Abstract

Haematopoiesis is an essential process in early vertebrate development that occurs in different distinct spatial locations in the embryo that shift over time. These different sites have distinct functions: in some anatomical locations specific hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) are generated de novo. In others, HSPCs expand. HSPCs differentiate and renew in other locations, ensuring homeostatic maintenance. These niches primarily control haematopoiesis through a combination of cell-to-cell signalling and cytokine secretion that elicit unique biological effects in progenitors. To understand the molecular signals generated by these niches, we report the generation of caudal hematopoietic embryonic stromal tissue (CHEST) cells from 72-hours post fertilization (hpf) caudal hematopoietic tissue (CHT), the site of embryonic HSPC expansion in fish. CHEST cells are a primary cell line with perivascular endothelial properties that expand hematopoietic cells in vitro. Morphological and transcript analysis of these cultures indicates lymphoid, myeloid, and erythroid differentiation, indicating that CHEST cells are a useful tool for identifying molecular signals critical for HSPC proliferation and differentiation in the zebrafish. These findings permit comparison with other temporally and spatially distinct haematopoietic-supportive zebrafish niches, as well as with mammalian haematopoietic-supportive cells to further the understanding of the evolution of the vertebrate hematopoietic system.

Haematopoiesis is an essential process for all vertebrate organisms and is dependent on the generation, homeostasis, and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). HSCs are tissue-restricted stem cells with the ability to both self-renew and generate lineage-restricted hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs)1,2,3,4 that eventually differentiate into the multitude of mature blood cells that carry oxygen to distant tissues, prevent blood loss, and fight life-threatening infections. One of the ways that hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) become developmentally restricted is by receiving instructive signals from their microenvironment. As the developing vertebrate organism has multiple different sites of HSPC emergence, proliferation, and maintenance, understanding the signals produced by these niches is essential5,6,7. Elucidating and modulating the molecular pathways responsible for signalling between the niche and HSPCs that affect proliferation and/or differentiation is critical, because perturbations in blood development and homeostasis directly affect an organisms’ survival.

An increasingly popular model system for studying vertebrate haematopoiesis is zebrafish (Danio rerio)8. Zebrafish embryos develop externally and are optically transparent. Many hematopoietic lineage-specific transgenic lines exist, allowing the visualization of blood development in real time. Zebrafish are extremely fecund, allowing large scale, whole embryo genetic and small molecule screens for genes and pathways involved in hematopoietic development and disease. Importantly, zebrafish have a strong degree of evolutionary conservation with mammalian hematopoietic development and homeostasis; they have similar mature blood cells9, contain bona fide HSPCs10,11,12, and have similar genetic control of essential hematopoietic functions13. Importantly, drugs discovered in zebrafish show promise for treating human blood disorders14.

Zebrafish, like mammals, have shifting sites of haematopoiesis in the developing embryo; HSPCs are generated and expanded temporally in different anatomical regions (for a review, see refs 8,15). To investigate the signals produced by these different hematopoietic sites, we previously generated zebrafish embryonic stromal trunk (ZEST) cells16 derived from the site of HSC emergence17, which appear to be functionally equivalent to the mammalian aorta-gonad mesonephros (AGM) region. Interestingly, ZEST cells had similar signalling properties to another stromal cell line generated from the kidney18, the adult site of haematopoiesis in teleosts that is functionally equivalent to mammalian bone marrow (BM)19 in terms of supporting blood haemostasis. While HSCs are generated in the mammalian AGM20,21 and maintained in the BM22, they are transiently expanded in the embryo in the foetal liver (FL)23,24, which is equivalent to a vascularized region in the developing zebrafish tail referred to as caudal hematopoietic tissue (CHT)25. To characterize signalling from this location, we generated a primary stromal line termed caudal hematopoietic embryonic stromal tissue (CHEST) cells. These cells express hematopoietic-supportive cytokines and have endothelial properties. Importantly, CHEST cells also supported HSPC proliferation and differentiation when adult whole kidney marrow (WKM) was plated on them. Examining the signalling properties of these CHEST cells and comparing them to hematopoietic-supportive zebrafish kidney stroma (ZKS) and ZEST cells should illuminate conserved signalling pathways important for hematopoietic support and maintenance. It will also allow the investigation of specific signalling pathways that differ amongst these cells that make these temporally and spatially distinct locations unique. Finally, it will permit comparison of hematopoietic signals in the zebrafish to mammals; these evolutionarily conserved pathways are likely excellent targets to expand blood, generate HSCs, and drive specific lineage differentiation in vitro, all of which are important goals for regenerative medicine.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish stocks and embryos

Zebrafish were mated, staged, raised, and maintained in accordance with California State University, Chico (CSU Chico) and University of California, San Diego (UCSD) IACUC guidelines. All experiments were approved by the CSU Chico and UCSD IACUC before being performed. AB wild-type (wt) fish were utilized for these studies.

Generation of CHEST cells

CHEST cells were isolated by surgically removing the CHT from the trunk of 72-hour post fertilization (hpf) AB wild type (wt) fish. At 72 hpf, approximately 200 embryos were rinsed three times in sterile embryo medium26 in 10 cm2 plates. Using an Olympus SZ51 dissecting microscope, the tissue posterior to the yolk tube extension was removed with a sterile scalpel (see Fig. 1A; hatched area denotes the region that was isolated) and finely minced with a surgical scalpel and grown in zebrafish tissue culture medium16,18 with 5 ng/ml human fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) and 5 ng/ml sodium selenite added in a 12.5 cm2 tissue culture flask. The cells that attached to the surface of the flask were grown at 32 °C in 5% CO2 until cells achieved ≥ 80% confluence. Cells were trypsinized for 5 minutes and expanded onto 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks.

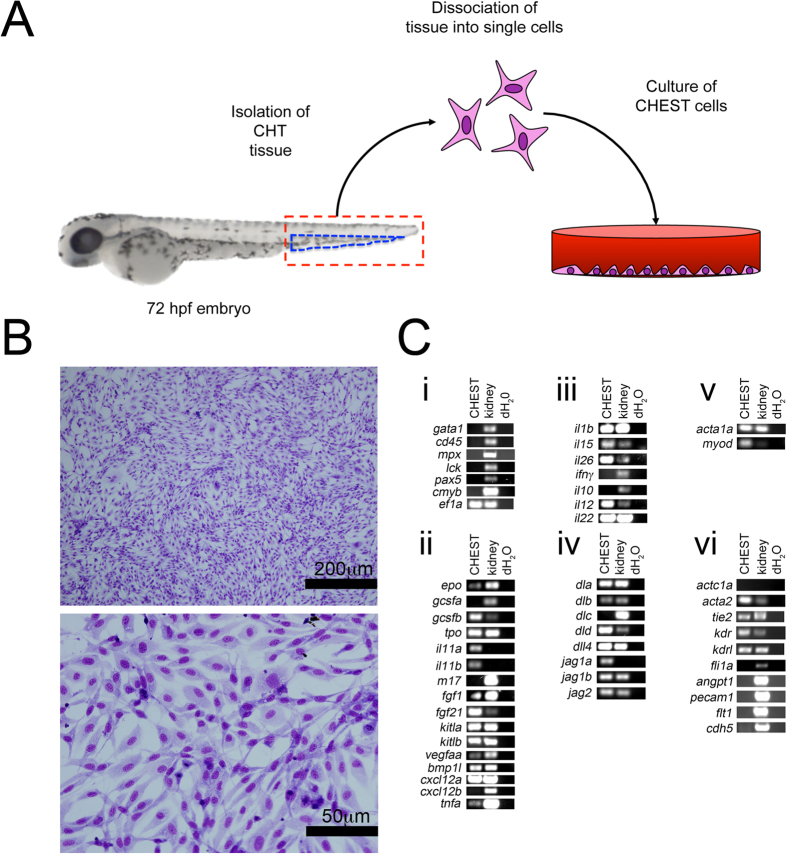

Figure 1. CHEST cells are a primary endothelial-like stromal cell line derived from the CHT of 72hpf zebrafish.

