Abstract

Most ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide (RiPP) natural products are processed by tailoring enzymes to create complex natural products that are still recognizably peptide-based. However, some tailoring enzymes dismantle the peptide en route to synthesis of small molecules. A small molecule natural product of as yet unknown structure, mycofactocin, is thought to be synthesized in this way via the mft gene cluster found in many strains of mycobacteria. This cluster harbors at least six genes, which appear to be conserved across species. We have previously shown that one enzyme from this cluster, MftC, catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of the C-terminal Tyr of the substrate peptide MftA in a reaction that requires the MftB protein. Herein we show that mftE encodes a creatininase homolog that catalyzes cleavage of the oxidatively decarboxylated MftA peptide to liberate its final two residues, including the C-terminal decarboxylated Tyr (VY*). Unlike MftC, which requires MftB for function, MftE catalyzes the cleavage reaction in the absence of MftB. The identification of this novel metabolite, VY*, supports the notion that the mft cluster is involved in generating a small molecule from the MftA peptide. The ability to produce VY* from MftA by in vitro reconstitution of the activities of MftB, MftC, and MftE sets the stage for identification of the novel metabolite that results from the proteins encoded by the mft cluster.

Keywords: enzyme catalysis, enzyme mechanism, natural product biosynthesis, proteolytic enzyme, secondary metabolism

Introduction

Peptide-derived natural products are implicated in myriad biological functions and hold great potential as novel therapeutic agents. Despite the enormous sequence diversity and wide range of modifications that are encountered, these metabolites are either synthesized by non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (1, 2) and matured by tailoring enzymes or ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs)3 (3). RiPPs have emerged as an important class of peptide-derived natural products. The gene encoding the RiPP precursor peptide is often co-localized with genes that encode the maturase enzymes, making discovery of novel RiPP biosynthetic clusters by bioinformatics possible. Given the diverse structures of mature RiPPs, a wide variety of novel RiPP tailoring reactions are suspected to exist in nature, although the mechanisms underlying many of these reactions remain unknown.

A subset of RiPPs undergo maturation by radical-mediated routes leading to formation of thioether (4–10), Lys-Trp (11) or Glu-Tyr (12) peptide cross-links, oxidative decarboxylation (13, 14), or epimerization (15, 16). These unusual transformations are catalyzed by enzymes of the radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) superfamily (17) that leverage the reductive cleavage of SAM, generating a strong oxidant, 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical (5′-dAdo•), to initiate radical-mediated transformations (18).

In 2011, Haft (19) proposed the presence of a novel peptide-derived metabolite in the Mycobacterium genus based solely on the clustering of the mftA gene that encodes for a short peptide with the mftB and mftC genes that encode a short protein and a member of the radical SAM superfamily, respectively (Fig. 1A). It was noted that this clustering of genes in the Mycobacterium genus is analogous to the clustering of the pqqA, pqqD, and pqqE genes, which are required for the biosynthesis of pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) cofactor as well as bacteriocin biosynthetic gene clusters (19). PQQ is a small molecular weight redox mediator derived from the 23-amino acid peptide encoded by the pqqA gene (20–22). By analogy, it was proposed that the newly described cluster produces a hypothetical metabolite, mycofactocin, which may be a putative small molecule redox cofactor derived from the peptide MftA (19).

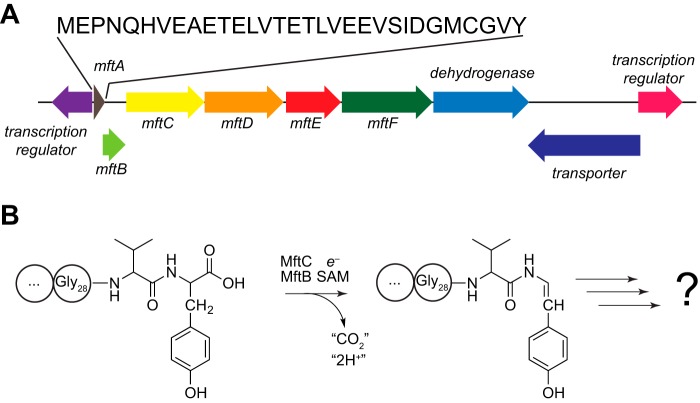

FIGURE 1.

The gene encoding MftE is clustered with those encoding MftA, MftB, and MftC in mycobacteria. A, cluster of genes near the mftA gene in M. smegmatis ATCC 700084. The mftA, mftB, and mftC encode the peptide substrate, accessory protein, and a member of the radical SAM superfamily, respectively. B, MftC catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of the MftA peptide in an MftB-dependent manner in the presence of SAM and a strong reductant, such as dithionite. MftE is shown to encode a peptidase in this study. The functions of the other conserved ORFs and the identity of the product derived from the mftA gene are not known.

We recently reported that the radical SAM enzyme MftC catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of the C-terminal Tyr residue of the MftA peptide in a reaction that also requires the MftB accessory protein (Fig. 1B) (13). Subsequently, Latham and co-workers (14) demonstrated that MftB binds MftA with a submicromolar KD (∼100 nm) and MftC with a low micromolar KD (2 μm). Although the activity of MftC is not analogous to that of the radical SAM enzyme PqqE in PQQ biosynthesis (12), it is still possible that the formation of the oxidatively decarboxylated MftA peptide represents the first step in a biosynthetic pathway to a novel metabolite.

In addition to the mftB and mftC genes, the mftA gene is nearly universally observed clustered with genes that encode proteins that display amino acid sequence similarity to a heme/flavin dehydrogenase (mftD), creatininase (mftE), and glycosyltransferase (mftF) (Fig. 1A). We hypothesized that if MftC does indeed catalyze the first transformation in the biosynthesis of a novel MftA-derived metabolite then one of these gene products may modify the oxidatively decarboxylated MftA product. One would predict that if the putative metabolite derived from MftA is a small molecule redox cofactor analogous to PQQ then there must be a step subsequent to MftC that further processes the modified MftA.

Many RiPP biosynthetic pathways encode peptidases that engage in processing the propeptide into the mature product. Although a peptidase is not encoded by the Mft cluster, we were intrigued by the presence of a gene that encodes a protein with similarity to the creatininase subfamily of amidohydrolases. The prototypical creatininase hydrolyzes an amide bond in the cyclic metabolite creatinine to produce creatine (23–25). We reasoned that it might be possible that the creatininase homolog encoded in this cluster potentially processes the decarboxylated MftA to a smaller metabolite en route to the mature natural product.

Herein we report the biochemical characterization of the creatininase homolog encoded by the gene LI98_07105, hereafter referred to as mftE, clustered with the mftA gene in the genome of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Indeed, MftE catalyzes the hydrolysis of the amide bond between Gly28 and Val29 of MftA peptide only after it has undergone the C-terminal oxidative decarboxylation. Chemical derivatization of the product of MftE is consistent with the valine containing a primary amine. Moreover, we observed that the oxidatively decarboxylated tyrosine displays an unexpected reactivity toward chemical modifiers, which may foreshadow the function of the mature metabolite.

Results

Expression and Purification of MftE

To determine the function of MftE, the homolog from M. smegmatis ATCC 7000840 (LI98_07105) was cloned, the His6-tagged recombinant protein was expressed in Escherichia coli, and the recombinant protein was purified to ≥95% purity (as judged by SDS-PAGE) by nickel affinity chromatography. Amino acid analysis of the protein was carried out to obtain a correction factor of 1.9 ± 0.3 for the Bradford assays with BSA as standard. ICP-MS analysis of the protein revealed the presence of 0.39 ± 0.06 mol of zinc, 0.21 ± 0.03 mol of iron, and 0.042 ± 0.002 mol of manganese per mol of MftE.

MftE Modifies the Decarboxylated MftA

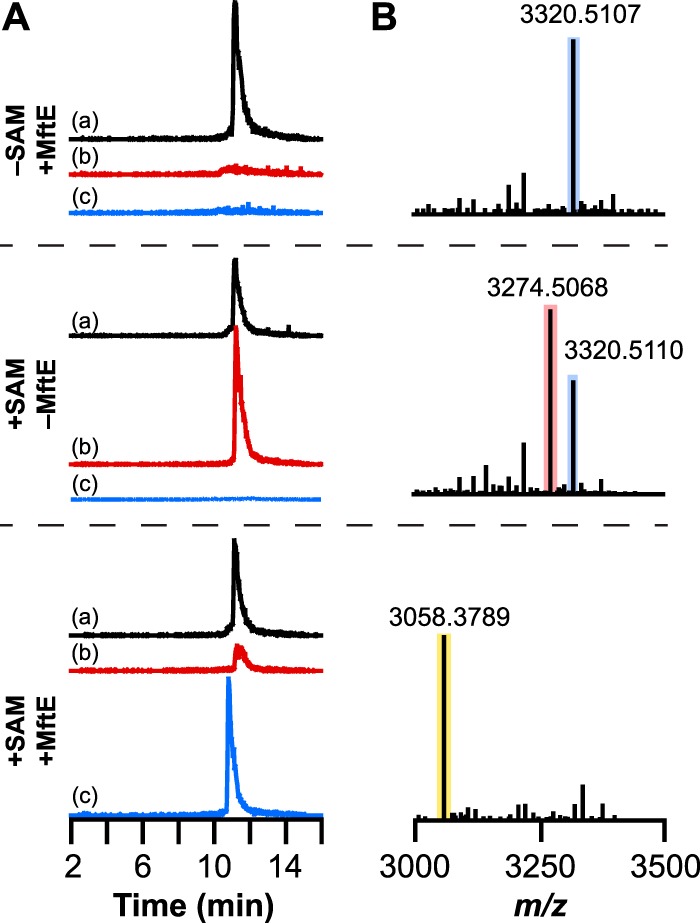

The purified enzyme was incubated with MftA in the presence of MftB and MftC under various conditions and analyzed for MftA modification by UHPLC-MS (Fig. 2). Although unmodified and decarboxylated MftA co-elute at approximately 11 min, the two are readily distinguished by mass spectrometry monitoring at m/z 1661 and 1638, which correspond to the +2 charge state mass envelopes of the unmodified and decarboxylated peptide, respectively (Fig. 2A). When MftA is incubated with MftB, MftC, and reductant in the absence of SAM, the peptide remains unmodified in the presence of MftE. The deconvoluted mass spectrum (supplemental Fig. S1) exhibits a peak at m/z 3320.5107 corresponding to [M + H]+ (theoretical m/z = 3320.5185 for [M + H]+, 2.3 ppm error), which is consistent with the mass of unmodified MftA (Fig. 2B). In the presence of SAM, the +2 charge state species with m/z of 1661 is converted to one with m/z of 1638, which is consistent with the oxidative decarboxylation of MftA catalyzed by MftC/MftB reported previously (13). The deconvoluted mass spectrum shows a peak at m/z 3274.5068 ([M + H]+), which is within 1.9 ppm of the expected value (theoretical m/z = 3274.5130). However, when MftE and SAM are incubated along with MftA, MftB, and MftC, a new species is observed with a +2 charge state peak at m/z 1529. The deconvoluted mass spectrum reveals an m/z of 3058.3789 for [M + H]+, consistent with further modification of the peptide only after the oxidative decarboxylation catalyzed by MftC.

