Abstract

The World Health Organization recommends vaccination of pregnant women for seasonal influenza that can also protect infants aged below 6 months. We estimated incidence and disease burden of influenza in hospitalised children below and above 6 months of age in Hong Kong during a 6 year period. Discharge diagnoses for all admissions to public Hong Kong Hospital Authority hospitals, recorded in a central computerised database (Clinical Management System, CMS), were analysed for the period April 2005 to March 2011. Incidence estimates of influenza disease by age group were derived from CMS ICD codes 487–487.99. Laboratory-confirmed influenza infections from a single surveillance hospital were then linked to the CMS entries to assess possible over- and under-diagnosis of influenza based on CMS codes alone. Influenza was recorded as any primary or any secondary diagnosis in 1.3% (1158/86,582) of infants aged above 6 days to below 6 months and 4.3% (20,230/471,482) of children above 6 days to below 18 years. The unadjusted incidence rates per 100,000 person-years based on any CMS diagnosis of influenza in all admission to Hong Kong public hospitals were 627 in the below 2 months of age group and 1762 in the 2 month to below 6 month group. Incidence of hospitalisation for influenza in children was highest from 2 months to below 6 months. In the absence of vaccines for children below 6 months of age, effective vaccination of pregnant women may have a significant impact on reducing influenza hospitalisations in this age group.

Abbreviations: CMS, Clinical Management System; HA, Hospital Authority; ICD9-CM, International Classification of Diseases; NPA, nasopharyngeal aspirates; A(H1N1)pdm09, 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1NI) virus; PWH, Prince of Wales Hospital; WHO, World Health Organization

Keywords: Influenza, Disease burden, Infants, Children, Hospitalisation

1. Background

Influenza is a burden to the Hong Kong healthcare system and a significant cause for hospitalisation among the paediatric population. Discharge diagnoses for all admissions to publicly funded government (Hospital Authority, HA) hospitals in Hong Kong are recorded in a central computerised database (Clinical Management System, CMS) [1], [2]. A 2002 study using the CMS data showed hospitalisation rates in Hong Kong for influenza to be 3–10 times higher than those reported for children in the United States, equating to nearly 3% of children under 1 year old being hospitalised each year due to influenza [3]. An analysis of the CMS database for July 1997 through June 1999 for children aged less than 15 years reported a primary diagnosis of a respiratory disorder in 37.5% of general paediatric admissions [1]. CMS diagnosis incidence rates of influenza during this 2-year period were 222–381 per 100,000 children under 5 years and 415–528 per 100,000 children under the age of 1 year.

Following the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2003, infection control measures in Hong Kong hospitals were enhanced and many hospitals routinely collect nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPA) for all children with suspected respiratory infections. This situation has enabled us to analyse data collected routinely through the CMS system and combine this with enhanced laboratory surveillance activities from one hospital to make estimates of influenza disease burden in hospitalised children in Hong Kong. The current analysis compares data for infants aged below 6 months with children below 18 years over a 6-year period (April 2005–March 2011).

2. Methods

This study protocol was approved by the Joint The Chinese University of Hong Kong and New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

2.1. CMS data

Information collected by the CMS includes patient identifiers, date of birth, sex, a maximum of 15 diagnoses and 15 procedures (classified by International Classification of Diseases ICD9 and ICD9-CM codes), and admission and discharge dates [1]. The CMS was rolled out from 1996, and by mid-1997 this information was available for all HA hospitals. Prior to 2000, the majority of HA hospitals only coded the primary diagnosis for most hospital admissions. A database of all paediatric patients admitted to general paediatric and neonatal wards from 1 April 2005 to 31 March 2011 was provided by the HA. Respiratory-associated admissions for children aged above 6 days to below 6 months and above 6 days to below 18 years were assessed by these ICD diagnostic groups and by hospital of admission, outcome status (died, discharged home with or without follow-up and transferred to another hospital) and severity as measured by the length of stay. Infants below 7 days of age were excluded from these initial analyses as the large majority of these infants were admitted during the immediate post-partum period due perinatal and neonatal problems.

2.2. Laboratory methods for influenza diagnosis at Prince of Wales Hospital

Since 2003 NPA are collected for all children with suspected respiratory infections at PWH as a standard procedure as part of routine care. At PWH during the periods March 2005 to March 2006 [4], and October 2008 to March 2011 enhanced diagnostics were available to document additional viral and bacterial pathogens. All specimens are subjected to respiratory virus detection by the immunofluorescence (IF) test and/or conventional virus culture as described previously [5].

2.3. Linking of CMS with laboratory data for Prince of Wales Hospital

Laboratory data for all paediatric admissions from PWH were matched on the unique hospital number with the CMS data. Age-related analyses were based on the CMS calculated dayage (date of admission minus date of birth in days) and monthage (dayage divided by 30.4). The laboratory dataset used for analysis only included a single hospital number and a single laboratory request number i.e. a single entry with a positive result was chosen if more than two NPA specimens were sent during the admission.

