Abstract

Here we report whole exome sequencing (WES) on a cohort of 71 patients with persistently unresolved white matter abnormalities with a suspected diagnosis of leukodystrophy or genetic leukoencephalopathy. WES analyses were performed on trio, or greater, family groups. Diagnostic pathogenic variants were identified in 35% (25/71) of patients. Potentially pathogenic variants were identified in clinically relevant genes in a further 7% (5/71) of cases, giving a total yield of clinical diagnoses in 42% of individuals. These findings provide evidence that WES can substantially decrease the number of unresolved white matter cases.

Search Terms: Leukodystrophy, Whole Exome Sequencing, MRI Pattern Recognition, Incidental Findings

Introduction

Patients with white matter abnormalities in the central nervous system (CNS) may have one of over a hundred genetic disorders, including the leukodystrophies (Supplemental Table S1).1 Over the past two decades MRI pattern recognition has transformed the diagnosis of leukodystrophies.2,3 Despite these advances, the breadth of conditions that present as a possible leukodystrophy continues to challenge even the most astute clinician.4 Nearly half of these patients will remain unresolved, resulting in a prolonged diagnostic odyssey for affected families.5–7

A number of recent reports have provided evidence that whole exome sequencing (WES) can resolve previously intractable genetic disorders, with diagnostic yields ranging from 16% to 53%.8–19 Given the unmet diagnostic need amongst patients with leukodystrophy, and the potential for agnostic next generation sequencing (NGS) to clarify these cases, we performed whole exome sequencing (WES) on a cohort of 71 patients referred to the Myelin Disorders Bioregistry Project (MDBP) for unresolved leukoencephalopathy of presumed genetic etiology. These patients were collected prospectively from 8.1.2009 to 7.31.2013 in the MDBP or the Amsterdam Database of Unclassified Leukoencephalopathies with approval from the institutional review boards at all collaborating institutions including Children’s National Medical Center, the Baylor Neurogenetic Institute, and VU University Medical Center.

Methods

Cohort description

A total of 191 persistently unresolved cases were identified during the course of the study. 101 patients were diagnosed using MRI pattern recognition followed by biochemical or other molecular approaches. These testing approaches included lysosomal enzymes, very long chain fatty acids, specific electron transport chain or mitochondrial enzyme assays, urine organic acids, microarray testing of copy number variations, gross chromosomal abnormality testing by karyotype or microarry, plasma amino acids, cerebrospinal neurotransmitters and alpha interferon, urine mucopolysaccaride or sialic acid testing, and targeted molecular testing, for example for EIF2B1–5, PLP1 or GFAP sequencing based on MRI pattern recognition. Of the 90 persistently unsolved cases, 19 were excluded from WES testing: nine families obtained access to WES at other facilities, and an additional 10 families were excluded because DNA quality for all members of the trio did not meet stringency criteria and attempts to collect additional samples during the course of the study were unsuccessful. Seventy-one families remained for which high quality samples were available for complete trios. These 30 female and 47 male individuals all had abnormal white matter signal on neuroimaging. Individuals ranged in age from 3 years to 26 years at the time of sequencing, but symptom onset ranged from birth to 19 years (see complete Supplemental Case Reports available at http://imb.uq.edu.au/download/Vanderver_AON_2016.case_reports.pdf). Ethnicities were varied and included individuals of mixed and northern European descent, as well as African American, Arab, African, Asian, and Latin American origin. Radiological images and clinical summaries are provided in Supplemental Case Reports.

WES sequencing was performed at the Queensland Centre for Medical Genomics. Exomes were captured using either Illumina Nextera Rapid Capture kit or the SeqCap EZ Human Exome Library v.3.0. Captured libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 (2 × 100nt) or on an Illumina NextSeq 500 (2 × 150nt). WES sequencing was performed such that a minimum of 80% of targeted bases were sequenced to a read depth of 20× or greater (average: 88%). Reads were aligned to the reference human genome (GRCh37) and pedigree informed variant calling was performed using the Real Time Genomics (RTG) integrated analysis tool rtgFamily v3.2.20 All variants were annotated using SnpEff v3.421 and filtered using data from the SnpEff GRCh37.72 database, dbSNP138, and dbNSFP v2.4.