(A) Isolation and culture strategy for CHEST cells. Red hatched lines indicate the tissue removed for deriving CHEST cells, and the blue hatched lines indicate the anatomical location of the CHT region. (B) Monolayers of CHEST cells stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa. Top image: 400x, scale bar is 200 μm; bottom image: 1000x, scale bar is 50 μm. (C) RT-PCR analysis of (i) hematopoietic, (ii) hematopoietic-supportive cytokines, (iii) inflammatory signals, (iv) Notch pathway mediators, (v) skeletal muscle, and (vi) cardiac and endothelial transcripts. Gel images have been cropped for clarity of presentation.

Morphological characterization of CHEST cells

CHEST cells were grown on glass coverslips in culture media in 24-well tissue culture plates. When cells reached 100% confluence, they were fixed and stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa and visualized by microscopy27.

Proliferation of CHEST cells

CHEST cells were grown in 75 cm2 tissue culture flasks and treated with 1) ZKS/ZEST culture media16,18 alone, 2) ZKS/ZEST culture media with 5 ng/ml FGF2 added, 3) ZKS/ZEST culture media with 5 ng/ml sodium selenite added, or 4) ZKS/ZEST culture media with both FGF2 and sodium selenite. At various time points cells were isolated by trypsinization and enumerated by trypan blue exclusion and counting with a hemacytometer. This method was also utilized to enumerate the difference in growth between ZEST and CHEST cells when they were plated in (1) ZEST media or (2) CHEST media.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of CHEST cells

RNA was isolated from CHEST cells using a QIAGEN RNeasy kit, and cDNA was generated using the BioRad iScript cDNA synthesis kit. Primers, product sizes, and annealing temperatures used for the RT-PCR characterization of ZEST cells are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Primer sets used for RT-PCR characterization of CHEST cells.

| Gene | Definition | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tie2 (tek) | TEK tyrosine kinase, endothelial | GAAGTGTGTGTGTGCAAAAG | CAGTGTTGATCTCCACATCC | 55 | 134 |

| kdr | kinase insert domain receptor | TCAGACTCAGAGCTCTTGAG | GACTATAGTAGGGGTCGGTG | 55 | 122 |

| tpo (thpo) | thrombopoietin | ATGGAAAGCAACGTGACTGG | CCACTGCAGATTACCTTTTC | 55 | 178 |

| tnfa | tumor necrosis factor a | GAGAGATCGCATTTCACAAG | TTCCTCAGTCAGTTCAGACG | 55 | 230 |

| kdrl31 | kinase insert domain receptor like | GCCTCGGGTCAATGCTGTTCC | GTCCGGTTGCCAAGTTCATTCC | 60 | 561 |

| flt131 | fms-related tyrosine kinase 1 (vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor receptor) | ATCCGCAGTGTTATATTCCTCCAT | TTGCGCTCCTTTTGCCGATACCT | 60 | 410 |

| angpt131 | angiopoietin 1 | CTACAACAGAGCGCCGTCCAC | AGGTCCTGCTGTCTCTGAAG | 60 | 419 |

| fli1a | fli-1 proto-oncogene, ETS transcription factor a | ATGGACGGAACTATTAAGGAGGC | TTAGTAGTAACTACCAAGGTGTG | 60 | 1355 |

| pecam131 | platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 | GACGGGCACGCTGATGTTTCTCTTC | CTGCACGCTCCCTTTCTCGGTTTTG | 60 | 427 |

| cdh531 | cadherin 5 | CCCCGTTTTCGATTCTGACC | CTTTGAGGCTTAGCATTCCATCTT | 60 | 515 |

| acta1a16 | actin, alpha 1a, skeletal muscle | GAAAAGAGCTACGAGCTTCC | GTAAGTGGTCTCGTGAATGC | 50 | 129 |

| myod116 | myogenic differentiation 1 | ATGGCATGATGGATTTTATG | TTTATTATTCCGTGCGTCAG | 50 | 107 |

| actc1a16 | actin, alpha, cardiac muscle 1a | TGCTGTCTTTCCCTCTATTG | GAGTGAGGATACCCCTCTTG | 50 | 116 |

| acta216 | actin, alpha 2, smooth muscle, aorta | TGGATCTGGACTGTGTAAGG | ACTATCTTTCTGCCCCATTC | 50 | 121 |

| gata1a49 | GATA binding protein 1a | TGAATGTGTGAATTGTGGTG | ATTGCGTCTCCATAGTGTTG | 55 | 650 |

| cd45 (ptprc)49 | protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, C | AGTTCCTGAAATGGAAAAGC | GCACAGAAAAGTCCAGTACG | 55 | 140 |

| ef1a (eef1a1l1)49 | eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha 1, like 1 | GAGAAGTTCGAGAAGGAAGC | CGTAGTATTTGCTGGTCTCG | 55 | 123 |

| epo18 | erythropoietin | ACTTGTAAGGACGATTGCAG | TATCTGTAATGAGCCGATGG | 55 | 156 |

| gcsfa (csf3)10 | colony stimulating factor 3a, granulocyte colony stimulating factor | AACTACATCTGAACCTCCTG | GACTGCTCTTCTGATGTCTG | 55 | 165 |

| gcsfb (csf3b)10 | colony stimulating factor 3b, granulocyte colony stimulating factor b | GGAGCTCTGCGCACCCAACA | GGCAGGGCTCCAGCAGCTTC | 55 | 184 |

| il-11a | interleukin 11a | GACAAGCTGAGCAATCAGAC | GGAGCTGAGAAAGAGTAGGC | 50 | 172 |

| il-11b | interleukin 11b | TTGAACATTCGCTATCATCC | GAGTAATCGTTCCCCAATTC | 50 | 166 |

| m1716 | il-6 subfamily cytokine M17 | CTTGATTGCCGTTCAGTTAG | TGACCGGAGATTGTAGACAC | 50 | 210 |

| fgf118 | fibroblast growth factor 1 | ATACTGCGCATAAAAGCAAC | AGTGGTTTTCCTCCATCTTC | 50 | 154 |

| fgf2118 | fibroblast growth factor 21 | CGGTGGTGTATGTATGTTCC | GTAGCTGCACTCTGGATGAC | 50 | 203 |

| kitlga18 | kit ligand a | GGATTCAATGCTTGACTTTG | TGTACTATGTTGCGCTGATG | 50 | 205 |

| kitlgb16 | kit ligand b | GGCAACCAGTCCACCAATAAG | CACTTTTCCCTTCTGTAGTGGC | 50 | 135 |

| vegfaa16 | vascular endothelial growth factor Aa | GAAACGTCACTATGGAGGTG | TTCTTTGCTTTGACTTCTGC | 50 | 121 |

| bmp1l18 | bone morphogenic protein 1, like | GGATGGATATTGGAGGAAAG | CTTTGTTCGGTCTGTAATCG | 50 | 230 |

