Abstract

Objective

This study's aim was to develop and standardize a Korean version (SCoRS-K) of the Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale (SCoRS), which is used to evaluate the degree of cognitive dysfunction affecting the everyday functioning of people with schizophrenia.

Methods

Eighty-four schizophrenia patients with stable symptoms who were receiving outpatient treatment and rehabilitation therapy, and 29 demographically matched non-patient controls, participated in the study. Demographic data were collected, and clinical symptoms, cognitive function, and social function were evaluated to verify SCoRS-K's reliability and validity. Clinical symptoms were evaluated using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale and the Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia Scale. Cognitive function was evaluated using a short form of the Korean Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST). Social function was evaluated using the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale, and the Social Functioning Scale.

Results

Data analysis demonstrated SCoRS-K's statistically significant reliability and validity. SCoRS-K has high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha; patient 0.941, informant 0.905, interviewer 0.964); test-retest reliability [patient 0.428 (p=0.003), informant 0.502 (p<0.001), interviewer 0.602 (p<0.001); and global rating 0.642 (p<0.001)]. The mean scores of subjects were significantly higher than those of the controls (p<0.001), demonstrating SCoRS-K's discriminant validity. Significant correlations between the total scores and global rating score of SCoRS-K and those of the scales and tests listed above (except WCST) support SCoRS-K's concurrent validity.

Conclusion

SCoRS-K is a useful instrument for evaluating the degree of cognitive dysfunction in Korean schizophrenia patients.

Keywords: Cognitive function, Reliability, Validity, Schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Cognitive dysfunction is a major symptom of schizophrenia,1 and it manifests in the areas of attention and executive function as well as linguistic and non-linguistic memory.2 A substantial number of schizophrenia patients present cognitive dysfunction from the prodromal stage, and cognitive dysfunction can be found in most patients who have experienced initial and recurrent episodes.3 Cognitive dysfunction is associated with both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia4 and patients' prognoses.5 Further, cognitive dysfunction can affect the everyday functioning of people with schizophrenia.6 Therefore, improving cognitive function is a significant goal in the treatment of schizophrenia, and there is much interest in the development of drugs to improve the cognitive function of people with schizophrenia.

In 2008, the expert panel of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) reported the results of the National Institute of Mental Health's Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB). The goal of the MCCB was to develop a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials of cognition-enhancing treatments for schizophrenia through a broadly based scientific evaluation of measures to assess basic cognitive function in individuals with schizophrenia.7 Many recent studies of the cognitive function of people with schizophrenia have used the MCCB.

However, a series of cognitive function tests in clinical settings is costly in terms of time and money, and training is needed to interpret the test results accurately. Moreover, cognitive function tests are limited in their ability to explain everyday functioning directly. For example, supports for a patient or assistance with their financial situation, and the absence or presence of occupational or psychosocial rehabilitation therapy are intertwined with cognitive function, and they can affect the everyday life of a patient. A cognitive function test needs to be readily applicable in actual clinical settings and useful in explaining clearly the connections between cognitive function and everyday functioning.

Studies of various tools to evaluate cognitive function in everyday life (and their validity) fall into two major categories. One category evaluates cognitive function through interview, and the other evaluates functional capacity through tests. Green et al.8 verified the reliability, validity, and appropriateness in clinical settings of two cognitive function evaluation scales through interviews with schizophrenia patients, and two skill capacity evaluation tools. The cognitive function evaluation scales were the Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale (SCoRS),9 which also interviewed informants, and the Clinical Global Impression of Cognition in Schizophrenia (CGI-SCH),10 which also interviewed carers. The skill capacity evaluation tools were the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Performance-Based Skills Assessment (UPSA)11 and the Maryland Assessment of Social Competence (MASC).12

Of the four tools listed above, SCoRS has been assessed as having high reliability and validity, particularly in the evaluation of cognitive dysfunction affecting the daily life of patients with schizophrenia, although its validity is reduced when the patient's self-report is the sole information source.13 SCoRS assesses the patient's attention, memory, inference and problem solving skills, working memory, language production, and motor skills.14 In contrast with previous interview-based cognitive function tests that found it difficult to relate results to daily life as they interviewed subjects only, SCoRS overcame this limitation by interviewing informants as well as patients.9 SCoRS was verified as a useful evaluation tool for Asian patients with schizophrenia in a Singaporean English-language study,14 and a Japanese version is widely used in Japan to evaluate the cognitive function of patients with schizophrenia.15

This study was designed to develop a Korean version of SCoRS in order to evaluate appropriately the degree of cognitive dysfunction affecting the everyday functioning of Korean patients with schizophrenia, and to standardize the Korean version through tests of reliability and validity.

METHODS

Subjects

Based on the diagnosis standard of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),16 the study subjects were patients diagnosed with schizophrenia aged between 18 and 60 years, with stable symptoms, who had been taking the same dose of antipsychotics for the past three months, and who had been receiving rehabilitation therapy as outpatients. Patients with mental disorders other than schizophrenia (bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and organic mental disorder); patients with neurological disorders (head injuries or a seizure disorder); patients with a history of alcohol or drug abuse; and patients whose intelligence level was not sufficient to undertake the cognitive function tests were excluded from the study. People who matched the subjects for age, sex, and educational level and who had no history of mental disorder were selected as the control group.

