Abstract

The quadricuspid aortic valve (QAV) is a rare malformation; often isolated, sometimes associated with other heart diseases. Before the era of echocardiography, the diagnosis was made incidentally at autopsy or during surgery of valve replacement. The extensive use of echocardiography has allowed an early and accurate diagnosis of this malformation. In many cases, the transthoracic approach is suitable for the diagnosis but, transesophageal echocardiography is a tool for the accurate definition of the valve anatomy. This review analyzes, after the presentation of a clinical case, the current knowledge on embryogenesis, classification, diagnosis and clinical course of QAV.

Keywords: Clinical course, diagnosis, echocardiography, quadricuspid aortic valve

INTRODUCTION

The quadricuspid aortic valve (QAV) is a very rare congenital anomaly, with a prevalence of 0.008% and 0.043% in autoptic and echocardiographic studies, respectively.[1,2,3] It is complicated with aortic insufficiency, with a slow and progressive evolution. Significant valvulopathy is often toward the fifth to sixth decade.[4]

Most frequently isolated, it is, sometimes, associated with other congenital heart defects. The extensive use of transthoracic (TTE) and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and systematic study of the aorta morphology allow an accurate detection of this anomaly.

This review was inspired by a clinical case of QAV came to our attention. Therefore, after the presentation of case report will be presented the current state of knowledge of this congenital heart disease. Will be discussed embryogenesis, anatomic variations, diagnostic process and the natural course of QAV.

CLINICAL CASE

A 63-year-old woman, suffering from systemic hypertension treated with beta-blockers; about 1-year palpitations was referred in our echolab to perform a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE).

On examination, her auscultation revealed a 2/6 diastolic aortic murmur, not signs of heart failure (no S3 or S4, no pulmonary rales, no peripheral edema).

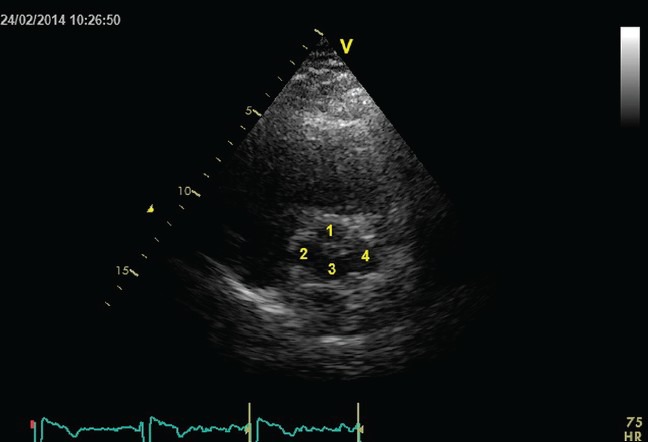

TTE showed normal left ventricular dimensions and function (ejection fraction: 64%). The normal size of aortic root and ascending aorta, the aortic valve had atypical morphology; on diastole the cusps closure appeared like an “X” for probable QAV [Figure 1]. We speculated an aortic cusps anomaly, but the acoustic window was not accurate to see closely the aortic valve. The color Doppler highlighted moderate aortic regurgitation.

Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiogram: At short-axis view, the aorta closure appears like a “X” with 4 cusps

