Abstract

Approximately 3.6 million individuals suffer from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the western world, with an annual global incidence rate of 3–20 cases/100,000 individuals. The etiology of IBD is unknown, and the currently available treatment options are not satifactory for long-term treatment. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease present with abnormalities in multiple intestinal endocrine cell types, and a number of studies have suggested that interactions between gut hormones and immune cells may serve a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of IBD. The aim of the present study was to investigate alterations in colonic endocrine cells in a rat model of IBD. A total of 30 male Wistar rats were divided into control and trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis groups. Colonoscopies were performed in the control and TNBS groups at day 3 following the induction of colitis, and colonic tissues were collected from all animals. Colonic endocrine and immune cells in the obtained tissue samples were immunostained and their densities were quantified. The densities of chromogranin A, peptide YY, and pancreatic polypeptide-producing cells were significantly lower in the TNBS group compared with the control group, whereas the densities of serotonin, oxyntomodulin, and somatostatin-producing cells were significantly higher in the TNBS group. The densities of mucosal leukocytes, B/T-lymphocytes, T-lymphocytes, B-lymphocytes, macrophages/monocytes and mast cells were significantly higher in the TNBS group compared with the controls, and these differences were strongly correlated with alterations in all endocrine cell types. In conclusion, the results suggest the presence of interactions between intestinal hormones and immune cells.

Keywords: chromogranin A, endocrine cells, inflammatory bowel disease, immune cells, oxyntomodulin, pancreatic polypeptide, peptide YY, serotonin, somatostatin, trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis

Introduction

Abnormalities in several intestinal endocrine cell types have been reported in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and in animal models of human IBD (1–20). The association between the neuroendocrine peptides/amines in the gut and the immune system has been previously investigated, and it was suggested that interactions between gut hormones and immune cells may serve a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of IBD (8,10,11,21–29).

The etiology of IBD is unknown and the currently available treatments are not completely satisfactory (2,30). Treatment with 5-aminosalicylates and corticosteroids are not effective for the long-term treatment of the majority of patients with IBD. In addition, thiopurine analogues, mercaptopurine and azathioprine, as well as methotrexate, have been used. Short and long-term side effects limit the use of these agents. Biological agents, such as antibodies against tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), have been used for two decades. However, only ~65% of patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease respond to treatment with anti-TNFα, and surgery remains the only option for many IBD patients (2,30). Understanding the role of the gut neuroendocrine peptides/amines in the pathophysiology of IBD may provide an insight into its etiology and lead to the use of agonists or antagonists to these peptides and amines as a treatment for IBD (26).

Using a model of human ulcerative colitis (UC) in dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced rats, a recent study demonstrated that abnormalities in the large intestine endocrine cells were strongly correlated with the alterations in immune cells (31). The present study investigated the large intestine endocrine cells in an animal model of Crohn's disease (CD), which involved the induction of colitis in rats using trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS). The aim of the current study was to determine whether a change in immune cell number is correlated with abnormalities in the endocrine cells.

Materials and methods

Animal model

A total of 30 male Wistar rats (6 weeks of age; Wistar Hannover GALAS; Taconic Biosciences, Inc., Lille Skensved, Denmark), with a mean body weight of 276 g (range, 235–380 g), were housed in Makrolon III cages with water and food available ad libitum. They were fed a standard diet (B&K Universal AS, Nittedal, Norway) and were maintained at a temperature of 20–22°C, a relative humidity of 50–60% and under 12 h light/dark cycles. Rats were acclimated to these animal house conditions for a minimum of 7 days prior to the start of the experiments. They were then divided equally into the following 2 groups: Control and TNBS-induced colitis.

Induction of colitis with TNBS

Rats were fasted for 24 h prior to TNBS administration. A single dose of TNBS (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) was administered to the colon of each rat (25 mg/animal in a 50% ethanol solution; 0.5 ml/rat) followed by 2 ml air, at 8 cm from the anal margin using an 8.5 cm-long, 2.5-mm-wide round-tipped Teflon feeding tube (AgnTho's AB, Lidingö, Sweden) under isoflurane (Schering-Plough Pharmaceuticals, North Wales, USA) anesthesia. The animals were kept in a prone position with their hind legs raised for at least 2 min following the administration of the TNBS. They were supervised until recovery and then monitored several times daily. The control group received the same treatment as the TNBS group, except that 0.9% saline instead of TNBS was introduced into the colon. Any rats that exhibited signs of pain were injected subcutaneously with 1 ml Temgesic (0.3 mg Temgesic/ml; Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Hoddesdon, UK).

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopies were performed in the control and TNBS rats at 3 days following the administration of 0.9% saline and TNBS, respectively. The bowels were prepared as described previously (32). Briefly, prior to the colonoscopy, the rats were deprived of food for 24 h and received gastric doses of 1 and 2 ml Picoprep (Ferring Holding SA, Saint Prex, Switzerland) followed by 2 ml water at 24 and 12 h, respectively. Picoprep was administered using an 8.5 cm-long, 2.5 mm wide round-tipped Teflon feeding tube (AgnTho's AB). Picoprep (150 ml) contains 10 mg sodium sulfates, 3.5 g magnesium oxide, and 12 g citric acid.