Bonett's method was used to determine the optimum sample size.17 Eighty-four patients with schizophrenia and 29 non-patient controls participated in the study.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Research at Inje University Busan Paik Hospital.

Measures

The duration of the subjects' illness and the types and doses of current medications were identified through medical record review, and the doses of antipsychotics were converted into a chlorpromazine equivalent dose.18,19 Experienced psychiatrists conducted face-to-face interviews with the subjects and the members of the control group. Cognitive function was evaluated using a short form of the Korean Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (K-WAIS) and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST). Clinical symptoms were evaluated using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and the Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia Scale (CGI-SCH). Social function was evaluated using the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS), the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale (SQLS), and the Social Functioning Scale (SFS).

The Korean version of the Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale

The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale (SCoRS) developed by Keefe et al.9 is an assessment tool that focuses on cognitive dysfunction in people with schizophrenia and its relationship to their real-world functioning and functional capacity. It was developed to assess difficulties in attention, memory, motor skills, language production, and problem solving, and the cognitive difficulty experienced by subjects during the two weeks prior to interview. People with schizophrenia and informants respond to 20 items, and their responses are scored on a four-point scale, with higher scores denoting more severe dysfunction. The test takes approximately 30 minutes to administer.

Written pre-approval to develop a Korean version, SCoRS-K, was obtained from the primary original author, R S Keefe, and a professional translator translated SCoRS into Korean. A research committee of four psychiatrists, including the principal investigator, finalized the first edition after thorough discussion and revision. The text was back-translated into English by a professional translator and reviewed by the original developer to confirm that the intentions of the original author were accurately reflected in the back-translated version.

In the original study by Keefe et al.9 global ratings were identified for three groups-patient, informant, and interviewer- and the scores were compared. In a recent study,14 the sum of the 20 SCoRS items (the SCoRS total) was found to be meaningful, and the SCoRS total was included in addition to global ratings in the analysis in this study.

The short form of the Korean Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale

K-WAIS is a standardized cognitive test, a Korean version of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R), which is used to evaluate verbal and performance intelligence. This study used a short form of K-WAIS, consisting of picture completion, arithmetic, digit span, and similarities. In a previous study comparing short-form tests of cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia, the short-form tests were more readily administered than full tests, and there was a high correlation between estimated intelligence and WAIS-R-measured intelligence.20

The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Computer Version 4

The WCST developed by Heaton21 was used in the interviews. WCST is a representative test that measures executive function, with an emphasis on perseverance and achievement. The test uses 128 cards that have combinations of four colors, shapes, and numbers. The interviewee must deduce the classifications of the cards first, and then find the changing pattern of one category among color, shape, and number, without any explanation from the interviewer during the test.

The Korean version of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

PANSS is a psychopathology evaluation tool developed by Kay et al.22 that provides “a balanced representation of positive and negative symptoms and gauges their relationship to one another,” and to global psychopathology. It is a 30-item, seven-point rating instrument; seven items assess positive symptoms, seven items assess negative symptoms, and 16 items assess general psychopathology. Higher scores denote more severe psychopathologic conditions. In the current study, a psychiatrist evaluated the patient group using K-PANSS, the Korean version of the test.23

The scores in each category of the five-factor model of PANSS proposed by van der Gaag et al.24 were also obtained. The five-factor model consists of positive symptoms, negative symptoms, cognitive/disorganization symptoms, excitement, and emotional distress.

The Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia Scale

The Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia scale (CGI-SCH) has been developed as a short, standardized method of assessing the symptoms of schizophrenia in a clinical setting. It consists of two categories; severity of illness and degree of change, each of which rate five dimensions (positive, negative, depressive, cognitive and global) that are evaluated using a seven-point scale.25

The Korean Version of the Social Functioning Scale

The Social Functioning Scale (SFS) was developed by Birchwood et al.26 to assess the self-reported ability of people with schizophrenia to manage social interactions, relationships, and activities of daily life. The scale investigates seven areas including social withdrawal, relationships, social activities, recreational activities, independence (competence), independence (performance), and employment. This study used KSRS, the Korean version of the Social Functioning Scale.27

The Korean language version of the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale-fourth revision

The Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale-fourth revision (SQLS-R4) is a short, self-report quality of life questionnaire, that is generally completed within five to ten minutes.28 It consists of disease-specific items reflecting the daily lives of people with schizophrenia. A higher score denotes a lower quality of life. It comprises 33 items, and the maximum score is 132 points, which is converted to a 100-point scale. This study used the Korean language version of SQLS-R4 (SQLS-R4K).29

The Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale

SOFAS30 assesses the individual's level of social and occupational functioning at the time of the interview, without being directly influenced by the individual's psychological symptoms. However, impairment from general medical conditions is considered in the assessment, which ranges along a continuum from “very outstanding” to “remarkably impaired.” In this study, a psychiatrist evaluated functional level after interview.