We utilized a custom-built variant annotation and interpretation interface to identify possible causal mutations in each case, incorporating evidence including minor allele frequency, conservation, predicted pathogenicity, disease-association (in public databases or the published literature), established or predicted biological function, confirmation with Sanger sequencing and familial segregation (Supplemental Tables S2–S4).22 Cases with variants in known disease genes meeting the ACMG criteria for pathogenic or likely pathogenic (see Supplemental Case Reports), and whose clinical features were concordant with the established gene:disease relationship were classified as diagnostically resolved.

Results

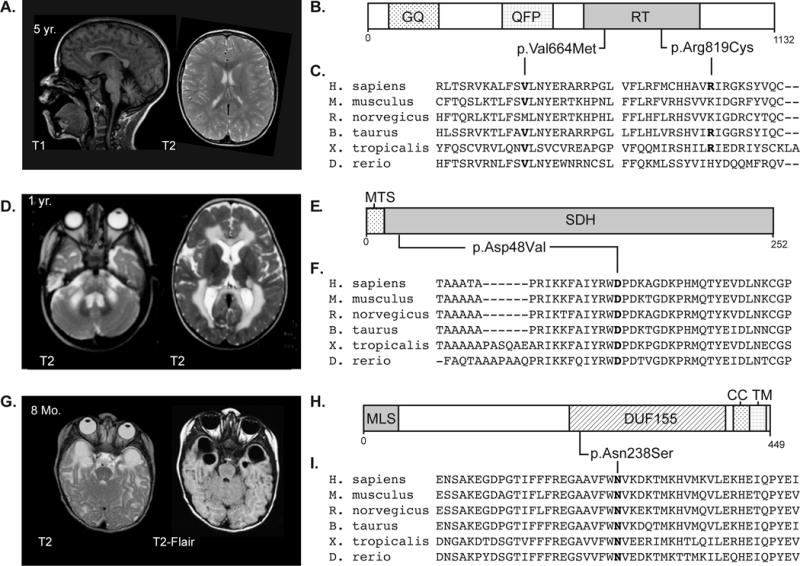

In this cohort we were able to unambiguously resolve 25 cases (Table 1, Supplemental Table S2, and Supplemental Case Reports). In three cases we were able to confirm pathogenicity with downstream biochemical testing. For example, we identified a compound heterozygous mutation in TERT (MIM:187270) in a patient that presented with white matter changes, frequent infections, mild developmental delay and hypogammaglobulinemia which was validated by Flow-FISH telomere length analysis and confirmed a diagnosis of atypical Dyskeratosis Congenita with hypomyelination (MIM:613989) (Figure 1, Supplemental Case Reports, LD_0607.0).23 Likewise, an individual with a compound heterozygous mutation in GLB1 (MIM:611458) had confirmatory lysosomal enzyme testing (Supplemental Case Reports, LD_0846.0), and an individual with mutations in ATM (MIM:607585) had confirmatory elevated alpha-fetoprotein levels (Supplemental Case Reports, LD_0678.0).

Table 1.

Cases with pathogenic variants identified by exome sequencing in classical leukodystrophy genes.

| Family | Gene | Zygosity | Protein | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD_0139 | TUBB4A | Het, de novo | p.Arg391His | Likely pathogenic |

|

| ||||

| LD_0181 | DARS | Het | p.Arg494Gly | Likely pathogenic |

| Het | p.Arg460His | Likely pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| LD_0604 | POLR3B | Het | p.Glu271fs | Pathogenic |

| Het | p.Val523Glu | Pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| LD_0672 | TUBB4A | Het, de novo | p.Val180Gly | Likely pathogenic |

|

| ||||

| LD_0764 | EIF2B5 | Het | p.Gln562* | Pathogenic |

| Het | p.Arg339Trp | Pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| LD_0774 | POLR1C | Het | p.Lys295del | Likely pathogenic |

| Het | p.Cys146Arg | Likely pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| LD_0869 | EIF2B2 | Het | p.Gly200Val | Pathogenic |

| Het | p.Glu213Gly | Pathogenic | ||

Key: Het –Heterozygous; Hom – Homozygous; rs – Reference Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms

Figure 1. MRI and pathogenic variants for three cases.

