Abstract

AIM

To determine the sensitivity and specificity of liver stiffness measurement (LSM) and serum markers (SM) for liver fibrosis evaluation in chronic hepatitis C.

METHODS

Between 2012 and 2014, 81 consecutive hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients had METAVIR score from liver biopsy compared with concurrent results from LSM [transient elastography (TE) [FibroScan®/ARFI technology (Virtual Touch®)] and SM [FIB-4/aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI)]. The diagnostic performance of these tests was assessed using receiver operating characteristic curves. The optimal cut-off levels of each test were chosen to define fibrosis stages F ≥ 2, F ≥ 3 and F = 4. The Kappa index set the concordance analysis.

RESULTS

Fifty point six percent were female and the median age was 51 years (30-78). Fifty-six patients (70%) were treatment-naïve. The optimal cut-off values for predicting F ≥ 2 stage fibrosis assessed by TE were 6.6 kPa, for acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) 1.22 m/s, for APRI 0.75 and for FIB-4 1.47. For F ≥ 3 TE was 8.9 kPa, ARFI was 1.48 m/s, APRI was 0.75, and FIB-4 was 2. For F = 4, TE was 12.2 kPa, ARFI was 1.77 m/s, APRI was 1.46, and FIB-4 was 3.91. The APRI could not distinguish between F2 and F3, P = 0.92. The negative predictive value for F = 4 for TE and ARFI was 100%. Kappa index values for F ≥ 3 METAVIR score for TE, ARFI and FIB-4 were 0.687, 0.606 and 0.654, respectively. This demonstrates strong concordance between all three screening methods, and moderate to strong concordance between them and APRI (Kappa index = 0.507).

CONCLUSION

Given the costs and accessibility of LSM methods, and the similarity with the outcomes of SM, we suggest that FIB-4 as well as TE and ARFI may be useful indicators of the degree of liver fibrosis. This is of particular importance to developing countries.

Keywords: Elastography, Serum markers, Hepatitis C virus, Liver stiffness, Liver biopsy

Core tip: Liver fibrosis evaluation in hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients has critical impact on prognosis and treatment strategies. Despite liver biopsy (LB) remains the gold standard for its evaluation, non invasive methods has improved in recent years. We evaluated 81 HCV patients with elastography methods [Fibroscan and acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI)] and serum markers (APRI and FIB-4) compared to LB, and found that Fibroscan, ARFI, and FIB-4 independently identify advanced fibrosis. We suggest that FIB-4 alongside Fibroscan and ARFI may be good tools for the prediction of severity of liver fibrosis. This may be of particular importance to developing countries.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is one of the most frequent etiologies of cirrhosis, and is therefore responsible for most of its complications, including hepatocellular carcinoma, which is the sixth most common cancer worldwide[1]. Despite the recent advances in HCV therapy, the prevalence of advanced liver disease will continue to increase as well as the corresponding healthcare burden[2]. In Brazil, although the hepatitis C viremic prevalence is about 1%, only 15% of the estimated infected patients are diagnosed, usually with advanced fibrosis. This is partly explained by the scarcity of specialist centers compared with the societal needs. Of those who are diagnosed, only 60% receive specialized treatment[3,4].

The stage of liver fibrosis in HCV patients is associated with prognosis, and has a resulting impact on treatment strategy and follow-up. Liver biopsy (LB) is still the gold standard procedure for fibrosis assessment, but non-invasive new approaches have been strongly recommended for evaluation of fibrosis, mainly in HCV. They require less operator expertise, have no complications and have good diagnostic accuracy[5-7]. The most extensively used non-invasive mechanical methods based on ultrasound are transient elastography (TE or FibroScan®) and acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) technology, Virtual Touch®. There are several laboratorial markers in development, and validated scores such as aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) and FIB-4 [based on age, platelet count, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT)], that are easily calculated with routine laboratory tests.

Use of liver biopsy has decreased following the introduction of non-invasive tests, especially among chronic HCV patients[8]. Although, according to the recently published EASL Guideline for the evaluation of HCV patients, a perfect marker (AUROC > 0.90) for liver disease could not be achieved, the use of non-invasive tests reduce, but do not abolish the need for liver biopsy[8].

