ABSTRACT

The ectodomain of matrix protein 2 is a universal influenza A virus vaccine candidate that provides protection through antibody-dependent effector mechanisms. Here we compared the functional engagement of Fcγ receptor (FcγR) family members by two M2e-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), MAb 37 (IgG1) and MAb 65 (IgG2a), which recognize a similar epitope in M2e with similar affinities. The binding of MAb 65 to influenza A virus-infected cells triggered all three activating mouse Fcγ receptors in vitro, whereas MAb 37 activated only FcγRIII. The passive transfer of MAb 37 or MAb 65 in wild-type, Fcer1g−/−, Fcgr3−/−, and Fcgr1−/− Fcgr3−/− BALB/c mice revealed the importance of these receptors for protection against influenza A virus challenge, with a clear requirement of FcγRIII for IgG1 MAb 37 being found. We also report that FcγRIV contributes to protection by M2e-specific IgG2a antibodies.

IMPORTANCE There is increased awareness that protection by antibodies directed against viral antigens is also mediated by the Fc domain of these antibodies. These Fc-mediated effector functions are often missed in clinical assays, which are used, for example, to define correlates of protection induced by vaccines. The use of antibodies to prevent and treat infectious diseases is on the rise and has proven to be a promising approach in our battle against newly emerging viral infections. It is now also realized that Fcγ receptors significantly enhance the in vivo protective effect of broadly neutralizing antibodies directed against the conserved parts of the influenza virus hemagglutinin. We show here that two M2e-specific monoclonal antibodies with close to identical antigen-binding specificities and affinities have a very different in vivo protective potential that is controlled by their capacity to interact with activating Fcγ receptors.

KEYWORDS: influenza A virus, M2e, viral infection, Fcγ receptors, mechanism of protection, IgG antibody isotype

INTRODUCTION

The ectodomain (M2e) of the influenza virus membrane protein M2 is an interesting candidate for a universal influenza vaccine. M2e vaccine-induced protection against influenza A viruses (IAV) is mainly conferred by antibodies (1–3). Although only some M2 molecules are incorporated into the virion, M2 is abundantly expressed on the surface of infected cells (4, 5). Hence, these cells are the most likely in vivo targets of M2e-based immune protection.

Influenza A virus infection elicits poor serum antibody responses against M2e (6, 7). Immunization with M2e fused to a heterologous carrier, however, readily induces M2e-specific antibody responses in animal models (1, 4, 5, 8–12). Some M2e vaccine candidates have reached early-stage clinical testing, which showed their safety and immunogenicity (11, 13). Despite these developments, there is still confusion about the mechanism of protection of M2e-specific responses. For example, a role for complement, natural killer cells, and alveolar macrophages has been proposed (2, 10, 14, 15). It is important to understand this in vivo mechanism in order to anticipate the potential immune evasion strategies of influenza viruses under the selection pressure of M2e-based immunity and to establish correlates of protection that are measurable by in vitro assays.

Fcγ receptor (FcγR) family members are crucial for protection by M2e-specific and broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin (HA)-specific IgG (2, 14–16). The mouse FcγR family comprises four members: three activating FcγRs (FcγRI, FcγRIII, and FcγRIV) and one inhibitory FcγR (FcγRIIB) (14, 15). We showed that polyclonal IgG1 isotype antibodies purified from mouse M2e immune serum required FcγRIII for immune protection and that the protection of Fcgr3-deficient mice could be restored by an IgG fraction containing M2e-specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies (2). That study, however, did not address the affinity of the purified IgG subclasses for M2e, nor did it address the protection conferred by IgG2a antibodies alone. Moreover, the possible role of mouse FcγRIV in the protection provided by anti-M2e IgG was unknown.

Here we compared the protective potential of two mouse monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) with very similar affinities for M2e but different Fc domains: MAb 37 (IgG1) and MAb 65 (IgG2a). Our data show that M2e-specific IgG1 requires FcγRIII, whereas IgG2a isotype antibodies protect against influenza A virus challenge via any of the three activating FcγRs.

RESULTS

M2e-specific MAbs 37 and 65 have comparable target specificities and affinities.

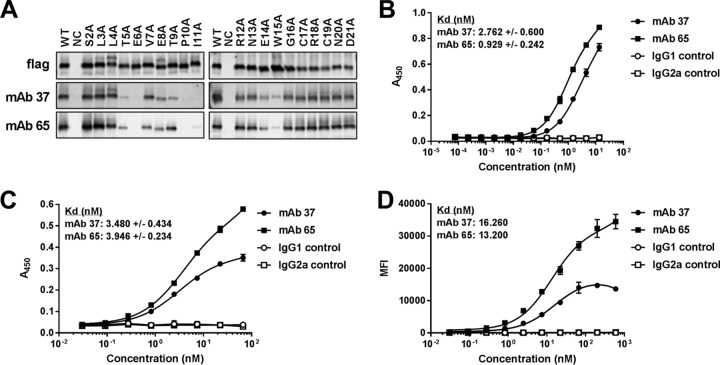

Our aim was to compare the capacity of two M2e-specific monoclonal antibodies that bind a similar epitope with similar affinities but are of a different isotype, to engage FcγRs in vitro and in vivo. For this comparison, we used two M2e-specific monoclonal antibodies: MAb 37 (IgG1) and MAb 65 (IgG2a). Ala scan mutagenesis of M2e revealed that Ala substitutions introduced at positions Thr5, Glu6, Pro10, Ile11, and Trp15 and, to a lesser extent, positions Val7, Glu8, Thr9, and Glu14 affected the recognition of M2 by MAb 37 and MAb 65 (Fig. 1A). The involvement of these amino acid residues in M2e binding is in line with the cocrystal structure of the Fab fragment of MAb 65 with an M2e peptide that we recently reported (17). Next, the affinity of the two MAbs for M2e was determined from surface plasmon resonance measurements, in which the antibodies were immobilized on the surface of a flow cell and M2e peptide was added at different concentrations in solution. This showed that MAb 37 and MAb 65 bound the M2e peptide with similar equilibrium dissociation constants (Kds) (Table 1). We also calculated the affinity for the immobilized M2e peptide by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). However, a higher affinity for MAb 65 (0.929 nM) than for MAb 37 (2.762 nM) was observed using this technique (Fig. 1B). Therefore, the affinity of MAbs 37 and 65 for M2 on virus-infected cells, where M2 assembles as a tetrameric membrane protein, was also determined. MAbs 37 and 65 bound to M2 expressed on the surface of A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) (PR8) virus-infected cells with estimated Kds of 3.480 nM and 3.946 nM, respectively, on the basis of a cellular ELISA (Fig. 1C). The estimated Kd values deduced from flow cytometry analysis of PR8 virus-infected cells for MAbs 37 and 65 were also in the same range: 16.260 nM and 13.200 nM, respectively (Fig. 1D). From the results of these in vitro binding studies, we conclude that the two M2e-specific MAbs bind to the M2e peptide (as determined by surface plasmon resonance) and PR8 virus-infected cells with comparable affinities.

FIG 1.

