Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a long-term condition in which the kidneys do not work correctly. It has a high prevalence and represents a serious hazard to human health and estimated to affects hundreds of millions of people. Diabetes and hypertension are the two principal causes of CKD. The progression of CKD is characterized by the loss of renal cells and their replacement by extracellular matrix (ECM), independently of the associated disease. Thus, one of the consequences of CKD is glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis caused by an imbalance between excessive synthesis and reduced breakdown of the ECM. There are many molecules and cells that are associated with progression of renal fibrosis e.g. angiotensin II (Ang II). Therefore, in order to understand the biopathology of renal fibrosis and for the evaluation of new treatments, the use of animal models is crucial such as: surgical, chemical and physical models, spontaneous models, genetic models and in vitro models. However, there are currently no effective treatments for preventing the progression of renal fibrosis. Therefore it is essential to improve our knowledge of the cellular and molecular mechanisms of the progress of renal fibrosis in order to achieve a reversion/elimination of renal fibrosis.

Keywords: Rats, mice, disease, kidneys, renal function, review

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) represents a serious hazard to human health, and has a high prevalence. In developed countries, it is estimated that more than 10% of adults present some degree of CKD (1). Despite a varied initial evolution, which is related to the diversity of its aetiologies – namely genetics, autoimmune-related infections, environmental factors, diet, and drugs – progressive renal disease frequently results in renal fibrosis and finally in renal failure. The mechanisms implicated in renal fibrosis are still poorly understood, and existing therapies are ineffective or only slightly successful, hence it is essential to understand the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the usual development of CKD, and to discover and better understand new strategies for treating this disease. In order to study the biopathology of this disease and to evaluate new treatments, animal models are required. The perfect animal model for renal disease research should have human-like renal anatomy, haemodynamics and physiology, as well as enabling the determination of relevant renal, biochemical and haemodynamic parameters. In all probability, no species can consistently meet all these requirements, and the experimental plan and other constraints often determine the choice of animal models for particular research applications. With this in mind, this review aims to describe and analyze animal models of renal fibrosis and suggest new areas of research.

Renal Fibrosis: Aetiology and Pathophysiology

Diabetes and hypertension are currently the two principal causes of CKD (2), among other causes such as infectious glomerulonephritis, renal vasculitis, ureteral obstruction, genetic alterations, autoimmune diseases (1) and drugs (3,4). In general, diabetes causes glomerular hypertension by reducing the afferent arteriolar resistance while stimulating the efferent arterioles (2). Thus, elevated glomerular capillary pressure is one of the major factors in progressive renal sclerosis (5). Diabetes and hypertension gradually lead to glomerular expansion, which causes endothelial dysfunction and haemodynamic changes: loss of the glomerular basement membrane electric charge and its thickening, a decreased number of podocytes, foot-process effacement and mesangial distension have been shown to underlie the initial glomerular injury, which probably leads to glomerulosclerosis. (1). The reaction of renal tissue to damage resembles the common wound-healing response that occurs in other tissues. However, the repair and recovery of tissue function does not always happen, so why do some wounds heal and others progress to fibrosis? The answer is difficult because there are a variety of factors that influence the response to injury (6). The glomerulus is a structure with multiple interactions of endothelial, mesangial and epithelial cells that form the filtering capillary loops (5). Progression of CKD is evidenced by the loss of renal cells and their replacement by extracellular matrix (ECM) (5,7) in glomeruli and interstitium. Chronic glomerulonephritis, tubulointerstitial disease, hypertension, or diabetic nephropathy (8), occurring independently of the associated disease, arise as a consequence of increased synthesis/reduced degradation of ECM (5,7,9). The pathogenesis of glomerulosclerosis has strong similarities to the pathogenesis of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. In general, glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis are the result of an imbalance between the excessive synthesis and decreased breakdown of the ECM, which may result from a normal wound-healing response becoming deregulated, with an uncontrolled inflammatory response and myofibroblast proliferation (10). In this sense matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors are determinants of ECM accumulation (9). In addition, Hewitson suggests that fibrosis may also result from a collapse of the renal parenchyma (6). The end-stage of renal disease is manifested by the presence of glomerulosclerosis, vascular sclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Indeed, glomerulosclerosis is initially attributable to the disproportionate production of ground substance proteins by mesangial cells, associated with a reduction in the extracellular proteolytic activity generated by these cells (2). In this sense, the excessive glomerular production of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, the key cytokine in the development of glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis (11), stimulates mesangial cells (2,12), and is probably the most potent inducer of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (13). Activation of TGFβ results in a self-maintaining cycle of matrix deposition, through an increase in protein synthesis and a decrease in matrix protein degradation, resulting in persistent tissue injury (11,14). The diminution of this cytokine bioactivity reduces ECM deposition and the development of fibrosis in experimental renal injury (11). On the other hand, an increase in oxidative stress has been associated with increased mesangial expression of TGFβ (2) and also stimulation by angiotensin II (Ang II) (15). Endothelial and mesangial oxidant stress related to diabetes and systemic hypertension may also interfere with the production of glomerular nitric oxide, possibly reducing the activity of nitric oxide and thus impairing its protective effect in the process of glomerulosclerosis (2). However, there are additional non-haemodynamic factors, such as growth factors, proto-oncogenes, infiltrating macrophages, proteinuria, reactive oxygen species, hyperlipidaemia and vasoactive substances, such as Ang II and endothelin, that contribute to renal sclerosis. Nevertheless the activity of these factors probably depends on the type of initial damage, the age of the individual when the injury occurs, and complex genetic factors, all of which influence the process of sclerosis (5). Thus, renal fibrosis can also be considered as tubulointerstitial fibrosis, since this process features tubular destruction. Curiously glomerulosclerosis, despite being a disease with its own entity, causes tubulointerstitial fibrosis by inducing tubular destruction. Although it is assumed that tubulointerstitial fibrosis accelerates the degeneration of injured nephrons and these may also interfere with neighbouring healthy tubules, contributing to the progression of kidney fibrosis (16). Existing knowledge about the progression of renal fibrosis is extraordinarily complex and therefore it is difficult to prevent or even eliminate renal fibrosis. Nevertheless, as referred to by Fogo, this is theoretically possible (5). There is great interest in uncovering the processes and underlying factors that lead to renal fibrosis in order to prevent or reverse renal fibrosis. (17). However, it is uncertain whether the elimination of fibrosis will in itself be sufficient to improve renal function, while beyond this, it is also necessary to eliminate inflammation and fibrogenesis, followed by the regeneration and reconstruction of tissue (6). Kaissling and colleagues suggest that renal fibrosis may have a curative component or, on the other hand, that fibrotic tissue supports the survival of healthy and partially injured nephrons (16).

Impact of Renal Fibrosis on Human Health

In recent years, the incidence of CKD has grown in a frightening way. If this tendency persists, even wealthier countries will not be able to come up with sufficient resources to adequately treat this disease (18). Although it is recognized that the kidney has a capacity for regeneration after acute injury, regeneration and recovery, following chronic injury this is much more difficult. Thus this process is often irreversible, leading to end-stage renal collapse, a situation that requires dialysis or renal transplantation (6). In general, between 30-40% of individuals develop considerable kidney failure 10-15 years after the diagnosis of progressive nephropathy (19). It is estimated that currently between 1 and 2 million people are being treated with renal replacement therapy (19-21), which primarily involves kidney transplantation and haemodialysis. Over 90% of these patients live in developed countries, although the availability of renal replacement therapy in developing countries is limited, and insignificant or non-existent in underdeveloped countries. Given the fact that renal replacement therapy represents a high cost burden on national health budgets, this prevents all patients from being given access to this type of treatment (19). The latest estimate, based on results from the US Census Bureau predicted that by the year 2015 the number of cases on renal replacement therapy will be >595,000 (22). The public cost necessary to care for these patients will be considerably greater than it was in 2010 ($28 billion per year), regardless of the exact number of cases (18,22). If these numbers were to be estimated for the entire world’s population, the total number of individuals with CKD could be estimated to be in the hundreds of millions.

Humans and animals develop glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy and reduction in glomerular filtration rate with increasing age (23). In humans with CKD, the development of glomerulosclerosis is evidenced by the progressive involvement of segments within individual glomeruli, a decrease in the total number of glomeruli and by the simplification and elimination of tubular structures (15). The presence of fibrosis in CKD is strongly related to the future manifestation of renal failure and has thus been related with poor long-term prognosis (24). Renal fibrosis is one of the consequences of kidney injury and is associated with renal dysfunction that may culminate in renal collapse (25,26). Renal fibrosis, particularly associated with glomerulosclerosis and renal interstitial fibrosis (5,10,27,28) that is characterised by tubular atrophy, tubular dilatation, increased fibrogenesis (29) and deposition of collagen and ECM (15), can progress in humans as a consequence of chronic infection, obstruction of the ureters, hypertension, diabetic nephropathy and chronic exposure to heavy metals (25).

