Abstract

Background

Continuing education (CE) is intended to facilitate clinicians' skills and knowledge in areas of practice, such as administration and interpretation of outcome measures.

Objective

To evaluate the long-term effect of CE on prosthetists' confidence administering outcome measures and their perceptions of outcomes measurement in clinical practice.

Design

Pretest–posttest survey methods

Methods

Sixty-six prosthetists were surveyed before, immediately after, and two years after outcomes measurement education and training. Prosthetists were grouped as routine or non-routine outcome measures users, based on experience reported prior to training.

Results

On average, prosthetists were just as confident administering measures 1-2 years after CE as they were immediately after CE. Twenty percent of prosthetists, initially classified as non-routine users, were subsequently classified as routine users at follow-up. Routine and non-routine users' opinions differed on whether outcome measures contributed to efficient patient evaluations (79.3% and 32.4%, respectively). Both routine and non-routine users reported challenges integrating outcome measures into normal clinical routines (20.7% and 45.9%, respectively).

Conclusion

CE had a long-term impact on prosthetists' confidence administering outcome measures and may influence their clinical practices. However, remaining barriers to using standardized measures need to be addressed to keep practitioners current with evolving practice expectations.

Keywords: Allied Health Occupations, Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice, Outcome Assessment, Professional Education, Surveys and Questionnaires

Introduction

Use of standardized outcome measures has increasingly become an expectation in the provision of clinical care.1–3 Nevertheless, professionals across a range of health disciplines have reported challenges integrating outcomes measurement into their daily routines.2,4–8 A lack of fundamental knowledge regarding measure selection, administration, and/or interpretation has been often cited as a primary barrier to clinical use of outcome measures.2,9–11 Education specific to outcomes measurement has been advocated as a means to increase practitioners' familiarity with available measures and promote their use in clinical care.2,3,11–14 However, outcomes measurement training has only recently become an educational requirement for Orthotics and Prosthetics (O&P). For O&P practitioners whose professional training did not include outcomes measurement, continuing education (CE) courses is a way to acquire the knowledge and skills necessary to use outcome measures in clinical practice.3

Continuing education is generally acknowledged as an effective means to alter practitioners' attitudes, knowledge, and skills.15–17 For example, CE focused on developing health professionals' research skills was shown to increase experience and confidence in performing activities like finding literature, reviewing literature, and analyzing study results.18 CE therefore seems well suited to addressing both the philosophical and practical barriers to use of outcome measures in clinical care.19–21 Despite the potential for CE to positively affect outcomes measurement practices in O&P, little evidence exists to demonstrate focused outcomes measurement education and training can facilitate practitioners' use of standardized outcome measures.

In a prior study,5 we developed a mixed-format CE course to familiarize prosthetists with administration of two physical performance measures that have been advocated for use with prosthetic patients. Prosthetists were trained to administer the measures using didactic and interactive teaching strategies, provided with videos and written materials for later reference, and encouraged to incorporate the new knowledge into their daily clinical practices. Those that attended the course were surveyed about their confidence administering the measures before and immediately after training. Results showed that prosthetists' confidence improved significantly with the provided CE.5 While the observed short-term effects of this course are encouraging, the long-term effectiveness of outcomes measurement CE (i.e., whether focused training can lead to increased confidence and use of measures) is unknown.

The primary aim of this research was to determine whether practitioners' confidence in administering outcome measures was retained long-term after CE. Secondarily, we wanted to assess if practitioners' use of outcome measures had changed, relative to before they took the CE course. Lastly, we wanted to assess participants' perceptions of outcomes measurement, so as to identify barriers that may still exist after the need for knowledge is addressed through CE. We hypothesized that practitioners that routinely used the selected outcome measures after CE would maintain confidence in their abilty to administer them. We also hypothesized that prosthetists would use the selected performance measures with patients more often after the CE course, as compared to before training.

Methods

Prosthetists that participated in outcomes measurement courses5 were surveyed 1-2 years after training to assess their perceived ability to administer performance-based outcome measures included in the CE course. Further, prosthetists were asked about their perceptions of the benefits and barriers to outcomes measurement. All 79 prosthetists that completed a CE course in the prior study5 were sent the follow-up survey. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by a University of Washington institutional review board.