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables are reported as means, standard deviations, and ranges, and discrete variables are given as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between patients with schizophrenia and controls were performed using t-tests, chi-square tests, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests depending on the characteristics of each variable.

Validity was tested through the following methods. For discriminant validity, the SCoRS scores of the subjects and the control group were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. For concurrent validity, the correlations between SCoRS-K and K-WAIS, WCST, PANSS, CGI-SCH, SFS, SQLS, and SOFAS were verified using Pearson's correlation coefficient. Test-retest reliability was evaluated using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), and the internal consistency in each area was tested using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. The test-retest reliability was performed twice for the subjects, with a one-month interval between them.

All analyses were carried out using Statistical Analysis System 9.3 package (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and the significance level was set at 0.05 or below.

RESULTS

Demographic data

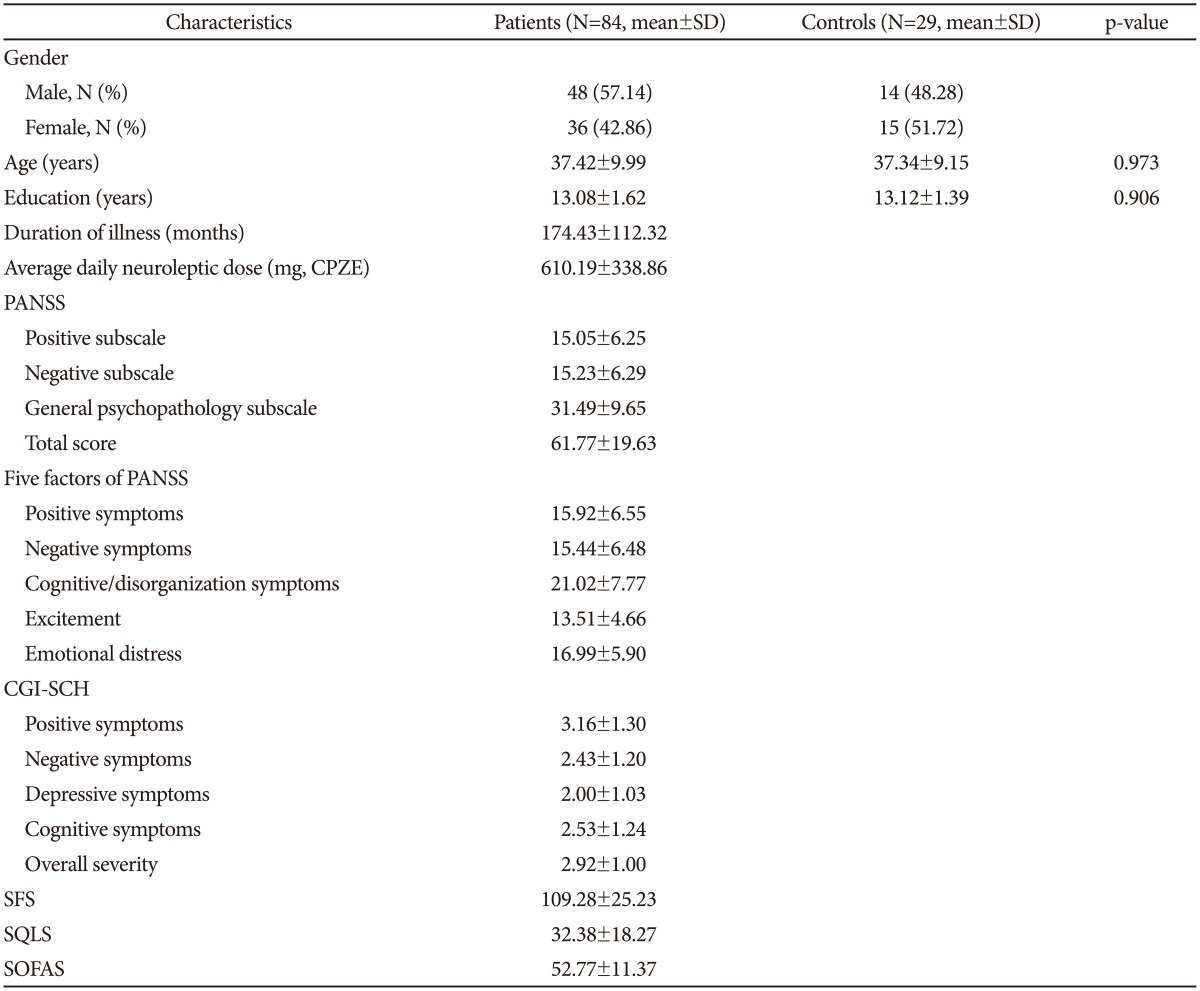

The comparison between the demographic data of the patient group and the control group is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with schizophrenia and controls.

