Abstract

Multiple signalling events interact in cancer cells. Oncogenic Ras cooperates with Egfr, which cannot be explained by the canonical signalling paradigm. In turn, Egfr cooperates with Hedgehog signalling. How oncogenic Ras elicits and integrates Egfr and Hedgehog signals to drive overgrowth remains unclear. Using a Drosophila tumour model, we show that Egfr cooperates with oncogenic Ras via Arf6, which functions as a novel regulator of Hh signalling. Oncogenic Ras induces the expression of Egfr ligands. Egfr then signals through Arf6, which regulates Hh transport to promote Hh signalling. Blocking any step of this signalling cascade inhibits Hh signalling and correspondingly suppresses the growth of both, fly and human cancer cells harbouring oncogenic Ras mutations. These findings highlight a non-canonical Egfr signalling mechanism, centered on Arf6 as a novel regulator of Hh signalling. This explains both, the puzzling requirement of Egfr in oncogenic Ras-mediated overgrowth and the cooperation between Egfr and Hedgehog.

EGFR signalling is required for oncogenic Ras driven tumorigenesis. In this study, using a Drosophila tumour model the authors demonstrate that depletion of Arf6, a Ras-related GTP-binding protein activated by EGFR, supresses oncogenic Ras driven overgrowth via modulation of Hedgehog signalling.

Activating mutations of the Ras gene are highly prevalent in human cancers and give rise to some of the most aggressive tumours1. The molecular mechanisms governing oncogenic Ras-driven cancers are complex and involve interacting signalling pathways1,2. Paradoxically, oncogenic Ras cooperates with Egfr in cancers3,4,5,6. EGFR ligands bind to and activate Egfr, which recruits docking proteins via its cytoplasmic domain. Docking proteins (such as the downstream of receptor kinases or drk) activate the guanine exchange factor Son of sevenless (Sos), which converts Ras from an inactive (GDP-bound) to an active (GTP-bound) state and leads to the MAPK signalling cascade and activation of downstream target molecules7,8. It is surprising that the action of an activated downstream oncogenic component still requires its upstream receptor.

On the other hand, Egfr has been shown to cooperate with Hedgehog (Hh) signalling, another oncogenic pathway, to drive basal cell carcinoma and melanomas9,10,11,12. Hh signalling is initiated by the interaction of Hh protein with its receptor Patched. Endocytosis and intracellular transport of the receptor–ligand complex modulate Hh signalling levels13. How oncogenic Ras, Egfr and Hh signalling are integrated to concertedly drive tumour overgrowth remains unclear. Animal models expand our understanding of oncogenic Ras signalling.

Using a fly tumour model of oncogenic Ras we have identified Egfr as a positive regulator of oncogenic Ras-mediated overgrowth. Our characterization of Egfr's role in oncogenic Ras-mediated overgrowth led the finding that oncogenic Ras signalling stimulates the expression of the Egfr ligand spitz (spi) to recruit Egfr signalling and achieve tumour overgrowth. Egfr promotes tumour overgrowth independent of the canonical the Sos/Ras signalling, instead it acts via the ADP-Ribosylation Factor 6 (Arf6). Arf6 belongs to a family of highly conserved small Ras-related GTP-binding proteins and is largely known for its role in regulating endocytosis, vesicle transport and secretion14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. We investigated a role for Arf6 in oncogenic Ras tumour overgrowth and found that Egfr promotes Arf6 to interact with Hh. This interaction allows Arf6 to control Hh cellular trafficking and promote Hh signalling. Consistent with this, blocking Egfr or Arf6 suppresses Hh signalling and inhibits the growth of either fly or human cancer cells harbouring oncogenic Ras. Altogether, our data delineate a non-canonical Egfr signalling mechanism in which Arf6 acts as a novel regulator of Hh signalling. This explains the puzzling requirement of Egfr in oncogenic Ras-mediated overgrowth and the oncogenic cooperation between Egfr and Hh signalling.

Results

Egfr − suppresses RasV12 tumours by inhibiting cell proliferation

Mosaic expression of oncogenic Ras (RasV12) gives rise to hyperplastic tumours in Drosophila tissues23,24. These tumours can be GFP-labelled and a measure of the overgrowth phenotype can be readily obtained by examining the size and the fluorescence intensity of clones in dissected eye-antenna imaginal discs from third-instar animals25,26 (Fig. 1a,b,f and g). We searched for mutations that suppress RasV12 tumour overgrowth26 and identified a null Egfr mutation EgfrCo (ref. 27), hereafter referred to as Egfr_. We generated clones of cells harbouring the Egfr_ mutation or expressing RasV12 in the presence of the Egfr_ mutation and scored clones size. Consistent with EGFR's known role in controlling cell survival and growth28, Egfr_ mutant cells yielded small clones (Fig. 1a,c,f and h). We found that Egfr_ suppressed RasV12 tumour overgrowth (Fig. 1a,b,d,f,g and i; quantified in Fig. 2j). A dominant-negative version of Egfr (lacking its cytoplasmic tail)29 produced a similar effect (Fig. 1e,j). Thus oncogenic Ras-mediated overgrowth requires the function of the upstream receptor Egfr.

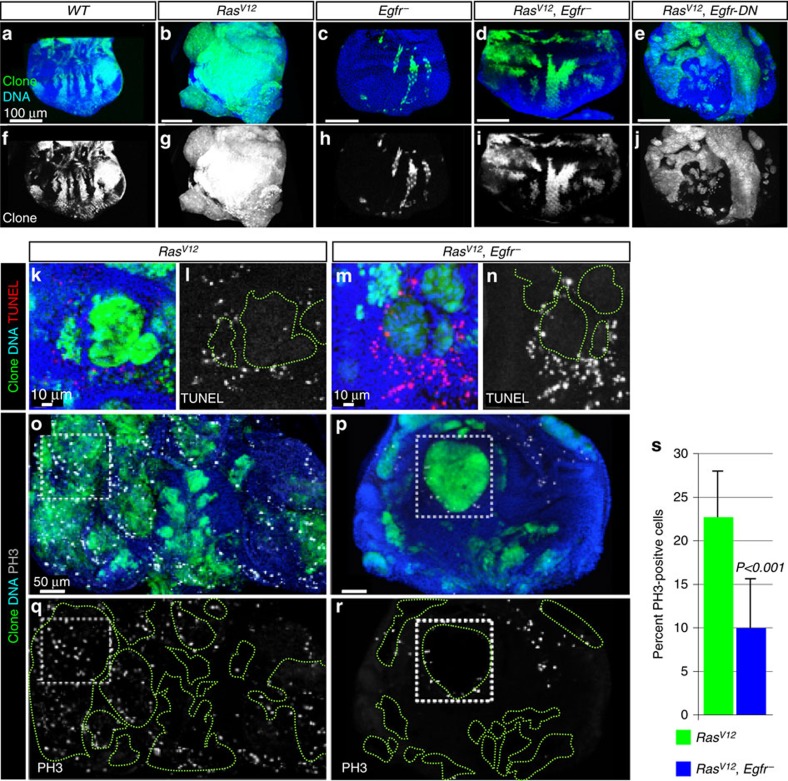

Figure 1. Egfr− suppresses RasV12 tumour overgrowth by inhibiting cell proliferation.

