Abstract

Objective: To determine the rate, type, and severity of dental injuries recorded for intermediate and high school interscholastic athletic participants.

Design and Setting: A longitudinal study (1988–2003) of intermediate and high school athletes utilizing the same certified athletic trainers to evaluate and record all injury data.

Subjects: Sports participation included 123 teams in 19 female, 18 male, and 2 coed sports. Of 2445 Punahou School intermediate and high school students, on average, 1340 students (623 females, 717 males) annually participated in interscholastic athletics.

Measurements: Dental injuries were defined as injuries to the jaw, teeth, and oral soft tissue (lip, mouth, cheek, and tongue). Soft tissue injuries requiring physician or dentist referral were recorded. Other soft tissue injuries were treated as skin abrasions and were not recorded. Actual days lost from activity were recorded. The estimated injury rate was determined (injuries/1000 athlete-sessions). Mouth-guard use was recorded.

Results: During the 15-year study, 19 492 injuries were reported, with 56 (0.2%) recorded as dental injuries (23 tooth, 20 jaw, and 13 soft tissue). Injury rates were highest for girls' wrestling (0.243, confidence interval = 0–2.3), boys' judo (0.189, confidence interval = 0–3.6), and boys' soccer (0.127, confidence interval = 0.4–1.4). The football injury rate was 0.029 (confidence interval = 0.04–0.29), with no tooth injuries.

Conclusions: The incidence and injury rate of dental injuries was extremely low for all reported sports. A universal definition of dental injuries must be established to facilitate injury data collection and analysis.

Keywords: athletic injuries, injury epidemiology, high school athletes

The dental injury rate in athletes, the effectiveness of mouth guards in injury reduction, the types of mouth guards that should be used by athletes, and the effectiveness of mouth guards in reducing or preventing concussion are topics of considerable interest to the dental and athletic communities. This report will focus on a 15-year study of the incidence of dental injury to intermediate and high school athletes participating in interscholastic athletic programs.

The lack of a universally accepted definition of dental injury creates difficulties with regard to data collection, analysis, and reporting. Tesini and Soporowski1 noted the inconsistency of diagnostic terminology when discussing published dental injury data. Dental, orofacial, and maxillofacial injuries are often treated as equal and interchangeable definitions to support varied opinions regarding injury prevention and treatment.

As provided by Diangelis and Bakland,2 the World Health Organization defined dental injuries as fractures, luxations, and avulsions of teeth and fractures of the mandible or maxilla. Soft tissue oral injuries were not included because of the variability of injury classification (bruising to lacerations). Jaw contusions and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) episodes were not recorded for the same reason. Roberts3 defined dental injuries as fractures, avulsions, and luxations along with lip and oral mucosal lacerations, jaw fractures, TMJ cartilage injuries, and concussions.

In their definition of oral and dental injuries, Lephart and Fu4 included soft tissue injuries, maxillary fractures and dislocations, tooth fractures, luxations, and avulsions. Dale5 used the term dentoalveolar trauma to discuss dental injuries and included teeth injuries (fractures, avulsions, and luxations), alveolar injuries (mandible and maxilla), and all soft tissue injuries (lips, gums, and tongue), ranging from bruising to severe lacerations.

Orofacial injuries have also been defined inconsistently in the literature. Berg et al6 classified soft tissue injuries (cut lip, tongue, or cheek), bruised face, loose teeth, broken teeth, and facial fractures as orofacial injuries. Chapman7 included dental, dentoalveolar, intraoral, and perioral lacerations and jaw fractures in his definition. Flanders and Bhat8 included soft tissue injuries to the face and mouth and fractures of the facial bones, TMJ, and dentition. Kvittem et al9 reported on orofacial injuries but did not give a definition of “orofacial.”

Maxillofacial injuries have equally varied definitions. Sane et al10–13 defined facial skeleton and dental hard tissue injuries as maxillofacial injuries. Soft tissue injuries were not included. Tanaka et al14 reported fractures to the jaw and alveolus as maxillofacial injuries. Hildebrandt15 defined fractures to the bony structures of the jaw and face, dental injuries (tooth only), and soft tissue injuries to the lips, tongue, and mouth as maxillofacial injuries.

