Combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) decreases sexual and mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 through the suppression of plasma HIV-1 RNA levels.1,2 Usually, plasma HIV-1 RNA levels are used as a surrogate measure of the presence of HIV in genital tract, in terms of transmission risk.3 Although genital and plasma HIV-1 RNA are strongly correlated,4-6 some women on cART with undetectable plasma viral loads (PVLs) have been reported to shed genital HIV-1 RNA,4,5,7-11 suggesting the existence of some compartmentalization of HIV-1 in the female genital tract.12,13

Several conditions can increase the risk for female genital HIV-1 shedding, including genital infections,14 oral contraceptive use,15 pregnancy16 and pharmacology of antiretroviral agents in use.7,8,17 Nevertheless, there are few studies concerning the effects of cART on cervico-vaginal HIV-1 shedding.

We reported on a descriptive cross-sectional study of 90 women primarily on cART, for whom blood plasma and vaginal swab HIV-1 RNA specimens were measured. Our objective was to determine the frequency and the determinants of vaginal HIV-1 RNA shedding in this cohort of HIV-1 infected women. The study participants were recruited among HIV-1 infected patients referring to Unit of Infectious Diseases, San Martino Hospital, Genoa, Italy. HIV-1 infected women who gave written informed consent to the study between March 2014 and March 2015 were consecutively enrolled. Eligibility criteria were: HIV-1 infection and age ≥ 18 y. Criteria for exclusion included: pregnancy and active menstruation. The study was approved by the Regional Liguria Ethical Committee (Register Number 396REG2014).

The sample size, estimated of 80 patients, was calculated according to the 25% cervico-vaginal HIV-1 shedding prevalence in a cohort of HIV-1 infected Italian women, as observed by others,6 considering a precision level of 2% and a confidence interval (CI) of 95%. Baseline demographic characteristics, medical, immunological and sexual histories, including Treponema pallidum serology, were collected at screening. Collected vaginal swabs were tested for vaginal bacteria, Candida, Trichomonas vaginalis and Herpes Simplex Virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection according to routine microbiological methods. Cervical swabs for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma and Mycoplasma nucleic acid, Papaniculaou (Pap) smears and Hybrid Capture II HPV (HCII) test were also obtained. Pap smears were categorized according to the 2001 Bethesda system.18

Regarding antiretroviral therapy (ART), women were classified as follows: I) receiving cART, when they were taking 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and one among non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) or protease inhibitors (PI) or integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTI) or maraviroc (MCV); II) receiving mono-/dual-therapy, when they were taking mono-therapy with a PI or a dual-therapy with a PI and one among INSTI or NRTI or NNRTI or with a INSTI and one among NRTI or NNRTI; III) naive, when women had never received antiretroviral treatment; IV) off treatment, when women had been treated with antiretrovirals, but at the time of screening they had interrupted the treatment for at least 3 months.

Vaginal swabs were collected, after introduction of a speculum, by gently rolling a plastic-handled Dacron swab against the posterior fornix of vagina. The Dacron swabs were placed in a sterile transport tube with 3 ml universal viral transport medium (Anyplex II STI-7 kit). After centrifugation (1,500 g for 10 minutes), the vaginal secretions (supernatant) were removed, aliquoted and frozen at −80°C.

HIV-1 RNA load was measured on paired plasma and vaginal swabs by real time PCR assay. HIV-1 RNA quantification in plasma samples was performed using the Versant HIV-1 RNA 1.0 Assay (kPCR) kit (Siemens HealthCare Diagnostics) according to manufacturer's instructions. The lower limit of detection of the test was 37 copies/ml. HIV-1 RNA levels in vaginal secretions were measured using the NucliSENS EasyQ®, version 2.0 kit (Biomérieux SA). The lower limit of detection was 25 copies/ml on liquid retention swab. The amplification of the human RNase P gene was made as internal positive control to verify the cellularity, the entire PCR process and the detection of PCR reaction inhibitors. The vaginal swabs without a correct amplification of internal calibrators and of the human RNase P gene were considered invalid. Viral sequencing was performed both on plasma and vaginal swabs of women with detectable VL, using the Trugene HIV-1 Genotyping Kit (Siemens HealthCare Diagnostics), according to the manufacturer's recommendations after automatic extraction through the NucliSens EasyMAG instrument (Biomerieux SA).

With regards to the presence or absence of HIV-1 RNA either in plasma or in vagina, women were classified into the following 4 groups: I) HIV-1 RNA undetectable both in plasma and vaginal samples; II) HIV-1 RNA detectable in plasma and undetectable in vaginal samples; III) HIV-1 RNA detectable both in plasma and vaginal samples; IV) HIV-1 RNA detectable in vaginal samples and undetectable in plasma. The women of the third and fourth groups were defined “vaginal HIV-1 shedders.”