Rats were anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane (Merck Sharpe & Dohme) prior to and during the colonoscopy. They were placed in a supine position and secured to an acrylic surgical table (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA), and a warming pad (T/Pad; Gaymar Industries, Inc., Orchard Park, NY, USA) with a heat therapy pump (Gaymar TP500 T/Pump; Gaymar Industries, Inc.) was used to maintain normothermia during the procedure. The top of a video gastroscope (GIF-N180; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was lubricated with 2% lidocaine (Xylocaine; AstraZeneca, Södertälje, Sweden) and introduced gently into the anus.

Endoscopic inflammation was scored according to the same grading scale as described by Vermeulen et al (33). This scale comprises the following five subscales (total score, 0–19 points): Degree of inflammation (0–6 points), extent of disease (0–10 points), stenosis (0 or 1 point), edema (0 or 1 point) and active bleeding (0 or 1 point).

Following the procedure, rats were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation and a postmortem laparotomy was conducted. Tissue samples obtained from the distal colon were examined histopathologically, and with immunostaining techniques as described below.

The local ethical committee for experimental animals at the University of Bergen (Bergen, Norway), which is responsible for implementing the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes, approved the protocols employed for the purposes of the current study.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis

Rat colon tissue samples were fixed overnight in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at into 5 µm-sections. The sections were deparaffinized and then stained with hematoxylin-eosin, or immunostained using the ultraView Universal DAB Detection kit (version 1.02.0018; Venata Medical Systems, Inc., Basel, Switzerland) and the BenchMark Ultra IHC/ISH staining module (Venata Medical Systems, Inc.). Tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies for 32 min at 37°C. Details of the primary antibodies used are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Details of primary antibodies used.

| Target protein | Species raised in | Target species | Dilution | Source | Catalogue number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromogranin A | Mousea | N-terminal of purified chromograninA | 1:1,000 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | M869 |

| Serotonin | Mousea | Serotonin | 1:1,500 | Dako | 5HT-209 |

| Peptide YY | Rabbitb | Peptide YY | 1:1,600 | Alpha-Diagnostics International (San Antonio, TX, USA) | PYY 11A |

| Oxyntomodulin | Rabbitb | Porcine glucagon | 1:200 | Acris Antibodies GmbH (Herford, Germany) | BP508 |

| Pancreatic | Rabbitb | Synthetic human polypeptide polypeptide | 1:500 | Diagnostic Bio-Systems (Pleasanton CA, USA) | 114 |

| Somatostatin | Rabbitb | Synthetic human somatostatin | 1:800 | Dako | A566 |

| Leukocytes | Mousea | Human CD45 | 1:600 | Dako | M0701 |

| B/T lymphocytes | Mousea | Human CD5 | 1:500 | Dako | IS082 |

| T lymphocytes | Mousea | Human CD57 | 1:200 | Dako | IS647 |

| B lymphocytes | Mousea | Human CD23 | 1:400 | Dako | IS781 |

| Monocytes and macrophages | Mousea | Human CD68 | 1:100 | Dako | M0814 |

| Mast cells | Mousea | Human mast cell tryptase | 1:800 | Dako | M7052 |

denote monoclonal and polyclonal primary antibodies, respectively.

Quantification of endocrine and immune cells

The endocrine and immune cells were quantified by manually counting each cell type in 10 randomly selected microscopic fields of view using cellSens imaging software (version 1.7; cellSens; Olympus Corporation). The number of endocrine cells in the lining epithelium, and the number of immune cells in the lamina propria were manually counted in each field using a computer mouse. To achieve this, the epithelial cell area was determined by manually drawing an enclosed region with the computer mouse. A ×40 objective was used, which, represented a tissue area of 0.035 mm2 for each frame (field) on the monitor. The data are presented as the number of endocrine cells/mm2 of epithelium, and the number of immune cells/field of view. Immunostained sections were coded and mixed, and measurements were determined by the same person (Professor Magdy El-Salhy), who was unaware of which group the slides were derived from.

Statistical analysis

Differences between the control and TNBS groups were analyzed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. The existence of a correlation between abnormalities/alterations in the densities of endocrine cells and immune cells was determined using the nonparametric Spearman's rank correlation test. The data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Histopathological examination

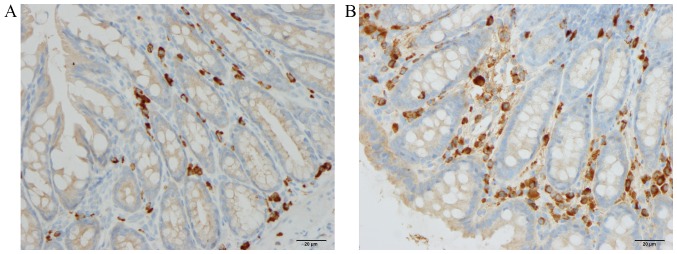

Histopathological examination of the colonic tissues demonstrated that those derived from control rats displayed a normal histology, whereas those from the TNBS group exhibited an abnormal mucosal architecture, the presence of crypt abscesses, edema, bleeding and infiltration of immune cells into the mucosa and submucosa (Fig. 1).