Powell and Barber-Foss16 stated that in order to conduct large data-collection projects, common operational definitions must be used to identify reportable events. Powell17 defined an injury as an episode resulting in at least 1 day lost from activity. Beachy et al18 defined an injury as any episode requiring evaluation, regardless of time lost. Injury severity was determined using days lost from activity.

Tesini and Soporowski1 recommended a dental data-reporting system allowing for injury comparison with an established definition for a reportable injury event. This would permit the collection of appropriate data while acknowledging limitations and sources of error.

For the purposes of this 15-year study, I restricted dental injuries to those involving the jaw (contusions, fractures, and TMJ), teeth (concussions, fractures, luxations, and avulsions), and any oral soft tissue (lip, mouth, and tongue) and requiring dentist or physician referral. Other soft tissue injuries were treated as skin abrasions and not recorded. An injury was defined as any episode requiring evaluation, regardless of time lost. Injury severity was determined by days lost from activity: minor (0 days lost), mild (1–7 days lost), moderate (8–21 days lost), or severe (22+ days lost).

Published specific sport-related dental-injury data have been anecdotal, retrospective, or prospective in nature. Although interesting, anecdotal reports are of limited scientific value. Unfortunately, speculative anecdotal reports regarding mouth-guard use and the prevention of concussions have been given unwarranted credibility19 in the dental community. Kumamoto et al20 presented a sensational case study of tooth entanglement in a basketball net, which, while interesting, is certainly not a common occurrence.

Retrospective studies7,11–13,21–24 have both recall and subjectivity biases. Injury rates are not available for these studies, thereby furthering the difficulty of study comparison. Retrospective questionnaires often ask for career sport-related dental-injury information21,22 or injury reporting at the end of the season.23 The exposure data are generally estimated, and the injury recall is less than complete. This is equally true for data collected from hospitals13,14,25–29 and from insurance forms,10–12,24 as only the more severe injuries, not all injuries, are generally reported.

The attitudes and opinions of coaches and athletes regarding dental injuries6 and mouth-guard use7 can be erroneously interpreted as hard data. Errors in data presentation raise further questions about the validity of various studies. Flanders and Bhat8 reported the injury rate at 1/10 000 exposures rather than the standard of 1/1000 exposures, creating possible problems in interpretation if this difference is overlooked. Bolhuis et al,21 while reporting on field hockey dental injuries, presented dental injury data that may be confused with mouth-guard use.

The lack of standardized dental-injury definitions further complicates the comparison of published injury data. DeLee and Farney30 did not define a facial or dental injury, and Gomez et al31 similarly lacked an injury definition. Blignaut et al32 included nasal fractures, although the nose cannot be protected by a mouth guard.

Morrow et al33,34 completed an extensive study of dental injuries to collegiate athletes, including chin lacerations in the definition of dental injuries. Morrow et al35 also conducted a prospective study of the dental injury rate of female basketball players, all of whom were provided with custom-fitted mouth guards. The definition of an oral injury was not presented; however, episodes of injury were fewer in those wearing the custom mouth guard. A similar comparison using boil-and-bite mouth guards is warranted.

Ranalli and Rye36 reported that maxillary anterior tooth injuries were the most frequently reported dental injury. They also noted that males have a 1.5 times higher rate of injury than females when not wearing mouth guards. Zelisko et al37 found a 1.6 times higher risk for male professional basketball players as compared with their female counterparts. Schmidt-Olsen et al38 reported a correlation between age and injury in soccer tournament participants. The older the player, the higher the risk of injury. Sane and Ylipaavalniemi11 noted that male soccer players over age 20 were at higher risk of dental injury.

METHODS

Subjects

I conducted a 15-year (1988–2003) longitudinal study of dental athletic injuries occurring to students in grades 7 to 12 at a private Honolulu school with an enrollment of 3500 from grades kindergarten to 12. Of the average 2445 students (range, 2399–2479) enrolled in grades 7 to 12 from 1988 to 2003, 50% (623 of 1243) of all females and 60% (717 of 1193) of all males annually participated in interscholastic sports.