Principal Molecules, Cells and Other Factors Involved in the Pathogenesis of Renal Fibrosis

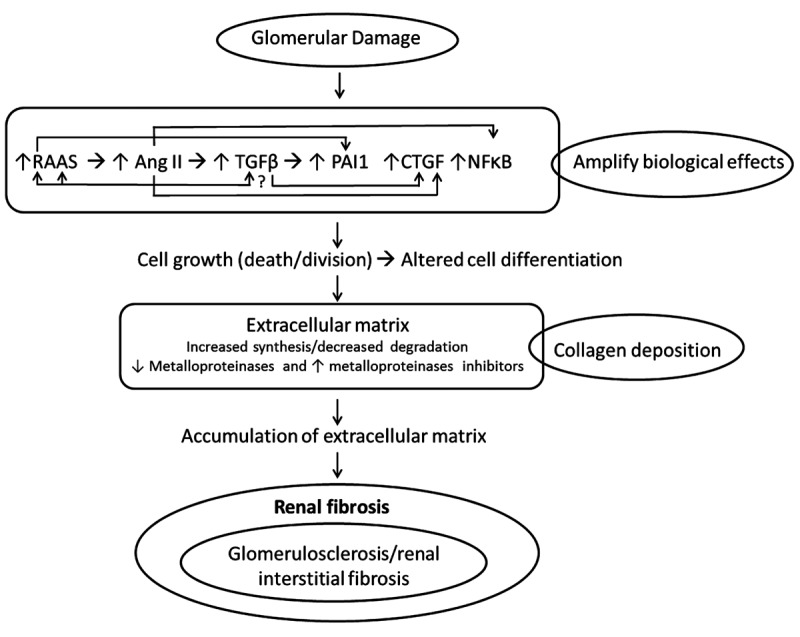

In the following section we describe the main molecules and cells that are associated with progression of renal fibrosis and their activity in the biological process of renal fibrotic development, such as Ang II, TGFβ, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI1), nuclear factor-ĸB (NFĸB), fibroblasts, and proteins (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Glomerular injury can be associated with different causes, leading to endothelial dysfunction and haemodynamic changes. Activation and amplification of many biological effects particularly with production of angiotensin II (Ang II) that up-regulates the expression of other factors, such as transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI1) and nuclear factor ĸB (NFĸB), leading to initial recruitment of neutrophils which is substituted by macrophages and T-lymphocytes, triggering an immune response, causing interstitial nephritis. Tubular cells respond to this inflammatory process by forming a lesion of the basal membrane and by epithelial–mesenchymal transition transformed into interstitial fibroblasts. The formed fibroblasts produce collagen, and result in an imbalance between excessive synthesis and decreased breakdown of the extracellular matrix, which in turn damages the blood vessels and the kidney tubules, with the possibility of forming of a cellular scar and consequently renal fibrosis. RAAS: Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system.

Angiotensin II

All the components of the renin–angiotensin system (including enzymes and receptors) are present in the kidney, and renal Ang II is approximately one thousand-fold greater than the circulating concentrations of Ang II (15). Therefore, increased levels of Ang II modulate fibrosis by the direct effects on the matrix and by up-regulating the expression of other factors, such as TGFβ (5,14), platelet-derived growth factor (5) (which plays a crucial role in the development of mesangial proliferation) (10), CTGF (30), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase activity (2), PAI1 (19), tumour necrosis factor-α, osteopontin, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and NFĸB (NFĸB activation is also strongly associated with an increase in renal fibrosis) (15,31). Ang II also induces oxidative stress. It is believed that most of these negative effects of Ang II are mediated by the Ang II type-1 (AT1) receptor. These factors and the vasoactive compounds involved in the progression of renal fibrosis have been studied in various models of renal diseases (15).

Cell growth after injury is frequently followed by increased apoptosis. Apoptosis may be induced by Ang II and this effect is mediated by the Ang II type-2 (AT2) receptor, showing a possible role for AT2 receptors in the regression of renal fibrosis. This is demonstrated by the activity of the AT2 receptor in the reduction of vascular lesions after damage. In addition, regression of glomerulosclerosis can be achieved by angiotensin inhibition in animal studies, however, this can become more effective when used in combination with an aldosterone antagonism (5) or with TGFβ blockers (20). Renin and aldosterone appear to have fibrogenic effects regardless of Ang II activity, however, it is not known if aldosterone and renin up-regulate TGFβ expression (32), or whether they may be intimately connected with TGFβ production and accumulation of fibrotic matrix.

Transforming Growth Factor β

The accumulation of ECM proteins, which is associated with the progression of glomerulosclerosis/renal interstitial fibrosis and tissue inflammation, seems to be related mainly with the activity of Ang II and TGFβ (20,32,33). TGFβ is secreted in an inactive (latent) form that requires processing before it can exert its effect and latent TGFβ is stored on the surface of cells and the ECM, where it is transformed to active TGFβ (15). Along these lines, Kagami et al. showed that Ang II induces ECM synthesis and that these effects are mediated directly by Ang II induction of the active form of TGFβ (12), indicating that TGFβ contributes to renal fibrosis (2,12,20,31,32). In mammals there are three TGFβ isoforms, however, the form most associated with renal fibrosis is TGFβ1 (34). TGFβ1 is extensively expressed in all cells of the kidney, particularly in glomeruli, where the levels are several times those in the kidney as a whole (20), or expressed by macrophages that invade the kidney (15). TGFβ plays a pivotal role in renal fibrogenesis (7,11,20,35), indeed the kidney is particularly susceptible to the overexpression of TGFβ (32).

TGFβ simultaneously regulates cellular proliferation, differentiation and migration, modulation of the immune response (7), fibroblast proliferation (15), stimulation of oxidative stress (increasing NADPH oxidase activity in mesangial cells) (2), synthesis of ECM, inhibits the activities of proteases that degrade the matrix, and increases the expression of cell-surface integrins that interact with matrix components, causing an extremely high deposition of ECM (32). In this sense, TGFβ induces ECM by stimulating the production of matrix proteins, reducing the production of ECM-degrading proteinases and up-regulating the production of proteinase inhibitors, and induces glomerular mesangial and epithelial cells (in vitro) to produce collagens, fibronectin, proteoglycans (20), laminin (2) and endothelin (15). Another important factor is the ability of TGFβ to stimulate its own synthesis and activation, resulting in a self-sustaining autocrine loop (2). On the other hand, TGFβ also contributes to ECM through the up-regulation of PAI1 (5,32) and increased renin release (32) in isolated glomeruli, reducing the activity of matrix-degrading metalloproteinase (20). This alteration to matrix degradation is also associated with a raised expression of CTGF (2).

Connective Tissue Growth Factor

Yang et al. demonstrated that Ang II directly induces CTGF, as well as collagen I. Ang II was found to induce CTGF expression through a TGFβ1-independent SMAD signalling pathway via the AT1-extracellular signal-regulated kinase/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway to induce renal fibrosis in tubular epithelial cells (30). On the other hand, induction of CTGF by TGFβ1 is markedly inhibited by SMAD7 overexpression (30,36). In another study, in vivo results showed that Ang II directly activates the SMAD pathway in the vessel wall and regulates numerous SMAD-dependent proteins implicated in vascular fibrosis, by a direct TGFβ independent mechanism (37). This demonstrates the crucial function of SMAD signalling in the Ang II-mediated fibrotic process (30). The RAS/MEK/ ERK1/2 signaling pathway is also required for the stimulation of CTGF by TGFβ1 in human proximal tubular epithelial cells, and among the RAS isoforms that are expressed in human kidney cells, NRAS but not KRAS or HRAS were required for the induction of CTGF by TGFβ1 (36). CTGF also appears to be correlated with the degree of tubulointerstitial fibrosis in experimental and human renal fibrosis studies (11). Indeed, CTGF is most abundant in the kidney compared to other tissues, and is an important mediator of renal fibrosis. In a way, there is real potential for CTGF to become a therapeutic target for the treatment of renal fibrosis. CTGF and TGFβ act jointly to promote chronic fibrosis (11,36).

Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1

PAI1 is another mediator that is associated with increased renal fibrosis (19), by stimulation of fibronectin and type III collagen (15). Ang II may also promote PAI1 directly, both in vitro and in vivo (5), which may lead to an accumulation of ECM by reducing the activities of plasmin in eliminating the matrix and stimulating collagenases (32). This shows that the Ang II blockade is extremely important in combatting the evolution of renal fibrosis.

Nuclear Factor-ĸB

NFĸB has a role in the transcriptional regulation of a quantity of genes in different tissues, namely the renal cells (38). NFĸB is located in the cell cytoplasm in an inactive form, linked to an inhibitor, the activated form of NFĸB is a homodimer or heterodimer, structured by two proteins that are part of the NFĸB family. In this sense, transcription factors of the NFĸB family can stimulate cells, directly or indirectly, triggering tissue fibrosis (15). Ang II can be activated by NFĸB through both the AT1 and AT2 receptors. The NFĸB family of transcription factors have several potential associations, it is probable that different NFĸB isotypes are stimulated by Ang II at different phases in the progression of renal disease (31). The tissue enzyme transglutaminase (protein expressed by kidney tubular epithelial cells) is an activator of latent TGFβ1 and the activating of transglutaminase is regulated by NFĸB, consequently this fact appears to be associated with an increase of renal fibrosis. The increased expression of a-smooth muscle actin promotes the kidney fibroblasts to achieve a myofibroblastic phenotype (15). It appears that NFĸB may be associated with an increase in α-smooth muscle actin expression during liver fibrosis (39). As mentioned above, Ang II can promote NFĸB activation, activating tumour necrosis factor-α synthesis; this in turn can additionally activate NFĸB. A 40% reduction in tumour necrosis factor-α mRNA expression was verified with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in rats with kidney disease, perhaps due to the weakening of a group of NFĸB homodimers or heterodimers (31). Therefore, the progression of renal fibrosis might be treated or improved by inhibition of NFĸB (15,38,40).

Fibroblasts

The progression of renal fibrosis is a complex process, since many factors and cells are involved, especially mesenchymal cells (6). Epithelial–mesenchymal transition, a process by which differentiated epithelial cells give rise to the matrix-producing fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, is increasingly documented as an integral part of tissue fibrogenesis after renal injury (13,35,41). In this sense, tubular epithelial cells are also important in the pathogenesis of tubulointerstitial fibrosis (29). Thus, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, such as occurs in common glomerular diseases, could be a primary pathway leading to podocyte dysfunction, proteinuria, and glomerulosclerosis (13). Fibroblasts are mesenchymal cells involved in the progression of renal disease. Fibroblasts of the renal interstitium can play a contractile myofibroblastic phenotype and has the ability to originate fibrillar collagen-rich ECM, leading to impaired renal function. The number of fibroblasts increase during renal disease and can be activated by many cytokines, especially TGFβ1 or differentiate into myofibroblasts (34).

Proteins

Another strategy for preventing, or at least slowing, the onset of glomerulosclerosis is a low-protein diet because a high protein intake increases the glomerular filtration rate by reducing afferent arteriolar resistance and consequently increasing glomerular capillary pressure (2). Elevated levels of urinary proteins, which correspond to excess protein passage through the glomerulus, are related to a quicker progression of renal disease (20). Thus, proteinuria is also an important factor of progression in animal and human renal diseases. One of the factors that causes glomerular and tubular changes includes enhanced glomerular capillary pressure by altering glomerular permeability to proteins, allowing proteins to pass across the glomerular filter and reach the lumen of the proximal tubule. Another factor of tubular reabsorption of filtered proteins that contributes to interstitial damage is by activating intracellular events, leading to up-regulation of the genes encoding vasoactive and inflammatory mediators (20).

