Abstract

Objective: To gain insight regarding the mentoring processes involving students enrolled in athletic training education programs and to create a mentoring model.

Design and Setting: We conducted a grounded theory study with students and mentors currently affiliated with 1 of 2 of the athletic training education programs accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs.

Participants: Sixteen interviews were conducted, 13 with athletic training students and 3 with individuals identified as mentors. The students ranged in age from 20 to 24 years, with an average of 21.6 years. The mentors ranged from 24 to 38 years of age, with an average of 33.3 years. Participants were purposefully selected based on theoretic sampling and availability.

Data Analysis: The transcribed interviews were analyzed using open-, axial-, and selective-coding procedures. Member checks, peer debriefings, and triangulation were used to ensure trustworthiness.

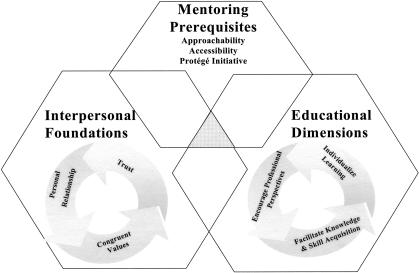

Results: Students who acknowledged having a mentor overwhelmingly identified their clinical instructor in this role. The open-coding procedures produced 3 categories: (1) mentoring prerequisites, (2) interpersonal foundations, and (3) educational dimensions. Mentoring prerequisites included accessibility, approachability, and protégé initiative. Interpersonal foundations involved the mentor and protégé having congruent values, trust, and a personal relationship. The educational dimensions category involved the mentor facilitating knowledge and skill development, encouraging professional perspectives, and individualizing learning. Although a student-certified athletic trainer relationship can be grounded in either interpersonal or educational aspects, the data support the occurrence of an authentic mentoring relationship when the dimensions coalesced.

Conclusions: Potential mentors must not only be accessible but also approachable by a prospective protégé. Mentoring takes initiative on behalf of a student and the mentor. A mentoring relationship is complex and involves the coalescence of both interpersonal and educational aspects of an affiliation. As a professional-socialization tactic, mentoring offers students a way to anticipate the future professional role in a very personal and meaningful way.

Keywords: mentor, protégé, anticipatory socialization, qualitative research

Mentoring is widely accepted as a strategy for facilitating the professional growth and development of students while they are socialized into a discipline.1 As a component of the professional-socialization process, mentoring can influence how individuals prepare themselves and develop various values, skills, knowledge, and attitudes throughout their academic and professional careers.2 Indeed, successful student experiences are frequently connected to mentoring processes3 that may serve to help them achieve their optimal potential, not only as health care providers but also as organizational leaders.4,5

No definition of mentoring is universally accepted,6,7 but regardless of whether mentoring occurs formally or informally, the goal is to enhance an individual's development of a professional role2 by way of a relationship with a more experienced person.8 Recently, the athletic training literature has revealed the importance of mentoring8,9 for professional development. For example, Malasarn et al8 identified mentoring as a critical role in developing expert certified athletic trainers (ATCs). Pitney et al9 discovered that many ATCs in the intercollegiate setting relied on advice from previous mentors to guide their learning and meet the demands of their new roles. As Curtis et al10 reported, athletic training students (ATSs) desired supervisors to demonstrate mentoring behaviors such as constructive feedback, explanation, and nurturing, and these mentoring roles have a profound effect on an ATS's professional development.

Although mentoring is considered a key component of learning a professional role2 and some insight has been gained about mentoring behaviors,10 there is a paucity of research explicitly investigating and elucidating the mentoring processes in undergraduate athletic training curriculums. Athletic training students face a variety of professional development challenges during the anticipatory socialization process due to the complexity of academic, clinical, and professional environments. Based on the aforementioned literature, mentoring is intuitively a viable strategy to mitigate these challenges, facilitate the successful socialization and acculturation of ATSs, and positively influence professional development. Given the efficacy of mentorship in the anticipatory socialization of professionals, the significance of this study lies in gaining insight about the mentoring experiences of undergraduate ATSs and furthering our understanding of mentoring process intricacies. With the continued goal of improving clinical education and ATSs' acculturation, this research will serve to improve our understanding of mentorship in athletic training.

Our purpose was to gain insight and understanding of the mentoring processes and to generate theory related to mentoring ATSs. The following central questions guided this study:

By what processes are ATSs mentored?

What is the nature of these mentoring relationships, and how does it contribute to the students' professional socialization?

How do students perceive their various mentoring experiences relative to learning their professional roles as future ATCs?