Training

Details regarding recruitment, training, and evaluation procedures were previously reported.5 Briefly, CE courses were designed to educate prosthetists on the rationale, administration, and interpretation of two performance-based measures, the Timed Up and Go (TUG)22 and the Amputee Mobility Predictor (AMP).23 The 3-hour, in-person course included didactic (i.e., presentation, written instructions, video, and discussion), demonstration, and role-play instructional techniques. Didactic instruction included basic outcomes measurement theory, rationale for using each measure with specific patients, and strategies for administering measures in clinical settings. Prosthetists practiced setting up, assessing, scoring, and interpreting the measures, while study investigators provided verbal and tactile feedback. For example, investigators demonstrated with prosthetists how to position the patient for testing and apply the appropriate amount of force to the patient's sternum in the nudge test (item 10 on the AMP). Each prosthetist also received written instructions and videos to allow them additional exposure to the content after the course.24

Surveys

Custom surveys were developed by the investigators to evaluate prosthetists' perceptions regarding outcome measures at three points: immediately before training (pre-training, Appendix 1), immediately after training (post-training, Appendix 2), and 1-2 years after training (follow-up, Appendix 3). All three surveys asked, “How confident are you in your current ability to administer the TUG or AMP?” and “Please estimate the time it currently takes you to administer the TUG or AMP.” The follow-up survey asked practitioners to report how often they used the TUG, AMP, or other measures with patients. The survey also asked practitioners about their perceptions of practical and philosophical issues related to use of outcome measures in clinical practice (e.g., perceived benefits and barriers). Benefits and barriers listed in the survey were similar to surveys provided to health professionals in prior studies.2,6 Pre- and post-training surveys were administered in person before and immediately after the course. Follow-up surveys were administered by paper or computer, according to each prosthetist's preference. Paper surveys were mailed with a prepaid return envelope. Computer surveys were administered using open-source WebQ software. Non-respondents were contacted up to two times by email and once by phone to complete the follow-up survey.

Analysis

Prosthetists' responses from the follow-up survey were compared to their responses from the pre- and post-training surveys to assess the long-term effectiveness of the outcomes measurement CE. Data were analyzed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to generate descriptive results and PASW Statistics v18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois) to assess statistical comparisons between groups. As in our prior study,5 prosthetists were classified and grouped as “routine users” and “non-routine users” of standardized outcome measures. Routine users were defined as prosthetists that responded that they “often” or “always” used the TUG, AMP, or other outcome measure with their patients; while non-routine were those that responded “never”, “rarely”, or “sometimes.” Differences in demographic and professional characteristics between prosthetists that completed the CE course in the prior study and the subsample included in this study were assessed with one sample Wilcoxon Signed-Rank tests and one sample binomial or chi square goodness of fit tests. Differences between routine and non-routine users in this study were assessed with Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney and two-sided Fisher's Exact tests. Differences between prosthetists' post-training and follow-up level of confidence and administration time were evaluated using the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test. The threshold for statistical significance was set at α=0.05 and adjustments were made for multiple comparisons, as appropriate. Descriptive statistics were used to compare routine and non-routine users' perspectives about the benefits and barriers to using outcome measures in clinical practice.

Results

Sixty-six prosthetists from the prior study5 completed the follow-up survey (83.5% retention rate) and were included in this analysis (Table 1). Time to follow-up ranged from 1.11 to 2.42 years (M=1.78 years, SD=0.37). There were no significant differences in age (Z=−0.514, p=.607), years in practice (Z=−0.493, p=.622), sex (p=.845), race/ethnicity (p=.843), education (p=.655), or clinical certification (p=.829) between prosthetists that completed the post-training and follow-up surveys. Fewer than half of the prosthetists (43.9%, n=29) reported “often” or “always” using outcome measures and were subsequently classified as routine outcome measure users at follow-up; the rest (56.1%, n=37) were classified as non-routine users. There were no significant differences in age (Z=0.323, p=.747), years in practice (Z=0.363, p=.717), sex (p=.572), race/ethnicity (p=.311), education (p=.232), or clinical certification (p=.537) between routine and non-routine users (Table 1). Most practitioners (71.2%, n=47) remained consistent in their reported use of outcome measures between the pre-training and follow-up surveys. However 13 prosthetists (19.7%) changed from non-routine to routine users and 6 prosthetists (9.1%) changed from routine to non-routine users. Thus, the percent of respondents classified as routine users was higher at follow-up (43.9%, n=29 of 66), compared to pre-training (38.0%, n=30 of 79).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants (n=66 total)

| Characteristics | Routine users (n=29) | Non-routine users (n=37) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at training (years, mean and SD) | 43.4 (10.5) | 42.2 (9.5) |