Animal Models of Renal Fibrosis

Experimental models are widely used to study the mechanisms involved in the progression of renal diseases to renal fibrosis (5,7). Research on natural aging of the rat kidneys indicate that both gender and genetic background influence the rate, as well as the level, of impairment and scarring from renal disease. Normally, age-related renal scarring begins earlier and becomes more severe in male rats than in females, and Sprague-Dawley rats are less resistant than other rat strains. Research into aging in mice suggests that strain and gender also influence the progression of renal disease (23). It is important to emphasize that these changes are clearly different from the compensatory changes that occur after reduction of renal mass (42). To study renal fibrosis, induced models (surgical and chemical), spontaneous models, genetic models and in vitro models (29,43-48) can be used.

Chemical Models of Renal Fibrosis

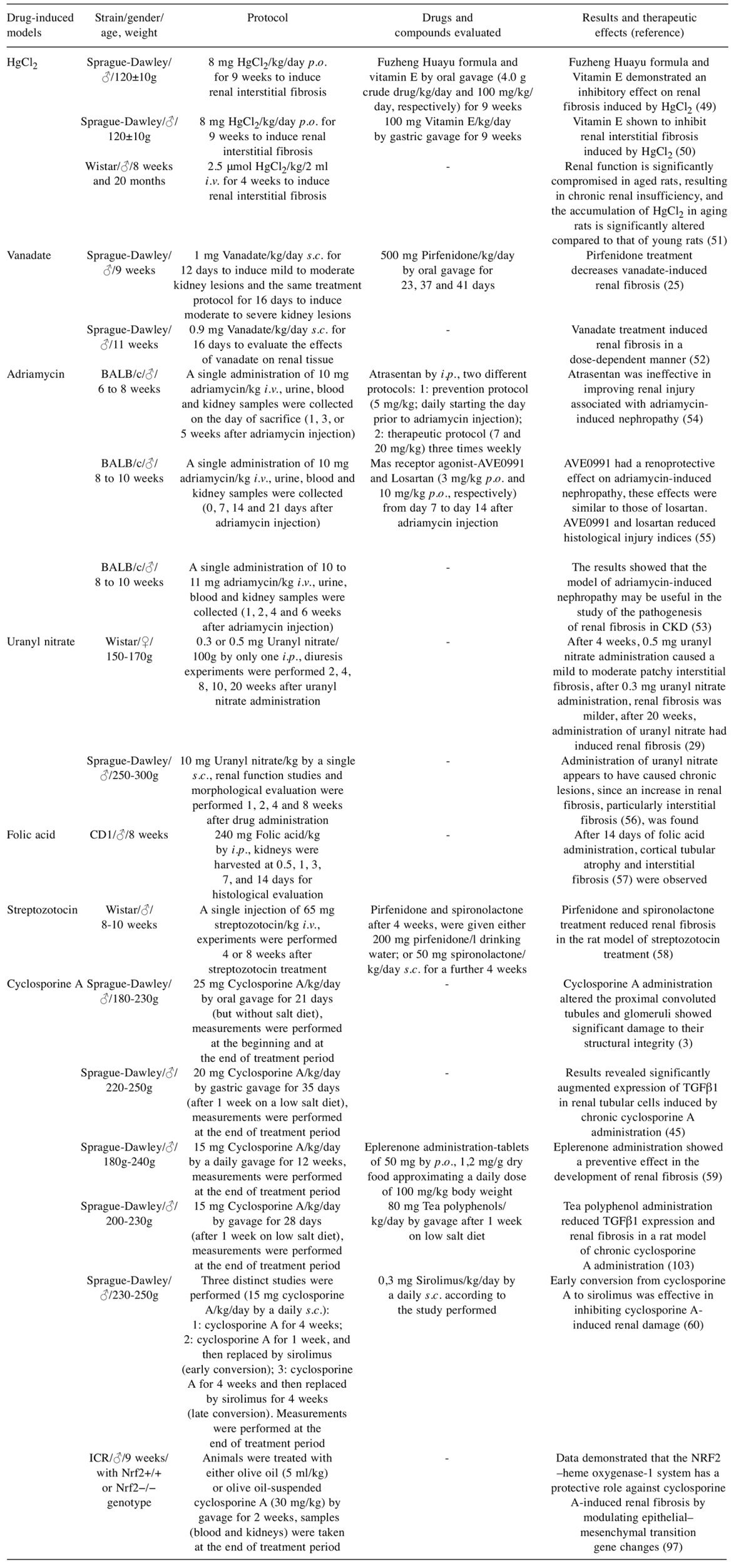

There are several chemical models for studying renal fibrosis, each of which has advantages and disadvantages. We describe each of them below in turn, while in Table I, the practical application of each of these models in the therapeutic evaluation of different drugs is presented.

Table I. Chemical models used for renal fibrosis study - drugs evaluated and their efficacy.

i.v.: Intravenous; s.c.: subcutaneous; i.p.: intraperitoneal; p.o.: per os; HgCl2: mercuric chloride; CKD: chronic kidney disease; TGFβ: transforming growth factor β; NRF2: nuclear factor E2-related factor 2.

Mercuric chloride (HgCl2). HgCl2 per os in Sprague-Dawley rats once a day for 9 weeks led to renal interstitial fibrosis with an increased amount of collagen. The effect of HgCl2 is characterized by the activation of renal fibroblasts, the overproduction and deposition of ECM, increased renal lipid peroxidation (49), elevated NFĸB activity (50), renal necrosis and tubular dysfunction in rats (51).

Vanadate. Vanadate injected subcutaneously in Sprague-Dawley rats aged 11 weeks at a dosage of 0.9 mg/kg per day for 16 days caused inflammation and renal fibrosis. The pathological and biochemical changes were more severe in the kidney tissue. After 2 days, degenerative and necrotic changes of the tubular and glomerular epithelium were identified. After 12 days, cellular proliferation in both the cortex and medulla was significantly greater and there was verifiable renal fibrosis: glomerular tuft, preglomeruli, pretubules and interstitium (cortex and medulla). After 25 days, collagen deposition reached the highest degree in all areas of the kidney. Vanadium-produced fibrosis in tissues is dose-dependent (52).

Adriamycin. Adriamycin is an antineoplastic drug that induces side-effects such as lipid peroxidation in glomerular epithelial cells. Adriamycin induced rat nephropathy with massive proteinuria, tubular basement membrane lesions, probably causing an inflammatory response and interstitial fibrosis (4). Adriamycin administration at a dosage of 10 mg/kg for each mouse by means of a single intravenous tail-vein injection causes proteinuria, glomerular and podocyte injury, followed by tubular atrophy and finally renal fibrosis (53-55). In a study with BALB/c mice, proteinuria was verified on day 5 and at higher levels on day 7; after weeks 1 and 2 glomerular and tubular lesions were observed, and by week 4 these changes were more evident. After week 6, kidney inflammation was observed, as well as severe glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis (53). The adriamycin-induced nephropathy model mimics human disease of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (54) and is also often used to model nephrotic syndrome (23). This model is also excellent for investigating glomerulosclerosis in humans (23).

Uranyl nitrate. Uranyl nitrate administrated by intraperitoneal route (0.3 or 0.5 mg/100g) causes renal fibrotic changes in rats. Uranyl nitrate administration induced mild to moderate patchy interstitial fibrosis after 4 weeks. After 20 weeks, fibrotic areas containing atrophic tubules with a thickened tubular basement membrane and mild lymphocytic infiltration were identified. Uranyl nitrate administration induced renal fibrosis in a dose-dependent manner (29). In another study, uranyl nitrate administration of 10 mg/kg in rats for a period of 2 months appeared to cause chronic injuries, as demonstrated by increased interstitial fibrosis, atrophic proximal tubules and mononuclear cell infiltrates. These authors suggest that the administration of uranyl nitrate in rats induced renal failure with a slow recovery phase and long-term pathological lesions (56). Uranyl nitrate appears to be an optimal model of interstitial fibrosis and is useful for investigating molecular mediators of kidney damage (29).

Folic acid. Folic acid administered via the intraperitoneal route (240 mg/kg) in mice induced the rapid appearance of folic acid crystals in tubules, followed by severe nephrotoxicity, between 1-14 days of the administration period. By 28-42 days, these animals developed patchy interstitial fibrosis. Severe damage induced by folic acid is associated with a direct toxic effect on tubular epithelial cells and by crystal obstruction of individual tubules. However, the co-administration of NaHCO3 and folic acid provokes urine alkalinisation, reducing crystal formation (23,57). The folic acid interstitial fibrosis model, compared to the unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) model, has the advantage of enabling assessment of renal function as a measure of CKD. On the other hand, this model has the limitation of being somewhat variable and the possibility exists that fibrosis in some mice will regress spontaneously after 42 days. This model is good for studying interstitial fibrosis (23).

Streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Streptozotocin administration (65 mg/kg i.v.) in rats increases blood glucose concentration. After 4 or 8 weeks of streptozotocin administration, animals showed collagen deposition in the kidneys, elevated renal plasma fibronectin concentrations (58) and elevated plasma levels of TGFβ, up to four times the normal levels (14). This model can be considered as a renal fibrosis model because sometimes, after the onset of diabetes, renal fibrosis may occur (58).

Cyclosporine A. Cyclosporine A, a primary calcineurin inhibitor, is used clinically as an immunosuppressive agent to enhance the efficacy of organ transplantation. However, prolonged use of cyclosporine A can induce renal fibrosis. Thus, its clinical use is in part limited by its nephrotoxicity effect (3,59). The cyclosporine A model is good for studying interstitial fibrosis (23). However, this model has some disadvantages: high cost, liver toxicity, extensive trial period (4) and the concentrations of cyclosporine A that are commonly used in animal studies are much higher than those used in clinical practice (60).

Physical Models - Radiation Nephropathy

Radiation nephropathy can be induced by a local dose(10 Gy), with shielding of the gastrointestinal tract and without systemic toxicities. Radiation nephropathy leads to the development of endothelial injury and chronic progressive secondary sclerosis with proportional tubulointerstitial fibrosis (23). In Sprague-Dawley rats, radiation (12 Gy) induces an initial decline in glomerular filtration rate and at a later stage, the damage involves complex interactions between glomerular, tubular and interstitial cells, which may culminate in interstitial fibrosis with mild interstitial inflammation. In addition to the likely involvement of TGFβ and PAI1, Ang II is certainly the principal mediator of this process. The results of this study showed that sulodexide (15 mg/kg/day by subcutaneous injection, 6 days/week for 4, 8 and 12 weeks) is effective in reducing the early, but not late, indicators of radiation nephropathy and has no influence on renal damage, despite sulodexide considerably diminishing TGFβ activation (61).

