Abstract

The pro-inflammatory mediator leukotriene B4 (LTB4) is implicated in the pathologies of an array of diseases and thus represents an attractive therapeutic target. The enzyme leukotriene A4 hydrolase (LTA4H) catalyses the distal step in LTB4 synthesis and hence inhibitors of this enzyme have been actively pursued. Despite potent LTA4H inhibitors entering clinical trials all have failed to show efficacy. We recently identified a secondary anti-inflammatory role for LTA4H in degrading the neutrophil chemoattractant Pro-Gly-Pro (PGP) and rationalized that the failure of conventional LTA4H inhibitors may be that they inadvertently prevented PGP degradation. We demonstrate that these inhibitors do indeed fail to discriminate between the dual activities of LTA4H, and enable PGP accumulation in mice. Accordingly, we have developed novel compounds that potently inhibit LTB4 generation whilst leaving PGP degradation unperturbed. These novel compounds could represent a safer and superior class of LTA4H inhibitors for translation into the clinic.

Leukotriene A4 hydrolase (LTA4H) is an enzyme that classically functions as an epoxide hydrolase to generate leukotriene B4 (LTB4) from leukotriene A4 (LTA4)1,2. This activity operates within an intracellular compartment and is predominantly a function of leukocytes. LTB4 is an extremely pro-inflammatory lipid mediator that can exert its activity by binding to receptors BLT1 or BLT23. LTB4 can drive the recruitment and activation of an array of cells including neutrophils and is thus implicated in protection against invading micro-organisms but also in the pathology of an array of diseases4,5,6,7,8.

Recently, we identified a secondary anti-inflammatory activity for LTA4H whereby it functions as an aminopeptidases to degrade the tripeptide Pro-Gly-Pro (PGP)9. PGP is a neutrophil chemoattractant derived from extracellular matrix (ECM) collagen via the sequential enzymatic activity of matrix metalloproteinases and prolylendopeptidase10. PGP functions as a neutrophil chemoattractant by mimicking key sequences found in glutamic acid, leucine, arginine+ (ELR+) chemokines and binding to CXCR1/211. Since neutrophils are themselves a prominent source of the enzymes that generate PGP, it is thought that this pathway can drive a self-sustaining vicious circle of inflammation if left unchecked12. We have demonstrated that PGP is readily degraded during episodes of acute pulmonary inflammation by extracellular LTA4H to facilitate the resolution of neutrophilic inflammation, and failure of this system culminated in augmented and prolonged inflammation with exacerbated pathology and illness9,13.

Significant quantities of PGP are found in patients with chronic neutrophilic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Cystic Fibrosis (CF) and bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), peaking with exacerbation of disease and inversely correlating with lung function10,11,14,15,16,17. Accordingly, it seems that the LTA4H-PGP degradation pathway is perturbed in these chronic diseases to enable PGP to accumulate and drive inflammation9,15,18. Together, these studies highlight the critical importance of the secondary PGP-degrading activity of LTA4H.

LTA4H therefore represents a highly unusual enzyme with dichotomous and directly opposing pro- and anti-inflammatory activities that dictate the amplitude and persistence of neutrophilic inflammation19. The enzyme itself is folded into 3 domains, which manifest as N-terminal, catalytic and C-terminal domains20. The interface of these domains forms an L-shaped cavity where the active site of the enzyme is located. The opening part of this cavity, near the protein surface, is wider and highly hydrophilic before narrowing at the site of the catalytic zinc into a predominantly hydrophobic tunnel that penetrates deeper into the protein. The wider hydrophilic part of the cavity is the site of peptide binding, whereas LTA4 occupies the entire cavity with its epoxide coordinating with the zinc and its long hydrophobic tail extending down into the apolar tunnel. It is clear therefore that the opposing activities of LTA4H reside within distinct yet overlapping active sites, with specific amino acid residues required for each21,22.

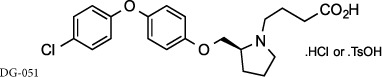

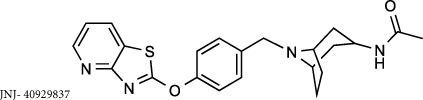

There has been significant interest from pharmaceutical companies to target LTA4H therapeutically to alleviate LTB4-mediated pathologies, but despite the generation of several excellent inhibitors, these drugs have failed to demonstrate clinical efficacy or have been withdrawn from trials owing to deleterious side effects23,24. It is feasible that the lack of success of these compounds may be due to their failure to distinguish between the opposing roles of LTA4H and thus inadvertently prevent PGP degradation. Searle/Pharmacia developed the potent, orally active inhibitor SC567461A that entered clinical trials for inflammatory bowel disease, but was withdrawn owing to adverse outcomes25,26,27. DeCODE pharmaceuticals subsequently utilized a fragment based drug discovery program to identify inhibitors of LTA4H, leading to the development of the potent, orally active compound DG-051 that entered phase IIa clinical trials for myocardial infarction and stroke before further development being precluded28,29,30. More recently, Johnson & Johnson developed potent, orally active benzothiazole derivatives as LTA4H inhibitors31,32,33 leading to the assessment of JNJ-40929837 in a bronchial allergen challenge model of asthma24. Despite JNJ-40929837 demonstrating clear target engagement and reducing LTB4, this drug again failed to show any clinical benefit over placebo24.

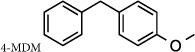

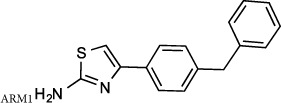

Some studies have previously proposed that it is feasible to develop compounds that can selectively distinguish between the dual activities of LTA4H. Lai and colleagues suggested that diphenyl ether derivatives were capable of augmenting aminopeptidase activity against a synthetic Ala-p-nitroanilide substrate34. Accordingly, Paige and Shim have demonstrated that 4-methoxy diphenylmethane (4-MDM) augmented the aminopeptidase activity of LTA4H and conferred therapeutic benefit in murine models of emphysema35,36. Conversely, Haeggstrom and colleagues have suggested that it is feasible to selectively inhibit the epoxide hydrolase activity whilst leaving the aminopeptidase activity unperturbed, demonstrating that the molecule 4-(4-benzylphenyl) thiazol-2 amine (ARM1) could inhibit LTB4 generation without affecting PGP degradation37.

In this study, we have utilized robust, physiologically relevant assays to provide a definitive side-by-side comparison of existing classes of LTA4H modulators and develop novel selective compounds. We demonstrate that existing LTA4H inhibitors that have entered the clinic are equipotent at inhibiting both LTB4 generation and PGP degradation and in vivo administration can consequently result in PGP accumulation. We highlight the necessity of using the physiological substrate, PGP, when evaluating the aminopeptidase activity of LTA4H; with diphenyl ether derivatives failing to boost PGP cleavage as has been reported with an alternative Ala-p-nitroanilide substrate. Finally, we have developed two distinct chemical series of compounds that can selectively inhibit LTB4 generation with a selectivity that is superior to that of ARM1. These novel compounds could form the basis for the development of selective and safer therapeutics for targeting LTA4H in a broad array of disease modalities.