A) MRI of individual LD_0607.0 – a male of mixed European descent with a multisystem disorder characterized by elevated creatine kinase, recurrent infection with hypogammaglobulinemia, dyskeratosis congenita, and mild transaminase abnormalities. MRI revealed moderate cerebellar atrophy and diffuse multifocal white matter changes. Follow-up MRI one year later showed unchanged T2 hyperintensities. The variants found in TERT in this patient were classified as pathogenic per the ACMG guidelines and the diagnosis was supported by telomere length analysis (data not shown). B) Schematic of the TERT protein showing heterozygous variants identified in LD_0607.0. Predicted domains: GQ, GQ motif; QFP, QFP motif; RT, Reverse transcriptase domain. C) Clustalo alignment of vertebrate homologs of TERT showing conservation of mutated residues. D) MRI of individual LD_0756.0 – male of Turkish descent with motor delays were noted at birth who abruptly decompensated at 7 months of age, and a history of ataxia, hypotonia, and spasticity. MRI at 3 years and 6 months of age was significant for signal abnormality of the supratentorial white matter with sparing of the U fibers, a swollen appearance to the corpus callosum, involvement of the cerebellar white matter, and the brain stem. This pattern has been seen in previously published cases and supports the SDHB variant categorization as potentially pathogenic. E) Schematic of the SDHB protein showing a homozygous variant identified in LD_0756.0. Predicted domains: MTS, mitochondrial targeting signal; SDH, Succinate dehydrogenase domain. F) Clustalo alignment of vertebrate homologs of SDHB showing conservation of mutated residues. G) MRI of individual LD_0286.0B – male of mixed-European descent with leukoencephalopathy and a history of sensorineural hearing loss, developmental delay and febrile seizures. MRI is significant for bilateral temporal lobe cysts, small corpus callosum, and periatrial white matter abnormalities. Hearing loss and other clinical manifestations were consistent with the phenotype reported for mutations in RMND1, and the variant was classified as likely pathogenic based on supporting evidence. H) Schematic of the RMND1 protein showing heterozygous variants identified in LD_0286. Predicted domains: MLS, mitochondrial localization signal; DUF155, domain of unknown function 155; CC, coiled-coil domain; and TM, trans-membrane domain. I) Clustalo alignment of vertebrate homologs of RMND1 showing conservation of mutated residues.

Nine of the twenty-five cases had mutations in genes associated with disorders classically defined as leukodystrophies3 (Table 1 & Supplemental Table S1): two patients were identified with TUBB4A (MIM:602662) related hypomyelination (Hypomyelination with atrophy of the basal ganglia and cerebellum [MIM:612438])24; two patients were identified with early onset Vanishing White Matter Disease (MIM:603896) (genotype EIF2B2 [MIM:606454] and EIF2B5 [MIM:603945])25, 26; three families were identified with t-RNA synthetase disorders (AARS [MIM:601065] and DARS [MIM:603084])27–29; and two families identified with a POLR3-related disorder (POLR3B [MIM:614366] and POLR1C [MIM:610060]) (Table 1, Supplemental Table S2 and Supplemental Case Reports).30 The remaining individuals had mutations in genes associated with genetic leukoencephalopathies. In these cases expert review confirmed that the clinical presentation and MR imaging was consistent with published phenotypes. These findings are consistent with the estimation that a majority of disorders associated with abnormal white matter on neuroimaging are not classic leukodystrophies.1 This suggests that testing of leukodystrophy-associated genes on NGS panels may have limited diagnostic efficacy (predicted to be only 13% in this cohort), which may outweigh the perceived cost benefit and limiting exposure to incidental findings.

In a further four cases we identified one or more potentially damaging variants of uncertain significance (VUS) that did not reach the strict burden of proof required to be classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic. In each of these cases the neuroradiological findings, clinical features and familial segregation of the variants in these individuals were consistent with the published phenotype (Table 2, Supplemental Table S3, and Supplemental Case Reports). We therefore classified these variants as potentially pathogenic and considered the cases clinically resolved by expert assessment. This included cases with variants in AMPD2, FLNA, and NDUFA2 (Supplemental Table S4). This also included one case (LD_0675) where the individual was reported as part of cohort describing a novel disease due to mutations in AARS2.27

Table 2.