Surgical Models to Induce Renal Fibrosis

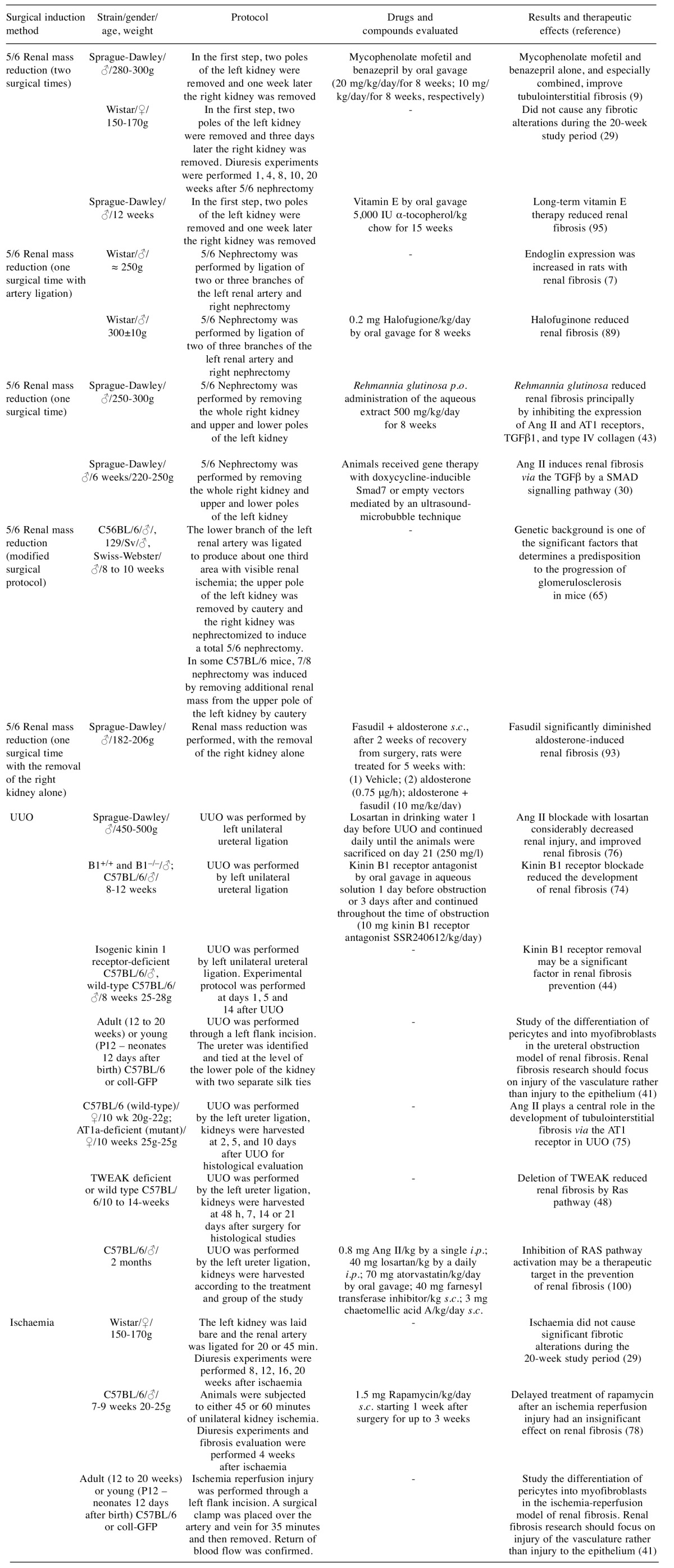

There are three main surgical models to study renal fibrosis, each of which has its advantages and disadvantages. We describe each of them below, and Table II shows the practical application of each of these models in the therapeutic evaluation of different drugs.

Table II. Surgical models used for renal fibrosis study – drugs evaluated and their efficacy.

s.c.: Subcutaneous; i.p.: intraperitoneal; p.o.: per os; TGFβ: transforming growth factor-β; TWEAK: tumour necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis; Ang II: angiotensin II; AT1: angiotensin II type-1; UUO: unilateral ureteral obstruction; coll-GFP: collagen type I-α 1 transcript.

5/6 Renal mass reduction. Over the last 50 years, models using animals that have undergone surgical renal reduction have been used to study progressive renal disorders (17,62). The remnant kidney model of progressive renal disease has been used in different rat and mouse strains to study the pathogenesis of glomerulosclerosis. The 5/6 renal mass reduction model in rats is frequently studied to evaluate alterations in the progression of chronic kidney failure, namely renal fibrosis (5,7,63). A study conducted by Hostetter and colleagues highlighted the action of glomerular hyperfiltration in the development of lesions in remnant glomeruli in rats (64). However, Ma and Fogo, in a study that used the remnant kidney model, recorded small glomerular changes in C57BL/6 mice. On the other hand, in 129/Sv and Swiss-Webster strains, mice were observed to have significant glomerular sclerosis, so to some extent these results demonstrate the effect of genetic background on renal response to renal reduction (65). Sensitivity to the development of glomerulosclerosis and hypertension in 129/Sv and C57BL/6 strains may be predisposed by renin gene polymorphisms. Mice with two renin genes have 10-times greater renin activity in their plasma compared with mice with one renin gene. Because of this increased renin activity in 129/Sv mice, they exhibit a greater predisposition for developing hypertension and glomerulosclerosis (66). Although research studies focus on the various processes of kidney function, clinical studies have also established that the development of renal failure correlates more with renal interstitial fibrosis than with glomerular injury (17).

In the 5/6 renal mass reduction animal model, a renal mass reduction of >85% is required to simulate the decrease in the number of nephrons that occurs with CKD, which makes this model an excellent model for studying the mechanisms involved in compensatory adaptations to nephron loss. The 5/6 renal mass reduction model is achieved by unilateral nephrectomy, followed by the removal of two-thirds of the remaining kidney (67,68). For the study of renal disease, this can be performed in one of two ways: a) unilateral nephrectomy plus polectomy of the remnant kidney, resulting in approximately 5/6 renal mass reduction; and b) unilateral nephrectomy plus complete ligation of two branches of the contralateral renal artery, resulting in infarction of approximately 2/3 of the remnant kidney, which produces an overall 5/6 renal mass nullification (1). In the 5/6 renal mass reduction model, the remaining nephrons increase their filtration rate (64) to preserve the excretory function; renal dysfunction occurs when the remaining nephrons are unable to perform this excretory function (1). Over time, these animals develop a syndrome of systemic and glomerular hypertension (68), proteinuria (64) and matrix expansion (5), and by 12 weeks present progressive glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis in the originally healthy remnant nephrons (23,62,68). In this model, the alterations to the matrix metabolic enzymes in the remnant kidney strengthen the idea that an imbalance of matrix generation/degradation may contribute to the development of renal damage and renal fibrosis following 5/6 renal mass ablation (9). Regardless of aetiology, the reduction in functioning renal mass is associated with progressive glomerulosclerosis (67). This fact makes the 5/6 nephrectomy model one of the most often-used in the study of glomerulosclerosis. However, this model is limited due to the difficulty of performing surgery, the high mortality rate and the sudden loss of a large amount of renal tissue that occurs very rarely in human disease, where loss of functional renal tissue typically occurs more gradually.

As a result of the renal mass reduction, the number of nephrons suddenly decreases and the remaining nephrons begin to develop renal damage, which depends on: the surgical method used; the amount of tissue removed; the strain and sex of the animal (67); and the experimental technique (1). Fleck and colleagues demonstrated that male rats are more resistant to 5/6 renal mass ablation than female rats, and suggest higher resistance in Sprague-Dawley rats to 5/6 renal mass ablation compared with Wistar rats, indicating that strain and gender influence the progression of renal disease in the experimental model of a 5/6 nephrectomy (69).

Unilateral ureteral obstruction. Obstructive uropathy is the main cause of end-stage renal disease in children of the United States, being one of the main reasons for paediatric kidney transplants (70). Urinary pathway obstruction, which may result either from the blockage of one or both ureters, provokes the progressive damage of renal structures, which leads to chronic renal dysfunction. Ureteral obstruction leads to kidney enlargement, caused by urine collecting in the renal pelvis or calyces, which causes hydronephrosis (1,71). This situation therefore causes renal dysfunction by impeding the normal flow of urine through the renal pelvis, ureters, bladder and urethra (1). In rodents, UUO can be considered the most widely used model to study the mechanisms of non-immunological tubulointerstitial fibrosis (72). The surgical technique applied to achieve this animal model is relatively simple, if performed as a single process in an adult rats (17) and mice (31), with the ligation of the ureter being most frequentlyused technique [see Chevalier et al. (17)]. In general, the alterations caused by this model are established within 7 days in mice and 2-3 weeks in rats (4).

UUO is the most widely used interstitial fibrosis model, due to the rapid tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis development and matrix deposition (73). The UUO animal model and human obstructive nephropathies have very similar aetiology. However, this absolute obstruction very rarely occurs in humans, but due to its accelerated time course, this model reproduces a fibrotic sequence of events that is almost identical to that found in humans (1,31). In UUO, the first alterations observed in the kidneys are haemodynamic, mainly triggered by the increased activity of the vasoconstrictor systems, namely the renin–angiotensin system (72). After complete UUO in the obstructed kidney, there is a progressive decline in renal blood flow, glomerular filtration rate and rapid damage of the renal parenchyma. Most of the renal cellular alterations occur after 2-3 weeks (17), namely an increase in intratubular pressure, and consequently an extension of the tubule walls (31), epithelial tubular cell damage (72) and subsequently a significant increase in renal fibrosis indicators as inflammation mediated by macrophages (44,74) and myofibroblasts (72). These cells produce cytokines and growth factors that trigger an inflammatory process in the kidney after UUO, inducing ECM deposition and cell apoptosis. Furthermore, oxidative stress and the renin–Ang II system play an important role in the overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the UUO. In this sense, it is fully established that TGFβ and NFĸB play a central role in stimulating ECM production and in the inflammatory process after UUO, respectively (72). The pro-inflammatory kinin B1 receptor contributes to the development of UUO-induced renal inflammation and consequently renal fibrosis. In this way, Klein and colleagues (2009) showed that kinin B1 receptor blockade significantly reduced the progression of evident renal fibrosis in the UUO animal model. It seems that this effect was in part provoked by a mechanism related with the inhibition of CTGF and chemokine expression by resident renal cells and without altering TGFβ expression (74). Nevertheless, Wang and colleagues demonstrated that kinin B1 receptor deletion reduced renal fibrosis while improving expression of anti-inflammatory factors (heme oxygenase-1 and interleukin-10) and reducing that of the pro-inflammatory factors (TGFβ and interleukin-6) (44). These results demonstrate that B1 receptor blockade reduces renal fibrosis by modifying the expression of the immune components, however certain effects/processes involved remain to be determined.

