Abstract

A brain network comprising the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and amygdala plays important roles in developmentally regulated cognitive and emotional processes. However, very little is known about the maturation of mPFC-amygdala circuitry. We conducted anatomical tracing of mPFC projections and optogenetic interrogation of their synaptic connections with neurons in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) at neonatal to adult developmental stages in mice. Results indicate that mPFC-BLA projections exhibit delayed emergence relative to other mPFC pathways and establish synaptic transmission with BLA excitatory and inhibitory neurons in late infancy, events that coincide with a massive increase in overall synaptic drive. During subsequent adolescence, mPFC-BLA circuits are further modified by excitatory synaptic strengthening as well as a transient surge in feedforward inhibition. The latter was correlated with increased spontaneous inhibitory currents in excitatory neurons, suggesting that mPFC-BLA circuit maturation culminates in a period of exuberant GABAergic transmission. These findings establish a time course for the onset and refinement of mPFC-BLA transmission and point to potential sensitive periods in the development of this critical network.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Human mPFC-amygdala functional connectivity is developmentally regulated and figures prominently in numerous psychiatric disorders with a high incidence of adolescent onset. However, it remains unclear when synaptic connections between these structures emerge or how their properties change with age. Our work establishes developmental windows and cellular substrates for synapse maturation in this pathway involving both excitatory and inhibitory circuits. The engagement of these substrates by early life experience may support the ontogeny of fundamental behaviors but could also lead to inappropriate circuit refinement and psychopathology in adverse situations.

Keywords: adolescence, amygdala, prefrontal development

Introduction

The transition from infancy to adulthood marks the ontogenesis of fundamental behavioral processes, such as threat learning (Rudy, 1993; Richardson et al., 2000; Akers et al., 2012; Deal et al., 2016), social interaction (Panksepp, 1981; Vanderschuren et al., 1997), and aggression (Pellis et al., 1992; Pellis and Pasztor, 1999). On the other hand, this period is also characterized by a peak incidence of the majority of psychiatric disorders (Kessler et al., 2005). It is currently estimated that 1 in 5 adolescents will develop such a condition that persists into adulthood, with the experience of early life stress being a significant risk factor (Brenhouse and Andersen, 2011). Among the brain regions most highly implicated in these conditions are the mPFC and amygdala, which are crucial regulators of the stress response (McEwen et al., 2012). Well into adolescence, these regions display a variety of molecular, anatomical, and synaptic changes, prompting the suggestion that they may require a protracted period of maturation that may be influenced by both genetics and experience (Kagan and Snidman, 1991; Blakemore and Choudhury, 2006; DeRubeis et al., 2008; Paus et al., 2008). However, it remains unclear how the maturation of specific synaptic pathways involving these regions unfolds over the course of early development.

Of particular significance in the function of these networks are synaptic connections between mPFC and the basolateral division of amygdala (BLA) (Cho et al., 2013; Little and Carter, 2013; Arruda-Carvalho and Clem, 2014, 2015; Hübner et al., 2014). Human studies indicate that mPFC-amygdala functional connectivity exhibits reorganization during adolescent development (Gee et al., 2013), and is abnormal in subjects with depression (Carballedo et al., 2011; Perlman et al., 2012), schizophrenia (Liu et al., 2014), bipolar (Passarotti et al., 2012; Anticevic et al., 2013), and anxiety disorders (Kessler et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2014). Anatomical projections from mPFC to BLA have been most extensively examined in rodents using tracing reagents, such as fluorescent dyes (Cassell et al., 1989; Bouwmeester et al., 2002a) and lectins (Mcdonald et al., 1996; Gabbott et al., 2005), with results indicating that all major subdivisions of the mPFC convey axon fibers to the BLA. However, early postnatal analysis of this innervation has been limited to one study in rats, which inferred that mPFC projections arrive between the second and third postnatal week based on retrograde transport of lipophilic tracer from the BLA (Bouwmeester et al., 2002a). To better elucidate the development of this circuitry, it would be valuable not only to directly visualize mPFC axons in very young animals, but also to examine the establishment and refinement of their functional transmission onto BLA neurons. We therefore used a viral optogenetic approach in mice to specifically label mPFC glutamatergic projections and systematically interrogate mPFC-BLA transmission over the course of neonatal to adult development.

Materials and Methods

Subjects.

All subjects were male C57BL/6J mice aged postnatal day (P) 3–53 at the time of surgery. Animals were kept with the dam until weaning and housed in groups of 3–5 following weaning on a 12 h light/dark cycle and given food and water ad libitum. All manipulations were approved in advance by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Stereotaxic surgery.

Mice were anesthetized through hypothermia (P3 animals) or a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (P8 and older), and mounted in a stereotaxic frame (Stoelting) as described previously (Arruda-Carvalho and Clem, 2014). A small volume of AAV1.CaMKIIa.hChR2(H134R)-eYFP.WPRE.hGH virus (Penn Vector Core, RRID:SCR_010038) was injected into mPFC (P3: AP 0.5, ML ±0.1, DV −0.9; P8: AP 1.2, ML ±0.3, DV −1.3; P14: AP 1.4, ML ±0.3, DV −1.6; P23 AP 1.7, ML ±0.3, DV −2; P38 and P53: AP 1.9, ML ±0.3, DV −2.2) bilaterally by way of a motorized microsyringe using the same procedure as in our previous work (Arruda-Carvalho and Clem, 2014). Animals underwent surgery at P3, P8, P14, P23, P38, and P53. Litters were spread across time points to exclude nonspecific effects of parental care. To compensate for age-dependent changes in cortical volume, we made proportional adjustments to the volume of injected virus as follows: 0.15 μl for P3, 0.2 μl for P8, 0.25 μl for P14, 0.3 μl for P23, and 0.4 μl for P38 and older animals. Mice recovered in their homecages for 7 d until further manipulation. For infant experiments (P10 and P15) subjects were closely monitored following surgery and were excluded from analysis if they did not exhibit normal developmental weight gain. All subjects were weaned at P21-P24 and housed in groups of 3–5.

Immunohistochemistry and imaging.

