Abstract

The present study aimed to evaluate the effects of Enterococcus faecalis, inactivated by the common intracanal irrigants sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) and chlorhexidine (CHX), on osteoblasts. E. faecalis was inactivated with 2% CHX or 5.25% NaOCl. Subsequently, the Cell Counting kit-8 assay was used to examine the effects of CHX- and NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis on MC3T3-E1 osteoblast cell proliferation. Alizarin red staining was used to determine osteoblast mineralization, and osteogenic induction was quantified by determining the optical density of the dye solution. The relative expression levels of osteogenic genes were detected after 1, 4, 7 and 14 days of stimulation with CHX- and NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. The results indicated that CHX-inactivated E. faecalis inhibited osteoblast proliferation, whereas NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis did not suppress cell proliferation. Various concentrations of CHX- and NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis induced different degrees of osteoblast mineralization. The expression levels of osteocalcin, alkaline phosphatase, runt-related transcription factor 2, osteopontin and osterix were upregulated in cells following stimulation with 107 and 105 colony-forming units/ml E. faecalis inactivated by CHX and NaOCl; the upregulation of these osteogenic genes occurred at various time points. In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that CHX-inactivated E. faecalis exerted more of an effect on osteoblast proliferation compared with NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis. In addition, CHX- and NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis was able to induce mineralization and relevant osteogenic gene expression in osteoblast cells.

Keywords: Enterococcus faecalis, sodium hypochlorite, chlorhexidine, osteoblast

Introduction

The presence of pathogenic bacteria in the root canal is the major cause of pulpal and periapical pathology (1–3). Pathogens generate toxins, and induce progressive and invasive damage to the periradicular tissue. Enterococcus faecalis, which is a common drug-resistant pathogen, is able to survive extreme conditions, including starvation and an alkaline environment, and possesses several virulence factors that cause persistent pulpal and periapical infections (4,5). E. faecalis, and other common pathogens, are able to activate the immune response and destroy periapical tissue (6).

The balance between osteoblasts and osteoclasts is responsible for bone resorption and formation (7). Osteoblasts are well known for their role in bone formation, and are essential in the regeneration and reconstruction of periapical tissue. Osteoblasts have several key functions, including bone matrix synthesis, osteoblast regulation of osteoclastogenesis, endocrine functions and hematopoietic stem cell regulation (8). In addition, osteoblasts are associated with various important regulatory pathways, such as Wnt signaling and runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) (9,10).

Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) and chlorhexidine (CHX) are common intracanal medicaments, which exert bactericidal effects on pathogens in the root canal (11,12). The purpose of root canal therapy is to effectively eradicate pathogenic bacteria using mechanical instruments and antibacterial agents. However, little information is currently available regarding the effects of inactivated pathogens on periapical cells. Since E. faecalis is frequently isolated in persistent periapical infection, and due to the important role of osteoblasts in periapical lesion recovery, the present study aimed to examine the effects of inactivated E. faecalis on the proliferation and induction of osteogenic differentiation in the pre-osteoblast cell line MC3T3-E1. Furthermore, the relative expression levels of osteogenic genes were detected following exposure to various concentrations of inactivated E. faecalis.

Materials and methods

Bacteria and cell culture

E. faecalis [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)® 29212™; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA] was streaked on brain heart infusion agar (BHI; Difco; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and was cultured aerobically at 37°C for 24 h. A single bacterial colony was inoculated into 5 ml BHI medium and grown to the exponential phase [bacterial concentration, ~109 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml]. The MC3T3-E1 osteoblast cell line (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) was used in the present study. Osteoblasts were cultured in minimum essential medium, alpha modified (α-MEM; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Inactivation of E. faecalis

The E. faecalis culture (concentration, 109 CFU/ml) was centrifuged at 6,343 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was discarded. The E. faecalis deposit was then resuspended in 5.25% NaOCl (Shanghai ChemDo International Trade Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) or 2% CHX (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) for 5 min. The NaOCl challenge was discontinued by 0.6% sodium thiosulfate, and the CHX challenge was discontinued by 5% polysorbate 80 and 0.07% soybean lecithin. To verify the complete inactivation of bacteria, 100 µl inactivated E. faecalis was spread onto BHI agar and cultured at 37°C for 48 h; no cell growth indicated complete inactivation. Furthermore, to remove the remnants of NaOCl or CHX and the neutralizers, the inactivated E. faecalis cultures were centrifuged 6,343 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were discarded. Bacterial deposits were resuspended in PBS after being washed twice in sterile PBS.