2.4. Calculation of influenza hospitalisation incidence rates by age group from CMS discharge diagnosis

Incidence rates of hospitalisation for influenza for all HA hospitals in Hong Kong were first estimated from the total number of children with any CMS diagnosis of influenza (ICD-CM 487–487.9) (CMS flu+). Infants below 7 days of age were included in this incidence analysis. These initial unadjusted CMS flu incidence rates for each year by age were calculated with the following formula:

where x is the number of admissions by age with any CMS influenza diagnosis (ICD-CM 487–487.9) and y is the admissions to public HA hospitals as a percentage of total admissions by age (Appendix 1).

These proportions were weighted by the number of admissions when incidence estimates were calculated for different age groups:

where Admissionsj is the number of admissions in the jth age group, and P j is the proportion of admissions to HA hospitals in the jth age group; z is the estimated resident population by age (Appendix 2).

Incidence rates were calculated by monthly age groups and then re-grouped according to different age ranges (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Any influenza diagnosis reported from Clinical Management System (CMS) compared with actual results from the virology laboratory of the Prince of Wales Hospital for all patients aged below 18 years who had specimens sent for testing (1 April 2005 to 31 March 2011).

| Year | Total admissions | LAB flu+/CMS flu+a | LAB flu+/CMS flu−a | LAB flu−/CMS flu+a | Primary respiratoryb | Primary respiratoryb NPAc NOT sent | AF1 d calculated | AF1 d mean value used | AF2e calculated | AF2e mean value used | AF3f calculated value weighted by age group | AF3f smoothed value weighted by age group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to <2m | 19,883 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 267 | 124 | 1.14 | 1.05 | 1.48 | 1.13 | 0.0008 | – |

| 2 to <6m | 3211 | 110 | 9 | 6 | 813 | 47 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.13 | 0.0371 | 0.0351 |

| 6m to <1y | 4000 | 131 | 23 | 20 | 1228 | 129 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 1.07 | 1.13 | 0.0385 | 0.0427 |

| 1 to <2y | 5221 | 266 | 40 | 42 | 1728 | 284 | 0.99 | 1.05 | 1.09 | 1.13 | 0.0586 | 0.0552 |

| 2 to <5y | 10,000 | 611 | 128 | 67 | 3465 | 354 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.16 | 1.13 | 0.0739 | 0.0739 |

| 5 to <10y | 7604 | 568 | 104 | 62 | 2294 | 308 | 1.07 | 1.05 | 1.18 | 1.13 | 0.0884 | 0.0880 |

| 10 to 14y | 4987 | 205 | 27 | 22 | 824 | 120 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 0.0465 | 0.0474 |

| 14 to <18y | 5031 | 93 | 21 | 29 | 444 | 124 | 0.93 | 1.05 | 1.12 | 1.13 | 0.0227 | 0.0230 |

| <5y | 42,315 | 1127 | 207 | 140 | 7501 | 938 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 0.0315 | 0.0348 |

| Total | 59,937 | 1993 | 359 | 253 | 11,063 | 1490 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 0.0392 | 0.0422 |

LAB flu+ = laboratory test positive for influenza (Influenza A and B); LAB flu− = laboratory test negative for influenza (Influenza A and B); CMS flu+ = Clinical Management System diagnosis of influenza (ICD = 487–487.99); CMS flu− = Clinical Management System diagnosis NOT influenza (not ICD = 487–487.99).

Primary respiratory = Clinical Management System diagnosis reports a primary respiratory-associated diagnosis (upper respiratory infection [460–461.9, 465–465.9, 786.2]; tonsillitis/pharyngitis [462–463.9, 034.0, 474.11]; croup/laryngitis [464–464.9, 786.1]; acute otitis media [381–382.9]; bronchitis/chest infection [466–466.09, 490–490.9, 519.8]; bronchiolitis [466.1–466.9]; pneumonia [480–486.9, 507.0]; influenza [487–487.9]; asthma/allergic rhinitis [493–493.9, 477–477.9]).

NPA: nasopharyngeal aspirate.

Adjustment factor 1 = LAB flu+/CMS flu+.

Adjustment factor 2 = [LAB flu+] + [primary respiratory associated diagnosis and NPA NOT sent * (LAB flu+/NPA sent)]/CMS flu+.

Adjustment factor 3 = LAB flu+/total admissions by age group.

2.5. Calculation of adjustment factors

Since a CMS flu diagnosis may reflect both under- and over-diagnosis, we applied adjustment factors to this CMS Flu derived incidence estimate (Table 1). These factors were derived by linking the PWH laboratory surveillance data (LAB flu+ or LAB flu−) with the PWH CMS data (CMS flu+ or CMS flu−) (Appendix 3). The first factor was derived to adjust for potential under-reporting of influenza infection by the CMS system. The second factor was derived to reflect the potential under-estimation of a PWH laboratory diagnosis of influenza by accounting for the fact that not all admissions with a primary respiratory-associated diagnosis had a NPA specimen sent to the laboratory for testing. The third factor was the proportion of all admissions to PWH by age group that had a laboratory confirmed diagnosis of influenza. No assessment or adjustment was made for possible nosocomial infections.

