Abstract

Purpose

Little prospective data is available on clinical outcomes and immune correlates from combination radiation and immunotherapy. We conducted a phase I trial (NCT02239900) testing stereotactic ablative radiation therapy (SABR) with ipilimumab.

Experimental Design

SABR was given either concurrently (1 day after the first dose) or sequentially (1 week after the second dose) with ipilimumab (3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for 4 doses) to 5 treatment groups: concurrent 50 Gy (in 4 fractions) to liver; sequential 50 Gy (in 4 fractions) to liver; concurrent 50 Gy (in 4 fractions) to lung; sequential 50 Gy (in 4 fractions) to lung; and sequential 60 Gy (in 10 fractions) to lung or liver. Maximum tolerated dose was determined with a 3+3 dose de-escalation design. Immune marker expression was assessed by flow cytometry.

Results

Among 35 patients who initiated ipilimumab, 2 experienced dose-limiting toxicity and 12 (34%) grade 3 toxicity. Response outside the radiation field was assessable in 31 patients. Three patients (10%) exhibited partial response and 7 (23%) experienced clinical benefit (defined as partial response or stable disease lasting ≥6 months). Clinical benefit was associated with increases in peripheral CD8+ T-cells; CD8+/CD4+ T-cell ratio; and proportion of CD8+ T-cells expressing 4-1BB and PD1. Liver (vs. lung) irradiation produced greater T-cell activation, reflected as increases in the proportions of peripheral T-cells expressing ICOS, GITR, and 4-1BB.

Conclusions

Combining SABR and ipilimumab was safe with signs of efficacy; peripheral T-cell markers may predict clinical benefit; and systemic immune activation was greater after liver irradiation.

Keywords: Stereotactic ablative radiation therapy, immunotherapy, ipilimumab, trial correlates

Introduction

Emerging data show promise for combining radiation with checkpoint inhibitors such as the CTLA-4 inhibitor ipilimumab.(1, 2) The rationale is that radiation produces immunogenic cell death and upregulates surface MHC molecules, which promote tumor-directed immune stimulation and T-cell receptor diversity.(3, 4) Checkpoint inhibitors have been hypothesized to augment radiation-induced antigen production by synergistically priming and sustaining the immune system.(1) By combining these two agents, radiation may work to turn individual tumors into potent tumor-specific “vaccines” and potentially produce tumor shrinkage outside the radiation field. This phenomenon of a clinical response in an un-irradiated site is known as the abscopal effect.(1, 5, 6)

Despite growing preclinical support for such combinations,(3, 5, 7, 8) clinical data are limited. Reported clinical studies have utilized a range of radiation doses, target sites, and sequencing of radiation and immunotherapy.(9–11) To the best of our knowledge, no clinical studies have addressed differences associated with such variations, although animal studies have suggested that high, ablative doses are more effective.(8, 12) With regard to optimal doses for thoracic irradiation, stereotactic ablative radiation (SABR) regimens that achieve biologically effective doses (BED) of approximately 100 Gy (as utilized here) may produce more immunogenic cell death.(13) However, SABR is more toxic than conventional radiation, raising concerns about its safety in combination with immunotherapy.(14, 15) We present a phase I trial investigating 5 parallel treatment groups testing 2 sequencing regimens (concurrent vs. sequential) and 2 radiation target organs (lung vs. liver).

Patients and Methods

Patients

Major inclusion criteria were metastatic solid tumor refractory to standard therapies and ≥1 lesion in the liver or lung amenable to SABR with ≥1 additional non-contiguous lesion for monitoring. This study was approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study design

This open-label study had a modified “3+3” dose de-escalation design. All patients were to receive the FDA-approved dose of ipilimumab (3 mg/kg) every 3 weeks for 4 doses. SABR was administered to either a lung or liver lesion to 50 Gy in 4 fractions. However, if an unacceptably high dose were administered to normal organs utilizing 50 Gy in 4 fractions, patients were enrolled in the fifth treatment arm, in which 60 Gy was given in 10 fractions to either a liver or lung lesion. If ≥2 dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) were observed among 6 patients, then the subsequent 6 patients were treated with a reduced radiation dose. Dose de-escalation was conducted independently in the 5 treatment groups.

Sequencing of ipilimumab and radiation was either concurrent (with radiation begun the day after the first dose of ipilimumab) or sequential (with radiation initiated the week after the second dose of ipilimumab). Patients were treated in 5 parallel non-randomized groups as follows: Group 1, concurrent radiation to 50 Gy in 4 fractions to a liver lesion; Group 2, sequential radiation to 50 Gy in 4 fractions to a liver lesion; Group 3, concurrent radiation to 50 Gy in 4 fractions to a lung lesion; Group 4, sequential radiation to 50 Gy in 4 fractions to a lung lesion; and Group 5, sequential radiation to a liver or a lung lesion to 60 Gy in 10 fractions. Major criteria for DLTs were grade ≥3 non-hematologic/laboratory toxicity or grade ≥4 hematologic/laboratory toxicity related to the combination of ipilimumab and radiation with severity assessed via Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0.

