Abstract

Objective

To systematically explore the molecular mechanism for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) metastasis and identify regulatory genes with text mining methods.

Results

Genes with highest frequencies and significant pathways related to HCC metastasis were listed. A handful of proteins such as EGFR, MDM2, TP53 and APP, were identified as hub nodes in PPI (protein-protein interaction) network. Compared with unique genes for HBV-HCCs, genes particular to HCV-HCCs were less, but may participate in more extensive signaling processes. VEGFA, PI3KCA, MAPK1, MMP9 and other genes may play important roles in multiple phenotypes of metastasis.

Materials and methods

Genes in abstracts of HCC-metastasis literatures were identified. Word frequency analysis, KEGG pathway and PPI network analysis were performed. Then co-occurrence analysis between genes and metastasis-related phenotypes were carried out.

Conclusions

Text mining is effective for revealing potential regulators or pathways, but the purpose of it should be specific, and the combination of various methods will be more useful.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, metastasis, text mining

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second cause of death from malignancy tumor and the sixth most prevalent cancer worldwide [1]. Like many other types of malignance tumor, metastasis was considered the primary cause for treatment failure and HCC-associated mortalities [2, 3]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms involved in HCC metastasis would facilitate to develop novel strategies, such as personalized therapies and molecular-targeted drugs, which may help to improve the rate of survival.

A large number of genes and proteins have been examined for HCC metastasis. However, since metastasis is thought to be a multi-step process regulated by sophisticated molecular network, it is necessary to systematically assess the significance of each gene and find out the most important regulators.

Nowadays, text mining (TM) technology is increasingly applied for data analysis. In this study, we employed text mining technology and other bioinformatics methods to perform systematic analysis toward published articles, in order to figure out the critical genes and pathways for HCC metastasis, and to profile the unique regulations for HCCs with different etiologies such as HBV and HCV.

RESULTS

HCC metastasis-related genes and KEGG pathway analysis

According to text mining and frequency analysis, 1116 genes were identified within 8218 abstracts. The top 20 genes and their frequencies were listed in Table 1. Among these genes, VEGFA, AFP, CDH1, MMP2 and MMP9 were mentioned more than 150 times, while MAPK1, TGFB1, AKT1, CTNNB1 and other genes were also widely studied.

Table 1. The top 20 HCC metastasis-related genes based on text mining.

| Gene | Description | Count |

|---|---|---|

| VEGFA | vascular endothelial growth factor A | 252 |

| AFP | alpha fetoprotein | 190 |

| CDH1 | cadherin 1 (E-cadherin) | 154 |

| MMP2 | matrix metallopeptidase 2 | 154 |

| MMP9 | matrix metallopeptidase 9 | 153 |

| MAPK1 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | 123 |

| TGFB1 | transforming growth factor beta 1 | 118 |

| AKT1 | AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 | 110 |

| CTNNB1 | catenin beta 1 | 100 |

| PTK2 | protein tyrosine kinase 2 (FAK) | 93 |

| SPP1 | secreted phosphoprotein 1 | 85 |

| NME1 | NME/NM23 nucleoside diphosphate kinase 1 | 82 |

| NFKB1 | nuclear factor kappa B subunit 1 | 76 |

| MET | MET proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase | 75 |

| BSG | basigin (CD147) | 72 |

| PIK3CA | phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha | 71 |

| HIF1A | hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha subunit | 68 |

| CD44 | CD44 molecule | 67 |

| FN1 | fibronectin 1 | 65 |

| HGF | hepatocyte growth factor | 65 |

Only the genes that co-appeared with metastasis-related phenotypes in the same sentence will be counted. If a gene appeared several times in one sentence, it would be treated once.

KEGG pathway analysis was carried out with identified genes. The top 20 pathways were listed in Table 2, including focal adhesion, adherens junction, regulation of actin cytoskeleton, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction and so on.