Cases with pathogenic variants identified by WES in genes not associated with leukodystrophy.

| Family | Gene | Zygosity | Protein | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD_0106 | GRIN1 | Het, de novo | p.Arg865Cys | Likely pathogenic |

|

| ||||

| LD_0115 | AARS | Het | p.Arg751Gly | Pathogenic |

| Het | p.Lys81Thr | Pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| LD_0119 | KCNT1 | Het, de novo | p.Phe932Ile | Pathogenic |

|

| ||||

| LD_0157 | SZT2 | Het, de novo | p.Pro1833fs | Pathogenic |

| Het | p.Gly2306Arg | Likely pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| LD_0158 | CNTNAP1 | Hom | p.Arg388Pro | Likely pathogenic |

|

| ||||

| LD_0232 | MRPS22 | Het | p.Lys248fs | Pathogenic |

|

| ||||

| Het | p.Arg191Gln | Likely pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| LD_0286 | RMND1 | Hom | p.Asn238Ser | Likely pathogenic |

|

| ||||

| LD_0333 | CNTNAP1 | Het | p.Arg107* | Pathogenic |

| Het | p.Cys323Arg | Likely Pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| LD_0358 | STXBP1 | Het, de novo | p.Arg367* | Pathogenic |

|

| ||||

| LD_0366 | GATAD2B | Het, de novo | p.Gln274* | Pathogenic |

|

| ||||

| LD_0463 | ALS2 | Het | p.Arg1139* | Pathogenic |

| Het | p.Gly1083Glu | Pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| LD_0607 | TERT | Het, de novo | p.Arg819Cys | Pathogenic |

| Het | p.Val664Met | Pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| LD_064619 | NDUFS7 | Hom | p.Arg135Cys | Likely pathogenic |

|

| ||||

| LD_0678 | ATM | Het | p.Leu275fs | Pathogenic |

| Het | p.Lys2756* | Pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| LD_0755 | SDHAF1 | Hom | p.Arg55Pro | Pathogenic |

|

| ||||

| LD_0756 | SDHB | Hom | p.Asp48Val | Pathogenic |

|

| ||||

| LD_0846 | GLB1 | Het | p.Arg196Ser | Pathogenic |

| Het | p.Tyr240His | Pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| LD_0857 | AARS | Hom | p.Arg751Gly | Pathogenic |

Key: Het –Heterozygous; Hom – Homozygous;

A final case had a de novo variant in FUS (MIM:205100) classified as pathogenic by ACMG criteria, but because this gene has previously only been associated with only juvenile or adult onset Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), this was not considered an unambiguous resolution (Table 2, Supplemental Table S3 & Supplemental Case Reports). However, because mutations in other ALS associated genes are associated with early hypomyelination (including ALS2 [MIM:205100] in this cohort), and because the de novo finding segregated in this family, it was classified as a potentially pathogenic variant and a clinically resolved case.

To investigate the burden of actionable incidental findings that may be identified during trio-based WES investigation of rare genetic disorders, the Illumina Clinical Services Laboratory screened all 56 adult and 49 pediatric ACMG recommended genes for potential incidental variants.31 This analysis revealed pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in 3 of the 71 families screened (Table 3). The identified variants were restricted to KCNQ1 (MIM:607542) associated with long QT syndrome and SDHB (MIM:115310) associated with hereditary paragangliomas (Table 2, Supplemental Table S3 and Supplemental Case Reports). Interestingly, mutations in SDHB are also now associated with autosomal recessive succinate dehydrogenase deficiency associated leukoencephalopathy, although the lack of a second mutation in LD_0315 precluded definitive association of this genotype with the patient’s phenotype.32 We found less than one known pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant per 46 adult exomes analyzed, suggesting that the impact of incidental findings is likely to be minimal, especially when weighed against the potential benefits of a successful genetic diagnosis in families with severe, life-threatening neurologic illnesses (Table 4).

Table 3.