FIGURE 2.

UHPLC-MS analysis of MftA modification by MftE. A, extracted ion chromatograms corresponding to the +2 charge state of MftA peptide are shown. In control reactions, either SAM (−SAM +MftE) or MftE (+SAM −MftE) was omitted. In each extracted ion chromatogram, a corresponds to unmodified MftA (m/z = 1660.5–1661.5), b corresponds to the oxidatively decarboxylated MftA (m/z = 1637.5–1638.5) resulting from the reaction of MftA with MftC in the presence of SAM and MftB, and c corresponds to a truncated MftA peptide that comprises Glu1–Gly28 (MftA(1–28)) (m/z = 1529.5–1530.5). B, the deconvoluted [M + H]+ mass spectra were generated from the full mass spectra in supplemental Fig. S1. These show the loss of 46.0042 atomic mass units upon action of MftB + MftC and 216.1279 atomic mass units after further modification of the oxidatively decarboxylated MftA by MftE. The blue, red, and yellow boxes correspond to unmodified MftA, oxidatively decarboxylated MftA, and MftA(1–28), respectively.

The reactions carried out in the presence of MftA, MftB, MftC, and MftE suggest that the decarboxylated MftA undergoes an additional modification, likely a cleavage, to presumably produce two products. The mass of the newly formed MftA-based product is 216.1279 atomic mass units less than oxidatively decarboxylated MftA (m/z = 3724.5068 for [M + H]+). This difference is consistent with MftE catalyzing the hydrolysis of the amide bond between Gly28 and Val29 to liberate a shortened MftA peptide containing residues Glu1–Gly28 (MftA(1–28)). The theoretical m/z for [M + H]+ of an MftA peptide containing residues 1–28 (MftA(1–28)) is 3058.3867, which is within 2.6 ppm error of that observed in the deconvoluted mass spectrum of the peptide experimentally (see Fig. 2B).

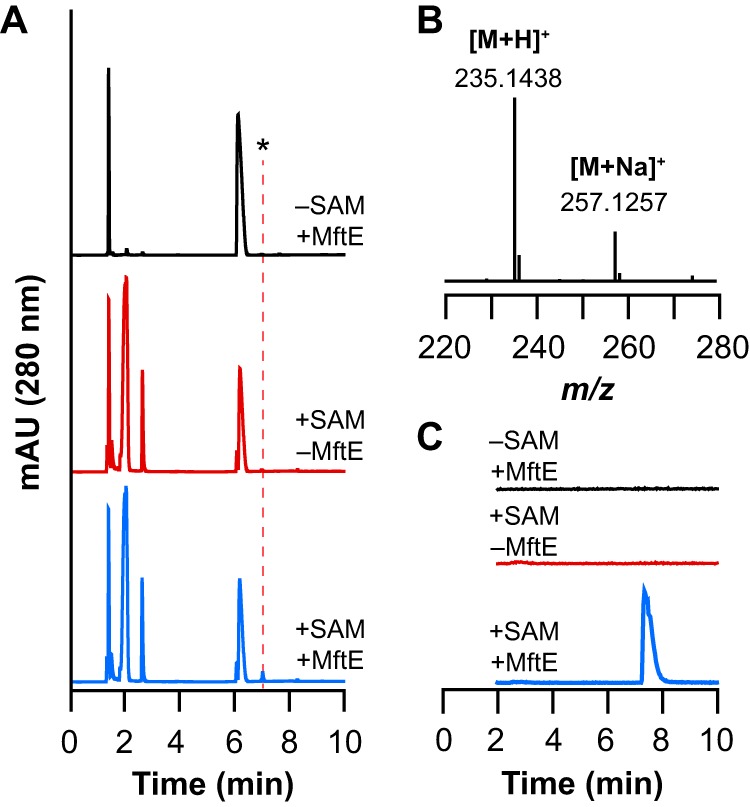

To determine whether MftE is indeed catalyzing the hydrolysis of the amide bond, the chromatograms were analyzed for a peak corresponding to the putative valine-oxidatively decarboxylated tyrosine (VY*) product. In the UV traces of chromatograms corresponding to the reactions shown in Fig. 2, a new peak that elutes at approximately 7.3 min is observed that is only present when all of the reaction components are present (Fig. 3A). This species has an m/z of 235.1438, which is within 3.8 ppm of the theoretical mass (m/z = 235.1447 for [M + H]+) of the VY* resulting from the hydrolysis of the oxidatively decarboxylated MftA peptide (Fig. 3B). The VY* is not present in the UV or extracted ion chromatogram of the reactions where either SAM or MftE is omitted (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these results are consistent with MftE catalyzing the hydrolysis of the amide bond between Gly28 and Val29 to generate the VY* dipeptide.

FIGURE 3.

UHPLC-MS analysis of reactions monitoring for new product that corresponds to valine and oxidative decarboxylated tyrosine (VY*) dipeptide from reaction containing natural abundance MftA. A, UHPLC chromatogram monitoring at 280 nm for reactions containing both SAM and MftE (+SAM +MftE) or controls where either SAM (−SAM +MftE) or MftE (+SAM −MftE) were omitted. The new peak indicated by the asterisk (*) that elutes at approximately 7.3 min is only observed in the +SAM +MftE reaction. B, mass spectrum averaged across the peak at approximately 7.8 min. The observed m/z of 235.1438 corresponds to the [M + H]+ of the VY* (theoretical m/z = 235.1447, 3.8 ppm error). The observed m/z of 257.1257 corresponds to the [M + Na]+ of the VY*. C, the extracted ion chromatogram monitoring m/z 234.5–235.5 corresponding to the theoretical m/z of the VY*. The new peak in the extracted ion chromatogram (at 7.8 min) is observed only in the presence of SAM and MftE. This species is not present in reactions where either SAM (−SAM +MftE) or MftE (+SAM −MftE) is omitted. mAU, milliabsorbance units.