Continuous variables were given as median with range and percentages, categorical variables as number and/or percentage of subjects. An univariate analysis was performed using the Fisher's Exact or Wilcoxon Rank test to investigate the association of the vaginal HIV-1 RNA shedding (defined as detected or undetected) with age, smoking habits, alcohol, disease duration, PVL, CD4 cell count, exposure category, stage of the disease (according to the Center for Disease Control Classification System for HIV infection), ART, months of ART, serologic status for Treponema pallidum, genital bacterial or fungal infection, genital detection of Ureaplasma, Mycoplasma or HSV-2, cervical cytology, high risk HPV (HR-HPV) infection, menopause and hysterectomy. The estimated p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons by the Bonferroni correction method. Those variables with a p-value <0.05 were then selected for the multivariate analysis, where the vaginal HIV-1 RNA shedding was the dependent variable. Multivariate analysis was performed using again the binary Firth's penalized-likelihood logistic regression and the model selection was done by the Akaike an Information Criterion. Differences, with a p-value less than 0.05, were selected as significant in all comparisons. Data were acquired and analyzed in R v3.0.1 software environment.19

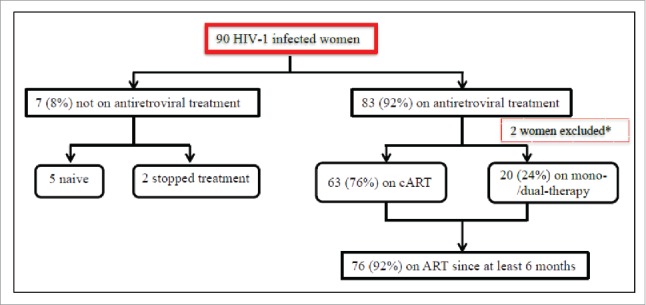

Of 90 HIV-1 infected women enrolled in the study, 2 women were excluded from analysis because their vaginal samples were considered invalid for detection of HIV-1 RNA. The demographic, and clinical characteristics of the 88 study participants are summarized in Table 1. Briefly, 89% of women were Caucasian and the median age was of 46 y. The risk category for HIV infection was heterosexual intercourse in 65 cases (74%) and the use of injected drugs in 14 cases (16%). Thirty-two women (37%) had a HCV co-infection. The clinical stage of HIV-1 infection, according to the Center for Disease Control (CDC) Classification system, was stage A in 45 (51%) and C in 21 (24%) cases. Women had been diagnosed for HIV-1 infection for a median of 18 months (range, 1 month – 31 years) and had median nadir and current CD4 cell count of 258 and 678/mm3, respectively. At the time of enrolment, 7 women (8%) were not on treatment (5 were naïve and 2 were off treatment), while the remaining 83 women (92%) were receiving ART (63 cART and 20 mono-/dual-therapy), as shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and output of univariate analysis of the study participants (N = 88).

| Vaginal HIV-1 shedding |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Negative (%)*,# | Positive (%)*,† | ||

| Characteristic | 88 (100%) | 79 (90%) | 9 (10%) | p-value |

| Age | 45.07 (9.72) | 45.09 (9.73) | 44.89 (10.23) | 1.0000 |

| HIV Disease Duration | 16.58 (9.73) | 17 (9.35) | 12.95 (12.64) | 0.4193 |

| Race | 1.0000 | |||

| Caucasian | 78 (88.64%) | 70 (89.74%) | 8 (10.26%) | |

| Others | 10 (11.36%) | 9 (90%) | 1 (10%) | |

| Smoking habits | 1.0000 | |||

| No | 42 (47.73%) | 37 (88.1%) | 5 (11.9%) | |

| Yes | 46 (52.27%) | 42 (91.3%) | 4 (8.7%) | |

| Alcohol | 1.0000 | |||

| No | 72 (81.82%) | 64 (88.89%) | 8 (11.11%) | |

| Yes | 16 (18.18%) | 15 (93.75%) | 1 (6.25%) | |

| Plasma HIV-1 viral load | <0.0001 | |||

| Undetectable (<37 cp/ml) | 71 (80.68%) | 71 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Detectable (≥37 cp/ml) | 17 (19.32%) | 8 (47.06%) | 9 (52.94%) | |