| cxcl12a16 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) 12a, stromal cell-derived factor 1a | CGCCATTCATGCACCGATTTC | GGTGGGCTGTCAGATTTCCTTGTC | 50 | 297 |

| cxcl12b16 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) 12b, stromal cell-derived factor 1b | CGCCTTCTGGAGCCCAGAGA | AGAGATTCTCCGCTGTCCTCC | 50 | 291 |

| il-1b16 | interleukin 1, beta | TCCACATCTCGTACTCAAGG | CAGCTCGAAGTTAATGATGC | 50 | 227 |

| ifnɣ16 | interferon, gamma 1-2 | TACATAATGCACACCCCATC | TCCTTTGTAGCTTCATCCAC | 55 | 158 |

| il-2618 | interleukin 26 | TGAAAAGATGTGGGATGAAC | ACTGATCCACAGCAAAACAC | 55 | 214 |

| il-1518 | interleukin 15, like | CCAAGTCCACAATTACATGC | TCTTTGTAGAGCTCGCAGAC | 55 | 166 |

| il-12a18 | interleukin 12a | GTGAGTCTGCTGAAGGAGTG | AGTGACATCATTTCCTGTGC | 50 | 167 |

| il-1018 | interleukin 10 | ATGAATCCAACGATGACTTG | TCTTGCATTTCACCATATCC | 50 | 222 |

| il-22 | interleukin 22 | CTACCTGCGATATGAAGTGC | GAAATATGGAAGCAGTCGTG | 50 | 171 |

| dla18 | δA | ACGACGATTTGAGTATGACG | GGGATTGGCACTTTATATCC | 50 | 186 |

| dlb18 | δB | TTCCGTGTTTAATGATTTGG | CACTCCACAGAAACTCTTGC | 50 | 158 |

| dlc18 | δC | TGGTGGACTACAATCTGAGC | ACCTCAGTAGCAAACACACG | 50 | 169 |

| dld16 | δD | AACCCAGACCGTCTGATCAGT | CCGGGTTTGTCGCAAAAGCCA | 50 | 308 |

| dll418 | δ-like 4 | CTCTTTCAGCACACCAATTC | TGAACATCCTGAGACCATTC | 50 | 189 |

| jag1a18 | jagged 1a | TGATTGGTGGATACTTCTGC | AATCCATTGAGTGTGTCCTG | 55 | 238 |

| jag1b18 | jagged 1b | CTGTGAGCCATCTTCTTCAG | AGCAAAGGAACCAGGTAGTC | 55 | 213 |

| jag218 | jagged 2 | AATGACTGTGTGAGCAATCC | GTCATTGACCAGATCCACAC | 50 | 174 |

| mpx50 | myeloid-specific peroxidase | TGATGTTTGGTTAGGAGGTG | GAGCTGTTTTCTGTTTGGTG | 55 | 158 |

| pax5 | paired box 5 | GACCCTCTCCAGGATTCTCC | TGGGGTTTGACCAGGAAATA | 60 | 501 |

| lck | LCK proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase | GCCAGAGGGGTTACATACCA | TGATAGCCACTTGACGGTTG | 60 | 501 |

| cmyb (myb) | v-myb avian myeloblastosis viral oncogene homolog | AAGACCAACGGGTGATTGAG | CAGTGCCATGTTGTGGAAAG | 60 | 507 |

| cd41 (itga2b)49 | Integrin, alpha 2b | CTGAAGGCAGTAACGTCAAC | TCCTTCTTCTGACCACACAC | 55 | 197 |

| band3 (slc4a1a) | solute carrier family 4 (anion exchanger), member 1a (Diego blood group) | CAACTTCCAGAAGAAGATG | TTGACCATACCACCAAATG | 55 | 144 |

| igm (ighm)50 | immunoglobulin heavy constant mu | AGCTTCTCTAGCTCCACCAG | ATTTTGGTGAAATGGAATTG | 55 | 477 |

Isolation and enumeration of WKM

WKM was isolated as described previously15,27 and enumerated by trypan blue exclusion and counting with a haemocytometer. To enumerate WKM cells after being cultured on CHEST cells, the stroma was gently rinsed to remove the WKM from the cell monolayers. Cells were concentrated by centrifugation at 300 g, cytospun onto slides, stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa, and visualized by microscopy.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

WKM was isolated and resuspended in PBS with 0.9% foetal bovine serum. Lymphoid and precursor fractions were sorted and analysed on an Influx high speed sorter (BD Biosciences) by utilizing their unique forward and side scatter characteristics19. Sytox red (Life technologies) was used as a cell viability stain.

Immunofluorescence

CHEST cells were grown on glass coverslips in culture media in 24-well tissue culture plates. When cells reached 100% confluence, they were fixed and stained with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and left overnight at 4 °C. Slides were permeabilized with PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (PBT) for 10 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and blocked with 1% BSA in PBT for 1 hour. Cells were incubated with mouse ZO-1 monoclonal antibody (1:100 dilution; Invitrogen) overnight, washed three times in PBT, incubated with goat-anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 594 secondary (1:200 dilution; Life Technologies) and DAPI (1:1000 dilution), washed three times in PBT, cover slipped, and visualized by fluorescent microscopy27.

Matrigel assays

CHEST cells were plated onto Matrigel precoated 6-well plates (Corning) and incubated at 32 °C for 24 hours in endothelial growth medium-2 (Lonza) followed by brightfield microscopy. After cells were imaged, they were trypsinized, RNA was isolated with a QIAGEN RNeasy kit, and cDNA was generated using the BioRad iScript cDNA synthesis kit for RT-PCR analysis.

Statistics

Two tailed heteroscedastic student t tests were performed to determine statistical significance.

Results

Generation and characterization of hematopoietic-supportive stromal cells

To generate a hematopoietic-supportive stromal cell line, we isolated cells from the caudal hematopoietic tissue (CHT) region of zebrafish, where hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) expand in early embryonic development. Tissue posterior to the yolk tube extension of 72 hpf fish was surgically removed, finely diced, and plated in tissue-culture flasks with media supplemented with selenium and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) (Fig. 1A). As with ZKS and ZEST cultures, these cells were grown at 32 °C in a humidified, 5% CO2 environment. These caudal hematopoietic embryonic stromal tissue (CHEST) cells divided every 36–48 hours, and grew continuously in culture. We have grown these cells for over 200 passages, and never observed any senescence. Additionally, there was no survival crisis during the early stages of growth, indicating that the cells likely did not derive from a clonal population of cells that survived culture conditions. The cells that grew from this explanted tissue had a stromal morphology (Fig. 1B) when grown on glass coverslips and stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa and appeared homogenous. Importantly, there were no visible hematopoietic cells present in the culture (Fig. 1B, bottom). To confirm that CHEST cells were not contaminated with hematopoietic cells and also to examine if they were spontaneously producing blood, we examined CHEST cells by RT-PCR. gata1, cd45, mpx, lck, pax5, and cmyb transcripts were not detected in these cultures, indicating that there were no red blood cells, leukocytes, or HSPCs present (Fig. 1Ci), confirming their stromal nature.