Mice were perfused transcardially with PBS (0.1 m) and 4% PFA. Brains were removed, fixed overnight in 4% PFA, and transferred to 0.1 m PBS. Coronal sections (50 μm) were cut using a VT1200S vibratome (Leica). Sections were incubated for 48 h. with goat polyclonal anti-PSD95 (1:200; Abcam catalog #ab12093, RRID:AB_298846) and then for 2 h at room temperature with AlexaFluor-555-conjugated donkey anti-goat secondary antibody (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific catalog #A21432, RRID:AB_10053826). Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) was used as a nuclear dye. Sections were mounted on slides with Permafluor antifade medium (Thermo Scientific). All images were acquired using a confocal (LSM 780; Zeiss) microscope. For estimation of EYFP infection and mPFC volumes the Cavalieri method was applied, in which estimated volume Vc = d (Σ (yi)), d = distance between sections, and y = area of EYFP or mPFC per section. Area measurements were performed by contouring regions of interest in ImageJ for all sections containing mPFC at a slice interval of 250 μm (every fifth section at 50 μm thickness). mPFC was defined as areas anterior cingulate (Cg1), prelimbic (PL), infralimbic (IL) and dorsal peduncular cortices (DP) extending from the caudal border of the main olfactory bulb to the genu of the corpus callosum. EYFP expression was delineated by application of a uniform threshold function in ImageJ. The percentage EYFP infection of each mPFC subregion was calculated as the estimated volume EYFP/volume mPFC subregion for individual animals. Quantification of projection-associated EYFP fluorescence was performed on confocal images by calculating average pixel intensity in the anterior basal nucleus of the BLA of both hemispheres in 3–6 coronal slices (50 μm thickness) per animal. As an internal baseline for each section, intensity measurements were obtained from the adjacent lateral nucleus of the BLA, which is relatively devoid of mPFC projections (Cho et al., 2013; Arruda-Carvalho and Clem, 2014; Hübner et al., 2014). These baseline measures were subtracted from those obtained in the basal nucleus before comparison of EYFP fluorescence across ages. We attempted to colocalize EYFP terminals with PSD95 as a measure of anatomical synapse size and density across development (Dumitriu et al., 2012). However, spurious overlap between EYFP and PSD95 precluded such analysis. We nevertheless presented PSD95 labeling to provide some contrast in our BLA images because no other counterstain was included.

Slice electrophysiology.

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused transcardially with ice-cold (0°C–4°C) sucrose solution composed of (in mm): 210.3 sucrose, 11 glucose, 2.5 KCl, 1 NaH2PO4, 26.2 NaHCO3, 0.5 ascorbate, 0.5 CaCl2, and 4 MgCl2. Acute 350 μm coronal slices of BLA were obtained from dissected brains from a VT1200S vibratome (Leica) and then incubated at 35°C for 40 min in the same solution, but with reduced sucrose (105.2 mm) and addition of NaCl (109.5 mm). Following recovery, slices were maintained at room temperature in standard ACSF composed of (in mm) as follows: 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 NaH2PO4, 26.2 NaHCO3, 11 glucose, 2 CaCl2, and 2 MgCl2. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were obtained from principal projections neurons in basal amygdala using borosilicate glass electrodes (3–5 mΩ). Electrode internal solution was composed of (in mm) the following: 130 Cs-methanesulfonate, 10 HEPES, 0.5 EGTA, 8 NaCl, 4 Mg-ATP, 1 QX-314, 10 Na-phosphocreatine, and 0.4 Na-GTP. Principal excitatory neurons in the anterior basal nucleus were discriminated on the basis of large soma size, high capacitance (>200 pF), and slow EPSC kinetics, under the rationale that no interneuron subtypes possess all three of these characteristics. mPFC axon terminals were stimulated using TTL-pulsed microscope objective-coupled light-emitting diodes (LEDs, 460 nm, 20 mW/mm2, Prizmatix). This pulse intensity evoked maximal response amplitudes at all ages. For analysis of AMPA/NMDA ratios, we applied 1 μm TTX (Abcam) and 100 μm (Abcam) for more stringent isolation of monosynaptic transmission as previously described (Cruikshank et al., 2010; Arruda-Carvalho and Clem, 2014). Paired-pulse evoked EPSC, spontaneous EPSCs and IPSCs, and evoked IPSC/EPSC analyses were conducted in standard ACSF described above. Data were low-pass filtered at 3 kHz (evoked) and 10 kHz (spontaneous) and acquired at 10 kHz using Multiclamp 700B and pClamp 10 (Molecular Devices). All stimulation was conducted at 0.1 Hz to avoid inducing synaptic plasticity. Series and membrane resistance was continuously monitored, and recordings were discarded when these measurements changed by >20%. Recordings in which series resistance exceeded 25 mΩ were rejected. Detection and analysis of sEPSCs and sIPSCs were performed blind to experimental group using MiniAnalysis (Synaptosoft). EPSC decay time constants (τ decay) were obtained by standard exponential curve fitting of averaged current traces in Clampfit (Molecular Devices). AMPA/NMDA ratio was calculated as the peak EPSC at −70 mV divided by the EPSC amplitude at 100 ms after current onset at 40 mV (Arruda-Carvalho and Clem, 2014). Rectification of AMPAR-EPSCs was quantified by measuring EPSC amplitude at 8 holding potentials between −70 and 50 mV in the presence of the NMDAR antagonist CPP (10 μm) and internal spermine (100 μm), and calculating a rectification index as the slope at negative potentials (−70 through 0 mV) divided by the slope at positive potentials (0 through 50 mV).

Statistics.

Data are presented as mean ± SE, with n shown as the number of animals for histological experiments, or number of cells followed by number of animals in parentheses for electrophysiological experiments, in associated figure legends. Statistical comparisons were obtained in Graphpad Prism through one-way ANOVA or two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, where appropriate. Omnibus test results (F values) are reported in the text. To test for group differences following ANOVA, we applied the software default of Tukey's or Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests for all pairwise comparisons following nonrepeating and repeating measures ANOVA, respectively, and significant results were denoted by asterisks in associated figures.

Results

To investigate changes in synaptic transmission within the mPFC-BLA pathway over development, we sought to use viral technology for expression of CaMKII-promoter-driven, EYFP-tagged channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) in mPFC neurons. To this end, we identified a specific serotype of adeno-associated virus (AAV-1) that drives ChR2 accumulation in synaptic terminals within 4 d of infection, making it suitable for narrow experimental time windows imposed by such a study. We chose six time points for synaptic interrogations spanning the neonatal to late adolescent/adult stages: P10, P15, P21, P30, P45, and P60 in C57BL/6J mice. To control for potential effects of viral expression time on synaptic physiology, however, all virus infusions were performed 7 d before these investigations. To prohibit litter effects on projection anatomy and physiology, litters were pseudo-randomly distributed across age groups.