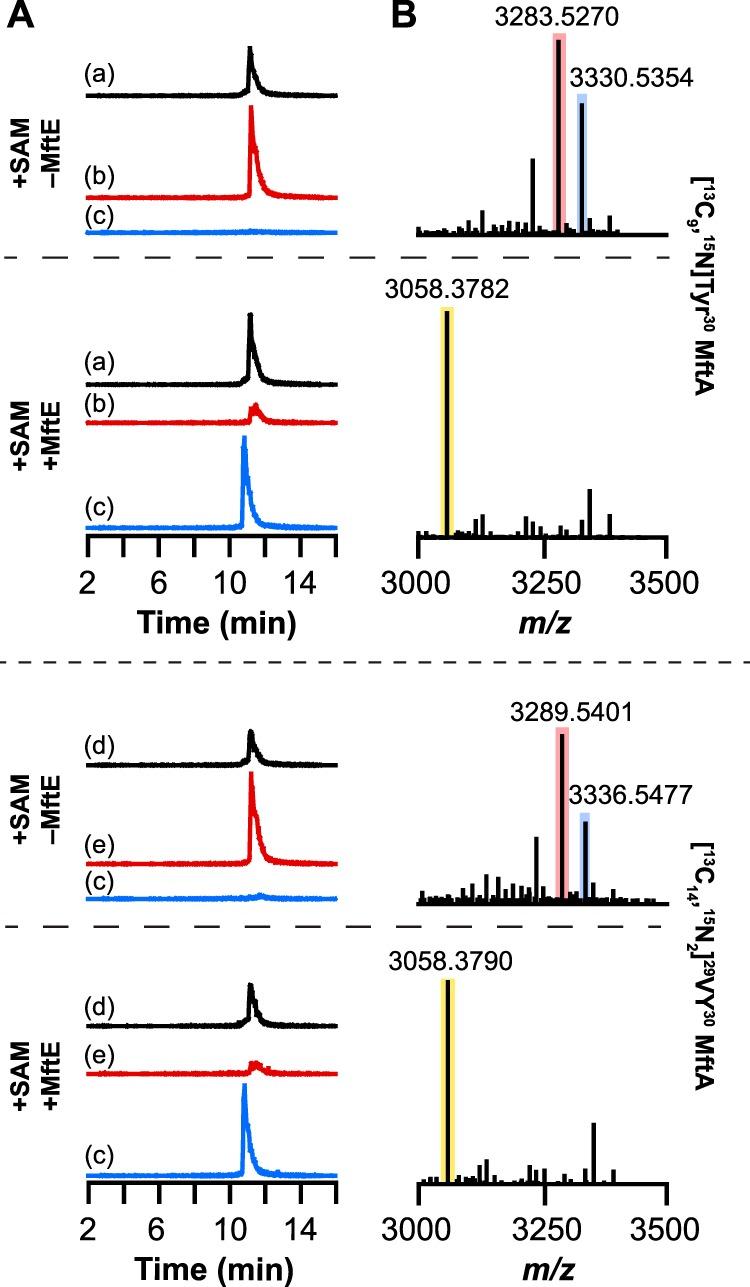

To confirm the identity of the MftE catalyzed reaction, we probed the reaction with two MftA peptides that were isotopically enriched at the C-terminal Tyr only ([13C9,15N]Tyr30 MftA) (see Ref. 13 for synthesis and characterization) or at both Val29 and Tyr30 ([13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA) (see supplemental Fig. S2). If MftE catalyzes the hydrolysis of the peptide bond between Gly28 and Val29 the MftA(1–28) product of the reaction would be expected to be identical in mass to that of unlabeled MftA regardless of which peptide is used, whereas VY* would exhibit an increase in mass consistent with the isotopic enrichment of the amino acids. Indeed, incubation of each isotopically enriched MftA peptide with MftE, MftB, and MftC under reducing conditions in the presence of SAM reveals the same species (within 2.5–2.8 ppm error) as that with unlabeled MftA, corresponding to MftA(1–28), regardless of whether [13C9,15N]Tyr30 MftA or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA was included in the assays (Fig. 4; for full mass spectra, see supplemental Fig. S3). The deconvoluted mass spectra show the expected isotopic enrichment in the [M + H]+ peaks corresponding to the unmodified (m/z = 3330.5354 and m/z = 3336.5477; theoretical, 3330.5457 and 3336.5595, respectively) and the oxidatively decarboxylated (m/z = 3283.5270 and m/z = 3289.5401; theoretical, 3283.5369 and 3289.5507, respectively) MftA peptides isolated from the control reaction lacking MftE that contained either [13C9,15N]Tyr30 or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA, respectively (Fig. 4B). Each of these observed masses are within 3.5 ppm error of the respective theoretical m/z corresponding to the [M + H]+ for the isotopically enriched unmodified or oxidatively decarboxylated MftA peptide. Collectively, the species observed in the deconvoluted mass spectrum of the reaction is consistent with a shortened MftA (with an m/z of 3058.3789 for [M + H]+) that no longer contains Val29 or the oxidatively decarboxylated Tyr30.

FIGURE 4.

UHPLC-MS analysis of MftA peptide isolated from reactions containing either [13C9,15N]Tyr30 MftA or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA. A, the extracted ion chromatograms of reactions in the presence or absence of MftE. The chromatograms correspond to the +2 charge state of unmodified [13C9,15N]Tyr30 MftA (m/z = 1665.5–1666.5) (a), oxidatively decarboxylated [13C9,15N]Tyr30 MftA (m/z = 1642–1643) (b), MftA(1–28) (m/z = 1529.5–1530.5) (c), unmodified [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA (m/z = 1668.5–1669.5) (d), and oxidatively decarboxylated [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA (m/z = 1645–1646) (e). B, the deconvoluted mass spectra generated from the corresponding full mass spectra shown in supplemental Fig. S3. Regardless of which isotopically enriched MftA peptide was used, the new species observed in the extracted ion chromatograms of reactions containing both SAM and MftE has the same mass as the new product observed with natural abundance MftA corresponding to MftA(1–28) shown in Fig. 2B. The blue, red, and yellow boxes correspond to unmodified MftA, oxidatively decarboxylated MftA, and MftA(1–28), respectively.

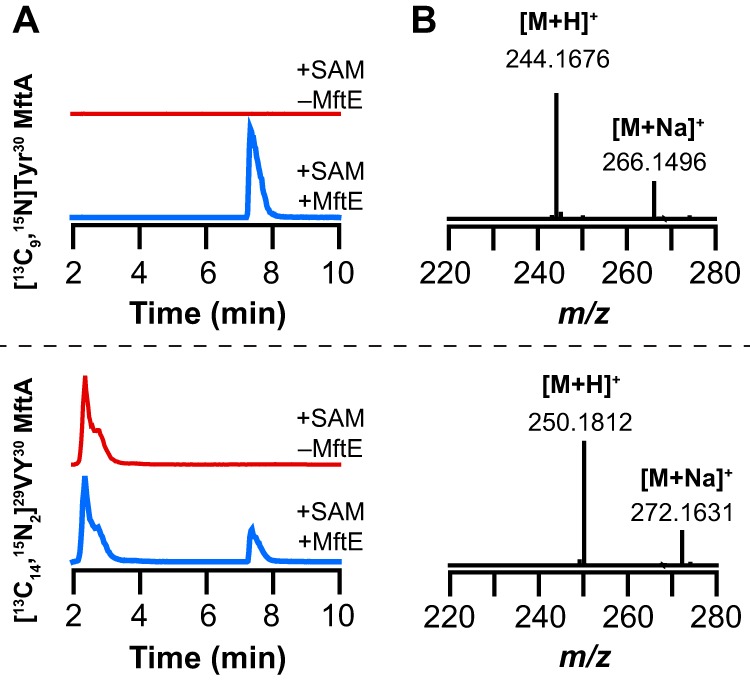

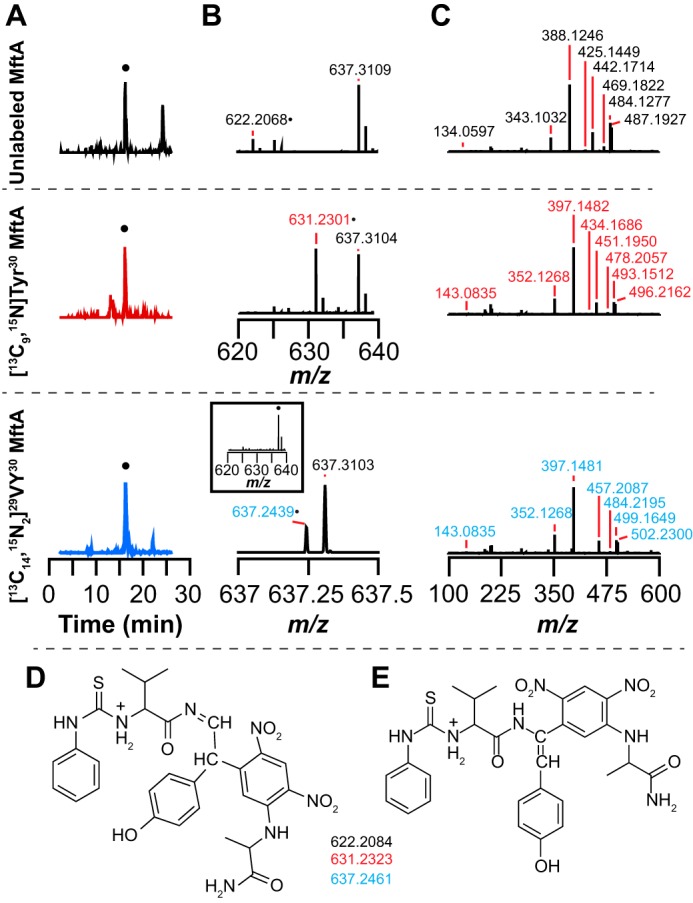

We next examined the identity of the second product formed by MftE using either the [13C9,15N]Tyr30 or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA peptide with all of the reaction components (Fig. 5A). The UHPLC-MS data show that when MftA is uniformly labeled with 13C and 15N at position 30 the peak for the putative VY* product shifts 9.0238 atomic mass units to m/z 244.1676, which is consistent with the isotopically enriched product containing eight 13C and one 15N atoms from the oxidatively decarboxylated MftA peptide (theoretical m/z = 244.1685 for [M + H]+, 3.7 ppm error) (Fig. 5B). By contrast, when MftA with uniform 13C and 15N labels at the C-terminal Val and Tyr are used, the product is 15.0374 atomic mass units greater in mass relative to the product isolated from the reaction containing natural abundance MftA (Fig. 3B). The observed m/z of 250.1812 is within 4.4 ppm error of the theoretical m/z of 250.1823 corresponding to the [M + H]+ VY* containing 13 13C and two 15N atoms (Fig. 5B). These data establish that MftE catalyzes the cleavage of oxidatively decarboxylated MftA to generate MftA(1–28) and VY*.

FIGURE 5.

UHPLC-MS analysis of reactions monitoring for new product that corresponds to valine and oxidative decarboxylated tyrosine (VY*) dipeptide isolated from reactions containing either [13C9,15N]Tyr30 MftA or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA. A, the extracted ion chromatograms monitoring for the VY* dipeptide isolated from reactions where MftE was omitted (+SAM −MftE) or present (+SAM +MftE) when incubated with [13C9,15N]Tyr30 MftA (monitoring at m/z = 243.5–244.5) or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA (monitoring at m/z = 249.5–250.5). B, the full mass spectra averaged over the peak in the extracted ion chromatogram that elutes at approximately 7.8 min in A. The observed [M + H]+ of 244.1676 is consistent with the VY* dipeptide containing eight 13C and one 15N atoms (theoretical m/z = 244.1685, 3.7 ppm error). The observed [M + H]+ of 250.1812 is consistent with the VY* dipeptide containing 13 13C and two 15N atoms (theoretical m/z = 250.1823, 4.4 ppm error).