| Time in clinical practice (years, mean and SD) | 16.3 (11.1) | 15.0 (10.2) |

| Sex (n and %) | ||

| Male | 23 (79.3%) | 26 (70.3%) |

| Female | 6 (20.7%) | 11 (29.7%) |

| Race/Ethnicity (n and %) | ||

| Non-Hispanic/White | 27 (93.1%) | 31 (83.8%) |

| Asian | 1 (3.4%) | 4 (10.8%) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (5.4%) |

| More than 1 race | 1 (3.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Clinical Certification (n and %) | ||

| CP | 10 (34.5%) | 8 (21.6%) |

| CPO | 18 (62.1%) | 26 (70.3%) |

| Other | 1 (3.4%) | 3 (8.1%) |

Note: percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding

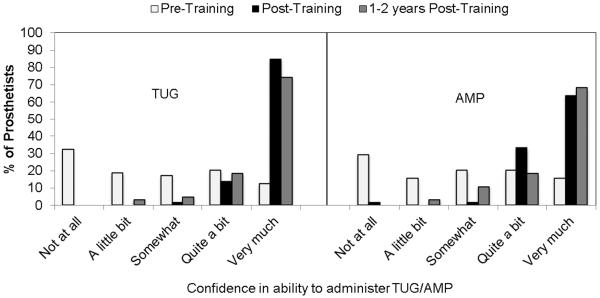

As described in the prior study, prosthetists reported significantly increased confidence administering both the TUG (Z=−6.506, p<.0001) and AMP (Z=−6.331, p<.0001) immediately after CE was provided (Figure 1).5 There were, however, no statistically significant changes in confidence administering the TUG (Z=−1.874, p=.061) or AMP (Z=−0.726, p=.468) between post-training and follow-up. While some prosthetists (28.8%, n=19) reported less confidence with one or both measures at follow-up as compared to post-training, most (63.2%, n=12 of 19) changed by only one category (e.g., they reported being “very much” confident at follow-up, compared to being “quite a bit” confident after CE). Also, the large majority of prosthetists that reported being less confident with either measure at follow-up (89.5%, n=17 of 19) were classified as non-routine users.

Figure 1.

Prosthetists' reported confidence administering the TUG and AMP before training, after training, and at 1.8 ± 0.4 years after training.

Prosthetists reported the TUG required slightly more time to administer at follow-up (4.6±3.5 min) than at post-training (4.2±3.2 min), Z=−0.526, p=.599. Conversely, the AMP required slightly less time to administer at follow-up (19.5±9.4 min), compared to post-training (20.6±7.1 min), Z=−1.726, p=.084. Although it generally took prosthetists about four times longer to administer the AMP than the TUG, more prosthetists routinely used the AMP with patients (i.e., 24.2% routinely used the TUG; 40.9% the AMP). Prosthetists' use of both measures was markedly increased at follow-up, relative to pre-training (i.e., only 3.0% and 16.7% of prosthetists routinely used the TUG and AMP, respectively, prior to training). Even more prosthetists indicated that they intended to routinely use the TUG and AMP with future patients (35.4% and 47.7%, respectively).

Prosthetists' opinions about the benefits to outcome measures varied (Table 2). Most routine users (n=89.7%, n=26 of 29) responded that outcome measures “quite a bit” or “very much” contributed to a comprehensive evaluation, whereas fewer non-routine users (56.8%, n=21 of 37) responded accordingly. The largest difference between routine and non-routine users was the belief that outcome measures contribute to an efficient patient evaluation (i.e., 79.3% [n=23 of 29] of routine users endorsed this statement, compared to only 32.4% [n=12 of 37] of non-routine users). The smallest difference between groups was the belief that outcome measures contribute to marketing efforts (37.9% [n=11 of 29] of routine users compared to 27.0% [n=10 of 37] of non-routine users). Fewer than 60% of non-routine users agreed “quite a bit” or “very much” with any of the listed benefits. The benefit most endorsed by non-routine users (59.5%, n=22 of 37) was that outcome measures `help justify clinical decisions to payors.'

Table 2.