Many biological tests, including APRI, PGA index, Forns’ index, Fibrotest, FIB-4 and Hepascore have been compared with TE and/or ARFI and LB for initial evaluation of liver fibrosis in HCV patients[9]. They have compared favorably, although some are difficult to calculate and others use specialized expensive commercially produced markers. However, APRI and FIB-4 are more accessible and easier to apply than others. As TE and ARFI show a representative result of different parts of the liver, accuracy studies have been developed to evaluate performance compared to LB, which evaluates only a small sample of the liver. As the best cut-off points of each fibrosis stage varies according to different cirrhosis etiologies and populations, these cut-off points need to be validated.

The aim of this study is to identify optimal cutoff values for TE, ARFI, APRI and FIB-4 compared with LB in a Brazilian HCV cohort, according to levels of significant fibrosis (F ≥ 2), advanced fibrosis (F ≥ 3) and cirrhosis (F = 4).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical considerations

The Ethics Committee of the Hospital das Clínicas (CAPPesq number 1276/09) reviewed and approved this study, that was conducted following the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed written consent was waived.

Study design

We performed an observational study of diagnostic accuracy for TE, ARFI, APRI and FIB-4 compared with LB. Between 2012 and 2014, 123 consecutive HCV patients followed by Hepatology Outpatient Center of Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo School of Medicine, Brazil, that would be submitted to liver biopsy had liver stiffness measurement (LSM) [FibroScan®, EchoSens, Paris, France)/ARFI, Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) and serum markers (SM) [FIB-4/APRI] exams done, in order to compare the data with METAVIR score.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) HCV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) RNA positivity for at least 6 mo, and clinical or histopathological diagnosis of chronic HCV; and (2) representative liver biopsy (minimum of 10 portal spaces, non subcapsular fragment) carried out until 30 d prior to LSM and SM. Exclusion criteria were: (1) patient under 18 years of age; (2) hepatitis B virus (HBV) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) co-infection; (3) other chronic liver disease (cholestasis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease); (4) decompensated cirrhosis; (5) biopsies performed for more than 30 d of the evaluation; and (6) non-representative liver biopsy.

Results from TE and ARFI® were blinded for the results from LB. FibroScan® and ARFI were performed by an experienced ultrasonographist with more than 80000 liver ultrasounds, more than 2000 FibroScan® and more than 2000 ARFIs.

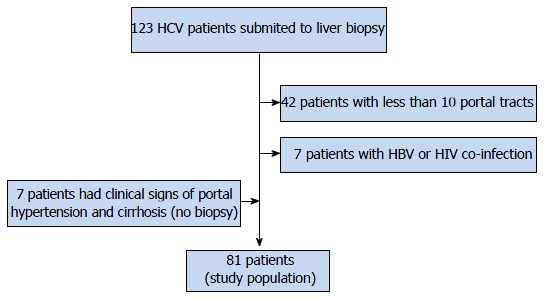

Forty-nine patients were excluded, as shown in Figure 1. Seven patients without LB, but with clinical signs of portal hypertension and cirrhosis (Metavir F = 4) were included. In the end, 81 were selected for the study. Three patients had hepatocellular carcinoma, with less than 2 cm. They were included in the study.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study population enrollment. HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus.

Clinical and biological data

Anthropometric, clinical and laboratorial data were collected: Gender, age, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol consumption, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and serum enzymes such as AST, ALT, bilirubin, albumin, glucose levels and platelet count, all taken from medical charts.

Transient elastography

LSM were performed using the FibroScan® 402 device powered by VCTE (EchoSens, Paris, France), equipped with the standard M probe. The examination procedure have been previously described[9-11]. A valid LSM examination included 10 valid measurements, a success rate of 70%, and an interquartile range of measurements (IQR) below 30% of the median value. Controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) was also evaluated.