Cell proliferation assay

CHX- or NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis was gradually diluted ten-fold with α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Osteoblasts were seeded in 96-well tissue culture plates at 2×104 cells/well, and were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 24 h. Once the cells were attached to the bottom of the plates, the supernatant was removed and various concentrations of inactivated E. faecalis (10–104 fold dilution) were added to the wells, in order to evaluate the effects of inactivated E. faecalis on cell proliferation. Cells without the addition of E. faecalis were used as the control group. The medium was replaced every 2 days. Cell proliferation was assessed using the Cell Counting kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) on days 1, 2, 4, 7 and 14 according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Induction of osteogenic differentiation

For osteogenic induction, osteoblasts were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1×105 cells/well, and were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After cells grew to 50% confluence, CHX- or NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis was diluted to 107, 106 and 105 CFU/ml using α-MEM medium (supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin), and was added to the wells. Osteogenic medium (10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.2 mM ascorbic acid and 0.1 µM dexamethasone in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin) was used as a positive control, and α-MEM medium was used as a negative control. The 6-well plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, and the medium was replaced every 2 days. After 7 days, cells that were adherent to the bottom of the wells were stained with 0.5% Alizarin Red S solution (pH 4.2; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore), and images were captured using a stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Red staining indicated the presence of calcium deposits. For quantitative analysis, cells that were adherent to the bottom of the 6-wells for 7 days were washed twice with sterile PBS. The bound dye was then eluted with 1.5 ml 0.5 M hydrochloric acid-alcohol solution (37% hydrochloric acid to dehydrated alcohol ratio, 1:24). Osteogenic induction was quantified by determining the optical density of the solution at 405 nm. Three independent experiments were conducted, each of which was performed in triplicate.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

The relative expression levels of osteogenic genes under various conditions were analyzed by RT-qPCR. Induction of osteogenic differentiation by inactivated E. faecalis was detected as aforementioned. Total RNAs were isolated from osteoblasts stimulated with 107 and 105 CFU/ml 2% CHX- or 5.25% NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis for 2, 4, 7 and 14 days using TRIzol Max Bacterial RNA Isolation kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). For cDNA synthesis, 2 µg RNA was used as a template and was reverse transcribed using the PrimeScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. An additional reaction containing no reverse transcriptase was used to confirm the absence of genomic DNA. The primer sequences for the following osteogenic genes: Osteocalcin (OCN), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), Runx2, osteopontin (OPN) and osterix (OSX), are presented in Table I. Total cDNA abundance between the test samples was normalized using GAPDH as a control. qPCR was conducted using a RealMasterMix SYBR Green PCR kit [cat. no. FP202; Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China] in a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and was replicated four times in a 20 µl reaction mixture containing 8 µl 2.5X RealMasterMix, 1 µl 20X SYBR solution, 0.5 µl primers (10 µM) and 5 ng cDNA. The reaction conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 95°C for 60 sec followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 40 sec. Relative gene expressions were calculated using the Cq method (13).

Table I.

Primers used to evaluate the expression of osteogenic genes in MC3T3-E1 cells.

| Gene | Primer sequences (5′-3′) | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| OCN | F: TGACCTCACAGATGCCAAGC; R: GCGCCGGAGTCTGTTCACTA | 94 |

| ALP | F: CCAGTGAGCAGGACACGATG; R: TGAAGGGAGCCAGTCCAAAG | 108 |

| Runx2 | F: GAACTACTCCGCCGAGCTCC; R: TGAAACTCTTGCCTCGTCCG | 107 |

| OPN | F: TGGCAGTGATTTGCTTTTGC; R: GGGTGCAGGCTGTAAAGCTTC | 100 |

| OSX | F: TCGTCTGACTGCCTGCCTAGT; R: TTGCCTGGACCTGGTGAGAT | 107 |

| GAPDH | F: CGTGTTCCTACCCCCAATGT; R: TGTCATCATACTTGGCAGGTTTCT | 73 |

F, forward; R, reverse; OCN, ostoecalcin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; Runx2, runt-related transcription factor 2; OPN, osteopontin; OSX, osterix.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform statistical analyses. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey honestly significant difference test were used to compare the proliferation of osteoblasts stimulated with E. faecalis inactivated by the two drugs. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. The same statistical tests were used to compare the degree of mineralization and the relative expression levels of osteogenic genes in osteoblasts stimulated with the various types of inactivated E. faecalis. All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Effects of inactivated E. faecalis on osteoblast growth