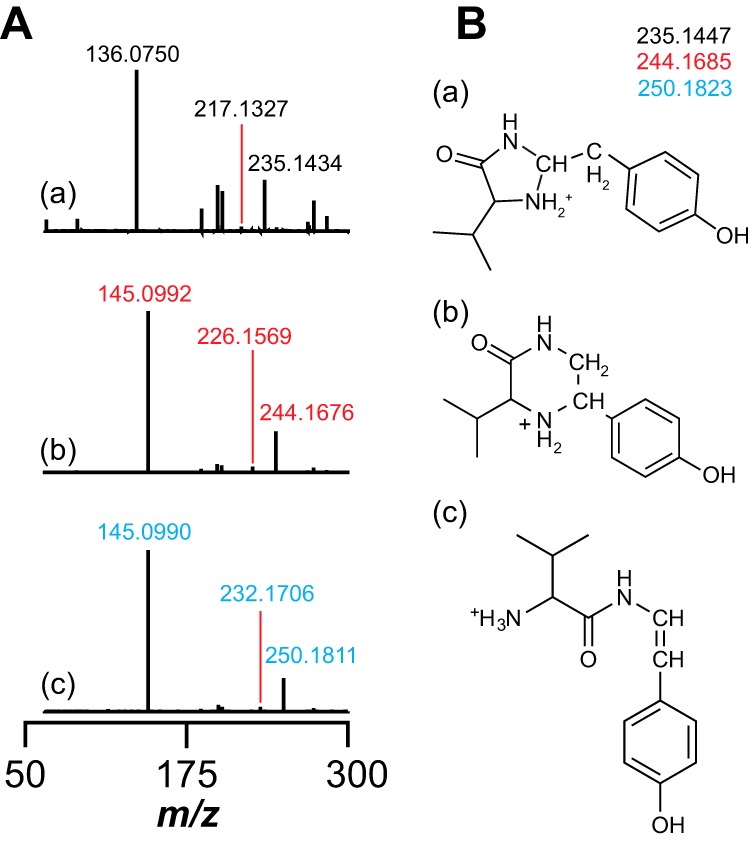

HCD MS/MS Fragmentation of VY*

To further probe the structure of the VY*, we subjected the unlabeled and isotopically enriched VY* dipeptide to HCD fragmentation (35% collision energy) in the mass spectrometer (Fig. 6A). Only two peaks were observed in the resulting MS/MS fragmentation spectrum. The species with m/z values of 217.1327 and 136.0750 in the spectrum obtained with unlabeled VY* are consistent with the loss of water (theoretical m/z = 217.1341, 6.5 ppm error) and decarboxylated tyrosine (theoretical m/z = 136.0762, 8.8 ppm error) (Fig. 6A, a). The MS/MS fragmentation spectrum of each of the isotopically enriched VY* dipeptides (obtained using [13C9,15N]Tyr30 or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA) revealed that the species with an m/z of 136.0750 increases by 9.0242 atomic mass units when either isotopically enriched peptide is used, but the species consistent with the loss of water increases by 9.0242 and 15.0379 atomic mass units for the VY* obtained with [13C9,15N]Tyr30 and [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA, respectively (Fig. 6A, b and c). These fragmentation results establish the identity of VY*.

FIGURE 6.

A, MS/MS analysis of VY*. HCD MS/MS spectra of the VY* dipeptide isolated from reactions containing either unlabeled MftA (a), [13C9,15N]Tyr30 MftA (b), or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA (c) are shown. The m/z of 136.0750 (a) and m/z of 145.0992 (b and c) correspond to natural abundance and 13C8,15N-enriched oxidatively decarboxylated tyrosine, respectively. The peaks with m/z of 217.1327 (a), m/z of 226.1569 (b), and m/z of 232.1706 (c) correspond to VY* dipeptide minus water with either no, 13C8,15N, or 13C13,15N2 isotopic enrichment. B, three possible structures of the VY* dipeptide consistent with the full mass spectra and HCD mass spectra data with the theoretical m/z corresponding to the natural abundance, 13C8,15N-, or 13C13,15N2-enriched product.

Chemical Modification of the VY*

The data presented thus far are consistent with MftE catalyzing the hydrolysis of the amide bond between Gly28 and Val29 to generate the VY* product. One can draw at least three distinct structures of the VY* dipeptide product, each of which has a theoretical m/z of 235.1447 corresponding to [M + H]+ (Fig. 6B). Although the ability to fragment to Val and Tyr* strongly support the notion that it retains a free N terminus at Val, we carried out modification studies to unambiguously establish this and rule out forms where the amino group on valine cyclizes with Tyr*.

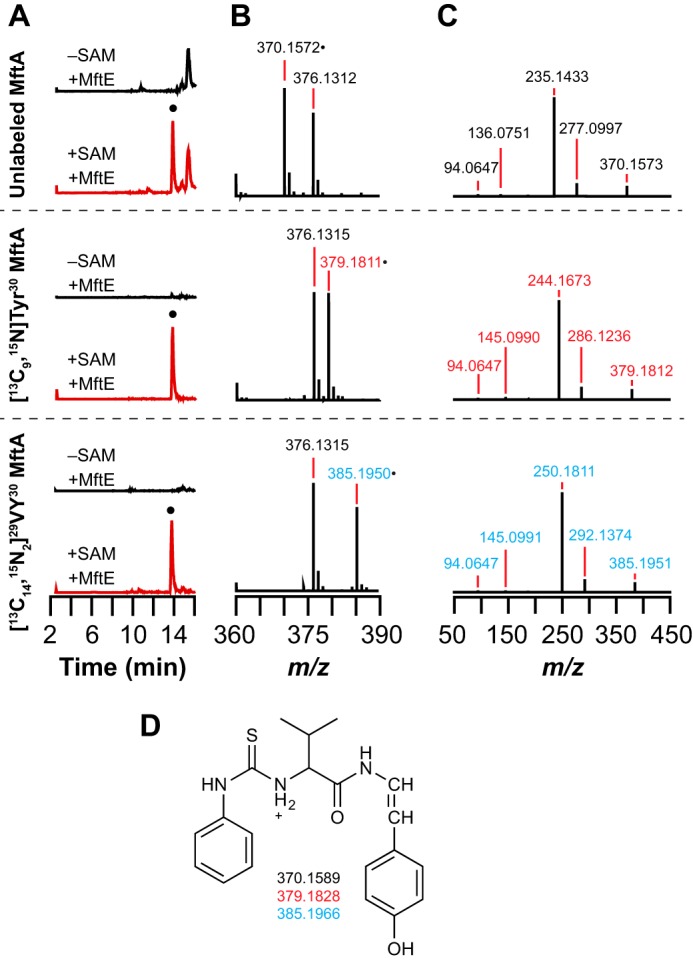

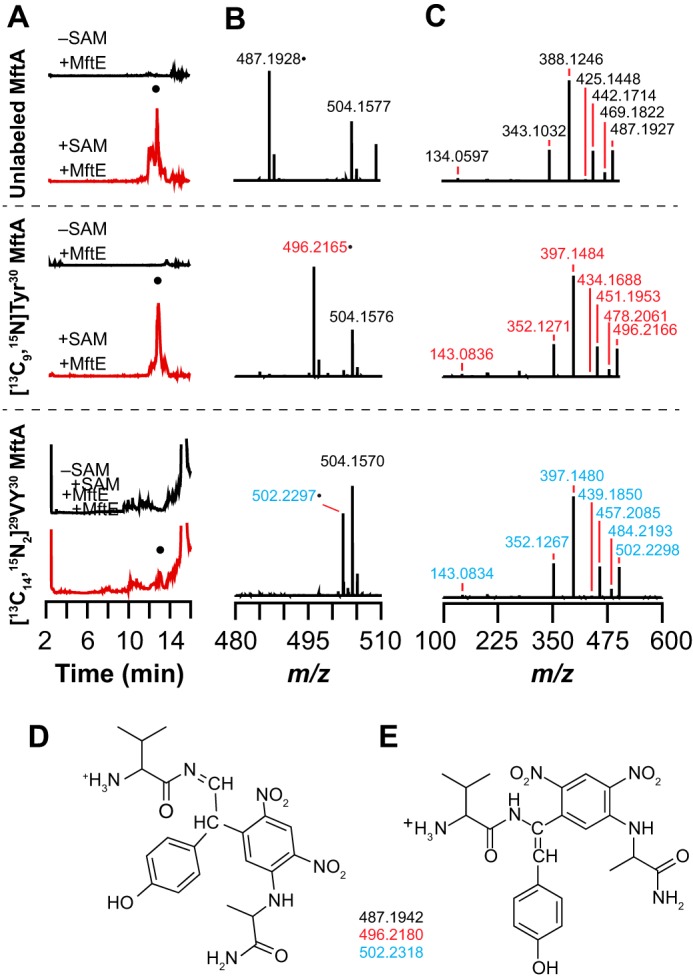

PITC and 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-l-alanine amide (Marfey's reagent) are commonly used to chemically modify primary amines on amino acids. In the presence of PITC, a new SAM-dependent peak is observed at 14 min in the extracted ion chromatogram monitoring the m/z for the [M + H]+ of PITC-VY* obtained from reactions that contained MftE and either natural abundance, [13C9,15N]Tyr30, or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA (Fig. 7A, peak indicated by ●). With the unlabeled substrate, the [M + H]+ ion with an m/z of 370.1572 (Fig. 7B) is within 4.6 ppm error of the theoretical value (m/z = 370.1589). The corresponding species with [13C9,15N]Tyr30 or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA are 9.0239 and 15.0378 atomic mass units heavier than the PITC-modified natural abundance product, respectively (Fig. 7B). The fragmentation of the molecular ions by HCD leads to five related fragments (Fig. 7C), which are consistent with the structures shown in supplemental Fig. S4. Taken together, the fragmentation data allow us to assign the peak at m/z 370.1572 and the corresponding peaks with labeled peptides to PITC-VY* (Fig. 7D).

FIGURE 7.

PITC derivatization of the VY* dipeptide isolated from reactions containing unlabeled MftA, [13C9,15N]Tyr30 MftA, or[13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA. A, a new peak is observed in the extracted ion chromatograms that elutes at approximately 14 min when monitoring for the PITC-derivatized VY* dipeptide with either no (m/z = 369.8–370.8), 13C8,15N (m/z = 378.8–379.8), or 13C13,15N2 (m/z = 384.8–385.8) isotopic enrichment. The species denoted by ● that elutes at approximately 14 min is only observed in reactions containing MftE and SAM (+SAM +MftE) and is not observed in reactions lacking SAM (−SAM +MftE). B, full mass spectra of the species that elutes at approximately 14 min in the extracted ion chromatograms showing isotope-sensitive peaks for the [M + H]+ at m/z 376.1312, 379.1811, and 385.1950 with unlabeled MftA, [13C9,15N]Tyr30 MftA, or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA. The species with an m/z of 376 is present in all of the samples and is a background peak. C, the isotope-sensitive [M + H]+ peaks in B were isolated and subjected to HCD fragmentation. Possible structures for the fragments are shown in supplemental Fig. S4. D, the proposed structure and corresponding theoretical masses of the PITC-derivatized VY* dipeptide based on the HCD fragmentation results with the natural abundance and isotopically enriched MftA peptides.