An imbalance between vasoconstricting and vasodilating substances may demonstrate haemodynamic changes observed in the UUO model. This leads to the activation of the plasma and renal renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, triggering subsequent pathological alterations through the activation of TGFβ and NFĸB (75), the infiltration of immune cells, fibrosis and renal hypoperfusion (31), and the overexpression of CTGF (74). Indeed, as demonstrated in several studies, renal Ang II is the crucial mediator of the renal response to UUO, including inflammation, apoptosis, interstitial fibrosis (17,31,75,76), and increased fibroblast expression (76). In a study by Kellner and colleagues, the losartan angiotensin receptor antagonist considerably reduced renal injury in the UUO model, improving apoptosis, renal fibrosis, fibroblast and macrophage expression infiltration, and thus demonstrating the effectiveness of this type of treatment. About 50% of the renal alterations were not affected by this treatment, indicating that there are other factors in the development of renal injury in UUO. However, these facts suggest that Ang II is responsible for around 50% of the renal fibrotic response in UUO (76). Total UUO is a pathological condition that causes tubular atrophy, proliferation and apoptosis of the epithelial tubular cells, macrophage infiltration, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, interstitial cell infiltration, ECM deposition, collagen I deposition and an accumulation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts (31). Lin and colleagues identified the pericytes and fibrocytes as two sources of collagen I in the UUO of renal fibrosis (41), also showing that pericytes are the source of myofibroblasts, highlighting the key role that pericytes play in the development of renal fibrosis (41,77). In another study, absence of tumour necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) delayed the accumulation of myofibroblasts and reduced ECM deposition in the UUO mouse model. On the other hand, TWEAK overexpression promoted renal fibrosis in mice without any kidney damage (48). These results showed the fibrotic actions of TWEAK that should be further investigated in order to understand the mechanisms of a chronic persistent kidney injury model such as the UUO model.

However, in this model, the recovery time following the removal of the obstruction is inversely proportional to the duration of the obstruction. On the one hand, in the UUO, one of the first consequences of peritubular capillary destruction, tubular atrophy and progressive renal insufficiency is renal interstitial matrix accumulation. However, on the other hand, renal inflammation leads to glomerular and tubular damage in some nephrons, which in turn leads to the damage of the remaining nephrons, demonstrating that interstitial fibrosis is a secondary expression of the disease (17).

Animal UUO models can be used in research to obtain new therapeutic options for the more effective treatment of renal fibrosis, e.g. mouse models, which have the advantage of genetic manipulation of species (31). This is especially so since this model has a rapid time course (6), does not use exogenous toxins, lacks the ‘uremic’ environment, allows for variations in the severity, timing, and duration of obstruction (17), has good reproducibility, easy performance, availability of the contralateral kidney as a control factor and is specific strain independent (23). However, this model does have some deficiencies, for example, the incapacity to monitor changes in renal function, because the unobstructed contralateral kidney offsets the loss in renal function (6), and as it is realized with acute injury, may not be indicated for the study of all conditions of renal fibrosis (4).

Ischaemia-reperfusion. The ischemia-reperfusion model is performed in rats through median abdominal incision: the left kidney is laid bare and the renal artery is ligated for 20 or 45 min in Wistar rats (29), and in C57BL/6 mice by 45 or 60 min of unilateral kidney ischemia (78). After one day, the right kidney is removed via a dorsal incision to eliminate the compensatory effects of the contralateral kidney. Kidney samples from the rats taken 20 weeks after 20 and 45 min ischaemia did not show significant interstitial fibrosis. Some kidney samples exhibited atrophic tubules and revealed a slightly thickened tubular basement membrane (29). Takada et al. similarly demonstrated that the morphological changes occurring predominantly between 20 and 40 weeks after renal ischaemia are glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis (79). Ischemia duration is also very important since the almost-complete recovery of renal function and morphology has been observed in rats 4 weeks after 30 min ischaemia (80).

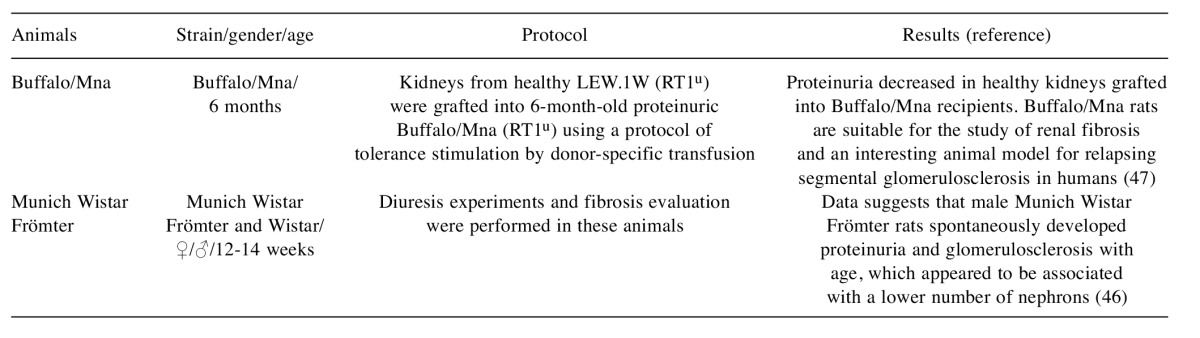

Spontaneous Models of Renal Fibrosis

There are several references in literature indicating that certain mouse and rat strains may be more vulnerable to the development and progression of renal disease and provide the opportunity to investigate new mechanisms and new genes that lead to spontaneous renal fibrosis. Thus, genetic background plays an important role in the response to renal injuries (65,81). Wistar-Kyoto (WKY)/NCrj and ACI/NMs rats are resistant to glomerulosclerosis, and male PVG/c rats are totally resistant to glomerulosclerosis. On the other hand, male Wistar rats are predisposed to the spontaneous development of glomerulosclerosis, and approximately 100% of Buffalo/Mna strain rats spontaneously develop glomerulosclerosis over time (65) (Table III).

Table III. Spontaneous models used for renal fibrosis study.

Buffalo/Mna rats. Between 2 and 4 months of age Buffalo/Mna rats spontaneously develop podocyte alterations, proteinuria, but without verification of sclerotic glomeruli. At the age of 6 months, these animals had a few sclerotic glomeruli in all sections of kidney examined. At 22 months of age, about 37.8-52.1% of the glomeruli became sclerotic (82). These rats are suitable for use as animal models to investigate renal fibrosis in humans (23).

Munich. Munich Wistar Frömter rats have a congenital deficit with approximately 30-50% fewer nephrons than normal, and structural changes (sclerosis) that develop spontaneously with age (23). By the age of 10 weeks, these rats develop proteinuria, and by week 35 the kidneys demonstrate marked glomerulosclerosis (83). In these animals, aging is also associated with a progressive increase in blood pressure. This situation is more noticeable in females than in males. However, males and females have a similar glomeruli number per kidney. This gender-related difference can be explained by the higher single nephron filtration rate and glomerular volume verified in males when compared to females (46,83). These rats are animal models to investigate renal fibrosis in humans; they allow us to study the progression of renal disease associated with a reduction in the number of nephrons (23,46).

Genetically Modified Models of Renal Fibrosis

Renal fibrosis is much more difficult to induce in mice than in rats, since mice demonstrate greater resistance to experimental techniques. Thus, it is important to develop a mouse model in which renal fibrosis can be induced by a simple and unique procedure (84). Here, we describe four animals genetically modified for this purpose (Table IV).

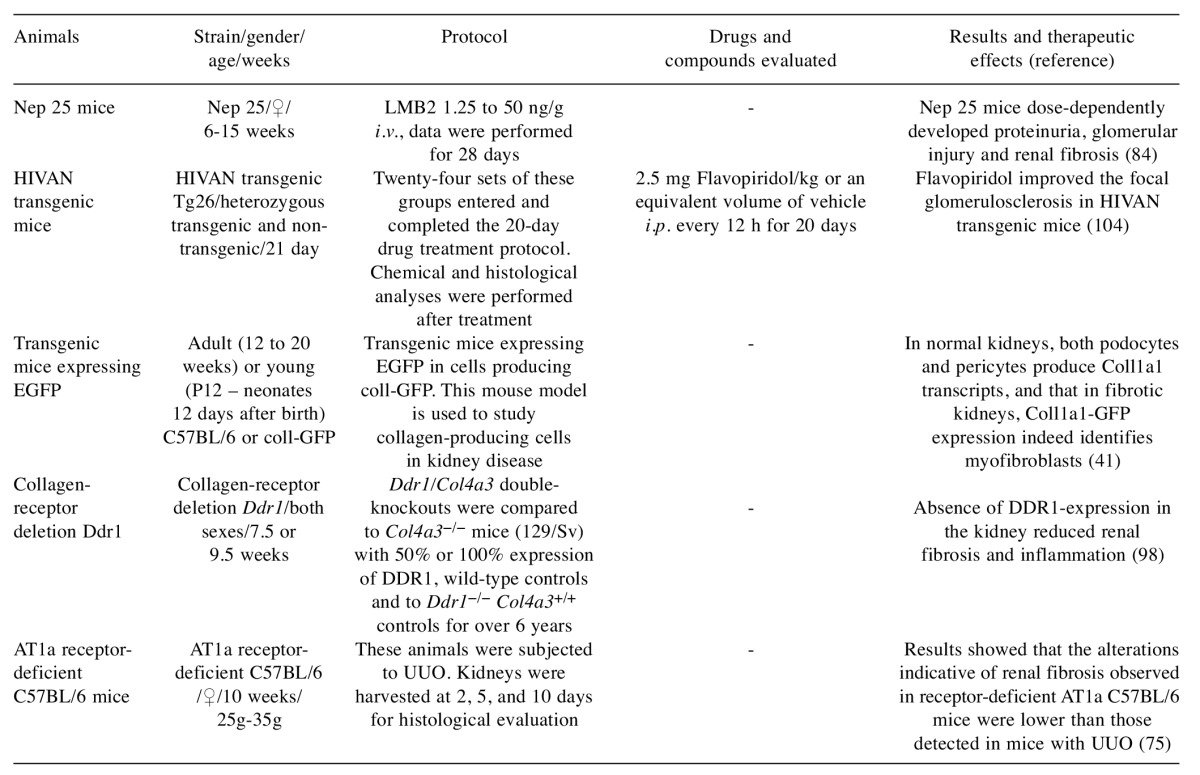

Table IV. Genetic models used for renal fibrosis study – drugs evaluated and their efficacy.