Response assessment

Response was evaluated in terms of immune-related response criteria (ir-RC)(16) as follows: global response (response of both the irradiated lesion and lesions outside the radiation field); in-field response (response of protocol-irradiated lesions), and out-of-field response (response of lesions outside the radiation field). Because our goal was to evaluate the abscopal effects, the primary response metric was out-of-field response. Clinical benefit was defined as ir-RC stable disease (irSD) lasting ≥6 months, complete response (irCR), or partial response (irPR), for which only out-of-field lesions were assessed.

Peripheral immune correlates

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were analyzed through the MD Anderson Immunotherapy Platform program. Blood samples were drawn for correlative analysis before the first dose of ipilimumab, after SABR but before the next dose of ipilimumab (mid IPI), and approximately 3 weeks after the last dose of ipilimumab (post IPI). Following whole blood collection, PBMCs were separated utilizing a Ficoll gradient at room temperature.(17) After appropriate forward/side scatter and live cell selection, three peripheral T-cell populations were identified by flow cytometry: total CD8+ (CD3+CD8+), CD4+ T effector cells (Teffs) (CD3+CD4+FOXP3−), and CD4+ T regulatory cells (Treg) (CD3+CD4+FOXP3+CD127−/lo). Absolute lymphocyte counts, obtained at the same time were combined with cell proportions from flow cytometry to calculate absolute counts for each T-cell population. These absolute counts were expressed as a “fold” difference relative to that patient’s baseline measurement ([cell count mid or post ipilimumab] / [cell count at baseline]). Notably, when the sample was drawn after SABR, those patients had already received either their first (in the concurrent groups) or second (in the sequential groups) dose of ipilimumab. The following immune markers were stained and quantified by flow: 4-1BB, OX40, LAG3, ICOS, GITR, CTLA4, TIM-3, and PD1. Immune marker expression was expressed as a percentage of expressing cells within each cell population.

Statistical analysis

Differences in PBMCs were assessed with the exact Wilcoxon rank-sum and signed-rank tests. PBMC marker analyses were considered exploratory, and results must be interpreted cautiously. All P values were 2-sided. The Kaplan-Meier product limit method was used to estimate overall and progression-free survival distributions. Statistical analyses were done with SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patients

Thirty-five patients were enrolled from September 8, 2014 to August 7, 2015. All patients received ≥1 cycles of ipilimumab, and 26 patients (74%) completed all 4 cycles. SABR was initiated in 32 patients (91%); 31 (89%) completed the prescribed SABR and provided ≥1 set of follow-up images, thus making them evaluable for disease response. All 4 patients who did not complete SABR were taken off protocol due to rapid disease progression. When this manuscript was written, 30 patients (86%) had been removed from the study, 27 for disease progression, 2 for toxicity, and 1 for death unrelated to treatment. Median follow-up time was 9.3 months (range 8.1–11.6 months) for the 5 patients who remained on study.

The median age for all patients was 60 years (range 34–82); 18 (51%) were men and 17 (49%) women (Table 1). The most common treated histologies were non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC; n=8), followed by colorectal carcinoma (CRC; n=4), sarcoma (n=3), and renal cell carcinoma (RCC; n=3). Thirty-one patients (89%) had received prior systemic therapy (median 2 prior systemic therapies, range 0–9) and 22 (63%) had received prior radiation for metastatic disease (Table 1). Two patients had received prior immunotherapy, one a dendritic cell vaccine and the other a CTLA-4 inhibitor followed by interferon-alpha.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and treatment characteristics

| Characteristics | All Patients (n=35) |

Group 1: Liver 50/4* Concurrent (n=7) |

Group 2: Liver 50/4 Sequential (n=8) |

Group 3: Lung 50/4 Concurrent (n=6) |

Group 4: Lung 50/4 Sequential (n=8) |

Group 5: Liver/Lung 60/10 Sequential (n=6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 18 (51%) | 3 (43%) | 5 (63%) | 1 (17%) | 4 (50%) | 5 (83%) |

| Female | 17 (49%) | 4 (57%) | 3 (37%) | 5 (83%) | 4 (50%) | 1 (17%) |

| Median age (range) | 60 (34–82) | 53 (39–66) | 62 (34–74) | 54 (48–62) | 64 (45–82) | 62 (51–80) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 30 (86%) | 5 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 6 |

| Asian | 3 (8%) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| African American |

2 (6%) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Primary histology | ||||||

| NSCLC 8 | Unknown primary 2 | Cervical 1 | Adrenocortical 1 | Adrenocortical 1 | Gastroesophageal 1 | |

| Colorectal 4 | Cholangiocarcinoma 1 | Colorectal 1 | Colorectal 1 | Colorectal 2 | NSCLC 3 | |

| Sarcoma 3 | Squamous HNC 1 | Gastric 1 | Salivary 1 | NSCLC 1 | Prostate 1 | |

| RCC 3 | NSCLC 1 | NSCLC 3 | Sarcoma 1 | Pancreatic 1 | RCC1 | |

| Other 17 | RCC 2 | Neuroendocrine 2 | Anaplastic Thyroid 1 | Sarcoma 2 | ||

| Uveal Melanoma 1 | Papillary Thyroid 1 | |||||

| Prior anticancer therapy after metastasis diagnosis | ||||||

| Radiation | 22 (63%) | 4 (47%) | 7 (88%) | 2 (33%) | 5 (63%) | 4 (67%) |

| Immune | 2 (6%) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Systemic | 31 (89%) | 6 (89%) | 8 (100%) | 4 (67%) | 7 (88%) | 6 (100%) |

| Median number systemic therapies |

2 (0–9) | 3 (0–7) | 3 (1–7) | 1 (0–2) | 2 (0–9) | 3 (2–7) |

Indicates the dose (in Gy) and number of fractions.