MAb 37 and MAb 65 recognize a similar epitope in M2e and bind with similar affinities to M2e and M2. (A) Western blot analyses of lysates of HEK293T cells that had been transfected with Flag-tagged M2 wild type (WT) and M2e Ala scan mutants. The blot was probed with anti-Flag MAb, MAb 37, and MAb 65. Lanes: NC, lysate from nontransfected cells; S2A, serine at position 2 in M2e changed to alanine; L3A, leucine at position 3 in M2e changed to alanine, etc. The results shown for the anti-Flag MAb and MAb 65 are republished from reference 17. (B) M2e peptide ELISA using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-purified M2e peptide (SLLTEVETPIRNEWGCRCNDSSD) for coating. Binding of MAb 37 or MAb 65 to M2e-coated wells was determined using a secondary HRP-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody. (C) MDCK cells were infected with A/Puerto Rico/8/34 virus. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were incubated with a dilution series of MAb 37 or MAb 65, followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde and detection by a cellular ELISA. (D) HEK293T cells were infected with A/Puerto Rico/8/34 virus. Sixteen hours later, the cells were incubated with a dilution series of MAb 37 or MAb 65, followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilization, and staining with goat anti-influenza virus RNP polyclonal serum. Binding of MAb 37 and MAb 65 was detected with donkey anti-mouse IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 488, and binding of anti-influenza virus RNP was detected with donkey anti-goat IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 647. The y axis depicts the median fluorescence intensity (MFI), which corresponds to the median fluorescence of binding of MAb 37 or MAb 65 to infected cells from which the median fluorescence of uninfected cells bound by MAb 37 or MAb 65 has been subtracted. The graphs in panels B and C are representative of those from one out of three repeat experiments. Data points represent averages of triplicates (B and C) or duplicates (D), and error bars represent standard deviations. The equilibrium dissociation constants (Kds) of MAb 37 or MAb 65 in panels B and C are averages from three independent experiments, together with their standard deviations.

TABLE 1.

Affinities of anti-M2e antibodies for the M2e consensus sequence measured by surface plasmon resonancea

| Sample | kon (M−1 s−1) | koff (s−1) | Kd (nM) | χ2 (RU2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAb 37 | 3.49 × 105 (6.60 × 102)b | 1.48 × 10−4 (1.70 × 10−6) | 0.423 | 0.123 |

| MAb 65 | 2.24 × 105 (4.70 × 102) | 9.16 × 10−5 (3.50 × 10−6) | 0.409 | 0.0593 |

kon, association rate constant; koff, dissociation rate constant; Kd, equilibrium dissociation constant (koff/kon); χ2, goodness of fit; RU, resonance units.

The data in parentheses represent the standard error calculated on the basis of measurements obtained at seven different peptide concentrations.

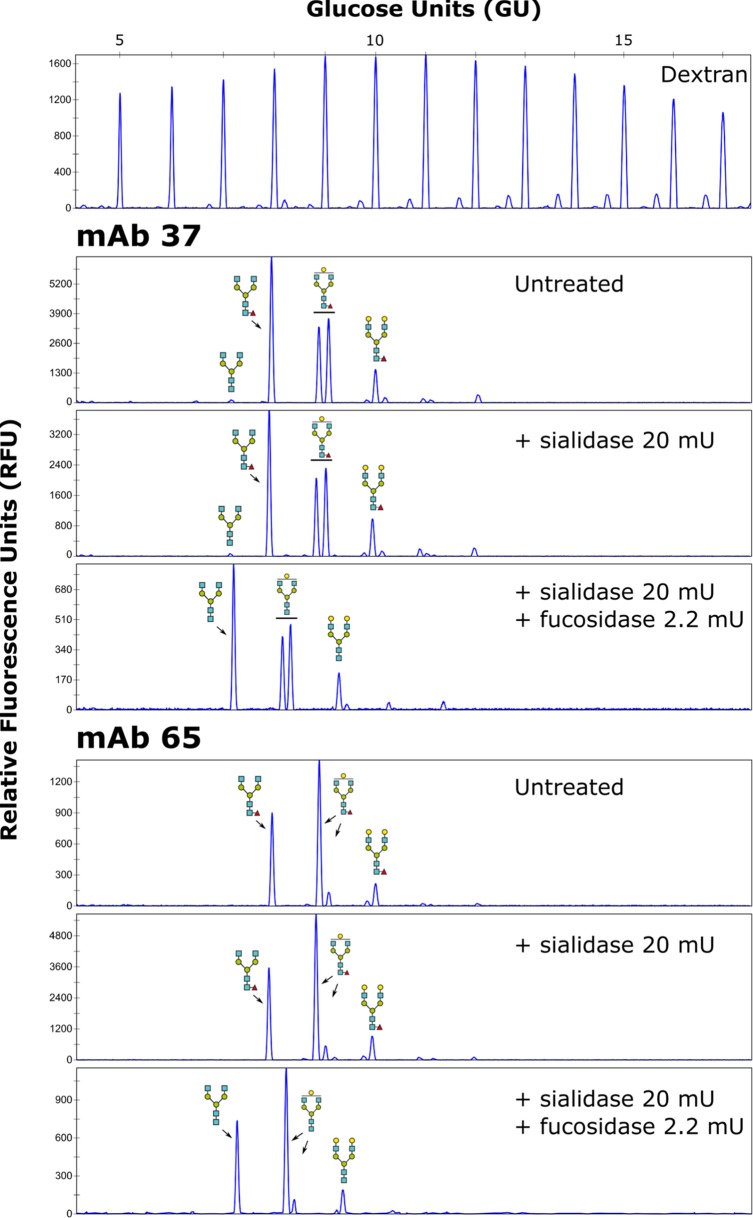

Murine and human IgGs have a conserved N-glycosylation site in their Fc region (18), where the associated N-glycan plays an important role in Fc-dependent effector functions (19). Core fucosylation especially strongly influences the binding of antibodies to FcγRs and the subsequent antibody-mediated cellular cytotoxicity or antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (20–23). We therefore profiled the N-glycans of MAbs 37 and 65 using 8-amino-1,3,6-pyrenetrisulfonic acid (APTS) labeling followed by capillary electrophoresis, using a labeled dextran ladder and N-glycans from bovine RNase B as references (Fig. 2). The two antibodies contained comparable levels of total terminal galactose residues (55.67% for MAb 37 and 65.52% for MAb 65) and were completely core fucosylated (100% for both MAb 37 and MAb 65) (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

N-glycan profiling of MAb 37 and MAb 65. DNA sequencer-assisted fluorophore-assisted capillary electrophoresis chromatograms of the fluorescently labeled dextran ladder (top) and N-glycans on MAb 37 and MAb 65 (bottom). For each MAb, the upper panel provides the chromatogram for the untreated sample, which was subjected to exoglycosidase digests using an α-2,3/6/8-sialidase alone or α-2,3/6/8-sialidase combined with an α-1,2/3/4/6-fucosidase, as indicated. The glucose units from the ladder were annotated using N-glycans from bovine RNase B (not shown), and the annotated structures were confirmed using additional exoglycosidase digests. Blue squares, N-acetylglucosamine residues; green circles, mannose residues; yellow circles, galactose residues; red triangles, fucose residues.