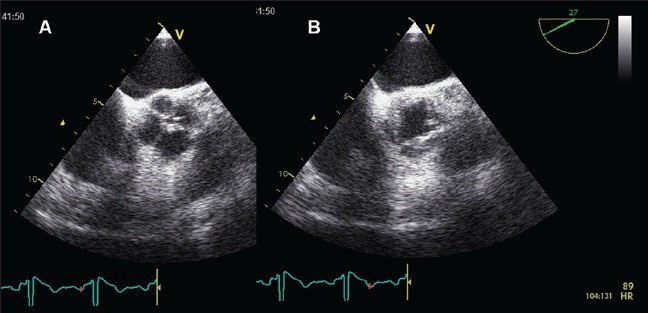

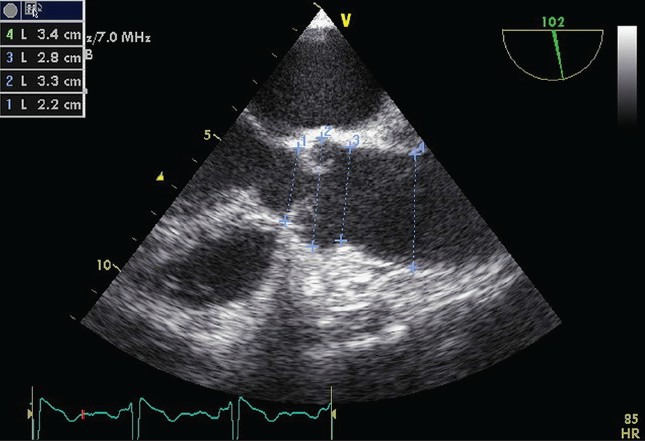

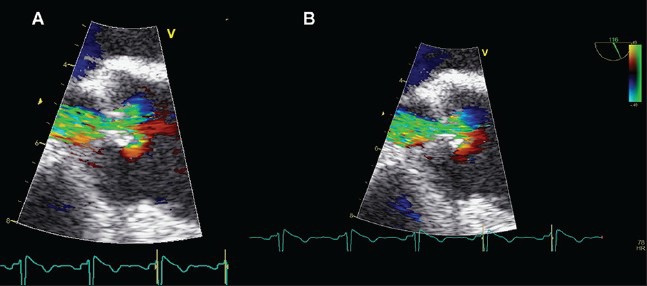

To better define the aortic morphology, we performed a TEE. The short-axis aortic view confirmed, on diastole, the cusps closure with an X-shaped instead of the usual Y-shaped appearance, in systole were clearly visualized 4 cusps with the valve opening similar to a “square.” All four cusps have equal size, were thickened and fibrous [Figure 2 and Video 1]. Long-axis view confirms the cusps thickening and highlights the normal size of the aortic apparatus and ascending aorta [Figure 3]. The color-Doppler confirmed the moderate aortic regurgitation with a central jet due to the failure of leaflets coaptation [Figure 4]. No other congenital heart anomalies.

Figure 2.

(a) Transesophageal echocardiography short-axis of the aorta: Diastolic closure of cusps is like an “X,” the sinuses of Valsalva are four, normal onset of coronary arteries. (b) in systole, the valve opens like a “square”

Figure 3.

Transesophageal echocardiography longitudinal view: The aorta has thickened leaflets with normal systolic excursion. The measures of the aortic apparatus and ascending aorta are normal

Figure 4.

Transesophageal echocardiography color Doppler: Flow turbulence created by fibrous aortic leaflets

Date the moderate degree of aortic regurgitation, normal ventricular diameters and left ventricular function the management of this case was for TTE follow-up and prophylaxis for infective endocarditis.

EMBRYOLOGY

The semilunar valves development starts during the 5 week, with two mesenchymal ridges that form the cephalic portion of the truncus arteriosus. These ridges fuse, descend into the ventricles and form the aortopulmonary septum. Each semilunar valve consists of three mesenchymal swelling that growing up, become excavated and form three cusps. This process is well advanced by week 6 and virtually complete by week 9.

The embryology of QAV remains unknown. Some mechanisms have been suggested: Such as anomalous septation of the conotruncus, excavation of one of the valve cushions, and septation of a normal valve cushion as a result of an inflammatory episode.[5,6,7,8] Some studies have suggested that QAV may result from the division of one of the three mesenchymal ridges that normally give rise to three aortic valve cushions.[9,10] They also demonstrated, at least in Syrian hamsters, that the division of the valve cushion starts at a very early stage of valve formation when the conotruncal ridges begin to fuse. The development of the aortic valve leaflets occurs temporally just after the formation process of the coronary artery origins from the sinuses of Valsalva.[11] For this reason, one could speculate that a single developmental abnormality might result in a variety of abnormalities in the aortic root. Therefore, abnormalities septation of aortic cusps could be embryologically related to abnormal growing of coronary arteries.