Abbreviations: NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; HNC, head and neck cancer

Safety

Two DLTs were observed: a patient in Group 1 (concurrent 50 Gy/4 fractions to liver) experienced grade 3 pancreatitis and lipase elevation and a patient in Group 2 (sequential 50/4 fractions to liver) experienced grade 3 increase in bilirubin and aspartate aminotransferase. Grade 3+ toxicity attributable to either radiation or immunotherapy is shown in Table 2. No patient experienced grade 4 or 5 treatment-related toxicity. Among all patients, 12 (34%) exhibited a grade 3 toxicity, the most frequent being colitis (in 4 patients [11%]). Most episodes of toxicity were self-limiting and could be managed as an outpatient. Only 2 patients were taken off protocol because of toxicity. One of those patients had received concurrent ipilimumab and lung SABR and experienced intussusception necessitating small bowel resection; pathology examination revealed tumor at the intussusception site with no evidence of inflammation. This toxicity was considered as grade 4 small intestinal obstruction unrelated to study therapy. The second patient was removed from study for elevations in liver enzymes meeting the criteria for grade 3 laboratory abnormalities after receiving ipilimumab and liver SABR. No patient experienced grade >1 pneumonitis.

Table 2.

Grade 3 toxicity probably or definitely related to radiation or immunotherapy

| Characteristics | All Patients (n=35) |

Group 1: Liver 50/4* Concurrent (n=7) |

Group 2: Liver 50/4 Sequential (n=8) |

Group 3: Lung 50/4 Concurrent (n=6) |

Group 4: Lung 50/4 Sequential (n=8) |

Group 5: Liver/Lung 60/10 Sequential (n=6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade 3** | 12 (34%) | 2 (29%) | 4 (50%) | 2 (33%) | 2 (25%) | 2 (33%) |

| Dose-limiting toxicities | 2 (6%) | 1 (14%) | 1 (13%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Specific toxicities | ||||||

| ALT/AST elevation | 2 (6%) | 1 (14%) | 1 (13%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bilirubin elevation | 1 (3%) | 1 (14%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cholecystitis | 1 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (13%) | 0 |

| Colitis | 4 (11%) | 0 | 2 (25%) | 0 | 1 (13%) | 1 (17%) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (6%) | 0 | 1 (13%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) |

| Fatigue | 1 (3%) | 0 | 1 (13%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fever | 1 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) |

| Pain | 1 (3%) | 0 | 1 (13%) | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 |

| Pancreatitis/lipase elevation | 1(3%) | 1 (14%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pituitary hypophysitis | 1 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) |

| Rash maculopapular | 3 (9%) | 0 | 2 (25%) | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 |

| Upper muscle weakness | 1 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 |

Indicates the dose (in Gy) and number of fractions.

No grade 4 or 5 toxicities probably or definitely related to treatment were observed.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

Patient outcomes

Among all patients, the median progression-free and overall survival times were 3.2 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.73–4.38) and 10.2 months (95% CI 5.60–not calculable). One patient died after the second ipilimumab dose, and had received 2 of the 4 planned fractions of lung SABR. Although the exact cause of death was unclear, this patient had significant metastatic disease burden and recent ST-elevation myocardial infarctions deemed unrelated to protocol therapy. This patient did not experience any DLTs or any ongoing treatment-related toxicity at the time of death.