MAbs 37 and 65 differentially activate FcγRs in vitro.

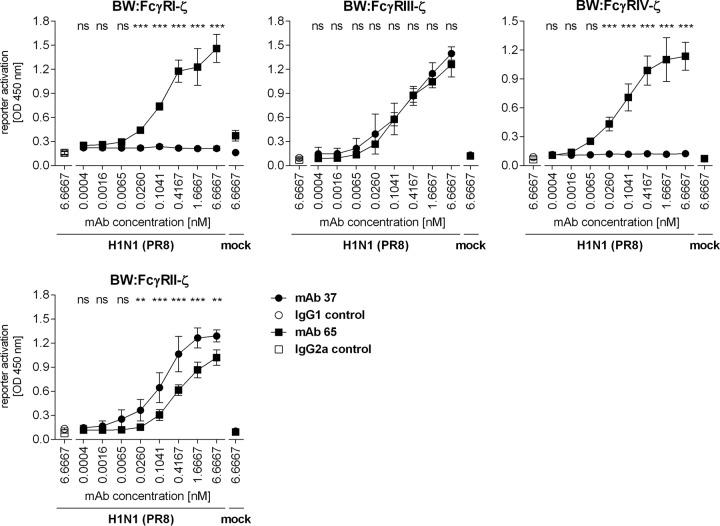

To compare the potencies of MAb 37 and MAb 65 for the activation of individual FcγRs in vitro, a recently developed cell-based activation assay was applied (24, 25). We compared the engagement of individual FcγRs by graded concentrations of MAb 37 and MAb 65 bound to PR8 virus-infected MDCK cells. Control IgG1 and IgG2a monoclonal antibodies did not activate any of the FcγR-ζs in this assay (Fig. 3). IgG2a MAb 65 activated all FcγR-ζs with very similar dose-response curves, ranging from 0.0065 nM MAb to plateau values at 6.7 nM antibody (Fig. 3). In contrast, MAb 37 (IgG1) triggered only the inhibitory FcγRII-ζ and the activating FcγRIII-ζ and completely failed to activate FcγRI and FcγRIV even at very high concentrations of opsonizing MAb. The latter result is in line with the report that monomeric mouse IgG1 binds very poorly to FcγRI and -IV (26). MAbs 37 and 65 activated FcγRIII-ζ equally well, but MAb 37 was approximately 10-fold more potent in activating FcγRII-ζ than MAb 65 (Fig. 3), which accords well with the reported higher affinity of monomeric IgG1 for FcγRII (27). Taken together, MAb 65 and MAb 37 exhibited similar F(ab)2-mediated M2e-binding characteristics and had clearly distinct Fc-mediated functions in vitro.

FIG 3.

MAb 37 and MAb 65 differentially activate FcγRs in vitro. MDCK cells were infected with A/Puerto Rico/8/34 virus (MOI, 5) for 1 h, washed, and cocultured overnight with the FcγR-ζ expression reporter cells and graded concentrations of the anti-M2e MAbs or the corresponding isotype controls. The IL-2 produced was quantified by sandwich ELISA and represents a measure of the magnitude of FcγR activation. Data points are averages from triplicates, and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Two-way ANOVA with the Sidak correction was used for multiple comparisons (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significant). The graphs are representative of those from one out of three repeat experiments. OD, optical density.

Protection by MAb 37 and MAb 65 requires FcγRs.

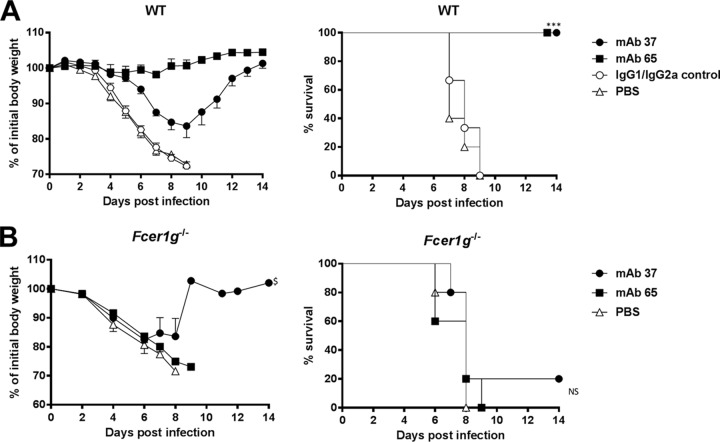

Next, we compared the protective efficacy of passively transferred MAbs 37 and 65 against a potentially lethal influenza A virus challenge (4 50% lethal doses [LD50]) of BALB/c mice with X47 (A/Victoria/3/75 [H3N2] × PR8), a mouse-adapted H3N2 virus (1). Compared to the protection provided by isotype control MAbs, both MAb 37 and MAb 65 protected the animals from lethal infection (Fig. 4A). However, mice that were treated with the M2e-specific IgG2a MAb 65 displayed significantly less body weight loss than M2e-specific IgG1 MAb 37 recipients (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A). This correlated with the lung viral load, since MAb 65 treatment resulted in significantly lower lung viral titers than MAb 37 treatment (P = 0.0004, unpaired t test) (Fig. 5C). The protection provided by MAb 37 and MAb 65 was dose dependent (unpublished result).

FIG 4.

M2e-specific IgG2a protects better than M2e-specific IgG1, and protection depends on FcRγ. (A) M2e-specific IgG2a protects against influenza A virus challenge better than M2e-specific IgG1. Wild-type (WT) BALB/c mice received 5 mg/kg of either MAb 37 (IgG1) or MAb 65 (IgG2a) by intraperitoneal injection. The IgG1/IgG2a control group was treated with 2.5 mg/kg of control IgG1 and 2.5 mg/kg of control IgG2a per mouse. Twenty-four hours later, the mice were challenged with 4 LD50 of mouse-adapted X47 virus. Body weight (left) and survival (right) were monitored for 2 weeks after challenge. In the left-hand graph, data points represent averages, and error bars represent the standard errors of the means. Differences in body weight between the negative-control groups, on the one hand, and the MAb 37- and MAb 65-treated groups, on the other hand, were statistically significant (P < 0.001, REML variance components analysis; n = 6 mice per group on day 0). The differences in body weight curves between groups that received MAb 37 or MAb 65 were statistically significant (P < 0.001, REML variance components analysis). The survival rate of the mice that received MAb 65 or MAb 37 was significantly different from that of mice in the control groups (***, P < 0.001, log-rank test). The results represent those from one out of two repeat experiments, which had similar results. (B) M2e-specific MAbs fail to protect mice lacking the Fc common γ chain. Fcer1g−/− BALB/c mice were treated with 5 mg/kg of MAb 37, MAb 65, or PBS by intraperitoneal injection. Twenty-four hours later, the mice were challenged with 4 LD50 of mouse-adapted X47 virus. Body weight (left) and survival (right) were monitored for 2 weeks after challenge. In the left-hand graph, data points represent averages and error bars represent the standard errors of the means. $, starting from day 9 after infection, data were based on only one surviving mouse. The survival rates of the groups that received MAb 37 or MAb 65 were not significantly different from those for the control groups (P > 0.05, log-rank test; n = 5 mice per group on day 0). NS, not significant.