3. Results

3.1. CMS diagnoses by age group for all HA hospitals

During the 6-year study period 1 April 2005 to 31 March 2011, there were 624,916 children admitted to the paediatric medical wards of all HA hospitals; 2 had no gender specified and 86 had missing age data and were excluded. Of the 624,828 children with valid data, 94.5% (590,683) were below the age of 18 years and 32.9% (205,783) were below the age of 6 months, 13.9% (86,582) were aged above 6 days to below 6 months (6M group) and 75.5% (471,482) were aged above 6 days to below 18 years (18Y group). In the 6M and 18Y groups respiratory-associated disorders were respectively coded as the primary diagnosis in 13.9% and 27.2% of admissions, and as the primary or as one of any 9 secondary diagnoses in 15.7% and 31.8% (Appendix 4).

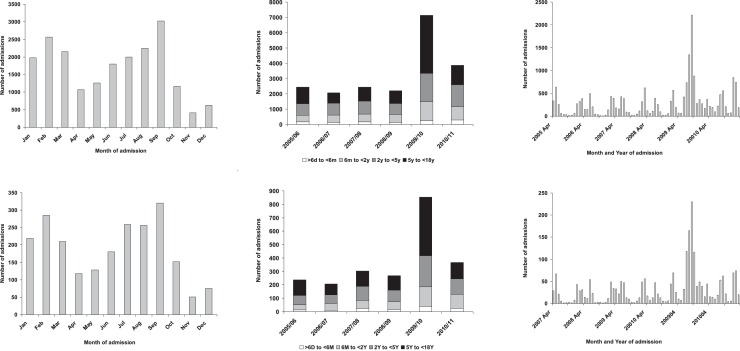

The percentage of all discharges with a primary diagnosis and “any” diagnosis of influenza (CMS flu) ranged from 0.3% to 1.4% and 0.4 to 1.9% in the 6M group and from 0.9% to 4.2% and 1.3% to 6.0% in the 18Y group respectively in the 12 HA hospitals (Appendix 5). Likewise rates of admissions coded as having a respiratory illness varied considerably between these different hospitals. Influenza admissions peaked during February and September (Fig. 1 ). Over the full 6 year study period there was a peak of admissions during the April 2009–March 2010 (Fig. 1). A similar pattern was seen with the data from all HA hospitals and with data from PWH alone (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Seasonality of admissions with a discharge diagnosis of influenza (ICD9-CM 487–487.9) for all Hospital Authority Hospitals (top row) and for Prince of Wales Hospital (bottom row).

3.2. Linking laboratory influenza diagnosis to CMS diagnoses at Prince of Wales Hospital

After linking the CMS data to the laboratory surveillance data at PWH, there were 8325 admissions in the 6M group and 45,168 in the 18Y group that could be matched on their hospital number (Appendix 6). There were 18,002 records in the laboratory database of which 17,783 could be matched with the hospital number to the CMS data and included in the analysis. The remaining 219 records were either not within the age range or could not be matched with their hospital number. In the 6M and 18Y groups, NPAs were requested on 2066 (24.8%) and 17,783 (39.4%) admissions (Appendix 7) and were positive in 6.5% (range 4.8–9.9%) and 13.2% (range 9.2–21.5%) during the 6 year period respectively (Appendix 8). Overall 1.6% of admissions in the 6M group and 5.2% in the 18Y group had a positive NPA for influenza (Appendix 7). In both age groups the highest positivity rate was in the 2009/10 period during which time the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1NI) virus (A(H1N1)pdm09) influenza strain circulated but this effect was less marked in the 6M group (Appendix 8). In all HA hospitals the proportion of all admissions, and the proportion of admissions to general wards and intensive care units, that had a CMS diagnosis of influenza was almost double during the 2009/10 period (Appendix 9).

3.3. Calculation of adjustment factors

Including all children from 0 days to below 18 years, 1993 had both a laboratory positive result and CMS diagnosis (ICD9-CM 487–487.9) of influenza (Table 1). There were an additional 359 children without a CMS diagnosis of influenza but with a laboratory confirmed result, and 253 with a CMS diagnosis of influenza but without laboratory confirmation. This indicates that a CMS diagnosis of influenza under-estimates disease burden relative to the laboratory results despite wide and routine laboratory testing with NPAs in children with fever or respiratory illnesses. Since there appeared to be no obvious age effect (Appendix 3) an overall mean value of 1.05 was used for adjustment factor 1 for all age groups. Of the 11,063 children with a primary-respiratory associated diagnosis, 1490 did not have an NPA sent. Adjustment factor 2 assumed the influenza positive rate in these 1490 children was the same as in the 9573 children that had an NPA sent (Table 1). Again this factor did not appear to vary consistently with age and overall mean value of 1.13 was applied to all age groups (Appendix 3). Adjustment factor 3 was the proportion of all admissions by age group that had a laboratory diagnosis of influenza at PWH (Table 1). This factor varied by age group and a smoothed value excluding the first two months was applied to each monthly age group for the complete HA dataset (Appendix 3).