Results

A rational approach to selective LTA4H inhibitor design

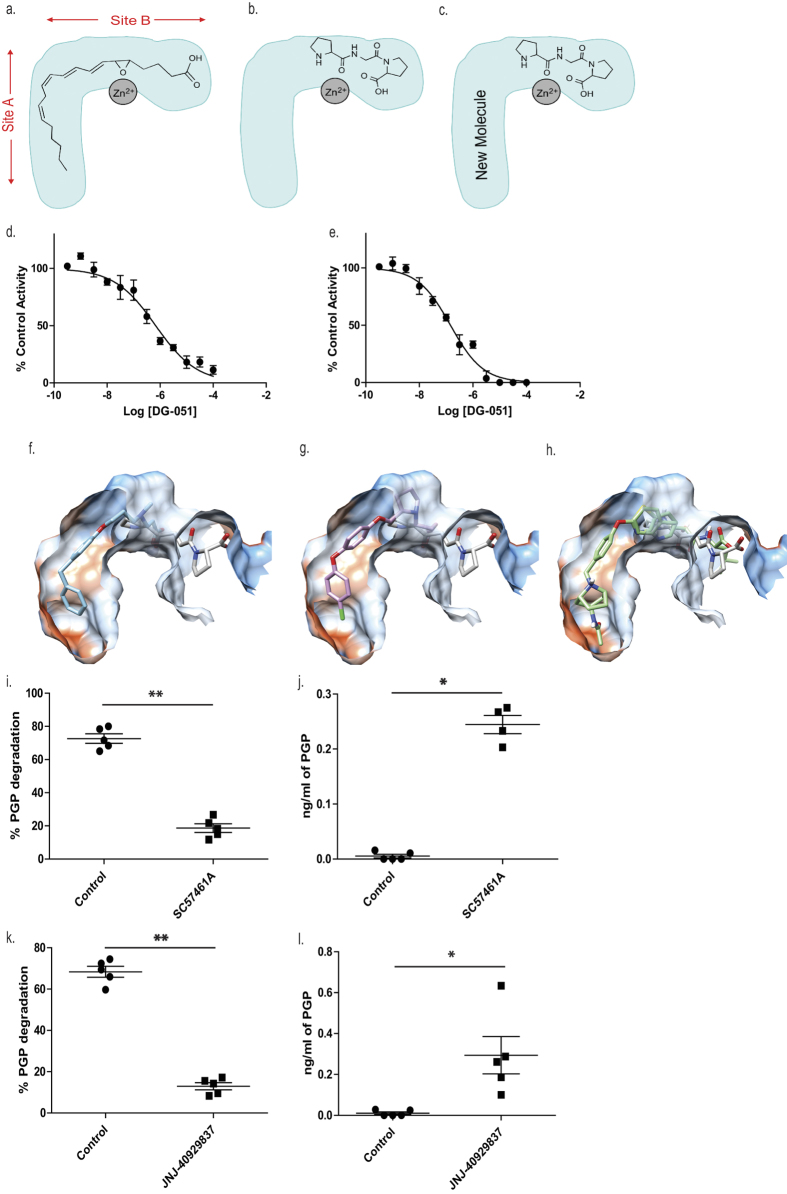

Previous studies that have aimed to develop potent LTA4H inhibitors have largely failed to consider the physiological significance of the recently identified anti-inflammatory aminopeptidase activity. It is apparent that the two activities of LTA4H occur via distinct but overlapping active sites, both located in a deep L-shaped cleft. One arm of this cleft is narrow and hydrophobic (Site A; Fig. 1a) and the other contains the zinc-binding site (Site B; Fig. 1a). LTA4 fills the entire cavity, with its hydrophobic tail buried in one arm and the zinc chelated to the epoxide in the other arm (Fig. 1a). In contrast, aminopeptidase PGP-degrading activity appears confined to the zinc-containing arm (Fig. 1b). We hypothesized that whilst conventional LTA4H inhibitors would occupy both sites it would be preferable to develop molecules to bind to one of the two overlapping binding sites (Site A) present in LTA4H, leaving Site B free to bind PGP (Fig. 1c). This should block detrimental hydrolase activity, whilst preserving beneficial peptidase function.

Figure 1. LTA4H inhibitors to have entered the clinic are non-selective and inhibit PGP degradation in vitro and in vivo.

Schematic representation of the binding site of LTA4H showing the relative positions occupied by LTA4 (a) and PGP (b). (c) Proposed solution for a new compound that sits in the narrow arm occupied by the hydrophobic tail of LTA4, (Site A) blocking its hydrolysis, but retaining ability to cleave the tripeptide PGP (Site B). The capacity of DG-051 to inhibit LTA4H epoxide hydrolase (LTB4 generation; (d)) and aminopeptidase activities (PGP degradation; (e)). Overlay of the X-ray structures of ligand-LTA4H structures of (f) SC57461 (blue; 3U9W.pdb) and (g) DG-051 (pink; 3FH7.pdb) with that of the stable PGP analogue OBP-Pro (white, 4MS6.pdb). The protein surface is coloured by amino acid hydrophobicity from most hydrophobic (orange) to hydrophilic (blue) through white regions. (h) JNJ-40929837 (green) was docked into the protein with Autodock Vina. Mice were orally administered SC57461A (i and j) or JNJ-40929837 (k and l) and serum aminopeptidase activity (i and k) or absolute PGP concentrations (j and l) were determined. IC50 curves were generated from 3 technical replicates at each concentration of test compound and at least 2 biological replicates. Data for in vivo studies (i–l) are representative of 2 experiments with 5 mice per group. Results depicted as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 using Mann–Whitney statistical test.

Conventional LTA4H inhibitors that have entered the clinic are non-selective and inhibit PGP degradation

To validate our hypothesis that conventional LTA4H inhibitors fail to distinguish between the dual activities of the enzyme, we synthesized SC57461A, DG-051 and JNJ-40929837 and assessed their capacity to inhibit LTB4 generation and PGP degradation. In keeping with previous literature, all were potent inhibitors of LTA4H epoxide hydrolase activity in a murine neutrophil-based assay (Table 1; Fig. 1d for representative IC50 curve for DG-051). However, each of these compounds was also comparably potent at inhibiting the aminopeptidase activity of recombinant LTA4H against the PGP substrate (Table 1; Fig. 1e for representative IC50 curve for DG-051). This lack of selectivity can be rationalized by examining published X-ray data of LTA4H bound to SC57461A (3U9W.pdb) and DG-051 (3FH7.pdb) with that of 1-{4-oxo-4-[(2S)-pyrrolidin-2-yl]butanoyl}- L-proline (OBP-Pro), a stable PGP analogue (4MS6.pdb). In all cases the structure of the protein is highly conserved (rms 0.28–0.35 Å over 611 atoms) and focussing on the active site of the enzyme shows that both SC57461A (Fig. 1f) and DG-051 (Fig. 1g) encroach into the zinc binding arm (Site B) that OBP-Pro, and by analogy PGP, occupies. Docking JNJ-40929837 into the same site (Fig. 1h) demonstrates that this compound fills both arms, again suggesting it will impede PGP binding. It has previously been demonstrated that oral administration of SC57461A or a JNJ-40929837 derivative to naïve mice resulted in a potent inhibition of LTB4 generation in an ex vivo whole blood assay25,31. Importantly, we demonstrate that a comparable protocol, whereby SC57461A or JNJ-40929837 are orally administered to naïve mice, also potently abrogates serum aminopeptidase PGP-degrading activity (Fig. 1i and k, respectively) and leads to serum accumulation of PGP (Fig. 1j and l, respectively). These studies highlight the potential inherent risk of these potent, yet non-selective, LTA4H inhibitors.

Table 1. Effect of LTA4H inhibitors to have entered the clinic and purportedly selective modulators on inhibition (IC50) of the epoxide hydrolase (LTB4 generation) and aminopeptidase (PGP degradation) activities of LTA4H in our assays, as described in Materials and methods.

| Compound | Epoxide Hydrolase IC50 ± SEM (nM) | Aminopeptidase IC50 ± SEM (nM) |

|---|---|---|

|

110 ± 23.5 | 74 ± 7.3 |

|

680 ± 10.0 | 150 ± 19.4 |

|

9.0 ± 0.09 | 9.4 ± 1.3 |

|

48,900 ± 9,538 | 75,210 ± 9,752 |

|

600 ± 66.2 | 9,110 ± 1,092 |

IC50 curves were generated from 3 technical replicates at each concentration of test compound and at least 2 biological replicates. Results depicted as mean ± SEM.