True QAVs must be distinguished from pseudo-QAVs resulting from bacterial endocarditis or rheumatic fever. To be considered a truly congenital malformation caused by abnormal embryogenesis, each cusp should contain a corpus Arantii.[6]

INCIDENCE

The bicuspid aortic valve is the most common aortic valve anomaly (2% of general population) followed by unicuspid aortic valve.[12,13] The truncal valve of truncus arteriosus is frequently quadricuspid but represents another congenital heart disease and is not subject of this review.[14]

The QAV is very rare. The first case described in the literature dates back to 1862 when Balington discovered it incidentally in the autoptic study.[15] The first in vivo description dating 1968, by Robicsek et al.[16]

The incidence of this anomaly is difficult to define and varies according to the modality of recognition and if this was specifically looked for. In autoptic series, Simonds diagnosed QAV in 0.008%; while in another study of 225 patients, Davia et al. not found QAVs.[5,17] In surgical studies Olson et al. observed an incidence of 1% in 225 patients undergoing to aortic valve replacement for pure aortic regurgitation; in contrast Turri et al. failed to find QAV on examination of 602 surgical specimens of aortic valve.[18,19]

More recently, echocardiographic studies showed an incidence slightly higher and equal to 0.043%.[2] This mismatch is not surprising since echocardiography allows a systematic study of the aortic valve, on larger and not complicated population; therefore, the ultrasound incidence seems to be closer to reality.

ANATOMIC VARIATIONS AND ASSOCIATED HEART DEFECT IN QUADRICUSPID AORTIC VALVE

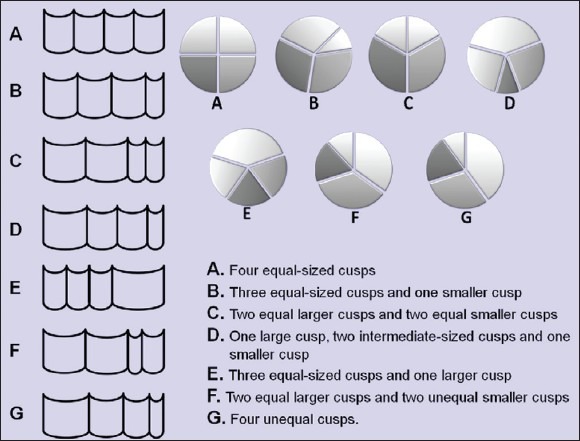

Although characterized by four cusps, the QAV presents anatomical variations, according to the cusp size. Hurwitz and Roberts, in their series of 97 patients, proposed a classification in seven subtypes universally accepted in all isolate clinical cases and small series published later [Figure 5].[7]

Figure 5.

Anatomic variations of QAV proposed by Hurwitz and Roberts. Left panel = Frontal view of cusps in different types of QAV, Top-right panel = Short-axis view of QAV, Bottom-right panel = Classification of different types. QAV = Quadricuspid aortic valve [from 7 adapted]

To date, three major series and many isolated cases have been published for a total of 271 patients; all cases are classified in the same way. Types A, B, and C are represented in more than 85%; while type D variant is very rare.[4]

Still now, is unknown whether this classification has only a morphological value or if, different types of QAV have distinct prognostic implications.

In general, QAV with four equal sized leaflets are less likely to develop fibrous thickening and significant aortic regurgitation while presence of an additional cusp smaller than other, could develop unequal distribution of stress, fibrosis and abnormal coaptation, facilitating a significant regurgitation.[20] This hypothesis seems the most likely, although other mechanisms could be possible.

The QAV usually appears as an isolated congenital anomaly, but may also be associated with other heart conditions. The most common is the abnormally placed ostia (10% of cases) involving both in left and right coronaries.[21,22,23] Others cardiac anomalies are ventricular septal defect, hypertrophic nonobstructive cardiomyopathy, pulmonary valve stenosis, patent ductus arteriosus, subaortic fibromuscolar stenosis, supravalvular stenosis with left coronary artery atresia and mitral valve malformation.[3,7,22,24,25,26,27,28]

DIAGNOSIS

The extensive use of echocardiography, harmonic imaging, full digital equipment and transesophageal approach allowed to verify the diagnosis of QAV earlier and in a greater number of cases, than surgical or autoptic series. Typically, the QAV is recognizable in many cases with TTE. The short-axis view at the aorta level allows accurate visualization of number, thickening and mobility of the aortic cusps; classical pattern is a “X-shaped” commissural aortic valve in diastole compared to the “Y” in the trileaflets. The color Doppler evaluates presence and severity of aortic regurgitation.

