Abstract

Endothelial cells and dental pulp cells enhance osteo-/odontogenic and angiogenic differentiation. In our previous study, rat pulp cells migrated to Nd:YAG laser-irradiated endothelial cells in an insert cell culture system. The purpose of this study was to examine the possible changes in the gene expression of cultured rat aortic endothelial cells after Nd:YAG laser irradiation using affymetrix GeneChip Array. Total RNA was extracted from the cells at 5 h after laser irradiation. Gene expressions were evaluated by DNA array chip. Up-regulated genes were related to cell migration and cell structure (membrane stretch, actin regulation and junctional complexes), neurotransmission and inflammation. Heat-shock 70 kDa protein (Hsp70) was related to the development of tooth germ. This study offers candidate genes for understanding the relationship between the laser-stimulated endothelial cells and dental pulp cells.

Keywords: Affymetrix GeneChip Array, endothelial cell, Nd:YAG laser

Dental pulp is a microcirculatory system that lacks true arteries and veins. The pulpal microcirculation is a dynamic system that regulates blood flow in response to nearby metabolic events, including dentinogenesis (1). Pulp irritation following dental procedures such as cavity preparation results in the enlargement of blood vessels in dental pulp. Perivascular stem cells proliferate in response to such irritations which are strong enough to cause odontoblast injury (2). For instance, caries induces the release of dentin matrix components that contribute to angiogenic events that support pulp regeneration (3). The response of stimulated blood vessels contributes to the initiation of dentinogenesis. Mathieu et al. reported that pulp cells migrate to injured endothelial cells if endothelial cells are damaged (4). Endothelial injury in the pulp is involved in the recruitment of odontoblast-like cells to the damaged site, and it is reported that perivascular stem cells can proliferate in response to odontoblast injury (2). We used a Nd:YAG laser as artificial stimulus of endothelial cells and confirmed that pulp cells indeed migrate to laser-irradiated endothelial cells. The migrating pulp cells expressed transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) (5). Without laser irradiation, few migrating pulp cells were observed, and the expression of mRNA for TGFβ1 was weak.

Thus, the objective of this study was to examine the gene expression of cultured rat endothelial cells after Nd:YAG laser irradiation by Affymetrix GeneChip Array.

Materials and Methods

Materials. Rat aortic endothelial cells (Cell Applications, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) were cultured in rat endothelial cell growth medium with growth supplements (Cell Applications, Inc.). A pulsed Nd:YAG laser apparatus [d-Lase 300; wavelength of 1.064 μm, a flexible fiber delivery system (∅=0.32 mm) ] was purchased from American Dental Laser, Birmingham, MI, USA.

Laser irradiation. Near-confluent endothelial cells in 6-well plates were placed at 3 mm distance from the tip of the Nd:YAG laser and exposed to laser irradiation (focused beam at a 100 mJ pulse energy and 0.5 W output power with 5 pulses/s for 30 s) five times per well, according to our previous article (5). This power output was determined as the optimal value for induction of odontoblast-like cell differentiation in the pulp cells which interact with endothelial cells (6). Control cells were not exposed to laser irradiation.

Evaluation of gene expression by DNA array chip. Total RNA was extracted from the cells at 5 hours after laser irradiation using an RNaid kit (BIO 101, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Total RNA (1 μg) was converted to cDNA using reverse transcriptase (High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Master Mix; Applied Biosystems Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

Biotinylated cRNA was synthesized by GeneChip 3’IVT Express Kit (Affymetrix) from 250 ng total RNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Biotinylated cRNA yields were checked with a NanoDrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K., Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan). Following fragmentation, 10 μg of cRNA were hybridized for 16 h at 45˚C on GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array. Arrays were washed and stained in a GeneChip Fluidics Station 450 (Affymetrix). Arrays were scanned using GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G. Single array analysis was carried out by Microarray Suite version 5.0 (MAS5.0) (7) with Affymetrix default setting and global scaling as normalization method. The trimmed mean target intensity of each array was arbitrarily set to 500.