Diphenyl ether derivatives fail to augment LTA4H aminopeptidase activity when utilizing the physiological substrate PGP

Previous reports have cited the potential of simple diphenyl ether derivatives to enhance aminopeptidase activity in assays using chromogenic synthetic peptide substrates34. The compound 4-MDM exemplifies this class of compounds, being demonstrated to augment aminopeptidase activity versus an Ala-p-nitroanilide substrate with an AC50 of 50 μM35. In our hands, whilst 4-MDM did promote aminopeptidase activity versus an Ala-p-nitroanilide substrate, this augmentation was not observed when utilizing the physiological substrate PGP; with modest inhibition even apparent (Table 1). The size and structural differences between PGP and Ala-p-nitroanilide substrates may result in their altered occupancy and positioning within the active site of LTA4H, and rationalize the differences observed in the behaviour of 4-MDM. However, these studies clearly demonstrate the importance of utilizing a physiological substrate rather than one that facilitates high throughput screening and suggest that diphenyl ether derivatives do not offer a promising chemical starting point as a generation of selective LTA4H modulators.

Development of selective LTA4H inhibitors to specifically target LTB4 generation

Haeggstrom and colleagues recently identified ARM1 as a potential selective LTA4H inhibitor, with the capacity to inhibit LTB4 generation without perturbing PGP hydrolysis. They demonstrated that ARM1 efficiently inhibited LTB4 production by neutrophils with an IC50 of 0.5 μM without significantly compromising PGP degradation37. In our cell based system, ARM1 exhibited a comparable capacity to inhibit LTB4 generation (Table 1). However, whilst we did confirm a distinct selectivity of ARM1 in inhibiting the epoxide hydrolase activity over the aminopeptidase activity, this compound was, in our hands, capable of inhibiting PGP degradation with an IC50 of around 9.1 μM (Table 1). In publishing the X-ray crystallography structure of ARM1 within the active site of LTA4H, the authors report two potential orientations of the compounds located within Site A portraying some fluidity in binding. Our docking analysis of ARM1 within the active site of LTA4H revealed one of six poses where the compound sits in the peptide binding site (Supplementary Figure S1) – which may rationalize the partial inhibition of this activity.

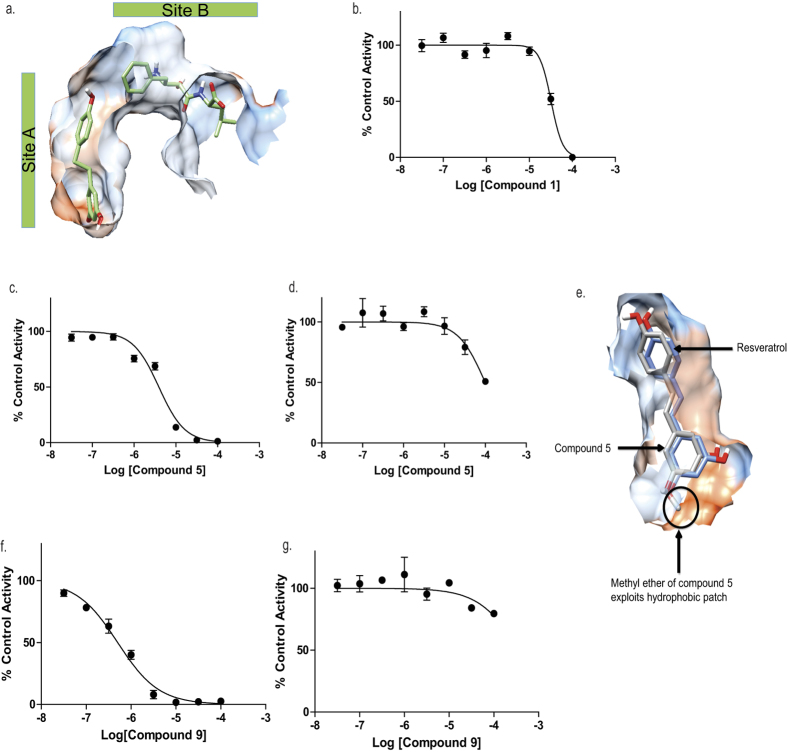

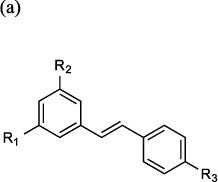

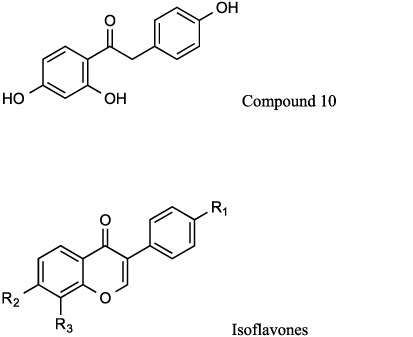

Resveratrol-based compounds to selectively target LTA4H

A published X-ray structure of LTA4H (3FTX.pdb) shows two different molecules simultaneously bound in each arm of the active site (Fig. 2a). A molecule of 2H-resveratrol solely occupies our target site (Site A), whilst one of bestatin – a known peptidase inhibitor, occupies the Zn catalytic site (Site B). The molecule resveratrol (compound 1) occupies the same region of the active site (Site A) as 2H-resveratrol, but with its double bond reducing flexibility (3FTS.pdb). In this structure, the R2 phenol hydroxyl of resveratrol makes a key interaction with a hydrophilic patch on the enzyme, encompassing Ser-379, Lys-364 and Asp-312. Thus resveratrol (compound 1) seemingly represented a rational starting point for the development of a novel selective LTA4H inhibitor. In accordance with the binding studies, resveratrol (compound 1) exhibited minimal inhibition of PGP degradation, with negligible inhibition observed at a concentration of 100 μM (Table 2a). Furthermore, this compound exhibited a modest inhibition of LTB4 generation and thus displays some potential to distinguish between the two functions of the enzyme with biased inhibition of the epoxide hydrolase activity (Fig. 2b and Table 2a). An iterative approach of targeted drug design and structure activity relationship studies (SAR) was subsequently utilized to develop compounds based upon the resveratrol core that would exhibit superior inhibition of LTA4H epoxide hydrolase activity whilst maintaining selectivity.

Figure 2. Compounds with a resveratrol core are selective epoxide hydrolase inhibitors.

(a) LTA4H contains two overlapping binding Sites A and B with previous X-ray crystallography studies revealing that two small molecules are capable of binding in each of the sites simultaneously (3FTX.pdb). Peptidase inhibitor Bestatin occupies Site B and 2H-Resveratrol sits in Site A. The protein surface is coloured by amino acid hydrophobicity from most hydrophobic (orange) to hydrophilic (blue) through white regions. LTA4H epoxide hydrolase activity (b,c and f) and aminopeptidase activity (d and g) are presented following treatment with resveratrol (compound 1; b), compound 5 (c and d) and compound 9 (f and g). (e) Site A with docked pose of pinostilbene (compound 5; grey) overlaid on the X-ray structure of 2H-resveratrol bound to LTA4H (blue; 3FTS.pdb). The protein surface is coloured by amino acid hydrophobicity from most hydrophobic (orange) to hydrophilic (blue) through white regions. The methyl ether exploits a hydrophobic patch in Site A, an interaction that is not favoured for Resveratrol and accounts for the increase in activity of compound 5 compared to Resveratrol. IC50 curves were generated from 3 technical replicates at each concentration of test compound and at least 2 biological replicates. Results depicted as mean ± SEM.

Table 2. Effect of (a) analogues of resveratrol (compound 1) and (b) (hydroxyphenyl)ethylphenols on inhibition (IC50) of the epoxide hydrolase (LTB4 generation) and aminopeptidase (PGP degradation) activities of LTA4H as described in Materials and methods.

| Cmpd. No. | R1 | R2 | R3 | Epoxide Hydrolase IC50 ± SEM (μM) | Aminopeptidase IC50 ± SEM (μM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| 1 | OH | OH | OH | 32.2 ± 5.9 | >100 | |||

| 2a | OH | OH | OH | 14.3 ± 2.1 | 85.3 ± 33.9 | |||

| 3 | OMe | OMe | OMe | 41.2 ± 5.5 | 68.8 ± 9.9 | |||

| 4 | OCOMe | OCOMe | OCOMe | 38.6 ± 5.9 | >100 | |||

| 5 | OMe | OH | OH | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 99.5 ± 22.6 | |||

| ||||||||

| Cmpd. No. | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | Epoxide Hydrolase IC50 ± SEM (μM) | Aminopeptidase IC50 ± SEM (μM) | |

| 6 | OMe | OH | H | H | OH | 6.4 ± 0.7 | >100 | |

| 7 | OEt | OH | H | H | OH | 3.2 ± 0.7 | >100 | |

| 8 | OMe | OH | H | OH | H | 1.7 ± 0.25 | >100 | |

| 9 | OMe | OH | OH | H | H | 0.50 ± 0.04 | >100 | |

IC50 curves were generated from 3 technical replicates at each concentration of test compound and at least 2 biological replicates. Results depicted as mean ± SEM.

aZ-isomer.