(a–j) Images of eye discs containing GFP-labelled wild-type or RasV12 or Egfr− single mutant or RasV12, Egfr− or RasV12, Egfr-DN double mutant clones dissected from wondering third-instar animals raised at 25 °C. Images represent a projection of the top 10 μm for each genotype. RasV12 clones (b) overgrow to form large contiguous tumours compared with control clones (a). The Egfr− mutation yields small clones (c) and suppresses the growth of RasV12 clones (d). Expression of a dominant version of Egfr (Egfr-DN) similarly suppresses RasV12 tumour growth (e). Respective GFP (clones) channels are shown in the bottom panels (f–j). (k–n) Representative images showing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) dUTP nick-end labelling (TUNEL) of RasV12 or RasV12, Egfr− double mutant clones to detect apoptotic cells. RasV12, Egfr− double mutant clones (m,n) do not show ectopic cell death compared to RasV12 clones (k,l). (o–r) Representative eye discs showing RasV12 (o) or RasV12, Egfr− double mutant (p) clones stained with anti-phosphohistone3 (PH3) antibodies to detect mitotic cells. Boxed areas are shown for comparison. Individual PH3 channels are shown in q,r. (s) Quantitation of o–r. The number of PH3-positive over total number of cells was scored in multiple clones across several animals for each genotype. The Egfr− mutation reduced the percentage of proliferative cells (Mean±s.d.%, N, P: 9.97±5.6%, N=1,693 cells from 7 discs, P<0.001 versus 27.7±5.2%, N=2,100 cells from 11 discs for RasV12 and RasV12, Egfr− double mutant cells, respectively). Error bars represent standard deviation (s.d.) from the mean for each genotype analysed. P is derived from t-test analyses and N denotes the sample size.

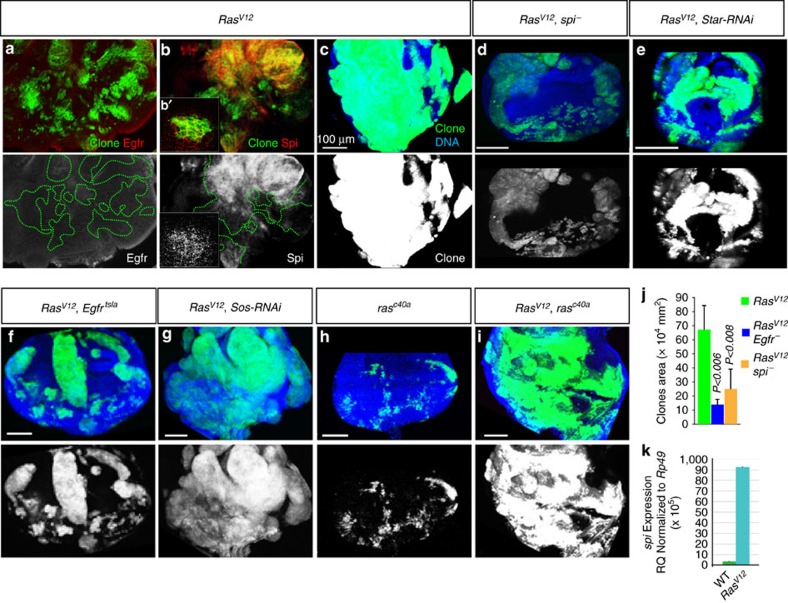

Figure 2. Oncogenic Ras upregulates the expression of the EGFR ligand Spitz to stimulate tumour overgrowth independent of canonical EGFR signalling.

(a–b') Early third-instar eye discs showing RasV12 clones (green) stained with anti-Egfr or anti-spitz antibodies (red). Egfr protein levels remain unchanged in RasV12 clones (a), while spitz is specifically elevated in RasV12 clones and can be detected around some clones (b,b'). (c–i) Eye discs dissected from wondering third-instar animals showing clone growth for cells expressing RasV12 in otherwise wild-type background (c) or in cell carrying spi− (d) or Egfrtlsa (f) mutations or co-expressing Star-RNAi (e) or Sos-RNAi (g) or carrying the rasc40a (i) mutation. h is showing the growth of rasc40a clones in similarly aged animals. To the exception of RasV12, Egfrtlsa animals, which were raised at 29 °C, all animals were raised at 25 °C. spi− (d) Star-RNAi (e) and Egfrtlsa (f), but not Sos-RNAi (g), suppress the overgrowth of RasV12 clones (b). Similarly, rasc40a produced small clones (h) but fail to suppress the overgrowth of RasV12 tumour overgrowth (i). (j) Clone size quantitation. For this and all the subsequent clone size measurements, confocal stacks from similarly aged animal of the indicated genotypes and the image analysis software Imaris were used to measure clones areas. Mean±s.d.%, N, P: 13.8±3.5 × 104, N=134 clones, P<0.006 (RasV12, Egfr− double mutant clones) or 24.9±13.8 × 104, N=91 clones, P<0.008 (RasV12, spi− double mutant clones) versus 67.1±16.8 × 104, N=20 clones (RasV12 clones). (k) Reverse transcription PCR experiment measuring spi levels relative to expression levels of the housekeeping gene Rp49. Normalized fold differences of spi expression levels in eye discs bearing wild-type versus RasV12 clones. Experiments were performed in triplicates and standard deviations were derived from the coefficient variations of experimental and control samples. P is derived from t-test analyses and N denotes the sample size.

We examined how Egfr cooperates with oncogenic Ras. Egfr could exert this tumour-promoting effect by regulating apoptosis and/or cell proliferation. We examined cell death in RasV12 or RasV12, Egfr_ double mutant clones using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end-labelling (TUNEL) assays. We did not detect ectopic cell death inside RasV12, Egfr_ double mutant clones compared with RasV12 clones (Fig. 1k–n). Instead, Egfr_ reduced the cell proliferation potential of RasV12 cells, as indicated by the decrease in the percentage of phospho-histone3 positive cells in RasV12, Egfr_ double mutant clones compared with RasV12 clones (Fig. 1o,q versus p,r; quantified in 1s). Thus, Egfr fosters oncogenic Ras-mediated tumour overgrowth by promoting cell proliferation.

RasV12 activates spitz to promote non-canonical Egfr signalling

Oncogenic Ras could recruit Egfr's function by upregulating Egfr or its ligands. Oncogenic activation of the MAPK pathway has been shown to trigger the overexpression of Egfr and autocrine activation of Egfr by transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-α) family of Egfr ligands in cancer cells4,6. Drosophila has two TGF-α homologs, Gurken (Grk) and spitz (Spi)30,31. The expression and function of Grk are restricted to the germline in embryos, while Spi is broadly expressed and potently activates Egfr throughout all stages of development30,32. While we did not detect any change in Egfr protein levels in RasV12 clones (Fig. 2a), an antibody against the extra cellular domain of Spi showed elevated spi protein levels in and around RasV12 clones (Fig. 2b and b'). This argues that RasV12 cells upregulate Spi. Consistent with this, quantitative polymerase chain reaction analyses revealed that RasV12 transcriptionally stimulates Spi (Fig. 2k). Next, we assessed the functional significance of Spi's upregulation on tumour overgrowth. We introduced a null Spi mutation (spi_) in RasV12 cells and scored clone sizes compared with RasV12 clones. Similar to Egfr_, the spi_ mutation produced small clones and suppressed the overgrowth phenotype of RasV12 (Fig. 2c,d; quantified in j, and Supplementary Fig. 1d,g,j,m). In addition, we examined the effect of knocking down Star, which is required for Spi secretion and its growth control function (Supplementary Fig. 1a,c, and ref. 33). This also suppressed RasV12-mediated tumour overgrowth (Fig. 2c,e). Moreover, we took advantage of a conditional ligand-binding-defective Egfr allele, Egfrtsla (ref. 34). We examined the effect of this mutation on RasV12 tumour overgrowth at restrictive conditions and found that it also suppressed overgrowth (Fig. 2c,f, and Supplementary Fig. 1d,g,k,n). Collectively, these data argue that oncogenic Ras stimulates spi, which in turn triggers Egfr to increase tumour growth.