Cases with potentially pathogenic variants identified with whole exome sequencing.

| Family | Gene | Zygosity | Protein | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD_0493 | FLNA | Hem, de novo | p.Leu2271Arg | VUS |

|

| ||||

| LD_0664 | FUS | Het | p.Gly500fs | Pathogenic |

|

| ||||

| LD_0673 | AMPD2 | Hom | p.Arg843His | VUS |

|

| ||||

| LD_0675 | AARS2 | Het | p.Gly965Arg | Likely pathogenic |

| Het | p.Glu405Lys | VUS | ||

|

| ||||

| LD_0821 | NDUFA2 | Het | p.Lys45Thr | VUS |

| Het | p.Thr75fs | VUS | ||

Key: Het –Heterozygous; Hom – Homozygous;

Table 4.

Incidental Findings Identified in Cohort

| Number of individuals screened | Number of individuals with incidental findings | Reported Incidental Finding | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unaffected Adults | 142 | 3 (2.1%) |

KCNQ1 (NM_000218.2) c.514G>A KCNQ1 (NM_000218.2) c.1189C>T SDHB (NM_003000.2) c.541-2A>G |

| Affected Children | 79 | 3 (3.7%) | As above

|

| Unaffected Siblings | 10 | 0 | NA

|

Discussion

Using an intention to treat analysis,33 and if the combined initial cohort of 191 families is considered in which 101 families achieved a diagnosis through standard approaches, the use of WES approach would result in an ~20% diagnostic increase. This yields an overall rate of diagnosis of ~72% for the combination of standard and WES approaches. Clinical integration of WES (or whole genome sequencing) therefore, may decrease the number of patients with unsolved genetic white matter disorders from 50% to less than 30%. Taking into consideration the clinical and psychosocial costs of prolonged diagnostic odysseys in these families, this is substantial.

Additionally, while the clinical utility of WES as measured by changes to patient care was not addressed in this study, it should be noted that in several cases the results of WES directly influenced clinical care. For example, patients with ATM and TERT mutations were both referred to specialist clinics where they now undergo oncologic monitoring, and the patient with a de novo KCNT1 mutation was treated with a potassium channel anticonvulsant to control refractory epilepsy.34

The use of WES in large cohorts enables the identification of sequence variants of varying degrees of clinical certainty. ACMG criteria classify the spectrum of identified variants into four tiers; pathogenic, likely pathogenic, variant of unknown significance, or unresolved.35 However, our study, in which 4 of 31 cases were resolved with MRI pattern recognition2, 3, 36, 37 and clinical review of the identified variant, suggests that a variant classification system that takes into account clinical context and downstream clinical evaluation and testing (e.g. MRI interpretation) should be considered.

In summary, WES has the potential to decrease the number of unsolved cases of leukodystrophy and genetic leukoencephalopathies. Additional research is needed establish the potential value of NGS as a first-line diagnostic tool, and to assess the comparative effectiveness of WES, WGS and targeted panels in this disease population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families. AV, GH, AP, JLS, AT, and JLPM are supported by the Myelin Disorders Bioregistry Project. GH was supported by the Delman Fund for Pediatric Neurology and Education. This publication was supported by Award Number UL1TR000075 from the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. We thank the QCMG and IMB sequencing facility teams for their assistance with this project. Computational support was provided by the NeCTAR Genomics Virtual Laboratory and QRIScloud programs. GB has received a Research Scholar Junior 1 award from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec en Santé (FRQS). R.J.T. was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award. This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia Grant (APP1068278) and a University of Queensland Foundation Research Excellence Award. NIW and MSvdK were supported by ZonMw TOP grant number 91211005. BLF reports funding from NIH Grants K08MH086297 (NIMH) and R01NS082094 (NINDS). We also thank, Brian P. Brooks, Sara Zondag, Lisa Green, Sudeshna Mitra, Lucy Civitello, Natasha Shur, Valeria Zincke, Silvia Delgado, Janice E. Brunstrom-Hernandez, Celia Chang, Robert Keating, Jessica Carpenter, Jayne Antony, Shekeeb Mohammad, Marc C. Patterson, Tarannum Lateef, Taeun Chang, James Reese, Shaaron Towns, Diego Preciado, Dewi Depositario-Cabacar, Meganne Leach, Catherine Zorc, Jenny Wilson, Eileen Walters, Steven Leber, Srikanth Muppidi, Kimberly Chapman, Amy Waldman, and Lindsey Scussel for patient referrals to the Myelin Disorders Bioregistry Project.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