i.v.: Intravenous; i.p.: intraperitoneal; Nep25: transgenic mouse strain; HIVAN: HIV-associated nephropathy; coll-GFP: collagen type I-α1 transcript; DDR1: discoidin domain receptor 1; EGFP: enhanced green fluorescent protein; UUO: unilateral ureteral obstruction; AT1: angiotensin II type-1.

Transgenic mouse strain (Nep25). Nep 25 mice exhibit genetically modified podocytes expressing a toxin receptor, being selectively diminished by single intravenous injection of anti-Tac (Fv)-PE38 (LMB2), a specific toxin, which led to selective and irreversible damage in the podocytes. Thus, the severity of disease can be controlled by the dose of toxin administered and knowledge of the exact time and location of the onset of the disease. After this injection, transgenic mice dose-dependently developed proteinuria and glomerular damage and subsequently renal fibrosis (84). Renal fibrosis in these transgenic mice and renal human fibrosis have similarities, and they can therefore be used to study podocytopathies (23).

HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) transgenic mouse model. The HIVAN transgenic mouse model was developed using transgenic 26 mice (Tg26) with a defective HIV provirus as the integrated transgene (23,85). HIVAN may be considered a rapidly progressive form of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (86). At 24 days of age, these animals displayed proteinuria and HIV-specific gene expression in the kidneys, and between 2 and 6 months of age a high mortality rate (20%) and slight focal glomerulosclerosis were proven. Moribund animals demonstrate considerable glomerulosclerosis, microcystic tubular alteration and tubular epithelial degeneration, and interstitial nephritis, changes very similar to those found in human HIVAN (23,85). Based on this Tg26 mouse model, a rat HIVAN model has also been developed which shows a more markedly expressed HIV transgene, however without glomerular collapse (23).

Coll-green fluorescent protein transgenic mice. Transgenic mice were generated expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in cells producing the collagen type I-α 1 (Coll1a1) transcript (coll-GFP mice). Collagen I-α1 is the most abundant protein in collagen-I fibrils. These mice express a single copy of 3.5 kb of the 5’ Coll1a1 promoter, 0.5 kb of the 3’ uncoded region and four upstream enhancers, driving EGFP expression, and have been shown to label collagen-I α1-producing cells with high sensitivity and specificity. This model is used to study collagen-producing cells in renal fibrosis (41).

AT1 receptor-deficient mice. Angiotensin AT1a receptor-deficient C57BL/6 (mutant) mice have a targeted replacement of AT1a loci by the lacZ gene. These animals enable us to clarify the importance of AT1a-mediated signal transduction pathways in the pathophysiology of renal diseases, especially tubulointerstitial injury. Therefore, C57BL/6 (mutant) mice are useful in the study of the specific function of AT1a receptor (87).

In Vitro Models

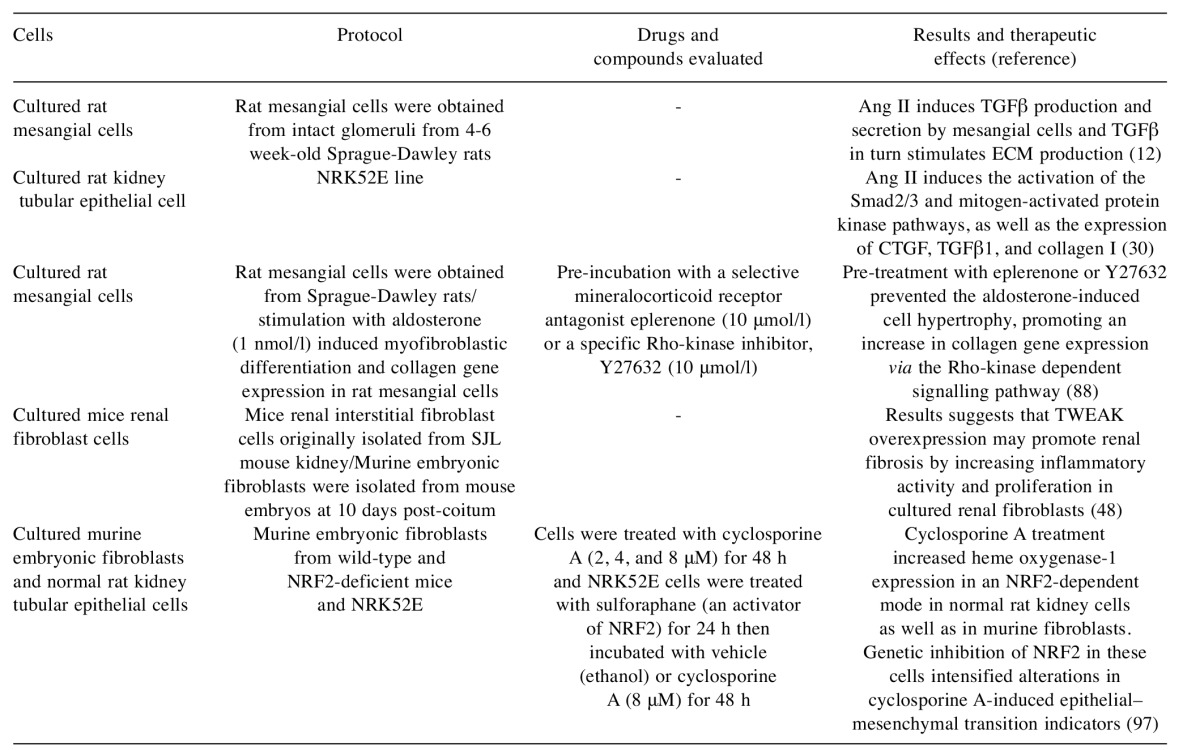

Nearly all intrinsic renal cells have been widely studied to assess specific mechanisms and signal pathways of renal fibrosis development. However, the results are incomplete, usually based on very specific aspects concerning only one cell type and very different from the complexity verified in renal fibrosis responses when studied in animal models (23) (Table V).

Table V. In vitro models used for renal fibrosis study – drugs evaluated and their efficacy.

Ang II: Angiotensin II; TGFβ: transforming growth factor-β; ECM: extracellular matrix; NRK52E: normal rat kidney tubular epithelial cells; CTGF: connective tissue growth factor; TWEAK: tumour necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis; NRF2: nuclear factor E2-related factor 2.

Cultured rat mesangial cells. Rat mesangial cells are used to study the physiopathological processes of renal disease in particular renal fibrosis, for example, the action of Ang II on TGFβ production and secretion by mesangial cells and the potential roles of Rho-kinase in aldosterone-induced mesangial cell hypertrophy (12,88).

Cultured mouse renal fibroblast cells. Mouse renal fibroblast cells are used to study the molecular and cellular mechanisms promoting renal fibrosis. Cultured renal fibroblast cells can be used to evaluate the effect of tumour necrosis factor superfamily cytokines in the induction of the renal fibrosis process. Ucero and colleagues demonstrated that TWEAK induced inflammatory activity and proliferation in renal fibroblast cells, and this action has an RAS-dependent pro-proliferative and NFĸB-dependent proinflammatory effects (48).

Effective Treatments and New Perspectives of Research

A very important factor in the preservation of renal function is the control of hypertension and hyperglycaemia (2). In humans, failure of kidney function caused by fibrosis generally happens many years after the onset of diabetes or recurrent infections. Although it is not possible to reproduce this phase in animal studies, the use of animal models for renal fibrosis allows for the evaluation of drug efficacy in the treatment of renal fibrosis and also the pathogenesis of this disease (25). However, there are few or no drugs with the capacity to prevent the fibrotic process in experimental and human CKD (89), not only in monotherapy but also with a combination of therapies, perhaps because renal fibrosis is a complex process that involves several cell types and mediators (90).