Table 2. The most significant KEGG pathways related to HCC metastasis.

| KEGG Pathway | Genes | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Focal adhesion | 98 | < 0.0001 |

| Adherens junction | 42 | < 0.0001 |

| Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 71 | < 0.0001 |

| Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 78 | < 0.0001 |

| MAPK signaling pathway | 74 | < 0.0001 |

| Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 39 | < 0.0001 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Apoptosis | 32 | < 0.0001 |

| Cell cycle | 31 | < 0.0001 |

| Purine metabolism | 6 | < 0.0001 |

| Insulin signaling pathway | 40 | 0.0001 |

| Wnt signaling pathway | 40 | 0.0002 |

| Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction | 22 | 0.0002 |

| TGF-beta signaling pathway | 27 | 0.0002 |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | 3 | 0.002 |

| Tight junction | 30 | 0.002 |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 2 | 0.003 |

| Jak-STAT signaling pathway | 37 | 0.007 |

| Gap junction | 24 | 0.01 |

| Fatty acid metabolism | 2 | 0.01 |

Official symbols of all 1116 genes were treated as inputs. KEGG pathways were sorted by P value.

HCC metastasis-related PPI analysis

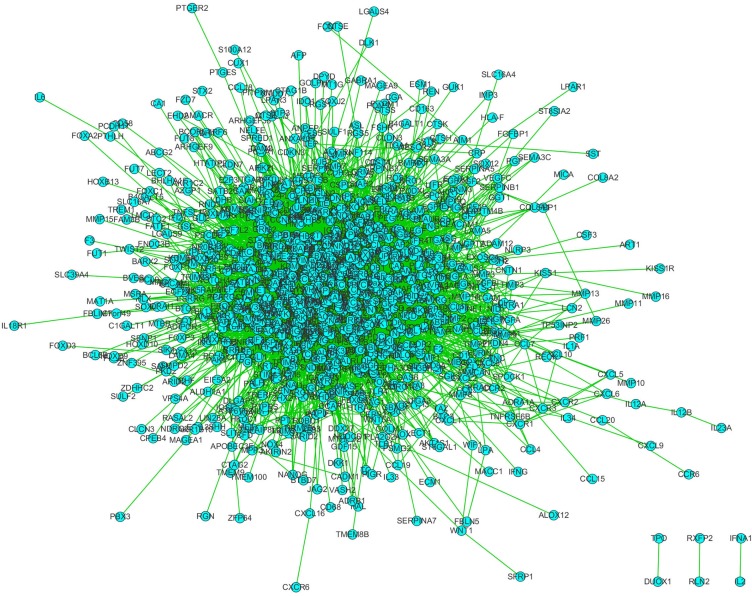

Critical regulators usually work as hub proteins in regulation network, so the PPI network among these proteins was generated and illustrated in Figure 1. The degree of nodes (the number of proteins interacting with it) was demonstrated in Table 3. The degree of UBC (ubiquitin C) is much higher than others’, which may partly be attributed to its function in protein degradation. EGFR (degree = 157), MDM2 (degree = 153), TP53 (degree = 152), APP (degree = 149), HSP90AA1 (degree = 149) and other proteins are also predicted as core nodes among the network.

Figure 1. The PPI network of HCC-metastasis related genes.

All edges were treated as undirected and all interactions were based on experiments. Isolated nodes and self-loops were deleted. Network was built with input nodes only, excluding their neighbours.

Table 3. The top 20 nodes in HCC metastasis-related PPI network.

| Node | Description | Degree |

|---|---|---|

| UBC | ubiquitin C | 739 |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor | 157 |

| MDM2 | MDM2 proto-oncogene | 153 |

| TP53 | tumor protein p53 | 152 |

| APP | amyloid beta precursor protein | 149 |

| HSP90AA1 | heat shock protein 90 alpha family class A member 1 | 149 |

| EP300 | E1A binding protein p300 | 135 |

| SUMO1 | small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 | 130 |

| GRB2 | growth factor receptor bound protein 2 | 128 |

| SRC | SRC proto-oncogene, non-receptor tyrosine kinase | 126 |

| CTNNB1 | catenin beta 1 | 125 |

| FN1 | fibronectin 1 | 123 |

| YWHAZ | tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein zeta | 122 |

| ESR1 | estrogen receptor 1 | 110 |

| HSP90AB1 | heat shock protein 90 alpha family class B member 1 | 107 |

| HDAC1 | histone deacetylase 1 | 100 |

| AKT1 | AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 | 96 |

| AR | androgen receptor | 92 |

| MAPK1 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | 88 |

| CUL7 | cullin 7 | 87 |

| MYC† | v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog | 87 |

The degree of each node was calculated with CytoNCA. All edges were treated as undirected. †MYC was equal with CUL7.