We next examined the modification of VY* by Marfey's reagent and the corresponding fragmentation products when unlabeled or isotopically enriched peptides were used. Fig. 8A shows the extracted ion chromatograms corresponding to the theoretical m/z of the [M + H]+ for Marfey's reagent-labeled VY* generated in reactions that contained SAM and MftE or controls where SAM was omitted. The mass spectrum averaged across the peak indicated by ● in the extracted ion chromatograms shows that the observed mass in each spectrum is consistent with the absence or presence of the appropriate 13C and 15N isotopes, and each is within 3.2 ppm error relative to the theoretical mass for [M + H]+ (Fig. 8B). The HCD fragmentation of the molecular ion peak reveals seven related fragments (Fig. 8C). Surprisingly, the fragments in the unlabeled and the isotopically enriched Marfey's reagent-modified VY* are most consistent with the Marfey's reagent modifying the oxidatively decarboxylated tyrosine. The two fragments that are consistent with Marfey's reagent covalently attached to the tyrosine are m/z 343.1032 and m/z 388.1246 in the unlabeled VY* reactions and m/z 352.1721 (352.1267) and m/z 397.1484 (397.1480) in both spectra with the isotopically enriched VY*. These fragments contain only oxidatively decarboxylated tyrosine and Marfey's reagent. This is further demonstrated by the fact that in the HCD spectrum of the VY* product isolated from the reaction containing [13C9,15N]Tyr30 MftA a 9.0237-atomic mass unit mass shift is observed in the adduct. An identical mass increase is also observed in the VY* isolated from the reaction containing [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA, indicating that no valine remains in this fragment. Therefore, these HCD fragmentation spectra are most consistent with the Marfey's reagent reacting with the oxidatively decarboxylated Tyr of the VY* dipeptide.

FIGURE 8.

Marfey's reagent derivatization of the VY* dipeptide isolated from reactions containing natural abundance MftA, [13C9,15N]Tyr30 MftA, or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA. A, a new species (●) is observed in the extracted ion chromatograms that elutes at approximately 13 min when monitoring for the Marfey's reagent-derivatized VY* dipeptide with either no (unlabeled) (m/z = 486.8–487.7), 13C8,15N (m/z = 495.8–496.8), or 13C13,15N2 (m/z = 501.8–502.8) isotopic enrichment. The peak at 13 min is only observed in reactions containing MftE and SAM (+SAM +MftE) and is not observed when SAM is removed (−SAM +MftE). B, full mass spectra of the species that elutes at approximately 13 min in the extracted ion chromatograms showing isotope-sensitive peaks for the [M + H]+ at m/z 487.1928, 496.2165, and 502.2297 with unlabeled MftA, [13C8,15N]Tyr30 MftA, or [13C13,15N2]29VY30 MftA. C, HCD fragmentation mass spectra of the [M + H]+ parent ion peak in the mass spectra shown in B. Possible structures for the fragments are shown in supplemental Fig. S5. D and E, the two possible structures and theoretical masses of the Marfey's reagent-derivatized VY* dipeptide based on the HCD fragmentation results with the natural abundance and isotopically enriched MftA peptides.

The regiochemistry of the modification, however, remains unresolved. There are three positions where Marfey's reagent can react on Tyr*. We ruled out the hydroxyl of the residue because we observe a fragment corresponding to loss of H2O from Tyr* with unlabeled, [13C9,15N]Tyr30, and [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA at m/z values of 469.1822, 478.2061, and 484.2193. We note that Tyr* is an enamide, which although not as reactive as an enamine is still nucleophilic and can react with Marfey's reagent to alkylate the α-carbon. It is also possible that alkylation takes place at the β-carbon. Because the MS data do not distinguish between these in the foregoing discussion, Fig. 8 shows both the β-carbon (D) and α-carbon (E) adducts, and supplemental Fig. S5 shows the assignment of the fragments.

To further probe this unexpected reactivity between Marfey's reagent and the VY* product, we first incubated the VY* dipeptide with PITC and then treated the PITC-modified VY* with Marfey's reagent. The extracted ion chromatograms in Fig. 9A show a peak with a retention time of approximately 16 min in each of the spectra that is consistent with the theoretical m/z corresponding to [M + H]+ of the unlabeled or the isotopically enriched VY* containing both PITC and Marfey's reagents. Inspection of the mass spectra reveals that the observed m/z of each species is within 3.5 ppm error of the theoretical m/z of each PITC-Marfey's reagent-modified VY* dipeptide (Fig. 9B). The molecular ion peaks were subjected to HCD fragmentation (Fig. 9C). Supplemental Fig. S6 shows the structures that are most consistent with the ions. As for the VY* dipeptide modified by Marfey's reagent alone, the peaks with m/z values of 343.1032 and 388.1246 in the unlabeled VY* PITC-Marfey's reagent modified product and the corresponding peaks in the isotopically enriched product are consistent with Marfey's reagent reacting with the oxidatively decarboxylated tyrosine instead of the valine. The data clearly show that the peptide is modified by PITC at the N terminus and Marfey's reagent at the decarboxylated tyrosine. As noted above, we cannot distinguish between modification at the α- or β positions, and so both possibilities are shown in the figure (Fig. 9, D and E).

FIGURE 9.

PITC and Marfey's reagent derivatization of the VY* dipeptide isolated from reactions containing natural abundance MftA, [13C9,15N]Tyr30 MftA, or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA. A, a new peak (●) is observed at 16.5 min in the extracted ion chromatograms for PITC- and Marfey's reagent-derivatized VY* dipeptide at the expected m/z for unlabeled (m/z = 621.8–622.8), 13C8,15N (m/z = 630.8–631.8), or 13C13,15N2 (m/z = 636.8–637.8). B, zoomed in mass spectra of 16.5 min showing peaks at the expected m/z for unlabeled (370.1572), [13C8,15N]Tyr30 (379.1811), and [13C13,15N2]29VY30 (385.1950) MftA. A background peak at 637.310 is present in all samples and does not change upon isotopic substitution. C, HCD fragmentation mass spectra of the [M + H]+ parent ion peak in the mass spectra shown in B showing fragments consistent with the adduct. D and E, the two possible structures and theoretical masses of the PITC- and Marfey's reagent-derivatized VY* dipeptide showing the expected masses corresponding to the unlabeled (370.1589), [13C8,15N]Tyr30 (379.1828), and [13C13,15N2]29VY30 (385.1966). The theoretical m/z values are within 4.5 ppm of the experimentally determined values. The two structures differ in the regiochemistry of Marfey's reagent addition as discussed in the text.

MftB Is Not Required for the Reaction Catalyzed by MftE

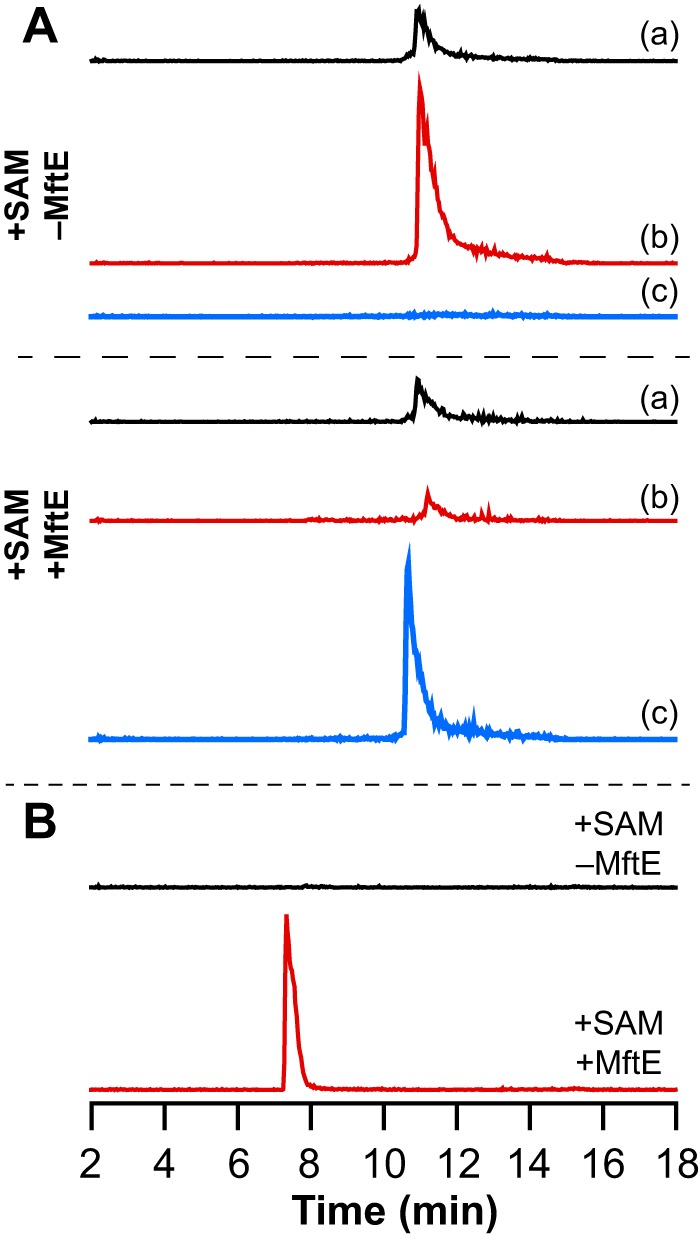

It has been established that MftC catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of MftA in an MftB-dependent manner (13, 14). Because MftB interacts with MftA, it is possible that MftE functions in an MftB-dependent manner similar to the activity observed with MftC. To probe whether MftE requires the presence of MftB to catalyze the hydrolysis of the oxidatively decarboxylated MftA, reactions were set up as described below in the absence of the MftE. In these experiments, after an initial 6-h incubation of MftA with MftB and MftC, MftB and MftC were removed. The reaction was split into two equal aliquots, and MftE was added to one. Both were incubated for an additional 3 h and analyzed for the formation of the VY* dipeptide by UHPLC-MS. Fig. 10A shows that the oxidatively decarboxylated MftA was generated by MftC in the presence of MftB, SAM, and reductant and in the absence of MftE, and there is no species in the extracted ion chromatogram corresponding to MftA(1–28) (Fig. 10A) or to the VY* dipeptide (Fig. 10B) after the 3-h incubation postfiltration. However, UHPLC-MS analysis of reactions that contained MftE shows that MftE catalyzes the hydrolysis of the oxidatively decarboxylated MftA peptide forming the both MftA(1–28) (Fig. 10A) and the VY* dipeptide (Fig. 10B). This lack of MftB requirement contrasts with activity of MftC, which is dependent on MftB (13, 14). Therefore, MftE catalyzes the cleavage of the peptide only after the MftB-dependent decarboxylation of MftA has taken place.