Perceived benefits to use of outcome measures in clinical practice. Benefits are presented in order of those most often endorsed by routine users.

| In your opinion, how much do outcome measures … | Routine users (n=29) | Non-routine users (n=37) |

|---|---|---|

| Contribute to a comprehensive evaluation | 26 (89.7%) | 21 (56.8%) |

| Provide useful information | 26 (89.7%) | 18 (48.6%) |

| Help justify clinical decisions to payors | 24 (82.8%) | 22 (59.5%) |

| Contribute to an efficient evaluation | 23 (79.3%) | 12 (32.4%) |

| Help guide clinical decisions | 21 (72.4%) | 11 (29.7%) |

| Help motivate patients | 20 (69.0%) | 9 (24.3%) |

| Facilitate communication among medical professionals | 18 (62.1%) | 13 (35.1%) |

| Contribute to better patient outcomes | 18 (62.1%) | 10 (27.0%) |

| Facilitate communication with patients | 16 (55.2%) | 8 (21.6%) |

| Contribute to marketing efforts | 11 (37.9%) | 10 (27.0%) |

Prosthetists' opinions of barriers to use of outcome measures varied as well (Table 3). Non-routine users reported more barriers than routine users. While relatively few routine users (20.7%, n=6 of 29) indicated that outcome measures were “quite a bit” or “very much” difficult to integrate into their routine, more (45.9%, n=17 of 37) non-routine users responded similarly. Finally, a modest number of non-routine users (18.9%, n=7 of 37) reported that outcome measures require more effort than they are worth, while no routine user identified this issue as a barrier.

Table 3.

Perceived barriers to use of outcome measures in clinical practice. Barriers are presented in order of those most often endorsed by routine users.

| In your opinion, how much of a problem are outcome measures because they … | Routine users (n=29) | Non-routine users (n=37) |

|---|---|---|

| Are difficult to integrate into your routine | 6 (20.7%) | 17 (45.9%) |

| Are difficult to set up | 1 (3.4%) | 4 (10.8%) |

| Are difficult to administer | 1 (3.4%) | 3 (8.1%) |

| Are difficult to interpret | 1 (3.4%) | 5 (13.5%) |

| Require special training | 1 (3.4%) | 2 (5.4%) |

| Add a burden to patients | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (8.1%) |

| Are difficult to select | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (10.8%) |

| Require special knowledge | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (8.1%) |

| Require special equipment | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Require more effort than they are worth | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (18.9%) |

| Are beyond your scope of practice | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.7%) |

| Interfere with your autonomy as a provider | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (5.4%) |

Discussion

Results of this study showed that outcomes measurement CE had both an immediate and long-term effect on prosthetists' confidence and ability to administer performance-based measures. As a group, prosthetists were as confident administering the TUG and AMP at follow-up as they were immediately after CE (1.78±0.37 years before). CE also positively affected clinical practices, in that prosthetists reported using the measures more often with clinical patients, and planned to use them with future patients. Overall, the proportion of prosthetists in this study that were routinely using standardized measures at follow-up (43.9%) was similar to the 26.0–47.9% reported by other health professionals.2,6,8 However, requirements for functional outcomes reporting recently implemented by the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services have likely increased use above these previously-reported levels in fields such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech pathology that are subject to these requirements.25 Functional outcomes reporting using standardized outcome measures is not yet required in O&P, but may be in the future.

Results also showed that prosthetists' perspectives of the benefits to outcome measures varied. Most routine outcome measure users endorsed nearly all of the benefits listed in our survey. Non-routine users largely endorsed only two – that outcome measures `help to justify clinical decisions to payors' and `contribute to a comprehensive evaluation.' This consensus among routine and non-routine users regarding use of measures for justification is also supported by the finding that prosthetists more often used the AMP than the TUG. Although administration of the TUG requires less time, the AMP may be used to support determination of patients' functional level and provision of appropriate prosthetic componentry to payors.26 That non-routine users believed outcome measures could `help perform a comprehensive patient evaluation,' yet chose not to apply them in practice, suggests that the benefit may not justify the effort required to implement their use in routine practice. This conclusion is partially supported by the finding that almost 20% of non-routine users reported outcome measures `require more effort than they are worth,' while, none of the routine users perceived effort as a barrier. Further, although both groups acknowledged outcome measures were difficult to integrate into daily routines, a larger proportion of non-routine users (45.9%) endorsed this barrier compared to routine users (20.7%). The perception of value, in light of the difficulties and burdens of measurement, appears to reflect a significant philosophical difference between routine and non-routine outcome measure users in this study.