METHODS

We identified qualitative methods, specifically grounded theory, as an exceptional strategy because of the study's focus on gaining insight about a social process and the explicit attempt to generate a theoretic model.11,12 Moreover, Maxwell11 stated that the personal meaning informants place on a particular situation, event, or action is generally a strength of qualitative research and coincided nicely with the purpose of this study: to understand the mentoring process.

The theoretic base of grounded theory is symbolic interactionism,13,14 which was the theoretic framework for this study. Symbolic interactionism infers that an individual's behavior is formed by social interactions; individuals are active in this process, and they make conscious decisions about how they will act in a given situation.15 As Blumer16 clarified, from a symbolic interactionist's position, a social setting (ie, clinical interactions between a clinical instructor [CI] and an ATS) can create a condition for personal action and perception (readers should refer to Blumer16 for a more detailed explanation of symbolic interactionism). Symbolic interactionism thus focuses on the meaning that individuals give to interactions with others.

This study received initial institutional review board approval from Northern Illinois University before data collection. Additional institutional review board approval was obtained from all educational institutions at which data were collected. Before the interviews, questions regarding the procedures were addressed and participants provided informed consent. Verbal consent to be audiotape recorded before the formal interview was also obtained from the participants.

Participants

Sixteen interviews were conducted, 13 interviews with ATSs and 3 with individuals identified as mentors. The ATSs ranged in age from 20 to 24 years, with an average of 21.6 years. The mentors ranged from 24 to 38 years, with an average of 33.3 years. Participants were purposefully selected based on theoretic sampling and availability. Participants were from 2 Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs-accredited athletic training education programs (9 from institution A and 7 from institution B). Institution A was a state-supported university with an enrollment of 15 000 to 20 000 undergraduate students in a metropolitan region. Institution B was a state-supported comprehensive university with an enrollment of 10 000 to 15 000 undergraduate students in a rural setting. During each of the student interviews, we asked for permission to interview the student's mentors. Three students agreed to put us in contact with their mentors.

We communicated with the program director at one institution and a staff athletic trainer and faculty member at the other institution to guide us in selecting participants based on the belief that they would be willing to offer personal perceptions of their mentoring experiences. This method of qualitative data sampling, the deliberate choosing of informants based on a belief that the informant is a person capable of supplying important information, is known as purposive sampling.17 Holstein and Gubrium17 stated that selecting participants because they are likely to describe their perceptions and experience underscores the theoretic commitment of purposive-sampling procedures in interpretive research.

One type of purposive sampling is theoretic sampling. The goal of theoretic sampling is to enable the researcher to seek out individuals who are able to help answer the research questions and, thus, offer the best chances for creating solid theory.18,19 We attempted, therefore, to recruit students who were nearing the end of their academic program (0.5–1 semester remaining) as well as those who had several semesters of clinical experience remaining. We also found it insightful to interview 3 students without mentors.

Data Collection and Analysis

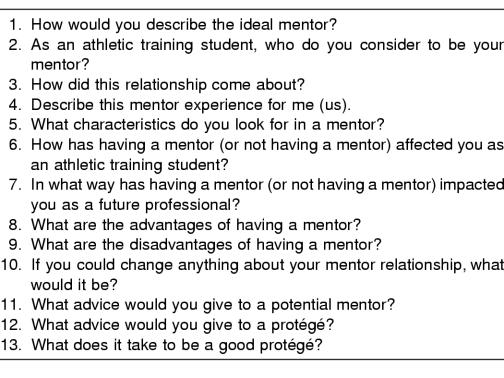

Individual interviews were conducted using a semistructured technique, and all ATSs were asked a set of core questions (Table). Questions were modified slightly for each of the interviews with mentors to make them more germane. For example, we asked the mentors the following: (1) How did the mentoring relationship with the student come about? (2) What characteristics do you think your students look for in a mentor? (3) How might either having or not having a mentor affect an athletic training student? The interviews were tape recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim. We conducted the first 5 interviews together with each participant in order to gain familiarity with the question-posing procedures before conducting separate interviews.

Semistructured Interview Guide.

For the inductive analysis, we used grounded theory procedures described by Strauss and Corbin.19 Grounded theory is a systematic approach for the collection and analysis of qualitative data for the purpose of generating explanations that further the understanding of social and psychological phenomena.20 The grounded theory approach consists of identifying specific concepts in the transcripts that explained and gave meaning to the social process of mentoring. The concepts were labeled and then organized into like categories, consistent with open-coding procedures.