CGI-SCH: Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia, CPZE: chlorpromazine equivalent, PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, SD: standard deviation, SFS: Social Functioning Scale, SOFAS: Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, SQLS: Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale

There was a higher ratio of males to females in the patient group (57.14% to 42.86%) compared with the control group (48.28% to 51.72%). The mean age of the two groups was closely comparable, at 37.42±9.99 years for the patient group, and 37.34±9.15 years for the control group. The two groups' years of education were also closely comparable, at 13.08±1.62 years for the patient group and 13.12±1.39 years for the control group. The patient group had experienced schizophrenia over the long term; the mean duration of illness was 174.43±112.32 months, and the dosage of antipsychotics, converted to the chlorpromazine equivalent dose, was 610.19±338.86 mg/day.

Clinical characteristics and cognitive function

Patient-only test

The results from the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), the Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia Scale (CGI-SCH), the Social Functioning Scale (SFS), the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale (SQLS), and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) are also presented in Table 1 above.

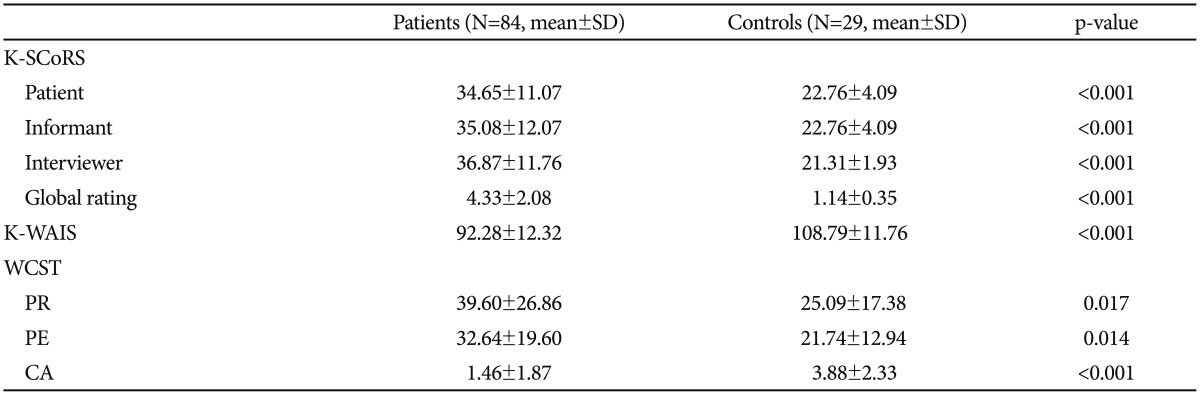

Patient and control group tests

The results for the short-form Korean version of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (K-WAIS) and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) are presented in Table 2. The patient and control group results for K-WAIS were significantly different, at 92.28±12.32 for patients and 108.79±11.76 for controls (p<0.001). For the three categories in the WCST (perseverative responses, perseverative errors and categories achieved) only the latter demonstrated a statistically significant difference between the patient group and the control group, at 1.46±1.87 for the patient group and 3.88±2.33 for the control group (p<0.001).

Table 2. Comparison of patients with schizophrenia and controls for cognitive function.

CA: numbers of categories achieved, K-SCoRS: Korean version of Schizophrenia Cognitive Rating Scale, K-WAIS: Short-form of Korean-Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, PE: perseverative errors, PR: perseverative responses, SD: standard deviation, WCST: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

Discriminant validity

There was a statistically significant difference for cognitive function between the patient group and the control group in all the SCoRS-K results (p<0.001), as shown in Table 2 above. This included interviewees' responses (34.65±11.07 for patients and 22.76±4.09 for the control group), interviewers' responses (36.87±11.76 for patients and 21.31±1.93 for the control group), and global rating (4.33±2.08 for patients and 1.14±0.35 for the control group).