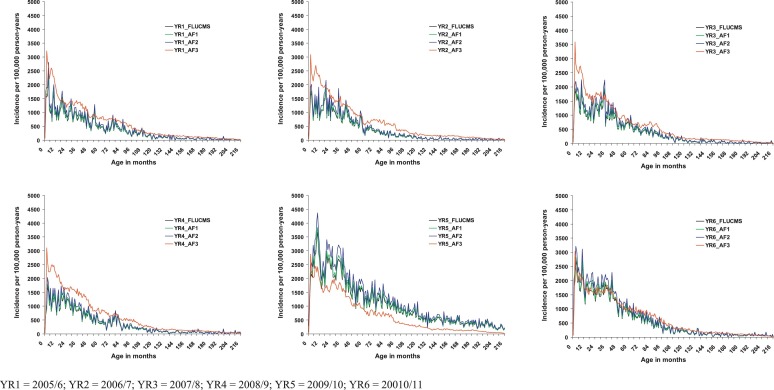

3.4. Unadjusted and adjusted influenza incidence estimates for Hong Kong

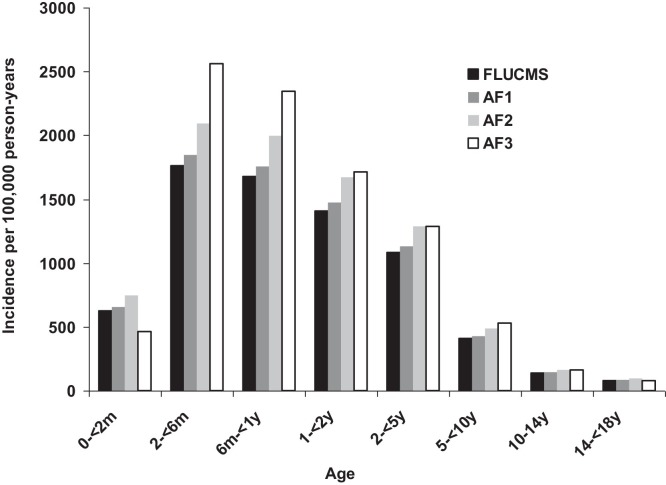

The incidence rates of hospitalisation for influenza per 100,000 person-years based on any CMS influenza diagnosis (CMS flu) for the whole of Hong Kong were lowest in the first two months of life, then peaked between 2 and 6 months, and then declined from about 3 to 4 years of age (Fig. 2, Fig. 3 ). Similar patterns were observed over the full 6 years of the study. The unadjusted incidence rates per 100,000 person-years based on any CMS diagnosis of influenza in all admission to Hong Kong public hospitals were 627 in the below 2 months of age group; 1762 in the 2 month to below 6 month group; 1677 in the 6 month to below 1 year group; 1408 in the 1 to below 2 years group; 1081 in the 2 to below 5 years group; 409 in the 5 to below 10 years group; and 137 in the 10 to below 14 years group; and 81 in the 14 to below 18 years group (Table 2 ). Incidence rates were highest in the A(H1N1)pdm09 year (April 2009 to March 2010) (Table 2, Fig. 2). Adjusted incidence rates were generally in a similar range to the unadjusted rates with the exception of those rates estimated using adjustment factor 3 – in most years this estimate was higher than the other estimates, whereas in the A(H1N1)pdm09 year it was lower (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Incidence of hospitalised influenza by age (0 to below 18 years) and admission year, Hong Kong (1 April 2005 to 31 March 2011).

Fig. 3.

Incidence of hospitalised influenza (ICD9-CM 487–487.9) by age group with and without application of adjustment factors derived from laboratory surveillance at one hospital, Hong Kong (1 April 2005 to 31 March 2011).

Table 2.

Incidence rates for hospitalisation with influenza per 100,000 person-years in Hong Kong (1 April 2005 to 31 March 2011).

| All years | 2005/6 | 2006/7 | 2007/8 | 2008/9 | 2009/10 | 2010/11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates based on ANY CMS diagnosis of influenza (ICD9-CM 487–487.9) with no adjustment | |||||||

| 0 to <2m | 627 | 796 | 469 | 509 | 367 | 714 | 887 |

| 2 to <6m | 1762 | 1665 | 1306 | 1700 | 1286 | 2235 | 2286 |

| 6m to <1y | 1677 | 1134 | 1190 | 1380 | 1184 | 3034 | 1961 |

| 1 to <2y | 1408 | 1025 | 1154 | 1017 | 1098 | 2290 | 1661 |

| 2 to <5y | 1081 | 739 | 807 | 926 | 757 | 1901 | 1343 |

| 5 to <10y | 409 | 310 | 211 | 314 | 264 | 984 | 452 |

| 10 to 14y | 137 | 78 | 46 | 61 | 67 | 486 | 114 |

| 14 to <18y | 81 | 37 | 24 | 23 | 41 | 301 | 66 |

| <5y | 1295 | 924 | 976 | 1075 | 934 | 2188 | 1591 |

| Estimates based on ANY CMS diagnosis of influenza (ICD9-CM 487–487.9) with adjustment for under- and over-CMS flu diagnosis based on data from Prince of Wales Hospital (factor 1)a | |||||||