| CD4 cell count (cells/mm3) | 0.0493 | |||

| ≤350 | 15 (17.05%) | 10 (66.67%) | 5 (33.33%) | |

| 351–500 | 14 (15.91%) | 12 (85.71%) | 2 (14.29%) | |

| >500 | 59 (67.05%) | 57 (96.61%) | 2 (3.39%) | |

| HIV risk factorsa | 1.0000 | |||

| Heterosexual sex | 65 (73.86%) | 56 (86.15%) | 9 (13.85%) | |

| Injected drugs use | 14 (15.91%) | 14 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Materno fetal | 5 (5.68%) | 5 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 4 (4.55%) | 4 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| CDC Stage | 1.0000 | |||

| Stage A | 45 (51.14%) | 41 (91.11%) | 4 (8.89%) | |

| Stage B | 22 (25%) | 19 (86.36%) | 3 (13.64%) | |

| Stage C | 21 (23.86%) | 19 (90.48%) | 2 (9.52%) | |

| Antiretroviral therapy | <0.0001 | |||

| Not treated | 7 (7.95%) | 1 (14.29%) | 6 (85.71%) | |

| On treatment | 81 (92.05%) | 78 (96.3%) | 3 (3.7%) | |

| Months on current ART regimen | <0.0001 | |||

| none | 7 (7.95%) | 1 (14.29%) | 6 (85.71%) | |

| <6 months | 6 (6.82%) | 4 (66.67%) | 2 (33.33%) | |

| ≥6 months | 75 (85.23%) | 74 (98.67%) | 1 (1.33%) | |

| TPHA | 1.0000 | |||

| Negative | 83 (94.32%) | 74 (89.16%) | 9 (10.84%) | |

| Positive | 5 (5.68%) | 5 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Vaginal bacteria and/or fungib | 1.0000 | |||

| Negative | 29 (32.95%) | 27 (93.1%) | 2 (6.9%) | |

| Positive | 59 (67.05%) | 52 (88.14%) | 7 (11.86%) | |

| Herpes simplex virus 2c | 1.0000 | |||

| Negative | 79 (95.18%) | 73 (92.41%) | 6 (7.59%) | |

| Positive | 4 (4.82%) | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | |

| Ureaplasmac | 1.0000 | |||

| Negative | 75 (89.29%) | 68 (90.67%) | 7 (9.33%) | |

| Positive | 9 (10.71%) | 9 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Mycoplasmac | 1.0000 | |||

| Negative | 66 (78.57%) | 61 (92.42%) | 5 (7.58%) | |

| Positive | 18 (21.43%) | 16 (88.89%) | 2 (11.11%) | |

| Cervical cytologyd | 0.1396 | |||

| Normal | 54 (63.53%) | 51 (94.44%) | 3 (5.56%) | |

| ASCUS | 11 (12.94%) | 11 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| LSIL/HSIL | 20 (23.53%) | 14 (70%) | 6 (30%) | |

| HR-HPVe | 1.0000 | |||

| Negative | 57 (69.51%) | 53 (92.98%) | 4 (7.02%) | |

| Positive | 25 (30.49%) | 21 (84%) | 4 (16%) | |

| Menopause | 1.0000 | |||

| Not menopause | 50 (56.82%) | 46 (92%) | 4 (8%) | |

| Menopause | 38 (43.18%) | 33 (86.84%) | 5 (13.16%) | |

| Hysterectomy | 1.0000 | |||

| Not performed | 82 (93.18%) | 74 (90.24%) | 8 (9.76%) | |

| Performed | 6 (6.82%) | 5 (83.33%) | 1 (16.67%) | |

Notes. The results are expressed as mean with standard deviation or as number of subjects with percentage for the descriptive statistics. Characteristic: variable taken into account; p-value: univariate analysis p-value adjusted by using Bonferroni method (see the text for abbreviations and further details).

Percentages exclude unknown results;

HIV-1 RNA undetectable in vagina (<25 copies/ml);

HIV-1 RNA detectable in vagina (≥25 copies/ml);

Patients with multiple risk factors (heterosexual sex and injected drugs use) were included in the group of heterosexual risk factor;

Grown on vaginal swabs;

Detected by PCR;

by Papanicolau smears;

Detected by Hybrid Capture II test.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; TPHA, Treponema Pallidum Haemoagglutination Assay; ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; LSIL, low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; HSIL, high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; HR-HPV, high risk Human Papillomavirus.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the cohort profile. *Two women were excluded from analysis because their vaginal samples were considered invalid for detection of HIV-1 RNA. cART, combined antiretroviral treatment; ART, antiretroviral treatment.