To determine if CHEST cells had the capability to support haematopoiesis, we examined their transcript expression by RT-PCR. CHEST cells produce several zebrafish cytokines important for blood cell development including erythropoietin (epo28), granulocyte colony stimulating factor (gcsf10,29), and thrombopoietin (tpo12) (Fig. 1Cii). They also expressed hematopoietic supportive cytokines such as il11a and b, fgf1, fgf21, kit ligands, and cxcl12a and b (Fig. 1Cii). CHEST cells expressed inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 1Ciii), including tnfa, recently implicated in the formation of HSCs30. CHEST cells also expressed a multitude of Notch signalling pathway mediators (Fig. 1Civ) and skeletal muscle markers (Fig. 1Cv). Importantly, they also expressed several markers of smooth muscle and endothelial cells, including acta2, tie2, kdr, and kdrl but not the cardiac-specific muscle marker actc1a (Fig. 1Cvi). Together, these data indicated that CHEST cells expressed a multitude of hematopoietic-supportive cytokines, inflammatory molecules, and Notch signalling mediators that would likely support blood development.

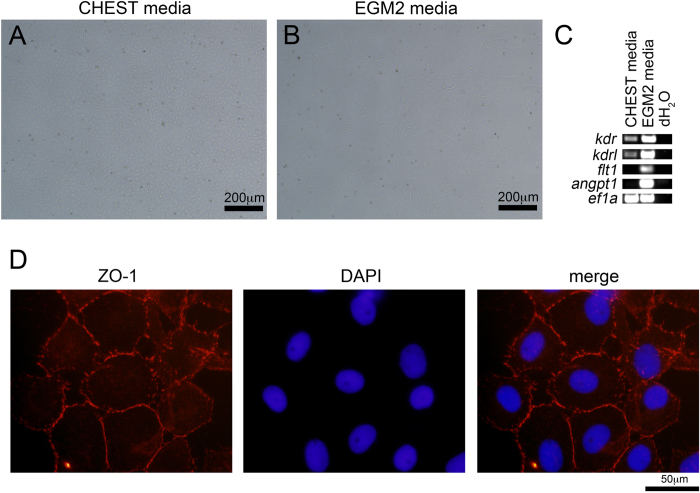

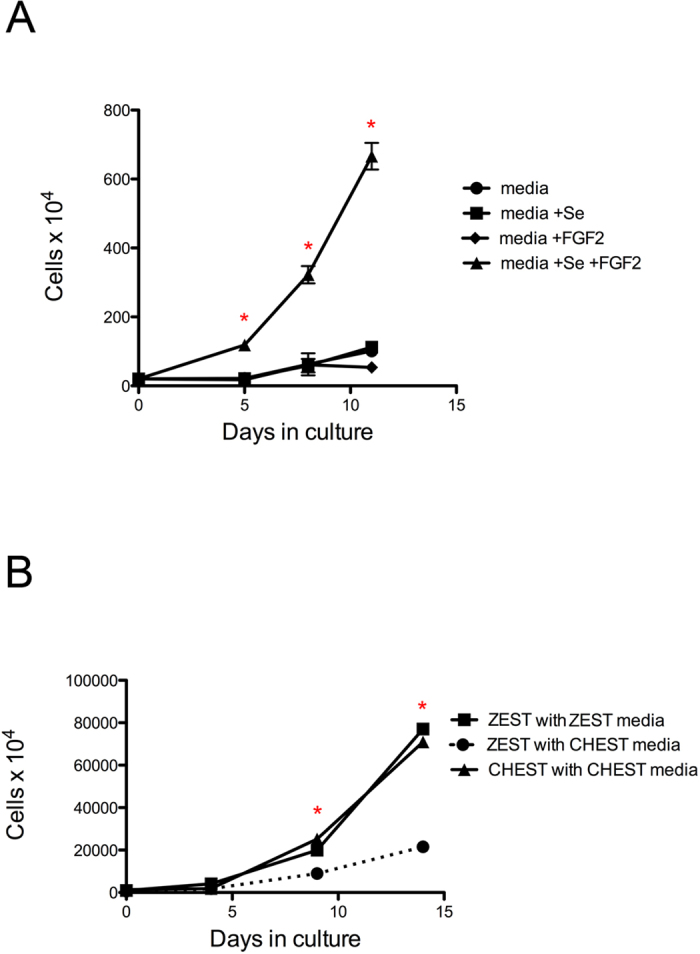

As CHEST cells expressed several markers of endothelial cells (Fig. 1Cvi), we examined if they would also form capillary networks when plated on Matrigel-coated plates with endothelial growth media-2 (EGM2), which is a capability of cells with endothelial potential31,32,33. When CHEST cells were plated on standard tissue culture plates in CHEST media, no branching activity after 24 hours was observed (Fig. 2A). However, when plated on Matrigel in EGM2 media, cellular elongation, a property of endothelial-like cells, was observed (Fig. 2B). To further examine the cells’ endothelial-like nature, we harvested them after 24 hours in culture and performed RT-PCR for kdr, kdrl, flt1, and angpt1, all of which were upregulated in endothelial growth conditions (Fig. 2C). To examine if CHEST cells would form tight junctions in vitro, a characteristic of confluent endothelial monolayers34 and an essential component of angiogenesis and barrier formation of primary endothelial cells35, immunoblotting with a monoclonal antibody directed against zona occludens 1 (ZO-1) was performed, indicating that CHEST cells did form tight junctions between one another when grown at high confluence in culture (Fig. 2D). CHEST cells also had unique growth properties in different media formulations. CHEST cells do not proliferate well in ZKS/ZEST media16,18 (Fig. 3A), and multiple attempts to derive them in this media failed (data not shown). Prior studies culturing zebrafish endothelial stromal cells added selenium and FGF2 to the culture media31, so we also added these supplements. Media with either selenium or FGF2 added did not significantly increase the growth rate of CHEST cells. Instead, both additives were required for optimal growth (Fig. 3A). Importantly, the combinatorial addition of selenium and FGF2 is not universally supportive of stromal cell lines; growing ZEST cells in this media did not support ZEST cell expansion as well as CHEST cell expansion (Fig. 3B). Together, these RT-PCR, immunohistochemical staining, and growth condition data indicate that CHEST cells have endothelial-like properties and are different types of stromal cells than previously derived embryonic primary stromal cell lines.

Figure 2. CHEST cells have endothelial-like properties.

(A) Images of CHEST cells grown on tissue culture plates with CHEST growth media and (B) on Matrigel with EGM2 endothelial growth media. Images taken at 200x, scale bar is 200 μm. (C) RT-PCR performed on CHEST cells from (A) and (B) for endothelial-specific transcripts. (D) ZO-1 staining (red, left panel), DAPI staining (blue, middle panel), and merged image (right panel) of CHEST cells grown to confluence in CHEST media. Images taken at 1000x, scale bar is 50 μm.

Figure 3. CHEST cells uniquely require selenium and FGF2 for their proliferation.

(A) CHEST cells were enumerated at various times after culture in media (black circles; n = 3), media with selenium (+Se, black squares; n = 3), media with FGF2 (black diamonds; n = 3), or media with Se and FGF2 (black triangles; n = 3). Error bars denote standard error of the mean. * denotes p < 0.005 when comparing cells grown with CHEST media supplemented with selenium and FGF2 to either of the three other samples. (B) ZEST cells were enumerated at various times after culture in ZEST media (black squares; n = 3) and in media with selenium and FGF2 (CHEST media, black circles, dashed line; n = 3). CHEST cells grown in CHEST media (black triangles; n = 3) is shown as a control. Error bars denote standard error of the mean. * denotes p < 0.005 when comparing ZEST cells grown in CHEST media to either of the two other samples.