FIGURE 10.

MftB is not required for hydrolysis of the oxidatively decarboxylated MftA peptide to form the VY* by MftE. A, extracted ion chromatograms corresponding to the MftA peptide isolated from reactions where MftE was either omitted (+SAM −MftE) or present (+SAM +MftE) after in situ generation of the oxidatively decarboxylated MftA peptide. Chromatogram a corresponds to unmodified MftA (m/z = 1660.5–1661.5), chromatogram b corresponds to oxidatively decarboxylated MftA (m/z = 1637.5–1638.5), and chromatogram c corresponds to MftA(1–28) (m/z = 1529.5–1530.5). Each peptide elutes at approximately 11 min when present. The MftA(1–28) peptide is only generated upon incubating the filtrate with MftE. B, extracted ion chromatogram corresponding to the VY* dipeptide (m/z = 234.5–235.5) shows that the VY* dipeptide is generated in the reaction containing MftE (+SAM +MftE) in the absence of MftB but not in the reaction where the MftE was omitted (+SAM −MftE).

Summary

The biochemical and mass spectral data shown here collectively show that MftE catalyzes the cleavage of MftA* to form VY* and MftA(1–28).

Discussion

Members of the amidohydrolase superfamily catalyze hydrolysis of a diverse array of substrates (26). Within the vast superfamily, there are examples of enzymes, such as renal dipeptidase, that catalyze the hydrolysis of peptide amide bonds (27, 28). However, to our knowledge, MftE is unique in catalyzing the hydrolysis of a peptide bond in a 30-amino acid modified protein. Importantly, the enzyme does not catalyze the hydrolysis of the amide bond on the unmodified MftA peptide precursor, strongly supporting its role as downstream of MftB and MftC in the biosynthetic pathway involving MftA.

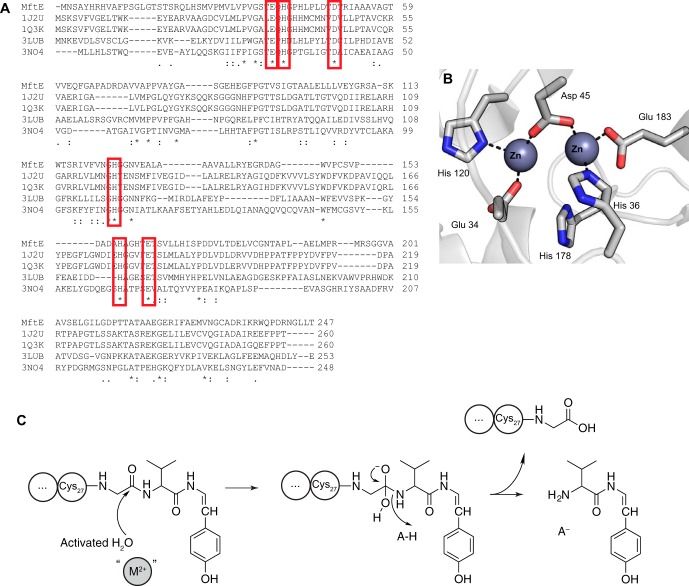

A search of the Protein Data Bank with the sequence of MftE reveals similarity to creatininase homologs whose structures are known. Sequence alignments (Fig. 11A) and mapping of conserved residues onto the structures of a creatinine amidohydrolase show that MftE retains the active site residues that bind the divalent cations that activate a water molecule for hydrolysis and to stabilize the oxyanion intermediate generated during catalysis (Fig. 11B) (25, 29). On the basis of sequence conservation, we postulate that MftE utilizes a similar catalytic mechanism (Fig. 11C).

FIGURE 11.

A, amino acid sequence alignments among MftE and creatininase homologs with known structures. Single, fully conserved residues are indicated with asterisk. Conservation between groups with strongly similar properties is indicated with a colon, and conservation between groups with weakly similar properties is indicated by a period. The red boxes highlight the His, Glu, and Asp residues that are conserved in MftE and map to residues that are structurally observed to coordinate the two divalent metals in the structures of the creatininase homologs (Protein Data Bank codes 1J2U, 1O3K, 3LUB, and 3NO4). B, active site of creatininase from Pseudomonas putida (Protein Data Bank code 1J2U) showing the six conserved residues highlighted in the sequence alignment (25). C, proposed catalytic mechanism of MftE based on the function of homologous creatininase enzymes. The results of ICP-MS are consistent with MftE requiring at least one divalent metal ion (M2+).

The bioinformatics investigation by Haft (19) first identified a subset of microorganisms that cluster mftA, mftB, mftC, mftD, mftE, and mftF genes in their chromosomes. It was speculated that the MftA peptide that is encoded by the mftA gene in these organisms is the precursor to a novel redox metabolite analogous to PQQ (19). We have recently shown that MftB and MftC are required for the oxidative decarboxylation of the Tyr residue at the C terminus of MftA (13). Here we showed that the creatininase homolog MftE, which is encoded by the mftE gene, catalyzes the second step in the maturation of MftA. Although at this point the structure and biological function of the metabolite that is ultimately derived from MftA are not known, the reactivity of the modified Tyr residue may foreshadow both. Studies are now underway to characterize the remaining two proteins encoded by the genes in the mft cluster to complete the in vitro reconstitution of the biosynthetic pathway and identify the novel natural product that builds on VY*.

Experimental Procedures

Cloning of the mftE

The LI98_07105 gene that encodes for the creatininase homolog, referred to as mftE, was PCR-amplified from the M. smegmatis ATCC 700084 genome using the forward primer 5′-AAAAAAGCTAGCATGAATTCGGCTTACCATCGGCACG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-AAAAAACTCGAGTCATGTCAGCAATCCGTTCCGG-3′. The italicized sequences show engineered NheI and XhoI restriction sites in the forward and reverse primers, respectively, and the stop codon in the reverse primer is underlined. The purified PCR product was subsequently digested with NheI and XhoI and ligated into pET28JT vector (30) that was similarly digested with NheI and XhoI for recombinant expression of protein containing a tobacco etch virus protease cleavable N-terminal His6 tag. Standard Sanger sequencing at the University of Michigan DNA Sequencing Core confirmed the sequence of the mftE-pET28JT plasmid.

Expression of Recombinant MftE

E. coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) cells were transformed with the mftE-pET28JT plasmid. Large scale cultures containing Lennox broth growth medium (12 × 1 liter in 2-liter baffle flasks) supplemented with 34 μg/ml kanamycin and 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol were inoculated with 0.1 liter of mftE-pET28JT Rosetta 2 (DE3) overnight culture/liter of fresh medium and grown at 37 °C. The mftE gene was induced upon the addition of isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside to a final concentration of 0.1 mm when the A600 nm reached ∼0.8. Cells were allowed to express the MftE at 37 °C. After 5 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 × g, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

Purification of the MftE

The purification of MftE was performed at 4 °C. Cells (∼15 g) were suspended in ∼0.5 liter of 0.05 m potassium phosphate (pH 7.4), 0.5 m KCl, 0.05 m imidazole, and 1 mm PMSF and lysed using a Branson digital sonifier operated at 50% amplitude. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 35 min at 4 °C prior to loading on a 5-ml HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) that had been charged with nickel sulfate and equilibrated in 0.05 m potassium phosphate (pH 7.4) containing 0.5 m KCl and 0.05 m imidazole. After loading the clarified lysate, the column was washed with 15 column volumes of equilibration buffer, and MftE was eluted with a linear gradient from 0.05 to 0.5 m imidazole over 20 column volumes. Fractions containing the MftE were identified by SDS-PAGE, pooled, and dialyzed overnight against 0.02 m Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 0.15 m NaCl, and 10 mm DTT at 4 °C with two changes of the dialysis buffer. After dialysis, the MftE was concentrated to a minimal volume (∼1.5 ml), flash frozen in small aliquots, and stored at −80 °C. The concentration of the MftE was determined by the Bradford method with BSA as the standard but corrected for the actual amino acid concentration as described below.

Purification of MftB and MftC

The MftB and MftC proteins were expressed and purified as described previously (13).

Amino Acid Analysis

MftE was subjected to amino acid analysis to determine the accuracy of the concentration measured by the Bradford method. A 0.1-ml aliquot of concentrated protein was desalted to 10 mm NaOH using an Illustra NICK column (GE Healthcare). The concentration of the eluent was determined by the Bradford method with BSA as the standard before being flash frozen and analyzed at the Molecular Structure Facility at the University of California-Davis. The analysis was performed on two independent preparations of the enzyme in triplicate. The correction factor was applied to all Bradford method-determined protein concentrations used in this investigation.

Analysis of Metal Ion Content in MftE

The metal ion content of the MftE was determined by ICP-MS at the Center for Water, Ecosystems, and Climate Science in the Department of Geology and Geophysics at the University of Utah. Concentrated protein was diluted in 1% (v/v) trace metals grade nitric acid to a final concentration of 11 μm. Metal ion analysis was conducted on MftE from two independent purifications in triplicate and averaged.