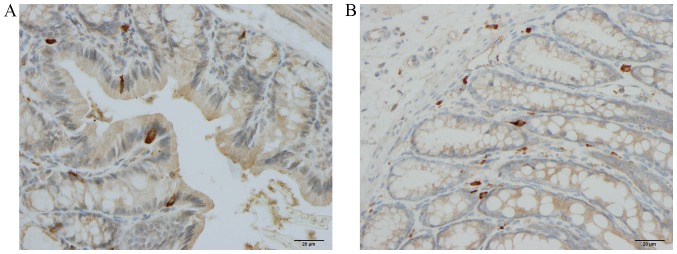

Figure 1.

Identification of macrophages/monocytes in the lamina propria of the colon derived from (A) a control rat (B) a rat with trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis.

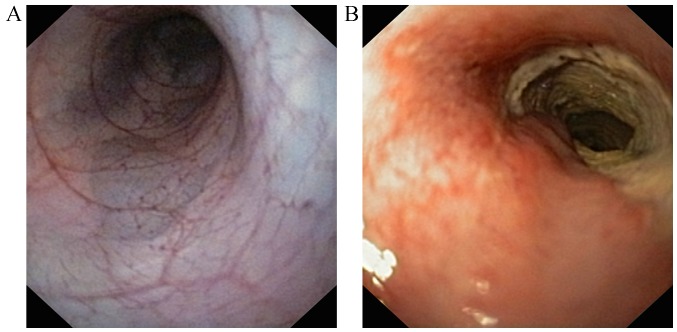

Colonoscopy

Rat colons in the control group displayed a normal appearance with undamaged mucosa and clear branching of blood vessels, whereas the colonic mucosa in the TNBS group exhibited patchy and discontinuous erythema, edema and occasional hemorrhage (Fig. 2). In addition, aphthoid ulcers abruptly surrounded by normal mucosa were observed in the colons of TNBS rats (Fig. 2B). The deep ulcerations coalesced, which led to mucosal detachment and the presence of few mucosal islands. Ulcerated stenosis was also observed in TNBS rat colons (Fig. 2B). The endoscopic inflammation scores were 0 and 6.4±0.8 in the control and TNBS groups, respectively.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic appearance of the colon in (A) a normal control rat and (B) a rat with trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis, demonstrating mucosal erythema, edema and ulcerated stenosis.

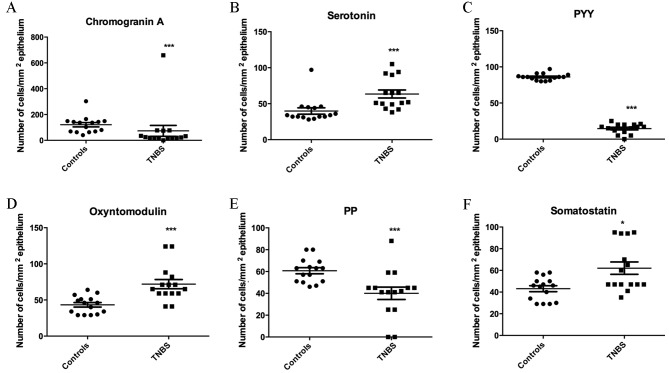

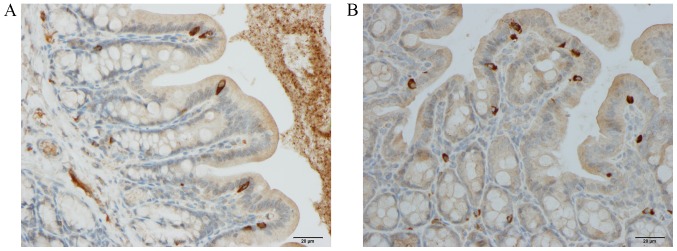

Endocrine cells

The densities of various endocrine cells are presented in Figs. 3, 4 and 5. The density of chromogranin A (CgA), peptide YY (PYY) and pancreatic polypeptide (PP) staining was reduced in the colon tissues from rats in the TNBS group compared with those of the control group (P<0.0001, P<0.0001 and P=0.0002, respectively; Fig. 3). In contrast, serotonin oxyntomodulin and somatostatin densities were increased in the colon tissues from the TNBS group compared with those of the controls (P<0.0001, P<0.0001 and P=0.01, respectively; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Densities of (A) chromogranin A, (B) serotonin, (C) PYY, (D) oxyntomodulin, (E) PP and (F) somatostatin in the colon tissues derived from normal controls and those from TNBS-induced colitis. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 vs. controls. TNBS, trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid; PYY, peptide YY; PP, pancreatic polypeptide.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining of serotonin in the colon tissues derived form (A) a control rat and (B) a rat with trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical staining of peptide YY in the colon tissues derived from (A) a control rat and (B) a rat with trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis.