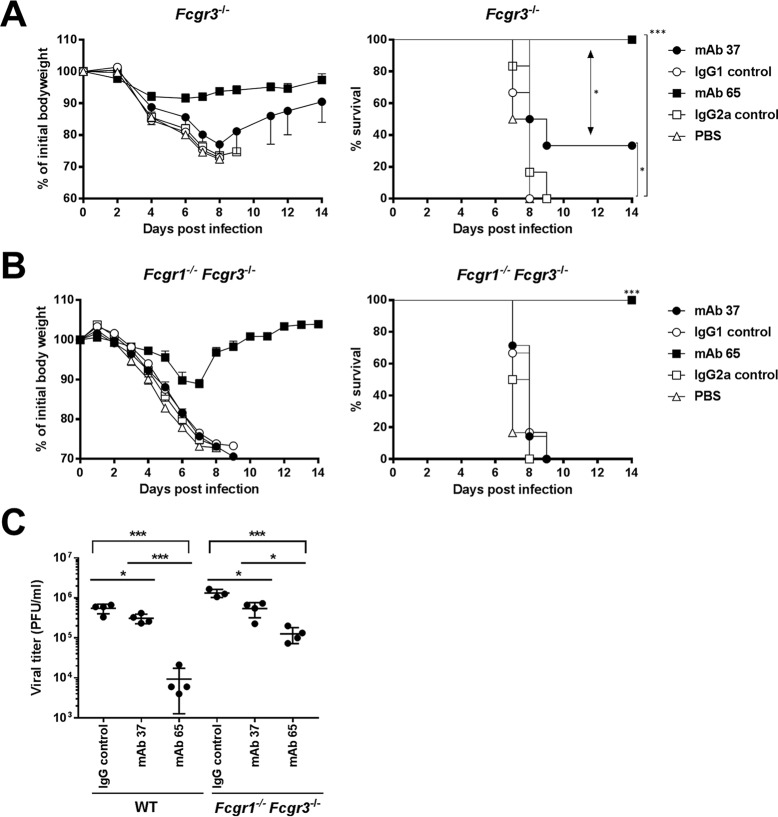

FIG 5.

Protection provided by IgG2a subclass antibodies in the absence of FcγRI and FcγRIII (A) The protection provided by M2e-specific IgG1 MAb depends on FcγRIII. Fcgr3−/− BALB/c mice (n = 6 per group) received 5 mg/kg of MAb 37, MAb 65, negative-control IgG1 or IgG2a MAb, or PBS by intraperitoneal injection. Twenty-four hours later, the mice were challenged with 4 LD50 of mouse-adapted X47 virus and body weight (left) and survival (right) were monitored. In the left-hand graph, data points represent averages and error bars represent the standard errors of the means. The body weight changes of the group that received MAb 65 were significantly different from those of mice that received MAb 37 or control MAbs (P < 0.001, REML variance components analysis). The survival rate of the mice that received MAb 65 was significantly different from that of the mice that received MAb 37 (*, P = 0.0178, log-rank test) and from that of the mice in the control group (***, P < 0.001, log-rank test). The survival rate of the MAb 37 recipient mice was significantly different from that of the mice in the control groups (*, P < 0.05, log-rank test). (B) IgG2a MAb 65 protects against influenza A virus challenge in the absence of FcγRI and -III. Fcgr1−/− Fcgr3−/− BALB/c mice (n = 6 mice per group, except for the MAb 37 group, which had 7 mice) were treated as described in the legend to panel A, and morbidity and mortality were monitored for 2 weeks after challenge. Differences in body weight between the group that received MAb 65 and the group that received MAb 37 were significant (P < 0.001, REML variance components analysis). The survival rate of the group that received MAb 65 was significantly different from that of the group that received MAb 37 and the control group (***, P < 0.001, log-rank test). The graphs are representative of those from one out of two repeat experiments with similar results. (C) Treatment with M2e-specific IgG1 or IgG2a MAb decreases the lung viral load. Wild-type mice (n = 4) or Fcgr1−/− Fcgr3−/− mice (n = 4 mice per group, except for the IgG control group, which had 3 mice) received 5 mg/kg of MAb 37 or MAb 65 or a control IgG mix containing 2.5 mg/kg of IgG1 control MAb and 2.5 mg/kg of IgG2a control MAb. Twenty-four hours later, the mice were challenged with 4 LD50 of mouse-adapted X47 virus, and the lungs were harvested at 6 days postinfection, followed by viral titration by plaque assay using MAb 37. Treatment of wild-type or Fcgr1−/− Fcgr3−/− mice with MAb 37 or MAb 65 resulted in a significant decrease in viral lung titers (P = 0.03 and P = 0.0003, respectively, for BALB/c mice and P = 0.0107 and P = 0.0005, respectively, for mice deficient in Fcgr1 and Fcgr3; P values were determined by an unpaired t test) compared to those in mice receiving the control IgG treatment. The differences in lung viral loads between mice receiving MAb 37 and mice receiving MAb 65 were statistically significant for wild-type BALB/c mice (P = 0.0004, unpaired t test) and mice deficient in Fcgr1 and Fcgr3 (P = 0.0112, unpaired t test). Differences in lung viral loads in mice receiving the IgG control treatment or MAb 65 were statistically significant between wild-type mice and mice deficient in Fcgr1 and Fcgr3 (for IgG control treatment, P = 0.0060; for MAb 37, P = 0.0976; for MAb 65, P = 0.0054; P values were determined by an unpaired t test).

Next, we evaluated the in vivo requirement of FcRγs for protection by the two MAbs. To define the requirement for one or more activating FcγRs for in vivo protection mediated by the two anti-M2e MAbs, we performed passive transfer experiments in Fcer1g−/− mice, which lack the common γ chain and cannot express any functional activating FcγR. At 24 h after antibody administration, the mice were challenged with 4 LD50 of X47. Fcer1g−/− mice that received MAb 65, MAb 37, or the isotype controls showed no significant difference in body weight loss (P = 0.541) (Fig. 4B). Except for one mouse in the MAb 37 recipient group, all Fcer1g−/− mice succumbed to the challenge infection (Fig. 4B), demonstrating that FcγRs are essential for protection against influenza A virus challenge by both M2e-specific MAbs.

MAb 65 can protect in the absence of FcγRI and FcγRIII, and the protection provided by MAb 65 involves FcγRIV.