ARFI

ARFI technology measures the shear wave speed in a precise anatomical region, with a predefined size, provided by the system. Measurement value and depth are also reported and elasticity results are represented in m/s[12]. ARFI elastography was performed using a Siemens Acuson S2000® ultrasound system, a Virtual Touch® quantification elastography technology (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany). The patients were examined in dorsal decubitus, with the right arm in maximum abduction. Scans were performed in a right inferior intercostal space over the right liver lobe (e.g., segment 8), 2 cm under the capsule, with minimal scanning pressure applied by the operator, while patients were asked to stop breathing temporarily. Ten measurements per patient were performed and a median and IQR values were calculated by the machine. Only when an IQR 30% was reached was the median value accepted.

APRI and FIB-4

APRI and FIB-4 were calculated through the following scores: APRI score = {[AST/upper limit of normal (ULN)] 100}/platelet count 109/L. FIB-4 score = {[age (yr) x AST (U/L)] / [platelet count (109/L) x ALT (U/L)]}.

LB

LB was performed in all but 7 patients, who had clinical or ultrasonographic signs of portal hypertension and cirrhosis. They were judged to have Metavir F4 histology. The LB was guided with 14 G - TruCut needle (Medical Technology, Gainsville, FL, United States). LB fragments including at least 10 portal tracts were considered adequate for pathological interpretation, and were included in our study. Liver specimens were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Two micron sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin, Masson’s trichrome and Sirius red for histological assessment. The liver biopsies were assessed according to the METAVIR score, by a senior pathologist and classified as: F0 - no fibrosis; F1 - portal fibrosis without septa; F2 - portal fibrosis and few septa extending into lobules; F3 - numerous septa extending to adjacent portal tracts or terminal hepatic venules and F4 - cirrhosis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using R statistics version 3.2.5. (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). The STARD Statement guidelines were followed. Quantitative characteristics were expressed as mean (SD), median (first and third quartile) and range. Variables were compared using non-parametric Wilcoxon test. P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

The ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for comparison of two or more groups, whether or not the data were normally distributed, respectively. We set that mild disagreement was when only one class was different, and severe disagreement when two or more class were wrongly misclassified.

The diagnostic performance of FibroScan®, ARFI, APRI and FIB-4 tests was assessed using receiver operator curves (ROC). The optimum cut-off levels, defined as area under ROC (AUROC), of each test was chosen to define fibrosis stages F ≥ 2, F ≥ 3 and F = 4. The Kappa index set the concordance analysis. The best sensitivity values (> 80%) have been chosen in order to identify all HCV patients with METAVIR F ≥ 3 (prioritized for treatment according to Brazilian Ministry of Health recommendations)[13]. Positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) were calculated using the prevalence of liver fibrosis stages (F > 2) in the Hepatology Outpatient Center from Hospital das Clinicas of the University of Sao Paulo School of Medicine, Brazil. A statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician (João Ítalo França).

RESULTS

A total of 81 patients with HCV were included, 41 (50.6%) were female. Anthropometric and laboratorial characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 51 years (30-78). Eleven (13.6%) patients had diabetes, 22 (27.2%) hypertension, 20 (24.7%) were smokers and 11 (13.6%) consumed alcohol (> 20 g /d). The median BMI was 26.5 (24.3-29.6), and 70% of the patients were HCV treatment-naïve. Most of the patients had Metavir F1 on LB fibrosis stage (33 patients, 40.7%), followed by F2 (20 patients, 24.7%). The mean success rate of TE was 92%.

Table 1.