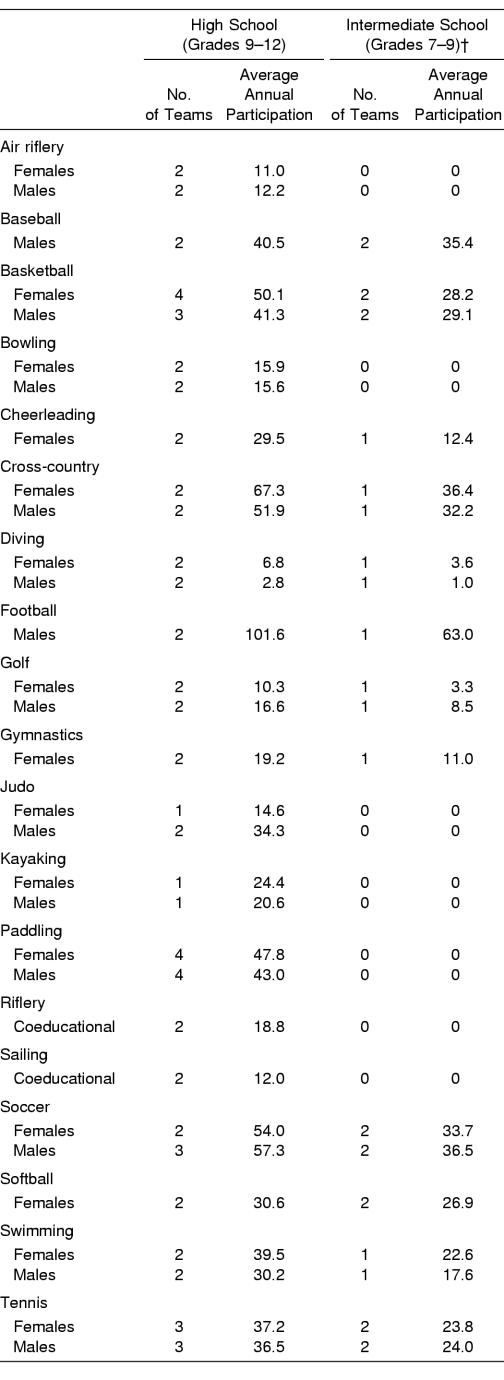

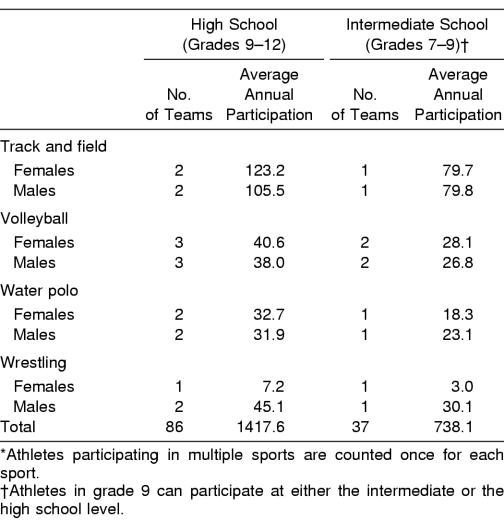

Thirty-nine sports (19 female, 18 male, 2 coeducational) (Table 1) and 123 teams constituted the interscholastic athletic program. Multiple-sport athletes were counted once for each sport. On average, intermediate teams (grades 7–9) included 331 females and 407 males. High school participants annually averaged 662 females and 725 males.

Table 1. Punahou School Teams and Average Annual Participation, 1988–2003*.

PROCEDURES

Injury Definition

An injury was defined as any complaint that required the attention of a certified athletic trainer (ATC), regardless of the time lost from activity. A day-lost injury was any injury resulting in a minimum of 1 day lost from activity.

Dental Injury Definition

Dental injuries were restricted to the jaw, teeth, and oral soft tissue (lip, mouth, cheek, and tongue). Soft tissue injuries requiring physician or dentist referral were recorded. Other soft tissue injuries were treated as skin abrasions and not recorded.

Tooth Injury Definition

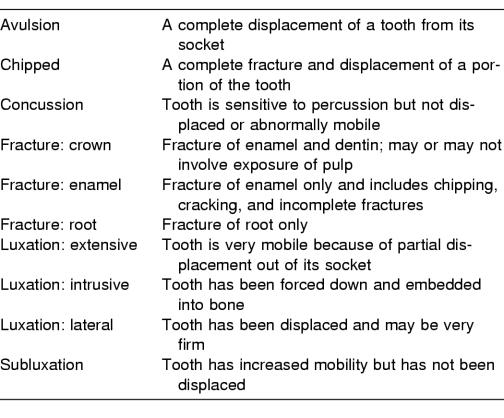

The standard nomenclature of the World Health Organization, as noted by Diangelis and Bakland,2 was used to define tooth injuries (Table 2).