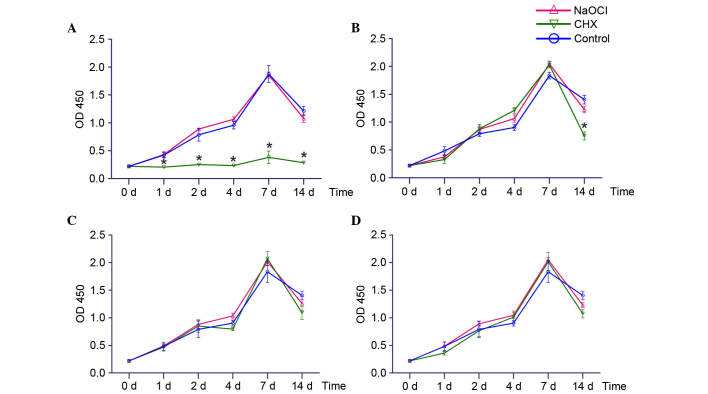

The CCK-8 assay was used to evaluate the effects of inactivated E. faecalis on osteoblast proliferation (Fig. 1). At a concentration of 108 CFU/ml, CHX-inactivated E. faecalis significantly inhibited osteoblast growth at various time points; however, NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis did not suppress osteoblast proliferation, and the osteoblast proliferation curve was similar to the control group (Fig. 1A). At a concentration of 107 CFU/ml, osteoblasts exhibited similar growth curves in the CHX-inactivated, NaOCl -inactivated and control groups between 0 and 7 days; however, osteoblast proliferation was significantly reduced in the CHX-inactivated group compared with in the NaOCl-inactivated group at day 14 (Fig. 1B). When inactivated E. faecalis was diluted to 106 or 105 CFU/ml, osteoblast proliferation was similar in the CHX-inactivated, NaOCl-inactivated and control groups (Fig. 1C and D).

Figure 1.

Effects of the various concentrations of Enterococcus faecalis inactivated by 2% CHX or 5.25% NaOCl on the proliferation of osteoblasts. (A) 108 CFU/ml E. faecalis; (B) 107 CFU/ml E. faecalis; (C) 106 CFU/ml E. faecalis; (D) 105 CFU/ml E. faecalis. Y-axes represent osteoblast proliferation, as detected by measuring the OD at 450 nm; X-axes represent duration of stimulation. *P<0.05 CHX-inactivated group vs. control group at the same time point. CHX, chlorhexidine; NaOCl, sodium hypochlorite; CFU, colony-forming units; OD, optical density.

Effects of inactivated E. faecalis on osteogenic induction of osteoblasts

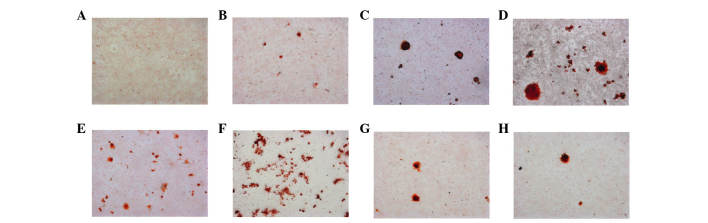

Alizarin red S staining was used to detect mineralized nodules of osteoblasts stimulated by inactivated E. faecalis (Fig. 2). Stimulation of osteoblasts with 107 CFU/ml 2% CHX-inactivated E. faecalis markedly induced the formation of several mineralized nodules (Fig. 2F). The number of mineralized nodules was reduced following stimulation with 106 or 105 CFU/ml E. faecalis; however, the size of the mineralized nodules was markedly increased (Fig. 2G and H). Stimulation of osteoblasts with 107 CFU/ml 5.25% NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis induced a slight increase in mineralized nodules (Fig. 2B), and the size of the mineralized nodules was markedly increased following stimulation with 106 CFU/ml E. faecalis, as compared with 107 CFU/ml E. faecalis. Stimulation with 105 CFU/ml E. faecalis resulted in induction of the largest mineralized nodules (Fig. 2C and D).