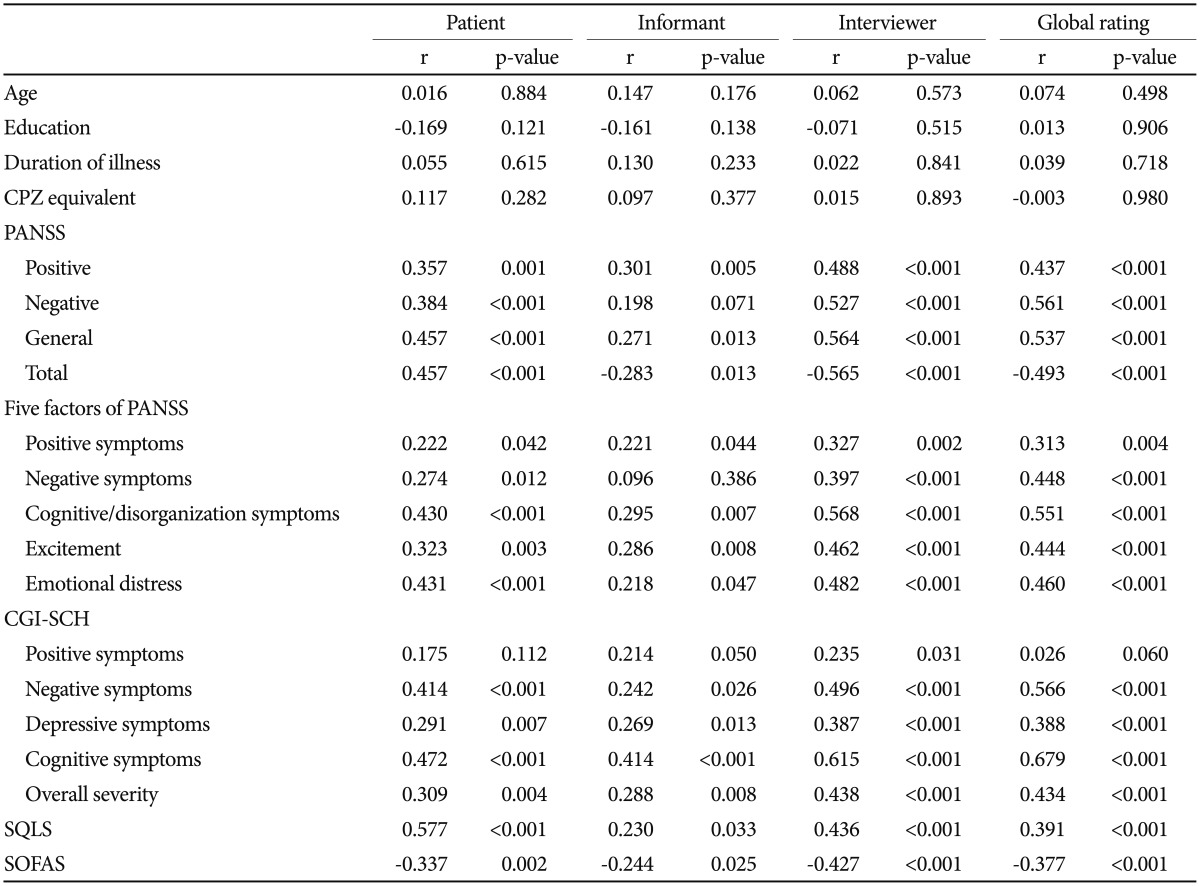

Concurrent validity

Correlation between SCoRS-K and clinical characteristics

Correlations between SCoRS-K and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 3. Patients' SCoRS-K scores correlated significantly with global ratings on the PANSS' positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and general psychopathology subscales (p<0.001); however, SCoRS-K scores were not significantly correlated with informants' responses. Regarding the five-factor PANSS model, patients' SCoRS-K scores correlated significantly with scores on the cognitive/disorganization symptoms and emotional distress factors; additionally, interviewers' responses and global ratings correlated significantly with scores on negative symptoms, cognitive/disorganization symptoms, excitement, and emotional distress (ps<0.001). Scores on the SCoRS-K correlated significantly with scores on all of the CGI-SCH's global rating categories except positive symptoms; however, numerous other categories under patients' and informants' responses were positively correlated with patients' SCoRS-K scores (p<0.001).

Table 3. Correlation between K-SCoRS and demographic/clinical characteristics of patients with schizophrenia.

CGI-SCH: Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia, CPZE: chlorpromazine equivalent, K-SCoRS: Korean version of Schizophrenia Cognitive Rating Scale, PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, SOFAS: Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, SQLS: Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale

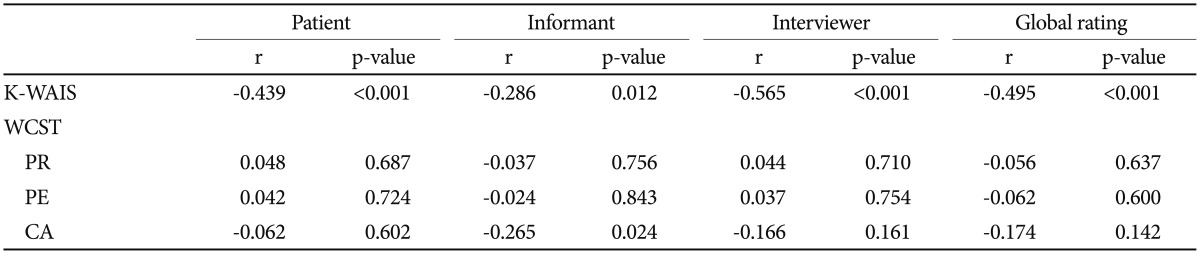

Correlation between SCoRS-K and cognitive function

Table 4 presents the results for K-WAIS and WCST correlations with SCoRS-K. Patients' and interviewers' responses and global rating scores correlated significantly with patients' K-WAIS scores (p<0.001). No significant correlations were detected regarding the WCST.

Table 4. Correlation between K-SCoRS and cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia.