Of the 88 women analyzed, vaginal HIV-1 shedding was detected in 9 patients (10%), but the proportion varied from 4% among women on antiretroviral treatment versus 86% among those that were not treated. Clinical, immunological and virological characteristics of the “vaginal HIV-1 shedders” are showed in Table 2. Concerning the relationship between vaginal HIV-1 shedding and PVL, we found that no woman with undetectable PVL had any vaginal HIV-1 shedding. Among vaginal HIV-1 shedders, 4 women (5%) had a vaginal HIV-1 RNA that was 1 logarithm higher than corresponding PVL (Table 2). In all vaginal HIV-1 shedders samples, sequences obtained from plasma and vaginal secretions were identical: 6 resulted wild types, 2 revealed the 103N mutation and 1 the 41L, 101Q and 138A mutations.

Table 2.

Clinical, virological and immunological characteristics of 9 vaginal HIV-1 shedders.

| Vaginal HIV-1 shedders | Vaginal HIV-1 RNA (cp/ml) | Plasma HIV-1 RNA (cp/ml) | Viral sequence (plasma and vagina) | CD4 cell count (cells/mm3) | Time from HIV-1 diagnosis | ART | Months of current ART | STIsa | HR-HPVb | Cervical cytologyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 160 | 52 | Wild type | 479 | 3 months | Dual-therapy | <6 months | Vaginal bacteria and/or fungi | Negative | Negative |

| Patient 2 | 150 | 4400 | K103N | 42 | 25 years | Dual therapy | <6 months | Vaginal bacteria and/or fungi | Missing | Negative |

| Patient 3 | 2200 | 147 | Wild type | 428 | 28 years | cART | ≥6 months | Positive | LSIL | |

| Patient 4 | 4800 | 100000 | Wild type | 49 | 2 months | Not treated | Vaginal bacteria and/or fungi | Negative | Negative | |

| Patient 5 | 850000 | 28000 | K103N | 615 | 1 month | Not treated | Vaginal bacteria and/or fungi | Positive | LSIL | |

| Patient 6 | 660 | 6175000 | M41L, K101Q, E138A | 62 | 1 month | Not treated | Vaginal bacteria and/or fungi; Mycoplasma | Positive | LSIL | |

| Patient 7 | 10000 | 135800 | Wild type | 776 | 15 years | Not treated | HSV-2; Mycoplasma | Negative | LSIL | |

| Patient 8 | 830 | 990000 | Wild type | 98 | 25 years | Not treated | Vaginal bacteria and/or fungi | Positive | HSIL | |

| Patient 9 | 260000 | 28000 | Wild type | 46 | 23 years | Not treated | Vaginal bacteria and/or fungi | Negative | LSIL | |

Notes.

Sexual transmitted infections were investigated collecting vaginal swabs tested for vaginal bacteria, Candida, Trichomonas vaginalis and HSV and cervical swabs tested for Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma and Mycoplasma by PCR.

Detected by Hybrid Capture II.

By Papanicolau smears.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; STIs, sexual transmitted infections; HR-HPV, high risk Human Papillomavirus; LSIL, low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; HSIL, high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

Patients 1–3 are vaginal HV-1 shedders on ART and Patients 4–9 are vaginal HIV-1 shedders not treated. All patients were Caucasian, except patient 7 who was Afo-Caribbean, and they acquired HIV-1 infection through sexual intercourse. All vaginal shedders were tested for Treponema Pallidum Haemoagglutination Assay (TPHA) and resulted negative.

The univariate analysis (Table 1), using the complete set of data, demonstrated that vaginal HIV-1 shedding was significantly associated with PVL, ART, duration of ART and CD4 cell count (p-values, <0.0001 <0.0001, <0.0001 and 0.0493, respectively). No association between exposure category, CDC stage, genital infections, HR-HPV infections, cervical dysplasia, menopause or hysterectomy and vaginal HIV-1 shedding was observed (p-values, >0.05). The univariate significant variables were considered in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, which showed statistical significant effects of the PVL and the antiretroviral treatment on the vaginal HIV-1 shedding (Chi-square: 12.34 and 4.81; p-values: 0.0004 and 0.0284, respectively).

Regarding the 81 women on ART, only 3 (4%) patients were vaginal HIV-1 shedders. Of these vaginal HIV-1 shedders, the totality had detectable HIV-1 RNA also in plasma and 2 had vaginal levels of HIV-1 RNA that were 1 logarithm higher than the corresponding PVL. Among women on ART without vaginal HIV-1 shedding, 71 (88%) women had an undetectable HIV-1 RNA in plasma and 7 (8%) had detectable HIV-1 RNA in plasma. No women virologically suppressed in plasma had HIV-1 RNA detectable in vagina. The univariate analysis carried out in the group of women on ART, showed that the vaginal HIV-1 shedding was significantly associated with detectable PVL (p-value, 0.0253). No significant effect of CD4 cell count, antiretroviral regimen and the other variables on vaginal HIV-1 shedding was observed (p-values >0.05).