Demographic, laboratory and liver fibrosis characteristics

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 81) |

| Gender (male/female) | 40 (49.4%)/41 (50.6%) |

| Age (yr) - median (Q1;Q3) | 51 (30-78) |

| BMI (kg/m2) - median (Q1;Q3) | 26.5 (24.3-29.6) |

| ALT (IU/L) - median (Q1;Q3) | 50 (32.5-85) |

| AST (IU /L) - median (Q1;Q3) | 42 (28.5-61.5) |

| Platelet count (× 103/mm3) - median (Q1; Q3) | 202 (148-247) |

| Histological fibrosis stage, n (%) | |

| F0 | 5 (6.2) |

| F1 | 33 (40.7) |

| F2 | 20 (24.7) |

| F3 | 12 (14.8) |

| F4 | 11 (13.6) |

| TE (kPa) - median (Q1; Q3) | 6.9 (5-12.2) |

| TE success rate (mean ± SD) | 0.92 ± 0.21 |

| CAP (dB/m) - mMedian (Q1; Q3) | 237 (204-263) |

| ARFI (m/s) - median (Q1; Q3) | 1.25 (0.65-2.89) |

| APRI - median (Q1; Q3) | 0.66 (0.41-1.29) |

| FIB-4 - median (Q1; Q3) | 1.41 (0.90-2.45) |

BMI: Body mass index; ALT: Alanine amino transferase; AST: Aspartate amino transferase; TE: Transient elastography; CAP: Controlled attenuation parameter; ARFI: Acoustic radiation force impulse; APRI: Score index (AST/LSN AST/platelet); FIB-4: Score index (age × AST/platelet × ALT).

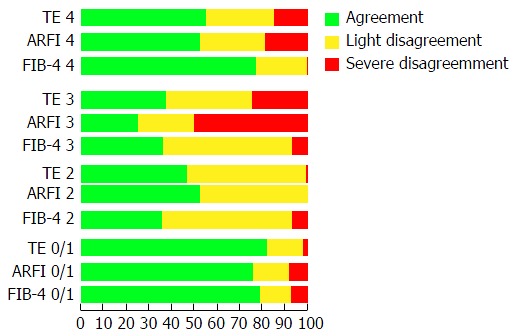

The best cut-off values of each test (LSM and SM) are found in Table 2. For predicting F ≥ 2 stage fibrosis with TE was 6.6 kPa, for ARFI 1.22 m/s, for APRI 0.75 and for FIB-4 1.47. For F ≥ 3, TE was 8.9 kPa, ARFI was 1.48 m/s, APRI was 0.75, and FIB-4 was 2. For F = 4, TE was 12.2 kPa, ARFI was 1.77 m/s, APRI was 1.46, and FIB-4 was 3.91. The APRI could not distinguish between F2 and F3 (P = 0.92). The NPV for F = 4 for TE and ARFI was 100%. Kappa Index values for F ≥ 3 METAVIR score for TE, ARFI and FIB-4 were 0.687, 0.606 and 0.654, respectively. This demonstrates strong concordance between the TE, ARFI and FIB-4 methods, but moderate concordance between them and APRI (Kappa index = 0.507). Figure 2 shows the rate of agreement of TE, ARFI, APRI and FIB-4 according to Metavir stage on LB. Since alcohol consumption and severity of liver inflammation could affect TE measurements, patients were also analyzed individually. Of the 11 patients with alcohol consumption, 2 patients had discordant results between TE and liver biopsy. One had Metavir F1A1 and TE of 10 kPa and the other had Metavir F1A2 and TE of 16.3 kPa. With regard to patients with more intense inflammatory activity on hepatic biopsy (Metavir A3-4), we had 6 patients with Metavir A3, and none with Metavir A4. Of these Metavir A3 patients, 5 were Metavir F3 and 1 had cirrhosis. TE discordance with liver biopsy could be found in all Metavir F3A3 patients, with overestimation of TE results (mean TE results: 25.3 kPa). One Metavir F3A3 patient had ALT of 148 U/L and a TE of 28.4 kPa. All other patients with Metavir F3A3 had ALT results between 32 and 86 U /L.

Table 2.

Summary of cut-off values, area under de curve, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy

| Method | AUC | AUC CI (95%) | Se | Sp | PPV | NPV | Accuracy |

| TE (kPa) | |||||||

| > F2 (6.6) | 0.8716 | 0.7953-0.948 | 82.90% | 77.50% | 89.30% | 66.70% | 80.20% |

| > F3 (8.9) | 0.9187 | 0.8319-1.000 | 87% | 86.20% | 87.30% | 85.90% | 86.40% |

| = F4 (12.2) | 0.9675 | 0.9321-1.000 | 100% | 87.10% | 79.30% | 100% | 88.90% |

| ARFI (m/s) | |||||||

| > F2 (1.22) | 0.7701 | 0.6653-0.8749 | 78% | 70% | 85.50% | 58.40% | 74.10% |

| > F3 (1.48) | 0.8669 | 0.7756-0.9583 | 82.60% | 82.80% | 83.90% | 81.40% | 82.70% |

| = F4 (1.77) | 0.9188 | 0.8592-0.9784 | 100% | 85.70% | 77.50% | 100% | 87.70% |

| APRI | |||||||

| > F2 (0.75) | 0.8107 | 0.7136-0.9077 | 75.60% | 87.50% | 93.20% | 61.30% | 81.50% |

| > F3 (0.75) | 0.8272 | 0.7140-0.9405 | 87% | 72.40% | 77.40% | 83.60% | 76.50% |

| = F4 (1.46) | 0.9143 | 0.8387-0.9899 | 81.80% | 90% | 80.10% | 91% | 88.90% |

| FIB-4 | |||||||

| > F2 (1.47) | 0.8652 | 0.7844-0.9461 | 78% | 82.50% | 91% | 62.40% | 80.20% |

| > F3 (2.0) | 0.8703 | 0.7634-0.9773 | 82.60% | 86.20% | 86.70% | 82% | 85.20% |

| = F4 (3.91) | 0.9636 | 0.9211-1.000 | 90.90% | 95.70% | 91.30% | 95.50% | 95.10% |

AUC: Area under de curve; CI: Confidence interval; Se: Sensitivity; Sp: Specificity; PPV: Positive predictive value; NPV: Negative predictive value.

Figure 2.

Rate of agreement of transient elastography, acoustic radiation force impulse, aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index and FIB-4 according to Metavir fibrosis stage (%). TE: Transient elastography; ARFI: Acoustic radiation force impulse; FIB-4: Score index (age × AST/platelet × ALT).

DISCUSSION

Our results show that three methods, ARFI, TE and FIB-4, independently identify advanced fibrosis. Non-invasive methods have been studied and compared to other methods of liver fibrosis evaluation in order to diminish complications of liver biopsy and costs involved[8]. We evaluated the AUROC and the inter-agreement of LSM (TE and ARFI) as well as SM (APRI and FIB-4) compared with liver biopsy in a population of HCV-infected patients. The best cut-offs were established based on METAVIR fibrosis stages F ≥ 2, F ≥ 3 and F = 4, considering not only the recent international consensus (EASL-ALEH 2015) but the recommendation for HCV treatment in Brazil, which prioritize F ≥ 3 patients according to the 2015 Brazilian Protocol for HCV treatment[4,8,13]. The results of this study do not conflict with previous findings (Table 2). The TE sensitivity (Se) and specificity (Sp) in a recent FibroScan® meta-analysis[14] ranged from about 0.70 and 0.81 for F ≥ 2, 0.80 and 0.85 for F ≥ 3, and from 0.86 and 0.88 for F = 4. These are similar to our results. Although TE had better results for F ≥ 2, the overall accuracy for ARFI and TE were comparable, as previously demonstrated by Crespo et al[15]. For the F4 group we found an almost perfect correlation between ARFI, TE and FIB-4, suggesting that only one method is sufficient to identify cirrhosis. It is important to note that on 2 out of 11 patients who reported alcohol consumption (> 20 g/d), TE values were overestimated. The influence of alcohol intake on liver stiffness measurement should be taken into account when interpreting TE results, as shown by Bardou-Jacquet et al[16]. Hepatic inflammation can also be a confounding factor when evaluating liver fibrosis by TE[17]. We could demonstrate that all Metavir F3A3 patients had overestimation of liver fibrosis by TE, with median values of 25.3 kPa.

APRI is a good reproducible marker of cirrhosis, with a high applicability (> 95%), it is easy to perform and is a non-patented score[18]. In our study APRI could not differentiate between F = 2 and F = 3. This is possibly because it uses fewer variables than FIB-4. APRI uses AST and platelet count, while FIB-4 also incorporates ALT and age of the patient.

The F2 group is less clearly defined than other stages of fibrosis, as shown in the literature by Rizzo et al[19], and all methods identified it less accurately. In our study however, there was less disagreement than Afdhal et al[20] which shows that for F2 group, application of both methods, TE and ARFI are necessary to identify these patients.