Fundamental differences in attitudes towards outcomes measurement were also observed in the numbers of prosthetists in each group that endorsed other benefit statements. For example, nearly twice as many routine users as non-routine users (relative to the size of each subsample) agreed that outcome measures `provide useful information.' That one-third of the prosthetists in the study, including several routine users, elected not to endorse this statement is also interesting. One reason that so many prosthetists felt outcome measure information was not useful to clinical practice may be the relative lack of population-specific normative data (e.g., typical scores from large numbers of individuals grouped by age, sex, level, and/or etiology of amputation) for most measures suited to prosthetic patients, including the AMP and TUG.1 Normative data (or norms) are critical to interpreting scores obtained with a measure as they allow practitioners to more effectively compare each patient's score with similar individuals. A scarcity of norms has been suggested as a reason for therapists' tempered use of outcome measures.11 Prosthetists may also question the value of outcomes measurement, when it is not directly reimbursed under current prosthetic payment policies. Similarly, compensation has been cited as a barrier to therapists use of outcome measures.14

Overall, 1.4–2.8 times more routine users than non-routine users agreed with the benefit statements listed in the survey. These results suggest that positive attitudes or perceptions toward outcomes measurement might facilitate use of outcome measures in clinical practice. Conversely, negative attitudes or perceptions may inhibit use of measures. Such a finding is consistent with other investigators that reported health professionals' positive and negative attitudes toward outcomes measurement may be both a barrier and a facilitator, respectively, to use of outcome measures.2,6,9,11,14 Thus it would appear that strategies to educate and inform practitioners about the value of outcomes measurement, like CE provided in the prior study,5 may have the potential to positively and sustainably affect clinical practices. Similarly, efforts to address negative perceptions about measurement of clinical outcomes may help to eliminate or mitigate barriers to outcome measure use.

The barrier most commonly endorsed by both routine and non-routine users in this study was integration of outcome measures into clinical routines. As relatively few prosthetists endorsed other barriers, specific challenges to integration remain unclear. It may be that busy clinicians lack the time needed to effectively integrate outcomes measurement into their routines. Time is widely regarded as a principal barrier to outcome measure use by many health professionals.2,6–9 It is similarly perceived as a critical barrier to other professional behaviors, including implementing learning from CE27 and performing evidence-based practice.28 Thus, efforts to make outcomes measurement more efficient (e.g., use of brief instruments or computerized adaptive testing methods29) may help to facilitate integration. However, it is also acknowledged that barriers related to time can (and should) be addressed through changes in organizational culture, structure, and support.21 For example, clinic owners or administrators can help to develop and sustain an environment where outcomes measurement is valued by allowing practitioners time to use outcome measures with patients, providing clinicians and staff opportunities to attend outcome measure training, and using information obtained from outcome measures to guide business or personnel decisions. The extent to which such activities, in combination with CE, affect positive changes in prosthetists' use of outcome measures should be considered a priority for future study.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, this study included a small number of prosthetists, relative to the number of professionals in the field (i.e., there are about 3600 prosthetists in the U.S.30). Prosthetists in prior study5 may also have been motivated to learn about outcome measures. So, it is possible that our sample may not reflect the experiences or perceptions of prosthetists nationwide. Second, not everyone in the original study5 responded to our follow-up survey. It is possible that responses from non-respondents would have affected results. However, effects of non-response are believed to be negligible, as loss-to-follow-up was lower than the 20% attrition often considered to be an indicator of bias in longitudinal studies,31,32 and similar numbers of prosthetists originally classified as routine and non-routine users in the original study5 were lost to follow-up (i.e., 8 and 7, respectively). Further, no significant differences were found between prosthetists in the prior study and the subsample included here (i.e., there appears to be no systematic bias among those that completed each survey). Lastly, the CE provided in the prior study5 was focused on use of performance-based measures. Thus, the long-term effectiveness of CE reported here may not apply to other forms of outcome measures, like self-report. Additional work would be needed to assess if CE related to selection and use of self-report measures can facilitate their use in clinical practice.

Conclusion

Focused continuing education has a long-term effect on prosthetists' confidence using outcome measures with their clinical patients. Prosthetists generally agree that outcome measures offer benefits to professional practice. However, prosthetists also perceive numerous barriers to routine use of standardized outcome measures. As expected, benefits are perceived most by those that routinely use outcome measures, and barriers are most prevalent among those that do not. Overall, results of this study suggest that CE courses have the potential to change clinicians' practices related to implementation of outcomes measurement, but efforts to address remaining barriers are still needed.

Clinical Relevance.

