pericardial cyst include teratoid cyst and tumor, cystic hygroma, primary or metastatic neoplasms, thymic lesions, cysts of foregut origin (bronchogenic cysts, esophageal duplications), granulomatous lesion, and abscess; besides other diseases (diaphragmatic hernia and aneurysms of the heart or great vessels).[5] Cardiac involvement of hydatid cyst is a very uncommon form of Echinococcus granulosus infestation (0.5-2% of all cases).[6] The most frequent cardiac localization of a hydatid cyst is the left ventricle because of its thickness and rich blood supply,[7] but rare cases of recurrent pericardial hydatid cysts have been reported.[8] In this eventuality, typical appearances of hydatid cyst in 2D echocardiography are double-layered, well-defined edges, and internal trabeculations.[8] It should also be also considered that an intrapericardial cystic lesion could be related to an encysted pericarditis, especially linked to the presence of systemic lupus erythematosus.[11]

Once suspected, the diagnosis can be established using noninvasive techniques. The imaging studies helpful in diagnosis are echocardiography, CT scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[3] The main indications and limitation for each test are summarized in Table 1. Echocardiography remains the initial imaging method of choice for the majority of patients with pericardial disease, but in many clinical scenarios, a TTE alone is insufficient.[1] TEE is considered a superior noninvasive modality to delineate the exact location of a pericardial cyst and to differentiate a cyst from other potential diagnoses such as fat pad, ventricular aneurysm, atrial appendage, aortic aneurysm, or a solid tumor.[3,10] Color Doppler is particularly helpful in differentiating a pericardial cyst from other vascular structures.[2] Pericardial cysts occur because of incomplete fusion of fetal mesenchymal lacunae forming the pericardium,[9] although it is important to recognize possible associated soft-tissue components that can be related to a malignant process; additional imaging by CT or cardiac MR is often helpful. A CT scan has been the modality of choice for diagnosis and follow-up; however, the diagnosis can be especially difficult if the lesion occurs outside the typical location (at the right cardiophrenic angle), or when the lesion is extensive and confluent with mediastinal structures (which is rare).[5] On CT, pericardial cysts typically appear as thin-walled, unilocular nonenhanced structures, with near water attenuation values.[1] Cardiac MR has a superior tissue characterization, important to recognize possible associated soft-tissue components that can be related to a malignant process. Cardiac MR is also recommended in the presence of contraindications to iodinate contrast.[1] The gross appearance of the excised pericardial cysts is represented by thin fibrous-walled structures. Their internal surfaces are uniformly smooth and usually contain serous fluid (so-called “spring water cysts”). As histopathology, the cyst wall is composed of a flat or cuboidal single layer of mesothelium and connective tissue.

Table 1.

Advantages and limitations of various imaging modalities in the evaluation of pericardial disease

| Indications and/or advantages | Limitations and/or disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography | First-line diagnostic imaging test in the evaluation and follow-up of pericardial disease | Limited windows, narrow field of view, in case of obesity, obstructive lung disease, or immediately post-cardiothoracic surgery |

| 3D TEE supplies better anatomic description | Operator-dependent | |

| Widely available with low cost | Limited tissue characterization | |

| No ionizing radiations | ||

| Can be performed bedside or in hemodynamically unstable patients | ||

| Cardiac CT | Performed whenever better anatomic description is needed | Use of ionizing radiation |

| Evaluation of associated and/or extracardiac disease | Use of iodinated contrast (unless visualization of related anatomy is not needed) | |

| Detection of pericardial calcification | Functional evaluation only possible with retrospectively gated studies (higher radiation dose, suboptimal temporal resolution) | |

| Difficulties in case of tachycardia or unstable heart rhythm (particularly for prospectively gated studies) | ||

| Need for breath-hold | ||

| Hemodynamically stable patients only | ||

| Cardiac MR | Performed whenever better anatomic description is needed | Time consuming |

| Superior tissue characterization | High cost | |

| Preferably stable heart rhythms | ||

| Contraindicated in case of pacemaker or defibrillators | ||

| Lung tissue less well visualized | ||

| Use of gadolinium contrast (renal dysfunction) | ||

| Use of some breath-hold sequences | ||

| Hemodynamically stable patients only |

CT = Computed tomography, MR = Magnetic resonance, 3D TEE = Three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography. Adapted from Verhaert et al., 2010