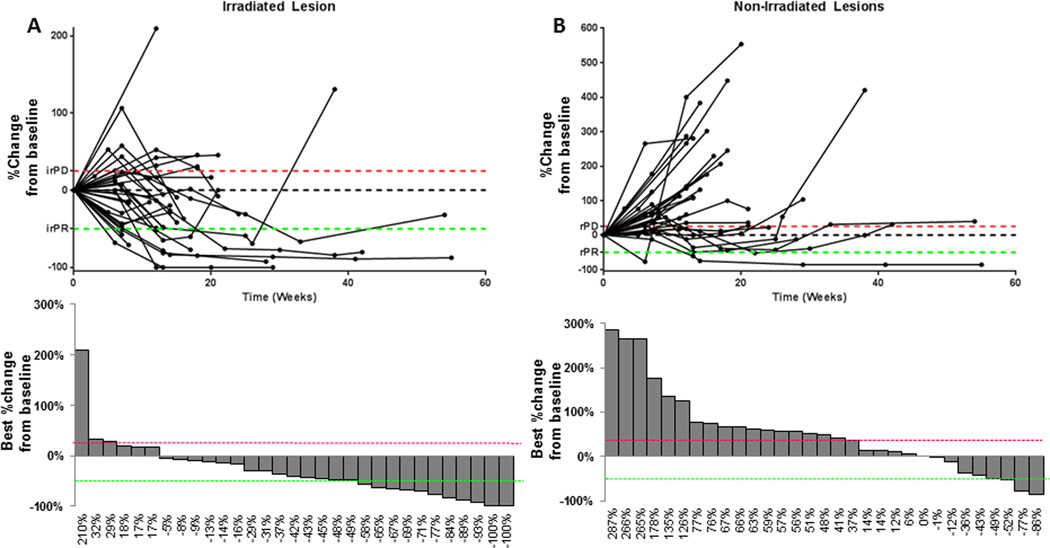

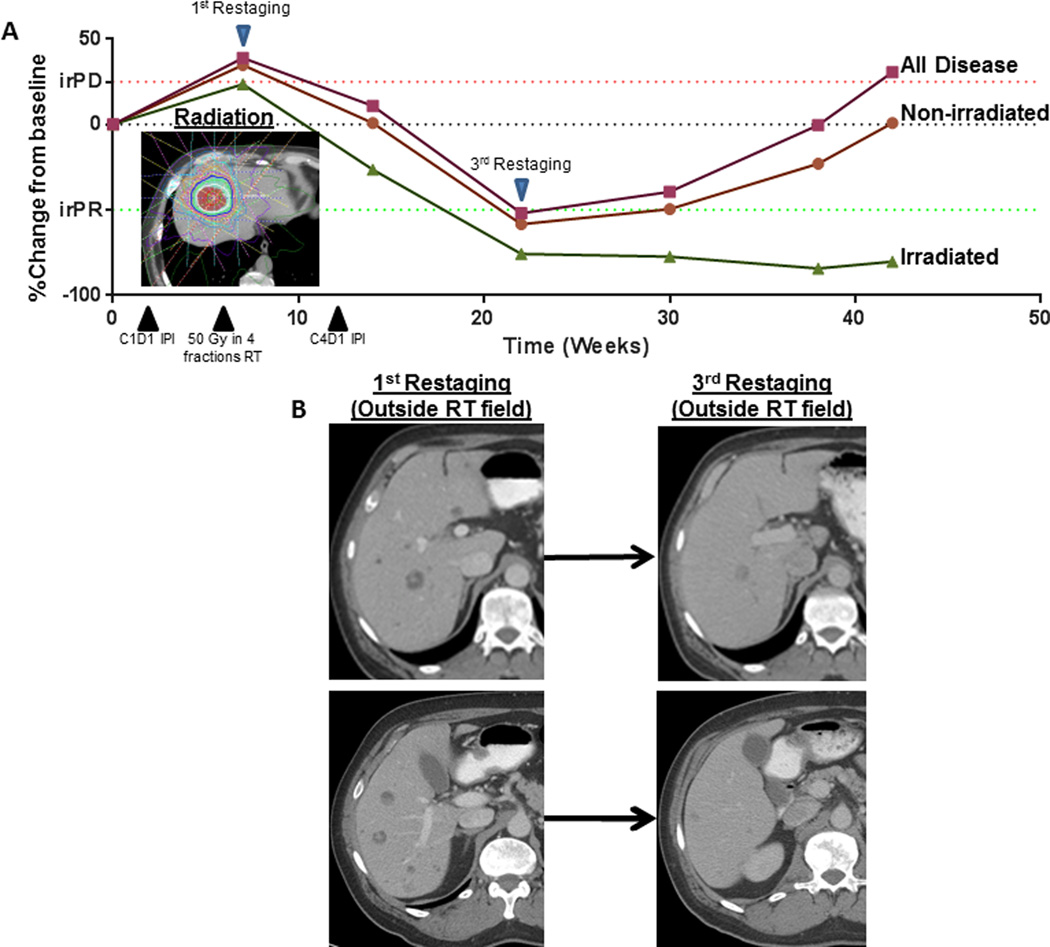

Because our primary response metric was out-of-field disease, we limited our response assessment to the 31 patients with imaging after baseline. Three patients (10%) had an irPR, 10 patients (32%) had irSD, and 18 patients had irPD (Fig. 1). Clinical benefit, defined as out-of-field irPR or irSD lasting at least 6 months, was achieved in 7 patients (23%), 1 in group 1 (adenocarcinoma unknown primary), 2 in Group 2 (neuroendocrine unknown primary and gastric adenocarcinoma), 2 in Group 3 (salivary gland adenocarcinoma and anaplastic thyroid cancer), 1 in Group 4 (adrenocortical carcinoma), and 1 in Group 5 (non-small cell lung cancer). Treatment response for representative patient with a neuroendocrine tumor in group 2 is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Disease response on protocol. Disease response over time (spider plots) and best achieved disease response (waterfall plots) for irradiated lesions (A) and for lesions outside the radiation field (B). For reference, the immune-related response criteria (ir-RC) cutpoints for partial response (irPR) are shown in green and for progressive disease (irPD) are shown in red.

Figure 2.

(A) Disease response over time for a patient with neuroendocrine tumor who received sequential radiation and ipilimumab to a liver lesion; solid green line indicates the irradiated lesion, solid orange line, non-irradiated (out-of-field) disease; and solid red line, all disease. Dotted lines indicate immune-related response criteria cutpoints for partial response (irPR) (red) and progressive disease (irPD) (green). (B) Representative CT scans with contrast show hepatic lesions outside the radiation field at first and the third restaging assessment. Abbreviations: C1D1, cycle 1 day 1, C4D1, cycle 4 day 1, and IPI, ipilimumab.