Continuing education (CE) had a significant long-term impact on prosthetists' confidence administering outcome measures and influenced their clinical practices. Twenty percent of prosthetists, that previously were non-routine outcome measure users, became routine users after CE. There remains a need to develop strategies to integrate outcome measurement into routine clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

None

Funding/Support Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the U.S. National Institutes of Health under award number HD-065340. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

List of Abbreviations

- AMP

Amputee Mobility Predictor

- CE

continuing education

- O&P

orthotics and prosthetics

- SD

standard deviation

- TUG

Timed Up and Go

- U.S.

United States

Appendix 1 - Pre-Training Survey

- Please indicate your gender:

-

□Male

-

□Female

-

□

- Please indicate your ethnicity:

-

□Hispanic or Latino

-

□Not Hispanic or Latino

-

□

- Please indicate your race: (please check all that apply)

-

□White

-

□Black or African-American

-

□American Indian or Alaskan Native

-

□Asian

-

□Native

-

□Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander

-

□

- What type of prosthetics certificate and/or degree do you possess? (Please choose all that apply)

-

□Certificate

-

□Bachelors (e.g., BPO)

-

□Masters (e.g., MSPO/MPO)

-

□Doctorate (e.g., PhD)

-

□Other: _____________________________

-

□

- Please indicate your clinical certification? (Please choose one)

-

□CP

-

□CPO

-

□Other: _____________________________

-

□

- Do you have work experience in areas of rehabilitation other than prosthetics? (Please choose all that apply)

-

□Physical therapy / physiotherapy

-

□Occupational therapy

-

□Nursing

-

□Physical therapy assistant

-

□Exercise physiology

-

□Physical training

-

□Other: _____________________________

-

□

- How long have you been in clinical practice:

- _______ years

-

Have you ever administered any of the following standardized outcome measures in your daily clinical practice? (Check all that apply)

Outcome measure Never Rarely Sometimes Often Always

Activities specific balance confidence scale (ABC) □ □ □ □ □

Amputee mobility predictor (AMP) □ □ □ □ □

Berg Balance Scale (BBS) □ □ □ □ □

Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) □ □ □ □ □

Distance Walk Test (e.g., 10-meter walk test) □ □ □ □ □

Functional Mobility of the Amputee (FMA) □ □ □ □ □

Timed Walk Test (TWT) (e.g., 2 minute walk test) □ □ □ □ □

Houghton Questionnaire □ □ □ □ □

Locomotor Capabilities Index (LCI) □ □ □ □ □

Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS) □ □ □ □ □

Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) □ □ □ □ □

Orthotic and Prosthetic Users Survey (OPUS) □ □ □ □ □

Patient Assessment Validation Evaluation Test (PAVET) □ □ □ □ □

Prosthetic Profile of the Amputee (PPA) □ □ □ □ □

Prosthesis Evaluation Questionnaire (PEQ) □ □ □ □ □

Short-Form 8, 12, or 36 (SF-8, SF-12, or SF-36) □ □ □ □ □

Rivermead Mobility Index (RMI) □ □ □ □ □

Step Activity Monitor (SAM) (e.g., Stepwatch or Galileo) □ □ □ □ □

Trinity Amputation and Prostheses Experience Scales (TAPES) □ □ □ □ □

Timed Up and Go (TUG) □ □ □ □ □

Please indicate names of any other standardized outcome measures you may use in your routine clinical practice:

-

Please indicate how frequently you currently use standardized outcome measures (like those listed above) for the stated purpose:

Purpose Never Rarely Sometimes Often Always

Document patient status □ □ □ □ □

Inform clinical decisions □ □ □ □ □

Justify selection of interventions □ □ □ □ □

Monitor patients over time □ □ □ □ □

Communicate information to others □ □ □ □ □

Predict patient outcomes □ □ □ □ □

-

How confident are you in your current ability to administer the:

Outcome measure Not at all A little bit Somewhat Quite a bit Very much

Time up and go (TUG) □ □ □ □ □

Amputee mobility predictor (AMP) □ □ □ □ □

Appendix 2 - Post-Training Survey

-

How confident are you in your current ability to administer the:

Outcome measure Not at all A little bit Somewhat Quite a bit Very much

Time up and go (TUG) □ □ □ □ □

Amputee mobility predictor (AMP) □ □ □ □ □

-

Please estimate the time it currently takes you to administer the following tests:

Outcome measure Minutes Seconds

Time up and go (TUG)

Amputee mobility predictor (AMP)

Appendix 3 - Follow-up Survey

-

1

How confident are you in your current ability to administer the:

Outcome measure Not at all A little bit Somewhat Quite a bit Very much

Time up and go (TUG) □ □ □ □ □

Amputee mobility predictor (AMP) □ □ □ □ □

-

2

Please estimate the time it currently takes you to administer the following tests:

Outcome measure Minutes Seconds

Time up and go (TUG)

Amputee mobility predictor (AMP)

-

3

How often did you use the following outcome measures with your patients, since participating in the outcomes measurement course:

Outcome measure Never Rarely Sometimes Often Always

Time up and go (TUG) □ □ □ □ □

Amputee mobility predictor (AMP) □ □ □ □ □

Another standardized outcome measure □ □ □ □ □

-

4

In the future, how often will you administer the:

Outcome measure Never Rarely Sometimes Often Always

Time up and go (TUG) □ □ □ □ □

Amputee mobility predictor (AMP) □ □ □ □ □

-

5

In your opinion, how much do outcome measures:

Not at all A little bit Somewhat Quite a bit Very much

Facilitate communication with patients □ □ □ □ □

Facilitate communication among medical professionals □ □ □ □ □

Contribute to a comprehensive evaluation □ □ □ □ □

Contribute to an efficient evaluation □ □ □ □ □

Contribute to better patient outcomes □ □ □ □ □

Contribute to marketing efforts □ □ □ □ □

Help guide clinical decisions □ □ □ □ □

Help motivate patients □ □ □ □ □

Help justify clinical decisions to payors □ □ □ □ □

Provide useful information □ □ □ □ □

-

6

In your opinion, how much of a problem are outcome measures because they:

Not at all A little bit Somewhat Quite a bit Very much

Add a burden to patients □ □ □ □ □

Are difficult to select □ □ □ □ □

Are difficult to set up □ □ □ □ □

Are difficult to administer □ □ □ □ □

Are difficult to interpret □ □ □ □ □

Require special knowledge □ □ □ □ □

Require special training □ □ □ □ □

Require special equipment □ □ □ □ □

Require more effort than they are worth □ □ □ □ □

Are difficult to integrate into your routine □ □ □ □ □

Are beyond your scope of practice □ □ □ □ □

Interfere with your autonomy as a provider □ □ □ □ □

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Brian Hafner, Sara Morgan, Ignacio Gaunaurd, Robert Gailey

Acquisition of data: Sara Morgan, Igaacio Gaunaurd, Susan Spaulding

Analysis and interpretation of data: Rana Salem, Susan Spaulding, Brian Hafner

Drafting of manuscript: Susan Spaulding, Brian Hafner

Critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content: Sara Morgan, Ignacio Gaunaurd, Robert Gailey, Rana Salem