Egfr could contribute to oncogenic Ras-mediated overgrowth by augmenting canonical Egfr signalling levels via Ras35. Alternatively, Egfr signalling could exert its growth promoting effect via a previously uncharacterized mechanism. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we first tested whether knocking down Sos has an effect on RasV12 tumour overgrowth. While the expression of Sos-RNAi caused a small eye phenotype in adult animals, consistent with Egfr/Ras signalling inhibition (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b,d,g,l and o), it showed no effect on oncogenic RasV12 tumour overgrowth (Fig. 2c versus g). Similarly, direct inactivation of wild-type Ras using a null allele (rasC40A) (ref. 36), produced small clones (Fig. 2h) but failed to suppress the RasV12 tumour overgrowth phenotype (Fig. 2c versus i). Taken together, the above data indicate that ligand-mediated Egfr function promotes oncogenic Ras tumour overgrowth independent of canonical Egfr signalling.

Egfr promotes RasV12 -mediated tumour overgrowth via ARF6

In an effort to further elucidate how Egfr promotes oncogenic Ras-driven tumour overgrowth, we knocked down Egfr effectors (Drk and Arf6) by RNAi and asked whether this suppress oncogenic Ras-mediated tumour overgrowth, and identified Arf6 as a mediator of Ras tumour overgrowth. Arf6 belongs to a family of highly conserved small Ras-related GTP-binding proteins and mediates Egfr signalling in mammals and flies15,37,38,39. Arf6 knockdown in otherwise wild-type clones showed no detectable growth defects (Figs 1a and 3b) but potently suppressed RasV12 tumour overgrowth (3a–c; quantified in 3e). In addition, Egfr directly recruits Arf6 GEFs to stimulate Arf6 (refs 37, 38). We examined the effect of knocking the known Arf6 GEFs steppke and loner38,40. Knockdown of loner, but not steppke, suppressed RasV12 tumour overgrowth (Fig. 3a,d–f, and Supplementary Fig. 1e,h), mimicking the effect of blocking the function of spi or Egfr or Arf6. In addition, we over-expressed Egfr in wing discs and asked whether knocking down Arf6 suppresses Egfr-mediated overgrowth effect and found that it does (Supplementary Fig. 2). Taken together, these data support the notion that Egfr acts through Arf6.

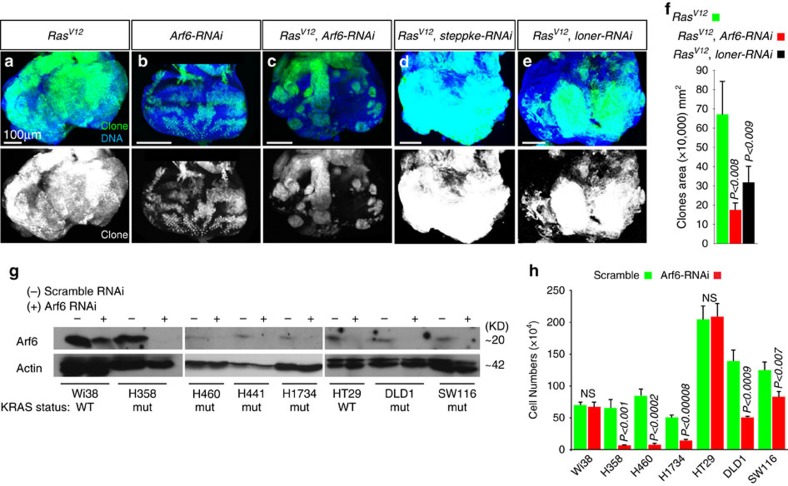

Figure 3. Arf6− suppresses oncogenic Ras tumours in flies and human cancer cells.

(a–e) Representative images of wondering third-instar larval eye discs showing the growth of RasV12 (a) or Arf6-RNAi (b) clones or RasV12 clones co-expressing either Arf6-RNAi (c) or steppke-RNAi (d) or loner-RNAi (e). All animals were raised at 25 °C. Arf6-RNAi (b) causes no detectable growth defects but suppresses RasV12 tumour overgrowth (c). loner-RNAi (e), but not steppke-RNAi (d), blocks the overgrowth of RasV12 clones (d). (f) Quantitation of (a–d). Clones areas were 17.3±3.4 × 104, N=128 clones, P<0.008 (RasV12 clones expressing Arf6-RNAi) or 31.7±8.1 × 104, N=110, P<0.009 (RasV12 clones expressing loner-RNAi) versus 67.1±16.8 × 104, N=20 clones (RasV12 clones). (g) Western blotting of various cancer cell lines treated with scramble or Arf6 RNAi and blotted with anti-Arf6 to detect Arf6 protein levels or anti-actin as a loading control. Cancer cells harbouring oncogenic Ras are denoted by mut while cells with wild-type Ras are indicated by WT. ARF6 protein levels are considerably reduced in cells treated with Arf6 RNAi. (h) Quantitation of cell numbers of lung and cancer cell lines 2 days after transfection with either control (scramble) or Arf6 RNAi. Not significant (NS) denotes P-value>0.5. P is derived from t-test analyses and N denotes the sample size.

Given our fly tumour data, we tested whether Arf6 serves as a molecular link in the cooperation between oncogenic Ras and Egfr in human cancer cells. We knocked down Arf6 in various lung and colon cancer cell lines with oncogenic Ras mutations. We found that Arf6-RNAi specifically reduced Arf6 protein levels and suppressed the growth of these cancer cells in comparison to cancer cells without oncogenic Ras mutations or cells treated with RNAi control (Fig. 3g,h, and Supplementary Fig. 3a). We conclude that in both Drosophila and human cells, Arf6 has a critical role in the growth of Ras mutant tumours.

Arf6 regulates Hh signalling to stimulate Ras tumour overgrowth

We sought to define the mechanism by which Arf6 drives the overgrowth of RasV12 tumours. Hh signalling is a good candidate because it cooperates with Egfr to drive basal cell carcinoma and melanomas via an unknown mechanism11,12. Consistent with the possibility that Hh signalling could be involved in Egfr/Arf6-mediated Ras tumour overgrowth, we found that Hh was upregulated and co-localized with Arf6 in RasV12 clones (Supplementary Fig. 4). We assessed the status of Hh signalling by examining the expression levels of its transcriptional target Cubitus interuptus (Ci or Gli in vertebrates) in complementing biochemical and immunostaining experiments. Using antibody against active Ci, we found that Ci protein levels were elevated in lysates derived from dissected RasV12 discs compared with controls (Fig. 4a). Next, we directly stained wild-type or RasV12 mosaic tissues against Ci. In wild-type discs ci is suppressed posteriorly while Hh activates ci anteriorly (Fig. 4g: bottom and top brackets, respectively)41. In contrast, ci was upregulated in posterior RasV12 clones and this upregulation was more pronounced in larger clones (see discussion) (Fig. 4b,c, and corresponding bottom panels). In addition, expression of RasV12 in wing discs, showed ectopic ci activation (Supplementary Fig. 5). We conclude that oncogenic Ras activates Hh signalling.