Changes in peripheral T-cell population counts

PBMC correlates from at least 1 time point were available for 22 patients; 12 had both baseline and post-SABR measurements and 15 had both baseline and post-ipilimumab measurements. Representative flow cytometry plots and gating is presented in Figure 3a. After SABR, patients who achieved clinical benefit compared to those who did not exhibited increases in the CD8+ count (median fold change: 1.22 vs. 0.82, P=0.07) and CD8+/CD4+ ratio (1.31 vs. 0.76, P=0.02). Similarly after ipilimumab patients who achieved clinical benefit exhibited higher increases in CD8+ count (1.20 vs. 0.89, P=0.004) and CD8+/CD4+ ratio (1.24 vs. 0.84, P=0.009) (Fig. 3b). When stratified by clinical benefit, no significant changes were noted in total CD4+ count and in the Treg and Teff cell subtypes (all P>0.05) (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Association of peripheral blood mononuclear populations with clinical benefit. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing cell gating for immune correlate analysis of lymphocyte subpopulations. A schematic is shown of blood draw timing in relationship to ipilimumab and radiation administration. (B) Changes in peripheral blood mononuclear cell populations from baseline to after the first 1–2 cycles of ipilimumab and radiation therapy (mid IPI) and after the last dose of ipilimumab (post IPI), stratified by clinical benefit (defined as immune-related Response Criteria rating of stable disease [irSD] lasting ≥6 months, complete response [irCR], or partial response [irPR] of out-of-field lesions). Significant differences were seen between patients with or without clinical benefit in CD8+ T-cells after ipilumumab (post-IPI; P=0.004) and in CD8+/CD4+ ratio after radiation (post-RT; P=0.02) and after ipilimumab (post-IPI; P=0.009). Abbreviations: C1D1, cycle 1 day 1, C2D1, cycle 2 day 1, C3D1, cycle 3 day 1, C4D1, cycle 4 day 1, RT, radiation, and IPI, ipilimumab.

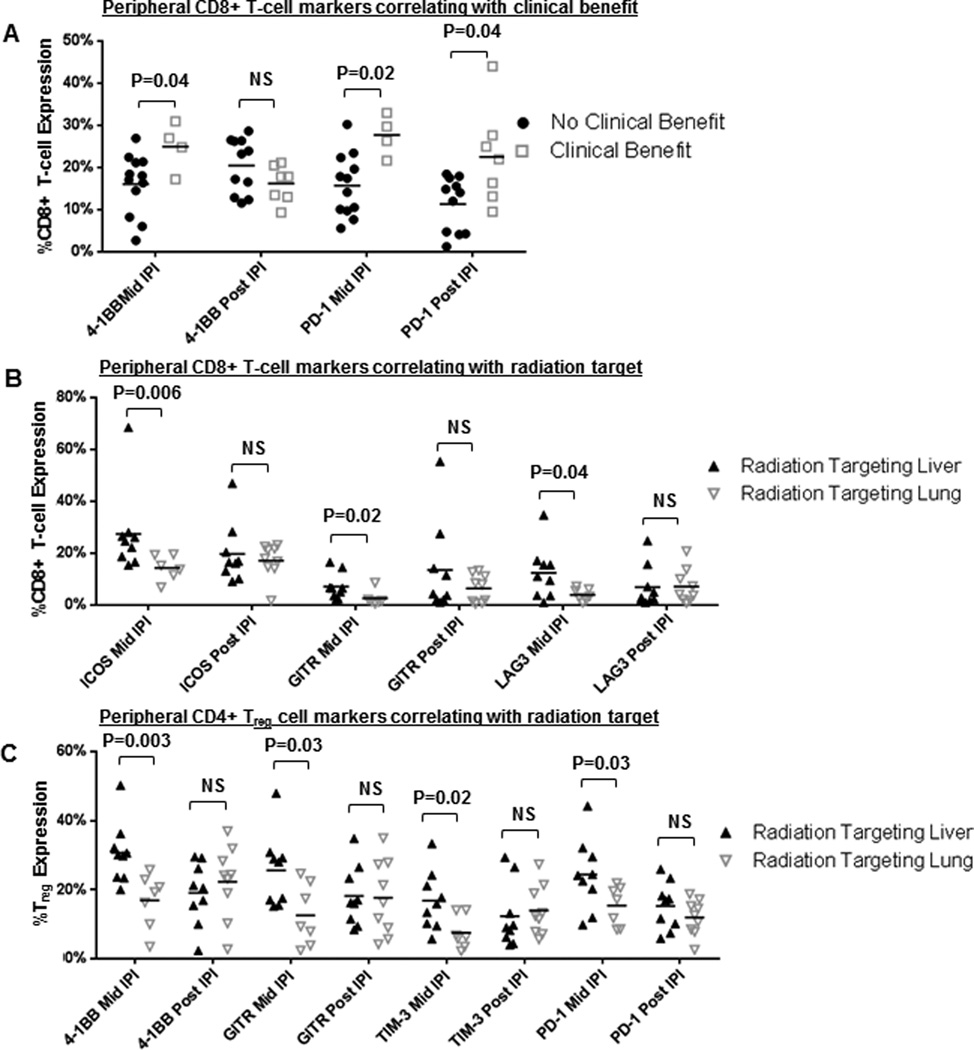

Changes in the activation profile of peripheral T-cell populations

Compared with patients who did not achieve clinical benefit, those who did had increased proportions of CD8+ cells expressing 4-1BB (median 26% vs 18%, P=0.04) and PD1 (median 28% vs 16%, P=0.02) after SABR (Fig. 4a). The higher proportion of CD8+ cells expressing PD1 in patients with clinical benefit after SABR persisted after ipilimumab (median 22% vs 14%, P=0.04) (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell surface marker expression and association with radiation target and clinical benefit. Changes in expression of immune-activating and -inhibitory markers from baseline until after the first 1–2 cycles of ipilimumab and radiation therapy (mid IPI) and from after the last dose of ipilimumab (post IPI) in peripheral CD8+ T-cells stratified by clinical benefit (A), in peripheral CD8+ T-cells stratified by radiation target (B), and in CD4+ Treg cells stratified by radiation target (C). Values are expressed as percentage of peripheral CD4+ Treg or CD8+ T-cells with marker expression. Abbreviations: N.S., not significant.