Open coding of the transcripts was completed separately as the data were collected, but we communicated frequently as we reflected on the data. Consistent with grounded theory methods, data were collected until saturation was achieved. That is, data were collected until we identified redundancy in the data and were not uncovering any new concepts. In our professional judgment, data saturation was obtained by the 10th student interview. We interviewed 3 more ATSs to ensure that no new data were forthcoming.

Once the open coding was completed separately, we suspended our independent judgments regarding the categories that were created individually and worked together to systematically reorganize our combined concepts into categories. Repeating the open coding together essentially allowed us to repeat the procedures and articulate our understanding of the data. The newly created categories were labeled and compared with the independently created categories of textual data. We also shared research memoranda and assumptions to explain and negotiate both how and why particular concepts were important.

Axial and selective coding was performed after the open coding. We completed the axial-coding procedures together and explored how each of the categories related to one another, which allowed us to transform categories to subcategories and identify broader thematic categories based on the data. The selective coding allowed us to identify conceptual ideas that integrated the existing categories.

Trustworthiness

Triangulation, a peer review, and member checks21,22 were used to establish trustworthiness of the data collection and analysis. Data-source triangulation was performed by collecting data from protégés, mentors, and students who indicated they did not have a mentor. Collecting data from these 3 sources allowed us to cross-check information and more fully understand the mentoring process.19

A colleague with expertise in qualitative methods conducted the peer review by examining the interview transcripts, coding sheets (which identified concepts, categories, and properties), and a synopsis of the findings. Three leading questions were identified in the transcripts, and data received from those questions were eliminated from analysis. The peer review identified the analysis as being completed in a logical and systematic manner, and the findings were reasonable and accurate based on the interview data.

Member checks were conducted by consulting 4 of the participants (3 ATSs and 1 mentor). Each participant examined the results and agreed the findings were consistent with his or her experiences.

RESULTS

Participants who were currently involved in a mentoring relationship always identified their immediate CI and/or clinical supervisor as their mentor. In each instance of mentoring, the ATS and CI had a relationship founded on interpersonal connections (interpersonal foundations category) and focused on the educational needs of the student (educational dimensions category). These aspects of the mentoring relationship developed when particular mentoring prerequisites were met (mentoring prerequisites category). These 3 categories are the subcategories fully explained in the ensuing paragraphs. We conclude the Results section by presenting a model of mentoring experiences.

Mentoring Prerequisites

Several prerequisites for an effective mentoring relationship were identified. Mentoring prerequisites refers to the 3 aspects of an early affiliation that allowed for the mentoring process to initiate: accessibility, approachability, and protégé initiative.

The participants suggested that a potential mentor needs to be accessible for a mentoring relationship to evolve. When asked what characteristics she would look for when attempting to find a mentor, Karen stated, “Well, accessibility is … kind of a big thing for me. If I … ever need questions answered or need any ideas, [I need] for [my mentor] to be there [for me].” Sandy reflected this same concept when she discussed why she was not involved in a mentoring relationship: “A lot of times I felt like we were … really busy … more time constraints really, it seems like everything was … rushed … and we didn't usually have easy access to people.” Our data suggest effective mentors are able to balance their time so that they are available to the students.

The second important subcategory of the mentoring prerequisites category is approachability. Student participants suggested when individuals were accessible, approachability was important for a mentoring relationship to develop. From the students' perspective, approachability hinged on feeling respected by the CI and not being made to feel demoralized during a personal interaction. For example, Jenny stated,

I think that for me … [my mentor is] someone that I could go up and ask [a] question to and feel like they could give me the right answer. Somebody that would not try to [make me feel like] I'm so stupid. … Someone that would talk to me on a personal basis, not [indicating] that ‘I'm smarter than you.’ I wouldn't want to feel intimidated.

Some evidence suggested that aspects of a person's personality and attitude mediated the level of approachability. Students were less likely to approach a potential mentor if they were treated in a brusque and demeaning manner and more likely to approach a mentor if they felt respected.

The last prerequisite indicated by our data involved the student's responsibility. Indeed, our data suggest that mentoring relationships emerge not only because of a mentor's action but also because of a student's initiative. Thus, a mentoring relationship is truly a 2-way street. The participants stated that protégés should “ask questions,” “be good listeners,” “be patient,” “be inquisitive,” “be willing to actively learn,” and “show extra effort.” Tim voiced the following:

Don't sit back … and think everything's going to come to you. Go and ask questions, go and do things. Don't expect [your mentor] to give you everything in the world. It's on a 2-way basis, you help them, and they help you back. Don't expect a 1-way road and have them do everything for you and you do nothing for them because down the line they'll sit back and think about it and wonder what they really taught you.