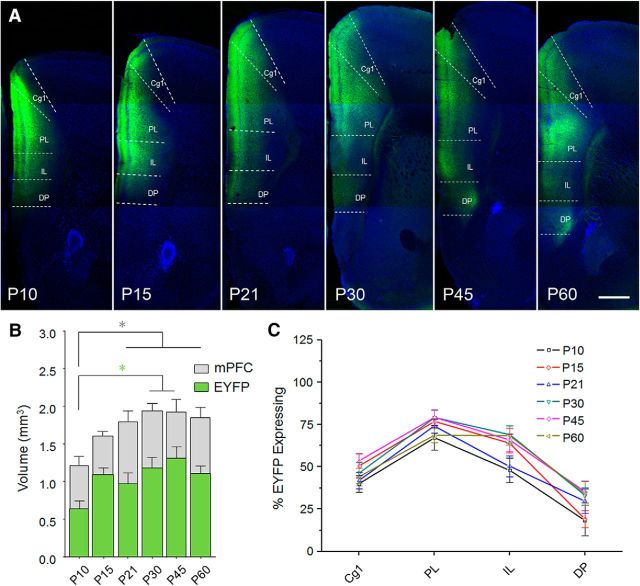

Although excitatory neurogenesis is completed at birth (Levers et al., 2001), neocortical volume increases during postnatal development due largely to the growth of neuropil. This was an important consideration in our viral infusions because region selectivity requires lower viral spread in neonates compared with adults. Therefore, we first determined the injected volume of AAV1-ChR2-EYFP required for mPFC transduction in adult mice (P60) while largely avoiding spread into adjacent structures. We then calculated linear adjustments of this volume based on neocortical size across development (Zhang et al., 2005) and performed size-adjusted injections at the following postnatal (P) days: P3, P8, P14, P23, P38, and P53. Seven days later, we used the Cavalieri method to estimate the spread of viral expression as well as the volume of mPFC, defined as cingulate cortex area 1 (Cg1), prelimbic (PL), infralimbic (IL) and dorsal peduncular cortex (DP), extending from the caudal border of the main olfactory bulb to the genu of the corpus callosum (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001) (Fig. 1A). As expected, resulting viral spread was more restricted at the earliest age (P10) (one-way ANOVA, F(5,55) = 3.22, p = 0.013; Fig. 1B), which also exhibited lower mPFC volume compared with later ages (one-way ANOVA, F(5,55) = 4.71, p = 0.0012; Fig. 1C). To compare how viral expression was distributed across mPFC, we quantified the percentage volume of each mPFC subregion containing EYFP and subjected the results to a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA. This revealed a main effect of region (F(3,55) = 108.3, p < 0.0001), but no effect of age (F(5,55) = 1.70, p = 0.15) and no interaction between region and age (F(15,55) = 1.23, p = 0.26). These results confirm that adjustment for brain size effectively normalized regional infection levels across ages.

Figure 1.

Volume estimation of prefrontal channelrhodopsin expression. A, Representative confocal images of prefrontal sections containing target site at postnatal age of death. Subjects received stereotaxic injections of AAV1-CaMKII-ChR2(H134R)-EYFP 7 d before perfusion and brain sectioning. Sections were stained with Hoechst nuclear dye before imaging EYFP intrinsic fluorescence. Scale bar, 500 μm. Cavalieri volume estimation was based on the area of EYFP and mPFC (B) contained in every fifth section at 50 μm thickness as described in Materials and Methods. mPFC was defined as Cg1, PL, IL, and DP extending from the caudal edge of the main olfactory bulb to the genu of corpus callosum. As expected, both EYFP and mPFC volume exhibited age-dependent increase. Tukey's post hoc test was conducted on all pairwise comparisons following one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05. C, Percentage infection of each mPFC subregion was calculated by dividing EYFP volume by the volume of the structure in which it was contained. P10, n = 9 mice; P15, n = 11 mice; P21, n = 11 mice; P30, n = 11 mice; P45, n = 10 mice; P60, n = 9 mice.

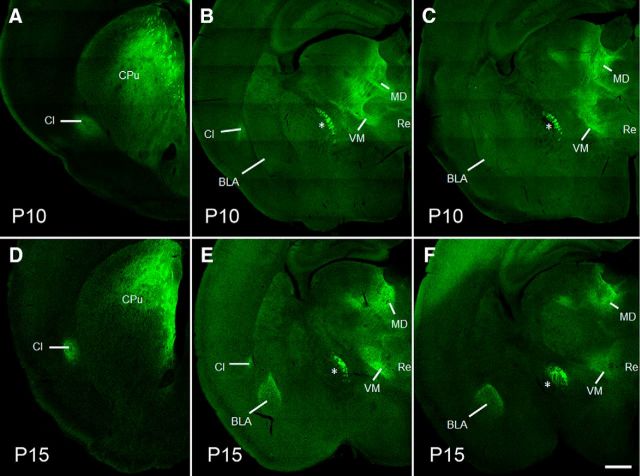

We next examined posterior brain sections for evidence of EYFP in mPFC axon projections. At P10, there was already abundant fluorescence in structures known to contain mPFC fibers and axon terminals in adults (Sesack et al., 1989; Vertes, 2002; Xu and Südhof, 2013), including the septohippocampal nucleus, caudate-putamen, claustrum, mediodorsal, and ventromedial thalamus, and nucleus reuniens (Fig. 2A–C). Conspicuously devoid of fluorescence at this age, however, was the BLA. In comparison, EYFP expression was quite prominent in the BLA at P15. These data confirm that 7 d is sufficient to accumulate ChR2-EYFP in mPFC downstream targets, and suggest the innervation of BLA by mPFC is delayed relative to nearby subcortical structures.

Figure 2.

Delayed emergence of mPFC-BLA projections. Representative images containing EYFP-positive projections were collected by confocal scanning microscopy. At P10, mPFC projections were observed in caudate-putamen (CPu) (A), claustrum (Cl) (A, B), mediodorsal (MD), and ventromedial (VM) thalamus (B, C), and nucleus reuniens (Re) (C), but BLA fluorescence was indiscernible in the same animals (B, C). At P15, EYFP-positive projections could be seen in the BLA in addition to the above structures (D–F). *Previously identified mPFC fiber tract (Xu and Südhof, 2013). Scale bar, 400 μm.

To compare BLA terminal expression across development, we performed confocal microscopy to reveal fine processes containing EYFP that are indicative of mPFC axon fibers. As we had previously observed following mPFC targeting in adult mice (Arruda-Carvalho and Clem, 2014), fluorescence was largely restricted to the anterior division of the basal amygdala; and although the intensity of labeling increased over development, this topography exhibited no appreciable change. High-power images revealed few axons could be seen at P10, but by P15 this gave way to a dense thicket of fibers (Fig. 2A–F). A further increase in density could be observed at later ages. Quantification of integrated fluorescence for all animals that received viral infusions into mPFC (Fig. 1) confirmed a sharp increase in EYFP over background between P10 and P15, followed by additional enhancement of signal at P30 and P45 (one-way ANOVA, F(5,56) = 12.84, p < 0.0001; Fig. 3G), suggesting that mPFC axons continue to proliferate after their abrupt emergence.

Figure 3.

Age-dependent proliferation of mPFC axons in the BLA. A–F, High-power confocal images were obtained across ages to confirm the presence of EYFP-positive fibers. Within the BLA, fluorescence was mostly restricted to the anterior basal amygdala (BA), and was hardly discernible in the lateral (LA), central, and basomedial nuclei at any age. Immunofluorescent labeling of PSD95 (red) is used strictly as contrast. Scale bars: Top, 400 μm; Bottom, 50 μm. BLA was almost entirely devoid of EYFP-positive fibers at P10 (A). However, by P15, mPFC projections had densely ramified within the anterior BA (B). G, A comparison of integrated fluorescence intensity for all animals confirmed that EYFP labeling had an abrupt onset between P10 and P15 and continued to increase until up to P30 in the anterior BA. Background fluorescence was measured in the LA and subtracted from BA fluorescence for each brain section. Tukey's post hoc test was conducted on all pairwise comparisons following one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05. ***p < 0.001. Analysis of mPFC infection spread and BLA fluorescence was performed on the same animals, with n values reported in Figure 1.