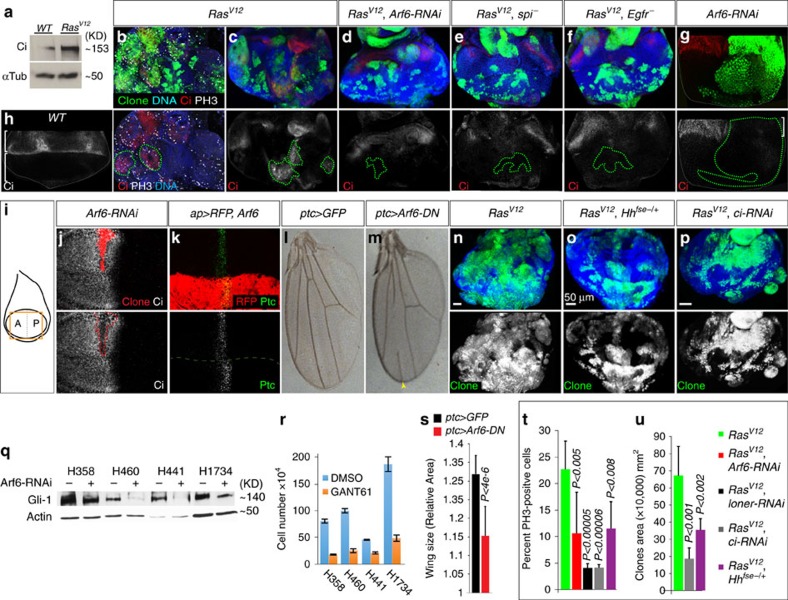

Figure 4. Arf6 regulates Hedgehog signalling to control tumour overgrowth.

a) Protein lysates derived from dissected wild-type discs or discs with RasV12 clones were used in western-blotting experiments to detect active (full-length) Ci protein levels against the loading control (α-tubulin). (b–f) Early 3rd-instar eye discs showing ey-FLP MARCM clones of the indicated genotype stained with DAPI, anti-Ci, and/or anti-PH3. Bottom panels show PH3 and/or Ci separately. In this and all the remaining panels, dotted lines denotes clones boundary. (g) Early 3rd-instar eye disc showing hs-FLP MARCM Arf6-RNAi clones stained with anti-Ci. The bottom panel shows the Ci channel. h) Wild-type eye disc stained against Ci. The top bracket denotes the zone of high Hh signalling in the eye. (i) Schematic of a wing disc. The box illustrates the region of the disc shown in (j and k). j) Early 3rd-instar wing disc showing hs-FLP Arf6-RNAi MARCM clones (red) and stained against Ci. The Ci channel is shown in the bottom panel. (k) Expression of Arf6-RNAi in the dorsal domain (RFP) of the wing pouch in early 3rd-instar animals using apterus-GAL4 and stained with anti-patched. Bottom panel shows patched channel alone. The dotted line delimits the dorsal-apterus domain in the wing pouch. (l and m) Ptc-GAL4 expression of GFP or Arf6-DN (n–p) Similarly-aged eye discs showing clone growth for cells expressing RasV12 alone (n) or with Hhfse-/+ (o) or ci-RNAi (p). Clone channels are shown in bottom panels. (q) Western blotting of various lung cancer cell lines treated with scramble or Arf6 RNAi and blotted with anti-Gli1 or anti-actin. (r) Lung cancer cell lines treated either with DMSO or GANT61. (s) Quantitation of relative wing sizes from o and p. (t) Quantitation of the percentage of PH3-positive cells in clones of the indicated genotypes. (Mean±SD%, N, P): 11.5±5%, N=1868, P<0.008 (RasV12, Hhfse-/+) or 10.6±7.7%, N=2301, P<0.005 (RasV12, Arf6-RNAi) or 4.1±0.7%, N=1764, P<0.00005 (RasV12, loner-RNAi) or 4.15±0.5 %, N=6738, P<0.00006 (RasV12, ci-RNAi) versus 27.7±5.2%, N=2100 for RasV12. u) Quantitation of (n-p). (Mean±SD%, N, P): 35.3±6.3x104 mm2, N=171 clones, P<0.002 (RasV12, Hhfse-/+) or 18.5±6.1x104 mm2, N=58 clones, P<0.001 (RasV12, ci-RNAi). P is derived from t-test analyses and N denotes the sample size.

The overexpression of ci in eye disc clones correlated with increased cell proliferation as determined by phospho-histone3 immunostaining (Fig. 4b and bottom panel). Knockdown of Arf6 suppressed Hh signalling in similar size clones and correspondingly reduced cell proliferation in RasV12 clones (Fig. 4b,c and t). Removing Spi or Egfr function in RasV12 clones (RasV12, spi_ or RasV12, Egfr_ double mutant cells) showed similar effects (Fig. 4b,c,e, and f), consistent with the notion that Egfr/Arf6 signalling stimulates Hh signalling in Ras tumours.

We have previously shown that tumours co-opt developmental mechanisms to promote overgrowth25. During development, dying cells upregulate Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signalling, which in turns instructs neighbouring cells to activate Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK-STAT) signalling and proliferate in order to maintain tissue homeostasis. RasV12 cells usurp this compensatory cell proliferation mechanism by forcing JNK activation in surrounding wild-type cells via elevated secretion of JNK signalling ligands, leading to tumour overgrowth25. We thus examined whether Arf6 regulates Hh signalling during normal development. In the developing eye imaginal disc, anterior cells activate Hh signalling in response to Hh secreted from the posterior cells (Fig. 4h and ref. 41). Similarly, the engrailed gene is specifically expressed in the posterior compartment (P) of the developing wing disc where it induces Hh expression but represses ci42. Posterior cells relay Hh to the anterior compartment (A) where Hh activates target genes including ci and patched (ptc) to control wing size and patterning43,44. We generated Arf6-RNAi clones in developing eye and wing discs, examined Hh signalling in the Hh responsive anterior cells, and found that Arf6-RNAi suppressed Hh signalling in both tissue types (Fig. 4g and bottom panel, bracket, and j; respectively). Conversely, we overexpressed Arf6 in wing discs using the dorsal driver apterus-GAL4 (ap-GAL4) and asked whether this upregulates Hh. Posteriorly produced Hh normally activates ptc in a 8–10 cells diameter domain along the A/P boundary. Consistent with enhanced Hh signalling, ap-Gal4>UAS-ARF6 discs showed elevated Ptc protein levels and an expansion of the Ptc domain specifically in the apterus-dorsal portion of the disc (Fig. 4k).