AV, CS, GH and RJT designed and managed the project, coordinated the manuscript, and performed literature and case review. CS, GH, JC, AK, VR, ER, SC, TH, DM, KR, GJB, SMG, LC, JoDev, NM, AT, and RJT acquired the data and performed analysis of the incidental findings and provided bioinformatics analysis and expertise and performed laboratory studies. AV, CS, GH, JC, AP, NIW, GB, AP, JLS, MB, SHE, JLPM, BLF, RS, MSvdK, and RJT drafted the manuscript and figures.

The Leukodystrophy Study group includes ALG, TS, PLP, EF, SP, BHC, JDR, MRN, CY, YS, MD, EF, LG, CML, CTR, JaDes, HA, KW, VL, MJG, MC, IK, DG, MG, and EDR, who evaluated the patients clinically and referred patients to the Myelin Disorders Bioregistry Project. Their affiliations are included in the supplemental text.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

AV receives funding from Illumina, Inc., Gilead Sciences Inc., Eli Lilly & Co. and Shire Plc. AK, VR, ER, SC, TH, and RJT are employees of Illumina, Inc. The rest of the authors report no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Data

The Supplemental Data for this manuscript includes three tables, and a link to the Supplemental Case Reports including MRI figures from all patients where imaging was available (http://imb.uq.edu.au/download/Vanderver_AON_2016.case_reports.pdf).

Bibliography

- 1.Vanderver A, Prust M, Tonduti D, et al. Case definition and classification of leukodystrophies and leukoencephalopathies. Mol Genet Metab. 2015 Apr;114(4):494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiffmann R, van der Knaap MS. Invited article: an MRI-based approach to the diagnosis of white matter disorders. Neurology. 2009 Feb 24;72(8):750–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000343049.00540.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanderver A, Tonduti D, Schiffmann R, Schmidt J, Van der Knaap MS. Leukodystrophy Overview. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Fong CT, Smith RJH, et al., editors. GeneReviews(R) Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2014. All rights reserved. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parikh S, Bernard G, Leventer RJ, et al. A clinical approach to the diagnosis of patients with leukodystrophies and genetic leukoencephelopathies. Mol Genet Metab. 2015 Apr;114(4):501–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.12.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Knaap MS, Breiter SN, Naidu S, Hart AA, Valk J. Defining and categorizing leukoencephalopathies of unknown origin: MR imaging approach. Radiology. 1999 Oct;213(1):121–33. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.1.r99se01121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanderver A, Hussey H, Schmidt JL, Pastor W, Hoffman HJ. Relative incidence of inherited white matter disorders in childhood to acquired pediatric demyelinating disorders. Seminars in pediatric neurology. 2012 Dec;19(4):219–23. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steenweg ME, Vanderver A, Blaser S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging pattern recognition in hypomyelinating disorders. Brain. 2010 Oct;133(10):2971–82. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Y, Muzny DM, Reid JG, et al. Clinical whole-exome sequencing for the diagnosis of mendelian disorders. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 Oct 17;369(16):1502–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Athanasakis E, Licastro D, Faletra F, et al. Next generation sequencing in nonsyndromic intellectual disability: from a negative molecular karyotype to a possible causative mutation detection. American journal of medical genetics Part A. 2014 Jan;164A(1):170–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Ligt J, Willemsen MH, van Bon BW, et al. Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Nov 15;367(20):1921–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen AS, Berkovic SF, Cossette P, et al. De novo mutations in epileptic encephalopathies. Nature. 2013 Sep 12;501(7466):217–21. doi: 10.1038/nature12439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srivastava S, Cohen JS, Vernon H, et al. Clinical Whole Exome Sequencing in Child Neurology Practice. Annals of neurology. 2014 Aug 18; doi: 10.1002/ana.24251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guerreiro R, Kara E, Le Ber I, et al. Genetic analysis of inherited leukodystrophies: genotype-phenotype correlations in the CSF1R gene. JAMA neurology. 2013 Jul;70(7):875–82. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bamshad MJ, Ng SB, Bigham AW, et al. Exome sequencing as a tool for Mendelian disease gene discovery. Nature reviews Genetics. 2011 Nov;12(11):745–55. doi: 10.1038/nrg3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng SB, Nickerson DA, Bamshad MJ, Shendure J. Massively parallel sequencing and rare disease. Human molecular genetics. 2010 Oct 15;19(R2):R119–24. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Worthey EA, Mayer AN, Syverson GD, et al. Making a definitive diagnosis: successful clinical application of whole exome sequencing in a child with intractable inflammatory bowel disease. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2011 Mar;13(3):255–62. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182088158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawyer SL, Hartley T, Dyment DA, et al. Utility of whole-exome sequencing for those near the end of the diagnostic odyssey: time to address gaps in care. Clin Genet. 2015 Aug 18; doi: 10.1111/cge.12654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makrythanasis P, Nelis M, Santoni FA, et al. Diagnostic Exome Sequencing to Elucidate the Genetic Basis of Likely Recessive Disorders in Consanguineous Families. Hum Mutat. 2014 Jul 17; doi: 10.1002/humu.22617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fogel BL, Lee H, Deignan JL, et al. Exome Sequencing in the Clinical Diagnosis of Sporadic or Familial Cerebellar Ataxia. JAMA neurology. 2014 Aug 18; doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joint variant and de novo mutation identification on pedigrees from high-throughput sequencing data., 2014.