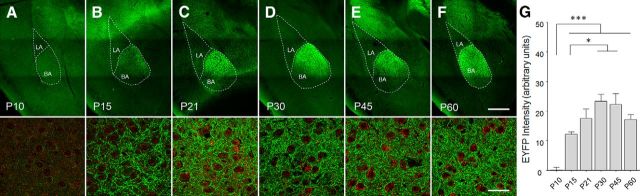

Considering the temporal dynamics of mPFC axon arrival and potential terminal formation, we wondered how this timing relates to ongoing maturation of BLA synaptic transmission. Representation and association of stimuli in BLA are thought to be mediated by principal glutamatergic neurons, which are known as magnocellular neurons in the anterior nucleus and are the most abundant cell type. We therefore targeted these cells for patch-clamp electrophysiology in acute brain slices based on their pyramidal morphology, large size, and high membrane capacitance. To measure global synaptic transmission, we examined spontaneous excitatory (sEPSCs) and IPSCs (sIPSCs), which were specifically isolated from the same neurons by exploiting the reversal potentials of glutamate and GABA receptors (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Development of spontaneous synaptic transmission in the anterior basal nucleus. A, sEPSCs and sIPSCs were obtained from principal excitatory neurons in the anterior basal nucleus of the BLA in acute brain slices. To enable within-cell comparisons of excitatory and inhibitory transmission, sEPSCs and sIPSCs were sampled from the same neuron by clamping the cell at reversal potential for IPSCs (−60 mV) or EPSCs (0 mV), respectively, in a low-chloride internal solution. B, C, Increase in the frequency (B) but not amplitude (C) of sEPSCs between P10 and later ages. Tukey's post hoc test was conducted on all pairwise comparisons following one-way ANOVA. #p < 0.10. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. P10, n = 14 cells (2 mice); P15, n = 15 cells (7 mice); P21, n = 9 cells (4 mice); P30, n = 13 cells (8 mice); P45, n = 8 cells (4 mice); P60, n = 8 cells (6 mice). D, E, Increase in the frequency (D) and amplitude (E) between P10 and later ages, as well as further increase in frequency between P15 and P30. Tukey's post hoc test was conducted on all pairwise comparisons following one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05. ***p < 0.001. F, Decrease in IPSC decay time constant between P10 and later ages. Tukey's post hoc test was conducted on all pairwise comparisons following one-way ANOVA. ****p < 0.0001. P10, n = 15 cells (2 mice); P15, n = 16 cells (7 mice); P21, n = 9 cells (4 mice); P30, n = 14 cells (8 mice); P45, n = 10 cells (5 mice); P60, n = 9 cells (7 mice). G, Cell-by-cell comparison of sEPSC (E) and sIPSC frequency (I) illustrating developmental shift to dominance by spontaneous inhibition. P10, n = 11 cells (2 mice); P15, n = 12 cells (7 mice); P21, n = 7 cells (4 mice); P30, n = 12 cells (8 mice); P45, n = 8 cells (4 mice); P60, n = 7 cells (5 mice). H, Normalized frequency of inhibition (calculated by subtracting sEPSC from sIPSC frequency for individual neurons) illustrating a surge in relative inhibitory drive at P30. Tukey's post hoc comparison was conducted on all pairwise comparisons following one-way ANOVA. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. P10, n = 11 cells (2 mice); P15, n = 12 cells (7 mice); P21, n = 7 cells (4 mice); P30, n = 12 cells (8 mice); P45, n = 8 cells (4 mice); P60, n = 7 cells (7 mice).

Interestingly, we found that the arrival of significant numbers of mPFC fibers at P15 (Fig. 3B) coincides with an abrupt and sustained increase in sEPSC frequency (one-way ANOVA, F(5.61) = 4.17, p = 0.0025; Fig. 4B). However, sEPSC amplitude did not change across development (Fig. 4C). A similar, dramatic increase in sIPSC frequency occurred at P15, but this was followed by further increase up to P30 (one-way ANOVA, F(5.67) = 21.01, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4D). In addition, there was a somewhat weaker increase in amplitude (one-way ANOVA, F(5.67) = 2.981, p = 0.0173; Fig. 4E) as well as a decrease in the decay time of sIPSCs at P15 (one-way ANOVA, F(5.67) = 23.68, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4F), which could potentially reflect the formation of proximal somatic inhibitory synapses or a change in the stoichiometry of GABA receptors (Ehrlich et al., 2013; Bosch and Ehrlich, 2015). Within individual neurons transmission became progressively dominated by sIPSCs at P15 (Fig. 4G), with the difference between sIPSC and sEPSC frequency reaching a peak at P30 (one-way ANOVA, F(5.51) = 13.34, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4H). These data suggest that, although the sharpest increase in both excitatory and inhibitory synapse activity occurs at approximately P15, inhibitory transmission undergoes further enhancement in adolescence.