In some cases, TTE fails the diagnosis but, at least, raises the suspicion of anomalous cusps (often for the bicuspid aorta). In these cases, TEE is an accurate tool to define the diagnosis, demonstrate the four cusps, their size, ranking variant QAV, and visualize the possible displacement of coronary ostia.[29,30,31] Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have a very high diagnostic value, but their use in clinical practice is not advised.[32,33]

Prompt detection of QAV is important since it evolves to aortic regurgitation which while rare in children and adolescents, in adults may require surgical treatment.

Natural history

The relative small number of QAV reported in the literature does not allow definite conclusions about the natural history.

This anomaly has been frequently associated with aortic regurgitation (75% of cases), normal aortic valve function was reported in 16% of QAV patients while valvular stenosis is uncommon.[22]

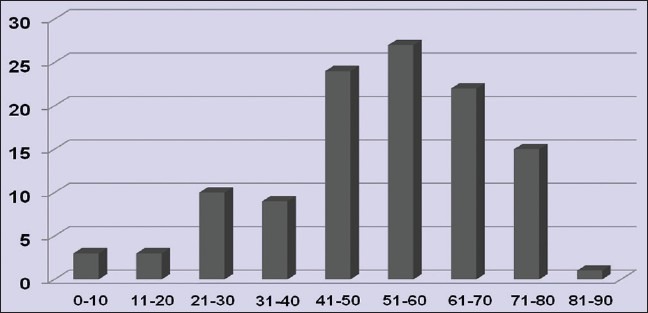

Progression to moderate-severe regurgitation is rare before adulthood; the largest review published included 186 patients, aged between 2 and 84 years; in this series, the highest incidence of normal valve function was in patients under 18 years and worsening function after 40 years.[22] The higher prevalence of severe aortic regurgitation (75% of cases) and surgery (50% of aortic regurgitation) is in the fifth or sixth decade [Figure 6].[3,4,22]

Figure 6.

Age distribution of QAV. QAV = Quadricuspid aortic valve [from 4 adapted]

Unlike bicuspid aortic valve, QAV is not associated to ascending aorta dilatation. In fact, in almost of cases reported, aortic root, and ascending aorta were within normal limits. This data has clinical and management significance.

There is no significant sex preference with regards to QAV distribution but only a slight male predominance.[7,22]

Infective endocarditis was found in 1.4% of cases. Therefore, prophylaxis is advised.[7,34,35,36,37]

In a not negligible number of cases (about 10%) QAV is associated with abnormal placed coronary ostia. This not clinically harmful anomaly has practical importance for surgical intervention to guide the surgeon to the most appropriate approach. In literature were published cases of deaths as a result of coronary ostium obstruction by a prosthetic aortic ring.[32]

DISCUSSION

In the present knowledge on QAV, the clinical case reported is representative for anatomical features and natural history. The patient was asymptomatic until the sixth decade, QAV was the most common variant (type A with four equal cusps), aortic regurgitation was due to cusps fibrosis and the aortic root and ascending aorta were normal. Our case confirms the screening value of TTE in suspicion of aortic valve cusps anomaly, and the accurate diagnostic role of TEE in QAV.

QAV is a rare anomaly. Its incidence varies from 0.008% to 0.043% based on the diagnostic modality. Furthermore, the incidence of echocardiographic series is underestimated, but certainly, closer to the real world.

More frequently QAV is an isolated finding, but may be associated with other random heart lesions. The most frequent and dreaded coexisting injury is the anomalous placed coronary ostia, secondary to the possible different position of the Valsalva sinuses than in aortic tricuspid valve.