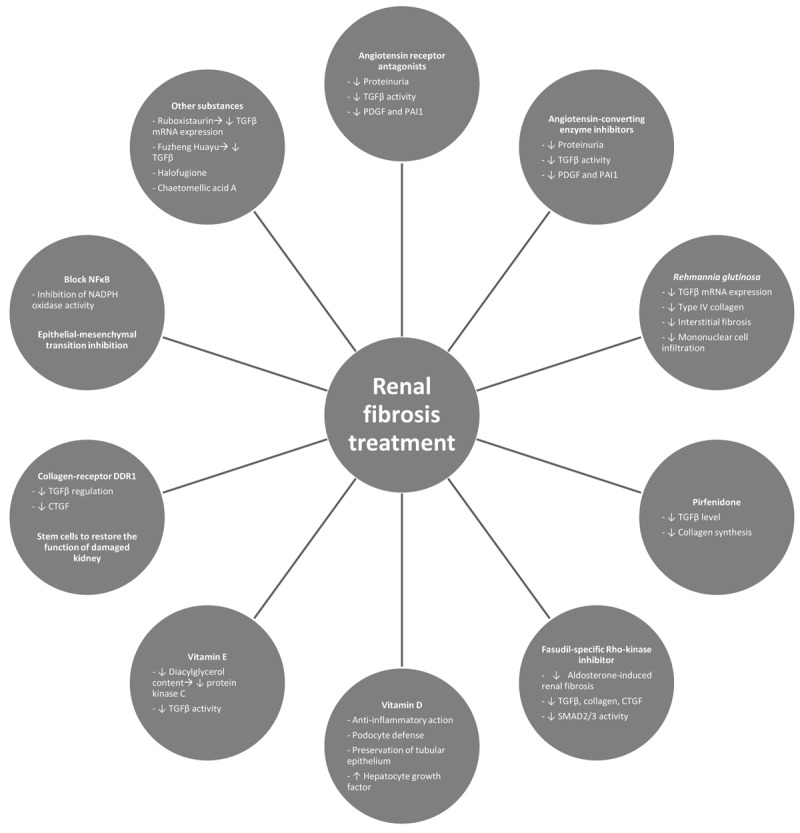

Treatments that target the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibition, carried out with two types of drugs: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor antagonists, are extremely effective in reducing proteinuria, CKD progression and renal fibrosis in humans and experimental models (1,5,12,19). Indeed, Ang II is a principal mediator in the pathogenesis of renal disease (8). The use of higher doses of these two drugs can more effectively reduce fibrosis (32), and the benefits of this treatment are independent of blood pressure reduction (2). One of the factors leading to these effects by the blockage of the renin angiotensin system is indeed the reduction of the activity of TGFβ (14,20) and also platelet-derived growth factors and PAI1 (5). In a study carried out in humans, losartan, an Ang II receptor blocker, diminished PAI1 in cyclosporine-treated renal graft recipients. Ang II blockage and PAI1 diminution may be an important action in preventing renal fibrosis (91). Currently, Ang II inhibition is clinically considered to be the most effective therapeutic intervention for preventing or reducing the development of most renal diseases (17). Although angiotensin–converting enzyme inhibition has widely recognized clinical benefits on the development of renal sclerosis, it is not equally effective at all stages of renal fibrosis, i.e. it is more effective in the earlier stages of sclerosis than in its advanced stages (5) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effective and new treatments of renal fibrosis. PDGF: Platelet-derived growth factors; PAI1: plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; CTGF: connective tissue growth factor; DDR1: discoidin domain receptor 1; TGFβ: transforming growth factor-β; NFĸB: nuclear factor-ĸB; NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; mRNA: messenger ribonucleic acid.

Treatment with Rehmannia glutinosa inhibits the progression of glomerulosclerosis by reducing TGFβ mRNA expression and type IV collagen accumulation and is likely to prevent the presence of interstitial fibrosis and mononuclear cell infiltration (43). Pirfenidone, an anti-fibrotic molecule, attenuates renal fibrosis in the UUO model by reducing the level of TGFβ and the synthesis of collagen in the renal tissue, suggesting that pirfenidone may be applied as a treatment of renal fibrosis progression (92). However, despite the fact that anti-TGFβ therapies are associated with improved renal fibrosis (2,7), it should be cautiously selected for regression of renal fibrosis because TGFβ is involved in the glomerular self-defence system that limits inflammation in renal injuries (20). On the other hand, a combination of TGFβ antibody with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors offers superior nephroprotective effects than single treatments in that it normalizes blood pressure, proteinuria and led to regression of glomerulosclerosis and tubular injuries in rats (20). Blockade of the kinin B1 receptor is another promising antifibrotic therapy for renal fibrosis in animal models of obstructive nephropathy (44,74). In another study, it was verified that the therapeutic combination of mycophenolate mofetil (immunosuppressive agent) and benazapril (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor) was more effective in the treatment of renal fibrosis than mycophenolate mofetil and benazapril alone in 5/6 nephrectomized rats (9). Treatment with fasudil, a specific Rho-kinase inhibitor, significantly improved aldosterone-induced renal fibrosis and increased collagen, TGFβ, and CTGF expression as well as SMAD2/3 activity in the kidneys of rats which had undergone a right uninephrectomy (93). In another study, the effects of aldosterone were diminished by pre-treatment with a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist and Rho-kinase inhibitor (88). This type of study, with a combination of two or more drugs, showed more effective results in several models of renal fibrosis, and should be considered as potential treatments. Nevertheless, further studies in animal models are required to confirm whether TGFβ and aldosterone blockers or other agents are beneficial for combatting the progression of renal fibrosis, and to assess whether these therapies can actually be investigated in human clinical trials because it is evident that Ang II blockade alone is not sufficient for preventing or regressing renal fibrosis.

Yang and colleagues showed that the ability to block SMAD3 but not SMAD2, and to inhibit Ang II-mediated CTGF and fibrotic responses, may also be an alternative therapy for preventing the progression of renal fibrosis (30). It seems possible to inhibit matrix deposition and renal fibrosis within the kidney by blocking CTGF expression without affecting TGFβ expression. Furthermore, CTGF blockade promotes some anti-profibrotic properties similar to TGFβ blockade, however, it probably does not share the immunomodulatory properties of TGFβ (36). In another study, it was demonstrated that CTGF siRNA blocked the epithelial–mesenchymal transition in rat kidney grafts undergoing chronic allograft nephropathy (94). CTGF inhibition may be considered a potential therapy for preventing renal fibrosis.

Active vitamin D and its analogous elements reduce renal fibrosis by attenuating glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis. The various actions of active vitamin D on kidney function, depending on the nature and aetiologies of the CKD animal models, consist of the regulation of the renin–angiotensin system, anti-inflammation, podocyte defence, hepatocyte growth factor induction and preservation of tubular epithelium by blocking epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Supplementary treatment with active vitamin D can thus improve renal function in individuals with CKD (73).

Treatment with vitamin E significantly reduced the degree of kidney structural damage in the 5/6 nephrectomized rats, showing that treatment with vitamin E reduces glomerulosclerosis in 5/6 nephrectomized rats (95). Perhaps this is associated with the fact that vitamin E somewhat attenuates the rise in glomerular and mesangial diacylglycerol content that mediates the overactivation of protein kinase C (primary mediator of renal dysfunction in diabetic rats). Vitamin E treatment also attenuates glomerular and mesangial TGFβ activity. Ruboxistaurin, a drug which inhibits this isoform of protein kinase C, was tested in diabetic rats, and has been observed to reduce the mesangial expression of TGFβ mRNA and to some extent suppress glomerulosclerosis (2). In another study, Wang and colleagues showed that the Fuzheng Huayu formula and vitamin E have an inhibitory effect on renal fibrosis by reversing tubular epithelial–mesenchymal transition in renal interstitial fibrosis induced by HgCl2 in rats. Additionally, the Fuzheng Huayu formula directly reduced TGFβ-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition in human proximal tubular epithelial cells. This action is probably potentiated, at least in part, by reducing SMAD2/3 phosphorylation (49). Indeed, it appears that in rats, vitamin E has a protective effect on HgCl2-induced renal interstitial fibrosis (49,50). However, it is worth noting that a meta-analysis of 136,000 subjects in 19 clinical trials indicated that a high dosage (400 IU/day) of vitamin E supplements increased all-cause mortality in humans, limiting the efficacy of this treatment in humans (96).

Halofuginone, a collagen I inhibitor, showed a beneficial decrease in the progression of renal fibrosis in the experimental model of 5/6 renal mass ablation, and this was independent of blood pressure alterations (89).

The NFĸB family can directly and indirectly stimulate cellular actions leading to tissue fibrosis. Cytokine-medicated counter-regulatory mechanisms that block NFĸB activation might possibly prevent renal disease initiation/progression (15). Other types of treatment may concern the inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity, an important mediator of renal fibrosis. The use of agents with antioxidant properties appears to have benefits in the regression of renal fibrosis in nephropathy rats (2).

Extracellular factors and intracellular mediators that control epithelial–mesenchymal transition have been recognized as a possible alternatives in combat against the progression of renal fibrosis (13). Shin et al. suggest that treatment with small-molecule nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (NRF2)-specific activators might be an alternative therapy for the prevention or regression of the epithelial–mesenchymal transition fibrosis process evidenced by oxidative stress (97).

Collagen-receptor: discoidin domain receptor 1 (DDR1) is involved in the pathogenesis of Alport syndrome, including renal inflammation and fibrosis. The inhibition of this receptor seems to represent a new therapeutic strategy in the progression of renal fibrosis in the future. This nephroprotective effect on the loss of DDR1 may be due to the down-regulation of profibrotic cytokines TGFβ and CTGF (98).

Chaetomellic acid A, a selective inhibitor of HRAS farnesylation (99) tested in mice who had undergone UUO, showed a promising action on the reversal of renal fibrosis (100). In addition, our research team demonstrated that inhibition of RAS activation with chaetomellic acid A may be a future strategy in the prevention of renal fibrosis (101).

Another alternative treatment for renal fibrosis might be the use of stem or progenitor cells to treat or restore the function of the damaged kidney. This type of treatment allows us not only to halt the progression of the disease but also to restore renal function, however, we need to confirm several mechanisms of the stem or progenitor cell action (102).

It is currently thought that cultured cells with features of glomerular epithelial differentiation have an important action on the development of renal damage due to the effects of plasma proteins on podocyte function. In this way, proteins, beyond being a simple indicator of renal damage, can be toxic to the kidney (19).

Through latest-generation confocal and multiphoton microscopy, and with the help of computer programmes, we are able to identify differences within the glomerular network organization that emerge during sclerosis regression, which allows for the identification of changes in cell and gene expression (19). Despite the progress achieved in several studies with different types of treatments and drugs, no drugs presently exist for the effective treatment of renal fibrosis (25).

Conclusion

CKD has many different genetic and environmental causes and several pathological effects such as renal fibrosis, hence this is why it is very important to use different animal models. These models have provided important insight into the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis. The use of appropriate models for the study of renal fibrosis may provide information that provides an understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms of the causes and progression of the disease, as well as potential therapeutic interventions. In particular, the expansion of experimental models for renal fibrosis has allowed the productive investigation of factors associated with cellular and molecular responses to damage caused by renal disease and the fibrotic sequence of events. There is a variety of animal models which display characteristics and aspects of the relevant human renal disease. Among the many animal models used to study renal fibrosis, some are more commonly used than others and therefore there is little information available on the less-studied models. The most commonly used models to investigate renal fibrosis are UUO and 5/6 renal mass reduction, perhaps because they have more advantages and similarities to studies of renal fibrosis in humans, or simply because they have been the most used in recent years. On the other hand, in our research, we found that in many investigations, not all methods and materials are disclosed. For these reasons, many of the renal fibrosis models, especially those that are used less often, are very difficult to reproduce.