| 0 to <2m | 656 | 834 | 491 | 533 | 385 | 748 | 929 |

| 2 to <6m | 1845 | 1744 | 1367 | 1781 | 1346 | 2340 | 2394 |

| 6m to <1y | 1756 | 1188 | 1247 | 1446 | 1239 | 3177 | 2054 |

| 1 to <2y | 1475 | 1073 | 1209 | 1065 | 1150 | 2398 | 1739 |

| 2 to <5y | 1133 | 773 | 845 | 969 | 792 | 1990 | 1407 |

| 5 to <10y | 428 | 325 | 221 | 329 | 276 | 1030 | 473 |

| 10 to 14y | 144 | 81 | 48 | 64 | 70 | 509 | 120 |

| 14 to <18y | 85 | 39 | 25 | 24 | 43 | 315 | 69 |

| <5y | 1356 | 968 | 1022 | 1125 | 978 | 2292 | 1667 |

| Estimates based on ANY CMS diagnosis of influenza (ICD9-CM 487–487.9) with adjustment for under- and over-CMS flu diagnosis and failure to send NPA on all respiratory-related admissions based on data from Prince of Wales Hospital (factor 2)a | |||||||

| 0 to <2m | 745 | 947 | 557 | 605 | 437 | 849 | 1054 |

| 2 to <6m | 2093 | 1979 | 1552 | 2021 | 1528 | 2655 | 2716 |

| 6m to <1y | 1993 | 1348 | 1415 | 1640 | 1407 | 3605 | 2330 |

| 1 to <2y | 1673 | 1218 | 1372 | 1208 | 1305 | 2721 | 1974 |

| 2 to <5y | 1285 | 878 | 958 | 1100 | 899 | 2259 | 1597 |

| 5 to <10y | 486 | 369 | 251 | 374 | 313 | 1169 | 537 |

| 10 to 14y | 163 | 92 | 54 | 73 | 80 | 577 | 136 |

| 14 to <18y | 97 | 44 | 28 | 27 | 49 | 358 | 78 |

| <5y | 1539 | 1099 | 1159 | 1277 | 1110 | 2601 | 1891 |

| Estimates based on assumption that laboratory confirmed influenza admissions as a proportion of all admissions by age group identified in Prince of Wales Hospital (active surveillance) is the same proportion of all admission to all HA hospitals (factor 3)a | |||||||

| 0 to <2m | 1493 | 1580 | 1323 | 1438 | 1365 | 1540 | 1695 |

| 2 to <6m | 2587 | 2757 | 2518 | 2914 | 2582 | 2375 | 2444 |

| 6m to <1y | 2354 | 2392 | 2466 | 2533 | 2406 | 2275 | 2105 |

| 1 to <2y | 1737 | 1532 | 1975 | 1715 | 1898 | 1675 | 1661 |

| 2 to <5y | 1310 | 1128 | 1218 | 1295 | 1331 | 1435 | 1448 |

| 5 to <10y | 521 | 513 | 481 | 483 | 501 | 539 | 630 |

| 10 to 14y | 162 | 160 | 165 | 150 | 145 | 177 | 183 |

| 14 to <18y | 77 | 72 | 74 | 70 | 75 | 86 | 84 |

| <5y | 2906 | 2670 | 2781 | 2871 | 2957 | 3018 | 3107 |

See text for description of three adjustment factors.

3.5. Length of stay and outcome

The median hospital stay for a CMS diagnosis of influenza was 2 days (interquartile range 1.3) in both 6M and 18Y groups (Appendix 10). This was less than for those children coded as having lower respiratory infections (bronchitis, chest infection, bronchiolitis and pneumonia). Eleven of 549 recorded deaths had a CMS diagnosis of influenza, but in only two children was this recorded as the primary diagnosis and none of these were in the 6M group (Appendix 11). Children with influenza were more likely to be discharged home without follow-up. This pattern was similar to those children with other respiratory-associated diagnoses but overall children were more commonly discharged with follow-up.

The median length of stay for the laboratory confirmed influenza admissions at PWH were also 2 days (interquartile range 1.3 days) for most of the study years and for most of the influenza types (Appendix 12). However by categorising length of stay into three groups (<2 days, 2 days, >2 days), there were significant differences between the different influenza types with more children admitted with influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 having stays of less than 2 days and more children with influenza B having longer stays (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Laboratory confirmed influenza cases associated with length of hospital stay, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong from 1 April 2005 to 31 March 2011.

| Total | <2 days | 2 days | >2 days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3N2 | 601 | 219 (36.4%) | 206 (34.3%) | 176 (29.3%) |

| H1N1 | 316 | 102 (32.3%) | 104 (32.9%) | 110 (34.8%) |

| pH1N1a | 696 | 300 (43.1%) | 186 (26.7%) | 210 (30.1%) |

| NDb | 222 | 77 (34.7%) | 77 (34.7%) | 68 (30.1%) |

| Influenza B | 517 | 168 (32.5%) | 129 (25.0%) | 220 (42.6%) |

The p-value of Pearson Chi squared test is <0.001.