CA: numbers of categories achieved, K-SCoRS: Korean version of Schizophrenia Cognitive Rating Scale, K-WAIS: Short-form of Korean-Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, PE: perseverative errors, PR: perseverative responses, WCST: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

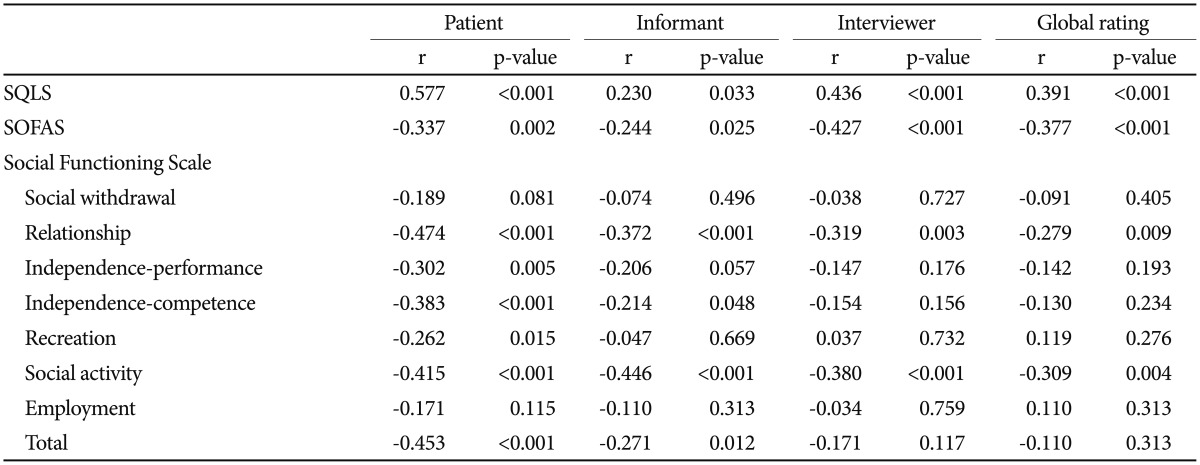

Correlation between SCoRS-K and social function

Correlations between SCoRS-K and social function are presented in Table 5. Patients' SCoRS-K scores correlated significantly with patients and interviewers' SQLS scores and with patients' global SQLS rating. Regarding the SOFAS, SCoRS-K scores also correlated significantly with patients and interviewers' scores and with patients' global rating (ps<0.001). Regarding the SFS, significant correlations were detected for patients, informants, and interviewers' total ratings, but not for global rating (ps<0.001).

Table 5. Correlation between K-SCoRS and social functioning in patients with schizophrenia.

K-SCoRS: Korean version of Schizophrenia Cognitive Rating Scale, SOFAS: Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, SQLS: Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale

Inter-rater reliability

Two interviewers (S.S. Jung and D.U. Jung) participated in the same interviews of 13 patients. Intra-class correlations of the relationship between the ratings generated by the two interviewers were calculated to assess interrater reliability. The intra-class correlation coefficients for items were greater than 0.931.

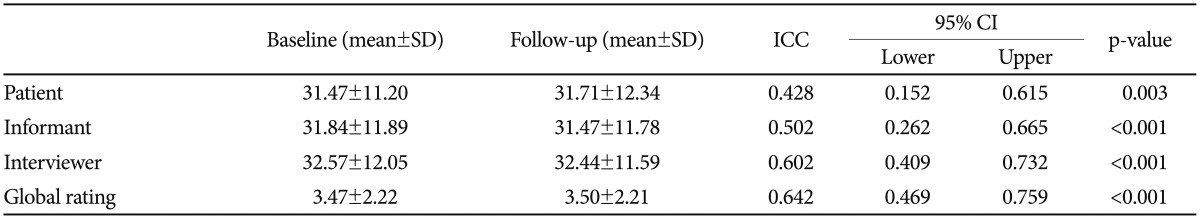

Test-retest reliability

Table 6 records high test-retest reliability at the one-month follow-up for intra-class correlation coefficients calculated for the patient, informant, interviewer, and SCoRS-K global rating scores.

Table 6. Test-retest reliability.