The most frequent pathophysiological changes in humans have been successfully reproduced in animal models, which increases our understanding of human pathology and enables us to develop new animal models and also evaluate new therapies. However, no model exactly mimics all the alterations caused by the progression of renal disease in humans such as renal fibrosis, because the factors associated with this disease are not yet completely understood. Due to the different aetiological factors of this disease, it is necessary to evaluate precise experimental data because the analysis of the results obtained in the animal models could lead to wrong conclusions about the pathophysiology of renal fibrosis in humans. Thus, the extrapolation of outcomes from animal models to humans should consider that the mechanisms of fibrosis and efficacy of interventions and treatments differ considerably with different models of renal fibrosis. Perhaps the greatest challenge is to understand how to adapt the experimental innovations to clinical reality. Currently, there are no effective treatments that prevent the progressive destruction of nephrons or avoid the formation of scar tissue. Nevertheless, the potential of the renin–angiotensin system in renal lesions that leads to ECM and sclerosis should be emphasized by the effectiveness of therapies that aim to inhibit its various actions. It is therefore important to improve our knowledge of the cellular and molecular stages of the development of renal fibrosis in order to determine specific markers that will allow for appropriate intervention in the progression of CKD, and perhaps even achieve a regression/ elimination of renal sclerosis.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare that they have no conflict of interests in regard to this study.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a project grant from the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Ministério da Educação, Portugal (grant no. SFRH/PROTEC/67576/2010).

This work was supported by: European Investment Funds by FEDER/COMPETE/POCI– Operacional Competitiveness and Internacionalization Programme, under Project POCI-01-0145-FEDER-016728 and National Funds by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FTC), under the project PTDC/DTP-DES/6077/2014 and by European Investment Funds by FEDER/COMPETE/POCI– Operacional Competitiveness and Internacionalization Programme, under Project POCI-01-0145-FEDER-006958 and National Funds by Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FTC), under the project UID/AGR/04033/2013.

References

- 1.Lopez-Novoa JM, Martinez-Salgado C, Rodriguez-Pena AB, Lopez-Hernandez FJ. Common pathophysiological mechanisms of chronic kidney disease: Therapeutic perspectives. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;128(1):61–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarty MF. Adjuvant strategies for prevention of glomerulosclerosis. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67(6):1277–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chia TY, Sattar MA, Abdullah MH, Ahmad FUD, Ibraheem ZO, Li KJ, Pei YP, Rathore HA, Singh GKC, Abdullah NA, Johns EJ. Cyclosporine A-induced nephrotoxic Sprague-Dawley rats are more susceptable to altered vascular function and haemodynamics. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2012;4(2):431–439. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao J, Wang H, Cao AL, Jiang MQ, Chen X, Peng W. Renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis: A review in animal models. J Integr Nephrol Androl. 2015;2(3):75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fogo AB. Progression and potential regression of glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2001;59(2):804–819. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.059002804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hewitson TD. Renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis: Common but never simple. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296(6):F1239–1244. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90521.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Pena A, Prieto M, Duwel A, Rivas JV, Eleno N, Perez-Barriocanal F, Arevalo M, Smith JD, Vary CP, Bernabeu C, Lopez-Novoa JM. Up-regulation of endoglin, a TGF-beta-binding protein, in rats with experimental renal fibrosis induced by renal mass reduction. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(Suppl 1):34–39. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.suppl_1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu L, Noble NA, Border WA. Therapeutic strategies to halt renal fibrosis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2(2):177–181. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(02)00144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu WH, Tang NN, Zhang QD. Could mycophenolate mofetil combined with benazapril delay tubulointerstitial fibrosis in 5/6 nephrectomized rats. Chin Med J. 2009;122(2):199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.el Nahas AM, Muchaneta-Kubara EC, Essawy M, Soylemezoglu O. Renal fibrosis: Insights into pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta S, Clarkson MR, Duggan J, Brady HR. Connective tissue growth factor: Potential role in glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2000;58(4):1389–1399. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kagami S, Border WA, Miller DE, Noble NA. Angiotensin-II stimulates extracellular-matrix protein-synthesis through induction of transforming growth-factor-beta expression in rat glomerular mesangial cells. J Clin Invest. 1994;93(6):2431–2437. doi: 10.1172/JCI117251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y. New insights into epithelial–mesenchymal transition in kidney fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(2):212–222. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008121226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Branton MH, Kopp JB. TGF-beta and fibrosis. Microbes Infect. 1999;1(15):1349–1365. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klahr S, Morrissey JJ. The role of vasoactive compounds, growth factors and cytokines in the progression of renal disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2000;7:S7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaissling B, Lehir M, Kriz W. Renal epithelial injury and fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832(7):931–939. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chevalier RL, Forbes MS, Thornhill BA. Ureteral obstruction as a model of renal interstitial fibrosis and obstructive nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2009;75(11):1145–1152. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xue JL, Ma JZ, Louis TA, Collins AJ. Forecast of the number of patients with end-stage renal disease in the United States to the year 2010. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(12):2753–2758. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12122753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Remuzzi G, Benigni A, Remuzzi A. Mechanisms of progression and regression of renal lesions of chronic nephropathies and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(2):288–296. doi: 10.1172/JCI27699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gagliardini E, Benigni A. Role of anti-TGF-beta antibodies in the treatment of renal injury. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17(1-2):89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lysaght MJ. Maintenance dialysis population dynamics: Current trends and long-term implications. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(Suppl 1):S37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbertson DT, Liu J, Xue JL, Louis TA, Solid CA, Ebben JP, Collins AJ. Projecting the number of patients with end-stage renal disease in the United States to the year 2015. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(12):3736–3741. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang HC, Zuo Y, Fogo AB. Models of chronic kidney disease. Drug Discov Today Dis Models. 2010;7(1-2):13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmod.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nath KA. Tubulointerstitial changes as a major determinant in the progression of renal damage. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;20(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80312-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Bayati MA, Xie Y, Mohr FC, Margolin SB, Giri SN. Effect of pirfenidone against vanadate-induced kidney fibrosis in rats. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64(3):517–525. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen EP. Fibrosis causes progressive kidney failure. Med Hypotheses. 1995;45(5):459–462. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(95)90221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cattran DC, Rao P. Long-term outcome in children and adults with classic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32(1):72–79. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9669427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pei Y, Cattran D, Delmore T, Katz A, Lang A, Rance P. Evidence suggesting under-treatment in adults with idiopathic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Regional glomerulonephritis registry study. Am J Med. 1987;82(5):938–944. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Appenroth D, Lupp A, Kriegsmann J, Sawall S, Splinther J, Sommer M, Stein G, Fleck C. Temporary warm ischaemia, 5/6 nephrectomy and single uranyl nitrate administration--comparison of three models intended to cause renal fibrosis in rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2001;53(4):316–324. doi: 10.1078/0940-2993-00197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang F, Chung AC, Huang XR, Lan HY. Angiotensin II induces connective tissue growth factor and collagen I expression via transforming growth factor-beta-dependent and -independent smad pathways: The role of SMAD3. Hypertension. 2009;54(4):877–884. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.136531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klahr S, Morrissey J. Obstructive nephropathy and renal fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283(5):F861–875. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00362.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Border WA, Noble NA. Interactions of transforming growth factor-beta and angiotensin II in renal fibrosis. Hypertension . 1998;31(1 Pt 2):181–188. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsusaka T, Hymes J, Ichikawa I. Angiotensin in progressive renal diseases: Theory and practice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7(10):2025–2043. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V7102025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meran S, Steadman R. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in renal fibrosis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2011;92(3):158–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2011.00764.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Efstratiadis G, Divani M, Katsioulis E, Vergoulas G. Renal fibrosis. Hippokratia. 2009;13(4):224–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phanish MK, Winn SK, Dockrell ME. Connective tissue growth factor-(cTGF, CCN2)–a marker, mediator and therapeutic target for renal fibrosis. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2010;114(3):e83–92. doi: 10.1159/000262316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodrigues Diez R, Rodrigues-Diez R, Lavoz C, Rayego-Mateos S, Civantos E, Rodriguez-Vita J, Mezzano S, Ortiz A, Egido J, Ruiz-Ortega M. Statins inhibit angiotensin II/SMAD pathway and related vascular fibrosis, by a TGF-beta-independent process. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e14145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baeuerle PA, Henkel T. Function and activation of NF-kappa B in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:141–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee KS, Buck M, Houglum K, Chojkier M. Activation of hepatic stellate cells by TGF alpha and collagen type I is mediated by oxidative stress through c-MYB expression. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(5):2461–2468. doi: 10.1172/JCI118304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of renal fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7(12):684–696. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin SL, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA, Duffield JS. Pericytes and perivascular fibroblasts are the primary source of collagen-producing cells in obstructive fibrosis of the kidney. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(6):1617–1627. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayslett JP, Kashgarian M, Epstein FH. Functional correlates of compensatory renal hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 1968;47(4):774–799. doi: 10.1172/JCI105772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee BC, Choi JB, Cho HJ, Kim YS. Rehmannia glutinosa ameliorates the progressive renal failure induced by 5/6 nephrectomy. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122(1):131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang PH, Cenedeze MA, Campanholle G, Malheiros DM, Torres HA, Pesquero JB, Pacheco-Silva A, Camara NO. Deletion of bradykinin B1 receptor reduces renal fibrosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9(6):653–657. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bing P, Maode L, Li F, Sheng H. Expression of renal transforming growth factor-beta and its receptors in a rat model of chronic cyclosporine-induced nephropathy. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(7):2176–2179. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fassi A, Sangalli F, Maffi R, Colombi F, Mohamed EI, Brenner BM, Remuzzi G, Remuzzi A. Progressive glomerular injury in the MWF rat is predicted by inborn nephron deficit. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9(8):1399–1406. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V981399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Le Berre L, Godfrin Y, Perretto S, Smit H, Buzelin F, Kerjaschki D, Usal C, Cuturi C, Soulillou JP, Dantal J. The Buffalo/Mna rat, an animal model of FSGS recurrence after renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33(7-8):3338–3340. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02437-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]