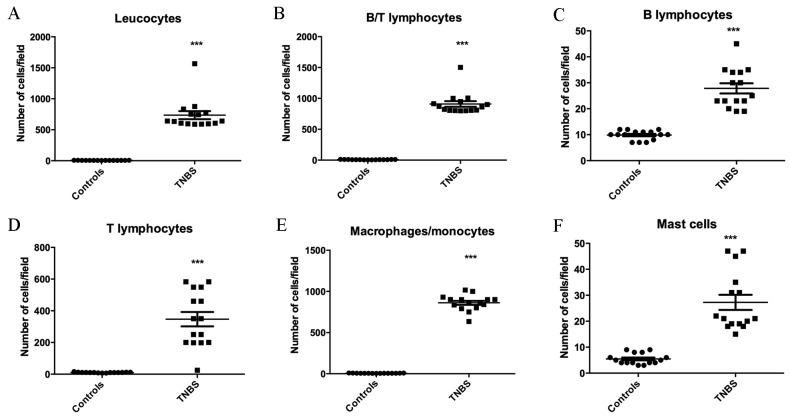

Immune cells

As presented in Figs. 1 and 6, the densities of all types of immune cells were significantly greater in the TNBS group compared with the control group [leukocytes, 5.9±0.4 vs. 23.3±2.2 cells/field (P<0.0001); B/T lymphocytes, 9.0±0.7 vs. 35.8±2.3 cells/field (P<0.0001); T lymphocytes, 10.5±0.6 vs. 26.6±2.9 cells/field (P<0.0001); B lymphocytes, 9.7±0.4 vs. 27.7±2.6 cells/field (P<0.0001); macrophages/monocytes, 7.6±0.7 vs. 909.0±46.3 cells/field (P<0.0001); and mast cells 5.5±0.5 vs. 27.3±2.9 cells/field (P<0.0001)].

Figure 6.

Densities of (A) leucocytes, (B) B/T lymphocytes, (C) B lymphocytes, (D) T lymphocytes, (E) macrophages/monocytes and (F) mast cells in the lamina propria of the colon derived from normal control rats and rats with TNBS-induced colitis. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error. ***P<0.001 vs. controls. TNBS, trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid.

Correlation between endocrine and immune cells

The Spearman correlation coefficients and P-values for the correlations between different endocrine cell types and various immune cells are presented in Table II. The number of CgA, PYY, and PP-producing immune cells was observed to be negatively correlated with the number of specific types of immune cells, whilst positive correlations were observed for serotonin, oxyntomodulin, and somatostatin cells.

Table II.

Spearman's rank correlation coefficients (r) and P-values for the association between endocrine and immune cells in rats with TNBS-induced colitis.

| Immune cell type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endocrine cell type | Leukocytes | B/T lymphocytes | T lymphocytes | B lymphocytes | Macrophages/monocytes | Mast cells |

| Chromogranin A | r=−0.7 | r=−0.3 | r=−0.6 | r=−0.6 | r=−0.7 | r=−0.5 |

| P=0.04 | P=0.09 | P=0.009 | P=0.02 | P=0.008 | P=0.03 | |

| Serotonin | r=0.7 | r=0.7 | r=0.4 | r=0.6 | r=0.2 | r=0.4 |

| P=0.005 | P=0.009 | P=0.01 | P=0.02 | P=0.05 | P=0.1 | |

| Peptide YY | r=−0.5 | r=−0.7 | r=0.2 | r=−0.7 | r=−0.6 | r=0.7 |

| P=0.04 | P=0.002 | P=0.06 | P=0.002 | P=0.02 | P=0.7 | |

| Oxyntomdulin | r=0.2 | r=0.5 | r=0.6 | r=0.1 | r=0.1 | r=−0.6 |

| P=0.6 | P=0.02 | P=0.01 | P=0.7 | P=0.9 | P=0.02 | |

| Pancreatic polypeptide | r=−0.7 | r=−0.5 | r=−0.2 | r=−0.6 | r=−0.6 | r=−0.7 |

| P=0.004 | P=0.8 | P=0.5 | P=0.008 | P=0.01 | P=0.002 | |

| Somatostatin | r=0.6 | r=0.7 | r=0.1 | r=0.2 | r=−0.7 | r=−0.6 |

| P=0.02 | P=0.8 | P=0.7 | P=0.6 | P=0.0044 | P=0.02 | |

Discussion

TNBS-induced colitis in rats closely mimics human CD (34–39). Although this model exhibits clinical and morphological features similar to human CD (39–41), it lacks the chronicity observed in human CD (39). The present study observed that the frequency of all types of colonic endocrine cells was affected in rats with TNBS-induced colitis. In addition, abnormalities in the colonic endocrine cells were strongly correlated with the alterations in the number of different types of immune cells following the induction of colitis. These observations support the previously suggested role of gut hormones in immune activation and inflammation (21,22,42).