Echocardiography is a very accurate technique for the diagnosis. TTE allows in many cases the diagnosis and sets the severity of aortic regurgitation, left ventricular size and function, the presence of associated cardiac lesions and ascending aorta size. TEE, however, is a more sensitive tool that defines all details unclear at TTE and visualizes correctly the coronary ostia.

The QAV is one cause of significant aortic regurgitation that is the predominant clinical finding; recognize it is particularly important for surgical management. In fact, from viewpoint of the surgeon, it is important to notice any displacement of the coronary ostia in order to prevent ostial obstruction at the time of valve replacement or repair.

Unlike bicuspid aortic valve, QAV not seems associated to ascending aorta dilatation.

CONCLUSION

The systematic TTE study of the aortic valve should consider not only the bicuspid aortic valve but also the QAV. This anomaly, although rare, has a different clinical impact; aortic regurgitation, abnormal placed coronary ostia and the absence of ascending aortic dilatation seem to be the key features.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Video files available on www.jcecho.org

REFERENCES

- 1.Yotsumoto G, Iguro Y, Kinjo T, Matsumoto H, Masuda H, Sakata R. Congenital quadricuspid aortic valve: Report of nine surgical cases. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;9:134–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman BJ, Khandheria BK, Warnes CA, Seward JB, Taylor CL, Tajik AJ. Incidence, description and functional assessment of isolated quadricuspid aortic valves. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:937–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)91446-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Timperley J, Milner R, Marshall AJ, Gilbert TJ. Quadricuspid aortic valves. Clin Cardiol. 2002;25:548–52. doi: 10.1002/clc.4950251203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jagannath AD, Johri AM, Liberthson R, Larobina M, Passeri J, Tighe D, et al. Quadricuspid aortic valve: a report of 12 cases and a review of the literature. Echocardiography. 2011;28:1035–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2011.01477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonds JP. Congenital malformation of the aortic and pulmonary valves. Am J Med Sci. 1923;166:584–95. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peretz DI, Changfoot GH, Gourlay RH. Four-cusped aortic valve with significant hemodynamic abnormality. Am J Cardiol. 1969;23:291–3. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(69)90081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurwitz LE, Roberts WC. Quadricuspid semilunar valve. Am J Cardiol. 1973;31:623–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(73)90332-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salvatore L, Mincione G, Baldelli P. Quadriscuspid aortic valve with aortic regurgitation. Report of an angiographically detected case (author's transl) G Ital Cardiol. 1976;6:323–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernández B, Durán AC, Martire A, López D, Sans-Coma V. New embryological evidence for the formation of quadricuspid aortic valves in the Syrian hamster (Mesocricetus auratus) J Comp Pathol. 1999;121:89–94. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.1998.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernández B, Fernández MC, Durán AC, López D, Martire A, Sans-Coma V. Anatomy and formation of congenital bicuspid and quadricuspid pulmonary valves in Syrian hamsters. Anat Rec. 1998;250:70–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199801)250:1<70::AID-AR7>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bogers AJ, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Poelmann RE, Péault BM, Huysmans HA. Development of the origin of the coronary arteries, a matter of ingrowth or outgrowth? Anat Embryol (Berl) 1989;180:437–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00305118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts WC. The congenitally bicuspid aortic valve. A study of 85 autopsy cases. Am J Cardiol. 1970;26:72–83. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(70)90761-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falcone MW, Roberts WC, Morrow AG, Perloff JK. Congenital aortic stenosis resulting from a unicommisssural valve. Clinical and anatomic features in twenty-one adult patients. Circulation. 1971;44:272–80. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.44.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collett RW, Edwards JE. Persistent truncus arteriosus; a classification according to anatomic types. Surg Clin North Am. 1949;29:1245–70. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)32803-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balington J. London Medical Gazetta. 1862 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robicsek F, Sanger PW, Daugherty HK, Montgomery CC. Congenital quadricuspid aortic valve with displacement of the left coronary orifice. Coll Works Cardiopulm Dis. 1968;14:87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davia JE, Fenoglio JJ, DeCastro CM, McAllister HA, Jr, Cheitlin MD. Quadricuspid semilunar valves. Chest. 1977;72:186–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.72.