Figure 2.

Alizarin red S staining of mineralized nodules in osteoblasts stimulated with various concentrations of inactivated E. faecalis. (A) Negative control; (B) 107 CFU/ml, (C) 106 CFU/ml and (D) 105 CFU/ml 5.25% NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis; (E) positive control; (F) 107 CFU/ml, (G) 106 CFU/ml and (H) 105 CFU/ml 2% CHX-inactivated E. faecalis. Magnification, ×100. CHX, chlorhexidine; NaOCl, sodium hypochlorite; CFU, colony-forming units.

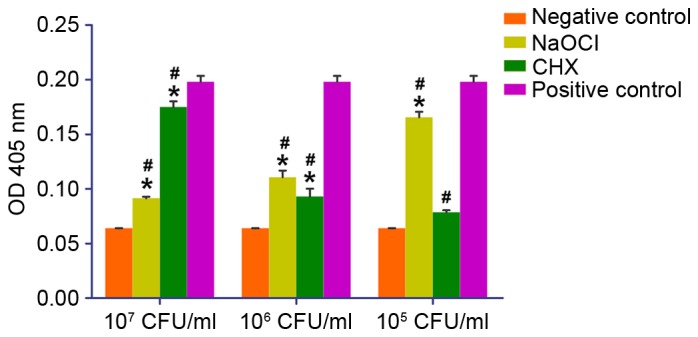

Quantification of the degree of osteoblast mineralization demonstrated that there was a statistical difference between cells stimulated with 107 CFU/ml 2% CHX- or 5.25%-inactivated NaOCl E. faecalis (P<0.05); and mineralization was higher in both groups compared with the negative control group. Following stimulation with 106 CFU/ml inactivated E. faecalis, no statistically significant difference was detected between the NaOCl-inactivated and CHX-inactivated E. faecalis groups; however, mineralization was higher in both groups compared with the negative control group, and was lower compared with the positive control group (P<0.05). At a concentration of 105 CFU/ml, stimulation with NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis resulted in a significantly higher degree of mineralization compared with in the CHX-inactivated E. faecalis group, and mineralization was lower in both groups compared with in the positive control group (P<0.05; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Quantitative analysis of the degree of mineralization in osteoblasts treated with various concentrations of NaOCl- and CHX-inactivated Enterococcus faecalis. *P<0.05 vs. negative control group; #P<0.05 vs. positive control group. CHX, chlorhexidine; NaOCl, sodium hypochlorite; CFU, colony-forming units; OD, optical density.

Expression of osteogenic genes in response to inactivated E. faecalis

Osteoblasts were stimulated with 107 CFU/ml CHX-inactivated E. faecalis (107 CHX-Ef), 105 CFU/ml CHX-inactivated E. faecalis (105 CHX-Ef), 107 CFU/ml NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis (107 NaOCl-Ef) or 105 CFU/ml NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis (105 NaOCl-Ef). The expression levels of osteogenic genes were then detected by RT-qPCR. OCN is an important marker of osteogenesis. Following stimulation with 107 CHX-Ef for 2 or 4 days the expression levels of OCN were significantly upregulated compared with the negative control group, and were lower compared with the positive control group (P<0.05). In addition, stimulation with 107 CHX-Ef, 105 CHX-Ef or 107 NaOCl-Ef for 7 or 14 days induced the transcription of OCN; the expression levels of OCN in these groups were significantly increased compared with in the 105 NaOCl-Ef group (P<0.05; Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Expression levels of OCN in response to various concentrations of inactivated Enterococcus faecalis for (A) 2, (B) 4, (C) 7 and (D) 14 days. *P<0.05 vs. negative control group; #P<0.05 vs. positive control group. CHX, chlorhexidine; NaOCl, sodium hypochlorite; CFU, colony-forming units; OCN, osteocalcin.