Table 2. World Health Organization Tooth Injury Definitions as Reported by Diangelis and Bakland2.

Data Collection

Three full-time ATCs evaluated all injuries. Injury data were recorded daily using a database program I designed. The 5 injury classifications as presented by Beachy et al18 were (1) minor: no time lost, (2) mild: 1 to 7 days lost, (3) moderate: 8 to 21 days lost, (4) severe: 22+ days lost, and (5) catastrophic: permanent disability or death. Athletes reported 56 dental injuries, including 32 (60%) days-lost injuries.

Injury Data

An athlete-session consisted of 1 practice session or game. I estimated the injury rate (injuries per 1000 athlete-sessions) for all sports and levels. The number of athletes per sport per year was multiplied by the number of practices and games in the season. A team of 15 athletes practicing for 5 days would record 75 athlete-sessions of exposure. The number of days lost from activity due to injury was determined and then subtracted from the exposures. Intermediate and junior varsity teams averaged 60 to 72 days per season. Varsity teams averaged 84 to 96 days per season. Depending on the sport, state tournament competition may add an additional 6 to 14 days to the varsity schedule. The 95% confidence interval was included to address any random variations that might be present in the data.

Mouth-Guard Use

Boil-and-bite mouth guards were provided to all football players, with replacement during the season as necessary. Custom-fitted mouth guards were worn by approximately 10% of the football athletes, but the actual number of mouth guards worn for all sports was not recorded. Mouth-guard type was not a factor in this study.

All interscholastic athletes were offered the use of one brand of boil-and-bite mouth guard. Athletes wearing orthodontic appliances were encouraged to wear mouth guards to prevent lip abrasions. Wrestling and judo participants were encouraged but not required to use mouth guards. An estimated small percentage of soccer and basketball players, both male and female, used a mouth guard. The ATCs distributed and monitored the fitting of approximately 350 boil-and-bite mouth guards per year.

RESULTS

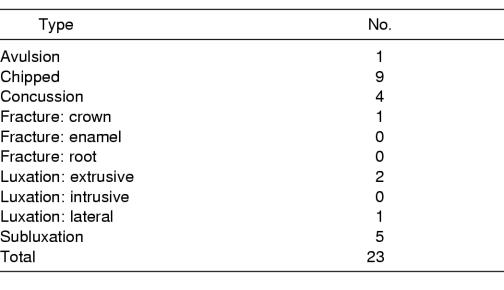

From 1988 to 2003, 19 492 injuries were reported, with 56 (0.2%) recorded as dental injuries. The dental injuries included 23 tooth injuries (43%), 20 jaw injuries (33%), and 13 soft tissue injuries (24%). Only 2 episodes involved multiple teeth. For recording purposes, each tooth was treated as a separate injury.

Tooth injuries are shown in Table 3. Eight of the chipped teeth and 1 concussed tooth did not result in time lost from activity, as the injuries were reported at the end of practice and the athletes were cleared by their dentists to return to activity the next day. One soccer player lost 102 days from activity as a result of an avulsion and extrusive luxation. Football players did not report any tooth injuries. Football has a mandatory mouth-guard requirement.

Table 3. Types and Numbers of Tooth Injuries, Punahou School, 1988–2003.

Two jaw fractures were reported during the 15-year study. One jaw fracture was the result of a thrown ball, and the other was due to a fall. The remaining jaw injuries were contusions resulting from thrown balls (4) and physical contact in a variety of sports (14).

Twelve of the 13 soft tissue injuries referred for physician or dentist evaluation required sutures. The tongue laceration did not require sutures. A total of 22 days was lost from activity. All physicians allowed the injured athletes to return to activity before the sutures were removed.