Changing the configuration of the double bond from trans- (resveratrol; compound 1) to cis- (compound 2) alters both the distance and relative dispositions of the two aromatic rings but seemingly had minimal impact on the compound’s capacity to inhibit epoxide hydrolase or aminopeptidase activities of LTA4H (Table 2a). The results of docking experiments suggest both cis- (compound 2) and trans-resveratrol (compound 1) occupy the desired region (Site A) of the active site with one of the phenol hydroxyls (R2) of both compounds forming an identical interaction with a hydrophilic patch on the enzyme. Blocking all three hydroxyls of trans-resveratrol with methyl ethers (compound 3) or acetyl groups (compound 4) modestly reduced the capacity to inhibit LTB4 generation (Table 2a). However, methylation of a single hydroxyl (R1) gives a compound with significantly increased capacity to inhibit LTB4 generation (compound 5. Figure 2c and Table 2a), whilst still leaving aminopeptidase activity largely unperturbed (Fig. 2d and Table 2a). Docking this molecule into Site A shows that this can be attributed to an interaction with a hydrophobic patch that cannot be exploited by the polar R1 OH of resveratrol (Fig. 2e).

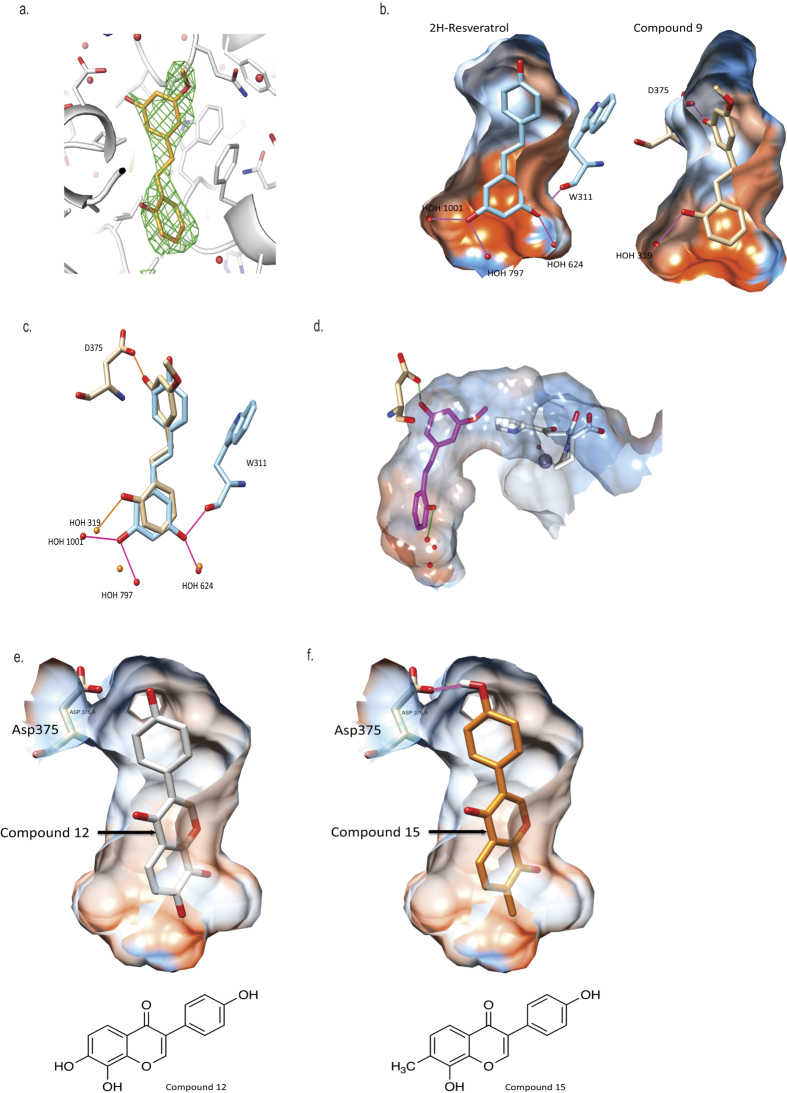

Further modification of compound 5 confirmed that the double bond between the two aromatic rings was not essential for inhibition of epoxide hydrolase activity (compound 6; Table 2b). Moreover increasing the size of the alkyl ether substituent at R1 from methyl to ethyl (compound 7) did not offer any advantage in promoting LTB4 inhibitory capacity (Table 2b). Exploring other regioisomers of compound 6 (Table 2b) highlighted that the positions of the phenolyic hydroxyl groups were not optimal. For example, moving the phenol hydroxyl from the R5- to the R4-position (compound 8) had modest impact on its capacity to inhibit LTB4 generation, but relocation of the hydroxyl to the R3-position (compound 9) augmented the LTB4 inhibitory capacity of the compound 10-fold (IC50 0.5 μM; Fig. 2f and Table 2b), whilst still leaving the aminopeptidase PGP-degrading activity unperturbed (Fig. 2g and Table 2b). The origins of the augmented capacity of compound 9 to inhibit LTA4H epoxide hydrolase activity were explored by modelling and X-ray crystallography (Fig. 3a). The X-ray structure of LTA4H shows high similarity to literature examples (RMSD between 606 atom pairs is 0.204 Å). Of most note, compound 9 has flipped within Site A of the active site of LTA4H relative to 2H-resveratrol (3FTU.pdb) so that the phenolic hydroxyl in the 2-position now forms a hydrogen bond with Asp-375 (Fig. 3b and c) and the two ligands are effectively located head-to-tail. This pose is also present in those generated by in silico docking. Whilst 2H-resveratrol forms two interactions with Trp-311, one H-bond and one π-stack, these are absent in the compound 9 structure, where the 3-methoxy-5-phenol ring rotates to allow the phenol to H-bond to Asp-375 (Fig. 3c). Importantly, previous site-directed mutational interrogation of the active site of the enzyme has identified Asp-375 to be the only residue uniquely and absolutely required for the enzyme’s epoxide hydrolase activity38. This therefore likely underlies the far superior capacity of compound 9 versus 2H-resveratrol to inhibit that capacity of LTA4H to generate LTB4. Overlaying our X-ray data of compound 9 bound within the active site of LTA4H with the published structure of OBP-Pro (4MS6.pdb) demonstrates that compound 9 occupies our target site A, without encroaching into the zinc binding arm (site B) that OBP-Pro, and by analogy PGP, occupies (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3. Compounds 9 and 15 make a hydrogen bond with Asp-375 within Site A of the active site of LTA4H.

(a) Green mesh surrounding Compound 9 (orange) shows the Fo-Fc difference map density (2σ level) having omitted the compound from the model. (b) Comparison of X-ray structure of 2H-resveratrol (blue; 3FTU.pdb) and compound 9 (bronze; our study) in Site A of LTA4H. The protein surface is coloured by amino acid hydrophobicity from most hydrophobic (orange) to hydrophilic (blue) through white regions. (c) Relative positions of 2H-resveratrol (blue) and compound 9 (bronze) showing hydrogen bonding interactions. 2H-resveratrol H-bonds to the carbonyl of Trp-311 and 3 water molecules (pink) and its position is further reinforced by a π-stacking interaction with the indole of Trp-311. Compound 9 adopts a head-to-tail orientation such that its hydroxyl groups form H-bonds to Asp-375, key for hydrolase activity, and a single water molecule (orange). (d) Compound 9 (pink) does not impinge significantly on the peptidase site delineated by OBP-Pro (white; 4MS6.pdb) when the X-ray structures of Compound 9-LTA4H (our study) and 4MS6.pdb are overlaid. Best scored poses of compound 12 (e; white) and compound 15 (f; orange) docked into site A of LTA4H with Autodock Vina. The R2 OH of compound 12 is located in a hydrophobic region so replacing this group with a methyl substituent (compound 15) improves interaction with the protein. In addition, a hydrogen-bonding interaction between the phenol of compound 15 and Asp-375 is also observed.