Metastasis of HCCs resulting from HBV or HCV

Chronic HBV or HCV infections now have been recognized as the major risk factors for the development HCC [4], but they take very different strategies for tumorigenesis. HBV DNA is integrated into the host genome and increases the HCC risk through several approaches such as increased levels of HBV proteins, transactivation of transcription factors, disruption of chromosomal stability and so on [5]. Instead, HCV has no integration into host DNA, neither direct oncogenic activity of its genes. Subsequent HCC always develops following liver fibrosis and cirrhosis [4, 6]. So HCCs caused by HBV or HCV may differ in metastasis mechanisms.

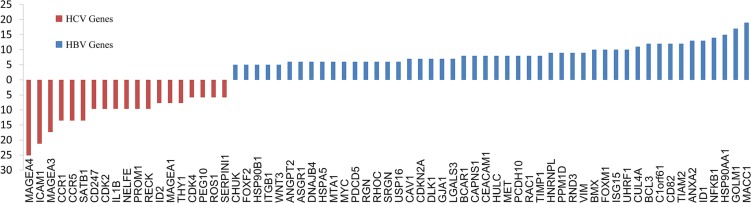

To verify this hypothesis, 286 genes were identified in Pubmed retrieves, 78 of which were shared by HBV and HCV papers, 165 particularly for HBV and 43 particularly for HCV. Genes uniquely mentioned with HBV or HCV were demonstrated in Figure 2, and their KEGG results were listed in Table 4. Besides the overlapping processes, HBV-particular genes were involved in MAPK pathway, tight junction and adherens junction. HCV-particular genes, by contrast, participated in more extensive signaling cascades, including TGF-beta, Jak-STAT, cell cycle, ECM-receptor interaction and gap junction, though the number of them was much less (43 VS 165).

Figure 2. Genes unique to HBV or HCV-related-metastasis.

Genes with low frequency (freq < 5) were excluded. As papers about HCV-metastasis were less than that of HBV (136 VS 262), all frequencies of HCV particular genes were normalized based on the number of papers (×1.926).

Table 4. The KEGG pathways for HBV/HCV particular genes related to metastasis.

| KEGG Pathway | Genes | P-Value | For HBV Particular Genes | For HCV Particular Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAPK signaling pathway | 15 | 0.0003 | Y | |

| Tight junction | 8 | 0.004 | Y | |

| Adherens junction | 6 | 0.007 | Y | |

| Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 7 | 0.0003 | Y | |

| TGF-beta signaling pathway | 4 | 0.0006 | Y | |

| ECM-receptor interaction | 3 | 0.005 | Y | |

| Jak-STAT signaling pathway | 4 | 0.005 | Y | |

| Gap junction | 3 | 0.007 | Y | |

| Cell cycle | 3 | 0.008 | Y | |

| Focal adhesion | 16/5 | < 0.0001/0.005 | Y | Y |

| Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 14/5 | 0.0003/0.003 | Y | Y |

| Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 7/3 | 0.006/0.008 | Y | Y |

As shown in the last two columns, pathways may belong to HBV/HCV-HCC metastasis particular genes, or shared by both.

Co-occurrence analysis with metastasis-related phenotypes

According to classical theory [7], metastasis can be roughly divided into several steps. Cancer cells have to depart from the original position, invade the extracellular matrix and enter vascular system, where they travel to other sites of body and eventually form new colonization [8, 9]. That is a real tough experience. Reasonably, if a gene can simultaneously affect more than one metastasis related phenotypes, its mutation or de-regulation is more likely to facilitate metastasis.