Kenny also indicated the importance of protégé initiative:

I think before you can really get a mentoring relationship you … have to get to know the person; understand their quirks, their views, and what they [expect of you]. And I think that's what really gets someone interested in mentoring because you [as a student] show that interest, you show that willingness to work. And I think people are more willing to truly become a mentor. I mean you've got supervisors, but to me there's a difference between a supervisor and a mentor. And I think most people are more willing to be your mentor if you show that extra effort.

Interpersonal Foundations

The interpersonal foundations category that emerged from the data refers to the mentoring affiliation being founded on interpersonal connections. Interpersonal foundations related to 3 aspects of mentoring identified in the subcategories: (1) congruent values, (2) trust, and (3) personal relationships. Our data indicate these subcategories are closely interwoven, and the development of one led to the development of one or both of the other aspects. For example, trust seemed to be cultivated when both parties recognized the presence of congruent values.

Carrie reflected on the necessity of congruent values in a mentoring relationship when she stated, “… really to me … athletic training has a little bit to do with [developing a mentoring relationship], but there are lots of people who know about athletic training. It was more the way [my mentors] presented themselves and that they lived the same way they do in the [athletic] training room outside of the [athletic] training room.” The congruent values between a potential mentor and protégé fueled the interpersonal relationship. For example, Sue indicated that her mentor valued dedication, continual learning, and beneficence, all of which were congruent with her personal and professional characteristics. Carrie commented on valuing professionalism and described other relationships whereby the CI's values were not congruent with hers when she stated she has had supervisors “… who are very bad examples and they would go out and party with students and things like that. And I really like the example that [my current mentors have] set in that they don't do that.” Sue remarked that common goals and values are necessary components for a mentoring relationship. She stated that, when a student is attempting to find a mentor, he or she needs to step back and

… figure out what type of qualities you're looking for and goals you want to achieve and what you really want to get out of [the relationship]. And then once you've figured out what you want for yourself, go and find the person [with the] closest fit [with the] type of things you're looking for instead of just saying ‘oh this person looks … like somebody I could look up to’ and then realize that you might have 2 different agendas and it might not work out very well for you.

The recognition that congruent values were present helps to cultivate a trusting relationship. When asked what allowed for a mentoring relationship to develop with her and the ATSs, Carla stated, “I think we developed a great sense of trust between each other. And I hope that they see that I am really interested in helping them.” Sharon also reflected on the necessity of trust when she stated: “You know, personally, you just want a good quality person that you trust enough that I would let them work with me before … working with my athletes or vice versa.”

Trust allowed for more personal interactions between the ATS and CI, leading to an integration of professional and personal aspects of the relationship. One of the mentors in the study, when asked what allowed a mentoring relationship to develop and continue over time, explained that, “I've had … 4 or 5 [students] that … over the time we became friends and … I got to know [them] as more than just students.” Sharon continued by adding that the relationship was “intermixed with personal lives plus professional [aspects] and it kept the bond going.” Participants identified topics such as communicating on a personal level, eagerness to help, willingness to share experiences, availability as a listener, having a sense of humor, and caring about students on a personal level. Each of these represents common statements from the participants and helped to formulate the construction of this subcategory.

Educational Dimension

The participants consistently revealed that successful mentoring was inextricably linked to the process of learning and, thus, there was an educational dimension to the mentoring relationship. The educational dimension category contained the following subcategories: (1) facilitating knowledge and skill development, (2) individualizing learning, and (3) encouraging professional perspectives.

Facilitating knowledge and skill development was a primary focus in each of the mentoring relationships. Knowledge and skill development was based on students indicating their mentors helped them to not only understand what they needed to do to improve their skills but also helped them understand how to improve their critical thinking and problem solving. Moreover, mentors encouraged inquisitiveness, created appropriate learning experiences and a comfortable learning environment, and provided learning-related advice to their protégés. For example, when asked what she would look for in a mentor, Ann stated,

I want them to take the time and explain [aspects of athletic training] to me … in terms that I understand. I want them to [explain] what they're doing, and why they're doing it, so that I understand what I'm supposed to be learning. And if I have a question, I want them to be able to answer it or be able to find it for me, but I also want them to test my knowledge too.

Carrie also voiced the importance of facilitating knowledge and skill during a mentoring experience. She explained,

I think [my mentoring relationship] has been a good one because they kind of help us to learn. They take time out of [the day], instead of watching practice, [and] we go over certain things or we work on our worst taping [procedure] or work on certain muscle origins and insertions. We do stuff instead of just watching practice. … It seems like there's some big secret [in athletic training] … and … [my mentors are] open to telling us everything, and that's good.