Thus compound 9 represented a chemical series with clear and rational potential to selectively inhibit the epoxide hydrolase activity of LTA4H. We next questioned whether this compound would exhibit a comparable capacity to inhibit LTB4 generation in human neutrophils. Preliminary data obtained using blood-derived neutrophils from two distinct donors demonstrated that compound 9 inhibited LTB4 generation with an IC50 of 2.4 μM – comparing favourably with that obtained with murine cells. Furthermore, it should be stressed that human neutrophils produced more LTB4 on a per cell basis than mouse neutrophils in our assays, and thus all compounds were slightly less potent in the human system. To determine whether compound 9 possessed suitable drug-like properties to merit advancement, in vitro ADMET studies were performed to assess plasma protein binding, microsome stability and logD (Supplementary Table S1). These studies highlighted that a potential weakness of compound 9 was that it was readily metabolized in microsomes and would thus be readily cleared in vivo.

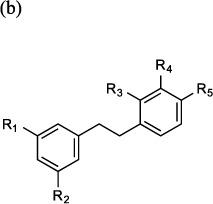

Isoflavone-based compounds to selectively target LTA4H

At this point it became clear that we needed to improve the drug-like properties of our series. Given the size restraints imposed by the binding site, our initial investigations focussed on identifying alternative groups to link the two aromatic rings. We found that amides lost all capacity to inhibit either activity but replacing the carbon adjacent to ring A with a ketone (compound 10) was tolerated showing preferential inhibition of the epoxide hydrolase activity (Table 3). Moreover, the isoflavone daidzein (compound 11), which incorporates the structure of compound 10, was equipotent with its uncyclized counterpart in terms of selective inhibition of the hydrolase activity (Table 3) and represents a new chemotype, with the additional benefit of greatly increased metabolic stability reported (t1/2 7.75 ± 0.36 h)39. A survey of commercially available isoflavones rapidly identified 7,8,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone (compound 12) with >8-fold selectivity for hydrolase over peptidase inhibition (Table 3). Docking compound 12 into the active site of LTA4H produces poses in which the new compound occupies the same region as resveratrol and in which the R3 hydroxyl makes a key interaction with the same hydrophilic patch of the enzyme (Fig. 3e); and the parallel behaviour of the two series supports this hypothesis. In sharp contrast to 9, we determined that the isoflavone compound 12 showed greatly increased metabolic stability over the resveratrol series in both mouse and human microsomes (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 3. Effect of isoflavones on inhibition (IC50) of the epoxide hydrolase (LTB4 generation) and aminopeptidase (PGP degradation) activities of LTA4H as described in Materials and methods.

| Cmpd. No. | R1 | R2 | R3 | Epoxide Hydrolase IC50 ± SEM (μM) | Aminopeptidase IC50 ± SEM (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| 10 | 34.24 ± 4.7 | >100 | |||

| 11 | OH | OH | H | 15.0 ± 2.3 | >100 |

| 12 | OH | OH | OH | 7.3 ± 0.8 | 62.7 ± 13.3 |

| 13 | H | OH | H | 48.2 ± 14.6 | >100 |

| 14 | OH | O-CH2-O | 20.6 ± 2.4 | 20.6 ± 3.3 | |

| 15 | OH | Me | OH | 1.2 ± 0.21 | 69.2 ± 10.9 |

IC50 curves were generated from 3 technical replicates at each concentration of test compound and at least 2 biological replicates. Results depicted as mean ± SEM.

Investigating the role of the hydroxyl substituents demonstrated that loss of the R1 and R3 hydroxyls from compound 12 (to give compound 13) diminished the capacity of the compound to inhibit the epoxide hydrolase activity of LTA4H, with docking studies suggesting that the R3 phenyl OH was no longer capable of finding the key binding interaction with a hydrophilic patch of the enzyme identified in the earlier structure-activity studies. Blocking both R3 and R2 hydroxyls by formation of the acetal (compound 14) also produced a modest reduction in hydrolase inhibition versus compound 12, whilst also increasing aminopeptidase inhibition (Table 3). However, replacing just the R2 hydroxyl of compound 12 with a methyl group (compound 15) gives a compound with increased ability to inhibit hydrolase activity, whilst showing clear selectivity versus aminopeptidase inhibition (Table 3). Docking studies rationalized this enhanced inhibition of epoxide hydrolase activity, with the R2 methyl making an additional interaction with a hydrophobic patch within the active site, whilst still allowing the R3 OH to hydrogen bond to the aforementioned hydrophilic region (Fig. 3f). Importantly, docking studies strongly suggest that the R1 OH of compound 15 is now able to make a hydrogen bond with Asp-375 (Fig. 3f), further rationalizing the potency and specificity with which it is able to inhibit the epoxide hydrolase activity of LTA4H. Thus compound 15 offered another chemical starting point for the development of selective LTA4H inhibitors but with greater metabolic stability.

Discussion

LTA4H inhibitors developed by pharmaceutical companies to alleviate LTB4-mediated pathologies have demonstrated clear target engagement, but failed to show efficacy in the clinic. In this study, we validated that clinically evaluated LTA4H inhibitors target both activities of the enzyme and importantly enable PGP accumulation in vivo, highlighting the necessity to generate selective compounds. Furthermore, we reveal that diphenyl ether derivatives purported to augment the aminopeptidase activity of LTA4H are ineffective when using the physiological substrate PGP. Finally, we identify two distinct chemical series that can selectively inhibit LTB4 generation whilst maintaining PGP degradation and may offer a starting point for the development of novel, superior and safer LTA4H modulators.

SC57461A, DG-051 and JNJ-40929837 have all been reported as potent, selective, orally efficacious inhibitors of LTB4 synthesis. However, we report for the first time that these compounds are equipotent at inhibiting PGP degradation, and rationalized this in terms of their encroachment into the peptide binding arm of the active site. We have previously reported the absolute requirement of LTA4H to degrade PGP in vivo utilizing knock out animals9,13. However, a valid caveat has been that LTA4H inhibitors may not yield comparable results to gene knock outs, with sufficient residual enzyme activity remaining to degrade PGP following inhibitor administration. It is telling therefore, that oral administration of SC57461A or JNJ-40929837 to naïve mice potently inhibited aminopeptidase activity and led to serum accumulation of PGP. PGP is anticipated to support persistent neutrophilic inflammation and ensuing pathology in chronic lung diseases such as COPD, CF and BOS where it inversely correlates with lung function, spikes with exacerbations and is reduced with in-patient therapy10,11,14,15,16,17. Furthermore, chronic administration of PGP alone into the lungs of mice is sufficient to elicit an emphysematous phenotype and neutralization of PGP can ameliorate cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary inflammation in mice11,40. Additionally, we have demonstrated that failure to degrade PGP in response to a relatively innocuous pulmonary bacterial challenge results in a more pronounced neutrophilic infiltrate, protease imbalance, ECM attack and enhanced illness and pathology – all hallmarks of aforementioned chronic lung disease characterized by persistent PGP13. Thus it is clearly apparent that perturbation of the LTA4H pathway in a manner that can facilitate PGP accumulation carries significant inherent risks. Accordingly, it is clear that we should be extremely vigilant to adverse effects of LTA4H inhibitors and novel selective drugs that can spare PGP degradation would be desirable.