MAb 37 largely failed to protect Fcgr3−/− mice, although the difference in the survival rates of challenged mice that had been treated with the irrelevant control antibody was significant (P = 0.0289) (Fig. 5A). MAb 65 performed significantly better (P < 0.001) than MAb 37 and completely protected Fcgr3−/− mice from lethal infection and severe morbidity (Fig. 5A). To further narrow down the differential requirement for the activating FcγRs, we performed challenge studies in mice deficient in Fcgr1 and Fcgr3. In these double-deficient mice, MAb 65 provided full protection against virus challenge, whereas all control-treated and MAb 37-treated mice died (Fig. 5B). MAb 65 treatment partially protected against body weight loss after challenge of Fcgr1−/− Fcgr3−/− mice, whereas MAb 37 failed to do so. This difference in protection against morbidity correlated with a significantly lower lung virus load in the Fcgr1−/− Fcgr3−/− mice that had been treated with MAb 65 compared with that in mice that had been treated with MAb 37 (P = 0.0112; unpaired t test) (Fig. 5C).

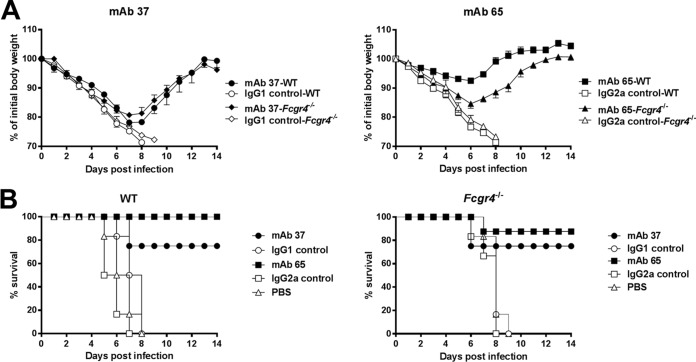

We hypothesized that FcγRIV could be responsible for the protection provided by MAb 65 in the absence of FcγRI and FcγRIII. To test this, wild-type and Fcgr4−/− C57BL/6 mice were treated with MAb 65 or MAb 37 and infected with a lethal dose of X31 (H3N2). Both MAb 37 and MAb 65 protected the mice, whereas control-treated wild-type and Fcgr4−/− C57BL/6 mice did not survive the virus challenge (Fig. 6). Similar to wild-type mice, Fcgr4−/− mice treated with MAb 65 displayed significantly less body weight loss than MAb 37 recipients (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6). The body weight loss after challenge was the same in Fcgr4−/− and wild-type C57BL/6 mice treated with MAb 37 (P = 0.114), in line with a lack of FcγRIV engagement by mouse IgG1 isotype antibodies (Fig. 3 and 6). The protection provided by MAb 65 was partially dependent on FcγRIV, since after infection Fcgr4−/− mice showed a body weight loss significantly different from that for wild-type mice (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6). Taken together, these results suggest that FcγRIV contributes to the protection provided by M2e-specific IgG2a.

FIG 6.

FcγRIV contributes to protection by M2e-specific IgG2a antibodies against influenza A virus challenge. (A) Reduced protection provided by IgG2a MAb 65 in Fcgr4−/− mice. Wild-type or Fcgr4−/− mice were treated with 5 mg/kg of mouse IgG1 MAb 37, IgG2a MAb 65, an isotype control MAb, or PBS 24 h before intranasal infection with 4 LD50 of influenza A virus strain X31. Wild-type and Fcgr4−/− mice were treated with antibody and challenged in parallel in the same experiment. (A) Curves of the body weights of mice treated with MAb 37 (left) or MAb 65 (right); (B) survival curves for mice treated with MAb 37 (left) or MAb 65 (right). Data points represent averages, and error bars represent the standard errors of the means. The data from two independent experiments were pooled. In total, 6 mice were used in the groups treated with PBS and 8 or 9 mice were used in the groups treated with an MAb. The differences in the change in body weight between wild-type and Fcgr4−/− mice that had received MAb 65 prior to challenge were statistically significant (P < 0.001, REML variance components analysis).

DISCUSSION

We isolated and characterized a pair of M2e-specific murine MAbs with similar affinities for M2e and comparable N-glycan profiles of their Fc parts. We compared the potency of activation of individual FcγRs in vitro by this antibody pair in the context of a viral infection and their protective potential in wild-type and FcγR-deficient mice. MAb 65 activated all FcγR-ζs in the presence of influenza A virus-infected cells. In contrast, MAb 37 triggered only the activating FcγRIII-ζ and the inhibitory FcγRII-ζ, with the level of activation of the latter being remarkably higher than that by MAb 65. The two M2e-specific MAbs thus differentially activate FcγRs in vitro. These in vitro results also highlight that FcγRIV can contribute to anti-M2e immune complex recognition on influenza A virus-infected target cells.

The results of in vitro experiments correlated surprisingly well with the results of in vivo experiments in which we compared the protection provided by MAbs 37 and 65 against influenza A virus challenge in mice with different deficiencies in their FcγR compartments. The M2e-specific IgG2a antibody protected better against influenza A virus challenge than the M2e-specific IgG1 antibody, presumably because, as detected in vitro, MAb 65 could engage all three activating receptors, which are expressed on natural killer cells, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages (28, 29). This is in agreement with the finding that active vaccination strategies with M2e fusion constructs that predominantly induce M2e-specific IgG2a/c antibodies result in better protection against challenge (30, 31). In addition, we observed that MAb 65 protected mice from mortality even at a concentration as low as 0.3125 mg/kg of body weight (unpublished result).

In the absence of FcγRIII, the IgG1 MAb largely failed to protect against influenza A virus challenge, while MAb 65 was still protective. Therefore, FcγRIII is not strictly required for MAb 65-mediated protection but significantly contributes to MAb 37-mediated protection. This also suggests that natural killer cells, which in mice express only FcγRIII (28), do not play an indispensable role in the M2e-based immune protection provided by IgG2a isotype antibodies. In the absence of both FcγRI and FcγRIII, mice were still fully protected against death caused by influenza virus challenge. However, Fcgr1−/− Fcgr3−/− mice exhibited significantly more body weight loss than wild-type mice (Fig. 5). The possible contribution of FcγRIV to the protection provided by M2e-specific antibodies has not yet been reported. We observed that Fcgr4−/− mice are protected by MAb 65 but displayed significantly more body weight loss after influenza A virus challenge than wild-type mice. In contrast, MAb 37 protected wild-type and Fcgr4−/− mice equally well, although it performed worse than MAb 65 in terms of weight loss (Fig. 6). These results also accord with the finding that FcγRIV, which is expressed on monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils, plays an important role in IgG2a-dependent effector activities in vivo, including IgG2a-mediated killing of tumor cells (32). Both FcγRI and FcγRIV are expressed on alveolar macrophages, which play an essential role in M2e antibody-mediated immune protection (2, 27, 33, 34). In our model, we found a contribution of FcγRIV but not a determining role for FcγRIV in the protection provided by M2e-specific IgG2a against influenza A virus challenge. Future studies comparing FcγRI-deficient mice and mice lacking all three activating receptors, FcγRI, FcγRIII, and FcγRIV, will be required to determine the relative contribution of the two high-affinity activating Fc receptors FcγRI and FcγRIV.