CHEST cells encourage proliferation of hematopoietic cells in vitro

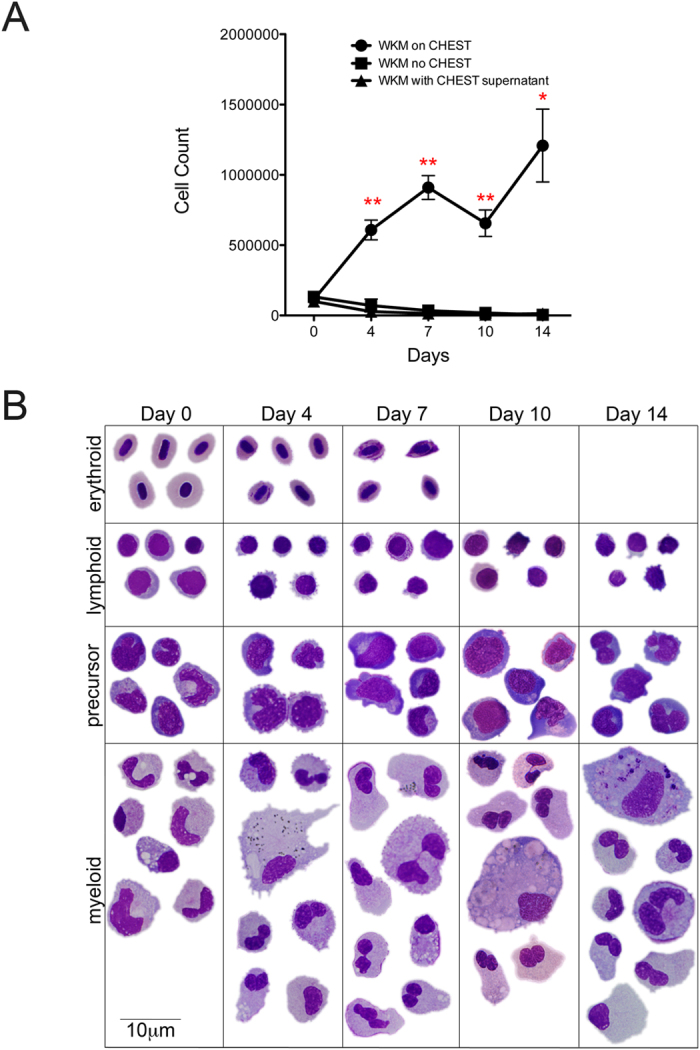

To determine if CHEST cells would support haematopoiesis and the expansion of zebrafish blood cells, we isolated WKM from the kidney, which is the main site of adult teleost haematopoiesis. WKM was plated on CHEST cells that were 80% confluent, and cell counts and cytocentrifuge preparations were performed at days 4, 7, 10, and 14 of culture. Cells plated on CHEST stroma increased over two weeks, while WKM with no stromal support died off during the same time period (Fig. 4A). To confirm that the cells that proliferated were hematopoietic, we also cytocentrifuged the samples at each time point and stained them with May Grünwald-Giemsa. At each time point, cells with lymphoid, precursor, and myeloid morphologies were identified (Fig. 4B and Table 2). Mature red blood cells were identified up to day 7 in culture, likely due to a lack of exogenous fish transferrin being added to the culture; this lack of mature red blood cell maintenance was not surprising, and was also seen in ZKS and ZEST cells16,18. As with ZKS and ZEST cells, the support of haematopoiesis was dependent on cell-cell contact; simply removing CHEST cell conditioned media and adding it to WKM was not enough to support their survival (Fig. 4A). To ensure that the CHEST cells were not a mixed population of cells with varying hematopoietic-supportive qualities, a limiting dilution of the original CHEST culture generated ten different clonal lines. All of these clones expanded WKM numbers in a similar manner (data not shown), indicating that the CHEST cells are homogenous and not comprised of mixed cell populations that have variable hematopoietic supportive qualities. Overall, these data indicate that CHEST cells support the proliferation and maintenance of adult zebrafish hematopoietic cells.

Figure 4. CHEST cells support hematopoietic expansion.

(A) WKM from adult zebrafish was plated on CHEST cells and enumerated at various times (black circles; n = 8), plated in culture with no stromal under layer (black squares; n = 6), or plated with no CHEST cells in CHEST cell supernatant media (black triangles; n = 3). Error bars denote standard error of the mean. * denotes p < 0.005 and ** denotes p < 0.0005 when comparing cells grown on CHEST cells to either of the two other samples. (B) Composite May-Grünwald Giemsa images of hematopoietic cells isolated from the cultures (1000x, scale bar is 10 μm).

Table 2. Differential counts of haematopoietic differentiation on CHEST cells.

| Days in culture | Cells plated on CHEST | Cell types counted after culture on CHEST cells |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erythroid | Lymphoid | Precursor | Myeloid | Total cells | ||

| 0 | WKM | 65 (44.2%) | 14 (9.5%) | 20 (13.6%) | 48 (32.7%) | 147 |

| Precursor fraction | 1 (0.5%) | 7 (3.4%) | 195 (94.2%) | 4 (1.9%) | 207 | |

| Lymphoid fraction | 2 (1.3%) | 150 (96.8%) | 3 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | 155 | |

| 3 | WKM | 186 (22.1%) | 122 (14.5%) | 131 (15.6%) | 402 (47.9%) | 840 |

| Precursor fraction | 19 (6.1%) | 13 (4.2%) | 75 (24%) | 205 (65.7%) | 312 | |

| Lymphoid fraction | 11 (3.4%) | 78 (24.5%) | 82 (25.7%) | 148 (46.4%) | 319 | |

| 7 | WKM | 39 (6%) | 86 (13.2%) | 95 (14.5%) | 433 (66.3%) | 653 |

| Precursor fraction | 2 (1%) | 18 (8.8%) | 53 (26%) | 131 (64.2%) | 204 | |

| Lymphoid fraction | 5 (3%) | 46 (27.2%) | 24 (14.2%) | 94 (55.6%) | 169 | |

| 11 | WKM | 18 (3.4%) | 76 (14.2%) | 112 (21%) | 331 (61.6%) | 537 |

| Precursor fraction | 1 (0.5%) | 22 (10.9%) | 26 (12.9%) | 150 (74.6%) | 201 | |

| Lymphoid fraction | 1 (0.7%) | 41 (28.9%) | 9 (6.3%) | 91 (64.1%) | 142 | |

| 14 | WKM | 2 (0.7%) | 42 (14.1%) | 68 (22.8%) | 186 (62.4%) | 298 |

| Precursor fraction | 1 (0.6%) | 20 (11.7%) | 19 (11.1%) | 131 (76.6%) | 171 | |