Obtained funding: Brian Hafner

Declaration of Conflicting Interest The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Heinemann AW, Connelly L, Ehrlich-Jones L, Fatone S. Outcome instruments for prosthetics: clinical applications. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014;25(1):179–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jette DU, Halbert J, Iverson C, Miceli E, Shah P. Use of standardized outcome measures in physical therapist practice: perceptions and applications. Phys Ther. 2009;89(2):125–35. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wedge FM, Braswell-Christy J, Brown CJ, Foley KT, Graham C, Shaw S. Factors influencing the use of outcome measures in physical therapy practice. Physiother Theory Pract. 2012;28(2):119–33. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2011.578706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunckley M, Aspinal F, Addington-Hall JM, Hughes R, Higginson IJ. A research study to identify facilitators and barriers to outcome measure implementation. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2005;11(5):218–25. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2005.11.5.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaunaurd I, Spaulding SE, Amtmann D, Salem R, Gailey R, Morgan SJ, Hafner BJ. Use of and confidence in administering outcome measures among clinical prosthetists: Results from a national survey and mixed-methods training program. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2015;39(4):314–21. doi: 10.1177/0309364614532865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatfield DR, Ogles BM. The use of outcome measures by psychologists in clinical practice. Professional Psychology-Research and Practice. 2004;35(5):485–91. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stapleton T, McBrearty C. Use of Standardised Assessments and Outcome Measures among a Sample of Irish Occupational Therapists working with Adults with Physical Disabilities. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2009;72(2):55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valier AR, Jennings AL, Parsons JT, Vela LI. Benefits of and barriers to using patient-rated outcome measures in athletic training. J Athl Train. 2014;49(5):674–83. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrams D, Davidson M, Harrick J, Harcourt P, Zylinski M, Clancy J. Monitoring the change: current trends in outcome measure usage in physiotherapy. Man Ther. 2006;11(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stokes EK, O'Neill D. Use of Outcome Measures in Physiotherapy Practice in Ireland from 1998 to 2003 and Comparison to Canadian Trends. Physiotherapy Canada. 2008;60(2):109–16. doi: 10.3138/physio.60.2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swinkels RA, van Peppen RP, Wittink H, Custers JW, Beurskens AJ. Current use and barriers and facilitators for implementation of standardised measures in physical therapy in the Netherlands. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowman J. Challenges to Measuring Outcomes in Occupational Therapy: a Qualitative Focus Group Study. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2006;69(10):464–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skeat J, Perry A. Exploring the implementation and use of outcome measurement in practice: a qualitative study. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2008;43(2):110–25. doi: 10.1080/13682820701449984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Peppen RPS, Maissan FJF, Van Genderen FR, Van Dolder R, Van Meeteren NLU. Outcome measures in physiotherapy management of patients with stroke: a survey into self-reported use, and barriers to and facilitators for use. Physiotherapy Research International. 2008;13(4):255–70. doi: 10.1002/pri.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marinopoulos SS, Dorman T, Ratanawongsa N, Wilson LM, Ashar BH, Magaziner JL, Miller RG, Thomas PA, Prokopowicz GP, Qayyum R, Bass EB. Effectiveness of continuing medical education. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2007;(149):1–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis D, O'Brien MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? Jama. 1999;282(9):867–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis D. Does CME work? An analysis of the effect of educational activities on physician performance or health care outcomes. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1998;28(1):21–39. doi: 10.2190/UA3R-JX9W-MHR5-RC81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harding KE, Stephens D, Taylor NF, Chu E, Wilby A. Development and evaluation of an allied health research training scheme. J Allied Health. 2010;39(4):e143–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antunes B, Harding R, Higginson IJ. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in palliative care clinical practice: a systematic review of facilitators and barriers. Palliat Med. 2014;28(2):158–75. doi: 10.1177/0269216313491619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyce MB, Browne JP, Greenhalgh J. The experiences of professionals with using information from patient-reported outcome measures to improve the quality of healthcare: a systematic review of qualitative research. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2014 doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duncan EA, Murray J. The barriers and facilitators to routine outcome measurement by allied health professionals in practice: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:96. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):142–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gailey RS, Roach KE, Applegate EB, Cho B, Cunniffe B, Licht S, Maguire M, Nash MS. The amputee mobility predictor: an instrument to assess determinants of the lower-limb amputee's ability to ambulate. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(5):613–27. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.32309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bordage G. Continuing Medical Education Effect on Physician Knowledge: Effectiveness of Continuing Medical Education: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Educational Guidelines. CHEST Journal. 2009;135(3_suppl):29S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Potter K, Cohen ET, Allen DD, Bennett SE, Brandfass KG, Widener GL, Yorke AM. Outcome measures for individuals with multiple sclerosis: recommendations from the American Physical Therapy Association Neurology Section task force. Phys Ther. 2014;94(5):593–608. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laferrier JZ, Gailey R. Advances in lower-limb prosthetic technology. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2010;21(1):87–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price DW, Miller EK, Rahm AK, Brace NE, Larson RS. Assessment of barriers to changing practice as CME outcomes. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2010;30(4):237–45. doi: 10.1002/chp.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harding KE, Porter J, Horne-Thompson A, Donley E, Taylor NF. Not Enough Time or a Low Priority? Barriers to Evidence-Based Practice for Allied Health Clinicians: Barriers to Evidence-Based Practice. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2014;34(4):224–31. doi: 10.1002/chp.21255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cella D, Gershon R, Lai JS, Choi S. The future of outcomes measurement: item banking, tailored short-forms, and computerized adaptive assessment. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(Suppl 1):133–41. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DaVanzo JE, El-Gamil A, Heath S, Pal S, Li J, Luu PH, Dobson A. Projecting the Adequacy of Workforce Supply to Meet Patient Demand: Analysis of the Orthotics and Prosthetics (O&P) Profession. Dobson DaVanzo & Associates, LLC; Vienna, VA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dumville JC, Torgerson DJ, Hewitt CE. Reporting attrition in randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2006;332(7547):969–71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7547.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fewtrell MS, Kennedy K, Singhal A, Martin RM, Ness A, Hadders-Algra M, Koletzko B, Lucas A. How much loss to follow-up is acceptable in long-term randomised trials and prospective studies? Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(6):458–61. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.127316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]