ICC: intra-class correlation coefficient, CI: confidence interval

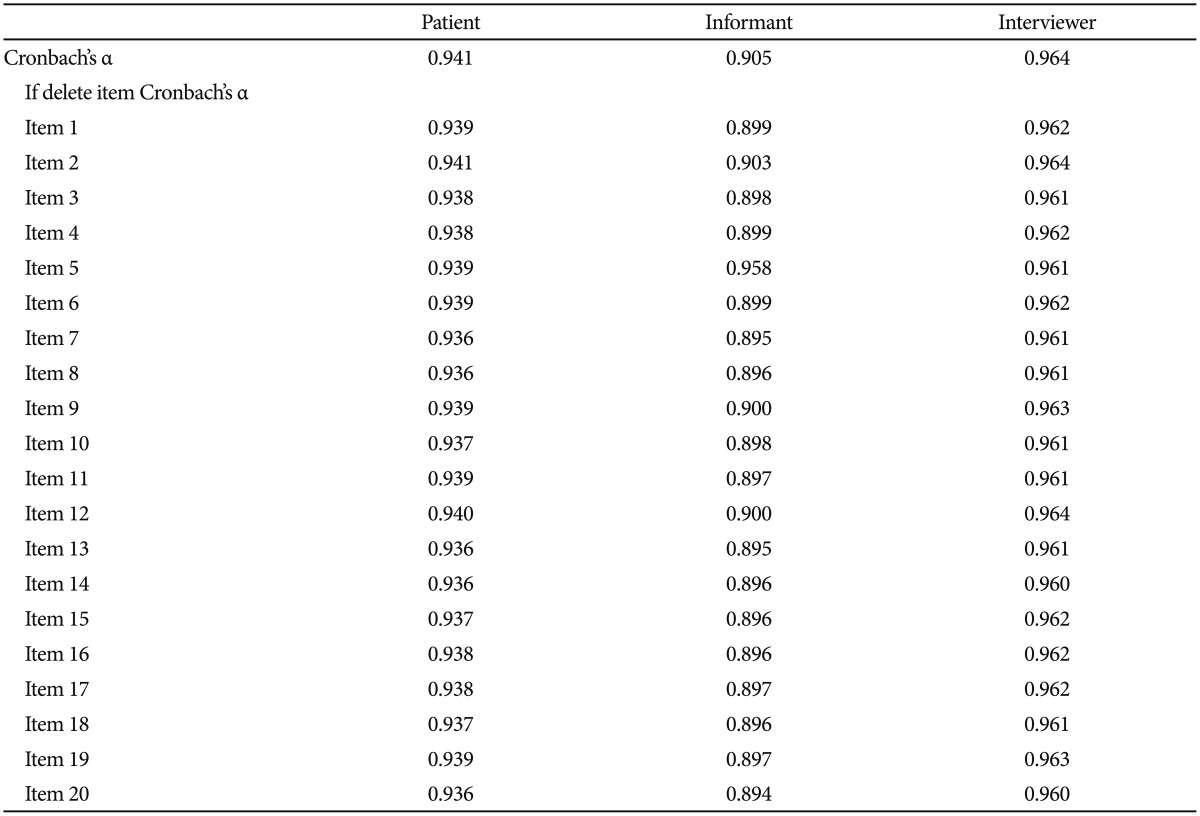

Internal consistency

Cronbach's alpha is recorded in Table 7, and demonstrates high internal consistency for the three evaluation components of patient, informant, and interviewer. There was no item for which Cronbach's alpha improved when any one of 20 questions was excluded. There were no items whose deletion improved the overall internal consistency of the scale by more than 0.01.

Table 7. Cronbach's alpha.

DISCUSSION

This study's aim was to develop and standardize a Korean version (SCoRS-K) of the Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale (SCoRS), which is used to evaluate the degree of cognitive dysfunction affecting the everyday functioning of patients with schizophrenia.

There were many differences between the scores for patients' responses and informants' responses in the original development and validation of SCoRS by Keefe et al.9 and in those cases interviewers tended to give greater weight to informants' responses than patients'. However, in this study, patients' response scores were similar to interviewers' scores, while informants' scores tended to be different. A number of patients in Korea live with their family unless they are hospitalized and all participants in this study lived with their parents to an advanced age. Most informants in this study were older parents, and the interviewers, who were the patients' primary care doctors or managers in rehabilitation therapy centers, were more knowledgeable about the patients' conditions than the informants were that contrary to expectations. The person with schizophrenia lives with their family in this study, therefore, we might expect them to have a close knowledge of the person's day-to-day functioning.

In order to examine the validity of SCoRS-K in measuring clinical symptoms, the study investigated if there was any correlation between the scores of patients', informants', and interviewers' responses and global ratings in SCoRS-K, and the scales for clinical symptoms in PANSS, CGI-SCH, SQLS and SOFAS. When PANSS was classified into positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and general psychopathology, there were significant correlations with interviewers' scores for all items. When PANSS was evaluated by the five-factor model for a more precise classification, there were significant correlations with interviewers' scores for all items except positive symptoms. For CGI-SCH also, there were significant correlations with the interviewers' scores for all items except positive symptoms. As in this study, the correlation between the clinical symptoms of patients with schizophrenia and cognitive function has been verified in a number of previous studies.31,32 A substantial number of studies have reported a lack of correlation between positive symptoms and cognitive function.2,33

The correlation between SCoRS-K results and cognitive function varied depending on the focus of the different tests used. Significant correlations were found between SCoRS-K and K-WAIS in all cases except for informants' responses; therefore, it may be inferred that SCoRS-K appropriately reflects cognitive function. However, a significant correlation was not identified between SCoRS-K and any items in WCST. WCST is a representative of tests used to measure executive function, while SCoRS is a test to evaluate overall cognitive function (including but not exclusively executive function) in the everyday lives of people with schizophrenia, which may be the reason why there was no significant correlation. Keefe et al.13 conducted a study about the validity of the SCoRS. In that study, the SCoRS interviewers' scores had a significant relationship with cognitive function as measured by the MCCB. Another study found that the SCoRS global rating scores are related with the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) composite scores and most of the BACS sub-test scores.14

The correlation between SCoRS-K results and social function, as measured by SQLS and SOFAS, showed significant correlations for interviewers' responses. The KSFS demonstrated correlations with SCoRS-K for a number of items, and significant correlations for the responses of patients, informants, and interviewers to the item about social activity (Table 5). This suggests that SCoRS-K is a test whose evaluation range includes measuring social functioning in daily life rather than merely a cognitive function test.