| Lymphoid fraction | 0 (0%) | 48 (38.1%) | 16 (12.7%) | 62 (49.2%) | 126 | |

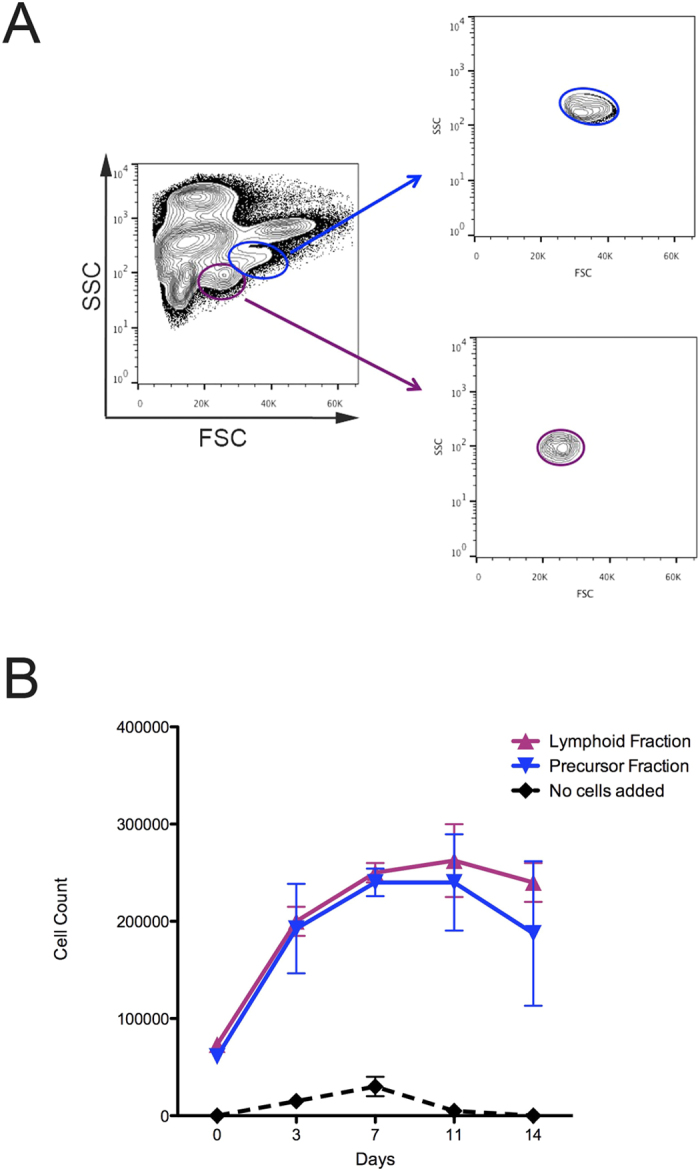

CHEST cells support the proliferation and differentiation of HSPCs

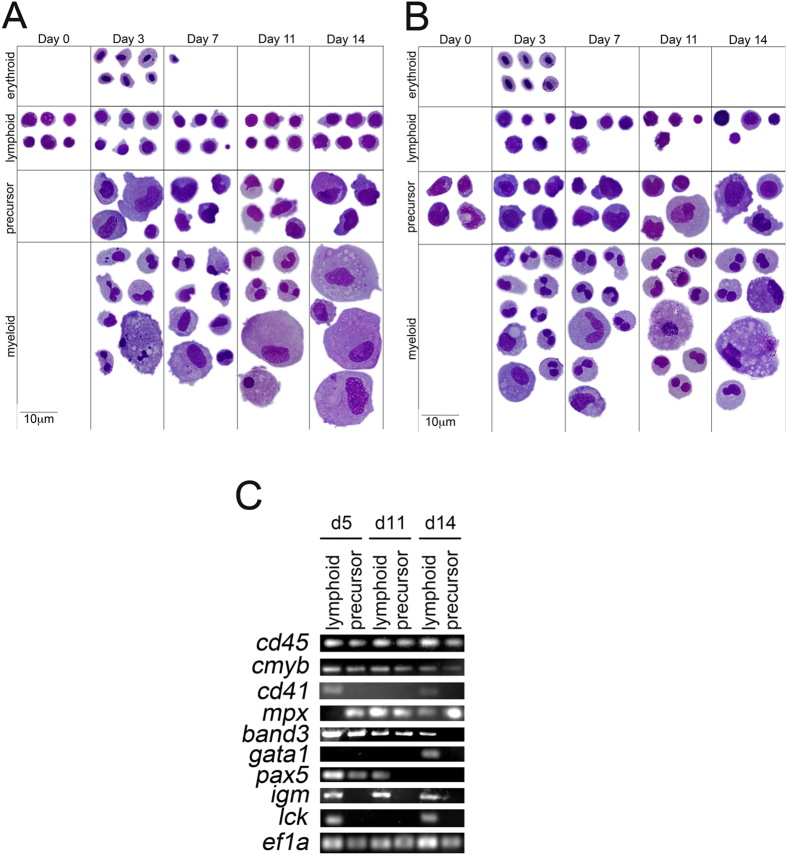

To determine if CHEST cells could also encourage the proliferation and differentiation of HSPCs, the lymphoid (Fig. 5A, purple line) and precursor (Fig. 5A, blue line) fractions of adult WKM were isolated by FACS. The lymphoid population contains not only mature lymphoid cells, but also HSPCs and HSCs, while the precursor population contains HSPCs that can give rise to erythroid, myeloid, and lymphoid cell populations. These populations were validated to be over 95% pure (Fig. 5A), after which they were plated on top of 80% confluent CHEST cells. At days 3, 7, 11, and 14, cell counts were performed, indicating that both populations were expanding on CHEST stroma (Fig. 5B). To confirm that these progenitor populations were also differentiating into mature erythroid, lymphoid, and myeloid populations, cells were cytocentrifuged at each time point. The lymphoid cell population maintained lymphoid cells throughout two weeks, but also differentiated into more mature precursor cells and finally into erythrocytes and myeloid cells (Fig. 6A and Table 2). In a similar fashion, the precursor population generated mature erythroid, lymphoid, and myeloid cells over the two-week experiment (Fig. 6B). To confirm the expression of mature cell markers during the differentiation time course, another experiment was performed and cells were isolated at days 5, 11, and 14 and subjected to RT-PCR. In each population, cd45+ leukocytes were detected, as well as cells expressing cmyb, a marker of HSPCs (Fig. 6C). All populations also expressed erythromyeloid markers such as cd41, mpx, band3, or gata1. igm+ mature B cells were only seen in lymphoid populations, as were lck+ T cells. While pax5, an early marker of B cell differentiation was seen in the day 5 precursor population, this marker was not seen at later time points of the experiment. Together, these data indicate that CHEST cells expanded and differentiated a multitude of hematopoietic cell types over two weeks. While all cell types were observed morphologically, RT-PCR and differential counts data indicate that CHEST cells favor the differentiation and proliferation of myeloid cells over the two-week experimental period.

Figure 5. CHEST cells expand HSPCs in culture.

(A) FACS isolation schematic. Precursor fraction (blue) isolated from WKM (left panel) was reanalysed after sorting and deemed to be over 95% pure (right panel). Lymphoid fraction (purple) isolated from WKM (left panel) was reanalysed after sorting and deemed to be over 95% pure (right panel). (B) Cultures started from the lymphoid fraction (purple triangles, n = 3) and precursor fraction (blue triangles, n = 3) were enumerated over time in culture on CHEST cells. Cultures with no fractions added were also counted to ensure that CHEST cells were not spontaneously generating hematopoietic cells (black diamonds, n = 3).

Figure 6. CHEST cells encourage differentiation of HSPCs in culture.

(A) Composite May-Grünwald Giemsa images of hematopoietic cells isolated from the lymphoid fraction in Fig. 5 (1000x, scale bar is 10 μm). (B) Composite May-Grünwald Giemsa images of hematopoietic cells isolated from the precursor fraction in Fig. 5 (1000x, scale bar is 10 μm). (C) RT-PCR of leukocyte- (cd45), progenitor- (cmyb), erythromyeloid- (cd41, mpx, band3, and gata1), B cell- (pax5 and igm), and T cell- (lck) specific transcripts isolated from the cultures as in A and B. Gel images have been cropped for clarity of presentation.