Results

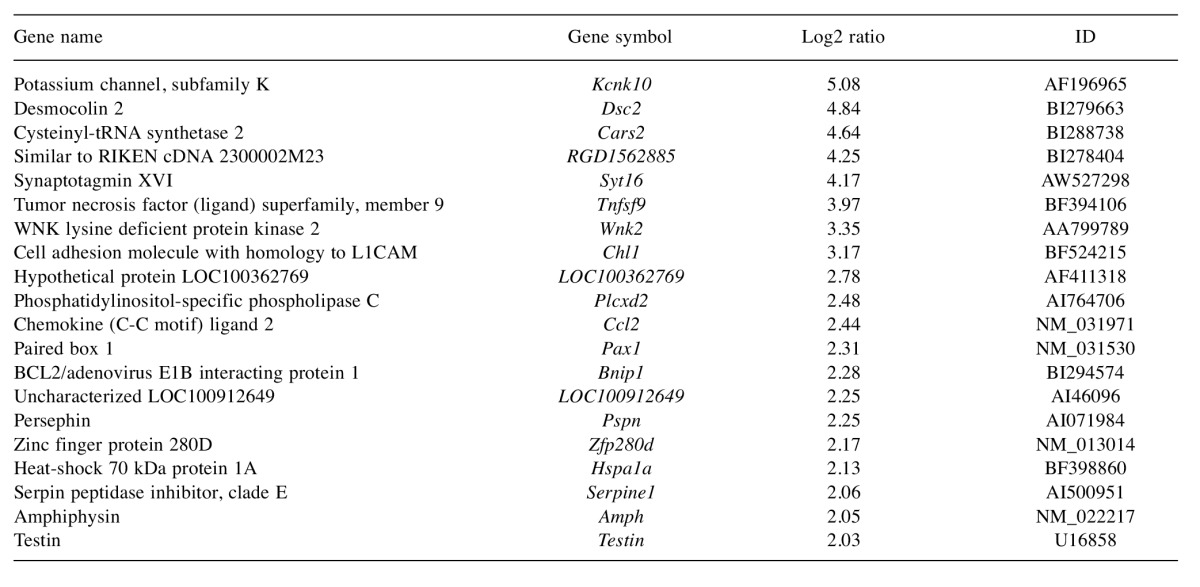

Table I shows the genes which were up-regulated by more than 4-fold compared to the control. Potassium channel, subfamily K, member 10 (Kcnk10) gene was up-regulated by more than 32-fold. Desmocollin 2 and synaptotagmin XVI were up-regulated by more than 16-fold. Wnk lysine-deficient protein kinase 2 and tumor necrosis factor superfamily were up-regulated by more than 8-fold. Heat-shock 70 kDa protein 1A gene, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (Ccl2), amphiphysin, persephin, zinc finger protein 280D, testin, phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C, and cell adhesion molecule with homology to L1CAM were up-regulated more than 4-fold. A total of 151 genes were up-regulated by more than two-fold. These included matrix metalloprotease 2 (Mmp2), chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (Cxcl1), Cxcl2, Cxcl12, Cxcl16, Cx3cl1, Ccl7, interleukin 1 receptor-like 1 (Il1rl1), Il22ra2 and heat-shock 105/110 protein 1.

Table I. Genes up-regulated by more than 4-fold.