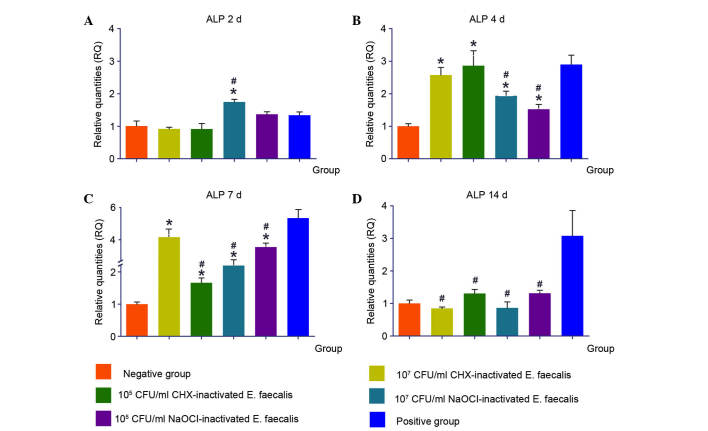

Following 2 days stimulation with 107 NaOCl-Ef the expression levels of ALP were significantly increased

After 4 and 7 days stimulation with 107 CHX-Ef, 105 CHX-Ef, 107 NaOCl-Ef and 105 NaOCl-Ef the expression levels of ALP were upregulated. However, after 14 days, the various concentrations of inactivated E. faecalis did not induce upregulation of ALP, and the expression levels were similar to those in the negative control group (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Expression levels of ALP in response to various concentrations of inactivated Enterococcus faecalis for (A) 2, (B) 4, (C) 7 and (D) 14 days. *P<0.05 vs. negative control group; #P<0.05 vs. positive control group. CHX, chlorhexidine; NaOCl, sodium hypochlorite; CFU, colony-forming units; ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

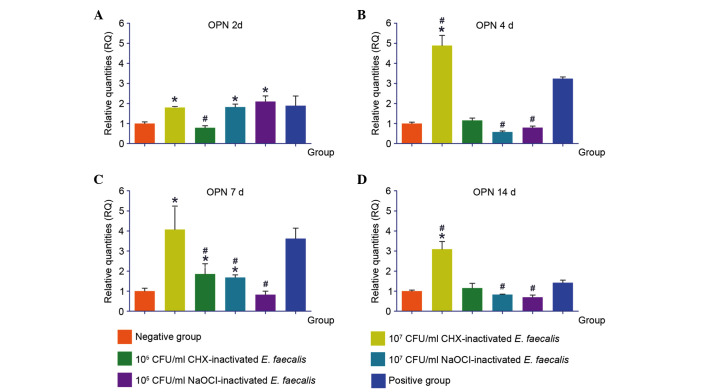

Following 2 days of stimulation with 107 CHX-Ef, 107 NaOCl-Ef and 105 NaOCl-Ef, the expression levels of OPN were upregulated. Stimulation with 107 CHX-Ef for 4, 7 or 14 days induced the transcription of OPN to the highest levels, which were higher than in the positive control group. The expression levels of OPN were not significantly different between the 105 CHX-Ef, 107 NaOCl-Ef and 105 NaOCl-Ef groups after 4 or 14 days stimulation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Expression levels of OPN in response to various concentrations of inactivated Enterococcus faecalis for (A) 2, (B) 4, (C) 7 and (D) 14 days. *P<0.05 vs. negative control group; #P<0.05 vs. positive control group. CHX, chlorhexidine; NaOCl, sodium hypochlorite; CFU, colony-forming units; OPN, osteopontin.