2009 pandemic influenza (H1N1) virus (A(H1N1)pdm09)

Not determined: subtype not available, as influenza A was confirmed only by antigen detection by IF or DNA detection by RT-PCR of M gene of influenza A.

4. Discussion

In the recent recommendations issued by the World Health Organization for seasonal influenza vaccines [6], pregnant women were listed as the highest priority with the view that maternal immunisation will offer protection for children below 6 months of age since there are currently no vaccines licensed for this age group. Our study aimed to assess the disease burden of influenza-associated hospitalisation for young infants below 6 months of age in Hong Kong. Our results indicated that the unadjusted incidence rates per 100,000 person-years based on any CMS diagnosis of influenza hospitalisation (CMS flu) for all admissions to HA hospitals in Hong Kong were 627 in the below 2 months age group and peaked at 1762 in the 2 months to below 6 months age group. We previously reported incidence rates per 100,000 for the period 1997–1998 that were substantially less than our current estimates (Table 4 ) [1], possibly reflecting that NPAs were not routinely requested for all respiratory-associated admissions prior to the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2003. It is also likely that the overall incidence rates in our current study have been inflated by the increased numbers of influenza admissions during the A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic period during 2009/10. Our current rates are also higher than those of another recent Hong Kong study [7], but lower than those of an earlier report by the same group (Table 4) [3]. However, the burden of disease alters in relation to both the vaccine coverage in these children and the protection elicited by the vaccines that covered the circulating virus strain types of the respective seasons. We were unable to differentiate between cases infected with vaccine-covered or non-vaccine-covered strains as not all patients had their virus isolates characterised. However, based on the data provided by the National Influenza Reference Laboratory (personal communications), the trivalent vaccine strains matched with our circulating strains in 2005 and 2010; and incomplete match occurred with influenza A H3 strains for 2006 and 2011. For 2007 and 2009, the influenza A H1N1 strains were not matched while influenza B strains were not matched in 2008. However, data suggested the uptake rate among infants 6–23 months was low at 8.5% during the 2005/6 flu season [8], but the introduction of governmental subsidies to influenza vaccination for aged 6–59 months since 2008 may have improved vaccine uptake.

Table 4.

Comparative hospitalised influenza incidence estimates per 100,000 person-years by age by study period, Hong Kong.

| Study period | 0–2m | 2 to <6m | 6m to <1y | 1–2y | 2 to <5y | 5 to <10y | 10 to <14y | 14 to <18y | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMS Flu | Apr 2005–Mar 2011 | 627 | 1762 | 1677 | 1408 | 1081 | 409 | 137 | 81 | Current study |

| CMS Flu adjusted by factor 1 | Apr 2005–Mar 2011 | 656 | 1845 | 1756 | 1475 | 1133 | 428 | 144 | 85 | Current study |

| CMS Flu adjusted by factor 2 | Apr 2005–Mar 2011 | 745 | 2093 | 1993 | 1673 | 1285 | 486 | 163 | 97 | Current study |

| CMS Flu adjusted by factor 3 | Apr 2005–Mar 2011 | 1493 | 2587 | 2354 | 1737 | 1310 | 521 | 162 | 77 | Current study |

| Oct 2003–Sep 2006 | 389–1038 | 409–955 | 381–595 | 109–219 | 15–29 (10 to <15y) | 24–48 (15 to <18y) | [7] | |||

| Jan 1997–Dec 1999 | 2785–2882 | 2093–2184 | 773–1256 | 209–573 | 81–164 (10 to <16y) | – | [3] | |||

| Jul 1997–Jun 1999 | 415–528 | [1] | ||||||||

| Jul 1997–Jun 1999 | 222–381 | [1] | ||||||||

Pregnant women are a high risk group that can benefit from seasonal influenza vaccination and recent studies have suggested that their infants will also enjoy some degree of protection [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16].

The vaccination uptake rate among pregnant women in Hong Kong is low in general, and ranged between 1.7 and 4.9% from various studies reported during this period [17], [18], [19]. Should a vaccination programme targeting pregnant women also reduce the high influenza incidence of hospitalisation in infants aged 2 months to below 6 months, it is likely that vaccine uptake would increase and cost-effectiveness of the programme would be enhanced.

In contrast to high influenza hospitalisation rate in infants aged 2 months to below 6 months was the low rate in infants below two months of age (627 per 100,000). This low rate was despite the high absolute numbers of infants admitted during the first two months of life (Table 1). A US study has shown that infants below 3 months of age are more likely to present with fever alone than children aged 3 months to below 24 months of age, and although they generally do well and have a shorter duration of hospital stay, they are more likely to be admitted [20].