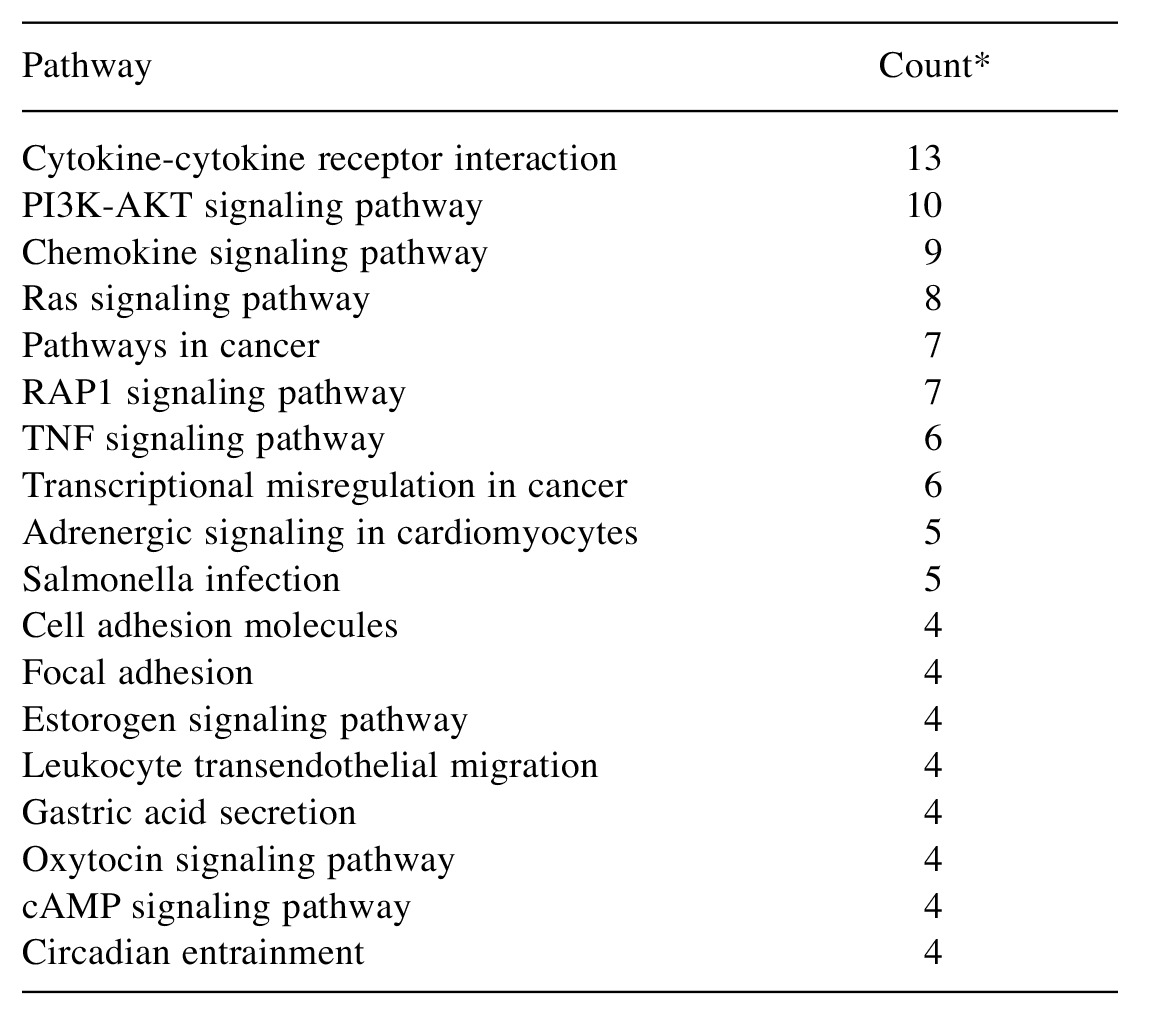

Table II shows the matched pathways associated with genes dysregulated by more than 4-fold. In the pathway of the cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, expression of 13 genes was changed. Expression of six genes encoding chemokines were increased (Cxcl2, Cxcl12, Cxcl16, Cx3Cl1, Ccl2 and Ccl7), that of four genes of the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) family were increased and two of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family were increased (Tnfrsf11b, Tnfsf9), while that of Tnfs4 was reduced by laser irradiation. In chemokine signaling pathway, expression of phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (Pik3)-related genes was reduced. In pathways of cancer, the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are related to angiogenesis, was increased. In the TNF signaling pathway, expression of genes related to leukocyte recruitment was increased. In cell adhesion molecule and oxytocin signaling pathways, expression of all genes (4 and 37 genes, respectively) decreased due to laser irradiation. In the estrogen signaling pathway, expression of Hsp70 and MMP genes increased and that of Pikc3 and calmodulin 1 (Calm1) was reduced by laser irradiation.

Table II. Matched pathways that contained 4 or more genes whose expression was up- or down-regulated by laser irradiation by more than two-fold compared to the control.

*Number of genes related to the pathway whose expression was altered by laser irradiation. P13K: Phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase; AKT: protein kinase B; TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