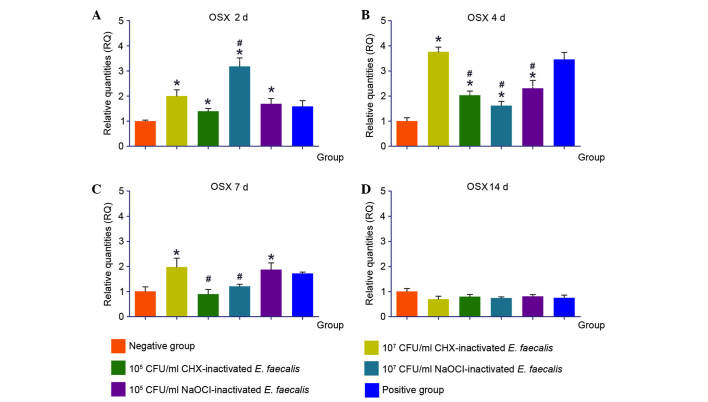

OSX is a vital regulatory factor for osteoblast differentiation and bone development. The expression levels of OSX were upregulated in response to stimulation with 107 CHX-Ef, and the highest level was reached after 4 days. Similarly, following stimulation with 105 CHX-Ef, transcription of OSX was induced to its highest level after 4 days, and was decreased to normal levels after 7 and 14 days. After 2 and 4 days of stimulation, 107 NaOCl-Ef and 105 NaOCl-Ef upregulated OSX expression. Furthermore, following 14 days of stimulation, the expression levels of OSX in the experimental groups were reduced to negative control levels (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Expression levels of OSX in response to various concentrations of inactivated Enterococcus faecalis for (A) 2, (B) 4, (C) 7 and (D) 14 days. *P<0.05 vs. negative control group; #P<0.05 vs. positive control group. CHX, chlorhexidine; NaOCl, sodium hypochlorite; CFU, colony-forming units; OSX, osterix.

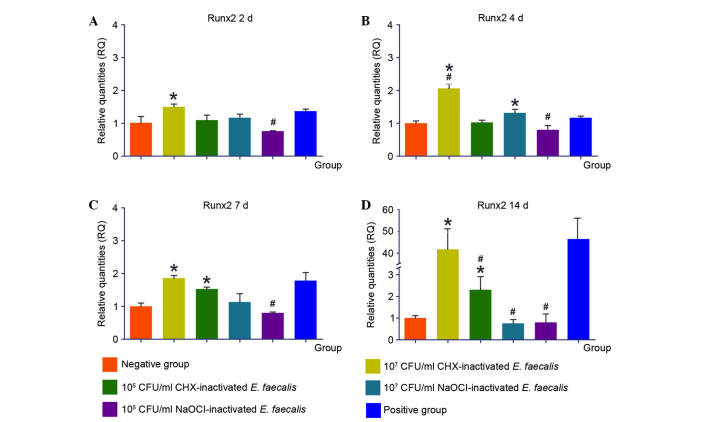

Runx2 is an important transcription factor associated with bone formation. Transcription of Runx2 was upregulated in response to stimulation with 107 CHX-Ef, and a maximum was reached after 14 days. Following stimulation with 105 CHX-Ef, the upregulation of Runx2 was observed after 7 and 14 days. NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis did not induce the upregulation of Runx2 compared with CHX-inactivated E. faecalis during the 14 days of stimulation (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Expression levels of Runx2 in response to various concentrations of inactivated Enterococcus faecalis for (A) 2, (B) 4, (C) 7 and (D) 14 days. *P<0.05 vs. negative control group; #P<0.05 vs. positive control group. CHX, chlorhexidine; NaOCl, sodium hypochlorite; CFU, colony-forming units; Runx2, runt-related transcription factor 2.

Discussion

E. faecalis is one of the most commonly implicated pathogens in persistent and secondary root canal infection (14,15). The objective of antibacterial intracanal medicament application is to inactivate pathogens, such as E. faecalis, in the root canal. It is well known that living pathogens exert pathogenicity and destroy periapical tissue; however, when living pathogens in periapical tissue are killed by intracanal medicaments and are not completely cleared, it remains unknown as to the effects of the dead bacteria on periapical bone tissue healing. The present study demonstrated that high concentrations of E. faecalis inactivated by CHX significantly inhibited osteoblast proliferation, whereas NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis did not affect osteoblast growth. E. faecalis has several virulence factors, including lytic enzymes, cytolysin, aggregation substance, pheromones and lipoteichoic acid (16). CHX at a concentration of 2% possesses bactericidal activity and induces precipitation of cytoplasmic contents (17). The cytoplasmic contents of E. faecalis contain numerous virulence factors, and exert pathogenicity. Therefore, osteoblast growth was suppressed by the efflux of pathogenic cytoplasmic components in CHX-inactivated E. faecalis. NaOCl exerts its bactericidal mechanism via chlorine. NaOCl releases chlorine, which forms chloramines that interfere with cell metabolism when exposed to organic tissue. Chlorine generates irreversible oxidation of sulfhydryl groups of essential bacterial enzymes, thus inhibiting bacterial enzyme action and resulting in degradation of E. faecalis virulence factors (18). Therefore, osteoblast proliferation was not affected by NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis due to the degradation of virulence factors.