Although LB is the reference standard, its reproducibility is poor, owing to heterogeneity in liver fibrosis, operator bias and sample size. This can account for an margin of error of up to 20% in disease staging[20].

A limitation of this study is that it identifies and selects cut-off points, but is not prospectively validated, warranting further studies to confirm these results. However, from this study, we can consider that a combined use of FibroScan® and FIB-4 or FibroScan® and ARFI in the follow-up of HCV patients can be a surrogate for fibrosis assessment through LB, which can be held in reserve for cases with significant diagnostic doubt. This is especially important in the intermediate stages of fibrosis (F2 and F3), where each individual non-invasive method is not sufficiently accurate to make a diagnosis, and so should be performed in combination. Further studies are necessary to identify whether they should be performed simultaneously or in parallel, and identify the best cutoffs for each combination of methods.

In conclusion, given the higher cost and reduced accessibility of LSM methods, and the similarity with the outcomes of SM in evaluation of liver fibrosis, we suggest that FIB-4 used alongside TE and ARFI may be good tools for the prediction of severity of liver fibrosis. This may be of particular importance to developing countries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Mr. João Ítalo França, for his generous statistical advice for this manuscript and to Mr. Justin Axelberg, for assistance in editing the manuscript. Special acknowledgments to Alves de Queiroz Family Fund for Research.

COMMENTS

Background

The evaluation of liver fibrosis is not a simple task and demands the use of different methods. Liver stiffness measurement (LSM) and serum markers (SM) provide a non-invasive source of diagnosis with good correlation with the gold standard method, liver biopsy.

Research frontiers

The F2 group is less clearly defined than other stages of fibrosis. In the authors’ study there was however less disagreement, which shows that for F2 group, application of both methods, transient elastography (TE) and acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) is necessary to identify these patients. Further studies are necessary to identify whether they should be performed simultaneously or in parallel, and identify the best cutoffs for each combination of methods.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This results show that three methods, ARFI, TE and FIB-4, independently identify advanced fibrosis.

Applications

Given the higher cost and reduced accessibility of LSM methods, and the similarity with the outcomes of SM in evaluation of liver fibrosis, the authors suggest that FIB-4 used alongside TE and ARFI may be good tools for the prediction of severity of liver fibrosis. This may be of particular importance to developing countries.

Terminology

Non-invasive tests for liver fibrosis evaluation: (1) Mechanical markers: liver stiffness measurement according to transient elastography (FibroScan®) or ARFI; and (2) Serum markers: Aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) and FIB-4 (based on age, platelet count, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase). Liver biopsies were assessed according to the METAVIR score classified as: F0 - no fibrosis; F1 - portal fibrosis without septa; F2 - portal fibrosis and few septa extending into lobules; F3 - numerous septa extending to adjacent portal tracts or terminal hepatic venules and F4 - cirrhosis.

Peer-review

This study is addressed to evaluate the diagnostic performance and the concordance of different noninvasive methods for the evaluation of liver fibrosis (APRI, FIB-4, transient elastography, ARFI) in 81 patients with chronic hepatitis C, most of them with biopsy-proven diagnosis. The authors concluded that FIB-4, ARFI and transient elastography are useful tests for the noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis, with a good concordance.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the CAPPesq, the Ethics Committee for researches of the institution (CAAE number: 1276/09).

Informed consent statement: Institutional review board approval was obtained and the requirement for informed written consent was waived.