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olson LJ, Subramanian R, Edwards WD. Surgical pathology of pure aortic insufficiency: A study of 225 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:835–41. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65618-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turri M, Thiene G, Bortolotti U, Milano A, Mazzucco A, Gallucci V. Surgical pathology of aortic valve disease. A study based on 602 specimens. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1990;4:556–60. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(90)90145-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Aloia A, Vizzardi E, Bugatti S, Chiari E, Repossini A, Muneretto C, et al. A quadricuspid aortic valve associated with severe aortic regurgitation and left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:724–5. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balington J, quoted by Robicsek F, Sanger PW, Daugherty HK. Montgomery CC: Congenital quadricuspid aortic valve with displacement of the left coronary orifice. Coll Works Cardiopulm Dis. 1968;14:87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tutarel O. The quadricuspid aortic valve: A comprehensive review. J Heart Valve Dis. 2004;13:534–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robicsek F, Sanger PW, Daugherty HK, Montgomery CC. Congenital quadricuspid aortic valve with displacement of the left coronary orifice. Am J Cardiol. 1969;23:288–90. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(69)90080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssens U, Klues HG, Hanrath P. Congenital quadricuspid aortic valve anomaly associated with hypertrophic non-obstructive cardiomyopathy: A case report and review of the literature. Heart. 1997;78:83–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Possati F, Calafiore AM, Di Giammarco G, Romolo MB, Gaeta F, Gallina S, et al. Quadricuspid aortic valve and pulmonary valve stenosis. A rare combination in the adult. Minerva Cardioangiol. 1984;32:815–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iglesias A, Oliver J, Muñoz JE, Nuñez L. Quadricuspid aortic valve associated with fibromuscular subaortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation treated by conservative surgery. Chest. 1981;80:327–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.80.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zacharaki AA, Patrianakos AP, Parthenakis FI, Vardas PE. Quadricuspid aortic valve associated with non-obstructive sub-aortic membrane: A case report and review of the literature. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2009;50:544–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenkranz ER, Murphy DJ, Jr, Cosgrove DM., 3rd Surgical management of left coronary artery ostial atresia and supravalvar aortic stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;54:779–81. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)91031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayakawa M, Asai T, Kinoshita T, Suzuki T. Quadricuspid aortic valve: A report on a 10-year case series and literature review. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;20(Suppl):941–4. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.13-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe T, Hosoda Y, Sasaguri S, Aikawa Y. A quadricuspid aortic valve diagnosed by transesophageal echocardiography: Report of a case. Jpn J Surg. 1998;28:1102–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02483973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai CP, Koyanagi S, Sadoshima J, Takeshita A, Tokunaga K. Transesophageal echocardiographic findings of quadricuspid aortic valve. Jpn Heart J. 1991;32:731–4. doi: 10.1536/ihj.32.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kajinami K, Takekoshi N, Mabuchi H. Images in cardiology. Non-invasive detection of quadricuspid aortic valve. Heart. 1997;78:87. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu J, Zhang J, Wu S, Zhang Y, Ding F, Mei J. Congenital quadricuspid aortic valve associated with aortic insufficiency and mitral regurgitation. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;8:87. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-8-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawanishi Y, Tanaka H, Nakagiri K, Yamashita T, Okada K, Okita Y. Congenital quadricuspid aortic valve associated with severe regurgitation. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2008;16:e40–1. doi: 10.1177/021849230801600522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsukawa T, Yoshii S, Hashimoto R, Muto S, Suzuki S, Ueno A. Quadricuspid aortic valve perforation resulting from bacterial endocarditis-2-D echo- and angiographic diagnosis and its surgical treatment. Jpn Circ J. 1988;52:437–40. doi: 10.1253/jcj.52.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeda N, Ohtaki E, Kasegawa H, Tobaru T, Sumiyoshi T. Infective endocarditis associated with quadricuspid aortic valve. Jpn Heart J. 2003;44:441–5. doi: 10.1536/jhj.44.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bauer F, Litzler PY, Tabley A, Cribier A, Bessou JP. Endocarditis complicating a congenital quadricuspid aortic valve. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2008;9:386–7. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.