The presence of mineralized nodules is a marker of osteogenic differentiation. Analysis of the degree of osteoblastic mineralization demonstrated that low concentrations of NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis and high concentrations of CHX-inactivated E. faecalis induced increased levels of mineralization. High concentrations of CHX can destroy large amounts of E. faecalis, thus leading to the increased efflux of cytoplasmic compounds, which may stimulate the generation of mineralized nodules. This is a self-defense mechanism of osteoblasts, and mineralized nodules defend osteoblasts against virulence factors (19). However, it remains unclear as to how low concentrations of NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis increased the number of mineralized nodules. It may be hypothesized that NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis generates a certain substance that inhibits mineralized nodule formation, and when the substance is at low concentrations it may not be enough to hinder osteogenesis of osteoblasts. This hypothesis requires further study.

OCN is a marker of bone formation, which has a regulatory role in mineralization (20,21). CHX-inactivated E. faecalis significantly upregulated the expression levels of OCN after 7 and 14 days, thus indicating that the virulence factors released by E. faecalis may induce osteogenesis of osteoblasts. Furthermore, 107 CFU/ml NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis also induced OCN expression, which indicated that the substances released by NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis may still induce the formation of OCN, but only at high concentrations. The expression levels of Runx2 exhibited similar alterations to OCN gene expression following stimulation with CHX or NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis. Runx2 acts upstream of OCN, and regulates OCN gene transcription. Runx2 serves a key role in osteoblast differentiation (9). OPN has an important role in biomineralization, and inhibits the formation and growth of hydroxyapatite and other biominerals (22). The expression levels of OPN were not significantly upregulated following stimulation with inactivated E. faecalis, which were conducive to biomineralization of osteoblasts. However, 107 CFU/ml CHX-inactivated E. faecalis was still able to induce transcription of OPN. The high concentrations of bacterial virulence factors may induce production of OPN and activate bone resorption. ALP activity is considered a biochemical marker for osteoblastic activity (23). The present study demonstrated that ALP expression was upregulated after 4 and 7 days stimulation, thus indicating that the osteoblastic activity of osteoblasts reached the active phase after 4 or 7 days stimulation with CHX- and NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis.

OSX is a key transcription factor for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation, which acts downstream of Runx2 to regulate the expression of several osteogenic factors (24,25). OSX is a marker of the earlier stages of osteoblast differentiation. The present study indicated that upregulation of OSX occurred following 2 and 4 days of exposure to inactivated E. faecalis, whereas after 14 days, the expression levels of OSX were not significantly altered. Similar changes in expression were detected in the positive control group; osteogenic medium did not induce OSX expression at the late stage. This result indicated that OSX serves a role in the earlier stages of osteoblast differentiation.

Metabolites and virulence factors are released after bacteria are killed by antimicrobial agents. NaOCl exerts non-specific proteolytic effects, and the substances released by E. faecalis may be partly degraded (12). The substances released by the inactivated E. faecalis are very complex and may be partially degraded by non-specific proteolytic effects of NaOCl (12). Certain substances may not be degraded and remain. Therefore, the complex compositions may induce the different expression of osteogenic genes. CHX does not exert proteolytic effects, and the pathogenic factors are predominantly from the substances released by E. faecalis, and thereby exhibited concentration-dependent regulation of osteogenic gene transcription.

In conclusion, CHX-inactivated E. faecalis may inhibit osteoblast proliferation, whereas NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis did not affect osteoblast growth. CHX- and NaOCl-inactivated E. faecalis were associated with different levels of osteogenic differentiation of osteoblasts, and activated the expression of osteogenic genes. Additional studies are required to establish a standard protocol for the use of intracanal medications in the clinic. The results of the current study suggested that NaOCl irrigant may be superior to CHX irrigant regarding its effects on the osteogenic differentiation of osteoblasts.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Guangzhou Science Technology Project (201607010271) and the Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (2014A030313026).