This analysis shows the potential of combining laboratory surveillance and passive discharge diagnosis surveillance to monitor disease burden of vaccine-preventable pathogens [1], [2]. Using laboratory surveillance from one or more sentinel sites, it is possible to monitor disease coding and revise estimates of disease burden based on discharge diagnoses. However even with a practice of routine NPA testing for respiratory related illness, not all children will have specimens collected for laboratory confirmation. In our analysis we have made estimates of possible increased disease burden had all children had specimens taken. The laboratory surveillance at PWH suggested that up to 1.6% of infants aged above 6 days and below 6 months of age and 5.2% of children aged above 6 days to below 18 years are admitted to hospital as a result of influenza infection. We adjusted the CMS flu diagnosis estimates using factors derived from linking our laboratory surveillance results at PWH to the CMS coded diagnoses and then extrapolated these adjustments to the whole of Hong Kong. These adjusted rates were generally higher than the unadjusted rates (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). During the A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic in 2009/10 the proportion of children aged above 6 days to below 18 years admitted to hospital who had a diagnosis of influenza almost doubled (9.8%). Reasons for this increase incidence during 2009/2010 could reflect a genuine increase in disease burden or alternatively it could reflect changes in admission policy e.g. all suspected A(H1N1)pdm09 infections, including mild cases, were recommended for admission. Measures for severity of illness in the current study were length of stay, intensive care unit admission and outcome. Severity of influenza as measured by mortality and length of stay did not appear to be greater in the 6M group as compared to the 18Y group. The median length of stay for the A(H1N1)pdm09 admissions was similar to the that of the non-A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza admissions (Appendix 12) but when categorised into groups, a greater proportion of children with A(H1N1)pdm09 had a length of stay less than 2 days (Table 3), possibly reflecting less severe disease or a greater proportion of admissions with mild disease. However the number of intensive care unit admissions with any CMS diagnosis of influenza was highest during 2009/10. Incidence estimates based on adjustment factor 3 (PWH laboratory confirmed influenza rate) tended to be higher than the other incidence estimates except during 2009/10 (Fig. 2), possibly reflecting a sustained high level of routine NPA testing for influenza during the whole study period at PWH, but with other HA hospitals only increasing their NPA testing for influenza from 2009/10.

Limitations to our incidence estimates include a number of assumptions related to admissions to public HA hospitals and the resident Hong Kong population. The proportion of admissions to public hospitals has fallen in recent years and there has been a marked increase in the number of mothers from mainland China delivering in Hong Kong. It is possible that as a result of these social trends our incidence estimates (Table 2) are likely to be under-estimates rather than over-estimates since they exclude influenza admissions to hospitals in mainland China. Conversely our adjustment for under-testing (adjustment factor 2) could over-estimate true incidence since it is possible that children who are not tested represent a different clinical spectrum of disease, making invalid the assumption that the proportion of influenza positive cases in the untested group is the same as in the tested group. We also did not make any adjustments for children readmitted to the same or different HA hospital with the same influenza infection and for possible nosocomial infections which could have led to an over-estimation of incidence. It is also likely that children with nosocomial influenza will have a longer length of stay, emphasising that length of stay does not consistently reflect disease severity. We have also assumed that the adjustment factors derived from one institution, PWH, can be applied uniformly across all the HA hospitals, and that these factors are stable over time. Although PWH is one of the largest HA hospitals accounting for about 10% of all the public hospital paediatric admissions, it is possible that there may be differences in clinical practices, admission policies and laboratory services between PWH and other HA hospitals and also over time.

5. Conclusion

Estimates of the incidence of influenza that requires hospital admission were higher in children less than 5 years of age. Incidence per 100,000 person-years was particularly high for infants aged 2 months to below 6 months of age (1762) but lower in those below two months of age (627). Overall these estimates are higher than our previous 1997–1998 estimates but similar to other Hong Kong estimates. Although a higher positivity rate for influenza was noted during the 2009/10 influenza surveillance period when A(H1N1)pdm09 started to circulate, this could reflect a permissive admission policy rather than increased disease burden and/or severity. Our data support the recommendation that effective vaccination of pregnant women is likely to have a significant impact on reducing disease burden in young infants below 6 months of age hospitalised for influenza.

Acknowledgements

The Statistics and Workforce Planning Department in the Strategy and Planning Division of the Hong Kong Hospital Authority provided the paediatric hospitals admission dataset from the HA clinical data repository for this study.

Contributors: All authors approved the manuscript. E.A.S.N., M.I., J.S.T., A.W.M., P.K.S.C., contributed to study design and data interpretation. M.I. was the principal investigator. L.A.S. undertook literature review and initial drafting of manuscript. E.A.S.N., S.L.C., M.I., S.K.L., W.G., contributed to data analysis and interpretation. E.A.S.N. wrote the manuscript and produced all figures.

Funding: This study was funded by the World Health Organization as part of Project 49 of the United States of America Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Grant 5U50C1000748. The funding source played no role in the study design, data analysis or data interpretation. The research team had sole responsibility for all decisions about the conduct of the research and analysis of the findings.