In addition to facilitating knowledge and skills, individualizing the learning experiences and teaching strategies was important in the successful mentoring relationship. When asked what advice she would give to a mentor, Melinda stated,

I would say to … always take into account each individual that you're working with, not focus on everyone as a group, because everyone does learn differently. Everyone has different learning potentials and I think that focusing on each individual is very important for teaching each individual what they need to learn. … I feel like [my mentor has] really been able to kind of hone in on what I need and kind of go from there and really make sure to take care to always do that. … She's always willing to individualize things, which I think is very, very important.

Karen supported this concept when she stated mentors should provide for individual learning differences “because a lot of [students] are [at] different levels … whether they're supposed to be at [a particular skill] level or not. They are going to have questions that are different. … So [mentors shouldn't begin] thinking that these people are supposed to be at a level because they might not necessarily be.”

Another advantage a positive mentoring relationship offered was to encourage an understanding of professional perspectives. For example, Ann stated,

The advantage of having a mentor is that you get to learn and see from someone else's perspective. Then they can teach you what they know, and you can also see how someone else does it—everyone does something different. Everyone tapes ankles different, everybody treats their injuries different. … I think it just gives you examples to go from.

Even Carla commented on how mentoring helps provide a professional perspective:

First of all, it gives them an outside perspective when dealing with their peers and their classmates. With a mentor, you are going to get somebody, in our case in the same profession [that] is maybe a few years removed from being a student, and [it] just gives [the protégé] a different perspective.

From the protégés' standpoint, a mentor relationship that facilitated the students' understanding of professional perspectives was an important aspect of their anticipatory professional socialization; the students could envision what the ATC role would be like in different settings. For example, Lonnie stated that, as an ATS, there are different career directions you can take, and having a few mentors has helped him gain insight about the role of the ATC in different job settings. He stated,

Each [mentor has] had a different experience at a different level and a different job. … When I go look for a job … I have an understanding of what I might expect and what I might like about certain jobs compared to other ones.

In addition, Jason was asked to reflect on how his mentoring experience might influence him as a future professional. He commented,

I think it [the mentor relationship] gives you that diversity of different ways to go about doing something … and when I do become a professional … I'll have this knowledge [that] I don't necessarily have to do [a task] this way. … I can … get positive effects from doing something another way.

Carla also identified the need to give a perspective about what is expected of students as future professionals. She stated mentors should take that role seriously. “You are helping to set an example for preprofessionals in this case. And I think that it's important that we teach them early what is expected of them and what is appropriate and not appropriate.” She continued by adding that mentoring in athletic training is vitally important,

And in this profession it seems like it's very important because you can only learn so much in the classroom. And I think that it is hard to teach how do you interact with a coach, or how do you interact with athletes that sustain a season-ending injury or something. So I think it is important that [students] have someone … to learn things from. They may not agree with the entire style, but there are pieces that they can take and use.

Although few disadvantages of mentoring were noted, some students did speculate on the disadvantages of mentoring, specifically related to facilitating professional perspectives. The students indicated a single mentor might possibly give only one opinion and shield a protégé from understanding the perspectives of others. For example, when asked about a possible disadvantage of having a mentor, one participant stated “… you can see just their point of view, if you just think of one person as a mentor; so maybe you get kind of skewed and you just see their point of view and so you get one-track minded.” Even one of the participants who did not have a mentor stated, “… I guess because I'm just coming to depend on so many different people; there's a lot more different points of view. You know, I've seen a lot of different ways, I guess, of doing things.”

An Integrated Model

Completing the axial- and selective-coding procedures on the data allowed us to generate the following propositions. First, the prerequisites of approachability, accessibility, and protégé initiative are fundamental for the development of a mentoring relationship. Second, although a student-CI relationship can potentially be grounded in either interpersonal foundations or educational dimensions, an authentic mentoring relationship for the participants occurred when the mentoring prerequisites, interpersonal foundations, and educational dimensions coalesced. The Figure provides a conceptual model of mentoring in the undergraduate athletic training education programs produced from the analysis procedures. The model presents a uniform alignment of the mentoring dimensions, but theoretically a mentoring relationship could emphasize more or less of any given dimension.

A conceptual model of the mentoring processes.