Discussion

The pulp houses a number of tissue elements, including axons, vascular tissue, connective tissue fibers, ground substance, interstitial fluid, odontoblasts, fibroblasts, immunocompetent cells, and other cellular components. These components respond dynamically to various stimuli (8). The pulp cells and vascular system are closely related with each other upon stimulation. Stem cells are known to occupy a perivascular niche and therefore interact with endothelial cells (9). As a stimuli, endothelial cells were irradiated with a Nd:YAG laser and pulp cells migrated toward the endothelial cells (5). After analysis of these data, we supposed that after irradiation, genes for chemokines are expressed dominantly in the endothelial cells. Among genes for chemokines, only Ccl2 was significantly expressed in this study. Nevertheless, remarkably we found that up-regulated genes were related to the form of cell structure in this study. (membrane stretch, actin regulation and junctional complexes), neuron and inflammation. In more detail, the most highly up-regulated gene (32-fold) was potassium channel subfamily K, member10 (Kcnk10). Trek2 is a well-known as potassium channel subunit which is activated by membrane stretch or acidic pH. At 240 mm Hg pressure, channel activity increased 10-fold above the basal level. In cell-attached patches, a basal level of channel activity was usually present under normal atmospheric pressure. It belongs to the class of mechanosensitive proteins (10). The pulp has limits to expansion. The total volume within the pulp chamber cannot be increased significantly. Then, inflammatory reactions result in an increase in tissue pressure. Therefore, we suppose that Kcnk10 expression is up-regulated in actual inflammatory response in vivo. Desmocollin 2 was up-regulated by more than 20-fold. Desmocollins, along with desmogleins, are cadherin-like transmembrane glycoproteins that are major components of the desmosome, which are cell–cell junctions that help resist shearing forces and are found in high concentrations in cells subjected to mechanical stress. The function of synaptotagmin XVI has not been explained.

Tnfsf9 was up-regulated almost 16-fold. It is a ligand of the TNF superfamily. TNF-α was an inflammatory mediators. Phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C, X domain-containing 2 (Plcxd2) is related to the hormone regulated intracellular signaling systems (11). Ccl2 is the chemokine, which was expressed by the unstimulated odontoblasts. The genes for CCL2, CXCL12 and CXCL14 are known to code for factors chemotactic for immature dendritic cells (12). Persephin is a glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) family ligand (13). Hsp70 gene was expressed immediately after CO2 laser irradiation in the pulp horn (14). Its expression is also increased when cells are exposed to elevated temperatures or stresses, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and nestin, which is an intermediate filament protein most related to neurofilaments of stem cells. HSP-70 was mostly expressed in enamel (15). Expression of this protein was induced by diode laser irradiation on choroide-retinal endothelial cells (16) and induced by thermal, ischemic and oxidative stress. Its hyperexpression might modulate apoptosis in choroidoretinal tissues (17). Serpin peptidase inhibitor clade E gene encodes plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1, which is the major physiological inhibitor of tissue-type and urokinase-type plasminogen activators and plays a role in obesity and insulin resistance in women but not in men (18). Amphiphysin 1, an endocytic adaptor concentrated at synapses that couples clathrin-mediated endocytosis to dynamin-dependent fission, was also shown to have a regulatory role in actin dynamics. Actin regulation is a key function of amphiphysin 1 and that such function cooperates with the endocytic adaptor role and membrane shaping/curvature sensing properties of the protein during the endocytic reaction (19). Testin is a component of cell junctions whose mRNA is predominantly expressed in the gonads (20). The expression of testin is correlated with rapid tissue remodeling in the gonads during germ cell and follicle development. Ccl2, persephin, Hsp70, Serpin peptidase inhibitor clade E gene, amphiphysin 1 and testin were expressed by more than 4-fold..