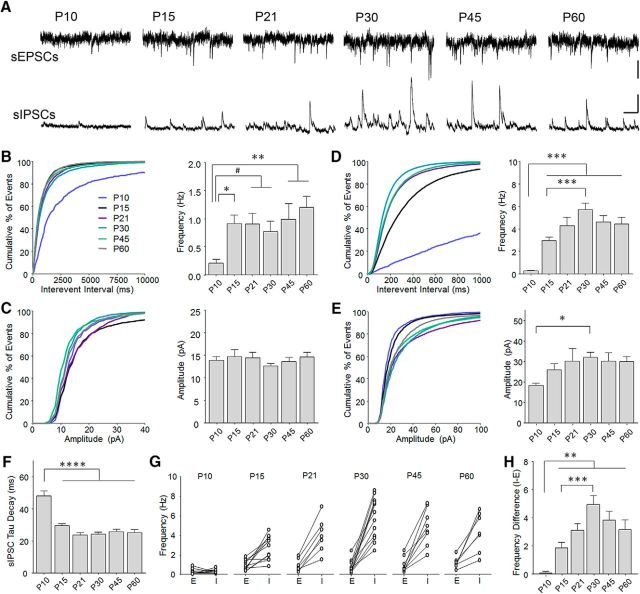

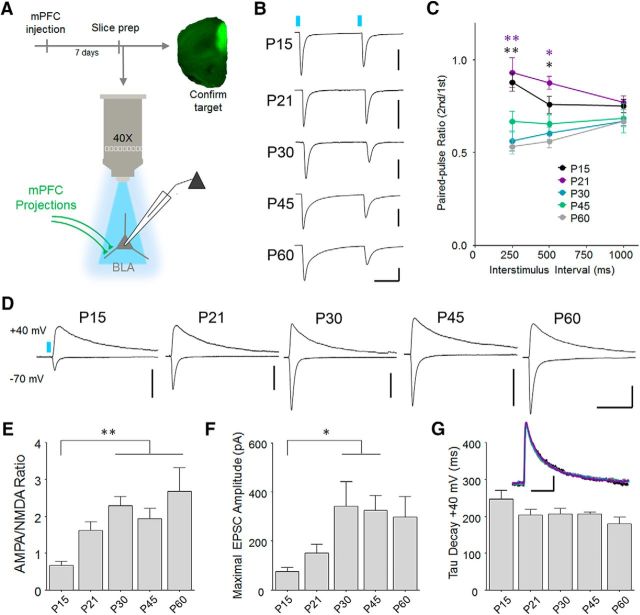

The above data indicate that the development of mPFC projections occurs against a backdrop of dramatic changes in BLA synaptic activity. However, to determine how development specifically affects transmission at mPFC-BLA synapses, we recorded EPSCs during stimulation of mPFC projections using brief pulses from objective-coupled LEDs (460 nm) (Fig. 5A), as we previously performed using ChR2-EYFP in adult mice (Arruda-Carvalho and Clem, 2014). Importantly, we used a pulse intensity (20 mW/mm2) that evoked maximal response amplitudes at all ages. Consistent with the relative absence of mPFC projections at P10, no responses were observed at this age (54 cells/14 animals). However, at later ages, 100% of neurons exhibited synaptic responses to terminal stimulation, suggesting nonselective targeting of principal neurons by these afferents throughout development. To assess how development affects glutamate release at these connections, we analyzed EPSCs during paired-pulse stimulation, in which the relative amplitude of the second response is determined by initial release probability. This revealed an interaction between interstimulus interval and age (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, F(8,112) = 7.04, p < 0.0001; Fig. 5B), consistent with developmental regulation of release dynamics. Follow-up comparisons established that both P15 and P21 animals exhibited higher paired-pulse ratios than older animals, likely indicating that a shift toward higher release probability occurs at these synapses between P21 and P30.

Figure 5.

Developmental strengthening of BLA excitatory synapses formed by mPFC projections. A, Summary of experimental procedure. At 7 d after stereotaxic viral infusions, acute brain slices containing the amygdala were obtained for synaptic physiology. Prefrontal tissue was retained and subsectioned to confirm target expression. Monosynaptic EPSCs were recorded from principal excitatory neurons in the anterior basal nucleus during stimulation of mPFC projections by microscope-objective coupled LEDs (460 nm). B, Response amplitude during paired-pulse stimulation was examined as a proxy for glutamate release probability of mPFC terminals. Scale bars: P15, 150 pA; P30, 80 pA; P45, 500 pA; P60, 150 pA × 100 ms. C, Comparison of paired-pulse ratio (second/first response) revealed a decrease between P21 and P30. Bonferroni post hoc test was conducted on all pairwise comparisons following two-way repeated-measures ANOVA. *[black]p < 0.05, P15 versus P60. *[purple]p < 0.01, P21 versus P30, P45, and P60. **[black]p < 0.01, P15 versus P30, P45, and P60. **[purple]p < 0.01, P21 versus P30, P45, and P60. P15, n = 8 cells (3 mice); P21, n = 11 cells (4 mice); P30, n = 10 cells (5 mice); P45, n = 6 cells (5 mice); P60, n = 22 cells (10 mice). D, Representative EPSCs resulting from optic stimulation at −70 mV and 40 mV during blockade of GABAergic transmission (100 μm picrotoxin). For calculation of AMPA/NMDA ratio, AMPAR-EPSC amplitude was defined as the peak amplitude at −70 mV, a potential at which NMDA receptors contribute negligible current. Conversely, NMDAR-EPSCs were measured at 40 mV at 100 ms after LED stimulation, a time point when AMPA receptor currents have fully decayed and responses are dominated by NMDA currents. E, Developmental increase in AMPA/NMDA ratio. P15, n = 11 cells (3 mice); P21, n = 13 cells (5 mice); P30, n = 12 cells (6 mice); P45, n = 13 cells (5 mice); P60, n = 8 cells (5 mice). Tukey's post hoc test was conducted on all pairwise comparisons following one-way ANOVA. **p < 0.01. F, Developmental increase in maximal amplitude of light-evoked EPSCs at −70 mV. Tukey's post hoc test was conducted on all pairwise comparisons following one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05. G, No change in decay time constant of responses at 40 mV. Inset, Overlay of group-averaged peak-scaled currents at 40 mV, color coded according to scheme in B. P15, n = 10 cells (3 mice); P21, n = 12 cells (4 mice); P30, n = 11 cells (6 mice); P45, n = 13 cells (5 mice); P60, n = 8 cells (5 mice).

In addition to release properties, the strength of excitatory transmission is regulated by the postsynaptic function of AMPA-type glutamate receptors. In particular, the enhancement of AMPA relative to NMDA receptor-mediated currents (AMPA/NMDA ratio) is associated with developmental maturation of primary sensory cortex (Takahashi et al., 2003; Mierau et al., 2004) and mediates experience-dependent strengthening of prelimbic mPFC-BLA synapses (Arruda-Carvalho and Clem, 2014). We therefore quantified AMPA/NMDA ratio as function of developmental age at mPFC synapses. This revealed an increase in AMPA/NMDA ratio between P15 and P30 that, like decreased paired-pulse ratio, persisted at later ages (one-way ANOVA, F(4,52) = 5.694, p = 0.007; Fig. 5D,E). In sensory cortex, it has been reported that the decay time of NMDAR-EPSCs is developmentally regulated (Philpot et al., 2001), which could have confounded our analysis of AMPA/NMDA ratios. However, we did not observe any changes in EPSC decay (Fig. 5G), suggesting that NMDA receptor kinetics are not affected by maturation of this pathway. Furthermore, enhancement of AMPA/NMDA ratio was accompanied by an increase in maximal response amplitude, consistent with synaptic potentiation (one-way ANOVA, F(4,50) = 3.529, p = 0.0130; Fig. 5F). Pharmacological isolation of AMPA receptor-mediated EPSCs at P30 revealed a linear current-voltage relationship (for rectification analysis, see Materials and Methods; rectification index = 1.04 ± 0.14, n = 10 cells, 4 animals), suggesting that increased AMPA/NMDA ratio does not involve the accumulation of calcium-permeable AMPARs.