Authentic mentoring occurs after the mentoring prerequisites are met and the interpersonal foundations and educational dimensions coalesce

DISCUSSION

Our findings revealed that, from the students' perspective, mentors must be accessible and approachable, but students must also take initiative in order for a mentoring relationship to develop. The athletic training education literature has identified accessibility as a key characteristic to effective clinical education.10,23 For example, Curtis et al10 determined that supervisor unavailability was frequently identified as hindering supervisory behavior. Moreover, while discussing effective instructional skills, Weidner and Henning23 stated that effective CIs remain accessible to students to answer questions and provide assistance when students are challenged.

Examining the relationships between the categories revealed that approaching a potential mentor was not likely to occur if an ATS perceived a mentor as threatening or disrespectful. Making students feel valued as individuals and using a communication style that is nonthreatening are both essential components of effective clinical instruction.23 In fact, demonstrating respect for the student and being accessible to students are highly ranked CI characteristics.24 Furthermore, a desirable learning experience involves a CI who is receptive to students.25 Clinical instructors should be aware of their mentoring responsibilities and demonstrate respect with a wide variety of students by showing a genuine concern for the students as people and learners.23

Just as teaching and learning is a 2-way street,5 so too is mentoring, in that students must take some initiative to cultivate a mentoring relationship. Students must ask questions and communicate with their CI for a relationship to develop.

Interpersonal Foundations

Interpersonal foundations are related to congruent values, trust, and a personal relationship between a protégé and his or her mentor. Our findings revealed that establishing trust was a significant aspect of a mentoring relationship and, according to Cohen,26 a mentoring relationship often begins with an emphasis on developing trust. A sense of trust and responsibility was recently implicated as a critical aspect of a positive educational environment within an athletic training education program27 and is consistent with our findings.

Accessibility, approachability, and protégé initiative are prerequisites to the development of a mentoring relationship. Arguably, however, trust may enter the approachability equation, as a student may not approach a CI if he or she does not trust and believe that he or she will be treated in a respectful manner. Trust, congruent values, and personal relationships were important to the ATSs and reflected a supportive dimension of mentoring as illuminated by Daloz.28 Supportive behaviors, such as assisting with clinical education as well as nonclinical educational or personal processes, are helpful for creating an environment that encourages student confidence and participation.10 Daloz,28 however, suggested that a mentoring relationship with a severe imbalance between challenge and support has the potential to negatively affect a protégé. For example, providing a great deal of support with little challenge may cause stagnation; having a great deal of challenge and little support may cause the protégé to retreat.28

Mentoring relationships are known to facilitate both an individual's career developmental and psychosocial functions in early and middle adulthood.7,29 The career developmental functions—typically related to a professional role within an organization—include such roles as sponsorship, exposure, visibility to decision makers, protection from mistakes, and challenging assignments. Psychosocial functions, on the other hand, have an interpersonal orientation and include counseling, acceptance, and friendship.30,31 Based on our data, the participants tended to identify more with the psychosocial functions of mentoring: namely trust, congruent values, and the development of a personal relationship. Our findings are consistent with those of Cameron-Jones and O'Hara,32 who discovered that both nursing students and nurse mentors believed the supporting role of a mentor was essential.

Educational Dimensions

The educational dimension category reflects the mentors' instructional interactions with the students. These interactions included facilitating knowledge and skill development, individualizing learning, and encouraging professional perspectives. From a developmental and instructional perspective, mentoring must consider the life-span developmental tasks that a protégé experiences.33 Individuals have varying needs based on their life developmental stage and their current goals. The ATSs in this study likely needed, or were required to learn, clinical proficiencies and professional behaviors that will aid them in their future professional roles. Accordingly, the educational dimensions emerged as a key component of mentoring relationships.

Individualized learning related to ATSs who believed their mentors accommodated their learning and provided for their individual differences. This is consistent with the literature in that an important task related to teaching and learning clinical skills is for CIs to tailor learning experiences so students not only acquire knowledge and skill but also the necessary attitudes to be future professionals.34

Encouraging a student's professional perspective combined with facilitating his or her knowledge and skills provided insight into the relationship between mentoring and the professional-socialization process. The anticipatory aspect of professional socialization relates to the formal education of undergraduate students and allows them to develop appropriate knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes and ultimately envision what it is like to be a future ATC.9 Our findings indicate mentoring relationships certainly play a role in the anticipatory professional-socialization process as ATSs learned from their mentors what to expect in their role as future professionals. Although students can conceivably learn to anticipate their future roles without involvement in a mentor relationship, other literature suggests a mentoring relationship provides a great deal of guidance, direction, and enrichment related to learning and developing in the professional role.8