Synthesis of Unlabeled, [13C9,15N]Tyr30, and [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA Peptides

All MftA peptides were synthesized on a 0.025-mmol scale by solid phase peptide synthesis methodology using a PS3 peptide synthesizer (Protein Technologies Inc.) following the manufacturer's coupling protocol using Fmoc chemistries. All protected Fmoc-amino acids were purchased from Protein Technologies Inc. The Fmoc-[13C9,15N]Tyr O-tert-butyl ether (-OtBu) and Fmoc-[13C5,15N]Val were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc. In brief, 0.15 g of 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin 100–200 mesh (ChemPep) was loaded with either Fmoc-Tyr-OtBu or Fmoc-[13C9,15N]Tyr-OtBu (∼0.2 mmol/g of resin) to obtain either unlabeled or isotopically enriched MftA, respectively. Prior to loading the Fmoc-Tyr onto the resin, the resin was washed three times with 5 ml of DMF and three times with 5 ml of dichloromethane (DCM). Either the unlabeled or 13C9,15N-enriched Fmoc-Tyr-OtBu (0.03 mmol) was dissolved in 1 ml of 1:1 DMF/DCM containing 0.15 mmol of diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA). The Fmoc-Tyr/DIPEA solution was added to the 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin and incubated at room temperature to load the resin with the C-terminal residue of MftA. The resin was gently agitated every 5–10 min. After 1 h, the Fmoc-Tyr/DIPEA solution was removed, and the resin was washed three times with 5 ml of DCM. The remaining sites on the 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin were capped by slowly washing the resin with 20 ml of 17:2:1 DCM:methanol:DIPEA. After capping, the Fmoc-Tyr-loaded resin was washed three times with 5 ml of DCM and three times with 5 ml of DMF and transferred to the reaction vessel.

All Fmoc-amino acids, including the Fmoc-[13C5,15N]Val (0.15 mmol, 5 eq) were coupled by in situ activation with N-[(dimethylamino)-1H-1,2,3-triazolo-[4,5-b]pyridin-1-ylmethylene]-N-methylmethanaminium hexafluorophosphate N-oxide (0.15 mmol, 5 eq; ChemPep) in 0.6 m N-methylmorpholine. To obtain the peptides with a free C-terminal carboxylic acid from the resin, peptides were deprotected and cleaved from the resin by adding 6 ml of cleavage solution (92.5% (v/v) TFA, 2.5% (v/v) water, 2.5% (v/v) ethane dithiol, and 2.5% (v/v) triisopropyl silane) at room temperature with constant mixing. After 2 h, the cleavage reaction was filtered, and the peptide was precipitated in ∼30 ml of ice-cold diethyl ether. Centrifugation of the ether suspension at 5000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C pelleted the precipitated peptide, allowing the supernatant to be decanted. The peptide was washed three times with ice-cold ether and centrifuged at 5000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was discarded. After the final wash, the peptide was dried under vacuum for 2 h. The dried peptide was subsequently dissolved in ∼10–20 ml of 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate (pH 7.7), frozen in liquid nitrogen, and lyophilized to dryness. Once dried, each crude peptide was dissolved to a final concentration of 7 mg/ml in 0.05 m Tris·HCl (pH 8.0) and 10 mm DTT under anaerobic conditions (Coy Laboratories anaerobic chamber with 95% N2, 5% H2 atmosphere), aliquoted, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. The three synthetic peptides lacked the N-terminal methionine residue.

UHPLC-MS Analysis of the MftA Peptides

The purity of the dissolved crude unlabeled and [13C9,15N]Tyr30 peptides was determined as described previously (13).The purity of [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA was analyzed by LC-MS using an LTQ OrbiTrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher) connected to a Vanquish UHPLC with a diode array detector (Thermo Fisher). An aliquot (1 μl) of the concentrated (7 mg/ml) MftA peptide was injected onto an Accucore C8 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 2.6-μm particle size; Thermo Fisher) pre-equilibrated in 5% buffer B (buffer A, 0.1% (v/v) TFA; buffer B, acetonitrile with 0.1% (v/v) TFA). The peptides were eluted at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min with the following method: 0–2.5 min, 5% buffer B; 2.5–11.5 min, 5–70% buffer B; 11.5–11.6 min, 70–100% buffer B; 11.6–16.6 min, 100% buffer B; 16.6–16.7 min, 100–5% buffer B; 16.7–21.7 min, 5% buffer B.

All mass spectral data in this investigation were collected by operating the LTQ OrbiTrap XL mass spectrometer in positive ion mode detecting with the FT analyzer set to a resolution of 100,000, one microscan, and 200-ms maximum injection time. All mass spectrometry data were analyzed using Xcalibur software (Thermo Fisher), and the deconvoluted spectra were generated from the raw data using Xtract software (Thermo Fisher).

MftA Modification Reactions

Reactions (0.2 ml) contained 0.05 m Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mm DTT, 10 mm dithionite, 0 or 1 mm SAM (enzymatically synthesized and purified as described previously (31)), 0.7 mg/ml crude MftA (unlabeled, [13C9,15N]Tyr30, or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA), 0.05 mm MftB, 0.05 mm MftC, and 0 or 0.05 mm MftE. Reactions were set up and incubated at room temperature in an anaerobic environment (Coy Laboratories anaerobic chamber with 95% N2, 5% H2 atmosphere). After 9 h, the reactions were passed through a 10-kDa molecular mass cutoff spin concentrator centrifuged at 8000 × g for 15 min to remove the enzymes prior to UHPLC-MS analysis. The reactions were initiated upon the addition of dithionite.

UHPLC-MS Analysis of Reactions

Reactions were analyzed by UHPLC-MS using an LTQ OrbiTrap XL mass spectrometer connected to a Vanquish UHPLC with a diode array detector set up as described above. Peptide modification was detected by injecting 30 μl onto a Hypersil Gold C4 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 1.9-μm particle size; Thermo Fisher) pre-equilibrated in 5% buffer B (buffer A, 0.1% (v/v) TFA; buffer B, acetonitrile with 0.1% (v/v) TFA). The peptides were eluted at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min with the following method: 0–1 min, 5% buffer B; 1–11.5 min, 5–70% buffer B; 11.5–11.6 min, 70–100% buffer B; 11.6–16.6 min, 100% buffer B; 16.6–16.7 min, 100–5% buffer B; 16.7–21.7 min, 5% buffer B.

The presence of the valine-modified tyrosine (VY*) dipeptide was monitored by injecting 30 μl of the reaction mixture onto an Accucore C8 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 2.6-μm particle size) pre-equilibrated in 5% buffer B (buffer A, 0.1% (v/v) TFA; buffer B, acetonitrile with 0.1% (v/v) TFA). The peptides were eluted at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min with the following method: 0–2.5 min, 5% buffer B; 2.5–11.5 min, 5–70% buffer B; 11.5–11.6 min, 70–100% buffer B; 11.6–16.6 min, 100% buffer B; 16.6–16.7 min, 100–5% buffer B; 16.7–21.7 min, 5% buffer B.

HCD Fragmentation of VY* Dipeptide

Aliquots (60 μl) from the reactions containing the VY* dipeptide set up as described above were injected onto a Hypersil Gold C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 1.9-μm particle size; Thermo Fisher) pre-equilibrated in 0% buffer B (buffer A, 50 mm ammonium acetate (pH 6.0); buffer B, acetonitrile with 0.1% (v/v) TFA). The peptides were eluted at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min with the following method: 0–1 min, 0% buffer B; 1–10.5 min, 0–20% buffer B; 10.5–10.6 min, 20–100% buffer B; 10.6–15.6 min, 100% buffer B; 15.6–15.7 min, 100–0% buffer B; 15.7–20.7 min, 0% buffer B. The mass spectrometer was set up to isolate the mass envelope corresponding to the [M + H]+ ion of the VY* product in the HCD cell using an isolation width of 1.0 m/z and 0.1-ms activation time. Each VY* was fragmented with a collision energy of 35%, and the fragments were detected using the FT analyzer, which was set up as described above.

Chemical Modification of VY* Dipeptide

Reactions containing all components or where only SAM was omitted were set up as described above with the natural abundance, [13C9,15N]Tyr30, or [13C14,15N2]29VY30 MftA peptides in a final volume of 0.3 ml. After 9 h, the reactions were transferred to a 10-kDa molecular mass cutoff spin concentrator and centrifuged at 8000 × g for 15 min to remove the enzymes prior to chemical modification by PITC and/or Marfey's reagent.

An aliquot (80 μl) of filtrate was flash frozen and lyophilized to dryness prior to modification by PITC. The dried aliquot was dissolved in 0.1 ml of a 10:5:2:3 mixture of acetonitirle:pyridine:triethylamine:water prior to addition of 5 μl of PITC (Thermo Scientific). The reaction was subsequently flash frozen after incubating at room temperature for 30 min and lyophilizing to dryness. Dried samples were dissolved in 80 μl of 50 mm ammonium acetate (pH 6.0) and centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 5 min prior to UHPLC-MS analysis.

An aliquot (80 μl) of filtrate was diluted with 0.2 ml of 1% (w/v) Marfey's reagent in acetone, and 40 μl of 1 m sodium bicarbonate was added to the mixture. The reaction mixture was incubated at 40 °C for 2 h and subsequently quenched with 20 μl of 2 m HCl prior to UHPLC-MS analysis.

To modify the VY* dipeptide with both PITC and Marfey's reagent, an aliquot (80 μl) of the filtrate was modified with PITC as described above. After lyophilization, the dried PITC-modified peptide was dissolved in 80 μl of 50 mm ammonium acetate (pH 6.0) and incubated with Marfey's reagent as described above.