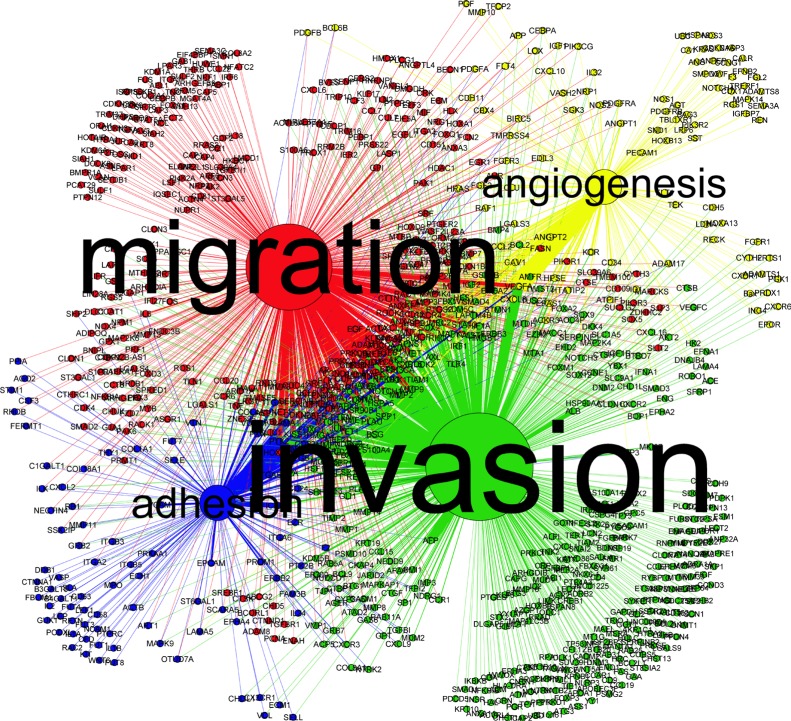

To identify these genes, four metastasis-related phenotypes were extracted from metastasis cascades. They were “adhesion”, “migration”, “invasion” and “angiogenesis”. The co-occurrence between these words and genes were examined, and the results were demonstrated in Figure 3. The mostly concerned phenotype was “invasion” (freq = 2786), and then “migration” (freq = 1826). “Adhesion” (freq = 696) and “angiogenesis” (freq = 561) had relatively low co-occurrence with genes. Go along with the four typical phenotypes, PTK2 (with “adhesion”, freq = 64), CDH1 (with “migration”, freq = 49), MMP9 (with “invasion”, freq = 104) and VEGFA (with “angiogenesis”, freq = 98) were the most popular genes, respectively.

Figure 3. The co-occurrence between genes and metastasis-related phenotypes.

For each phenotype the size of circle indicated the number of genes that arise with it in one sentence. The thickness of edge reflected the frequency of each co-occurrence relationship.

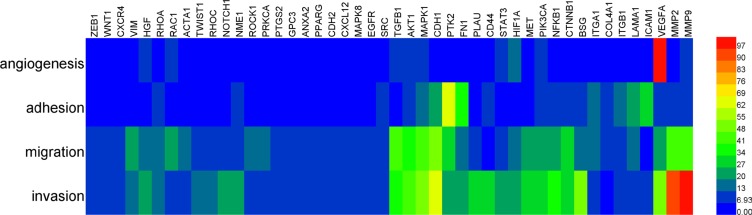

To highlight the genes that may affect multiple phenotypes, genes co-occurred with 2 or more phenotypes (threshold of frequency was 7) were listed and cluster analysis was performed in Figure 4. Several genes, such as VEGFA, PI3KCA, MAPK1 and MMP9, were obviously involved in almost all steps, and they should be preferentially regarded as potential regulators for HCC metastasis.

Figure 4. Cluster analysis for genes that co-appeared with metastasis-related phenotypes.

Data were linearly normalized. Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed based on maximum-linkage, using similarity metric of Euclidean distance.

DISCUSSION

As an effective method [10], text mining has been used to explore regulation mechanism for several types of cancers, including glioblastoma [11], endometrial cancer [12], prostate cancer [13, 14], and breast cancer [15]. Actually, the relationship between gene and cancer is specific: under specific environment, through specific pathways, and affect specific processes or phenotypes of tumor biology, such as transformation, proliferation, metastasis, recurrence, drug resistance and so on. To get more valuable information, the objective of text mining should be clearly defined. For our study, we focus on “HCC metastasis”, and the relationship between genes and different steps of metastasis were calculated respectively. With specific aim and multiple methods, the association between genes and HCC metastasis could be more precisely addressed.

The etiology of HCC is another crucial issue. As mentioned above, HBV and HCV infection have different mechanisms of tumorigenesis, so they may exert different approaches for HCC metastasis. Exploration for such etiology-specific pathways may shed promise for targeted drugs and personalized treatments.