Next, we directly knocked down Arf6 along the A/P compartments boundary where high levels of Hh signalling regulate the patterning and growth of the wing. Arf6 knockdown interfered with the formation of the anterior cross vein and that of the longitudinal vein 3 (L3), a processes regulated by Hh signalling45 (Fig. 4l,m, and arrowhead). Importantly, Arf6 knockdown significantly reduced wing size compared with controls (ptc-GAL4>GFP) (Fig. 4l,m,s, and Supplementary Fig. 6). Taken together, these data indicate that Arf6 regulates Hh signalling in Ras tumours and during development.

We subsequently tested whether Egfr/Arf6-triggered Hh signalling synergizes with oncogenic Ras to cause tumour overgrowth. We analysed the growth of RasV12 clones induced in tissues heterozygotes for a hypomorphic allele of Hh, Hhfse (ref. 46), thus reducing Hh function by less than 50% compared with controls. We found that this considerably blocked cell proliferation and the overgrowth phenotype of RasV12 clones (Fig. 4n,o; quantified in t and u). RNAi knockdown of ci showed a similar effect (Fig. 4n,p; quantified in t and u). Egfr/Arf6-triggered Hh signalling thus synergizes with oncogenic Ras to cause tumour overgrowth.

Finally, we determined whether Arf6 similarly regulates Hh signalling in human cancer lines by examining changes in Gli1 expression levels following Arf6 RNAi knockdown. We focused on lung cancer cell lines because Arf6 knockdown potently inhibited growth in these cancer cells. Arf6 RNAi efficiently knocked down Arf6 protein levels (Fig. 3g) and reduced Gli1 levels in lung cancer cells (Fig. 4q and Supplementary Fig. 9). Direct inhibition of Hh signalling using GANT61, a specific Gli1 small molecule inhibitor47,48, suppressed growth similar to Arf6 knockdown (Fig. 4r). Taken together, we conclude that Arf6 regulates Hh signalling in both flies and human cancer cells to control growth.

Arf6 controls Hh trafficking

We investigated the relationship between EGFR, ARF6 and Hh using immunostaining and immunoprecipitation experiments. We previously observed that Arf6 co-localizes with Hh in RasV12 cells (Supplementary Fig. 4) and thus wondered whether Egfr modulates RasV12 tumour overgrowth by regulating an interaction between Arf6 and Hh. We performed Arf6 pull-down experiments in the presence or absence of Egfr and found that abrogating Egfr function in RasV12 cells diminishes Arf6's ability to pull-down Hh (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 7a), indicating that Egfr promotes the interaction of Arf6 with Hh. We then explored a mechanism for Arf6 regulation of Hh. Endocytosis and vesicle transport are known to control Hh signalling13. We hypothesized that Arf6 could promote the shuttling of Hh to signalling competent endosomes. In the absence of Arf6, Hh would be routed to the degradation pathway hence causing suppression of Hh signalling. The Hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (Hrs) binds to and directs signalling molecules to the lysosomal degradation pathway to downregulate signalling49. We examined Hh localization to Hrs-positive vesicles and found that Arf6 knockdown caused Hh to predominantly localize to Hrs-positive vesicles compared with controls (Fig. 5b,e and f). Knocking down Egfr in RasV12 cells showed similar effects (Supplementary Fig. 7b–d). In addition, we directly used late endosomal markers (Arl8 and Rab7) to test whether Arf6 knockdown causes trafficking of Hh to lysosomal vesicles. We could not co-stain tissues with anti-Hh and anti-Arl8 (or anti-Rab7) antibodies because these antibodies were raised in the same species. Instead we used the GMR-GAL4 driver to express GFP-labelled full-length or a version of Hh corresponding to its secreted and active form (Hh-GFP and Hh-N-GFP, respectively) in cells expressing either RasV12 alone or co-expressing Arf6-DN or Arf6-RNAi, and stained tissues against Arl8. We found that Hh-GFP preferentially localizes to clusters of Arl8-positive vesicles in RasV12, Arf6-DN tissues (Fig. 5c,c' and g). Similarly, we expressed Rab7-GFP in RasV12, Arf6-DN cells, stained against Hh, and found that Hh predominantly localizes to Rab7-GFP vesicles in these cells compared with controls (RasV12 cells) (Fig. 5d,h versus i,m). Moreover, expression of Arf6-RNAi in RasV12 cells resulted in the redistribution of Hh-N-GFP to Arl8 endosomes (Fig. 5j,n versus k,o). Furthermore, expression of Arf6-RNAi in otherwise wild-type cells similarly showed Hh localization to Rab7 endosomes (Supplementary Fig. 7e,f and h). Consistent with this, Patched (Hh receptor) localizes to Rab7 or Arl8 endosomes in Arf6-RNAi or Arf6-DN expressing cells (Fig. 5l,p, and Supplementary Fig. 6g–j). Together with the Hh-Hrs colocalization results above, these data indicate that Arf6 normally prevents the trafficking of Hh to the degradation pathway. Thus, Arf6 controls Hh trafficking in order to promote Hh signalling, which in turn cooperates with RasV12 to synergistically stimulate tumour overgrowth.

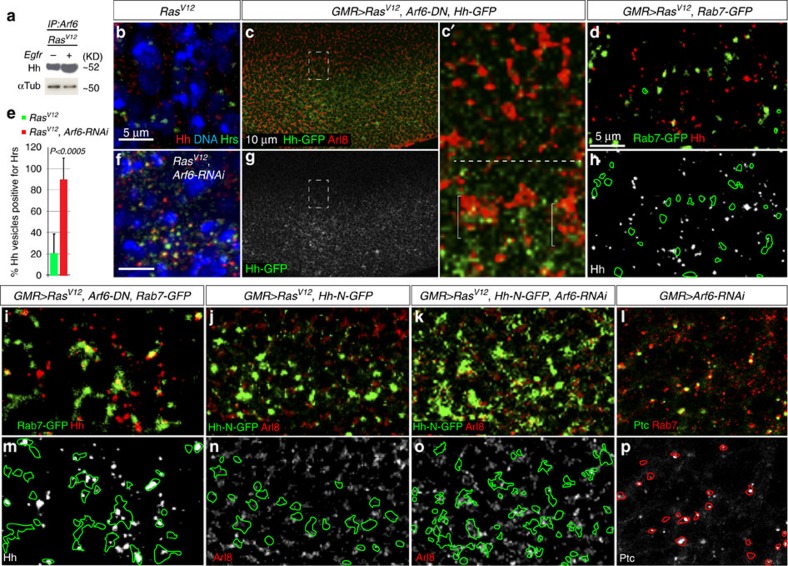

Figure 5. Arf6 controls Hedgehog cellular trafficking.