Both inter-rater reliability and internal consistency were sufficient, and reflected the results obtained by the original authors.9 Test-retest reliability at one month was high (p<0.001) except for patients' responses, which were relatively low (p=0.003). However, patients' self-reports are often not consistent, and informants' and interviewers' responses and global rating all had high test-retest reliability, indicating SCoRS-K's high stability.

This study verifies SCoRS-K's high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and discriminant and concurrent validity. SCoRS-K will be a verified and useful tool for future studies of the degree of cognitive dysfunction affecting the everyday functioning of Korean patients with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by 2015 Inje University Busan Paik Hospital research grant.

References

- 1.Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ. Neurocognition in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:315–336. doi: 10.1037/a0014708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nieuwenstein MR, Aleman A, de Haan EH. Relationship between symptom dimensions and neurocognitive functioning in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of WCST and CPT studies. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Continuous Performance Test. J Psychiatr Res. 2001;35:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corigliano V, De Carolis A, Trovini G, Dehning J, Di Pietro S, Curto M, et al. Neurocognition in schizophrenia: from prodrome to multi-episode illness. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman I, Viegner B, Merson A, Allan E, Pappas D, Green AI. Differential relationships between positive and negative symptoms and neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1997;25:1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(96)00098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verdoux H, Liraud F, Assens F, Abalan F, van Os J. Social and clinical consequences of cognitive deficits in early psychosis: a two-year follow-up study of first-admitted patients. Schizophr Res. 2002;56:149–159. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green MF, Kern RS, Heaton RK. Longitudinal studies of cognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: implications for MATRICS. Schizophr Res. 2004;72:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD, et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:203–213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Kern RS, Baade LE, Fenton WS, Gold JM, et al. Functional co-primary measures for clinical trials in schizophrenia: results from the MATRICS Psychometric and Standardization Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:221–228. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keefe RS, Poe M, Walker TM, Kang JW, Harvey PD. The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale: an interview-based assessment and its relationship to cognition, real-world functioning, and functional capacity. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:426–432. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ventura J, Cienfuegos A, Boxer O, Bilder R. Clinical global impression of cognition in schizophrenia (CGI-CogS): reliability and validity of a co-primary measure of cognition. Schizophr Res. 2008;106:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27:235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellack AS, Sayers M, Mueser KT, Bennett M. Evaluation of social problem solving in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103:371–378. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keefe RS, Davis VG, Spagnola NB, Hilt D, Dgetluck N, Ruse S, et al. Reliability, validity and treatment sensitivity of the Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chia MY, Chan WY, Chua KY, Lee H, Lee J, Lee R, et al. The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale: validation of an interview-based assessment of cognitive functioning in Asian patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaneda Y, Ueoka Y, Sumiyoshi T, Yasui-Furukori N, Ito T, Higuchi Y, et al. Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale Japanese version (SCoRS-J) as a co-primary measure assessing cognitive function in schizophrenia. Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2011;31:259–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association. D. S. M. Task Force. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonett DG, Wright TA. Sample size requirements for estimating pearson, kendall and spearman correlations. Psychometrika. 2000;65:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rey MJ, Schulz P, Costa C, Dick P, Tissot R. Guidelines for the dosage of neuroleptics. I: Chlorpromazine equivalents of orally administered neuroleptics. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1989;4:95–104. doi: 10.1097/00004850-198904000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O'Donnell H, Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:686–693. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09060802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen DN, Huegel SG, Gurklis JA, Jr, Kelley ME, Barry EJ, van Kammen DP. Utility of WAIS-R short forms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1997;26:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(97)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtiss G. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, Manual: Revised and Expanded. Odessa, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yi JS, Ahn YM, Shin HK, An SK, Joo YH, Kim SH, et al. Reliability and validity of the korean version of the positive and negative syndrome scale. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2001;40:1090–1105. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Gaag M, Hoffman T, Remijsen M, Hijman R, de Haan L, van Meijel B, et al. The five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale II: a ten-fold cross-validation of a revised model. Schizophr Res. 2006;85:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haro JM, Kamath SA, Ochoa S, Novick D, Rele K, Fargas A, et al. The Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia scale: a simple instrument to measure the diversity of symptoms present in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2003:16–23. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.107.s416.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R, Wetton S, Copestake S. The Social Functioning Scale. The development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:853–859. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim CK, Lee JA. Development of the Korean version of the social functioning scale in the schizophrenics: a study on the reliability and validity. Korean J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;16:76–111. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin CR, Allan R. Factor structure of the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale Revision 4 (SQLS-R4) Psychol Health Med. 2007;12:126–134. doi: 10.1080/13548500500407383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JH, Yim SJ, Min SK, Kim SE, Son SJ, Wild DJ, et al. The Korean version of 4th revision of schizophrenia quality of life scale: validation study and relationship with PANSS. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2006;45:401–410. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR. Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1148–1156. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liddle PF. Schizophrenic syndromes, cognitive performance and neurological dysfunction. Psychol Med. 1987;17:49–57. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700012976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuesta MJ, Peralta V. Cognitive disorders in the positive, negative, and disorganization syndromes of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1995;58:227–235. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02712-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strauss ME. Relations of symptoms to cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19:215–231. doi: 10.1093/schbul/19.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]