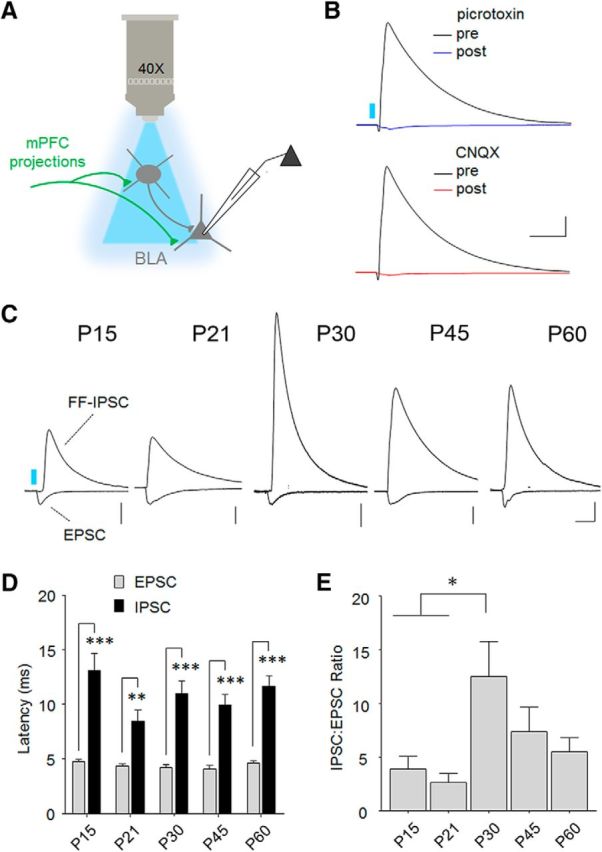

In addition to excitatory responses, we previously demonstrated that stimulation of glutamatergic mPFC terminals recruits disynaptic feedforward IPSCs, which putatively originate from local GABAergic interneurons (Arruda-Carvalho and Clem, 2014). Although BLA contains several distinct GABAergic subtypes, it remains unclear which of these receive mPFC input or mediate feedforward responses. We therefore quantified the potency of feedforward IPSCs relative to monosynaptic excitation triggered under the same stimulus conditions (Fig. 6A). Before performing such an analysis, we first confirmed that IPSCs could be abolished by both GABAA receptor and AMPA/kainate receptor antagonists (Fig. 6B), consistent with a feedforward inhibitory circuit mechanism. In addition, the onset latency of IPSCs was delayed relative to EPSCs (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, main effect of IPSC vs EPSC, F(1,44) = 154.5, p < 0.001; Fig. 6D), and there was no interaction between onset latency and age. Having confirmed that IPSCs originate from feedforward circuits, we then calculated an IPSC/EPSC amplitude ratio, which revealed a sharp but transient increase in relative inhibition at P30 (one-way ANOVA, F(4,45) = 3.33, p = 0.018; Fig. 6C,E). These data indicate that inhibitory/excitatory balance within the mPFC-BLA pathway is not stable across early development but is instead transiently shifted toward inhibition in adolescence.

Figure 6.

Transient potentiation of feedforward inhibition in the mPFC-BLA pathway. A, Diagram of monosynaptic and disynaptic circuit interrogation by optic stimulation (460 nm). To examine the relative potency of feedforward inhibition, IPSCs were first collected at 0 mV before measuring EPSCs at −70 mV in the presence of a GABAA-receptor antagonist (100 μm picrotoxin). B, Confirmation of disynaptic mechanism for IPSCs, which were abolished by both GABAA receptor antagonism (100 μm pictrotoxin) or AMPA/kainate receptor blockade (10 μm CNQX). C, Representative overlays of feedforward IPSCs with monosynaptic EPSCs at each age. Traces were normalized to peak amplitude of EPSCs to illustrate shift in feedforward inhibition. Scale bars: P15, 200 pA; P21, 200 pA; P30, 100 pA; P45, 200 pA; P60, 200 pA × 50 ms. D, Onset latencies of EPSCs and IPSCs at each age were consistent with a monosynaptic and disynaptic mechanism, respectively. Bonferroni post hoc test was conducted on all pairwise comparisons following two-way repeated-measures ANOVA. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. E, IPSC/EPSC amplitude ratio was transiently elevated at P30. Tukey's post hoc test was conducted on all pairwise comparisons following one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05. P15, n = 9 cells (5 mice); P21, n = 8 cells (5 mice); P30, n = 12 cells (6 mice); P45, n = 9 cells (5 mice); P60, n = 12 cells (10 mice).

Discussion

A fundamental process in brain network development is the formation and maturation of long-range circuitry. Nevertheless, for even the most scrutinized pathways, the time course for initiation and completion of these events remains a matter of speculation. Here we describe an optogenetic approach to this question that allowed us to visualize the early proliferation of glutamatergic projections between the mPFC and BLA, and characterize the functional maturation of their transmission within BLA networks. We defined, for the first time, a postnatal window encompassing the appearance of synaptic responses in this pathway followed by their attainment of adult-like properties. These data outline a period of ongoing refinement during which synaptic transmission may be especially sensitive to adverse experiences.

Consistent with preadolescent onset of human mPFC-amygdala connectivity (Gabard-Durnam et al., 2014), our results indicate that mPFC projections first reach appreciable levels in the mouse BLA between P10 and P15, which was delayed relative to projections targeting the claustrum, thalamus, and striatum. Tracer studies in rats suggest that development of mPFC-BLA reciprocal connectivity is itself asynchronous, with BLA projections arriving in mPFC several days before mPFC axons reach BLA (Bouwmeester et al., 2002a, b). Asynchrony of efferent and afferent development might have important consequences for circuit maturation and behavior, for example, by delaying the ontogenesis of behavioral repertoires to coincide with meaningful experience.

The formation of mPFC-BLA synapses was correlated with the largest developmental increase in BLA spontaneous synaptic activity that we observed, and would therefore appear consistent with the notion that mPFC circuits participate in and perhaps influence key events in the early maturation of the BLA. The third postnatal week is a period when mice first explore outside the home nest, where they encounter threats on a regular basis, and correspondingly when their capacity for threat learning emerges (Rudy, 1993; Richardson et al., 2000; Akers et al., 2012; Deal et al., 2016). mPFC-BLA connections may therefore be shaped by this early experience as well as participate in the encoding of early aversive memories, a possibility that remains to be examined. However, aspects of fear regulation involving the mPFC are considered to undergo refinement during adolescence (Pattwell et al., 2013).

Over ∼2 weeks after synapses are established between mPFC and BLA, our data show that they are strengthened through both presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms. By P30, both short-term dynamics and relative AMPA receptor conductance of these connections have reached adult levels. Because there were no changes in sEPSC amplitude or frequency during this timeframe, it is likely that developmental strengthening affects a relatively small proportion of BLA synapses, which would be expected if changes were specific to the mPFC-BLA pathway. The synaptic accumulation of AMPA receptors in sensory areas is thought to be an experience-dependent process that shapes response properties (Feldman, 2009). It is interesting to speculate that such mechanisms may also be at work in mPFC-BLA network development. Strengthening of newly generated synaptic contacts could also contribute to their stabilization (Holtmaat et al., 2006), meaning that early emotional experiences could leave a lasting structural trace in the adult brain.

Recent work draws functional distinctions in threat learning between dorsal and ventral regions of mPFC, and in particular between the prelimbic and infralimbic subdivisions. Accordingly, expression of conditioned threat memories depends on prelimbic, whereas extinction learning requires infralimbic cortex (Giustino and Maren, 2015). Given these roles, an interesting question is whether these subregions exhibit unique developmental trajectories. Within the BLA, however, several new studies indicate similar profiles of axon termination from prelimbic and infralimbic cortex, with the anterior basal nucleus being the principal target of both (Cho et al., 2013; Arruda-Carvalho and Clem, 2014; Hübner et al., 2014; Bukalo et al., 2015; Cheriyan et al., 2016). In addition, we and others have shown that projections from these areas recruit equivalent levels of excitation and feedforward inhibition (Cho et al., 2013; Arruda-Carvalho and Clem, 2014). Maturation of associated synaptic connections is therefore likely to be fundamentally similar, but any differences in the timing of these events could alter the balance between prelimbic and infralimbic transmission. Addressing these possibilities would require selectively targeting these areas in developing animals, a level of precision that would be extremely challenging.