More recent studies have reported the potential to pharmacologically manipulate the individual activities of LTA4H34,35,36. Indeed, 4-MDM has been reported to ameliorate disease in murine models of emphysema triggered by intranasal administration of elastase or long term cigarette smoke exposure by purportedly augmenting LTA4H aminopeptidase activity35,36. It is noteworthy however, that these studies have not assessed the capacity of 4-MDM to directly augment aminopeptidase activity of LTA4H against the physiological substrate PGP, instead using chromogenic amino acid analogues. In our hands, 4-MDM failed to augment PGP degradation, highlighting the importance of assaying enzyme activity using physiological, albeit more laborious, methodologies as opposed to those that enable high throughput screening. The success of 4-MDM in preclinical animal models, in light of these findings, is difficult to rationalize but could suggest an alternative peptide substrate for LTA4H or off target effects of 4-MDM given its likely low specificity and the substantial doses administered.

Recently, the Haeggstrom group elegantly demonstrated that the molecule ARM1 occupied the end of the L-shaped hydrophobic cavity, whilst still permitting a PGP analogue (OBP-Pro) to occupy the zinc binding site37. Accordingly, they showed that ARM1 could inhibit LTB4 generation by neutrophils with an IC50 of ~0.5 μM, whilst exhibiting no inhibition of PGP degradation at a concentration of 100 μM. In our experimental system, ARM1 exhibited a comparable capacity to inhibit LTB4 generation in cell based assays but also exhibited some capacity to inhibit PGP degradation - albeit still with marked selectivity towards inhibition of hydrolase activity. The discrepancy is almost certainly attributable to differing methodologies that are applied. When assessing aminopeptidase activity of LTA4H versus PGP we have utilized enzyme at a concentration of 0.1 μg/ml, in keeping with physiological levels of the enzyme found within the blood, whereas the Haeggstrom group have utilized 5 μg/ml LTA4H. Whilst the merits of subtle differences in experimental methodologies can be argued, the direct side-by-side interrogation of compounds in identical assays, as performed in our study, enabled us to confidently assess relative potencies and selectivity of these drugs. To our mind ARM1 was the only compound tested that exhibited a marked selectivity between enzyme activities and thus represented the gold standard to which our novel drugs should be compared.

Subsequently, we have developed two distinct chemical series that exhibit the capacity to inhibit LTA4H-mediated LTB4 generation whilst demonstrating exquisite selectivity and leaving the aminopeptidase activity largely unperturbed. Compound 9 exhibited sub-μM capacity to inhibit LTB4 generation in a cell based assay, whilst showing no inhibition of PGP degradation at 100 μM – thus exhibiting a superior selectivity to ARM1 in our hands. Rationalizing this selective inhibition, X-ray crystallography demonstrated that compound 9 formed a hydrogen bond with Asp-375. Previous site-directed mutagenesis studies have demonstrated that Asp-375 was absolutely required for hydrolysis of LTA4 into LTB4 but not for the peptidase activity – the only residue reported to be capable of making this distinction38. Whilst compound 9 exhibited a targeted potency and selectivity, preliminary studies suggest that it does not possess a suitable drug profile, being readily metabolized within microsomes. Thus whilst compound 9 represents a useful biological tool, further development would be mandatory to enhance in vivo stability. Subsequently, isoflavones were demonstrated to exhibit remarkable stability whilst still displaying a selective capacity to inhibit LTB4 generation. As a lead compound 15 was capable of inhibiting LTA4H epoxide hydrolase activity at the low μM range with minimal inhibition of aminopeptidase activity. This could again be rationalized in part by a predicted interaction with key epoxide hydrolase residue Asp-375. Thus compound 15 also represents an exciting candidate for further drug development. Within the isoflavone series, compound 12 contains a catechol that is recognized as a PAINS substructure. However, as this is the only example of such a feature within the isoflavone series, the capacity of this class of compounds to inhibit LTB4 generation is clearly specific. Nonetheless, it would be prudent to be vigilant to the presence of PAINS substructures in developing the isoflavone series towards the clinic.

Drug failures are common, multifactorial and often difficult to explain. In the case of LTA4H, however, the lack of clinical success could feasibly be attributable to the inadvertent inhibition of the enzyme’s anti-inflammatory aminopeptidase activity. Accordingly, the compounds identified within this study could act as starting points for the development of superior and safer LTA4H inhibitors to selectively target LTB4-mediated pathologies. However, whilst this study provides clear proof-of-concept for a rationalized selective LTA4H inhibitor, the compounds identified require significantly more optimization to generate inhibitors with a suitable drug profile that can be translated to the clinic. Clearly, there is a need to further assess the capacity of these compounds to inhibit LTB4 generation in a human cell based system, preferably with disease relevance. Furthermore, the studies detailed within this manuscript highlight the clear necessity to develop compounds with a superior ADMET/DMPK profile, and we have not as yet assessed selectivity of these compounds – pertinent given the mandatory small size of the drugs. If these issues can be overcome, however, there is a clear rationale to test these classes of selective LTA4H inhibitors in pre-clinical animal models and ultimately the clinic.

Methods

Compound procurement

Compound 1 (Resveratrol; 3,4′,5-Trihydroxy-trans-stilbene; 5-[(1E)-2-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)ethenyl]-1,3-benzenediol), compound 4 (Triacetyl resveratrol; (5-[(1E)-2-[4-(acetyloxy)phenyl]ethenyl]-1,3-Benzenediol-1,3-diacetate, 3,5,4′-Tri-O-acetylresveratrol), compound 5 (Pinostilbene hydrate; 3,4′-Dihydroxy-5-methoxy-trans-stilbene hydrate, 3-[(1E)-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethenyl]-5-methoxyphenol hydrate), compound 10 (1-(2,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethanone) and compound 12 (7,8,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone) were all purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Dorset, UK). Compound 2 (cis-Resveratrol) and compound 3 (trans-trismethoxy Resveratrol; (E)-5-[2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethenyl]-1,3-benzene diol) were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Michigan, USA). ARM1 (4-(4-benzylphenyl)-1,3-thiazole-2-amine), compound 11 (7-hydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one) and compound 13 (7-hydroxy-3-phenyl-4H-chromen-4-one) were all purchased from VitasMLab (Kowloon, Hong Kong). SC57461A was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK) and 4-Methoxydiphenylmethane (4-MDM) was purchased from Fluorochem, (Hadfield, UK). JNJ- 40929837 and DG-051 were synthesized by Peakdale Molecular (Derbyshire, UK) as previously described28,41. All other compounds were custom synthesized by Peakdale Molecular as described in Supplementary Information. ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion – toxicity) studies were also outsourced to Peakdale Molecular.

Molecular Modelling

Structures were analysed and visualized using UCSF Chimera (1.9–1.10) and docking experiments were run using this implementation of AutoDock Vina. The 1.25 Å resolution X-ray structure of human LTA4H in complex with SC57461 (3U9W.pdb) was prepared by running Dock Prep to add hydrogens, charges, and correct incomplete sidechains. Ligands were built in Chimera and prepared using the inbuilt ligand preparation script. AutoDock Vina was configured to generate 9 binding modes; the “Exhaustiveness of search” parameter was unchanged from the default of 8 and the maximum energy score range allowed for poses was set to 3 kcal/mol. A box 15 × 8 × 15 Å was set up to define the receptor search volume and the results analyzed with ViewDock.

Ligand-protein structures were compared by aligning the protein chains of the reference and match structure(s) using MatchMaker as implemented in Chimera. Chimera is developed by the Resource of Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (supported by NIGMS P41-GM103311).