Educational Implications

Athletic training education has recently focused on clinical instruction and the role of the CI in teaching and facilitating the professional development of ATSs.35 Clinical instructors serve many roles, including role model and mentor.5 Role modeling is thought to be more of a passive process, whereby students take on the values and behaviors of a CI by trying to emulate what they observe.36 Mentoring, on the other hand, requires active involvement by students as they engage in a personal relationship with an experienced individual to learn about the profession and promote professional socialization.36 Mentoring is a socialization strategy comprising nurturing an interpersonal relationship and addressing the educational needs of an ATS; mentoring can facilitate a student's development in undergraduate education1 and allows a student to view the discipline as a lifetime commitment. Arguably, a mentoring relationship during undergraduate education is vital to the professional-socialization process1 and, as indicated by Platt Meyer,5 appears to be related to effective clinical instruction.

Because mentoring appears to include many behaviors and characteristics associated with effective clinical education, athletic training education programs may benefit from addressing the mentoring processes related to the role of CIs. The model generated from this study explicates the complex nature of mentoring and the integrated relationship between the educational dimensions, interpersonal foundations, and various prerequisites necessary for the relationship to evolve. The model highlights the humanistic role of the CI in this process and underscores the importance of being both accessible and approachable while developing an interpersonal relationship based on trust and mutual respect. Clinical instructors should respect ATSs and encourage them to ask questions and take initiative in the learning process as much as possible. The model also underscores the importance of addressing individual learning needs associated with developing the knowledge and skills of ATSs.

Mentoring was generally viewed as a positive relationship by the participants. Indeed, when discussing the disadvantages of mentoring, the students were simply speculating. Despite the tremendous advantages of mentoring, the literature purports consumption of time, the possibility of reproducing the status quo, and lack of autonomy as possible problems with mentoring.37 That is, working closely with a protégé can be time consuming, and the relationship may lead to a protégé mirroring his or her mentor. Moreover, if a mentoring relationship is not properly conducted, a mentor may not allow a protégé to have adequate time for self-discovery and may even dominate the interactions that take place, leading to a lack of independence.

Limitations

Although the participants were affiliated with either a rural or metropolitan institution, both schools were public institutions of similar size. Students from private liberal arts schools may have different mentoring experiences to share. Perhaps a less homogeneous sample would expose other nuances of the mentoring process. This grounded theory investigation has created a model that transfers to similar contexts, but these qualitative research findings may not be generalized to all contexts. As such, athletic training educators and CIs must judge the verisimilitude of the findings and determine the extent to which the findings may inform their educational practices. Also, in retrospect, we believe a limitation exists in not having interviewed students who had just graduated from an athletic training education program. Asking students to reflect on their mentoring experiences after completing the curricular requirements may have offered additional insights.

CONCLUSIONS

Three questions guided this study: (1) By what processes are ATSs mentored? (2) What is the nature of the mentoring relationship, and how does it contribute to the students' professional socialization? (3) How do students perceive their various mentoring experiences relative to learning their professional roles as future ATCs? Completing the open-, axial-, and selective-coding procedures generated the following conclusions that answer these questions. First, related to the mentoring process, the prerequisites of approachability, accessibility, and protégé initiative are essential for the development of a mentoring relationship. Although an ATS-CI relationship can potentially be grounded in either interpersonal foundations or educational dimensions, the data support the fact that an authentic mentoring relationship for the participants occurred when the interpersonal foundations and educational dimensions coalesced. Second, related to the contributions to a student's professional socialization, the complex interlacing of interpersonal relations and educational dimensions allowed for the facilitation of knowledge and skill development at a very personal and individualized level. Third, the ATSs generally perceived their mentoring experiences as positive for not only helping them to develop appropriate technical skill and knowledge related to athletic training but also helping them to develop an understanding of professional perspectives related to their future professional responsibilities.

The mentoring model presented herein provides a first step toward understanding the mentoring perceptions and experiences of undergraduate ATSs. However, the extent to which mentoring facilitates future professional success in a variety of settings is not clear. Research seeking to correlate mentoring with success in the profession of athletic training should be undertaken. Although we used interviews with 3 mentors to triangulate the data, ATSs' perceptions and experiences of mentorship were primarily sought. Investigating the mentoring process from primarily the mentors' perspective may further elucidate our understanding of this phenomenon. With the continued emphasis on the importance of clinical education, future researchers should explore models and best practices of how to optimally integrate mentoring into Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Program–accredited curriculums.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant received from the Great Lakes Athletic Trainers' Association. Special thanks to Dr Linda Hilgenbrinck for her critical review of this project.