- 21.A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3., 2012.

- 22.Taylor JC, Martin HC, Lise S, et al. Factors influencing success of clinical genome sequencing across a broad spectrum of disorders. Nat Genet. 2015 Jul;47(7):717–26. doi: 10.1038/ng.3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ip P, Knight R, Dokal I, Manzur AY, Muntoni F. Peripheral neuropathy–a novel finding in dyskeratosis congenita. European journal of paediatric neurology : EJPN : official journal of the European Paediatric Neurology Society. 2005;9(2):85–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simons C, Wolf NI, McNeil N, et al. A de novo mutation in the beta-tubulin gene TUBB4A results in the leukoencephalopathy hypomyelination with atrophy of the basal ganglia and cerebellum. American journal of human genetics. 2013 May 2;92(5):767–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Knaap MS, Barth PG, Gabreels FJ, et al. A new leukoencephalopathy with vanishing white matter. Neurology. 1997 Apr;48(4):845–55. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.4.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Knaap MS, Pronk JC, Scheper GC. Vanishing white matter disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2006;5(5):413–23. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70440-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dallabona C, Diodato D, Kevelam SH, et al. Novel (ovario) leukodystrophy related to AARS2 mutations. Neurology. 2014 Jun 10;82(23):2063–71. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taft RJ, Vanderver A, Leventer RJ, et al. Mutations in DARS cause hypomyelination with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and leg spasticity. American journal of human genetics. 2013 May 2;92(5):774–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simons C, Griffin L, Helman G, et al. Loss-of-function alanyl-tRNA synthetase mutations cause an autosomal recessive persistent myelination defect and early onset epileptic encephalopathy. Submitted to American Journal of Human Genetics. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tetreault M, Choquet K, Orcesi S, et al. Recessive Mutations in POLR3B, Encoding the Second Largest Subunit of Pol III, Cause a Rare Hypomyelinating Leukodystrophy. American journal of human genetics. 2011 Oct 26; doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, et al. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2013 Jul;15(7):565–74. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alston CL, Davison JE, Meloni F, et al. Recessive germline SDHA and SDHB mutations causing leukodystrophy and isolated mitochondrial complex II deficiency. J Med Genet. 2012 Sep;49(9):569–77. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lachin JM. Statistical considerations in the intent-to-treat principle. Controlled clinical trials. 2000 Jun;21(3):167–89. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanderver A, Simons C, Schmidt JL, et al. Identification of a novel de novo p.Phe932Ile KCNT1 mutation in a patient with leukoencephalopathy and severe epilepsy. Pediatric neurology. 2014 Jan;50(1):112–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2015 May;17(5):405–24. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Knaap M, Valk J. Magnetic Resonance of Myelination and Myelin Disorders 3 ed. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiffmann R., MS vdK The latest on leukodystrophies. Current opinion in neurology. 2004;17:187–92. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200404000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.