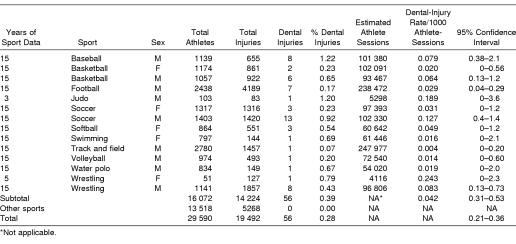

Athletes in 14 sports sustained dental injuries (Table 4). Male soccer participants reported the most dental injuries, 13, during the 15-year study. Male wrestling and baseball followed with 8 each and then football with 7 dental injuries.

Table 4. Punahou School Interscholastic Dental Injuries and Injury Rates, 1988–2003.

The athlete dental-injury rate (injuries per 1000 athlete-sessions) was highest for female wrestling participants at 0.243, followed by male judo athletes at 0.189. Both sports have low participation rates and injury totals. In sex-matched sports, except for wrestling, males had a higher dental-injury rate. Male wrestlers had an injury rate of 0.083, and no female judo athletes sustained a dental injury. The injury rate for male soccer players was 0.127, compared with 0.031 for female soccer players. The injury rate for male basketball players was 0.064, compared with 0.020 for female basketball players. Baseball players recorded a 0.079 injury rate, compared with the softball players' rate of 0.049. Football players recorded an injury rate of 0.029. Noncontact sports participants in water polo, swimming, volleyball, and track recorded the lowest injury rates.

Fifteen dental injuries (26.8%) were reported during games: 8 tooth injuries, 6 jaw injuries, and 1 soft tissue injury. Seven athletes returned to competition that day. Nearly 3 times the number of dental injuries were reported during practice, which is in line with the greater time spent in practice. Exact injury rates for practices and games could not be established.

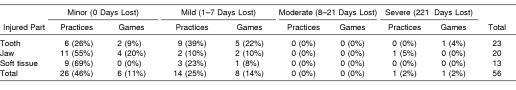

Injury severity is determined by days lost from activity. As noted in Table 5, 32 of the injuries (57%) were minor, with no days lost from activity. Six of the minor injuries occurred during games and 26 during practices. The 22 mild injuries (1 to 7 days lost) accounted for 79 days lost from activity. The 2 severe injuries (jaw fracture and tooth avulsion) resulted in 131 days lost from activity.

Table 5. Severity of Dental Injuries Incurred in Punahou School Practices and Games: Frequency (%).

Except for the 7 football injuries (with no tooth involvement), none of the injured athletes was wearing a mouth guard at the time of injury.

DISCUSSION

This study is unique in that the same ATCs evaluated and recorded all athletic injuries occurring to intermediate and high school student-athletes participating in interscholastic competition during this 15-year period (1988–2003). The same injury definitions and evaluation criteria were used throughout the study.

Little information is available about dental injuries to high school–aged athletes. Published high school sport injury reports by Beachy et al,18 McLain and Reynolds,39 and Powell and Barber-Foss16 designated injuries to the head and face/ scalp only. Gomez et al,31 Kvittem et al,9 Messina et al,40 Nilsson and Roaas,41 Pasternack et al,42 Pasque and Hewett,43 and Seals et al44 have reported on high school dental injuries in a variety of sports, with most studies being either 1 or 2 years in duration and using various definitions.

Nilsson and Roaas,41 Hoff and Martin,23 Schmidt-Olsen et al,38 and Sane and Ylipaavalniemi11 have studied soccer dental injuries, and DeLee and Farney30 and Garon et al22 have researched football dental injuries. Inconsistent injury definitions, along with variations in reporting, do not allow for comparisons with this study.

Labella et al45 compiled the most complete dental-injury data for collegiate male basketball players using an injury definition consistent with this study. They noted that those athletes wearing mouth guards had a lower dental-injury rate. Messina et al40 reported that male basketball players sustained more dental injuries than female basketball players, which is consistent with the data reported in this study. No injury rates were provided for comparison.

Morrow et al33,34 reported on oral injuries in female and male volleyball players. The inclusion of chin lacerations is problematic and inconsistent with other dental-injury definitions, making comparison with this study difficult.

Published dental-injury data for judo, swimming, water polo, and track participants are lacking.

During the 15 years of this study, the use or nonuse of mouth guards was recorded for all dental injuries at the time of injury. The type of mouth guard was not a factor in this study, as no tooth injuries were recorded for athletes wearing mouth guards. Boil-and-bite mouth guards were distributed to all football players and offered to all athletes participating in the interscholastic athletic program.