Finally, among 7 women without antiretroviral treatment, vaginal HIV-1 shedding was detected in 6 (86%) women, of whom the totality had detectable HIV-1 RNA also in plasma and 2 had vaginal levels of HIV-1 RNA that were 1 logarithm higher than those found in plasma.

In this cross-sectional study, we reported a lower prevalence of vaginal HIV-1 shedding than in the previous studies. Cu-Uvin et al. reported cervico-vaginal HIV-1 RNA shedding in 26% of their HIV-1 infected population.4 An Italian study conducted by Fiore et al. reported cervico-vaginal HIV-1 RNA shedding in all untreated women, 80% of naive patients, 79% of women on non-cART treatment and in 40% of women on cART treatments.7 It is conceivable that these higher rates of cervico-vaginal HIV-1 shedding recovered in the previous studies were due to the use of antiretroviral therapies less effective than those currently available, although it cannot be ruled out that low prevalence of vaginal HIV-1 shedding found might be due to the small sample size of our cohort. Recently, Moreira et al. reported low prevalence of female genital tract HIV-1 shedding (13%) comparable to what found in our study.20 Moreover, Sheth et al. demonstrated that genital tract HIV-1 shedding was uncommon in women on long-term ART, even in the presence of conditions classically reported to increase genital HIV-1 shedding risk.11

In our cohort of HIV-infected women, we found that vaginal HIV-1 shedding was positively correlated with a detectable PVL, in agreement with previous studies.4-7,21-23 Baeten et al. demonstrated that plasma and genital viral load independently predicted female-to-male HIV-1 transmission risk among women not on ART, but importantly PVL was detectable for all patients with undetectable genital viral loads who transmitted HIV-1.24 In our study, we found that vaginal HIV-1 shedding was associated with the PVL and the antiretroviral treatment and these correlations were confirmed to the multivariate analysis. Furthermore, our study suggests that the duration of ART correlates with the suppression of HIV-1 RNA in vagina. Particularly, it was observed that only 1.3% women had positive vaginal HIV-1 shedding at least 6 months of treatment while the corresponding value in no treated woman was 85.7%. Nevertheless, the statistically significant effect of the duration of ART was lost in the multivariate analysis. Among women on treatment, the used regimen (cART vs mono-/dual-therapy) did not exert different effect on vaginal HIV-1 shedding, in contrast with the results of other authors. In fact, Fiore et al. sustained that cART successfully reduced plasma and vaginal viral load, while non-cART regimens were less effective to reduce HIV-1 viral load in vagina.7

The role of high CD4 cell count in reducing the risk of vaginal HIV-1 shedding appeared to be limited and the statistical significance of CD4 cell count was lost in the multivariate analysis. The studies conducted by Kovacs et al. and Fiore et al. reported similar results; in particular, they showed an association between genital HIV-1 shedding and both CD4 cell count and ART.7,23 However, these associations were no longer significant when adjusting for PVL. We speculate that the limited role of CD4 cell count on vaginal HIV-1 shedding could be explained by the immunovirological discordance observed in some HIV-infected patients, especially in late presenters, unable to achieve an increase in CD4 cell count in the context of sustained virological suppression upon starting ART.25 Hence, in our experience, plasma virological suppression was the most important factor for reducing the risk of vaginal HIV-1 shedding.

In this experience the prevalence of genital tract infections was low and no association was documented between any of the tested genital tract infections and vaginal HIV-1 shedding. A low prevalence of genital tract infections was reported also by Cu-Uvin et al.8 Furthermore, some studies conducted among women on ART reported that the association of genital HIV-1 shedding with genital tract infections was not significant.10,11 Respecting HSV-2 infection, it is well established that HSV-2 infection enhanced the risk of genital HIV-1 shedding,10,26 nevertheless it is likely that we have not found any association between HSV-2 infection and vaginal HIV-1 shedding because women did not shade HSV-2 virus the day of visit.