As a matter of fact, the most popular genes are not always the most important ones. Meanwhile, some other genes though crucial for HCC metastasis, may not get due attention. The purpose of our paper is not just to gather what have been done by now, but also to reveal what should be focused in the future. Genes with moderate frequency, but involved in multi-processes or interacting with principal molecules, might be fertile land for novel discoveries.

Each method used in this research has its own advantages and disadvantages. Frequency calculation is an effective method for text mining, but not enough for functional analysis. PPI network analysis is useful to find out hub regulators, but the specificity may be impaired with too much inputs. Co-occurrence analysis with phenotypes or biological functions is an improvement of word frequency analysis, where the universality of information and the specificity of the results are simultaneously emphasized, but the feature words have to be identified in advance. So these methods should be carefully selected and results should be extensively considered.

There are still some limitations in this study. First, ABNER is a biomedical entity recognition software based on statistical machine learning [16]. Although it has been optimized, not all genes will be identified. Second, it takes a long time to check gene names, symbols and alias. Third, text mining can calculate the frequencies of specific words and calculate their relationships, but they cannot actually “understand” literatures. However, text mining is still helpful for us to observe molecular biology achievements of HCC metastasis on a macro level, and quantitatively assess the roles and relationships for genes with multidimensional perspectives.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We search PubMed with the statement (HCC OR “hepatocellular carcinoma”) AND metastasis, and 8218 literatures were found out (to June 15th, 2016). Similarly, “HBV AND (HCC OR “hepatocellular carcinoma”) AND metastasis” and “HCV AND (HCC OR “hepatocellular carcinoma”) AND metastasis” were applied to collect genes involved in HCC metastasis resulting from HBV or HCV. All abstracts were downloaded from PubMed document retrieval system. Genes and proteins among abstracts were identified with ABNER (Version 1.5) [16, 17]. Gene symbols were normalized manually based on the Entrez Gene Database. Word frequency analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel 2010. To reflect the relationship between genes and metastasis, several phenotypes were selected, such as “metastasis”, “adhesion”, “migration”, “invasion” and “angiogenesis”. Only the genes that co-appeared with these words in the same sentence will be counted. If a gene appeared several times in one sentence, it would be treated once. KEGG pathway analysis was performed on GATHER (Gene Annotation Tool to Help Explain Relationships, http://gather.genome.duke.edu/) [18], and the threshold of P is 0.05.

The protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was integrated with BisoGenet [19], and interaction data come from BIND [20, 21], BioGrid [22], DIP [23], MINT [24], IntAct [25] and HPRD [26]. All interactions were based on experiments. The PPI network was illustrated with Cytoscape (version 3.4.0) [27] and analyzed with CytoNCA [28], a plugin for Cytoscape. Co-occurrence analysis between genes and phenotypes was illustrated with Gephi (Version 0.8.2 beta) [29]. Hierarchical cluster analysis based on maximum-linkage (similarity metric with Euclidean distance) was performed with HemI (Version 1.0) [30].