On echocardiography, pericardial cysts appear typically soft and unilocular (but sometimes they may be multilocular), with extremely variable dimensions up to 28 cm.[10] They are usually spherical or teardrop-shaped; cysts may be attached to the pericardium directly or by a pedicle, but they do not communicate with the pericardial space.[3] In the present case 3D TEE provided additional and more accurate details, both regarding the cyst itself (walls, content, signs of echinococcosis, and vascularization), both concerning its relations with the contiguous anatomical structures, without need of ionizing radiation or of hemodynamic stability of the patient.[1]

In the majority of cases pericardial cysts follow a benign course, therefore they usually need radiological and clinical follow-up only. When cysts are large or local complications occur (especially in case of cyst infection),[12 an interventional approach should be considered.[2] The various treatment modalities include percutaneous aspiration of cyst, ethanol sclerosis, surgical resection, or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.[5,13] Surgical excision becomes mandatory when pericardial cysts cause ventilatory and/or hemodynamic impairment.[3]

CONCLUSION

The diagnosis of dysontogenetic pericardial cyst in an extremely unusual location was possible without open chest surgery thanks to 3D transesophageal and contrast echography description of intrapericardial cystic mass of nonvascular nature (non-neoplastic), single-layered, without internal trabeculations (nonhydatid), unchanged along the time, in the absence of any clinical and laboratory sign of systemic lupus erythematosus.

Video available on www.jcecho.org

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, Lytle BW, Desai MY, Klein AL. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:333–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.921791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouzas-Mosquera A, Alvarez-García N, Peteiro J, Castro-Beiras A. Pericardial Cyst. Intern Med. 2008;47:1819–20. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Generali T, Garatti A, Gagliardotto P, Frigiola A. Right mesothelial pericardial cyst determining intractable atrial arrhythmias. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;12:837–9. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2010.261594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar S, Jain P, Sen R, Rattan K, Agarwal R, Garg S. Giant pericardial cyst in a 5-year-old child: A rare anomaly. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2011;4:68–70. doi: 10.4103/0974-2069.79629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pradder FA, Conrad AR, Manzar KJ, Thayapran N, Jonas EE, Freeman I. Echocardiographic diagnosis of pericardial cyst. Am J Med Sci. 1997;313:191–2. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nina VJ, Manzano NC, Mendes VG, Salgado Filho N. Giant pericardial cyst: Case report. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2007;22:349–51. doi: 10.1590/s0102-76382007000300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dighiero J, Canabal EJ, Aguirre CV, Hazan J, Horjales JO. Echinococcus disease of the heart. Circulation. 1958;17:127–32. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.17.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan M, Demitras M, Cimen S, Ozler A. Cardiac hydatic cysts with intracavary expansion. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1587–90. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02443-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akpinar I, Tekeli S, Sen T, Sen N, Basar N, Cagli KE, et al. Extremely rare cardiac involvement: Recurrent pericardial hydatid cyst. Intern Med. 2012;51:391–3. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.6370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozturk E, Aparci M, Haholu A, Sonmez G, Mutlu H, Basekim CC, et al. Giant, dumbbell-shaped pericardial cyst. Tex Heart Inst J. 2007;34:386–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaakik B, Benjelloun H. A rare pericardial cyst resembling hydatid cyst on echocardiography. Intern Med. 2010;49:1673–4. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thanneer L, Saric M, Perk G, Mason D, Kronzon I. A giant pericardial cyst. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1784. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abad C, Rey A, Feijoo J, Gonzales G, Martin-Suarez J. Pericardial cyst: Surgical resection in two symptomatic cases. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1996;37:199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.