Among women on ART with suppressed PVL, we don't detected vaginal HIV-1 shedding. Except for Cu-Uvin et al. who reported detectable HIV-1 RNA in cervico-vaginal lavage but not in the plasma only in 1% of women,4 other studies reported genital HIV-1 shedding in a considerable percentage of women with undetectable PVL.7,8,10,11,17,23,27 It is conceivable that the differences of prevalence in vaginal HIV-1 shedding observed in our study are partially due to the different methods used for sampling genital secretions. In our study we collected vaginal swabs rolled against posterior fornix of vagina and then we detected HIV-1 RNA on vaginal swabs. Cu-Uvin et al. reported that sampling all genital subcompartments (endocervix, ectocervix and vagina) increased detection of genital HIV-1 shedding compared to sampling a single subcompartment and among women who did shed, intermittent genital HIV-1 shedding was most common than persistent shedding.8 Moreover, sampling both cervico-vaginal lavage and swabs could increase the rate of HIV-1 RNA detection.23 However, our choice of vaginal swab collection was justified firstly by the fact that the swab might be better than cervico-vaginal lavage to detect HIV-1 RNA in genital secretions, because of no dilution of the sample. Secondly, the vagina was the compartment in which genital HIV-1 shedding occurred more commonly according to Graham et al.28 Even in view of these considerations, we are aware that the prevalence of vaginal HIV-1 shedding observed in the present study could be underestimated.

Among women with detectable HIV-1 RNA both in plasma and in vagina, 4/9 patients (44%) had vaginal levels of HIV-1 RNA greater than PVL, but we did not find differences in viral sequences derived from plasma and vagina, in contrast to what reported by other authors.4,29

There are several limitation of our study. First, more numerous cohort of HIV-1 infected women could have allowed for a more efficient univariate and multivariate analysis in both groups of patients on ART and not treated. Second, as previously explained, collecting only one vaginal swab for each patient could have caused underestimation of genital HIV-1 shedding. Moreover, we did not ask women about the menstrual cycle phase, although women with active menstruation were excluded. However, in a recent study Sheth et al. did not find any associations between menstrual cycle phase and genital virus shedding among women on ART.11 Third, we collected only cell-free and not cell-associated virus and analyzed only HIV-1 RNA and not proviral DNA. Fourth, the sample size to detect vaginal HIV-1 shedding was not based on rates in people on ART or on the probability of detecting a difference, taking in to account a possible HIV-1 sample frequency displacement. Moreover, the observed HIV-1 sample frequency displacement had an effect on the size effect estimation (Odd Ratio in this case). All these issues could have an effect on the power to detect shedding and, to avoid providing a wrong message, we had decided not showing the estimated Odd Ratios. Finally, our study was cross-sectional in nature, thus our considerations about the predicting factors of genital viral shedding should be supported by other longitudinal studies.

In 2008 the Swiss Federal Commission for HIV/AIDS suggested that HIV-infected people without sexual transmitted diseases and on suppressive ART for more than 6 months do not transmit HIV.30

Despite that, for several years scientists kept on recommending clinicians caution when using PVL as predictor of infectivity of genital secretions and thus as surrogate measure of HIV transmission risk. More recently, HPTN 052 and the still ongoing Partner Study demonstrated that effective ART, associated with the stable suppression of PVL, could actually suppress the risk of HIV transmission.31,32 Our study joins in this debate. It shows not only a strong association between HIV-1 RNA in plasma and in vagina and a low prevalence of vaginal HIV-1 shedding in women on ART, but, above all, no viral vaginal shedding in plasma suppressed women. Thus, it gives strong support to the fact that PVL is the most important predicting factor of vaginal HIV-1 shedding. The use of ART for at least 6 months with the achievement of stable suppressed PVL and the resulting abolition of vaginal HIV-1 shedding may thus be considered an efficient method for the prevention of HIV genital transmission.

Abbreviations

- ART

antiretroviral treatment

- ASCUS

atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

- cART

Combined antiretroviral therapy

- CDC

Center for Disease Control

- HCII

Hybrid Capture II HPV

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- HR-HPV

high risk Human Papillomavirus

- HSIL

high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- HSV-2

Herpes Simplex Virus type 2

- INSTI

integrase strand transfer inhibitor

- LSIL

low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- MCV

maraviroc

- NNRTI

non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- NRTI

nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

- Pap

Papaniculaou

- PI

protease inhibitors

- TPHA

Treponema Pallidum Haemoagglutination Assay

- PVL

plasma viral load

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all HIV-1 infected women who participated in the study and medical and nursing staff at Infectious Diseases Division and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, IRCCS San Martino-IST, Genoa. The authors also wish to thank Dr. Renata Barresi, Dr. Paola Canepa and the staff at Hygiene Service for the important technical support in the laboratory testing.