The present study demonstrated that expression of chemokine Ccl2 was increased by more than 4-fold by Nd:YAG laser irradiation. Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Cxcl12, Cxcl16, Cx3cl1 and Ccl7 were expressed more than two-fold. Alvarado reported the data of the Affimetrix cytokine gene expression after argon laser irradiation. Ccl2, ccl8, Ccl26, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Cxcl3, Cxcl5, Cxcl6 and Cxcl8 were expressed in endothelial cells of eye (21). It is highly probable that levels of chemokine expression induced by laser irradiation may depend on both the type of cell and laser. In this study, it was suggested that laser-stimulation induced the expression of the genes for mechanical sensing, neurotransmitters and chemokines significantly in the endothelial cells. To clarify the mechanism of the reparative dentine formation with laser irradiation, the analysis of gene expressions of cells after laser irradiation are crucial.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that the expression of several genes was considerably enhanced after stimulation by laser irradiation. It is important to elucidate the mechanism of up-regulation of these genes in understanding the interaction between stimulated endothelial cells and dental pulp cells.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by a Grant-In-Aid for Scientific Research (12771150,10297038) from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan. The Authors have no conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- 1.Seltzer S, Bender IB. Dental pulp. In: The Circulation of the Pulp. K.M. Hargreaves, and H.E. Goodis (eds.) Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc. pp. . 2002;Tokyo:123–150. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Téclès O, Laurent P, Zygouritsas S, Burger AS, Camps J, Dejou J, About I. Activation of human dental pulp progenitor/stem cells in response to odontoblast injury. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang R, Cooper PR, Smith G, Nör JE, Smith AJ. Angiogenic activity of dentin matrix components. J Endod. 2011;37:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathieu S, El-Battari A, Dejou J, About I. Role of injured endothelial cells in the recruitment of human pulp cells. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masuda Y, Yamada Y, Kimura Y. In vitro guidance of dental pulp cells by Nd:YAG laser-irradiated endothelial cells. Photomed Laser Surg. 2012;30:315–319. doi: 10.1089/pho.2011.3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dissanayaka WL, Zhu L, Hargreaves KM, Jin L, Zhang C. In vitro analysis of scaffold-free prevascularized microtissue spheroids containing human dental pulp cells and endothelial cells. J Endod. 2015;41:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hubbell E, Liu W-M, Mei R. Robust estimators for expression analysis. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1585–1592. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.12.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hargreaves KM, Cohen S, Berman LH. Chapter 12, Structure and Functions of the Dental-Pulp Complex. Cohen’s Pathways of the Pulp Tenth Edition. Hargreaves KM, Cohen S and Berman LH (eds.).Elsevier, Mosby Co. St. Louis, Missouri, USA, . 2015;1:452–453. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi S, Gronthos S. Perivascular niche of postnatal mesenchymal stem cells in human bone marrow and dental pulp. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:696–704. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.4.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bang H, Kim Y, Kim D. TREK-2, a new member of the mechanosensitive tandem-pore 1K channel family. J Biol Chem. 2000;23:17412–17419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smrcka AV. Regulation of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C at the nuclear envelope in cardiac myocytes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2015;65:203–210. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caux C, Vanbervliet B, Massacrier C, Ait-Yahia S, Vaura C, Chemin K, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Vicari A. Regulation of dendritic cell recruitment by chemokines. Transplantation. 2002;73:S7–11. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200201151-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sidorova YA, Mätlik K, Paveliev M, Lindahl M, Piranen E, Milbrandt J, Arumae U, Saarma M, Bespalov MM. Persephin signaling through GFRalpha1: the potential for the treatment of Parkinson. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2010;44:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee DH, Murakami S, Lhan SZ, Matsuzaka K, Inoue T. Pulp responses after CO2 laser irradiation of rat dentin. Photomed Laser Surg. 2013;31:59–64. doi: 10.1089/pho.2012.3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kero D, Kalibovic Govorko D, Medvedec Mikic I, Vukojevic K, Cigic L, Saraga-Babic M. Analysis of expression patterns of IGF-1, caspase-3 and HSP-70 in developing human tooth germs. Arch Oral Biol. 2015;60:1533–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du S, Zhang Q, Zhang S, Wang L, Lian J. Heat-shock protein 70 expression induced by diode laser irradiation on choroid-retinal endothelial cells in vitro. Mol Vis. 2012;18:2380–2387. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mainster MA, Reichel E. Transpupillary thermotherapy for age-related macular degeneration, long-pulse photocoagulation, apoptosis, and heat shock proteins. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2000;31:359–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weisz F, Bartenschlager H, Knoll A, Mileham A, Deeb N, Geldermann H, Cepica S. Association analyses of porcine SERPINE1 reveal sex-specific effects on muscling, growth, fat accretion and meat quality. Anim Genet. 2012;43:614–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2011.02295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada H, Padilla-Parra S, Park SJ, Itoh T, Chaineau M, Monaldi I, Cremona O, Benfenati F, De Camilli P, Coppey-Moisan M, Tramier M, Galli T, Takei K. Dynamic interaction of amphiphysin with N-WASP regulates actin assembly. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34244–34256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grima J, Zhu L-J, Zong SD, Catterall JF, Bardin CW, Cheng CY. Rat testin is a newly identified component of the junctional complexes in various tissues whose mRNA is predominantly expressed in the testis and ovary. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:340–355. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarado JA, Chau P, Wu J, Juster R, Shifera AS, Geske M. Profiling of cytokines secreted by conventional aqueous outflow pathway endothelial cells activated in vitro and ex vivo with laser irradiation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:7100–7108. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]