In the present study, the alterations in the number of colonic endocrine cells observed in rats with TNBS-induced colitis differ from those observed in rats with DSS-induced colitis in a previous study (31). In TNBS and DSS-induced colitis, the densities of serotonin and oxyntomodulin were increased, while the density of PP was reduced compared with normal controls. However, the CgA and PYY-producing immune cell densities were increased in DSS-induced colitis, whereas they were reduced in TNBS-induced colitis compared with normal controls. In addition, the density of somatostatin was reduced in DSS-induced colitis (31), however was increased in TNBS-induced colitis in the present study. Differences in the alterations of the number of colonic endocrine cells between CD and UC have been reported previously by El Salhy et al (1). This study demonstrated that the densities of CgA and serotonin were increased in CD and UC, while the densities of PYY and PP were reduced, and oxyntomodulin was decreased in CD only.

Although the abnormalities in the colonic endocrine cells in DSS-induced colitis were strongly correlated with leukocytes, B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, macrophages/monocytes and mast cells (31), the results for TNBS-induced colitis in the present study demonstrated that specific endocrine cell types were correlated with particular immune cell types. CgA is a member of the granin family (43,44), which is localized to gut endocrine cells (45–48), and is considered to be a common marker for gastrointestinal endocrine cells (49,50). The reduction in the density of CgA-producing cells observed in the present study may reflect reductions in the densities of all colonic endocrine cells following the induction of colitis by TNBS. The density of CgA-producing cells was negatively correlated with increases in all immune cell types except for B/T lymphocytes. CgA suppresses the release of interleukin (IL)-16 and IL-5, and consequently reduces the number of lymphocytes at sites of inflammation, and reduces the pro-inflammatory actions of lymphocytes and monocytes (51–53). In addition, CgA, inhibits the vascular leakage caused by tumor necrosis factor-α (54). CgA is generally considered to exert an anti-inflammatory effect (54). It can therefore be speculated that the reduced density of CgA results from a direct action exerted by immune cells.

In the present study, the observed increase in the density of colonic serotonin-producing cells in TNBS-induced colitis relative to controls is consistent with previous observations in patients with UC, CD and microscopic colitis, as well as animal models of colitis (1,3,55–57). The increased density of serotonin-producing cells in the present study was correlated with increases in the number of all types of immune cells examined, apart from macrophages/monocytes and mast cells. Lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells express serotonin receptors (58), and IL-13 receptors have been localized on serotonin cells (59). In addition, serotonin inhibits the apoptosis of immune cells, promotes the recruitment of T cells, affects the proliferation of lymphocytes and protects natural killer cells (60–63). Furthermore, a previous study demonstrated that there are fewer serotonin-producing cells in mice lacking T-lymphocyte receptors (51). Serotonin stimulates gastric and intestinal motility, and intestinal secretion (64,65). Therefore, the increase in serotonin may accelerate gastrointestinal motility and increase intestinal secretion thus resulting in diarrhea, which is the primary symptom in TNBS-induced colitis.

PYY is colocalized with oxyntomodulin in endocrine L cells (66,67). In the present study, the density of PYY reduced while oxyntomodulin increased, which indicates that L cells downregulate the expression of PYY, but upregulate the expression of oxyntomodulin in TNBS-induced colitis in rats. PYY stimulates the adhesion of macrophages, chemotaxis, phagocytosis and the production of superoxide anions (68). PYY mRNA has been detected in mouse macrophages (69). The precise interaction between oxyntomodulin and immune cells has not yet been determined. In the present study, the density of PYY cells was negatively correlated with increases in the number of B/T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes and macrophages/monocytes, whereas oxyntomodulin density was positively correlated with B/T lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, and mast cells. These results indicate the presence different interactions of PYY and oxyntomodulin with immune cells. PYY delays gastric emptying, is a pivotal mediator of the ileal brake, and stimulates the absorption of water and electrolytes (70). The reduction in the number of PYY-producing cells observed in the current study may have contributed to the acceleration of gastrointestinal motility and increased intestinal secretion observed in TNBS-induced colitis.