(a) Protein lysates derived from dissected wild-type discs or discs with RasV12 tumours were used in western-blotting experiments to detect full-length (active) Cubitus interuptus (Ci) protein levels against the loading control (α-tubulin). Hh co-precipitates with Arf6 but the Egfr− mutation interferes with Arf6's ability to interact with Hh. (b,f) RasV12 or RasV12, Arf6-RNAi co-expressing cells stained with anti-hedgehog, anti-Hrs antibodies and DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Distinct Hh (red) or Hrs (green)-positive vesicles are detected in RasV12 cells (b). In contrast, Hh predominantly localizes to Hrs-positive vesicles in RasV12, ARF6-RNAi co-expressing cells (f). (c) Eye disc co-expressing Hh-GFP, RasV12 and Arf6-DN under the control of GMR-GAL4 and stained against Arl8. The Hh-GFP channel alone is shown in g. Higher magnification image of posterior/anterior boundary (boxed area) is shown in c'. Hh-GFP localizes to clusters of Arl8-positive vesicles specifically in the posterior portion of the eye disc (brackets), but not in the anterior region of the eye (above the dotted line). (d,h,l,m) Images from eye disc co-expressing either RasV12 and Rab7-GFP (d,h) or RasV12, Arf6-DN, and Rab7-GFP (i,m) using GMR-GAL4 and stained with anti-Hh antibodies. Images of the Hh channel for d,i are shown in h,m, respectively. Fluorescent signal contours of Rab7-GFP (m) and Hh-N-GFP (n,o) are shown in m–o. (e) Quantitation of Hh punctae localizing to Hrs-positive vesicles. The total number of Hh punctae in RasV12 or RasV12, Arf6-RNAi co-expressing cells (N=27 and 32, respectively) was scored for each genotype and the respective percentage of Hh localizing to Hrs-positive vesicles was determined. (j,k) Images from an eye disc co-expressing RasV12 and the secreted form of Hh (Hh-N-GFP) alone (j) or in the presence of Arf6-RNAi (k) and stained with anti-Arl8 antibodies. The respective Arl8 images are shown in the bottom panels n,o. (l) Image from an eye disc expressing Arf6-RNAi with GMR-GAL4 and stained against patched (ptc) and Rab7. The corresponding patched channel is shown alone in p. Rab7 fluorescent signal contours are shown in p. P is derived from t-test analyses and N denotes the sample size.

Discussion

How oncogenic Ras signalling elicits Egfr and Hh functions and how these distinct signalling events are integrated to achieve oncogenic synergy in cancers is not well understood. Using a Drosophila tumour model we found that oncogenic Ras transcriptionally stimulates the TGF-α Egfr ligand spitz to recruit Egfr signalling and increase tumour growth. Egfr's role is likely tissue and/or context-dependent as inhibition of Egfr shows variable effects in different cancer types4,5,50. Interestingly, Egfr inhibition in RasV12 appeared to cause a non-autonomous growth effect (Fig. 1a,d and e), suggesting that JNK signalling is involved51. However, blocking JNK signalling fails to rescue the growth of RasV12, Egfr− clones (Supplementary Fig. 8). Thus Egfr− suppresses RasV12 tumour overgrowth independent of JNK signalling. Instead, further analyses unexpectedly uncovered a non-canonical signalling modality for Egfr in RasV12 cells. Rather than signalling via the MAPK pathway, Egfr acts through Arf6. Knockdown of Arf6 in flies or human cancer cells suppresses the overgrowth of cell harbouring oncogenic Ras. This effect is due to a cell proliferation defect because, similar to Egfr knockdown, Arf6 knockdown showed no ectopic cell death in cancer lines with the highest growth suppression effect (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

We show that Arf6 acts via Hh signalling. Egfr promotes Arf6 to interact with Hh in order to stimulate Hh signalling. Arf6 stimulates Hh signalling by protecting Hh from lysosomal degradation. Consistent with this, Arf6 regulates the formation of carrier vesicles and interacts with lysosomes to control vesicle trafficking in epithelial cells52,53. We show that disrupting the interaction between Arf6 and Hh by either blocking Egfr or by directly depleting Arf6 causes Hh to accumulate in lysosomal vesicles. Interestingly, Arf6-depleted cells also show an increased number of Hrs-positive endosome overall, suggesting that Arf6 may impact other unknown signalling molecules in addition to Hh.

Hh signalling is activated in Ras tumour cells, and it is especially higher in larger clones. This could be because bigger clones produce more Spi and Hh in the clones' milieu allowing Arf6 to drive Hh signalling robustly in these cells. Importantly, blocking Egfr or Arf6 suppresses Hh signalling and correspondingly inhibits overgrowth in both flies and human cancer cells. Direct inhibition of Hh signalling suppresses the growth of fly and human cancer cells. Indeed we found that the overgrowth of Ras tumours is hypersensitive to Hh signalling dosage. Partial reduction of Hh protein is sufficient to effectively block tumour overgrowth, consistent with a synergetic cooperation. Thus Egfr/Arf6 has an important role in bridging oncogenic Ras and Hh signalling pathways.

Finally, we found that Arf6 regulates Hh signalling during normal development. ARF6 knockdown inhibited Hh signalling in developing imaginal discs and impinged on Hh signalling-regulated developmental processes.

Together our data highlight a non-canonical Egfr signalling mechanism centered on a novel role for Arf6 in Hh signalling regulation. We define a novel signalling mechanism that explains the perplexing requirement of Egfr in oncogenic Ras-mediated overgrowth and the oncogenic cooperation between Egfr and Hh signalling.

Methods

Experimental procedures

Fly lines. Animals were aged at 25 °C on standard medium. The following fly lines were used in this study: (1) y w; FRT82B; (2) y w; FRT82B, UAS-RasV12/TM6B; (3) EgfrTop−CA (T. Schupback, Princeton Univ.); (4) UAS-DER(DN) (A. Michelson, Harvard Univ.); (5) UAS-spi-RNAi (VDRC # 3922); (6) cn1 Egfrtsla bw1/T(2;3)TSTL, CyO: TM6B, Tb1(BDSC# 6501);(7) FRT40, rasc40A (C. Berg, Univ. of Washington);UAS-ARF6-RNAi (VDRC # 24224, 100726; BDSC# 51417, 27261); (8) UAS-loner-RNAi (VDRC #106168 and BDSC#39060); (9) UAS-ci-RNAi (BDSC# 28984); (10) spi, FRT40A/CyO (BDSC#114338); (11) yw,ey-Flp1;act>y+>GAL4,UAS-GFP.S65T;FRT82B,tub-GAL80; (12) Hhfse (BDSC# 35562); (13)yw,ey-Flp1;act>y+>GAL4,UAS-myrRFP;FRT82B,tub-GAL80; (14) yw,ey-Flp1; FRT42D,tub-GAL80; act>y+>GAL4,UAS-GFP; (15) UAS-ARF6-DN (E. Chen, Johns Hopkins Univ.); (16)yw,ey-Flp1;tub-GAL80,FRT40A;act>y+>GAL4,UAS-GFP.S65T; (17) Star-RNAi (BDSC# 38914); (18) Sos-RNAi (BDSC#31174); (19) Arf6-GFP line is a previously generated and functionally validated GFP knock-in line54,55 kindly provided by Y. Hong (University of Pittsburg). In brief, the Arf6 gene is under endogenous control and a GFP is inserted in frame at the carboxyl terminus of Arf6 protein; (20) UAS-steppke-RNAi (BDSC#32374); (21) UAS-Hh-GFP and UAS-Hh-N-GFP, a gift from A. O'Reilly (Fox Chase Cancer Center, PA); (22) yw, hsp70-Flp; act-y+-GAL4, UAS-GFP. See Supplementary Note 1 for genotype details of all images.