What are the implications of our findings for the clinical development of M2e-based vaccines? M2e immunity appears to operate in the absence of demonstrable virus-neutralizing activity but, rather, engages Fcγ receptor-expressing myeloid cells. Human IgG1 and IgG3 isotype antibodies can be considered the counterparts of mouse IgG2a antibodies. Therefore, vaccine formulations that promote the induction of antigen-specific IgG1 and IgG3 in humans should be used. The MF59, AS03, and AS04 adjuvants promote such a Th1-specific response (35). Human IgG1 and IgG3 have the highest affinity for FcγRI, which, as in mice, has a broad expression pattern (dendritic cells, monocytes, and macrophages) (27). The sequence of mouse FcγRIV suggests that it is related to human FcγRIIIA (expressed on natural killer cells, monocytes, and macrophages) (26, 34). Therefore, M2e-specific IgG antibodies could possibly provide protection through multiple effector cells that are resident at or recruited to the site of infection.

We still know surprisingly little about how effective antimicrobial vaccines work. It was reported that Fcγ receptor-dependent phagocytosis of influenza A virus virions opsonized with HA-specific antibodies is a strong contributor to the protection provided by a conventional influenza A vaccine (36). In addition, the protection against influenza A virus infection provided by broadly neutralizing antibodies directed against the HA stalk largely depends on FcγRs (16). Recently, another report even suggested that broadly neutralizing anti-influenza virus antibodies that lack hemagglutination inhibition activity require interaction with FcγRs to mediate in vivo protection (37). Therefore, future developments toward antibody-based universal influenza vaccines should consider the role of the Fcγ receptor repertoire in vaccine efficacy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

All animal experiments described in this study were conducted according to national legislation (Belgian laws 14/08/1986 and 22/12/2003, Belgian Royal Decree 06/04/2010) and European legislation (EU Directives 2010/63/EU and 86/609/EEC). All experiments on mice and animal protocols were approved by the ethics committee of Ghent University (permit numbers LA1400091 and EC2012-034).

Monoclonal antibodies and their epitope specificity.

Hybridomas that produce M2e-specific MAbs 37 and 65 were isolated as described previously (17). After subcloning, these two hybridoma cultures were scaled up and MAbs 37 and 65 were purified from the culture supernatant with protein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare). M2e Ala scan analysis was performed as described previously (17), and the results were visualized by Western blotting using MAb 37, MAb 65, or anti-Flag (Sigma-Aldrich) antibody followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (GE Healthcare). Isotype control MAbs directed against the hepatitis B virus core (IgG1) or the small hydrophobic protein of human respiratory syncytial virus (IgG2a) were produced and purified as described above.

Affinity measurement by ELISA and flow cytometry.

The affinity of MAb 37 and MAb 65 for M2e was determined by ELISA with an M2e peptide (SLLTEVETPIRNEWGCRCNDSSDSG, used at 2 μg/ml in 50 μl/well), as described in reference 17, or MDCK cells infected with A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) (PR8). A dilution series of MAb 65 or MAb 37 was applied to infected cells on ice. Subsequently, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and antibody binding was detected using HRP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (GE Healthcare).

For flow cytometry analysis, PR8 virus-infected human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells were incubated on ice with a dilution series of MAb 65 or MAb 37 in 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and subsequently fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). After permeabilization (10× permeabilization buffer diluted in double-distilled water; eBioscience), cells were stained with 1/2,000-diluted polyclonal goat anti-influenza virus ribonucleoprotein (RNP; catalog number NR-4282; Biodefense and Emerging Infections Resources Repository, NIAID, NIH). Binding of primary antibodies was revealed with donkey anti-mouse IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 (1/600; Invitrogen) and donkey anti-goat IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 647 (1/600; Invitrogen). The median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the cells was determined with an LSRII HTS flow cytometer (BD). The influenza virus-specific MFI was calculated by subtracting the MFI of MAb 37- or MAb 65-positive cells in the RNP-negative population (uninfected HEK293T cells stained with 10 μg/ml MAb 37 or MAb 65 and anti-RNP) from the MFI of MAb 37- or MAb 65-positive cells in the RNP-positive population (infected HEK293T cells stained with a dilution series of MAb 37 or MAb 65 and RNP).

Affinity measurement by surface plasmon resonance.

The affinities of MAbs 37 and 65 for the M2e peptide were determined using a Biacore T200 instrument (GE Healthcare). Anti-M2e MAbs were immobilized on the flow cells of a CM5 sensor chip (GE Healthcare) by amine coupling according to the manufacturer's instructions. A flow cell blocked with ethanolamine served as a reference. The M2e peptide in HBS-EP buffer (0.01 M HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.005% [vol/vol] surfactant P20) was added at concentrations of 0.39, 0.78, 3.13, 6.25, 12.5, 25, and 50 nM. The samples were injected at 50 μl/min for 180 s, after which dissociation was monitored for 1,000 s. The sensor chip surface was regenerated by injecting 10 mM HCl for 60 s and 20 mM HCl for another 60 s. Biacore T200 evaluation software (v1.0) was used to calculate the association rate constant (kon), the dissociation rate constant (koff), and the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd; which is equal to koff/kon) by fitting a 1:1 binding model with a drifting baseline.

N-glycan analysis.

N-linked oligosaccharides were isolated, derivatized with APTS, and analyzed by capillary electrophoresis on an ABI 3130 capillary DNA sequencer using in-house-produced peptide-N-glycosidase F (15.4 mU/μl) as described previously (38). As electrophoretic mobility references, a labeled dextran ladder and N-glycans from bovine RNase B were included. The data were analyzed using GeneMapper software (Applied Biosystems), and N-glycan profiles were exported as scalable vector graphics (svg) for manual alignment and annotation in Inkscape software (v0.91). Exoglycosidase treatments to determine the degree of fucosylation on labeled glycans were carried out overnight at 37°C in 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.0) using 20 mU Arthrobacter ureafaciens α-2,3/6/8-sialidase (produced in-house), 2.2 mU α-1,2/3/4/6-fucosidase from bovine kidney (Prozyme), or both.

In vitro FcγR activation assay.

FcγR activation by MAbs 37 and 65 was compared using a recently developed in vitro FcγR activation assay (24, 25). Cloning of FcγR-ζ constructs and the generation of FcγR-ζ BW5147 reporter cells were performed as reported previously (24, 25). Activation of stably transduced FcγR-ζ BW5147 reporter cells by immune complexes results in the production of interleukin-2 (IL-2), which was quantified by ELISA (24, 25). Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were seeded in 96-well flat-bottom plates and infected with PR8 virus (multiplicity of infection [MOI], 5). After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, unbound virus particles were removed by washing, and serial dilutions of the MAbs were added, followed by the addition of 1.5 × 105 FcγR-ζ BW5147 reporter cells in a total volume of 200 μl RPMI with 10% fetal calf serum per well. Cocultures were incubated overnight at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. To increase the release of produced IL-2 from reporter cells, 100 μl PBS with 0.1% Tween was added to each well, and 150 μl from each well was used in an anti-IL-2 sandwich ELISA as described previously (24, 25).

Challenge experiments in mice.

BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan (The Netherlands) or Charles River (France); Fcer1g−/− BALB/c mice, which lack the common γ chain and, consequently, the ability to express all activating FcγRs, were purchased from Taconic (Denmark); and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River (France). Fcgr3−/− BALB/c mice, Fcgr1−/− Fcgr3−/− BALB/c mice, and Fcgr4−/− C57BL/6 mice were bred in-house under specific-pathogen-free (SPF) conditions. Mice were used at the age of 7 to 8 weeks and were housed in individually ventilated cages in a temperature-controlled environment with 12-h light and 12-h dark cycles and food and water ad libitum. To evaluate protection, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 5 mg/kg of MAb 37 or MAb 65 (unless otherwise stated) or negative-control MAbs. Twenty-four hours later, the mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (10 mg/kg) and xylazine (60 mg/kg) and challenged by intranasal administration of 50 μl PBS containing 4 LD50 of mouse-adapted X47 (A/Victoria/3/75 [H3N2] × PR8) influenza A virus for wild-type BALB/c, Fcer1g−/− BALB/c, Fcgr3−/− BALB/c, and Fcgr1−/− Fcgr3−/− BALB/c mice. Four LD50 of mouse-adapted X31 (A/Aichi/2/68 [H3N2] × PR8) influenza A virus was used to challenge wild-type C57BL/6 and Fcgr4−/− C57BL/6 mice. C57BL/6 mice were challenged with X31 because the LD50 of this virus was established for this mouse strain. However, X31 and X47 have an identical gene segment 7. The body weights and rates of survival of the mice were monitored for 2 weeks after challenge, and animals that had lost more than 25% of their body weight compared to that at the time of challenge were euthanized. To determine the effect of MAb 37 and MAb 65 treatment on lung viral load, complete lungs were harvested at 6 days postinfection and homogenized in 1 ml of PBS using metal beads, followed by 5 min of centrifugation at 450 × g. The supernatants were stored at −80°C. The lung viral titer was determined using a plaque assay, where plaques were stained with MAb 37, followed by secondary anti-mouse IgG HRP-linked antibody (GE Healthcare) and visualization using TrueBlue peroxidase substrate (KPL).

Statistics.

The statistical significance of the difference in the results obtained with the different MAbs in the FcγR activation assay was analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis of the differences in survival rates was performed by comparing Kaplan-Meier curves using the log-rank test. Statistical analysis of the differences in lung viral titers was performed using the unpaired t test. These tests were performed in GraphPad Prism (v6.07) software for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Statistical comparison of the differences in body weight loss was performed using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) variance components analysis in Genstat software (64 bit, v18.1). The following linear mixed model (random terms are underlined) was fitted to most of the data: Yijkt = μ + genotypej + treatmentk + timet + (genotype.treatment)jk + (genotype.time)jt + (treatment.time)kt +(genotype.treatment.time)jkt + (mouse.time)it + residualijkt, where Yijkt is the relative body weight of the ith mouse with genotype j treated with k for which the results were measured at time point t (where t is equal to 1 to 14 days, equally spaced), and μ is the overall mean calculated for all mice considered across all time points. To compare the morbidity of wild-type BALB/c mice and Fcgr1−/− Fcgr3−/− BALB/c mice after MAb 65 treatment, the following model was fitted: Yijkt = μ + genotypej + timet + (genotype.time)jt + residualijt, where Yijt is the relative body weight of the ith mouse with genotype j for which the results were measured at time point t (where t is equal to 1 to 14 days, equally spaced), and μ is the overall mean calculated for all mice considered across all time points. A first-order autoregressive covariance structure was used to model the within-subject correlation and allowed heterogeneity across time. The significance of the fixed main and interaction effects was assessed by an F test. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Sjef Verbeek (Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands) for providing Fcgr3−/− and Fcgr1−/− Fcgr3−/− BALB/c mice and to Helmut Hanenberg (Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) for providing lentiviral plasmids. We thank Marnik Vuylsteke for performing the statistical analysis. We thank Frederik Vervalle for excellent technical assistance and Céline Steyt for animal care. We thank Jan Spitaels for help with the flow cytometric analysis.

We declare no competing financial interests.

This work was supported by the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (project grant G052412N), the Ghent University Industrial Research Fund (IOF08/STEP/001), and the Ghent University Special Research Fund (project BOF12/GOA/014) to X.S. S.V.D.H. is a Ph.D. fellow and B.S. a postdoctoral fellow at the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek. L.D. was supported by the State Scholarship Fund (file no. 2011674067) from the China Scholarship Council and by IUAP-BELVIR p7/45. A.K. is supported by FP7 ITN UniVacFlu, and K.R. is supported by FP7 Collaborative Project FLUNIVAC. K.E. was supported by the Graduate School Molecules of Infection, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf.