Differences in immune marker expression were also evident according to the irradiated organ (Fig. 4b). Compared with patients receiving lung radiation, patients receiving hepatic radiation had higher proportions of CD8+ cells expressing ICOS (median 25% vs. 15%), GITR (6.5% vs. 1.6%), and LAG3 (3.3% vs. 1.1%) (all P<0.05). Differences were also noted in Treg surface marker expression: hepatic (vs. lung) radiation was associated with increased proportions of Treg expressing the activating markers 4-1BB (median 30% vs. 19%), GITR (median 28% vs 9%), TIM-3 (median 16% vs 6%), and PD1 (median 24% vs. 17%) (all P<0.05). Significant differences associated with organ site target appeared transient and were only evident after radiation but not in the post ipilimumab time period (all P>0.05; Fig. 4b). No significant differences in PBMC population or surface marker expression were evident with radiation sequencing (concurrent vs. sequential). Full surface-marker profiles among CD8+ T-cells, Treg, and Teff are provided as Supplementary Figures S1–S3.

Ipilimumab and radiation reinduction

Protocol procedures allowed patients to receive an additional 4 cycles of 3 mg/kg ipilimumab and SABR if at least an irSD was achieved and >8 weeks had elapsed since the last dose of ipilimumab. Four patients received reinduction. Two patients achieved irSD, with best out-of-field responses of −15% and −16% from repeat-therapy baseline. The other 2 patients were found to have irPD and were thus removed from the study. Reinduction was well tolerated, with 1 episode of grade 2 hypophysitis.

Discussion

In this phase I trial, treatments combining liver or lung SABR at 50 Gy in 4 fractions or 60 Gy in 10 fractions concurrently or sequentially with ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg for 4 doses were considered safe. Two patients (6%) had DLTs, and even though rates of grade 3 treatment-related toxicity were non-negligible at 34%, most were self-limiting and managed as an outpatient. Data on efficacy is encouraging, with 10% out-of-field irPR and 23% clinical benefit. Analysis of PBMCs identified significant increases in peripheral CD8+ T-cells and CD8+/CD4+ ratio after the first 1–2 doses of ipilimumab and radiation among patients who achieved clinical benefit. Finally, achievement of clinical benefit and receipt of hepatic (vs. lung) irradiation were associated with transient increases in markers suggestive of increased peripheral T-cell activation.

Most prior trials investigating combination radiation therapy with checkpoint inhibitors used moderate hypofractionation (6–8 Gy/fraction in 1–3 fractions).(3, 10, 11) Yet many basic science reports have shown that higher, more ablative doses (12–30 Gy per fraction) are necessary to induce systemic immune effects.(7, 8, 12) With regard to thoracic SABR, radiation doses of approximately 100 Gy BED are considered ablative doses and produce different and possibly more immunogenic forms of cell death than conventional fractionation.(13, 18) Of the two doses used in this study, the BED for 50 Gy in 4 fractions was 112.5 Gy10, and the BED for 60 Gy in 10 fractions was 96 Gy10 (assuming α/β=10 for lung tumor as utilized in other reports(14, 19)). Use of high-BED radiation may also lead to increased toxicity.(14, 15) In this study the DLT incidence was not unacceptably high, indicating therapy safety. However, the frequency of grade 3 treatment-related toxicity was not insubstantial (34%). Reported rates of grade 3+ toxicity for ipilimumab monotherapy at 3 mg/kg for melanoma have ranged from 10% to 28%.(20–22) In CA184-043, the largest trial conducted to date combining radiation and immunotherapy, 26% of patients experienced grade 3–4 immune-related toxicity among 393 patients treated with ipilimumab and radiation for metastatic prostate cancer.(10) Notably, CA184-043 differed from the current trial in radiation dose (8 Gy in 1 fraction) and treatment site (bone metastases only).

To date, ipilimumab has had limited efficacy against cancers other than cutaneous melanoma.(10, 11, 23) Slovin et al. reported on 44 men with prostate cancer treated with 3–10 mg/kg ipilimumab and 8 Gy in 1 fraction administered to a bone metastasis.(11) Among 22 patients receiving both radiation and ipilimumab and exhibiting evaluable disease, an objective response rate was observed in 1 patient (5%).(11) In a phase II study investigating ipilimumab for pancreatic cancer, Royal et al. reported no objective responses.(23) In contrast, ipilimumab monotherapy has produced objective response rates of 10%–15% for patients with melanoma.(20, 21, 24–26) Notably, none of the patients in the current study were treated for cutaneous melanoma; rather, they were heavily pretreated with a variety of tumor types.