References

- [1].Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, Serwadda D, Li C, Wabwire-Mangen F, Meehan MO, Lutalo T, Gray RH. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med 2000; 342(13):921-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mofenson LM, Lambert JS, Stiehm ER, Bethel J, Meyer WA 3rd, Whitehouse J, Moye J Jr, Reichelderfer P, Harris DR, Fowler MG, et al.. Risk factors for perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in women treated with zidovudine. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 185 Team. N Engl J Med 1999; 341(6):385-93; PMID:10432323; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJM199908053410601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kalichman S, Di Berto G, Eaton L. Human immunodeficiency virus viral load in blood plasma and semen: review and implications of empirical findings. Sexually Transm Dis 2008; 35:55-60; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318141fe9b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cu-Uvin S, Caliendo AM, Reinert S, Chang A, Juliano-Remollino C, Flanigan TP, Mayer KH, Carpenter CC. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on cervico-vaginal HIV-1 RNA. AIDS 2000; 14(4):415-21; PMID:10770544; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tanton C, Weiss HA, Le Goff J, Changalucha J, Rusizoka M, Baisley K, Everett D, Ross DA, Belec L, Hayes RJ, et al.. Correlates of HIV-1 genital shedding in Tanzanian women. PLoS One 2011; 6(3):e17480; PMID:21390251; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0017480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Alcaide ML, Chisembele M, Malupande E, Arheart K, Fischl M, Jones DL. A cross-sectional study of bacterial vaginosis, intravaginal practices and HIV genital shedding; implications for HIV transmission and women's health. BMJ Open 2015; 5(11):e009036; PMID:26553833; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fiore JR, Suligoi B, Saracino A, Di Stefano M, Bugarini R, Lepera A, Favia A, Monno L, Angarano G, Pastore G. Correlates of HIV-1 shedding in cervico-vaginal secretions and effects of antiretroviral therapies. AIDS 2003; 17(15):2169-76; PMID:14523273; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00002030-200310170-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cu-Uvin S, DeLong AK, Venkatesh KK, Hogan JW, Ingersoll J, Kurpewski J, De Pasquale MP, D'Aquila R, Caliendo AM. Genital tract HIV-1 RNA shedding among women with below detectable plasma viral load. AIDS 2010; 24(16):2489-97; PMID:20736815; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833e5043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Homans J, Christensen S, Stiller T, Wang CH, Mack W, Anastos K, Minkoff H, Young M, Greenblatt R, Cohen M, et al.. Permissive and protective factors associated with presence, level, and longitudinal pattern of cervico-vaginal HIV shedding. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 60(1):99-110; PMID:22517416; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824aeaaa [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Low AJ, Konate I, Nagot N, Weiss HA, Kania D, Vickerman P, Segondy M, Mabey D, Pillay D, Meda N, et al.. Cervico-vaginal HIV-1 shedding in women taking antiretroviral therapy in Burkina Faso: a longitudinal study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 65(2):237-45; PMID:24226060; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sheth AN, Evans-Strickfaden T, Haaland R, Martin A, Gatcliffe C, Adesoye A, Omondi MW, Lupo LD, Danavall D, Easley K, et al.. HIV-1 genital shedding is suppressed in the setting of high genital antiretroviral drug concentrations throughout the menstrual cycle. J Infect Dis 2014; 210(5):736-44; PMID:24643223; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/infdis/jiu166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Coombs RW, Reichelderfer PS, Landay AL. Recent observations on HIV type-1 infection in the genital tract of men and women. AIDS 2003; 17(4):455-80; PMID:12598766; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00002030-200303070-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Else LJ, Taylor S, Back DJ, Khoo SH. Pharmacokinetics of antiretroviral drugs in anatomical sanctuary sites: the male and female genital tract. Antivir Ther 2011; 16(8):1149-67; PMID:22155899; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3851/IMP1919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wang CC, McClelland RS, Reilly M, Overbaugh J, Emery SR, Mandaliya K, Chohan B, Ndinya-Achola J, Bwayo J, Kreiss JK. The effect of treatment of vaginal infections on shedding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis 2001; 183(7):1017-22; PMID:11237825; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/319287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mostad SB, Overbaugh J, DeVange DM, Welch MJ, Chohan B, Mandaliya K, Nyange P, Martin HL Jr, Ndinya-Achola J, Bwayo JJ, et al.. Hormonal contraception, vitamin A deficiency, and other risk factors for shedding of HIV-1 infected cells from the cervix and vagina. Lancet 1997; 350(9082):922-7; PMID:9314871; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Clemetson DB, Moss GB, Willerford DM, Hensel M, Emonyi W, Holmes KK, Plummer F, Ndinya-Achola J, Roberts PL, Hillier S, et al.. Detection of HIV DNA in cervical and vaginal secretions. Prevalence and correlates among women in Nairobi, Kenya. JAMA 1993; 269(22):2860-4; PMID:8497089; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/jama.1993.03500220046024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bunupuradah T, Bowonwattanuwong C, Jirajariyavej S, Munsakul W, Klinbuayaem V, Sophonphan J, Mahanontharit A, Hirschel B, Ruxrungtham K, Ananworanich J; HIV STAR Study team . HIV-1 genital shedding in HIV-infected patients randomized to second-line lopinavir/ritonavir monotherapy versus tenofovir/lamivudine/lopinavir/ritonavir. Antivir Ther 2014; 19(6):579-86; PMID:24464590; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3851/IMP2737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O'Connor D, Prey M, Raab S, Sherman M, Wilbur D, Wright T Jr, et al.. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA 2002; 287(16):2114-9; PMID:11966386; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/jama.287.16.2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].R Core Team (2013) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria: Available at http://www.R-project.org (Accessed on: November12, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- [20].Moreira C, Venkatesh KK, DeLong A, Liu T, Kurpewski J, Ingersoll J, Caliendo AM, Cu-Uvin S. Effect of treatment of asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis on HIV-1 shedding in the genital tract among women on antiretroviral therapy: a pilot study. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49(6):991-2; PMID:19694541; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/605540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Uvin SC, Caliendo AM. Cervico-vaginal human immunodeficiency virus secretion and plasma viral load in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive women. Obstet Gynecol 1997; 90(5):739-43; PMID:9351756; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00411-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hart CE, Lennox JL, Pratt-Palmore M, Wright TC, Schinazi RF, Evans-Strickfaden T, Bush TJ, Schnell C, Conley LJ, Clancy KA, et al.. Correlation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA levels in blood and the female genital tract. J Infect Dis 1999; 179(4):871-82; PMID:10068582; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/314656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kovacs A, Wasserman SS, Burns D, Wright DJ, Cohn J, Landay A, Weber K, Cohen M, Levine A, Minkoff H, et al.. Determinants of HIV-1 shedding in the genital tract of women. Lancet 2001; 358(9293):1593-601; PMID:11716886; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06653-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Baeten JM, Kahle E, Lingappa JR, Coombs RW, Delany-Moretlwe S, Nakku-Joloba E, Mugo NR, Wald A, Corey L, Donnell D, et al. Partners in Prevention HSV/HIV Transmission Study Team . Genital HIV-1 RNA predicts risk of heterosexual HIV-1 transmission. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3(77):77ra29; PMID:21471433; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tan R, Westfall AO, Willig JH, Mugavero MJ, Saag MS, Kaslow RA, Kempf MC. Clinical outcome of HIV-infected antiretroviral-naive patients with discordant immunologic and virologic responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 47(5):553-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Buve A, Jespers V, Crucitti T, Fichorova RN. The vaginal microbiota and susceptibility to HIV. AIDS 2014; 28(16):2333-44; PMID:25389548; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Venkatesh KK, DeLong AK, Kantor R, Chapman S, Ingersoll J, Kurpewski J, De Pasquale MP, D'Aquila R, Caliendo AM, Cu-Uvin S. Persistent genital tract HIV-1 RNA shedding after change in treatment regimens in antiretroviral-experienced women with detectable plasma viral load. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013; 22(4):330-8; PMID:23531097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Graham SM, Masese L, Gitau R, Jalalian-Lechak Z, Richardson BA, Peshu N, Mandaliya K, Kiarie JN, Jaoko W, Ndinya-Achola J, et al.. Antiretroviral adherence and development of drug resistance are the strongest predictors of genital HIV-1 shedding among women initiating treatment. J Infect Dis 2010; 202(10):1538-42; PMID:20923373; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/656790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].De Pasquale MP, Leigh Brown AJ, Uvin SC, Allega-Ingersoll J, Caliendo AM, Sutton L, Donahue S, D'Aquila RT. Differences in HIV-1 pol sequences from female genital tract and blood during antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003; 34(1):37-44; PMID:14501791; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00126334-200309010-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Pearshouse R. Switzerland: statement on sexual transmission of HIV by people on ART. HIV AIDS Policy Law Rev 2008; 13(1):37-8; PMID:18727190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Hakim JG, Kumwenda J, Grinsztejn B, Pilotto JH, et al.. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011; 365(6):493-505; PMID:21767103; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rodger A, Bruun T, Cambiano V, Vernazza P, Estrada V, Lunzen JV, et al.. HIV Transmission Risk Through Condomless Sex If HIV+ Partner On Suppressive ART: PARTNER Study. [Abstract] 153LB at CROI 2015. [Google Scholar]