Crystallography methods

LTA4H (Novoprotein, NJ, USA) at 6 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 25 mM KCl was crystallized at 18 °C by hanging drop vapour diffusion against a reservoir of 20% PEG 8000, 0.1 M Sodium Acetate, 0.15 mM Imidazole pH7.8, 5 mM YbCl3. Crystals were transferred to drops containing well solution supplemented with 20% (v/v) glycerol and saturating concentration (<10 mM) of compound 9 for 3 hrs, before being flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data were collected on beamline I02 at Diamond Light Source (Oxfordshire, UK), and processed with Mosflm and Scala of the ccp4 suite42,43,44. The structure was solved using pdb 5AEN as an initial model and refined using refmac and phenix iterated with manual model building using coot45,46,47 to give a final structure with an Rfree of 19.6% and good geometry (Supplementary Table S2). A stereo image showing electron density around compound 9 is depicted in Supplementary Figure S2. The coordinates and structure factors for LTA4H:Compound 9 have been deposited in the protein databank (PDB ID 5N3W).

Mouse procedures

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Use of Laboratory Animals of Imperial College London. All animal procedures and care conformed strictly to the UK Home Office Guidelines under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, and the protocols were approved by the Home Office of Great Britain. Six- to eight-week-old female BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan Olac Ltd (Oxon, UK). All mice were kept in specified-pathogen-free conditions and provided autoclaved food, water and bedding.

For murine ex vivo analysis of LTB4 production and PGP degradation, SC57461A (in physiological saline with 2% DMSO and 1% Tween 80), JNJ-40929837 (in 20% HPβCD) or relative vehicle controls were administered orally (10 mg/kg) to female BALB/c mice. Blood was obtained from mice 4 h after oral dosing and downstream analysis performed blinded by an independent researcher. To assess inhibition of epoxide hydrolase activity, blood (90 μl added to 10 μl 500 U/ml heparin) was diluted 1:1 in RPMI 1640 medium, after which 200 μl aliquots of the diluted blood were added to a microtiter plate. Calcium ionophore A-23187 (20 μg/ml final concentration) was added and the mixture incubated 20 min at 37 °C in a humidified incubator. The reaction was terminated by centrifugation (600 × g, 5 min, 4 °C). Supernatants were analyzed for LTB4 by EIA (see below). To assess inhibition of aminopeptidase activity, PGP degrading capacity of serum was assessed as detailed below. Furthermore, absolute concentrations of PGP in serum was determined as detailed below.

Cell isolation

To isolate murine bone marrow neutrophils, the femur and the tibia from both hind legs were removed and freed of soft tissue attachments, and the extreme distal tip of each extremity cut off. HBSS containing 15 mM EDTA and 30 mM HEPES was forced through the bone with a syringe. After dispersing cell clumps and passage through a 100 μM sieve (BD labware, New Jersey), red blood cells were lysed by resuspending pellets in ACK buffer (for 3 minutes at room temperature) before centrifugation (800 × g, 5 min) and washing with HBSS. The cell suspension was centrifuged (800 × g, 5 min, 4 °C) and resuspended in RPMI. The cells were layered onto a 72%, 64%, 52% Percoll gradient (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) diluted in PBS (100% Percoll = nine parts Percoll and one part 10x PBS), and centrifuged (1500 × g, 30 min, room temperature) without braking. The neutrophils at the 64%/72% interface were harvested and washed with 20 ml RPMI. Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion and confirmed to be >90% neutrophils by flow cytometry.

To isolate human neutrophils, peripheral blood was taken from healthy volunteers following informed consent and according to an approved protocol. Neutrophils were subsequently isolated using the MACSxpress™ Neutrophil Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, UK).

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were stained for surface markers in PBS containing 0.1% sodium azide and 1% BSA for 30 min at 4 °C and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. Data was acquired on a BD FACS Fortessa machine (BD Biosystems, UK). Forward scatter and side scatter gates were used to exclude debris and dead cells were excluded using a fixable near IR dead cell stain kit for 633 or 635 nm excitation. Neutrophils were defined as Ly-6Ghigh (Ly6G-FITC; BD Biosciences; clone 1A8), CD11bhigh (CD11b-PerCP; eBioscience; clone M1/70), CD11clow (CD11c-APC; BD Biosciences; clone HL3), F4/80low (F4/80-PE/Dazzle; BD Biosciences; clone BM8).

Liquid chromatography-electrospray-ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-LC/MS/MS) for PGP detection

For peptide quantification in serum, PGP and AcPGP were measured using a MDS Sciex API-4000 spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) equipped with a Shimadzu HPLC (Columbia, MD). For peptide quantification from degradation experiments, PGP and AcPGP were measured using a Thermo Accela Pump and Autosampler coupled to a Thermo TSQ Quantum Access. HPLC was done using a 2.0 × 150 mm Jupiter 4u Proteo column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) with A: 0.1% HCOOH and B: MeCN + 0.1% HCOOH: 0 min–0.5 min 5% buffer B/95% buffer A, then increased over 0.5–2.5 min to 100% buffer B/0% buffer A. Background was removed by flushing with 100% isopropanol/0.1% formic acid. Positive electrospray mass transitions were at 270–70, 270–116 and 270–173 for PGP and 312–140 and 312–112 of AcPGP. Peak area was measured, and PGP/AcPGP peptide concentrations were calculated using a relative standard curve method as previously described11.

Assessment of LTA4H aminopeptidase activity

Mouse serum (diluted 1/10 in PBS) or recombinant human LTA4H (0.1 μg/ml; Cayman Chemicals, Michigan, USA) were incubated with 0.4 mM PGP at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for varying periods of time. Concentrations of PGP remaining were subsequently quantified by ESI-LC/MS/MS (as discussed above) by comparison with PGP standards. The percentage of peptide degraded was determined relative to control samples of 0.4 mM PGP alone. PGP degradation was also assessed by measurement of free proline released and its ensuing reaction with Ninhydrin (as discussed below). Test compounds were assayed in a blinded manner by an investigator during determination of the effect on LTA4H aminopeptidase activity.

To assess free proline liberated, aliquots from PGP degradation experiments were diluted 1 in 10 in PBS (to a final volume of 250 μl). Glacial acetic acid (250 μl) was then added, followed by 250 μl of ninhydrin solution (25 mg/ml in acetic acid/6 M phosphoric acid; heated at 70 °C to dissolve). The reaction mixture was heated at 100 °C for 60 minutes, allowed to cool to room temperature and the proline containing fraction extracted with 500 μl of toluene and optical density measured at 520 nm.

Assessment LTA4H epoxide hydrolase activity

1 × 105 murine bone marrow-derived neutrophils or human blood-derived neutrophils (compound 9 only) in 100 μl of RPMI were treated with A23187 at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml. 1% DMSO was used as a control. Cells were incubated for 20 minutes at 37 °C, and the reaction was terminated by centrifugation (600 × g, 5 min, 4 °C). Supernatants were removed and stored at −80 °C for subsequent LTB4 analysis. The concentration of LTB4 generated in the epoxide hydrolase activity assay was assayed using an EIA, according to manufacturer’s directions (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN). Test compounds were assayed in a blinded manner by an investigator during determination of effect on LTA4H epoxide hydrolase activity.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Prism 4 (GraphPad Software Inc. La Jolla, CA, USA). Data was non-parametric and statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired Mann-Whitney test (two-tailed). All p-values of ≤0.05 (*) and ≤0.01 (**) were considered significant and are referred to as such in the text.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Low, C. M. et al. The development of novel LTA4H modulators to selectively target LTB4 generation. Sci. Rep. 7, 44449; doi: 10.1038/srep44449 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

R.J.S. is a Wellcome Trust Career Development Fellow (095707/Z/11/Z) and is also funded through an Asthma UK Innovations award (AUK-IG-2014-286). Aspects of this work have been funded (through R.J.S.) by the Imperial College Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) Therapeutic Primer fund and MRC/Imperial College Confidence in Concept schemes. C.M.L. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellow in Basic Biomedical Sciences (086718/Z/08/Z). S.H. is an MRC Career Development Fellow (G1100332). The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute funds J.E.B. (HL077783, HL110950, HL114439 and HL126596). The UAB Lung Health Center Pulmonary Proteomics Laboratory is funded through the UAB Health Service Foundation General Endowment Fund. We would like to thank Dr. Anna Caldwell and the Centre of Excellence for Mass Spectrometry at King’s College London for the use of equipment and technical assistance, and the staff of beamline I02 at Diamond Light Source for facilitating X-ray crystallography studies. We would like to thank Jen Morton, Matt Tozer, David Leese, Stuart Cameron, Seb Hallworth and David Fengas (all Peakdale Molecular) for compound synthesis and ADMET studies.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions C.L. and R.J.S. designed and interpreted the experiments and prepared the manuscript. R.J.S. with S.A., D.F.P. and S.L. performed the majority of the experiments. S.H. performed and analysed the X-ray crystallography with the assistance of C.W., P.L.J. aided with mass spectrometry, and P.L.J., J.E.B. and C.M.L. contributed discussions throughout the work.