With regard to PBMCs, preclinical analyses have identified CD8+ T-cells as the primary mediator of radiation-induced systemic response.(3, 5, 7, 8) We observed increases in peripheral CD8+ T-cells and in the CD8+/CD4+ ratio over baseline levels in patients who achieved clinical benefit, suggesting systemic mobilization or a shift in the relative proportions of these populations. Although not statistically significant, there may also be an increase in the lymphocyte in patients who achieved clinical benefit. Clinical benefit in our study was also associated with changes in the expression profile of surface markers, specifically an increased proportion of CD8+ cells expressing 4-1BB and PD1. Twyman-Saint Victor et al. analyzed peripheral CD8+ T-cells after radiation and ipilimumab and identified an increase Ki67+GzmB+ population of PD-1+Eomes+ CD8+ T-cells to be associated with objective response, but also noted that the PD-1+Eomes+ CD8+ T-cells reflected the exhausted T-cell population.(3) Recent evidence also suggests that peripheral lymphocytes expressing PD1 represent the cancer antigen–specific T-cell population.(27) A possible explanation for our findings includes the early emergence of activated, tumor-directed CD8+ T-cells after SABR among patients who achieve clinical benefit.

The optimal timing and targeting of radiation with immunotherapy for metastatic disease remain unclear.(18, 28) Although our analysis did not reveal differences in PBMC activation according to the sequence of therapy, substantial differences were observed after hepatic versus lung irradiation. Hepatic radiation was associated with increased proportions of CD8+ T-cells expressing ICOS, GITR, and LAG3 and increased proportions of CD4+ Treg cells expressing 4-1BB, GITR, TIM-3, and PD1. Activation of ICOS, GITR, and 4-1BB has been shown to promote pro-immune activity.(29, 30) Conversely, activation of LAG3, TIM-3, and PD1 by appropriate ligands leads to immune inhibition.(31, 32) We interpret the current findings as suggesting that hepatic irradiation increases early systemic immune activation relative to lung radiation, as indicated by increasing proportions of T-cells expressing antigens with pro-immune function and compensatory increases in antigens with inhibitory functions. Whether this increased immune activation with liver irradiation can translate to increased clinical benefit may depend on overcoming the compensatory increase in markers with inhibitory function, or strategies to sustain systemic activation. Antibodies designed to activate GITR, 4-1BB, and ICOS that also inhibit PD1, LAG3, and TIM-3 are either being developed or are already in clinical use.(33)

Additional information on treatment efficacy is currently being obtained in the phase II portion of this study, and thus we did not compare response frequency between treatment groups. Given the low numbers of patients in the current study, we acknowledge that we are unable to detect smaller changes in PBMC numbers or surface marker expression. Analysis of immune markers should be considered hypothesis-generating because no adjustments were made for multiple testing. In addition, potential confounders include our treatment of a variety of different tumor types, which exhibit different propensities and size for liver metastasis, differences in the burden of irradiated and un-irradiated disease, and variations in prior systemic therapies. Finally, it is not possible based on the current analysis to assess whether responses outside of the radiation field were due to combination ipilimumab and radiation or to the effects of either modality alone.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that combination ipilimumab and high-dose SABR is tolerable and has encouraging clinical benefit outside the radiation field, that liver irradiation may be associated with greater systemic immune activation than lung, and that early increase in peripheral CD8+ T-cells and expression of 4-1BB and PD-1 on CD8+ T-cells may predict clinical benefit. These data are suggestive of additional immune checkpoint targets and clinical markers that that may help optimize treatment efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Translational Relevance.

Ipilimumab has shown limited efficacy in cancers outside of melanoma. In addition there is significant interest in combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with radiation to produce the abscopal effect, especially with ablative doses of radiation. We present the first phase I clinical trial combining stereotactic ablative radiation (SABR) with ipilimumab, while varying the radiation target (lung and liver lesion) and sequencing of radiation with immunotherapy (SABR initiated day after first dose or week after second dose of ipilimumab). We show that combination immunotherapy and SABR is safe and produces clinical responses in patients with non-melanoma histologies. We also present a comprehensive profile of the peripheral T-cell population and present correlates between the number and surface marker expression of these populations with achievement of clinical benefit and choice of radiation target.