REFERENCES

- 1.Neirynck S, Deroo T, Saelens X, Vanlandschoot P, Jou WM, Fiers W. 1999. A universal influenza A vaccine based on the extracellular domain of the M2 protein. Nat Med 5:1157–1163. doi: 10.1038/13484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El Bakkouri K, Descamps F, De Filette M, Smet A, Festjens E, Birkett A, Van Rooijen N, Verbeek S, Fiers W, Saelens X. 2011. Universal vaccine based on ectodomain of matrix protein 2 of influenza A: Fc receptors and alveolar macrophages mediate protection. J Immunol 186:1022–1031. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Treanor JJ, Tierney EL, Zebedee SL, Lamb RA, Murphy BR. 1990. Passively transferred monoclonal antibody to the M2 protein inhibits influenza A virus replication in mice. J Virol 64:1375–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamb RA, Zebedee SL, Richardson CD. 1985. Influenza virus-M2 protein is an integral membrane-protein expressed on the infected-cell surface. Cell 40:627–633. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zebedee SL, Lamb RA. 1988. Influenza A virus M2 protein: monoclonal antibody restriction of virus growth and detection of M2 in virions. J Virol 62:2762–2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng J, Zhang M, Mozdzanowska K, Zharikova D, Hoff H, Wunner W, Couch RB, Gerhard W. 2006. Influenza A virus infection engenders a poor antibody response against the ectodomain of matrix protein 2. Virol J 3:102. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-3-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhong W, Reed C, Blair PJ, Katz JM, Hancock K. 2014. Serum antibody response to matrix protein 2 following natural infection with 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus in humans. J Infect Dis 209:986–994. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Filette M, Martens W, Roose K, Deroo T, Vervalle F, Bentahir M, Vandekerckhove J, Fiers W, Saelens X. 2008. An influenza A vaccine based on tetrameric ectodomain of matrix protein 2. J Biol Chem 283:11382–11387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800650200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan J, Liang X, Horton MS, Perry HC, Citron MP, Heidecker GJ, Fu TM, Joyce J, Przysiecki CT, Keller PM, Garsky VM, Ionescu R, Rippeon Y, Shi L, Chastain MA, Condra JH, Davies ME, Liao J, Emini EA, Shiver JW. 2004. Preclinical study of influenza virus A M2 peptide conjugate vaccines in mice, ferrets, and rhesus monkeys. Vaccine 22:2993–3003. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jegerlehner A, Schmitz N, Storni T, Bachmann MF. 2004. Influenza A vaccine based on the extracellular domain of M2: weak protection mediated via antibody-dependent NK cell activity. J Immunol 172:5598–5605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schotsaert M, De Filette M, Fiers W, Saelens X. 2009. Universal M2 ectodomain-based influenza A vaccines: preclinical and clinical developments. Expert Rev Vaccines 8:499–508. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang BZ, Gill HS, Kang SM, Wang L, Wang YC, Vassilieva EV, Compans RW. 2012. Enhanced influenza virus-like particle vaccines containing the extracellular domain of matrix protein 2 and a Toll-like receptor ligand. Clin Vaccine Immunol 19:1119–1125. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00153-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turley CB, Rupp RE, Johnson C, Taylor DN, Wolfson J, Tussey L, Kavita U, Stanberry L, Shaw A. 2011. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant M2e-flagellin influenza vaccine (STF2.4xM2e) in healthy adults. Vaccine 29:5145–5152. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang R, Song A, Levin J, Dennis D, Zhang NJ, Yoshida H, Koriazova L, Madura L, Shapiro L, Matsumoto A, Mikayama T, Kubo RT, Sarawar S, Cheroutre H, Kato S. 2008. Therapeutic potential of a fully human monoclonal antibody against influenza A virus M2 protein. Antiviral Res 80:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmitz N, Beerli RR, Bauer M, Jegerlehner A, Dietmeier K, Maudrich M, Pumpens P, Saudan P, Bachmann MF. 2012. Universal vaccine against influenza virus: linking TLR signaling to anti-viral protection. Eur J Immunol 42:863–869. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiLillo DJ, Tan GS, Palese P, Ravetch JV. 2014. Broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies require FcgammaR interactions for protection against influenza virus in vivo. Nat Med 20:143–151. doi: 10.1038/nm.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho KJ, Schepens B, Seok JH, Kim S, Roose K, Lee JH, Gallardo R, Van Hamme E, Schymkowitz J, Rousseau F, Fiers W, Saelens X, Kim KH. 2015. Structure of the extracellular domain of matrix protein 2 of influenza A virus in complex with a protective monoclonal antibody. J Virol 89:3700–3711. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02576-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krapp S, Mimura Y, Jefferis R, Huber R, Sondermann P. 2003. Structural analysis of human IgG-Fc glycoforms reveals a correlation between glycosylation and structural integrity. J Mol Biol 325:979–989. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jefferis R, Lund J, Pound JD. 1998. IgG-Fc-mediated effector functions: molecular definition of interaction sites for effector ligands and the role of glycosylation. Immunol Rev 163:59–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1998.tb01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forthal DN, Gach JS, Landucci G, Jez J, Strasser R, Kunert R, Steinkellner H. 2010. Fc-glycosylation influences Fcgamma receptor binding and cell-mediated anti-HIV activity of monoclonal antibody 2G12. J Immunol 185:6876–6882. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herter S, Birk MC, Klein C, Gerdes C, Umana P, Bacac M. 2014. Glycoengineering of therapeutic antibodies enhances monocyte/macrophage-mediated phagocytosis and cytotoxicity. J Immunol 192:2252–2260. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shields RL, Lai J, Keck R, O'Connell LY, Hong K, Meng YG, Weikert SH, Presta LG. 2002. Lack of fucose on human IgG1 N-linked oligosaccharide improves binding to human Fcgamma RIII and antibody-dependent cellular toxicity. J Biol Chem 277:26733–26740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shinkawa T, Nakamura K, Yamane N, Shoji-Hosaka E, Kanda Y, Sakurada M, Uchida K, Anazawa H, Satoh M, Yamasaki M, Hanai N, Shitara K. 2003. The absence of fucose but not the presence of galactose or bisecting N-acetylglucosamine of human IgG1 complex-type oligosaccharides shows the critical role of enhancing antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem 278:3466–3473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210665200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corrales-Aguilar E, Trilling M, Hunold K, Fiedler M, Le VT, Reinhard H, Ehrhardt K, Merce-Maldonado E, Aliyev E, Zimmermann A, Johnson DC, Hengel H. 2014. Human cytomegalovirus Fcgamma binding proteins gp34 and gp68 antagonize Fcgamma receptors I, II and III. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004131. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corrales-Aguilar E, Trilling M, Reinhard H, Merce-Maldonado E, Widera M, Schaal H, Zimmermann A, Mandelboim O, Hengel H. 2013. A novel assay for detecting virus-specific antibodies triggering activation of Fcgamma receptors. J Immunol Methods 387:21–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nimmerjahn F, Bruhns P, Horiuchi K, Ravetch JV. 2005. FcgammaRIV: a novel FcR with distinct IgG subclass specificity. Immunity 23:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guilliams M, Bruhns P, Saeys Y, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. 2014. The function of Fcgamma receptors in dendritic cells and macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol 14:94–108. doi: 10.1038/nri3582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruhns P. 2012. Properties of mouse and human IgG receptors and their contribution to disease models. Blood 119:5640–5649. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-380121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. 2011. FcgammaRs in health and disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 350:105–125. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ibanez LI, Roose K, De Filette M, Schotsaert M, De Sloovere J, Roels S, Pollard C, Schepens B, Grooten J, Fiers W, Saelens X. 2013. M2e-displaying virus-like particles with associated RNA promote T helper 1 type adaptive immunity against influenza A. PLoS One 8:e59081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song JM, Van Rooijen N, Bozja J, Compans RW, Kang SM. 2011. Vaccination inducing broad and improved cross protection against multiple subtypes of influenza A virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:757–761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012199108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nimmerjahn F, Lux A, Albert H, Woigk M, Lehmann C, Dudziak D, Smith P, Ravetch JV. 2010. FcgammaRIV deletion reveals its central role for IgG2a and IgG2b activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:19396–19401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014515107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee SM, Gardy JL, Cheung CY, Cheung TK, Hui KP, Ip NY, Guan Y, Hancock RE, Peiris JS. 2009. Systems-level comparison of host-responses elicited by avian H5N1 and seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses in primary human macrophages. PLoS One 4:e8072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mancardi DA, Iannascoli B, Hoos S, England P, Daeron M, Bruhns P. 2008. FcgammaRIV is a mouse IgE receptor that resembles macrophage FcepsilonRI in humans and promotes IgE-induced lung inflammation. J Clin Invest 118:3738–3750. doi: 10.1172/JCI36452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coffman RL, Sher A, Seder RA. 2010. Vaccine adjuvants: putting innate immunity to work. Immunity 33:492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huber VC, Lynch JM, Bucher DJ, Le J, Metzger DW. 2001. Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis makes a significant contribution to clearance of influenza virus infections. J Immunol 166:7381–7388. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DiLillo DJ, Palese P, Wilson PC, Ravetch JV. 2016. Broadly neutralizing anti-influenza antibodies require Fc receptor engagement for in vivo protection. J Clin Invest 126:605–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI84428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laroy W, Contreras R, Callewaert N. 2006. Glycome mapping on DNA sequencing equipment. Nat Protoc 1:397–405. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]