The reduction in the number of PP-producing cells observed in the current study is consistent with previous reports for UC and CD (1). However, the interaction between PP and immune cells remains to be fully elucidated. In the present study, PP density was negatively correlated with the number of B lymphocytes, macrophages/monocytes and mast cells. PP stimulates gastric acid secretion and the motility of the stomach and small intestine in addition to relaxing the gallbladder (64). The increased density of somatostatin cells in TNBS-induced colitis observed in the present study contradicts previous observations of UC, CD and DSS-induced colitis, where somatostatin cell density was reported to reduce (1,19,20). Somatostatin inhibits lymphocyte proliferation, immunoglobulin synthesis and the release of neutrophil elastase (71–75). In the present study, the density of somatostatin-producing cells was observed to be positively correlated with the number of macrophages/monocytes and mast cells. The strong correlation observed between alterations in PP and somatostatin-producing cell densities and specific immune cell types, indicate that they may be involved in the inflammatory process.

The present observations, demonstrating that alterations in the number of immune cells are strongly correlated with alterations in large intestinal cells in an animal model of human of Crohn's disease, support the debated suggestion of an interaction between intestinal hormones and the gut immune system. Understanding this interaction may improve our understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in IBD, and may provide us with novel therapeutic approaches to treat this condition.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by grants from the Helse-Vest regional health authority, (Bergen, Norway; grant no. 911978) and Helse-Fonna health organization (Haugesund, Norway; grant no. 40415).