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International journal of cancer. 2015;136:E359–386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Page AJ, Cosgrove DC, Philosophe B, Pawlik TM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: diagnosis, management, and prognosis. Surgical oncology clinics of North America. 2014;23:289–311. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang ZY. Hepatocellular carcinoma—cause, treatment and metastasis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2001;7:445–454. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i4.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sukowati CH, El-Khobar KE, Ie SI, Anfuso B, Muljono DH, Tiribelli C. Significance of hepatitis virus infection in the oncogenic initiation of hepatocellular carcinoma. World journal of gastroenterology. 2016;22:1497–1512. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i4.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ringelhan M, O'Connor T, Protzer U, Heikenwalder M. The direct and indirect roles of HBV in liver cancer: prospective markers for HCC screening and potential therapeutic targets. The Journal of pathology. 2015;235:355–367. doi: 10.1002/path.4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shirvani-Dastgerdi E, Schwartz RE, Ploss A. Hepatocarcinogenesis associated with hepatitis B, delta and C viruses. Current opinion in virology. 2016;20:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta GP, Massague J. Cancer metastasis: building a framework. Cell. 2006;127:679–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambers AF, Groom AC, MacDonald IC. Dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nature reviews Cancer. 2002;2:563–572. doi: 10.1038/nrc865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the 'seed and soil' hypothesis revisited. Nature reviews Cancer. 2003;3:453–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo Y, Riedlinger G, Szolovits P. Text mining in cancer gene and pathway prioritization. Cancer informatics. 2014;13:69–79. doi: 10.4137/CIN.S13874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Natarajan J, Berrar D, Dubitzky W, Hack C, Zhang Y, DeSesa C, Van Brocklyn JR, Bremer EG. Text mining of full-text journal articles combined with gene expression analysis reveals a relationship between sphingosine-1-phosphate and invasiveness of a glioblastoma cell line. BMC bioinformatics. 2006;7:373. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao H, Zhang Z. Systematic Analysis of Endometrial Cancer-Associated Hub Proteins Based on Text Mining. BioMed research international. 2015;2015:615825. doi: 10.1155/2015/615825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chun HW, Tsuruoka Y, Kim JD, Shiba R, Nagata N, Hishiki T, Tsujii J. Automatic recognition of topic-classified relations between prostate cancer and genes using MEDLINE abstracts. BMC bioinformatics. 2006;7:S4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-S3-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng X, Geng H, Bastola DR, Ali HH. Link test—A statistical method for finding prostate cancer biomarkers. Computational biology and chemistry. 2006;30:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krallinger M LF, Valencia A. Analysis of biological processes and diseases using text mining approaches. Methods Mol Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-194-3_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Settles B. ABNER: an open source tool for automatically tagging genes, proteins and other entity names in text. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3191–3192. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Settles B. Biomedical Named Entity Recognition Using Conditional Random Fields and Rich Feature Sets.; Proceedings of the International Joint Workshop on Natural Language Processing in Biomedicine and its Applications.; 2004; pp. 104–107.

- 18.Chang JT, Nevins JR. GATHER: a systems approach to interpreting genomic signatures. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2926–2933. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin A, Ochagavia ME, Rabasa LC, Miranda J, Fernandez-de-Cossio J, Bringas R. BisoGenet: a new tool for gene network building, visualization and analysis. BMC bioinformatics. 2010;11:91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bader GD, Betel D, Hogue CW. BIND: the Biomolecular Interaction Network Database. Nucleic acids research. 2003;31:248–250. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willis RC, Hogue CW. Searching, viewing, and visualizing data in the Biomolecular Interaction Network Database (BIND). Current protocols in bioinformatics / editoral board. Andreas D Baxevanis [et al] 2006:9. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0809s12. Chapter 8: Unit 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stark C, Breitkreutz BJ, Chatr-Aryamontri A, Boucher L, Oughtred R, Livstone MS, Nixon J, Van Auken K, Wang X, Shi X, Reguly T, Rust JM, Winter A, et al. The BioGRID Interaction Database 2011 update. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39:D698–704. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xenarios I, Salwinski L, Duan XJ, Higney P, Kim SM, Eisenberg D. DIP. the Database of Interacting Proteins: a research tool for studying cellular networks of protein interactions. Nucleic acids research. 2002;30:303–305. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Licata L, Briganti L, Peluso D, Perfetto L, Iannuccelli M, Galeota E, Sacco F, Palma A, Nardozza AP, Santonico E, Castagnoli L, Cesareni G. MINT. the molecular interaction database: 2012 update. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:D857–861. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aranda B, Achuthan P, Alam-Faruque Y, Armean I, Bridge A, Derow C, Feuermann M, Ghanbarian AT, Kerrien S, Khadake J, Kerssemakers J, Leroy C, Menden M, et al. The IntAct molecular interaction database in 2010. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:D525–531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goel R, Muthusamy B, Pandey A, Prasad TS. Human protein reference database and human proteinpedia as discovery resources for molecular biotechnology. Molecular biotechnology. 2011;48:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s12033-010-9336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome research. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang Y, Li M, Wang J, Pan Y, Wu FX. CytoNCA: a cytoscape plugin for centrality analysis and evaluation of protein interaction networks. Bio Systems. 2015;127:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bastian M HS, Jacomy M. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks.; The International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.; 2009..

- 30.Deng W, Wang Y, Liu Z, Cheng H, Xue Y. HemI: a toolkit for illustrating heatmaps. PloS one. 2014;9:e111988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]