REFERENCES

- Ryan D, Brewer K. Mentorship and professional role development in undergraduate nursing education. Nurse Educ. 1997;22:20–24. doi: 10.1097/00006223-199711000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill HA. A qualitative analysis of student nurses' experiences of mentorship. J Adv Nurs. 1996;24:791–799. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.25618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldeck JH, Orrego VO, Plax TG, Kearney P. Graduate student/faculty mentoring relationships: who gets mentored, how it happens, and to what end? Commun Q. 1997;45:93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Allen DW. How nurses become leaders: perceptions and beliefs about leadership development. J Nurs Admin. 1998;28(9):15–20. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199809000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt Meyer LS. Leadership characteristics as significant predictors of clinical-teaching effectiveness. Athl Ther Today. 2002;7(5):34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gladwell NJ, Dowd DA, Benzaquin KO. The use of mentoring to enhance the academic experience. Schole: J Leis Stud Recreat Educ. 1995;10:56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kavoosi MC, Elman NS, Mauch JE. Faculty mentoring and administrative support in schools of nursing. J Nurs Educ. 1995;34:419–426. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19951201-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malasarn R, Bloom GA, Crumpton R. The development of expert male National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2002;37:55–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitney WA, Ilsley P, Rintala J. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I context. J Athl Train. 2002;37:63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis N, Helion JG, Domsohn M. Student athletic trainer perceptions of clinical supervisor behaviors: a critical incident study. J Athl Train. 1998;33:249–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JA. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. [Google Scholar]

- Brandriet LM. Gerontological nursing: application of ethnography and grounded theory. J Gerontol Nurs. 1994;20:33–40. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19940701-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall J. Axial coding and the grounded theory controversy. West J Nurs Res. 1999;21:743–757. doi: 10.1177/019394599902100603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annells M. Grounded theory method: philosophical perspectives, paradigm of inquiry, and postmodernism. Qual Health Res. 1996;6:379–373. [Google Scholar]

- Reutter L, Field PA, Campbell IE, Day R. Socialization into nursing: nursing students as learners. J Nurs Educ. 1997;36:149–155. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19970401-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1969. Symbolic Interactionism. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein JA, Gubrium JF. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. The Active Interview. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- Chenitz WC, Swanson JM. From Practice to Grounded Theory. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley; 1986. Qualitative research using grounded theory; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:1189–1208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- Weidner TG, Henning JM. Being an effective athletic training clinical instructor. Athl Ther Today. 2002;7(5):6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent T, Weidner TG. Clinical instructors' and student athletic trainers' perceptions of helpful clinical instructor characteristics. J Athl Train. 2001;36:58–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent T, Weidner TG. Clinical-education—setting standards are helpful in the professional preparation of employed, entry-level certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2002;37(4 suppl):S248–S254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NH. Malabar, FL: Krieger; 1995. Mentoring Adult Learners: A Guide for Educators and Trainers. [Google Scholar]

- Mensch JM, Ennis CD. Pedagogic strategies perceived to enhance student learning in athletic training education. J Athl Train. 2002;37(4 suppl):S199–S207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daloz LA. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1986. Effective Teaching and Mentoring. [Google Scholar]

- Kram KE. Phases of the mentor relationship. Acad Manage J. 1983;26:608–625. [Google Scholar]

- Koberg CS, Boss W, Goodman E. Factors and outcomes associated with mentoring among health-care professionals. J Vocat Behav. 1998;53:58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kram KE Hall DT Associates, editor. Career Development in Organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1986. Mentoring in the workplace; pp. 160–201. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron-Jones M, O'Hara P. Three decisions about nurse mentoring. J Nurs Manage. 1996;4:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head FA, Reiman AJ, Thies-Sprinthall L. The reality of mentoring: complexity in its process and function. In: Bey TM, Holmes CT, editors. Mentoring: Contemporary Principles and Issues. Reston, VA: Association of Teacher Educators; 1992. pp. 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Weidner TG, Trethewey J, August JA. Learning clinical skills in athletic therapy. Athl Ther Today. 1997;2(5):43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner G, Harrelson GL. Situational teaching: meeting the needs of evolving learners. Athl Ther Today. 2002;7(5):18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bidwell AS, Brasler ML. Role modeling versus mentoring in nursing education. Image J Nurs Sch. 1989;21:23–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1989.tb00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk E, Reichert G. The mentoring relationship: what makes it work? Imprint. 1992;39:20–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]