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: October 12, 2016

First decision: December 13, 2016

Article in press: February 13, 2017

P- Reviewer: Vanni E S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

References

- 1.Blachier M, Leleu H, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Valla DC, Roudot-Thoraval F. The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. J Hepatol. 2013;58:593–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Razavi H, Elkhoury AC, Elbasha E, Estes C, Pasini K, Poynard T, Kumar R. Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) disease burden and cost in the United States. Hepatology. 2013;57:2164–2170. doi: 10.1002/hep.26218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dore GJ, Ward J, Thursz M. Hepatitis C disease burden and strategies to manage the burden (Guest Editors Mark Thursz, Gregory Dore and John Ward) J Viral Hepat. 2014;21 Suppl 1:1–4. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castro R, Perazzo H, Grinsztejn B, Veloso VG, Hyde C. Chronic Hepatitis C: An Overview of Evidence on Epidemiology and Management from a Brazilian Perspective. Int J Hepatol. 2015;2015:852968. doi: 10.1155/2015/852968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frulio N, Trillaud H, Perez P, Asselineau J, Vandenhende M, Hessamfar M, Bonnet F, Maire F, Delaune J, De Ledinghen V, et al. Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) and Transient Elastography (TE) for evaluation of liver fibrosis in HIV-HCV co-infected patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:405. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bota S, Herkner H, Sporea I, Salzl P, Sirli R, Neghina AM, Peck-Radosavljevic M. Meta-analysis: ARFI elastography versus transient elastography for the evaluation of liver fibrosis. Liver Int. 2013;33:1138–1147. doi: 10.1111/liv.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piscaglia F, Marinelli S, Bota S, Serra C, Venerandi L, Leoni S, Salvatore V. The role of ultrasound elastographic techniques in chronic liver disease: current status and future perspectives. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Association for Study of Liver; Asociacion Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Higado. EASL-ALEH Clinical Practice Guidelines: Non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:237–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castéra L, Vergniol J, Foucher J, Le Bail B, Chanteloup E, Haaser M, Darriet M, Couzigou P, De Lédinghen V. Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:343–350. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandrin L, Fourquet B, Hasquenoph JM, Yon S, Fournier C, Mal F, Christidis C, Ziol M, Poulet B, Kazemi F, et al. Transient elastography: a new noninvasive method for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29:1705–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziol M, Handra-Luca A, Kettaneh A, Christidis C, Mal F, Kazemi F, de Lédinghen V, Marcellin P, Dhumeaux D, Trinchet JC, et al. Noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis by measurement of stiffness in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:48–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.20506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sporea I, Sirli R, Bota S, Fierbinţeanu-Braticevici C, Petrişor A, Badea R, Lupşor M, Popescu A, Dănilă M. Is ARFI elastography reliable for predicting fibrosis severity in chronic HCV hepatitis? World J Radiol. 2011;3:188–193. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v3.i7.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas para Hepatite C e Coinfecções/ Ministério da Saúde. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2015.88p. Available from: http://www.aids.gov.br/

- 14.Tsochatzis EA, Gurusamy KS, Ntaoula S, Cholongitas E, Davidson BR, Burroughs AK. Elastography for the diagnosis of severity of fibrosis in chronic liver disease: a meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. J Hepatol. 2011;54:650–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crespo G, Fernández-Varo G, Mariño Z, Casals G, Miquel R, Martínez SM, Gilabert R, Forns X, Jiménez W, Navasa M. ARFI, FibroScan, ELF, and their combinations in the assessment of liver fibrosis: a prospective study. J Hepatol. 2012;57:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bardou-Jacquet E, Legros L, Soro D, Latournerie M, Guillygomarc’h A, Le Lan C, Brissot P, Guyader D, Moirand R. Effect of alcohol consumption on liver stiffness measured by transient elastography. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:516–522. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i4.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arena U, Vizzutti F, Corti G, Ambu S, Stasi C, Bresci S, Moscarella S, Boddi V, Petrarca A, Laffi G, et al. Acute viral hepatitis increases liver stiffness values measured by transient elastography. Hepatology. 2008;47:380–384. doi: 10.1002/hep.22007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin ZH, Xin YN, Dong QJ, Wang Q, Jiang XJ, Zhan SH, Sun Y, Xuan SY. Performance of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the staging of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: an updated meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2011;53:726–736. doi: 10.1002/hep.24105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rizzo L, Calvaruso V, Cacopardo B, Alessi N, Attanasio M, Petta S, Fatuzzo F, Montineri A, Mazzola A, L’abbate L, et al. Comparison of transient elastography and acoustic radiation force impulse for non-invasive staging of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:2112–2120. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Afdhal NH. Diagnosing fibrosis in hepatitis C: is the pendulum swinging from biopsy to blood tests? Hepatology. 2003;37:972–974. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]