References

- 1.Narayanan LL, Vaishnavi C. Endodontic microbiology. J Conserv Dent. 2010;13:233–239. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.73386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peciuliene V, Maneliene R, Balcikonyte E, Drukteinis S, Rutkunas V. Microorganisms in root canal infections: A review. Stomatologija. 2008;10:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rôças IN, Siqueira JF., Jr Root canal microbiota of teeth with chronic apical periodontitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:3599–3606. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00431-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Portenier I, Waltimo TMT, Haapasalo M. Enteroccus faecalis - the root canal survivor and ‘star’ in posttreatment disease. Endod Top. 2003;6:135–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-1546.2003.00040.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuart CH, Schwartz SA, Beeson TJ, Owatz CB. Enterococcus faecalis: Its role in root canal treatment failure and current concepts in retreatment. J Endod. 2006;32:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siqueira JF, Jr, Rôças IN. Bacterial pathogenesis and mediators in apical periodontitis. Braz Dent J. 2007;18:267–280. doi: 10.1590/S0103-64402007000400001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao X. Targeting osteoclast-osteoblast communication. Nat Med. 2011;17:1344–1346. doi: 10.1038/nm.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capulli M, Paone R, Rucci N. Osteoblast and osteocyte: Games without frontiers. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2014;561:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruderer M, Richards RG, Alini M, Stoddart MJ. Role and regulation of RUNX2 in osteogenesis. Eur Cell Mater. 2014;28:269–286. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v028a19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang R, Oyajobi BO, Harris SE, Chen D, Tsao C, Deng HW, Zhao M. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling activates bone morphogenetic protein 2 expression in osteoblasts. Bone. 2013;52:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanisavaran ZM. Chlorhexidine gluconate in endodontics: An update review. Int Dent J. 2008;58:247–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2008.tb00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohammadi Z. Sodium hypochlorite in endodontics: An update review. Int Dent J. 2008;58:329–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2008.tb00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naghmouchi K, Le Lay C, Baah J, Drider D. Antibiotic and antimicrobial peptide combinations: Synergistic inhibition of Pseudomonas fluorescens and antibiotic-resistant variants. Res Microbiol. 2012;163:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins B, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. The impact of nisin on sensitive and resistant mutants of Listeria monocytogenes in cottage cheese. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;110:1509–1514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piper C, Draper LA, Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. A comparison of the activities of lacticin 3147 and nisin against drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus species. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:546–551. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghiselli R, Giacometti A, Cirioni O, Dell'Acqua G, Mocchegiani F, Orlando F, D'Amato G, Rocchi M, Scalise G, Saba V. RNAIII-inhibiting peptide and/or nisin inhibit experimental vascular graft infection with methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;27:603–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartke A, Giard JC, Laplace JM, Auffray Y. Survival of Enterococcus faecalis in an oligotrophic microcosm: Changes in morphology, development of general stress resistance, and analysis of protein synthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4238–4245. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4238-4245.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katono T, Kawato T, Tanabe N, Suzuki N, Iida T, Morozumi A, Ochiai K, Maeno M. Sodium butyrate stimulates mineralized nodule formation and osteoprotegerin expression by human osteoblasts. Arch Oral Biol. 2008;53:903–909. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lombardi G, Perego S, Luzi L, Banfi G. A four-season molecule: Osteocalcin. Updates in its physiological roles. Endocrine. 2015;48:394–404. doi: 10.1007/s12020-014-0401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brennan-Speranza TC, Conigrave AD. Osteocalcin: An osteoblast-derived polypeptide hormone that modulates whole body energy metabolism. Calcif Tissue Int. 2015;96:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00223-014-9931-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gericke A, Qin C, Spevak L, Fujimoto Y, Butler WT, Sørensen ES, Boskey AL. Importance of phosphorylation for osteopontin regulation of biomineralization. Calcif Tissue Int. 2005;77:45–54. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-1288-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farley JR, Hall SL, Tanner MA, Wergedal JE. Specific activity of skeletal alkaline phosphatase in human osteoblast-line cells regulated by phosphate, phosphate esters, and phosphate analogs and release of alkaline phosphatase activity inversely regulated by calcium. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:497–508. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SH, Jeong HM, Han Y, Cheong H, Kang BY, Lee KY. Prolyl isomerase Pin1 regulates the osteogenic activity of Osterix. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;400:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang C. Transcriptional regulation of bone formation by the osteoblast-specific transcription factor Osx. J Orthop Surg Res. 2010;5:37. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-5-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]