Clones. Clones were generated using standard MARCM techniques56. Detailed genotypes for all images are included in Supplementary Information. Briefly, all clones were induced with ey-FLP MARCM system, to the exception of Fig. 4g,j, which were generated with hs-Flp. For these particular experiments, 2 days larvae were heat-shocked for 1 h at 37 °C and raised for two days at 25 °C before processing. Images presented in Figs 2f, 4l,m, and Supplementary Figs 1k,n, 2, 5 and 6 were obtained from animal raised at 29 °C. For all remaining images, animals were raised at 25 °C. Clone size was obtained by determining the average clone area in discs dissected from randomly selected wondering third-instar control versus experimental larvae using the image analysis IMARIS. Properly aged GFP-positive mosaic animals were randomly and blindly selected under a dissecting microscope using white light to eliminate bias. Minimum sample sizes were determined using a 5% confidence level and 80% power. The minimum sample sizes were then used to estimate the number of animals/discs to be examined.

Staining and imaging

Eye-antenna discs were dissected, fixed and stained as described previously25,26. Tumour and adult eyes sizes analyses were carried out on a Leica MZ FLIII fluorescence stereomicroscope equipped with a camera. Samples were examined by confocal microscopy with a Zeiss LSM510 Meta system and a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope. Images were analysed and processed with IMARIS (Bitplane, Switzerland) and Illustrator (Adobe) software, respectively. The following primary antibodies were used: guinea pig anti-Hrs (1:2,000, H. Bellen); Mouse anti-Spi (1:500; A.D. Vrailas-Mortimer); Rabbit anti-phosphohistone-H3 (1:1,000, Sigma); Rat anti-DER (1:1,000, B. Shilo, Weizmann Institute of Science/Israel); Mouse anti-EGFR (1:500, abcam); Rabbit anti-GFP (1:1,000, Abcam); Rabbit anti-Hh (1:500 Pre-absorbed, T. Kornberg, UCSF); Rat anti-Ci (detects the full length/active version of Ci, 1:200, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, 2A1); Mouse anti-Patched (1:200, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Apa1). Secondary antibodies were from Invitrogen. TUNEL staining was performed using the Apoptag Red kit from Chemicon.

Western blots and immunoprecipitation

For immunoprecipitation experiments, imaginal discs from 50 third-instar animals carrying RasV12 single or EgfrTop−CA, RasV12 or DerDN(EGFR-DN), RasV12 double mutant clones were homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.01% Triton-X) supplemented with protease inhibitor tablets; Roche). Global protein concentrations was normalized across all genotypes and the lysate was pre-cleared with protein agarose-A beads for 1 h at 4 °C, incubated either with 2 μl of anti-Arf6 (M. Gonzalez-Gaitan) for 4 h at 4 °C. Lysates were then incubated with protein agarose A beads for 1 h at room temperature. For pull downs, beads were precipitated and washed three times in modified lysis buffer containing 0.5% TritonX-100. Samples were run on SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred on nitrocellulose membrane, and blotted with anti-Hh (T. Kornberg, UCSF) and anti-αTubulin (Sigma), loading control. For cancer cell lines, cells were lysed in lysis-loading buffer (0.5 M Tris (pH 6.8), 20% SDS, Glycerol, 10% β-mercaptoethanol and Bromophenol Blue), homogenized further by hydrodynamic shearing (15 times through a 25-gauge syringe, and centrifuged at 10,000 r.p.m. for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and run on SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred on nitrocellulose membrane, and blotted with anti-Gli1 (1/1,000; Abcam, cat# ab134906) or anti-Arf6 (1/1,000; Abcam, Cat# ab77581) or anti β-actin (1/1,000; Sigma, cat# A5441) antibodies. Full images of the blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 9.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA from Eye-antenna imaginal discs containing wild-type or mutant clones was isolated using a Trizol RNA extraction method (Invitrogen). The SuperScriptIII First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) kit was used to synthesize complementary DNA. Real-time PCR was carried out on an Applied Biosystems machine using the SYBR green fast kit (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer's instructions. Relative gene expression was obtained from triplicate runs normalized to Rp49 as endogenous control. The following primers were used: Rp49, 5′-GGCCCAAGATCGTGAAGAAG-3′ and 5′-ATTTGTGCGACAGCTTAGCATATC-3′; Spitz, 5′-CGCCCAAGAATGAAAGAGAG-3′ and 5′-AGGTATGCTGCTGGTGGAAC-3′

Clones of mutant cells in the eye-antennal discs were generated using standard MARCM system56. Immunostaining and Immunoprecipitation experiments were performed as previously described57.

ARF6 RNAi gene knockdown in human cancer cell lines

In all, 2 × 105 cells were seeded onto 6-well-plates and treated with 2 nM of either ARF6 SiRNA (combination of three SiRNA of ARF6, Origene; Cat# SR300275) or universal control scrambled (Origene, SiRNA Cat# SR30004) and supplemented with 5 μl of DhamaFect 2 (GE- Dharmacon).