Competing interests: E.A.S.N. has participated in vaccine studies funded by Baxter, GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune and Wyeth, has received funding to conduct disease surveillance studies from Merck and Pfizer, and lecture fees and travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Intercell and Pfizer. M.I. has received funding and support from Pfizer for respiratory disease surveillance studies. P.K.S.C. has participated in vaccine studies funded by Baxter, GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune and Wyeth, and has received lecture fees and travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck and Roche. The other authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Footnotes

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication, which does not necessarily reflect the views of the World Health Organization.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.063.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Nelson E.A., Tam J.S., Yu L.M., Li A.M., Chan P.K., Sung R.Y. Assessing disease burden of respiratory disorders in Hong Kong children with hospital discharge data and linked laboratory data. Hong Kong Med J. 2007;13(April (2)):114–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson E.A.S. In: Handbook of disease burdens and quality of life measures. Preedy V.R., Watson R.R., editors. Springer; New York: 2010. Disease burden of diarrhoeal and respiratory disorders in childr Hong Kong perspectives. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiu S.S., Lau Y.L., Chan K.H., Wong W.H.S., Peiris J.S.M. Influenza-related hospitalizations among children in Hong Kong. New Engl J Med. 2002;347(26):2097–2103. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ip M., Nelson E.A., Cheuk E.S., Sung R.Y., Li A., Ma H., et al. Serotype distribution and antimicrobial susceptibilities of nasopharyngeal isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae from children hospitalized for acute respiratory illnesses in Hong Kong. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(June (6)):1969–1971. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00620-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng P.K.C., Wong K.K.Y., Mak G.C., Wong A.H., Ng A.Y.Y., Chow S.Y.K., et al. Performance of laboratory diagnostics for the detection of influenza A(H1N1)v virus as correlated with the time after symptom onset and viral load. J Clin Virol. 2010;47(2):182–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper – November 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;87(47):461–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiu S.S., Chan K.H., Chen H., Young B.W., Lim W., Wong W.H.S., et al. Virologically confirmed population-based burden of hospitalization caused by influenza A and B among children in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(7):1016–1021. doi: 10.1086/605570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau J.T.F., Mo P.K.H., Cai Y.S., Tsui H.Y., Choi K.C. Coverage and parental perceptions of influenza vaccination among parents of children aged 6 to 23 months in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1026. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Legge A., Dodds L., MacDonald N.E., Scott J., McNeil S. Rates and determinants of seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnancy and association with neonatal outcomes. Can Med Assoc J. 2014;186(4):E157–E164. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.130499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchard-Rohner G., Meier S., Bel M., Combescure C., Othenin-Girard V., Swali R.A., et al. Influenza vaccination given at least 2 weeks before delivery to pregnant women facilitates transmission of seroprotective influenza-specific antibodies to the newborn. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(12):1374–1380. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000437066.40840.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eick A.A., Uyeki T.M., Klimov A., Hall H., Reid R., Santosham M., et al. Maternal influenza vaccination and effect on influenza virus infection in young infants. Arch Pediat Adol Med. 2011;165(2):104–111. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poehling K.A., Szilagyi P.G., Staat M.A., Snively B.M., Payne D.C., Bridges C.B., et al. Impact of maternal immunization on influenza hospitalizations in infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6 (Suppl. 1)):S141–S148. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Omer S.B., Goodman D., Steinhoff M.C., Rochat R., Klugman K.P., Stoll B.J., et al. Maternal influenza immunization and reduced likelihood of prematurity and small for gestational age births: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2011;8(5):e441–e1000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benowitz I., Esposito D.B., Gracey K.D., Shapiro E.D., Vazquez M. Influenza vaccine given to pregnant women reduces hospitalization due to influenza in their infants. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(12):1355–1361. doi: 10.1086/657309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinhoff M.C., Omer S.B., Roy E., Arifeen S.E., Raqib R., Altaye M., et al. Influenza immunization in pregnancy—antibody responses in mothers and infants. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1644–1646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0912599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaman K., Roy E., Arifeen S.E., Rahman M., Raqib R., Wilson E., et al. Effectiveness of maternal influenza immunization in mothers and infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1555–1564. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarrant M., Wu K.M., Yuen C.Y.S., Cheung K.L., Chan V.H.S. Determinants of 2009 A/H1N1 influenza vaccination among pregnant women in Hong Kong. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(1):23–32. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0943-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuen C.Y.S., Fong D.Y.T., Lee I.L.Y., Chu S., Siu E.S.M., Tarrant M. Prevalence and predictors of maternal seasonal influenza vaccination in Hong Kong. Vaccine. 2013;31:5281–5288. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau J.T.F., Cai Y., Tsui H.Y., Choi K.C. Prevalence of influenza vaccination and associated factors among pregnant women in Hong Kong. Vaccine. 2010;28(33):5389–5397. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bender J.M., Ampofo K., Gesteland P., Sheng X., Korgenski K., Raines B., et al. Influenza virus infection in infants less than three months of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(1):6–9. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181b4b950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.