In the high school setting, because of staffing limitations and the number of sports and teams, it is impossible for an ATC to be in attendance at every practice or game. Nonreported injuries, including dental injuries, may occur. Coaches and athletes are asked to report any injuries to the ATCs on their return to campus, either the same day or the next. Not having an ATC at all events could prove to be a limitation of this study.

Lacrosse, ice hockey, and field hockey have national mandatory mouth-guard requirements. These sports are not part of the Punahou School interscholastic program, and results presented here cannot be applied to those sports.

Discussions regarding the use of mouth guards in preventing concussion have been speculative,19 and as noted by McCrory,46 few scientific data support this hypothesis. This topic was not a focus point for my study but certainly requires further scientific study.

CONCLUSIONS

The incidence and injury rate of dental injuries is extremely low for all reported sports. Although mouth guards effectively prevent tooth injuries, the necessity for custom-fitted mouth guards for athletes in contact sports is brought into question. Further research using the same definitions and evaluation criteria is warranted. Based on the experiences of the full-time ATCs at Punahou School, those athletes wearing orthodontic appliances while competing in contact sports should wear mouth guards to prevent the soft tissue abrasions that occur during practices and competitions.

The lack of a universally accepted definition for dental injuries has allowed individual researchers latitude in defining and collecting injury data. Therefore, replications of dental-injury studies are often difficult or impossible to complete. Injury rates must be presented to facilitate comparison of published data. Until these problems are addressed, anecdotal and speculative data will continue to dominate the discussion of dental injuries in athletes. The dental community and allied health personnel, including ATCs, need to address these issues in order to provide guidance for researchers, coaches, and athletes in the area of athletic dental injuries.

Table 1. Continued.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dr Jack Belli for his statistical input and to Beth Young, ATC, and Matt Martinson, ATC, for their expertise and support in maintaining a high standard of care for the Punahou athletes. Thanks also to Cedric Akau, MD, and Tim Olderr, MD, from Straub Sports Medicine for their encouragement in presenting this paper for publication.