Treatment of lung cancer cells with GANT61

Cells were seeded onto 6-well-plates at a density of 2 × 105 and grown overnight before GANT61 (Cat# G9048-5MG, Sigma-Aldrich) treatment at the final concentration of 10 μm ml−1. Cell numbers were scored 96 h after GANT61 treatment.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Chabu, C. et al. EGFR/ARF6 regulation of Hh signalling stimulates oncogenic Ras tumour overgrowth. Nat. Commun. 8, 14688 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14688 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures and Supplementary Note.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Schupback (Princeton Univ. NJ), A. Michelson (Harvard Univ. MA), C. Berg (Univ. of Washington, WA), E. Chen (Johns Hopkins Univ. MD), Bloomington stock center, and the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center for kindly providing reagents. This study was supported in part by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (MOST2013CB945301) and from NIH/NCI to T.X. C.C. is funded by an NIH/NCI post-doctoral grant (1F32CA142118-01A1). T.X. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions C.C. and T.X. designed the research. C.C. performed experiments and analysed the data. D.-M.L. performed the mouse and human Arf6 RNAi knockdown experiments. C.C. and T.X. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Bos J. L. ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 49, 4682–4689 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 11–22 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardeesy N. et al. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in RAS-driven melanoma. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 4176–4188 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardito C. M. et al. EGF receptor is required for KRAS-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 22, 304–317 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navas C. et al. EGF receptor signaling is essential for k-ras oncogene-driven pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 22, 318–330 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou G. Y. et al. Mutant KRas-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress in acinar cells upregulates EGFR signaling to drive formation of pancreatic precancerous lesions. Cell Rep. 14, 2325–2336 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casci T. & Freeman M. Control of EGF receptor signalling: lessons from fruitflies. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 18, 181–201 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick F. Signal transduction. How receptors turn Ras on. Nature 363, 15–16 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimeault M. & Batra S. K. Frequent deregulations in the hedgehog signaling network and cross-talks with the epidermal growth factor receptor pathway involved in cancer progression and targeted therapies. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 497–524 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecca B. et al. Melanomas require HEDGEHOG-GLI signaling regulated by interactions between GLI1 and the RAS-MEK/AKT pathways. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 5895–5900 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl M. et al. Hedgehog-EGFR cooperation response genes determine the oncogenic phenotype of basal cell carcinoma and tumour-initiating pancreatic cancer cells. EMBO Mol. Med. 4, 218–233 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Z., Mei F. C., Xie J. & Cheng X. Oncogenic KRAS activates hedgehog signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14048–14055 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallet A. & Therond P. P. Temporal modulation of the Hedgehog morphogen gradient by a patched-dependent targeting to lysosomal compartment. Dev. Biol. 277, 51–62 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter I. R. & Wittinghofer A. The guanine nucleotide-binding switch in three dimensions. Science 294, 1299–1304 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson J. G. Multiple roles for Arf6: sorting, structuring, and signaling at the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41573–41576 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozza G. et al. Role of ARF6, Rab11 and external Hsp90 in the trafficking and recycling of recombinant-soluble Neisseria meningitidis adhesin A (rNadA) in human epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 9, e110047 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza-Schorey C., Li G., Colombo M. I. & Stahl P. D. A regulatory role for ARF6 in receptor-mediated endocytosis. Science 267, 1175–1178 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence J. T. & Birnbaum M. J. ADP-ribosylation factor 6 delineates separate pathways used by endothelin 1 and insulin for stimulating glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 5276–5285 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigent M. et al. ARF6 controls post-endocytic recycling through its downstream exocyst complex effector. J. Cell Biol. 163, 1111–1121 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shteyn E., Pigati L. & Folsch H. Arf6 regulates AP-1B-dependent sorting in polarized epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 194, 873–887 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale N., Chasserot-Golaz S. & Bader M. F. Regulated secretion in chromaffin cells: an essential role for ARF6-regulated phospholipase D in the late stages of exocytosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 971, 193–200 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. Z. & Mueckler M. ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6) defines two insulin-regulated secretory pathways in adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 25297–25300 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim F. D. & Rubin G. M. Ectopic expression of activated Ras1 induces hyperplastic growth and increased cell death in Drosophila imaginal tissues. Development 125, 1–9 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfar K., Rommel C., Stocker H. & Hafen E. Ras controls growth, survival and differentiation in the Drosophila eye by different thresholds of MAP kinase activity. Development 128, 1687–1696 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabu C. & Xu T. Oncogenic Ras stimulates Eiger/TNF exocytosis to promote growth. Development 141, 4729–4739 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarini R. A. & Xu T. A genetic screen in Drosophila for metastatic behavior. Science 302, 1227–1231 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford R. J. & Schupbach T. Coordinately and differentially mutable activities of torpedo, the Drosophila melanogaster homolog of the vertebrate EGF receptor gene. Genetics 123, 771–787 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker N. E. Cell proliferation, survival, and death in the Drosophila eye. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 499–507 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Hamlet M. R. & Perkins L. A. Analysis of corkscrew signaling in the Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor pathway during myogenesis. Genetics 159, 1073–1087 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge B. J., Zhang K., Bier E., Jan Y. N. & Perrimon N. The Drosophila spitz gene encodes a putative EGF-like growth factor involved in dorsal-ventral axis formation and neurogenesis. Genes Dev. 6, 1503–1517 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman-Silberberg F. S. & Schupbach T. The Drosophila dorsoventral patterning gene gurken produces a dorsally localized RNA and encodes a TGF alpha-like protein. Cell 75, 165–174 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R., Shaharabany M., Seger R. & Shilo B. Z. Secreted Spitz triggers the DER signaling pathway and is a limiting component in embryonic ventral ectoderm determination. Genes Dev. 9, 1518–1529 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsruya R. et al. Intracellular trafficking by Star regulates cleavage of the Drosophila EGF receptor ligand Spitz. Genes Dev. 16, 222–234 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A. B., Werner E. & Moses K. Genetic and biochemical analysis of the role of Egfr in the morphogenetic furrow of the developing Drosophila eye. Development 132, 4697–4707 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley C. et al. A requirement for wild-type Ras isoforms in mutant KRas-driven signalling and transformation. Biochem. J. 452, 313–320 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James K. E., Dorman J. B. & Berg C. A. Mosaic analyses reveal the function of Drosophila Ras in embryonic dorsoventral patterning and dorsal follicle cell morphogenesis. Development 129, 2209–2222 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R. et al. Arf6 regulates EGF-induced internalization of E-cadherin in breast cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 15, 11 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn I. et al. The Drosophila Arf GEF Steppke controls MAPK activation in EGFR signaling. J Cell Sci. 126, 2470–2479 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesin V., Montagnac G. & Chavrier P. ARF6 promotes the formation of Rac1 and WAVE-dependent ventral F-actin rosettes in breast cancer cells in response to epidermal growth factor. PLoS ONE 10, e0121747 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onel S., Bolke L. & Klambt C. The Drosophila ARF6-GEF Schizo controls commissure formation by regulating Slit. Development 131, 2587–2594 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt D. I. & Mlodzik M. Hedgehog is an indirect regulator of morphogenetic furrow progression in the Drosophila eye disc. Development 124, 3233–3240 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata T., Eaton S. & Kornberg T. B. The Drosophila hedgehog gene is expressed specifically in posterior compartment cells and is a target of engrailed regulation. Genes Dev. 6, 2635–2645 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aza-Blanc P. & Kornberg T. B. Ci: a complex transducer of the hedgehog signal. Trends Genet.: TIG 15, 458–462 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callejo A. et al. Dispatched mediates Hedgehog basolateral release to form the long-range morphogenetic gradient in the Drosophila wing disk epithelium. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 12591–12598 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullor J. L., Calleja M., Capdevila J. & Guerrero I. Hedgehog activity, independent of decapentaplegic, participates in wing disc patterning. Development 124, 1227–1237 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E. M. et al. Pointed regulates an eye-specific transcriptional enhancer in the Drosophila hedgehog gene, which is required for the movement of the morphogenetic furrow. Development 132, 4833–4843 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauth M., Bergstrom A., Shimokawa T. & Toftgard R. Inhibition of GLI-mediated transcription and tumor cell growth by small-molecule antagonists. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 8455–8460 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agyeman A., Jha B. K., Mazumdar T. & Houghton J. A. Mode and specificity of binding of the small molecule GANT61 to GLI determines inhibition of GLI-DNA binding. Oncotarget 5, 4492–4503 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jekely G. & Rorth P. Hrs mediates downregulation of multiple signalling receptors in Drosophila. EMBO Rep. 4, 1163–1168 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. J. et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 1960–1966 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo H. D., Gorenc T. & Steller H. Apoptotic cells can induce compensatory cell proliferation through the JNK and the Wingless signaling pathways. Dev. Cell 7, 491–501 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters P. J. et al. Characterization of coated vesicles that participate in endocytic recycling. Traffic 2, 885–895 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maranda B. et al. Intra-endosomal pH-sensitive recruitment of the Arf-nucleotide exchange factor ARNO and Arf6 from cytoplasm to proximal tubule endosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18540–18550 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Zhou W., Dong W. & Hong Y. Targeted engineering of the Drosophila genome. Fly (Austin) 3, 274–277 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Zhou W., Dong W., Watson A. M. & Hong Y. From the Cover: Directed, efficient, and versatile modifications of the Drosophila genome by genomic engineering. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 8284–8289 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T. & Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) for Drosophila neural development. Trends Neurosci. 24, 251–254 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabu C. & Doe C. Q. Dap160/intersectin binds and activates aPKC to regulate cell polarity and cell cycle progression. Development 135, 2739–2746 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures and Supplementary Note.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.