Among the most intriguing changes that we found was a transient increase in the balance of feedforward inhibition to excitation within the mPFC-BLA pathway, which occurred at P30. This shift corresponds to a peak in sIPSC frequency as well as relative inhibition of BLA principal neurons. A likely possibility is that this period is characterized by an excess of synaptic terminals or GABA release from an interneuron population that mediates mPFC feedforward inhibition. Because there are several steps involved in the integration of mPFC input and release of GABA by feedforward interneurons, and potentially more than one inhibitory population involved in this transmission, the precise mechanism for these changes remains to be established. The most direct consequence of potentiated feedforward inhibition would be a shift in the net effect of mPFC glutamate transmission toward inhibitory processes. Interestingly, during a comparable mid-adolescent period in humans, the valence of mPFC-BLA functional connectivity switches from positive to negative (Gee et al., 2013), and the failure to exhibit this transition is associated with increased amygdala reactivity.

The timeframe of these inhibitory changes is also intriguing in light of recent behavioral and anatomical studies. Early adolescence in rodents has been associated with impaired retention of threat memory extinction for auditory cues (Pattwell et al., 2012; Baker et al., 2014). In mice, this impairment is reportedly expressed between P29 and P43 (Pattwell et al., 2012). Interestingly, a similar window (P29-P40) has been associated with temporarily suppressed expression of contextual threat memories (Pattwell et al., 2011). Most interestingly, prelimbic mPFC neurons exhibit higher spine density, and a greater number of mPFC-projecting BLA neurons are observed in P31 compared with P24 and P45 mice (Pattwell et al., 2016). Along with our findings, these changes may provide clues to aberrant threat-related behavior during adolescence, and it is tempting to speculate that their persistence may contribute to psychiatric dysfunction. However, our data could also be more generally indicative of a developmental critical period because the maturation of cortical inhibition is considered to be a key mechanism in critical period timing (Levelt and Hübener, 2012).