Discussion

Zebrafish have been utilized extensively to study haematopoiesis: they develop externally and are optically transparent, allowing the visualization of blood formation. Importantly, zebrafish are fecund and genetically amenable, allowing large-scale mutagenesis and chemical screens for elucidating genes and molecular pathways involved in haematopoiesis to be performed. As zebrafish share a multitude of hematopoietic-supportive molecular pathways with other vertebrates (reviewed in ref. 13), findings in the zebrafish have utility for understanding human disease. However, while forward genetic screens have been utilized to identify genes essential for the generation of primitive blood and the emergence of HSCs, they have not elucidated genes essential for HSPC proliferation and differentiation due to a lack of methodologies to functionally assess them. To address this caveat we previously generated cell lines from the adult zebrafish kidney (ZKS cells18) and from the site of HSC emergence in the developing embryo (ZEST cells16), which allowed us to develop clonal methylcellulose assays to examine cytokine signalling and HSPC differentiation10,11,12. While ZKS and ZEST cells have proven effective as a way to develop and discover new cytokines involved in haematopoiesis, they are not the only hematopoietic niches that exist in the developing zebrafish. In our quest to generate multiple hematopoietic-supportive cell lines, we also isolated and cultured CHEST cells.

CHEST cells are of interest because of the unique hematopoietic niche that they are isolated from. First described over 10 years ago, the CHT is a transient anatomical location surrounding a plexus comprised of endothelial and fibroblastic reticular cells25. This location is similar to the murine FL, in that HSCs that extravasate from the dorsal aorta travel to and become lodged in the CHT plexus to expand their numbers. From there, these cells emigrate to either seed the kidney, which is the main site of adult haematopoiesis in the zebrafish, or they travel to the thymus to differentiate into T cells. Recent work indicates that the plexus of the CHT is dynamic, and that when HSPCs lodge there, perivascular endothelial cells remodel so that they surround the HSPCs to form a stem cell “pocket36.” Referred to as “endothelial cuddling,” this behaviour has also been visualized in the mouse FL36.

Interestingly, CHEST cells share many qualities with the perivascular cells described in these previous reports, indicating that they are likely perivascular in nature. To visualize “endothelial cuddling,” Tamplin et al. utilized a transgenic zebrafish whereby the promoter of cxcl12a drove DsRed fluorescence36; CHEST cells express this important chemokine. CHEST cells also express kitlgb, a chemokine expressed in the CHT and required for HSPC expansion in this region37. Importantly, CXCL12 and KITLG are known HSPC-supportive factors produced in the stromal perivascular niche of mammalian bone marrow38,39,40. Recent findings indicate that the CHT region expresses tpo and gcsf37, which are cytokines essential for HSPC proliferation10,12 that are also generated by CHEST cells. Like CHEST cells, perivascular cells also produce VEGF which stimulates endothelial cell survival41. Based on the tight binding between the cells that comprise the vascular niche of the CHT36, it is not surprising that CHEST cells express ZO-1, a central regulator of endothelial junctions that regulates cell migration and barrier formation35. Finally, CHEST cells elongate when plated on Matrigel coated plates, upregulating and expressing endothelial transcripts in these conditions, indicating their perivascular nature.

Although CHEST cells support haematopoiesis in vitro, they are distinct from other hematopoietic-supportive stromal cell lines that we have isolated and characterized. First, they are dependent on FGF2 and selenium present in the growth media, which slow the growth of ZEST cells. FGF2 and selenium were required for the generation of other zebrafish endothelial cell lines31,42, and have been implicated in angiogenesis43, HSPC expansion44, and cytokine-induced expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells45,46. When we tried to derive CHEST cells without FGF2 and selenium we were unsuccessful. Additionally, differentiating hematopoietic cells on CHEST without these media supplements proved fruitless. While CHEST cells express similar hematopoietic-supportive cytokine transcripts when compared to ZKS and ZEST cells, CHEST cells also express endothelial-specific markers such as tie2, kdr, kdrl, and vegfaa. One of the most striking differences between CHEST, ZKS, and ZEST cells is that CHEST cells seem to weakly direct mature lymphoid differentiation. While lymphoid cells could survive over a two-week incubation time, and were detected morphologically when we plated HSPCs onto CHEST cells, no definitive lymphoid cell markers were detected. This is in agreement with studies that indicate cellular immigrants to the thymus that left the CHT did not express rag125; these cells did not differentiate in the CHT, but needed to mature in the thymus. Likewise, mature B cells are not seen in the zebrafish embryo until 3 weeks post-fertilization47, but the CHT is only hematopoietic until 2 weeks post-fertilization25. We believe that this is likely due to the fact that zebrafish HSCs and HSPCs have morphological characteristics of lymphoid cells15,19; when isolated and stained they look very similar. They even have the same light scatter and granularity as lymphoid cells19, preventing easy isolation/identification from B and T cells with FACS. In essence, even though we observed cells that were morphologically “lymphoid” in our differentiation assays, they were likely HSPCs, as these cell types have similar appearances. This is further bolstered by the expression of cmyb throughout the experiment, while no definitive B and T cell transcripts were detected. In the future, it will be of interest to transplant these “lymphoid” cells back into zebrafish and show short-term or long-term engraftment, which is the gold standard for proving HSPC or HSC identity, respectively.

In the future, it will be of interest to compare the transcriptome of CHEST cells to other hematopoietic-supportive cell lines in the zebrafish16,18 to determine what signals are shared amongst these cells, and what signals are unique. It will also be of interest to compare the signalling properties to thymic epithelium, the site of T cell differentiation, to see what properties exist in these distinct tissues that support HSPCs differentiating into mature lymphoid cells. Finally, it would be useful to compare these to other hematopoietic-supportive stromal cell lines and perivascular-derived mesenchymal stromal cell lines previously generated31,42. The goal of all of these studies would be to eventually compare the transcriptome of these zebrafish cell lines to the mammalian sites of haematopoiesis. Investigations have elucidated a core molecular network of mRNA transcripts required for HSPC support in murine cell lines48, and it would be of interest to compare the expression of genes shared amongst vertebrate phyla involved in HSPC support. Undoubtedly these shared transcripts will shed light on genes essential for the process of HSPC generation, proliferation, and differentiation, as they have likely been conserved over the past 400+ million years of vertebrate evolution.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wolf, A. et al. Zebrafish Caudal Haematopoietic Embryonic Stromal Tissue (CHEST) Cells Support Haematopoiesis. Sci. Rep. 7, 44644; doi: 10.1038/srep44644 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen Ong (UCSD) and Betsey Tamietti (CSUC) for excellent animal care and laboratory management. We also thank Jonathan Van Dyke at the University of California Davis Flow Cytometry Core for cell sorting. This research was supported by the NIH (K01-DK087814-01A1 to D.L.S. and R01-DK074482 to D.T.), a California State University Chico Internal Research Grant (to D.L.S.), and a Student Research and Creativity Award from California State University, Chico (to J.A.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions A.W., J.A., C.C., F.W., G.M. and D.L.S. performed research. D.L.S. and D.T. designed the research. D.L.S. wrote the manuscript based on a first draft from A.W.