REFERENCES

- Tesini DA, Soporowski NJ. Epidemiology of orofacial sports-related injuries. Dent Clin North Am. 2000;44:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diangelis AJ, Bakland LK. Traumatic dental injuries: current treatment concepts. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1401–1414. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WO. Field care of the injured tooth. Physician Sportsmed. 2000;28(1):101–102. doi: 10.3810/psm.2000.01.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lephart SM, Fu FH. Emergency treatment of athletic injuries. Dent Clin North Am. 1991;35:707–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale RA. Dentoalveolar trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:521–538. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg R, Berkey DB, Tang JM, Altman DS, Londeree KA. Knowledge and attitudes of Arizona high-school coaches regarding oral-facial injuries and mouthguard use among athletes. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1425–1432. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman PJ. Orofacial injuries and international rugby players' attitudes to mouthguards. Br J Sports Med. 1990;24:156–158. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.24.3.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders RA, Bhat M. The incidence of orofacial injuries in sports: a pilot study in Illinois. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:491–496. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvittem B, Hardie N, Roettger M, Conry J. Incidence of orofacial injuries in high school sports. J Public Health Dent. 1998;58:288–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1998.tb03011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sane J. Comparison of maxillofacial and dental injuries in four contact team sports: American football, bandy, basketball, and handball. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:47–51. doi: 10.1177/036354658801600616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sane J, Ylipaavalniemi P. Maxillofacial and dental soccer injuries in Finland. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;25:383–390. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(87)90087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sane J, Ylipaavalniemi PL, Leppanen H. Maxillofacial and dental ice hockey injuries. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1988;20:202–207. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198820020-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sane J, Lindqvist C, Kontio R. Sports-related maxillofacial fractures in a hospital material. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;17:122–124. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(88)80165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Hayashi S, Amagasa T, Kohama G. Maxillofacial fractures sustained during sports. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54:715–719. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(96)90688-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt JR. Dental and maxillofacial injuries. Clin Sports Med. 1982;1:449–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell JW, Barber-Foss KD. Injury patterns in selected high school sports: a review of the 1995–1997 seasons. J Athl Train. 1999;34:277–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell JW. National High School Athletic Injury Registry. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(suppl 1):S134–S135. doi: 10.1177/03635465880160s126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beachy G, Akau CK, Martinson M, Olderr TF. High school sports injuries: a longitudinal study at Punahou School: 1988 to 1996. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:675–681. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenger JM, Lawton EA, Wright JM, Ricketts J. Mouthguards: protection against shock to head, neck, and teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;69:273–281. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1964.0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto DP, Winters J, Novickas D, Mesa K. Tooth avulsions resulting from basketball net entanglement. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128:1273–1275. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolhuis JH, Leurs JM, Flogel GE. Dental and facial injuries in international field hockey. Br J Sports Med. 1987;21:174–177. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.21.4.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garon MW, Merkle A, Wright JT. Mouth protectors and oral trauma: a study of adolescent football players. J Am Dent Assoc. 1986;112:663–665. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1986.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff GL, Martin TA. Outdoor and indoor soccer: injuries among youth players. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14:231–233. doi: 10.1177/036354658601400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller FO, Marshall SW, Kirby DP. Injuries in Little League baseball from 1987 through 1996: implications for prevention. Physician Sportsmed. 2001;29(7):41–48. doi: 10.3810/psm.2001.07.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CM, Burford K, Martin A, Thomas DW. A one-year review of maxillofacial sports injuries treated at an accident and emergency department. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:44–47. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(98)90747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CM, Crosher RF, Mason DA. Dental and facial injuries following sports accidents: a study of 130 patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;23:268–274. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(85)90043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis GS, Stewart ID. Rugby injury survey 1979. N Z Med J. 1981;94:349–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maladiere E, Bado F, Meningaud JP, Guilbert F, Bertrand JC. Aetiology and incidence of facial fractures sustained during sports: a prospective study of 140 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30:291–295. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Tomitsuka K, Shionoya K, et al. Aetiology of maxillofacial fracture. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;32:19–23. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(94)90166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLee JC, Farney WC. Incidence of injury in Texas high school football. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:575–580. doi: 10.1177/036354659202000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez E, DeLee JC, Farney WC. Incidence of injury in Texas girls' high school basketball. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:684–687. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blignaut JB, Carstens IL, Lombard CJ. Injuries sustained in rugby by wearers and non-wearers of mouthguards. Br J Sports Med. 1987;21:5–7. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.21.2.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow RM, Bonci T. A survey of oral injuries in female college and university athletes. Athl Train J Natl Athl Train Assoc. 1989;24:236–237, 287. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow RM, Seals RR, Barnwell GM, Day EA, Moore RM, Stephens MK. Report of a survey of oral injuries in male college and university athletes. Athl Train J Natl Athl Train Assoc. 1991;26:338–342. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow RM, Bonci T, Seals RR, Barnwell GM. Oral injuries in Southwest Conference women basketball players. Athl Train J Natl Athl Train Assoc. 1991;26:344–345. [Google Scholar]

- Ranalli DN, Rye LA. Oral health issues for women athletes. Dent Clin North Am. 2001;45:523–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelisko JA, Noble HB, Porter M. A comparison of men's and women's professional basketball injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1982;10:297–299. doi: 10.1177/036354658201000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Olsen S, Bunemann LKH, Lade V, Brassoe JO. Soccer injuries of youth. Br J Sports Med. 1985;19:161–164. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.19.3.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLain LG, Reynolds S. Sports injuries in a high school. Pediatrics. 1989;84:446–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina DF, Farney WC, DeLee JC. The incidence of injury in Texas high school basketball: a prospective study among male and female athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:294–299. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270030401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson S, Roaas A. Soccer injuries in adolescents. Am J Sports Med. 1978;6:358–361. doi: 10.1177/036354657800600608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternack JS, Veenema KR, Callahan CM. Baseball injuries: a Little League survey. Pediatrics. 1996;98:445–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasque CB, Hewett TE. A prospective study of high school wrestling injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:509–515. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280041101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals RR, Morrow RM, Kuebker WA, Farney WD. An evaluation of mouthguard programs in Texas high school football. J Am Dent Assoc. 1985;110:904–909. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1985.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labella CR, Smith BW, Sigurdsson A. Effect of mouthguards on dental injuries and concussions in college basketball. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:41–44. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrory P. Do mouthguards prevent concussions? Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:81–82. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]