In conclusion, we executed a novel approach to interrogating nascent long-range connections in a brain network crucial to emotional and cognitive development. Our results establish a time frame for several important aspects of mPFC-BLA circuit maturation during early life, and suggest potential substrates for normal and abnormal behavioral adaptations. The techniques we describe are highly applicable to other complex circuitry and could provide key insights into brain maturation by delineating specific pathways affected by developmental synaptic plasticity.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant MH105414 to R.L.C., the Brain and Behavior Foundation to R.L.C., and Human Frontiers Science Program Fellowship LT000191/2014-L to M.A.-C. We thank Deanna Benson, Bridget Matikainen, and Roxana Mesias for discussions and technical advice on neonatal surgeries; Stephen Salton for sharing equipment; Ming-Hu Han for donation of viral vectors; and Karl Deisseroth for sharing channelrhodopsin technology.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Akers KG, Arruda-Carvalho M, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW (2012) Ontogeny of contextual fear memory formation, specificity, and persistence in mice. Learn Mem 19:598–604. 10.1101/lm.027581.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anticevic A, Brumbaugh MS, Winkler AM, Lombardo LE, Barrett J, Corlett PR, Kober H, Gruber J, Repovs G, Cole MW, Krystal JH, Pearlson GD, Glahn DC (2013) Global prefrontal and fronto-amygdala dysconnectivity in bipolar I disorder with psychosis history. Biol Psychiatry 73:565–573. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.07.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda-Carvalho M, Clem RL (2014) Pathway-selective adjustment of prefrontal-amygdala transmission during fear encoding. J Neurosci 34:15601–15609. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2664-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda-Carvalho M, Clem RL (2015) Prefrontal-amygdala fear networks come into focus. Front Syst Neurosci 9:145. 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker KD, Den ML, Graham BM, Richardson R (2014) A window of vulnerability: impaired fear extinction in adolescence. Neurobiol Learn Mem 113:90–100. 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ, Choudhury S (2006) Development of the adolescent brain: implications for executive function and social cognition. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47:296–312. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01611.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch D, Ehrlich I (2015) Postnatal maturation of GABAergic modulation of sensory inputs onto lateral amygdala principal neurons. J Physiol 593:4387–4409. 10.1113/JP270645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester H, Smits K, Van Ree JM (2002a) Neonatal development of projections to the basolateral amygdala from prefrontal and thalamic structures in rat. J Comp Neurol 450:241–255. 10.1002/cne.10321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester H, Wolterink G, van Ree JM (2002b) Neonatal development of projections from the basolateral amygdala to prefrontal, striatal, and thalamic structures in the rat. J Comp Neurol 442:239–249. 10.1002/cne.10084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenhouse HC, Andersen SL (2011) Developmental trajectories during adolescence in males and females: a cross-species understanding of underlying brain changes. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35:1687–1703. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukalo O, Pinard CR, Silverstein S, Brehm C, Hartley ND, Whittle N, Colacicco G, Busch E, Patel S, Singewald N, Holmes A (2015) Prefrontal inputs to the amygdala instruct fear extinction memory formation. Sci Adv 1:piie1500251. 10.1126/sciadv.1500251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballedo A, Scheuerecker J, Meisenzahl E, Schoepf V, Bokde A, Möller HJ, Doyle M, Wiesmann M, Frodl T (2011) Functional connectivity of emotional processing in depression. J Affect Disord 134:272–279. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassell MD, Chittick CA, Siegel MA, Wright DJ (1989) Collateralization of the amygdaloid projections of the rat prelimbic and infralimbic cortices. J Comp Neurol 279:235–248. 10.1002/cne.902790207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheriyan J, Kaushik MK, Ferreira AN, Sheets PL (2016) Specific targeting of the basolateral amygdala to projectionally defined pyramidal neurons in prelimbic and infralimbic cortex. eNeuro 3:2. 10.1523/ENEURO.0002-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JH, Deisseroth K, Bolshakov VY (2013) Synaptic encoding of fear extinction in mPFC-amygdala circuits. Neuron 80:1491–1507. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruikshank SJ, Urabe H, Nurmikko AV, Connors BW (2010) Pathway-specific feedforward circuits between thalamus and neocortex revealed by selective optical stimulation of axons. Neuron 65:230–245. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal AL, Erickson KJ, Shiers SI, Burman MA (2016) Limbic system development underlies the emergence of classical fear conditioning during the third and fourth weeks of life in the rat. Behav Neurosci 130:212–230. 10.1037/bne0000130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD (2008) Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci 9:788–796. 10.1038/nrn2345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitriu D, Berger SI, Hamo C, Hara Y, Bailey M, Hamo A, Grossman YS, Janssen WG, Morrison JH (2012) Vamping: stereology-based automated quantification of fluorescent puncta size and density. J Neurosci Methods 209:97–105. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.05.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich DE, Ryan SJ, Hazra R, Guo JD, Rainnie DG (2013) Postnatal maturation of GABAergic transmission in the rat basolateral amygdala. J Neurophysiol 110:926–941. 10.1152/jn.01105.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DE. (2009) Synaptic mechanisms for plasticity in neocortex. Annu Rev Neurosci 32:33–55. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabard-Durnam LJ, Flannery J, Goff B, Gee DG, Humphreys KL, Telzer E, Hare T, Tottenham N (2014) The development of human amygdala functional connectivity at rest from 4 to 23 years: a cross-sectional study. Neuroimage 95:193–207. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.03.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott PL, Warner TA, Jays PR, Salway P, Busby SJ (2005) Prefrontal cortex in the rat: projections to subcortical autonomic, motor, and limbic centers. J Comp Neurol 492:145–177. 10.1002/cne.20738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee DG, Humphreys KL, Flannery J, Goff B, Telzer EH, Shapiro M, Hare TA, Bookheimer SY, Tottenham N (2013) A developmental shift from positive to negative connectivity in human amygdala-prefrontal circuitry. J Neurosci 33:4584–4593. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3446-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giustino TF, Maren S (2015) The role of the medial prefrontal cortex in the conditioning and extinction of fear. Front Behav Neurosci 9:298. 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat A, Wilbrecht L, Knott GW, Welker E, Svoboda K (2006) Experience-dependent and cell-type-specific spine growth in the neocortex. Nature 441:979–983. 10.1038/nature04783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübner C, Bosch D, Gall A, Lüthi A, Ehrlich I (2014) Ex vivo dissection of optogenetically activated mPFC and hippocampal inputs to neurons in the basolateral amygdala: implications for fear and emotional memory. Front Behav Neurosci 8:64. 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Snidman N (1991) Temperamental factors in human development. Am Psychol 46:856–862. 10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62:593–602. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FS, Heimer H, Giedd JN, Lein ES, Šestan N, Weinberger DR, Casey BJ (2014) Mental health: adolescent mental health-opportunity and obligation. Science 346:547–549. 10.1126/science.1260497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levelt CN, Hübener M (2012) Critical-period plasticity in the visual cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci 35:309–330. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levers TE, Edgar JM, Price DJ (2001) The fates of cells generated at the end of neurogenesis in developing mouse cortex. J Neurobiol 48:265–277. 10.1002/neu.1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little JP, Carter AG (2013) Synaptic mechanisms underlying strong reciprocal connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and basolateral amygdala. J Neurosci 33:15333–15342. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2385-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Tang Y, Womer F, Fan G, Lu T, Driesen N, Ren L, Wang Y, He Y, Blumberg HP, Xu K, Wang F (2014) Differentiating patterns of amygdala-frontal functional connectivity in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Bull 40:469–477. 10.1093/schbul/sbt044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonald AJ, Mascagni F, Guo L (1996) Projections of the medial and lateral prefrontal cortices to the amygdala: a Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin study in the rat. Neuroscience 71:55–75. 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00417-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Eiland L, Hunter RG, Miller MM (2012) Stress and anxiety: structural plasticity and epigenetic regulation as a consequence of stress. Neuropharmacology 62:3–12. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierau SB, Meredith RM, Upton AL, Paulsen O (2004) Dissociation of experience-dependent and -independent changes in excitatory synaptic transmission during development of barrel cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:15518–15523. 10.1073/pnas.0402916101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J. (1981) The ontogeny of play in rats. Dev Psychobiol 14:327–332. 10.1002/dev.420140405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passarotti AM, Ellis J, Wegbreit E, Stevens MC, Pavuluri MN (2012) Reduced functional connectivity of prefrontal regions and amygdala within affect and working memory networks in pediatric bipolar disorder. Brain Connect 2:320–334. 10.1089/brain.2012.0089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattwell SS, Bath KG, Casey BJ, Ninan I, Lee FS (2011) Selective early-acquired fear memories undergo temporary suppression during adolescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:1182–1187. 10.1073/pnas.1012975108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattwell SS, Duhoux S, Hartley CA, Johnson DC, Jing D, Elliott MD, Ruberry EJ, Powers A, Mehta N, Yang RR, Soliman F, Glatt CE, Casey BJ, Ninan I, Lee FS (2012) Altered fear learning across development in both mouse and human. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:16318–16323. 10.1073/pnas.1206834109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattwell SS, Lee FS, Casey BJ (2013) Fear learning and memory across adolescent development: Hormones and Behavior Special Issue: Puberty and Adolescence. Horm Behav 64:380–389. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattwell SS, Liston C, Jing D, Ninan I, Yang RR, Witztum J, Murdock MH, Dincheva I, Bath KG, Casey BJ, Deisseroth K, Lee FS (2016) Dynamic changes in neural circuitry during adolescence are associated with persistent attenuation of fear memories. Nat Commun 7:11475. 10.1038/ncomms11475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN (2008) Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci 9:947–957. 10.1038/nrn2513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin K (2001) The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pellis SM, Pasztor TJ (1999) The developmental onset of a rudimentary form of play fighting in C57 mice. Dev Psychobiol 34:175–182. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2302(199904)34:3%3C175::AID-DEV2%3E3.3.CO;2-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellis SM, Pellis VC, Whishaw IQ (1992) The role of the cortex in play fighting by rats: developmental and evolutionary implications. Brain Behav Evol 39:270–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman SB, Almeida JR, Kronhaus DM, Versace A, Labarbara EJ, Klein CR, Phillips ML (2012) Amygdala activity and prefrontal cortex-amygdala effective connectivity to emerging emotional faces distinguish remitted and depressed mood states in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 14:162–174. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.00999.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpot BD, Sekhar AK, Shouval HZ, Bear MF (2001) Visual experience and deprivation bidirectionally modify the composition and function of NMDA receptors in visual cortex. Neuron 29:157–169. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00187-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson R, Paxinos G, Lee J (2000) The ontogeny of conditioned odor potentiation of startle. Behav Neurosci 114:1167–1173. 10.1037/0735-7044.114.6.1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy JW. (1993) Contextual conditioning and auditory cue conditioning dissociate during development. Behav Neurosci 107:887–891. 10.1037/0735-7044.107.5.887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Deutch AY, Roth RH, Bunney BS (1989) Topographical organization of the efferent projections of the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat: an anterograde tract-tracing study with Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin. J Comp Neurol 290:213–242. 10.1002/cne.902900205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Svoboda K, Malinow R (2003) Experience strengthening transmission by driving AMPA receptors into synapses. Science 299:1585–1588. 10.1126/science.1079886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Niesink RJ, Van Ree JM (1997) The neurobiology of social play behavior in rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 21:309–326. 10.1016/S0149-7634(96)00020-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP. (2002) Analysis of projections from the medial prefrontal cortex to the thalamus in the rat, with emphasis on nucleus reuniens. J Comp Neurol 442:163–187. 10.1002/cne.10083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Südhof TC (2013) A neural circuit for memory specificity and generalization. Science 339:1290–1295. 10.1126/science.1229534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Miller MI, Plachez C, Richards LJ, Yarowsky P, van Zijl P, Mori S (2005) Mapping postnatal mouse brain development with diffusion tensor microimaging. Neuroimage 26:1042–1051. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]