Acknowledgments

Bristol-Myers Squibb provided the ipilimumab; the Immunotherapy Platform at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center performed the immune monitoring studies; and Cancer Center Support (Core) Grant NCI CA016672. We would like to thank Christine Wogan for assistance in editing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Tang C, Wang X, Soh H, Seyedin S, Cortez MA, Krishnan S, et al. Combining radiation and immunotherapy: a new systemic therapy for solid tumors? Cancer immunology research. 2014;2:831–838. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crittenden M, Kohrt H, Levy R, Jones J, Camphausen K, Dicker A, et al. Current clinical trials testing combinations of immunotherapy and radiation. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2015;25:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Twyman-Saint Victor C, Rech AJ, Maity A, Rengan R, Pauken KE, Stelekati E, et al. Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature. 2015;520:373–377. doi: 10.1038/nature14292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reits EA, Hodge JW, Herberts CA, Groothuis TA, Chakraborty M, Wansley EK, et al. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:1259–1271. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demaria S, Ng B, Devitt ML, Babb JS, Kawashima N, Liebes L, et al. Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2004;58:862–870. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golden EB, Chhabra A, Chachoua A, Adams S, Donach M, Fenton-Kerimian M, et al. Local radiotherapy and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to generate abscopal responses in patients with metastatic solid tumours: a proof-of-principle trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:795–803. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demaria S, Kawashima N, Yang AM, Devitt ML, Babb JS, Allison JP, et al. Immune-mediated inhibition of metastases after treatment with local radiation and CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model of breast cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11:728–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Y, Auh SL, Wang Y, Burnette B, Wang Y, Meng Y, et al. Therapeutic effects of ablative radiation on local tumor require CD8+ T cells: changing strategies for cancer treatment. Blood. 2009;114:589–595. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiess AP, Wolchok JD, Barker CA, Postow MA, Tabar V, Huse JT, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for melanoma brain metastases in patients receiving ipilimumab: safety profile and efficacy of combined treatment. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2015;92:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon ED, Drake CG, Scher HI, Fizazi K, Bossi A, van den Eertwegh AJ, et al. Ipilimumab versus placebo after radiotherapy in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer that had progressed after docetaxel chemotherapy (CA184-043): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:700–712. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70189-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slovin SF, Higano CS, Hamid O, Tejwani S, Harzstark A, Alumkal JJ, et al. Ipilimumab alone or in combination with radiotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: results from an open-label, multicenter phase I/II study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1813–1821. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filatenkov A, Baker J, Mueller AM, Kenkel J, Ahn GO, Dutt S, et al. Ablative Tumor Radiation Can Change the Tumor Immune Cell Microenvironment to Induce Durable Complete Remissions. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2015;21:3727–3739. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onishi H, Araki T, Shirato H, Nagata Y, Hiraoka M, Gomi K, et al. Stereotactic hypofractionated high-dose irradiation for stage I nonsmall cell lung carcinoma: clinical outcomes in 245 subjects in a Japanese multiinstitutional study. Cancer. 2004;101:1623–1631. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang JY, Li QQ, Xu QY, Allen PK, Rebueno N, Gomez DR, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiation therapy for centrally located early stage or isolated parenchymal recurrences of non-small cell lung cancer: how to fly in a "no fly zone". International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2014;88:1120–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timmerman R, McGarry R, Yiannoutsos C, Papiez L, Tudor K, DeLuca J, et al. Excessive toxicity when treating central tumors in a phase II study of stereotactic body radiation therapy for medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:4833–4839. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolchok JD, Hoos A, O'Day S, Weber JS, Hamid O, Lebbe C, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2009;15:7412–7420. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carthon BC, Wolchok JD, Yuan J, Kamat A, Ng Tang DS, Sun J, et al. Preoperative CTLA-4 blockade: tolerability and immune monitoring in the setting of a presurgical clinical trial. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2010;16:2861–2871. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernstein MB, Krishnan S, Hodge JW, Chang JY. Immunotherapy and stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (ISABR): a curative approach? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin JY, Kong FM, Chetty IJ, Ajlouni M, Ryu S, Ten Haken R, et al. Impact of fraction size on lung radiation toxicity: hypofractionation may be beneficial in dose escalation of radiotherapy for lung cancers. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2010;76:782–788. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson CM, Lim M, Drake CG. Immunotherapy for brain cancer: recent progress and future promise. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2014;20:3651–3659. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, O'Day S, Weber J, Garbe C, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peltomaki P. Deficient DNA mismatch repair: a common etiologic factor for colon cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:735–740. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Royal RE, Levy C, Turner K, Mathur A, Hughes M, Kammula US, et al. Phase 2 trial of single agent Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) for locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Journal of immunotherapy. 2010;33:828–833. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181eec14c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, Robert C, Grossmann K, McDermott D, et al. Nivolumab and Ipilimumab versus Ipilimumab in Untreated Melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2015 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;372:2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon S, Vignard V, Florenceau L, Dreno B, Khammari A, Lang F, et al. PD-1 expression conditions T cell avidity within an antigen-specific repertoire. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1104448. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1104448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalbasi A, June CH, Haas N, Vapiwala N. Radiation and immunotherapy: a synergistic combination. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:2756–2763. doi: 10.1172/JCI69219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallin JJ, Liang L, Bakardjiev A, Sha WC. Enhancement of CD8+ T cell responses by ICOS/B7h costimulation. J Immunol. 2001;167:132–139. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronchetti S, Nocentini G, Bianchini R, Krausz LT, Migliorati G, Riccardi C. Glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein lowers the threshold of CD28 costimulation in CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:5916–5926. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grosso JF, Kelleher CC, Harris TJ, Maris CH, Hipkiss EL, De Marzo A, et al. LAG-3 regulates CD8+ T cell accumulation and effector function in murine self- and tumor-tolerance systems. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:3383–3392. doi: 10.1172/JCI31184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez-Fueyo A, Tian J, Picarella D, Domenig C, Zheng XX, Sabatos CA, et al. Tim-3 inhibits T helper type 1-mediated auto- and alloimmune responses and promotes immunological tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1093–1101. doi: 10.1038/ni987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melero I, Grimaldi AM, Perez-Gracia JL, Ascierto PA. Clinical development of immunostimulatory monoclonal antibodies and opportunities for combination. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19:997–1008. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.