References

- Akashi K., Traver D., Miyamoto T. & Weissman I. L. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature 404, 193–197 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo M., Weissman I. L. & Akashi K. Identification of clonogenic common lymphoid progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Cell 91, 661–672 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori Y. et al. Identification of the human eosinophil lineage-committed progenitor: revision of phenotypic definition of the human common myeloid progenitor. J Exp Med 206, 183–193, doi: 10.1084/jem.20081756 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakorn T. N., Miyamoto T. & Weissman I. L. Characterization of mouse clonogenic megakaryocyte progenitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100, 205–210, doi: 10.1073/pnas.262655099 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulais P. E. & Frenette P. S. Making sense of hematopoietic stem cell niches. Blood 125, 2621–2629, doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-570192 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison S. J. & Spradling A. C. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell 132, 598–611, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.038 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel M. J. & Morrison S. J. Uncertainty in the niches that maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Rev Immunol 8, 290–301, doi: 10.1038/nri2279 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciau-Uitz A., Monteiro R., Kirmizitas A. & Patient R. Developmental hematopoiesis: ontogeny, genetic programming and conservation. Exp Hematol 42, 669–683, doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2014.06.001 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traver D. Cellular dissection of zebrafish hematopoiesis. Methods Cell Biol 76, 127–149 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachura D. L. et al. The zebrafish granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (Gcsfs): 2 paralogous cytokines and their roles in hematopoietic development and maintenance. Blood 122, 3918–3928, doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-475392 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachura D. L. et al. Clonal analysis of hematopoietic progenitor cells in the zebrafish. Blood 118, 1274–1282, doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-331199 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda O. et al. Dissection of vertebrate hematopoiesis using zebrafish thrombopoietin. Blood 124, 220–228, doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-564682 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements W. K. & Traver D. Signalling pathways that control vertebrate haematopoietic stem cell specification. Nat Rev Immunol 13, 336–348, doi: 10.1038/nri3443 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North T. E. et al. Prostaglandin E2 regulates vertebrate haematopoietic stem cell homeostasis. Nature 447, 1007–1011, doi: 10.1038/nature05883 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachura D. L. & Traver D. Cellular dissection of zebrafish hematopoiesis. Methods Cell Biol 133, 11–53, doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2016.03.022 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C. et al. Zebrafish embryonic stromal trunk (ZEST) cells support hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Exp Hematol 43, 1047–1061, doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2015.09.001 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand J. Y. et al. Haematopoietic stem cells derive directly from aortic endothelium during development. Nature 464, 108–111, doi: 10.1038/nature08738 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachura D. L. et al. Zebrafish kidney stromal cell lines support multilineage hematopoiesis. Blood 114, 279–289 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traver D. et al. Transplantation and in vivo imaging of multilineage engraftment in zebrafish bloodless mutants. Nat Immunol 4, 1238–1246, doi: 10.1038/ni1007 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumano A. & Godin I. Ontogeny of the hematopoietic system. Annu Rev Immunol 25, 745–785, doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141538 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzierzak E. The emergence of definitive hematopoietic stem cells in the mammal. Curr Opin Hematol 12, 197–202 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller G., Lacaud G. & Robertson S. Development of the hematopoietic system in the mouse. Exp Hematol 27, 777–787 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G. R. & Moore M. A. Role of stem cell migration in initiation of mouse foetal liver haemopoiesis. Nature 258, 726–728 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houssaint E. Differentiation of the mouse hepatic primordium. II. Extrinsic origin of the haemopoietic cell line. Cell Differ 10, 243–252 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama E. et al. Tracing hematopoietic precursor migration to successive hematopoietic organs during zebrafish development. Immunity 25, 963–975, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.015 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book. A guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Danio rerio). 4th ed., Univ. of Oregon Press, Eugene. (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Stachura D. L. & Traver D. Cellular dissection of zebrafish hematopoiesis. Methods Cell Biol 101, 75–110, doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387036-0.00004-9 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paffett-Lugassy N. et al. Functional conservation of erythropoietin signaling in zebrafish. Blood 110, 2718–2726 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liongue C., Hall C. J., O’Connell B. A., Crosier P. & Ward A. C. Zebrafish granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor signaling promotes myelopoiesis and myeloid cell migration. Blood 113, 2535–2546, doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171967 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espin-Palazon R. et al. Proinflammatory signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell emergence. Cell 159, 1070–1085, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.031 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund T. C. et al. Zebrafish stromal cells have endothelial properties and support hematopoietic cells. Exp Hematol 40, 61–70 e61, doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.09.005 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutova I., George J., Kleinman H. K. & Benton G. The endothelial cell tube formation assay on basement membrane turns 20: state of the science and the art. Angiogenesis 12, 267–274, doi: 10.1007/s10456-009-9146-4 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y., Kleinman H. K., Martin G. R. & Lawley T. J. Role of laminin and basement membrane in the morphological differentiation of human endothelial cells into capillary-like structures. J Cell Biol 107, 1589–1598 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. X. & Poznansky M. J. Characterization of the ZO-1 protein in endothelial and other cell lines. J Cell Sci 97 (Pt 2), 231–237 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornavaca O. et al. ZO-1 controls endothelial adherens junctions, cell-cell tension, angiogenesis, and barrier formation. J Cell Biol 208, 821–838, doi: 10.1083/jcb.201404140 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamplin O. J. et al. Hematopoietic stem cell arrival triggers dynamic remodeling of the perivascular niche. Cell 160, 241–252, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.032 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahony C. B., Fish R. J., Pasche C. & Bertrand J. Y. tfec controls the hematopoietic stem cell vascular niche during zebrafish embryogenesis. Blood, doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-04-710137 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L., Saunders T. L., Enikolopov G. & Morrison S. J. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 481, 457–462, doi: 10.1038/nature10783 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Ferrer S. et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature 466, 829–834, doi: 10.1038/nature09262 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L. & Morrison S. J. Haematopoietic stem cells and early lymphoid progenitors occupy distinct bone marrow niches. Nature 495, 231–235, doi: 10.1038/nature11885 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinmuth N. et al. Induction of VEGF in perivascular cells defines a potential paracrine mechanism for endothelial cell survival. FASEB J 15, 1239–1241 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund T. C. et al. sdf1 Expression reveals a source of perivascular-derived mesenchymal stem cells in zebrafish. Stem Cells 32, 2767–2779, doi: 10.1002/stem.1758 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seghezzi G. et al. Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) induces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in the endothelial cells of forming capillaries: an autocrine mechanism contributing to angiogenesis. J Cell Biol 141, 1659–1673 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itkin T. et al. FGF-2 expands murine hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells via proliferation of stromal cells, c-Kit activation, and CXCL12 down-regulation. Blood 120, 1843–1855, doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-394692 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F. et al. Inhibition of TNF-alpha induced ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin expression by selenium. Atherosclerosis 161, 381–386 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. B., Han J. Y., Jiang W. & Wang J. Selenium inhibits high glucose-induced cyclooxygenase-2 and P-selectin expression in vascular endothelial cells. Mol Biol Rep 38, 2301–2306, doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0362-1 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page D. M. et al. An evolutionarily conserved program of B-cell development and activation in zebrafish. Blood 122, e1–11, doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-471029 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbord P. et al. A systems biology approach for defining the molecular framework of the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell 15, 376–391, doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.005 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand J. Y., Kim A. D., Teng S. & Traver D. CD41 + cmyb + precursors colonize the zebrafish pronephros by a novel migration route to initiate adult hematopoiesis. Development 135, 1853–1862, doi: 10.1242/dev.015297 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittamer V., Bertrand J. Y., Gutschow P. W. & Traver D. Characterization of the mononuclear phagocyte system in zebrafish. Blood 117, 7126–7135, doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-321448 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]