References

- 1.El-Salhy M, Danielsson A, Stenling R, Grimelius L. Colonic endocrine cells in inflammatory bowel disease. J Intern Med. 1997;242:413–419. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Salhy M, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Chromogranin a cell density as a diagnostic marker for lymphocytic colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:3154–3159. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2249-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Salhy M, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. High densities of serotonin and peptide YY cells in the colon of patients with lymphocytic colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6070–6075. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Salhy M, Lomholt-Beck B, Gundersen TD. High chromogranin A cell density in the colon of patients with lymphocytic colitis. Mol Med Rep. 2011;4:603–605. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moran GW, Pennock J, McLaughlin JT. Enteroendocrine cells in terminal ileal Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:871–880. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moran GW, Leslie FC, McLaughlin JT. Crohn's disease affecting the small bowel is associated with reduced appetite and elevated levels of circulating gut peptides. Clin Nutr. 2013;32:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Besterman HS, Mallinson CN, Modigliani R, Christofides ND, Pera A, Ponti V, Sarson DL, Bloom SR. Gut hormones in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1983;18:845–852. doi: 10.3109/00365528309182104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Salhy M, Mazzawi T, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. The role of peptide YY in gastrointestinal diseases and disorders (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2013;31:275–282. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirotani Y, Mikajiri K, Ikeda K, Myotoku M, Kurokawa N. Changes of the peptide YY levels in the intestinal tissue of rats with experimental colitis following oral administration of mesalazine and prednisolone. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2008;128:1347–1353. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.128.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vona-Davis LC, McFadden DW. NPY family of hormones: Clinical relevance and potential use in gastrointestinal disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:1710–1720. doi: 10.2174/156802607782340966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Salhy M, Suhr O, Danielsson A. Peptide YY in gastrointestinal disorders. Peptides. 2002;23:397–402. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(01)00617-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tari A, Teshima H, Sumii K, Haruma K, Ohgoshi H, Yoshihara M, Kajiyama G, Miyachi Y. Peptide YY abnormalities in patients with ulcerative colitis. Jpn J Med. 1988;27:49–55. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine1962.27.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sciola V, Massironi S, Conte D, Caprioli F, Ferrero S, Ciafardini C, Peracchi M, Bardella MT, Piodi L. Plasma chromogranin a in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:867–871. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishop AE, Pietroletti R, Taat CW, Brummelkamp WH, Polak JM. Increased populations of endocrine cells in Crohn's ileitis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1987;410:391–396. doi: 10.1007/BF00712758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manocha M, Khan WI. Serotonin and GI disorders: An update on clinical and experimental studies. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2012;3:e13. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2012.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoyanova II, Gulubova MV. Mast cells and inflammatory mediators in chronic ulcerative colitis. Acta Histochem. 2002;104:185–192. doi: 10.1078/0065-1281-00641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto H, Morise K, Kusugami K, Furusawa A, Konagaya T, Nishio Y, Kaneko H, Uchida K, Nagai H, Mitsuma T, Nagura H. Abnormal neuropeptide concentration in rectal mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:525–532. doi: 10.1007/BF02355052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Payer J, Huorka M, Duris I, Mikulecky M, Kratochvílová H, Ondrejka P, Lukác L. Plasma somatostatin levels in ulcerative colitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1994;41:552–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe T, Kubota Y, Sawada T, Muto T. Distribution and quantification of somatostatin in inflammatory disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:488–494. doi: 10.1007/BF02049408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koch TR, Carney JA, Morris VA, Go VL. Somatostatin in the idiopathic inflammatory bowel diseases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:198–203. doi: 10.1007/BF02552546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan WI, Ghia JE. Gut hormones: Emerging role in immune activation and inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;161:19–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Margolis KG, Gershon MD. Neuropeptides and inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25:503–511. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328331b69e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bampton PA, Dinning PG. High resolution colonic manometry-what have we learnt?-A review of the literature 2012. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15:328. doi: 10.1007/s11894-013-0328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ameri P, Ferone D. Diffuse endocrine system, neuroendocrine tumors and immunity: What's new? Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:267–276. doi: 10.1159/000334612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farzi A, Reichmann F, Holzer P. The homeostatic role of neuropeptide Y in immune function and its impact on mood and behaviour. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2015;213:603–627. doi: 10.1111/apha.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Salhy M, Hausken T. The role of the neuropeptide Y (NPY) family in he pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Neuropeptides. 2016;55:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wheway J, Herzog H, Mackay F. NPY and receptors in immune and inflammatory diseases. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:1743–1752. doi: 10.2174/156802607782341046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wheway J, Herzog H, Mackay F. The Y1 receptor for NPY: A key modulator of the adaptive immune system. Peptides. 2007;28:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wheway J, Mackay CR, Newton RA, Sainsbury A, Boey D, Herzog H, Mackay F. A fundamental bimodal role for neuropeptide Y1 receptor in the immune system. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1527–1538. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Salhy M, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment options for lymphocytic colitis (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2013;32:263–270. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Salhy M, Hatlebakk JG, Gilja OH. The abnormalities in endocrine and immune cells are correlated in dextran-sulfate-sodium-induced colitis. Mol Med Rep. 2016 doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.6023. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Salhy M, Umezawa K, Gilja OH, Hatlebakk JG, Gundersen D, Hausken T. Amelioration of Severe TNBS Induced Colitis by Novel AP-1 and NF-κB Inhibitors in Rats. Sci World J. 2014;2014:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2014/813804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vermeulen W, De Man JG, Nullens S, Pelckmans PA, De Winter BY, Moreels TG. The use of colonoscopy to follow the inflammatory time course of TNBS colitis in rats. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011;74:304–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saleh M, Elson CO. Experimental inflammatory bowel disease: Insights into the host-microbiota dialog. Immunity. 2011;34:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SP. IBD Section, British Society of Gastroenterology: Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2004;53:V1–V16. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.043372. (Suppl 5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sands BE. New therapies for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86:1045–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez A, Billioud V, Peyrin-Biroulet C, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Adherence to anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases: A systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1528–1533. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31828132cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Danese S, Semeraro S, Armuzzi A, Papa A, Gasbarrini A. Biological therapies for inflammatory bowel disease: Research drives clinics. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2006;6:771–784. doi: 10.2174/138955706777698624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elson CO, Sartor RB, Tennyson GS, Riddell RH. Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1344–1367. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90599-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dieleman LA, Palmen MJ, Akol H, Bloemena E, Peña AS, Meuwissen SG, Van Rees EP. Chronic experimental colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) is characterized by Th1 and Th2 cytokines. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:385–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Low D, Nguyen DD, Mizoguchi E. Animal models of ulcerative colitis and their application in drug research. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;7:1341–1357. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S40107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Öhman L, Törnblom H, Simrén M. Crosstalk at the mucosal border: Importance of the gut microenvironment in IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:36–49. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buffa R, Mare P, Gini A, Salvadore M. Chromogranins A and B and secretogranin II in hormonally identified endocrine cells of the gut and the pancreas. Basic Appl Histochem. 1988;32:471–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eiden LE. Is chromogranin a prohormone? Nature. 1987;325:301. doi: 10.1038/325301a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buffa R, Capella C, Fontana P, Usellini L, Solcia E. Types of endocrine cells in the human colon and rectum. Cell Tissue Res. 1978;192:227–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00220741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curry WJ, Johnston CF, Hutton JC, Arden SD, Rutherford NG, Shaw C, Buchanan KD. The tissue distribution of rat chromogranin A-derived peptides: Evidence for differential tissue processing from sequence specific antisera. Histochemistry. 1991;96:531–538. doi: 10.1007/BF00267079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Portela-Gomes GM, Stridsberg M. Selective processing of chromogranin A in the different islet cells in human pancreas. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:483–490. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Portela-Gomes GM, Stridsberg M. Chromogranin A in the human gastrointestinal tract: An immunocytochemical study with region-specific antibodies. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50:1487–1492. doi: 10.1177/002215540205001108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taupenot L, Harper KL, O'Connor DT. The chromogranin-secretogranin family. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1134–1149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wiedenmann B, Huttner WB. Synaptophysin and chromogranins/secretogranins-widespread constituents of distinct types of neuroendocrine vesicles and new tools in tumor diagnosis. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1989;58:95–121. doi: 10.1007/BF02890062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spiller R. Serotonin and GI clinical disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1072–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Egger M, Beer AG, Theurl M, Schgoer W, Hotter B, Tatarczyk T, Vasiljevic D, Frauscher S, Marksteiner J, Patsch JR, et al. Monocyte migration: A novel effect and signaling pathways of catestatin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;598:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feistritzer C, Mosheimer BA, Colleselli D, Wiedermann CJ, Kähler CM. Effects of the neuropeptide secretoneurin on natural killer cell migration and cytokine release. Regul Pept. 2005;126:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferrero E, Magni E, Curnis F, Villa A, Ferrero ME, Corti A. Regulation of endothelial cell shape and barrier function by chromogranin A. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;971:355–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bertrand PP, Bertrand RL. Serotonin release and uptake in the gastrointestinal tract. Auton Neurosci. 2010;153:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qian BF, El-Salhy M, Melgar S, Hammarström ML, Danielsson A. Neuroendocrine changes in colon of mice with a disrupted IL-2 gene. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;120:424–433. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oshima S, Fujimura M, Fukimiya M. Changes in number of serotonin-containing cells and serotonin levels in the intestinal mucosa of rats with colitis induced by dextran sodium sulfate. Histochem Cell Biol. 1999;112:257–263. doi: 10.1007/s004180050445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cloëz-Tayarani I, Changeux JP. Nicotine and serotonin in immune regulation and inflammatory processes: A perspective. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:599–606. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0906544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang H, Steeds J, Motomura Y, Deng Y, Verma-Gandhu M, El-Sharkawy RT, McLaughlin JT, Grencis RK, Khan W. CD4+ T cell-mediated immunological control of enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia and 5-hydroxytryptamine production in enteric infection. Gut. 2007;56:949–957. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.103226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stefulj J, Cicin-Sain L, Schauenstein K, Jernej B. Serotonin and immune response: Effect of the amine on in vitro proliferation of rat lymphocytes. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2001;9:103–108. doi: 10.1159/000049013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Betten A, Dahlgren C, Hermodsson S, Hellstrand K. Serotonin protects NK cells against oxidatively induced functional inhibition and apoptosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laberge S, Cruikshank WW, Beer DJ, Center DM. Secretion of IL-16 (lymphocyte chemoattractant factor) from serotonin-stimulated CD8+ T cells in vitro. J Immunol. 1996;156:310–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soga F, Katoh N, Inoue T, Kishimoto S. Serotonin activates human monocytes and prevents apoptosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1947–1955. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.El-Salhy M, Seim I, Chopin L, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Irritable bowel syndrome: The role of gut neuroendocrine peptides. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:2783–2800. doi: 10.2741/e583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.El-Salhy M. Irritable bowel syndrome: Diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment options. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5151–5163. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i37.5151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spångéus A, Forsgren S, el-Salhy M. Does diabetic state affect co-localization of peptide YY and enteroglucagon in colonic endocrine cells? Histol Histopathol. 2000;15:37–41. doi: 10.14670/HH-15.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pyarokhil AH, Ishihara M, Sasaki M, Kitamura N. The developmental plasticity of colocalization pattern of peptide YY and glucagon-like peptide-1 in the endocrine cells of bovine rectum. Biomed Res. 2012;33:35–38. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.33.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De la Fuente M, Bernaez I, Del Rio M, Hernanz A. Stimulation of murine peritoneal macrophage functions by neuropeptide Y and peptide YY. Involvement of protein kinase C. Immunology. 1993;80:259–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Macia L, Yulyaningsih E, Pangon L, Nguyen AD, Lin S, Shi YC, Zhang L, Bijker M, Grey S, Mackay F, et al. Neuropeptide Y1 receptor in immune cells regulates inflammation and insulin resistance associated with diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2012;61:3228–3238. doi: 10.2337/db12-0156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.El-Salhy M, Gundersen D, Gilja OH, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Is irritable bowel syndrome an organic disorder? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:384–400. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i2.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Payan DG, Hess CA, Goetzl EJ. Inhibition by somatostatin of the proliferation of T-lymphocytes and Molt-4 lymphoblasts. Cell Immunol. 1984;84:433–438. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Adeyemi EO, Savage AP, Bloom SR, Hodgson HJ. Somatostatin inhibits neutrophil elastase release in vitro. Peptides. 1990;11:869–871. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(90)90206-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stanisz AM, Befus D, Bienenstock J. Differential effects of vasoactive intestinal peptide, substance P, and somatostatin on immunoglobulin synthesis and proliferations by lymphocytes from Peyer's patches, mesenteric lymph nodes, and spleen. J Immunol. 1986;136:152–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scicchitano R, Dazin P, Bienenstock J, Payan DG, Stanisz AM. Distribution of somatostatin receptors on murine spleen and Peyer's patch T and B lymphocytes. Brain Behav Immun. 1987;1:173–184. doi: 10.1016/0889-1591(87)90019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scicchitano R, Stanisz AM, Payan DG, Kiyono H, McGhee JR, Bienenstock J. Expression of substance P and somatostatin receptors on a T helper cell line. Adv Exp Med Biol 216A. 1987:185–190. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5344-7_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]