References

- Haeggstrom J. Z., Tholander F. & Wetterholm A. Structure and catalytic mechanisms of leukotriene A4 hydrolase. Prostaglandins & other lipid mediators 83, 198–202 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk C. D. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science 294, 1871–1875 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tager A. M. & Luster A. D. BLT1 and BLT2: the leukotriene B(4) receptors. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and essential fatty acids 69, 123–134 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Gennaro A. & Haeggstrom J. Z. The leukotrienes: immune-modulating lipid mediators of disease. Advances in immunology 116, 51–92 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle B. J. et al. Attenuation of inflammation and cytokine production in rat colitis by a novel selective inhibitor of leukotriene A4 hydrolase. British journal of pharmacology 153, 983–991 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths R. J. et al. Leukotriene B4 plays a critical role in the progression of collagen-induced arthritis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 92, 517–521 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailie M. B. et al. Leukotriene-deficient mice manifest enhanced lethality from Klebsiella pneumonia in association with decreased alveolar macrophage phagocytic and bactericidal activities. Journal of immunology 157, 5221–5224 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. S., Sheller J. R., Johnson E. N. & Funk C. D. Role of leukotrienes revealed by targeted disruption of the 5-lipoxygenase gene. Nature 372, 179–182, doi: 10.1038/372179a0 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snelgrove R. J. et al. A critical role for LTA4H in limiting chronic pulmonary neutrophilic inflammation. Science 330, 90–94 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaggar A. et al. A novel proteolytic cascade generates an extracellular matrix-derived chemoattractant in chronic neutrophilic inflammation. Journal of immunology 180, 5662–5669 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathington N. M. et al. A novel peptide CXCR ligand derived from extracellular matrix degradation during airway inflammation. Nature medicine 12, 317–323 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. et al. A self-propagating matrix metalloprotease-9 (MMP-9) dependent cycle of chronic neutrophilic inflammation. PloS one 6, e15781 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akthar S. et al. Matrikines are key regulators in modulating the amplitude of lung inflammation in acute pulmonary infection. Nature communications 6, 8423 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly P. et al. N-alpha-PGP and PGP, potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for COPD. Respiratory research 10, 38 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J. M. et al. An aberrant leukotriene A4 hydrolase-proline-glycine-proline pathway in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 190, 51–61 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J. M. et al. A Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial of Roflumilast. Effect on Proline-Glycine-Proline and Neutrophilic Inflammation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 192, 934–942, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardison M. T. et al. The presence of a matrix-derived neutrophil chemoattractant in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation. Journal of immunology 182, 4423–4431 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snelgrove R. & Kheradmand F. Leukotriene A4 hydrolase: the Janus enzyme shows its ugly side in smokers. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 190, 5–7 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snelgrove R. J. Leukotriene A4 hydrolase: an anti-inflammatory role for a proinflammatory enzyme. Thorax 66, 550–551 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thunnissen M. M., Nordlund P. & Haeggstrom J. Z. Crystal structure of human leukotriene A(4) hydrolase, a bifunctional enzyme in inflammation. Nature structural biology 8, 131–135 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeggstrom J. Z. Structure, function, and regulation of leukotriene A4 hydrolase. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 161, S25–31 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeggstrom J. Z. Leukotriene A4 hydrolase/aminopeptidase, the gatekeeper of chemotactic leukotriene B4 biosynthesis. The Journal of biological chemistry 279, 50639–50642 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourie A. M. Modulation of inflammatory disease by inhibitors of leukotriene A4 hydrolase. Current opinion in investigational drugs 10, 1173–1182 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barchuk W. et al. Effects of JNJ-40929837, a leukotriene A4 hydrolase inhibitor, in a bronchial allergen challenge model of asthma. Pulmonary pharmacology & therapeutics 29, 15–23 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachur J. F. et al. Pharmacological characterization of SC-57461A (3-[methyl[3-[4-(phenylmethyl)phenoxy]propyl]amino]propanoic acid HCl), a potent and selective inhibitor of leukotriene A(4) hydrolase II: in vivo studies. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 300, 583–587 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askonas L. J. et al. Pharmacological characterization of SC-57461A (3-[methyl[3-[4-(phenylmethyl)phenoxy]propyl]amino]propanoic acid HCl), a potent and selective inhibitor of leukotriene A(4) hydrolase I: in vitro studies. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 300, 577–582 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caliskan B. & Banoglu E. Overview of recent drug discovery approaches for new generation leukotriene A4 hydrolase inhibitors. Expert opinion on drug discovery 8, 49–63 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies D. R. et al. Discovery of leukotriene A4 hydrolase inhibitors using metabolomics biased fragment crystallography. Journal of medicinal chemistry 52, 4694–4715 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enache L. A. et al. Synthesis and structural assignment of two major metabolites of the LTA4H inhibitor DG-051. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 19, 6275–6279 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandanayaka V. et al. Discovery of 4-[(2S)-2-{[4-(4-chlorophenoxy)phenoxy]methyl}-1-pyrrolidinyl]butanoic acid (DG-051) as a novel leukotriene A4 hydrolase inhibitor of leukotriene B4 biosynthesis. Journal of medicinal chemistry 53, 573–585 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao N. L. et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of a potent, selective leukotriene A4 hydrolase inhibitor in comparison with the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor zileuton. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 321, 1154–1160 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grice C. A. et al. Identification of a potent, selective, and orally active leukotriene a4 hydrolase inhibitor with anti-inflammatory activity. Journal of medicinal chemistry 51, 4150–4169 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao N. L. et al. Leukotriene A(4) hydrolase inhibition attenuates allergic airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 181, 899–907 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X. et al. Activation and inhibition of leukotriene A4 hydrolase aminopeptidase activity by diphenyl ether and derivatives. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 18, 6549–6552 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira E. O. et al. Effect of the leukotriene A4 hydrolase aminopeptidase augmentor 4-methoxydiphenylmethane in a pre-clinical model of pulmonary emphysema. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 21, 6746–6750 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paige M. et al. Role of leukotriene A4 hydrolase aminopeptidase in the pathogenesis of emphysema. Journal of immunology 192, 5059–5068 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stsiapanava A. et al. Binding of Pro-Gly-Pro at the active site of leukotriene A4 hydrolase/aminopeptidase and development of an epoxide hydrolase selective inhibitor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111, 4227–4232 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudberg P. C., Tholander F., Thunnissen M. M., Samuelsson B. & Haeggstrom J. Z. Leukotriene A4 hydrolase: selective abrogation of leukotriene B4 formation by mutation of aspartic acid 375. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99, 4215–4220 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell K. D. et al. Comparing the pharmacokinetics of daidzein and genistein with the use of 13C-labeled tracers in premenopausal women. The American journal of clinical nutrition 77, 411–419 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braber S. et al. Cigarette smoke-induced lung emphysema in mice is associated with prolyl endopeptidase, an enzyme involved in collagen breakdown. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology 300, L255–265 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patent Number 2009126806.

- Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 62, 72–82 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn M. D. et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 67, 235–242 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie A. G. W. & Powell H. R.. Processing Diffraction Data with Mosflm. Evolving Methods for Macromolecular Crystallography. 245, 41–51 ISBN 978-1-4020-6314-5 (2007).

- Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A. & Dodson E. J. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 53, 240–255 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G. & Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.