UHPLC-MS and UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis of Chemically Modified VY*

Aliquots of the PITC- (20 μl), Marfey's reagent- (50 μl), and PITC-Marfey's reagent (50 μl)-modified VY* products were injected onto a Hypersil Gold C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 1.9-μm particle size) pre-equilibrated in 5% buffer B (buffer A, 50 mm ammonium acetate (pH 6.0); buffer B, acetonitrile with 0.1% (v/v) TFA). The products were eluted at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min with the following method: 0–1 min, 5% buffer B; 1–20.6 min, 0–100% buffer B; 20.6–25.6 min, 100% buffer B; 25.6–25.7 min, 100–5% buffer B; 25.7–30.7 min, 5% buffer B. The mass spectrometer was set up with two scan events, the first to collect both the full mass spectrum and the second to isolate the mass envelope corresponding to the [M + H]+ ion of the PITC-VY*, Marfey's reagent-VY*, or PITC-Marfey's reagent-VY* product in the HCD cell using an isolation width of 1.0 m/z and 0.1-ms activation time. Each the PITC-modified VY* products was fragmented with a collision energy of 25%. The doubly modified VY* products were fragmented with a collision energy of 35%. The full mass spectra and fragments were detected using the FT analyzer, which was set up as described above.

MftB Requirement for MftE Activity

Reactions to synthesize the natural abundance or isotopically enriched oxidatively decarboxylated MftA peptides were set up as described above in the absence of MftE to a final volume of 0.4 ml. After incubating for 6 h, the reactions were passed through a 10-kDa molecular mass cutoff spin filter to remove both MftB and MftC. The filtrates were split into two equal fractions (0.1 ml), and the MftE was added to one aliquot of filtrate to a final concentration of 0.05 mm. Each aliquot was incubated at room temperature for an additional 3 h, quenched via filtration, and analyzed for the presence of the VY* dipeptide by UHPLC-MS as described above.

Author Contributions

N. A. B. and V. B. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. N. A. B. performed all of the experiments described in the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by NIGMS, National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM120638 and GM72623 (to V. B.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6.

- RiPP

- ribosomally synthesized post-translationally modified peptide

- ATCC

- American Type Culture Collection

- 5′-dAdo•

- 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical

- DCM

- dichloromethane

- DMF

- N,N-dimethylformamide

- DIPEA

- diisopropylethylamine

- Fmoc

- fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl

- HCD

- higher energy collision dissociation

- ICP

- inductively coupled plasma

- Marfey's reagent

- 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-l-alanine amide

- PITC

- phenyl isothiocyanate

- PQQ

- pyrroloquinoline quinone

- SAM

- S-adenosyl-l-methionine

- -OtBu

- O-tert-butyl ether

- UHPLC

- ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography

- VY*

- valine-oxidatively decarboxylated tyrosine

- FT

- Fourier transform.

References

- 1. Fischbach M. A., and Walsh C. T. (2006) Assembly-line enzymology for polyketide and nonribosomal peptide antibiotics: logic, machinery, and mechanisms. Chem. Rev. 106, 3468–3496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Finking R., and Marahiel M. A. (2004) Biosynthesis of nonribosomal peptides. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58, 453–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnison P. G., Bibb M. J., Bierbaum G., Bowers A. A., Bugni T. S., Bulaj G., Camarero J. A., Campopiano D. J., Challis G. L., Clardy J., Cotter P. D., Craik D. J., Dawson M., Dittmann E., Donadio S., et al. (2013) Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide natural products: overview and recommendations for a universal nomenclature. Nat. Prod. Rep. 30, 108–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ono K., Okajima T., Tani M., Kuroda S., Sun D., Davidson V. L., and Tanizawa K. (2006) Involvement of a putative [Fe-S]-cluster-binding protein in the biogenesis of quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 13672–13684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nakai T., Ito H., Kobayashi K., Takahashi Y., Hori H., Tsubaki M., Tanizawa K., and Okajima T. (2015) The radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine enzyme QhpD catalyzes sequential formation of intra-protein sulfur-to-methylene carbon thioether bonds. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 11144–11166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flühe L., Knappe T. A., Gattner M. J., Schäfer A., Burghaus O., Linne U., and Marahiel M. A. (2012) The radical SAM enzyme AlbA catalyzes thioether bond formation in subtilosin A. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 350–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flühe L., Burghaus O., Wieckowski B. M., Giessen T. W., Linne U., and Marahiel M. A. (2013) Two [4Fe-4S] clusters containing radical SAM enzyme SkfB catalyze thioether bond formation during the maturation of the sporulation killing factor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 959–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bruender N. A., and Bandarian V. (2016) SkfB abstracts a hydrogen atom from Cα on SkfA to initiate thioether cross-link formation. Biochemistry 55, 4131–4134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruender N. A., Wilcoxen J., Britt R. D., and Bandarian V. (2016) Biochemical and spectroscopic characterization of a radical S-adenosyl-L-methionine enzyme involved in the formation of a peptide thioether cross-link. Biochemistry 55, 2122–2134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wieckowski B. M., Hegemann J. D., Mielcarek A., Boss L., Burghaus O., and Marahiel M. A. (2015) The PqqD homologous domain of the radical SAM enzyme ThnB is required for thioether bond formation during thurincin H maturation. FEBS Lett. 589, 1802–1806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schramma K. R., Bushin L. B., and Seyedsayamdost M. R. (2015) Structure and biosynthesis of a macrocyclic peptide containing an unprecedented lysine-to-tryptophan crosslink. Nat. Chem. 7, 431–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barr I., Latham J. A., Iavarone A. T., Chantarojsiri T., Hwang J. D., and Klinman J. P. (2016) The pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) biosynthetic pathway: demonstration of de novo carbon-carbon cross-linking within the peptide substrate (PqqA) in the presence of the radical SAM enzyme (PqqE) and its peptide chaperone (PqqD). J. Biol. Chem. 291, 8877–8884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bruender N. A., and Bandarian V. (2016) The radical S-adenosyl-L-methionine enzyme MftC catalyzes an oxidative decarboxylation of the C-terminus of the MftA peptide. Biochemistry 55, 2813–2816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khaliullin B., Aggarwal P., Bubas M., Eaton G. R., Eaton S. S., and Latham J. A. (2016) Mycofactocin biosynthesis: modification of the peptide MftA by the radical S-adenosylmethionine protein MftC. FEBS Lett. 590, 2538–2548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Freeman M. F., Gurgui C., Helf M. J., Morinaka B. I., Uria A. R., Oldham N. J., Sahl H. G., Matsunaga S., and Piel J. (2012) Metagenome mining reveals polytheonamides as posttranslationally modified ribosomal peptides. Science 338, 387–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morinaka B. I., Vagstad A. L., Helf M. J., Gugger M., Kegler C., Freeman M. F., Bode H. B., and Piel J. (2014) Radical S-adenosyl methionine epimerases: regioselective introduction of diverse D-amino acid patterns into peptide natural products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 8503–8507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sofia H. J., Chen G., Hetzler B. G., Reyes-Spindola J. F., and Miller N. E. (2001) Radical SAM, a novel protein superfamily linking unresolved steps in familiar biosynthetic pathways with radical mechanisms: functional characterization using new analysis and information visualization methods. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 1097–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Broderick J. B., Duffus B. R., Duschene K. S., and Shepard E. M. (2014) Radical S-adenosylmethionine enzymes. Chem. Rev. 114, 4229–4317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haft D. H. (2011) Bioinformatic evidence for a widely distributed, ribosomally produced electron carrier precursor, its maturation proteins, and its nicotinoprotein redox partners. BMC Genomics 12, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goosen N., Horsman H. P., Huinen R. G., and van de Putte P. (1989) Acinetobacter calcoaceticus genes involved in biosynthesis of the coenzyme pyrrolo-quinoline-quinone: nucleotide sequence and expression in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 171, 447–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Velterop J. S., Sellink E., Meulenberg J. J., David S., Bulder I., and Postma P. W. (1995) Synthesis of pyrroloquinoline quinone in vivo and in vitro and detection of an intermediate in the biosynthetic pathway. J. Bacteriol. 177, 5088–5098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Toyama H., Chistoserdova L., and Lidstrom M. E. (1997) Sequence analysis of pqq genes required for biosynthesis of pyrroloquinoline quinone in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 and the purification of a biosynthetic intermediate. Microbiology 143, 595–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tsuru D., Oka I., and Yoshimoto T. (1976) Creatinine decomposing enzymes in Pseudomonas putida. Agric Biol. Chem. 40, 1011–1018 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yoshimoto T., Oka I., and Tsuru D. (1976) Creatine amidinohydrolase of Pseudomonas putida: crystallization and some properties. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 177, 508–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beuth B., Niefind K., and Schomburg D. (2003) Crystal structure of creatininase from Pseudomonas putida: a novel fold and a case of convergent evolution. J. Mol. Biol. 332, 287–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seibert C. M., and Raushel F. M. (2005) Structural and catalytic diversity within the amidohydrolase superfamily. Biochemistry 44, 6383–6391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cummings J. A., Nguyen T. T., Fedorov A. A., Kolb P., Xu C., Fedorov E. V., Shoichet B. K., Barondeau D. P., Almo S. C., and Raushel F. M. (2010) Structure, mechanism, and substrate profile for Sco3058: the closest bacterial homologue to human renal dipeptidase. Biochemistry 49, 611–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Adachi H., Kubota I., Okamura N., Iwata H., Tsujimoto M., Nakazato H., Nishihara T., and Noguchi T. (1989) Purification and characterization of human microsomal dipeptidase. J. Biochem. 105, 957–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoshimoto T., Tanaka N., Kanada N., Inoue T., Nakajima Y., Haratake M., Nakamura K. T., Xu Y., and Ito K. (2004) Crystal structures of creatininase reveal the substrate binding site and provide an insight into the catalytic mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 337, 399–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thoden J. B., and Holden H. M. (2005) The molecular architecture of human N-acetylgalactosamine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32784–32791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McCarty R. M., Krebs C., and Bandarian V. (2013) Spectroscopic, steady-state kinetic, and mechanistic characterization of the radical SAM enzyme QueE, which catalyzes a complex cyclization reaction in the biosynthesis of 7-deazapurines. Biochemistry 52, 188–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.